Tax Insight: For Tax Year 2014 and Beyond, 3rd ed. Edition (2015)

Part II. Ordinary Income

Chapter 7. Retirement Income

Even During the Golden Years the IRS Is Still After Your Gold

People find numerous ways to pay for their expenses in retirement. Some live off of savings. Some have pensions. Many depend on Social Security, and others work “till they drop,” so to speak. For most people, the strategy is to use a combination of these.

Because of the great variety of income sources in retirement, nearly every form of taxation comes into play in retirement tax planning. There is the taxation for ordinary income, tax-exempt income, preferred income, deferred income, potentially and partially taxed income, etc. Each of these income sources, as you know, comes with its own set of rules that govern how it is taxed.

Many of these sources of income are covered in other chapters of this book. However, there are three common types of retirement income that have unique rules attached to them, which are the focus of this chapter. These unique rules create the need for special tax planning and awareness. The three income sources that are governed by these special rules are:

· Social Security income

· Pensions and annuities

· Retirement accounts and Required Minimum Distributions

It is critical to understand these rules as you plan for your retirement, so that you can be aware of the significant effect that taxes can have on your income during those “golden” years.

Social Security Income

Once you begin receiving Social Security benefits you will need to pay close attention to a new wrinkle this creates in your tax formula. When your total income exceeds a threshold, the income you receive from Social Security begins to be taxed. As your income increases over that threshold, the amount of Social Security income that is taxed also increases until a maximum of 85% of your Social Security income is taxed. The way that the formula is set up actually creates a multiplying effect on your tax, meaning your total tax will increase more rapidly than your marginal tax rates would suggest.

The formula that calculates the amount of Social Security income subject to tax creates some important tax planning issues. The good news is that by understanding the formula for Social Security taxation you will be able to structure your income properly to avoid as much of this additional taxation as possible.

If the income that you receive from Social Security were sufficient to maintain a desirable lifestyle, this additional tax would likely not be a concern. In nearly all cases, the government taxes Social Security income only if you are also drawing income from other sources. However, for many people, the paltry amount of income that Social Security provides is just not enough. For this reason, many choose to supplement their Social Security through other sources, be it drawing money from their savings and retirement accounts or finding employment. Even those who do not need extra income can be affected as they are forced to withdraw money from their retirement accounts when they are older than 70½ and the tax code requires minimum distributions. Whatever the case may be, if you have sources of income that are in addition to your Social Security income, you must pay special attention to the tax consequences that come from that additional income.

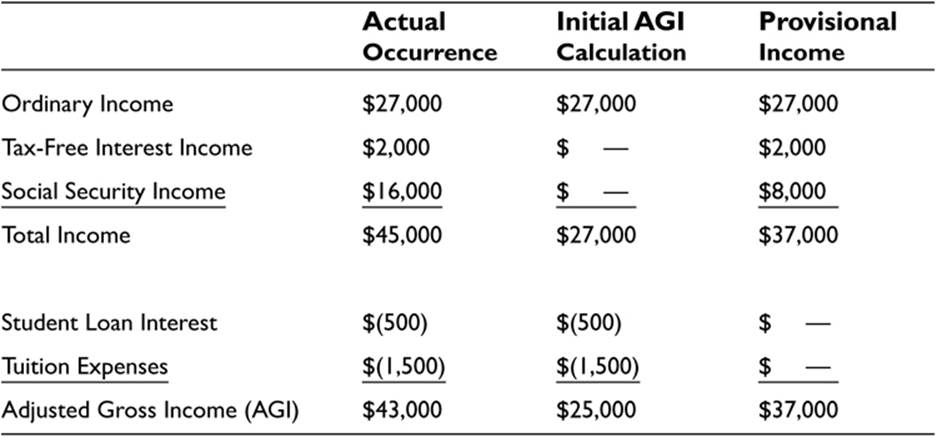

The taxation of Social Security income occurs in a stair-step fashion through a fairly complicated formula. The first step in the formula is calculating something called “provisional income.” Knowing how provisional income is calculated is the key to understanding how to plan for and manage this tax. Provisional income is determined by adding tax-free interest income, deductions taken for student loan interest, deductions taken for tuition expenses, and one half of your Social Security income to your Adjusted Gross Income (AGI), as seen in Table 7-1.

Table 7-1. Provisional Income Calculation

Provisional income is calculated by adding four additional numbers into the initial calculation for AGI.

If your provisional income is above the applicable threshold, the next part of the formula kicks in and a portion of your Social Security income becomes subject to tax. The first threshold that triggers taxation is when provisional income reaches $32,000 for those who are married and filing jointly (MFJ), or $25,000 for all other taxpayers. (There are special rules for those who file separately [MFS] but lived together during the year.) If your provisional income is above the threshold, then every dollar of provisional income over that threshold results in $0.50 of Social Security income becoming subjected to tax.

![]() Example Assume that Table 7-1 represents the income and deductions of Mitch and Liz. Their provisional income calculation came to $32,000. This means that their provisional income is above the first threshold ($37,000 provisional income – $32,000 threshold = $5,000). Because they are $5,000 over the threshold, $2,500 of their Social Security income will be subject to taxes and will be an increase to their final AGI.

Example Assume that Table 7-1 represents the income and deductions of Mitch and Liz. Their provisional income calculation came to $32,000. This means that their provisional income is above the first threshold ($37,000 provisional income – $32,000 threshold = $5,000). Because they are $5,000 over the threshold, $2,500 of their Social Security income will be subject to taxes and will be an increase to their final AGI.

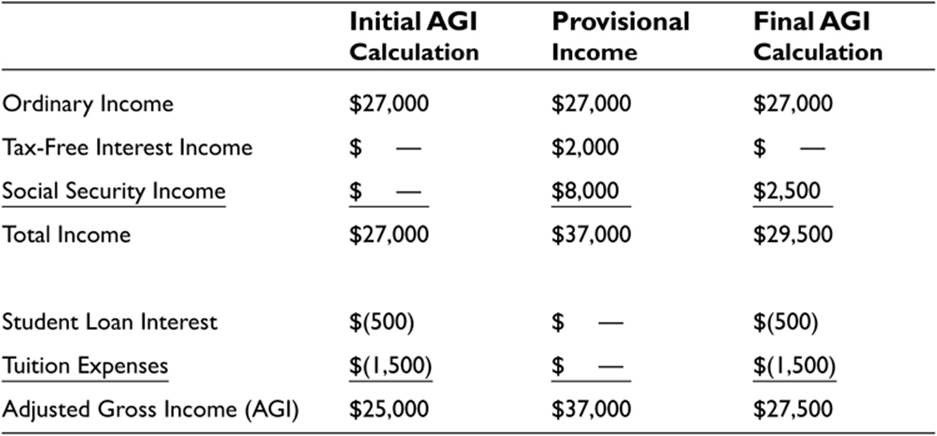

Table 7-2 illustrates how the inclusion of Social Security income occurs, as described in the previous example.

Table 7-2. Social Security Income Subjected to Taxation Calculation

Because the provisional income is $5,000 above the initial threshold, $2,500 of the Social Security income (or one half of the amount over the threshold) becomes a part of AGI and is taxed.

There is also a second threshold in this stair-step formula. When provisional income reaches $44,000 (MFJ) or $34,000 (all others), every dollar of income above the second threshold causes $0.85 of Social Security income to be taxed (instead of $0.50), until a full 85% of your Social Security is included in taxable income. No more than 85% of Social Security income can be taxed.

![]() Example If the numbers in Tables 7-1 and 7-2 were actually for Mitch as a single taxpayer (no longer Mitch and Liz), the provisional income would be above both thresholds. The first threshold for a single tax payer is $25,000 and the second is $34,000. So, the $9,000 of provisional income between the first and second thresholds would have caused $4,500 of his Social Security income to be taxed (one half of the amount over the initial threshold), and the $3,000 of provisional income over the second threshold would have caused an additional $2,550 to be taxed (85% of the amount over the second threshold). Those two amounts combined would make a total of $7,050 of Mitch’s Social Security income subject to tax, or 88.1% of the $8,000. However, no more than 85% of all Social Security income can be taxed, so the total amount of his Social Security income subject to tax would be reduced to $6,800 (85% max × $8,000 S.S income = $6,800), which is the actual amount that would be added into his AGI.

Example If the numbers in Tables 7-1 and 7-2 were actually for Mitch as a single taxpayer (no longer Mitch and Liz), the provisional income would be above both thresholds. The first threshold for a single tax payer is $25,000 and the second is $34,000. So, the $9,000 of provisional income between the first and second thresholds would have caused $4,500 of his Social Security income to be taxed (one half of the amount over the initial threshold), and the $3,000 of provisional income over the second threshold would have caused an additional $2,550 to be taxed (85% of the amount over the second threshold). Those two amounts combined would make a total of $7,050 of Mitch’s Social Security income subject to tax, or 88.1% of the $8,000. However, no more than 85% of all Social Security income can be taxed, so the total amount of his Social Security income subject to tax would be reduced to $6,800 (85% max × $8,000 S.S income = $6,800), which is the actual amount that would be added into his AGI.

The most sinister part of this taxation formula is that once your income goes above the provisional-income threshold, each additional dollar you earn is essentially taxed twice. If, for example, you earn an extra dollar at work or in your savings, you will obviously pay income taxes on it. However, in addition to those taxes you will also pay income tax on $0.50 to $0.85 of Social Security income that you wouldn’t have paid tax on before you earned that dollar.

![]() Example Bill and Emily have a joint income of $48,000, placing them in the 15% tax bracket. Normally this marginal tax bracket would mean that each additional dollar of income that they earn would be taxed at 15%. However, because they are Social Security recipients, each additional dollar that Bill or Emily earns will effectively be taxed at a rate of 27.75%—almost twice as much—because each additional dollar of income also causes $0.85 of Social Security income to be newly taxed.

Example Bill and Emily have a joint income of $48,000, placing them in the 15% tax bracket. Normally this marginal tax bracket would mean that each additional dollar of income that they earn would be taxed at 15%. However, because they are Social Security recipients, each additional dollar that Bill or Emily earns will effectively be taxed at a rate of 27.75%—almost twice as much—because each additional dollar of income also causes $0.85 of Social Security income to be newly taxed.

Knowing your provisional income allows you to make educated decisions about earning additional income. Understanding how this complicated formula works will help you be aware of the amount of additional gross income you need, in order to arrive at the true post-tax income that will be available to you for your retirement needs.

![]() Tip Once a full 85% of your Social Security income is being taxed the issue is off of the table. At that point it is no longer necessary to calculate the effects that additional income will have on the taxation of your Social Security. For example, a single individual with a $70,000 AGI has already been taxed to the maximum amount on his Social Security income. Any additional income will be taxed only at the applicable rates for that new income. For this reason, you need to consider the taxation of Social Security income only if you are within (or close to) the range of provisional income where there are incremental, disproportionate effects on your tax.

Tip Once a full 85% of your Social Security income is being taxed the issue is off of the table. At that point it is no longer necessary to calculate the effects that additional income will have on the taxation of your Social Security. For example, a single individual with a $70,000 AGI has already been taxed to the maximum amount on his Social Security income. Any additional income will be taxed only at the applicable rates for that new income. For this reason, you need to consider the taxation of Social Security income only if you are within (or close to) the range of provisional income where there are incremental, disproportionate effects on your tax.

Understanding the formulas that affect the taxation of Social Security income is important not only to those who currently receive Social Security benefits. Before reaching retirement you should carefully consider the effects of this tax on your retirement income as you make plans for the amount and sources of income that you will need to meet your needs.

![]() Caution Be aware that if you are in the range of provisional income where more Social Security dollars are being taxed with each additional dollar earned, the effectiveness of many tax reduction strategies (such as income from tax-exempt interest, qualified dividends, and long-term capital gains) is diminished. Because a dollar from any income source causes an additional dollar from Social Security to be taxed, even “tax-free” income is essentially being taxed.

Caution Be aware that if you are in the range of provisional income where more Social Security dollars are being taxed with each additional dollar earned, the effectiveness of many tax reduction strategies (such as income from tax-exempt interest, qualified dividends, and long-term capital gains) is diminished. Because a dollar from any income source causes an additional dollar from Social Security to be taxed, even “tax-free” income is essentially being taxed.

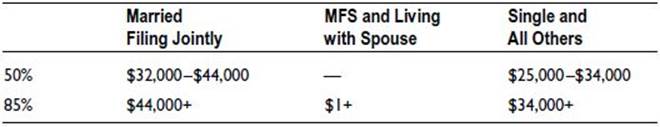

Table 7-3 summarizes the levels of provisional income that trigger taxation of Social Security income and the amount of that income that can be taxed at those thresholds.

Table 7-3. Social Security Taxation Provisional Income Thresholds and Amounts Taxed

Pensions and Annuities

Pensions and annuities are essentially the same thing. Both provide a pre-determined income stream to an individual for a set amount of time. The duration of the income stream can be for a fixed number of years or it can be for the life of the recipient, no matter how long he or she lives. (In some cases it continues for the life of the individual and his or her spouse.) The main difference between a pension and an annuity is that a pension is generally provided by an employer and an annuity is usually set up by an individual on his own.

The income stream from a pension or an annuity is partially taxable. The portion of that income that represents investments the individual made is tax-free. Many employers require employees to contribute to the pension from their paychecks. As this portion of the money comes back during the pension’s payout years, it is free from tax and considered a return of principal, not income. The same is the case for all of the money contributed by an individual to an annuity.

The portion that represents the growth of the account, or the payments made by the employer, is taxable to the individual at ordinary income tax rates. Note that even the growth of the account is taxed at ordinary rates, not at capital gains rates as would normally be the case for investment gains. Although a benefit of an annuity is the deferral of tax during growth years, the higher taxation of that growth at ordinary rates may lessen the benefits of the deferral.

The amount of income that is considered tax-free vs. taxable is determined by the expected duration of the income. For example, if an annuity is fixed as an income stream for 10 years, no matter how long the individual lives, and the total investment made into the annuity was $50,000, then $5,000 per year will be considered a tax-free return of investment and any amounts of income from the annuity that are greater than $5,000 during the year will be considered taxable income ($50,000 total investment/10 years = $5,000 per year return of principal).

If an annuity or pension will be paid over a person’s lifetime, instead of a fixed number of years, then IRS life expectancy tables are used to estimate the duration of the payments.

![]() Example Sarah is 62 years old and has just retired. She has begun receiving income from her annuity and has chosen to receive the payments for the length of her life, not for any fixed number of years. The annuity income will be $1,000 per month ($12,000 per year). If the IRS tables placed her expected years of life at 25 years, then the total expected payments from the annuity would be $300,000 ($12,000 per year × 25 years = $300,000). Sarah’s total investment in the annuity was $120,000. Based on this information, 40% of Sarah’s annuity income would be considered a tax-free return of principal ($120,000 total investment/$300,000 total expected income = 40%). From Sarah’s total annuity income of $12,000, $7,200 would be taxable and $4,800 would be tax-free (40% tax free × $12,000 = $4,800).

Example Sarah is 62 years old and has just retired. She has begun receiving income from her annuity and has chosen to receive the payments for the length of her life, not for any fixed number of years. The annuity income will be $1,000 per month ($12,000 per year). If the IRS tables placed her expected years of life at 25 years, then the total expected payments from the annuity would be $300,000 ($12,000 per year × 25 years = $300,000). Sarah’s total investment in the annuity was $120,000. Based on this information, 40% of Sarah’s annuity income would be considered a tax-free return of principal ($120,000 total investment/$300,000 total expected income = 40%). From Sarah’s total annuity income of $12,000, $7,200 would be taxable and $4,800 would be tax-free (40% tax free × $12,000 = $4,800).

If a person lives longer than the IRS’s expected lifetime, then all of the annuity income received after that point would be taxable, since the entire invested principal had been previously accounted for in tax-free income. It is important to understand how the taxation of pensions and annuities works so that you are able to plan properly for the after-tax income you will need in retirement.

Retirement Accounts (the Non-Roth Variety) and Required Minimum Distributions

Most people have at least a little money in a government-regulated (qualified) retirement plan by the time they retire. These plans feature tax deductibility when putting money in (most of them) and tax deferral while the money remains in the account (meaning that the growth of the investments is not taxed as long as it remains in the account). There are numerous versions of these plans, but some of the most common types of these retirement accounts are:

· 401(k) plans

· 403(b) plans

· 457 (b) plans

· Individual Retirement Account (IRA)

· Simplified Employee Pension (SEP) IRA plans

· Salary Reduction Simplified Employee Pension) (SARSEP) plans

· Savings Incentive Match Plan for Employees (SIMPLE) IRA plans

· Profit-sharing plans

When you remove money from a qualified retirement account it is generally taxed at ordinary income rates. This is the case even if some of the funds in the account have come from the growth of the investments (which would normally be taxed at the lower capital gains rates). This fact is a significant downside to using such accounts, which must be weighed against the benefits of the account before investing in one.

Because of the tax consequences of withdrawing funds from qualified accounts, many people prefer to leave the funds in the account for as long as possible to allow them to continue to grow with tax deferral. However, the government wants to ensure that it gets its money at some point (none of the money in the account has ever been taxed), so the tax code requires that an individual begin taking a minimum amount out of the account each year once he or she is 70½ years old. This mandatory withdrawal (and taxation) of the account’s funds is called a Required Minimum Distribution (RMD).

![]() Note If an individual is still employed when he or she is 70½, the requirement to withdraw money from an employer-sponsored plan is postponed until the person retires. However, this is not the case for IRAs or for employer plans where the individual is a 5% or more owner in the business; in these two cases the RMDs must be taken even if the individual is still employed.

Note If an individual is still employed when he or she is 70½, the requirement to withdraw money from an employer-sponsored plan is postponed until the person retires. However, this is not the case for IRAs or for employer plans where the individual is a 5% or more owner in the business; in these two cases the RMDs must be taken even if the individual is still employed.

![]() Caution While it may seem tempting to just ignore this rule and not take any distributions, do not give into that temptation. Congress anticipated that many would be so inclined and has imposed one of the stiffest penalties in the entire tax code failing to take an RMD. The IRS requires investment companies to report to them the value of your qualified accounts each year and if you do not take an RMD sufficient to cover the minimum requirement you will be fined 50% of the amount that you should have taken!

Caution While it may seem tempting to just ignore this rule and not take any distributions, do not give into that temptation. Congress anticipated that many would be so inclined and has imposed one of the stiffest penalties in the entire tax code failing to take an RMD. The IRS requires investment companies to report to them the value of your qualified accounts each year and if you do not take an RMD sufficient to cover the minimum requirement you will be fined 50% of the amount that you should have taken!

![]() Tip A request for waiver of this penalty can be made on Form 5329 (with a letter of explanation attached) if it can be shown that the shortfall was due to a reasonable error and that reasonable steps are being taken to remedy the shortfall. Just know that “I forgot” probably won’t qualify as reasonable if it is the sole reason given.

Tip A request for waiver of this penalty can be made on Form 5329 (with a letter of explanation attached) if it can be shown that the shortfall was due to a reasonable error and that reasonable steps are being taken to remedy the shortfall. Just know that “I forgot” probably won’t qualify as reasonable if it is the sole reason given.

There are a set of formulas and tables that determine the amount that you must take out each year. In essence, the formulas and tables seek to estimate your anticipated lifespan and divide up the account over that lifespan so that the last dollar will be withdrawn in the last year of your expected life. Each year your expected lifespan is recalculated based on your current age, and the amount that you are required to take out of the account changes accordingly. The amount that you are required to withdraw is a predetermined percentage of the value of each of your qualified accounts on the last day of the previous year.

![]() Example Karen will be 75 years old on the last day of the current year. On the last day of the previous year the value of Karen’s qualified account was $100,000. According to the IRS tables, at age 75 Karen must withdraw at least 4.367% of that year-end value from her qualified account during the current year, or $4,367. (Actually, the IRS guidelines instruct Karen to divide the account balance by her expected life span [found in the tables], which at age 75 is 22.9 years. This works out to be the same number as shown in the calculation above, only presented in a different way.)

Example Karen will be 75 years old on the last day of the current year. On the last day of the previous year the value of Karen’s qualified account was $100,000. According to the IRS tables, at age 75 Karen must withdraw at least 4.367% of that year-end value from her qualified account during the current year, or $4,367. (Actually, the IRS guidelines instruct Karen to divide the account balance by her expected life span [found in the tables], which at age 75 is 22.9 years. This works out to be the same number as shown in the calculation above, only presented in a different way.)

For the year that a taxpayer turns 70½ the withdrawal must be made no later than April 1 of the following year. For all subsequent years the RMD must be taken no later than December 31 of the current year. Withdrawing the amount later than the deadline will result in the 50% penalty mentioned previously. The three IRS tables that govern RMD distributions (showing the distribution factors based on the person’s age) are reproduced in the Appendix of this book, and can also be found in the IRS Publication 590, as well as on the IRS website.

The calculation to determine the RMD must be made separately for each qualified account that the individual owns. However, once the calculation is made, the full RMD for all IRA accounts may be taken from one IRA, as is also the case with 403(b) accounts. This is not the case, though, with other types of qualified accounts, such as 401(k)s and 457(b)s. These types of accounts require a separate distribution from each account.

![]() Note This chapter focuses only on the issues related to withdrawals from non-Roth qualified accounts. For a discussion on the benefits of contributing to a retirement account, see the retirement strategies chapters found in Part 3 of this book.

Note This chapter focuses only on the issues related to withdrawals from non-Roth qualified accounts. For a discussion on the benefits of contributing to a retirement account, see the retirement strategies chapters found in Part 3 of this book.

Are there any ways to reduce this tax burden?

In recent years there has been one way available to avoid the tax effects of an RMD. In the past Congress had allowed the direct transfer of an RMD to charitable organizations. (It doesn’t work to take the money out and then give it to charity—it must be a direct transfer.)

Making a direct charitable contribution of your RMD could have several benefits. This is because such a transfer keeps the RMD from becoming a part of your AGI. The subsequent reduction in AGI can have a positive effect on the amount of Social Security income that is taxed, help you avoid the Medicare surcharge that was enacted as part of the Affordable Care Act, and possibly keep your AGI below key phase-outs of deductions and credits. None of these benefits is available using the normal itemized deduction for charitable contributions, which only reduces your taxable income (and that is only if all of your itemized deductions add up to more than the standard deduction).

![]() Note As of the publication deadline of this book, this tax break expired at the end of 2013. However, reauthorization of this provision has historically been done near the end of the year, and is widely expected to happen retroactively for 2014 after the elections. Be sure to check if it is available for 2014 and beyond.

Note As of the publication deadline of this book, this tax break expired at the end of 2013. However, reauthorization of this provision has historically been done near the end of the year, and is widely expected to happen retroactively for 2014 after the elections. Be sure to check if it is available for 2014 and beyond.

How do RMDs affect an individual who receives an IRA through an inheritance (a beneficiary IRA)?

There are three ways that an inherited IRA is dealt with, based on the relationship of the beneficiary to the deceased person and whether the deceased person had reached the age for RMDs prior to his or her death.

First, if the person inheriting the IRA is the spouse of the deceased individual, the beneficiary can choose to treat the IRA as his or her own by rolling it into another IRA or just changing the name on the account. By doing so, the IRA RMD calculations would be based on thebeneficiary’s age, not the age of the deceased. Alternatively, the spouse may elect to treat the IRA as any another beneficiary would.

For a beneficiary who is not a spouse (or a spouse who chooses this route) there are three possibilities. First, the beneficiary may withdraw the entire IRA and pay taxes on the withdrawal accordingly. Second, if the original owner had not reached 70½ by the time of death, the beneficiary will base the IRA distributions on his or her own age. Third, if the original owner was older than 70½ at the time of death, the beneficiary can take RMDs based on the longer of his or her own life expectancy, or the life expectancy (from the tables) of the deceased (had there been no death).

![]() Caution If the deceased IRA owner would have been required to take an RMD, that RMD must be taken in his or her behalf and sent to the estate before the IRA is transferred into the name of the beneficiary.

Caution If the deceased IRA owner would have been required to take an RMD, that RMD must be taken in his or her behalf and sent to the estate before the IRA is transferred into the name of the beneficiary.

![]() Note There are other rules governing the distributions of IRAs for beneficiaries, such as what to do if the beneficiary is not an individual (such as a trust), or there are multiple beneficiaries, or the beneficiary dies and there is another beneficiary, etc. These issues are beyond the intended scope of this book and should be discussed with a competent tax professional.

Note There are other rules governing the distributions of IRAs for beneficiaries, such as what to do if the beneficiary is not an individual (such as a trust), or there are multiple beneficiaries, or the beneficiary dies and there is another beneficiary, etc. These issues are beyond the intended scope of this book and should be discussed with a competent tax professional.