Switching to the Mac: The Missing Manual, Mavericks Edition (2014)

Part II. Making the Move

Chapter 6. Transferring Your Files to the Mac

A huge percentage of “switchers” do not, in fact, switch. Often, they just add. They may get a Macintosh (and get into the Macintosh), but they keep the old Windows PC around, at least for a while. If you’re in that category, get psyched. It turns out that communicating with a Windows PC is one of the Mac’s most polished talents.

That’s especially good news in the early days of your Mac experience. You probably have a good deal of stuff on the Windows machine that you’d like to bring over to the Mac. Somewhere along the line, somebody probably told you how easy this is to do. In fact, the Mac’s reputation for simplicity may even have played a part in your decision to switch.

In any case, this chapter describes the process of building a bridge from the PC to the Mac, so that you can bring all your files and settings into their new home. It also tells you where to put them all.

As it turns out, files can take one of several roads from your old PC to your new Mac. For example, you can transfer them on a disk (such as a CD or iPod), by a network, or as an attachment to an email message.

TIP

The first part of this chapter covers the mechanical aspects of moving files and folders from your Windows PC to the Mac. On Transfers by Dropbox, you’ll find a more pointed discussion of where to put each kind of data (mail, photos, music, and so on) once it’s on the Mac.

Transfers by Apple Genius

By far the easiest way to transfer all the stuff from your PC to your new Mac is to let Apple do it for you. Yes, that’s right: Those busy Geniuses who work at the 400 Apple Stores around the world are prepared to bring your music, pictures, documents, address book, email, bookmarks, and other things to their new home on your Mac.

This service is included in the $100 One on One program, which is worth a look. (You’re supposed to buy One on One at the time you buy the Mac.)

One on One gives you a year’s worth of weekly one-hour private lessons at an Apple Store from an Apple rep. They’ll teach you the Mac, help you organize your photos, teach you the software, whatever you need. That’s gotta be the best private-lessons price ever offered for anything.

Once you’re signed up, the Apple Genius will take your old PC and your new Mac and do the transferring for you. For example, all your Windows pictures (even if they’re in Picasa or special photo-editing programs from HP or Kodak) get brought over to the Mac and imported into iPhoto. All your music is imported into iTunes on the Mac. Your documents and movies get copied to the Documents and Movies folders on the Mac. Your Web bookmarks from Internet Explorer or Firefox get transferred to Safari on the Mac. Even your email, address book, and calendar get transferred from Outlook or Outlook Express on the PC and brought into Mail, Contacts, and Calendar on the Mac.

The rest of this chapter covers do-it-yourself ways to transfer your stuff. But, man, there’s nothing like having a professional do it for you.

The Windows Migration Assistant

If you don’t really need the year’s worth of private Mac lessons, then here’s another low-effort option: Let the Windows Migration Assistant do the transferring for you.

Now, this app has a reputation for bugginess. But if it works on your system, it’s a nearly effortless automatic tool that copies all your important data from a Windows PC (running Windows XP SP3 or later) to your Mac. (And if it doesn’t work, Manual Network Transfers offers manual techniques that can do the same job.)

On the Mac, you’ll find the Migration Assistant program in your Applications→Utilities folder. Before you open it, make sure your Mac and your PC are connected to the same network (WiFi or wired), as described in Chapter 15.

Now open Migration Assistant. Choose the first option: “From another Mac, PC, Time Machine backup, or other disk.” Click Continue. (Enter your password if you’re asked for it.)

When all is said and done, here’s what it accomplishes:

§ Transfers your email into Mail from Outlook, Outlook Express, Windows Mail, or Windows Live accounts (POP or IMAP). Your messages even show up correctly marked as having been read, replied to, and flagged (except if they originated in Windows Live).

§ Transfers your address book into Contacts from Outlook and Outlook Express contacts, and from Windows contacts in the Contacts folder on your PC.

§ Transfers your calendar into Calendar from Outlook’s calendar.

§ Transfers your iTunes collection into iTunes for the Mac from iTunes on Windows. Everything comes over, including music, photos, videos (but not rentals), and apps and games for iPhone/iPad/iPod Touch.

§ Transfers everything in your Windows Home folder into the corresponding Mac Home folder folders: Music, Pictures, Desktop, Documents, and Downloads.

§ Transfers your browser bookmarks and preferred home page into Safari from Explorer, Firefox, and Safari for Windows.

§ Transfers your account settings like language and even your desktop wallpaper.

All of this winds up in a new user account on your Mac. The migration program doesn’t make any attempt to merge your Windows world into your existing account on the Mac.

Now, the Migration Assistant app (in your Utilities folder) represents only the Mac end of this transaction. You also need the Windows end.

For that, download the free Windows Migration Assistant program. It’s waiting at www.apple.com/migrate-to-mac. Install it on your PC, which is a matter of clicking through three screens. In your Control Panel, turn off Windows Updates.

Now you’re ready to begin.

1. Make sure the PC and the Mac are on the same network.

It can be a WiFi network, but you’ll get a much faster transfer, with much less risk of interference, if you connect them to a wired network. For example, connect each with an Ethernet cable to your router.

2. On the PC, open the Windows Migration Assistant program that you downloaded. Click Continue.

The PC is now ready for action.

3. On the Mac, quit all programs. In your Applications→Utilities folder, open the Migration Assistant program.

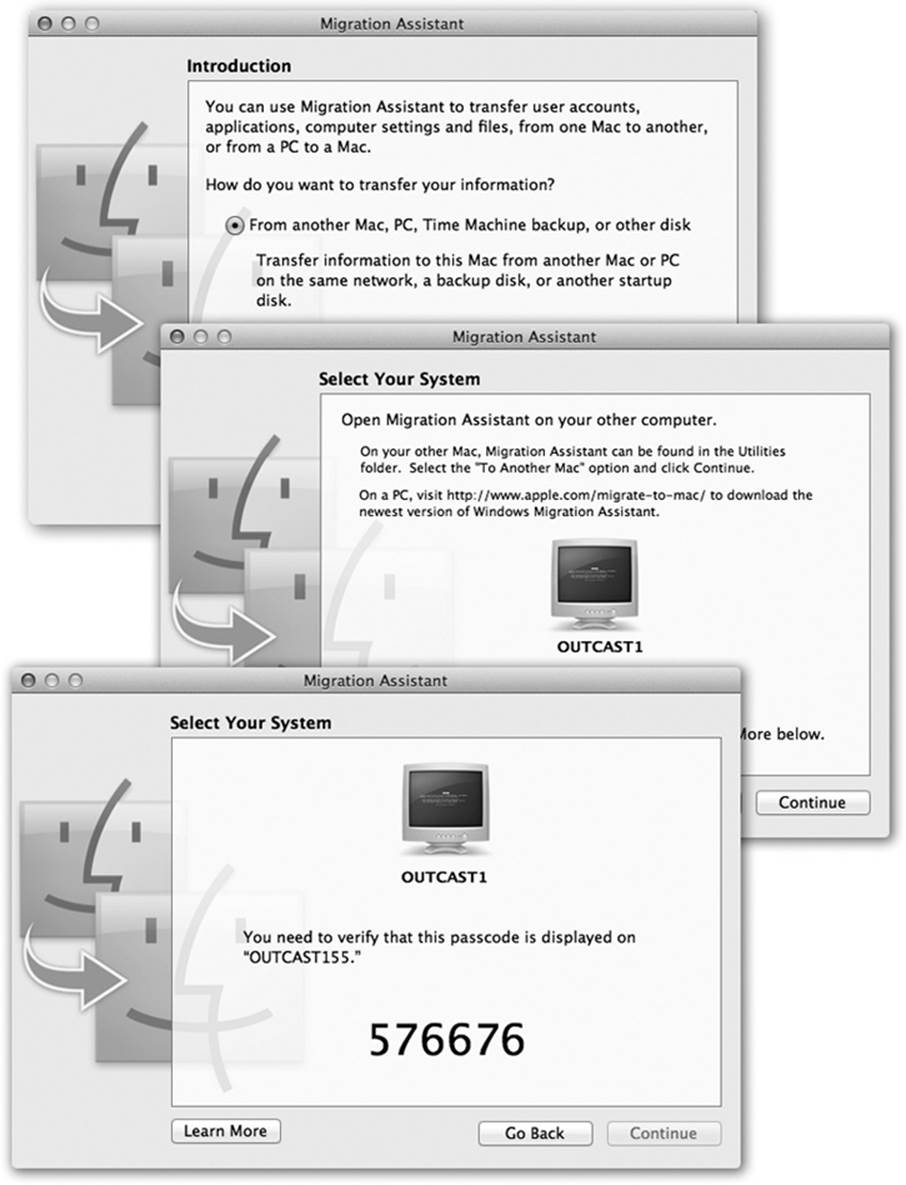

You’re offered two choices: “From another Mac, PC, Time Machine backup, or other disk” and “To another Mac” (see Figure 6-1).

4. On the Mac, click “From another Mac, PC, Time Machine backup, or other disk.” Click Continue. Provide your name and password, and click Continue again. Click “From another Mac or PC,” and click Continue.

At this point, your Mac should “see” the PC on the network. You’ll know, because you’ll see the PC’s name and icon in the dialog box shown in Figure 6-1, middle.

Figure 6-1. Here’s the Mac’s view of the Windows Migration Assistant procedure. Top: Tell it you’re transferring data from a PC. Middle: The Mac sees the PC on the network and displays its name and icon. Bottom: Here’s the passcode that, if you’re lucky, also shows up on the PC’s screen. (You don’t have to type it in anywhere, so it’s really not a passcode.)

5. Click Continue.

On the Mac, you see something like Figure 6-1, bottom: a big passcode. On the PC, you’re supposed to see a matching passcode.

If you don’t see the passcode on the PC, then something—your firewall, your antivirus program, Migration Assistant flakiness—is getting in the way. You may have to opt for the manual procedures described on Manual Network Transfers.

6. If you see the passcode on the PC’s screen, then click Continue.

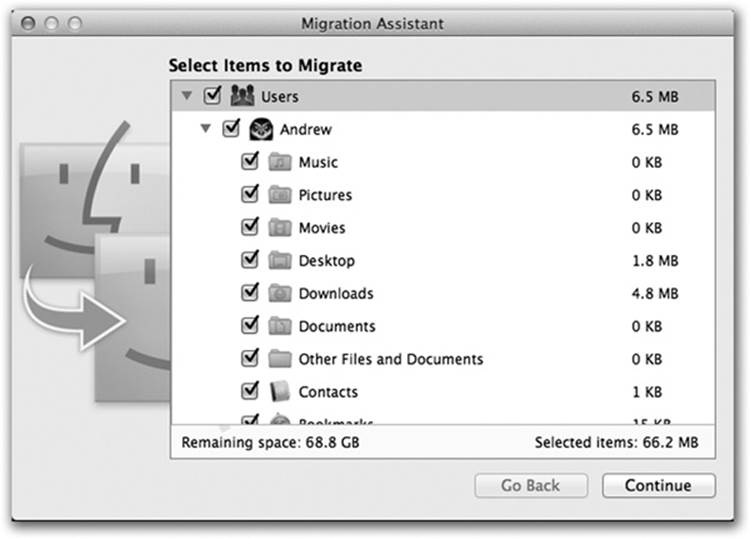

After a few minutes of whirring and thinking, the Mac displays a list of files that it can transfer from the PC (Figure 6-2).

Figure 6-2. The Mac shows the stuff on your PC. These include checkboxes for the other user accounts, but you can’t transfer them right now—it’s a one-account-at-a-time thing. To transfer someone else’s stuff, you’ll have to log into your PC as that person and repeat this whole procedure. The copying process can take a very long time—hours. The “time remaining” indicator may not be especially accurate.

7. On the Mac, turn on the checkboxes of the items you want copied. Click Continue to begin the transfer.

If all goes well, after a few hours, the Mac says, “Your information has been transferred successfully.”

8. On the Mac, click Quit.

If you choose ![]() →Log Out, you’ll see that there’s a new account on your Mac, named after the account you transferred from the PC. If you try to sign into it, you’re asked to provide a password for this new Mac account. (If you didn’t want your Windows stuff to wind up in a new Mac account, then you can always copy it back into your main account using the Users→Shared folder as a tunnel between accounts.)

→Log Out, you’ll see that there’s a new account on your Mac, named after the account you transferred from the PC. If you try to sign into it, you’re asked to provide a password for this new Mac account. (If you didn’t want your Windows stuff to wind up in a new Mac account, then you can always copy it back into your main account using the Users→Shared folder as a tunnel between accounts.)

TIP

The Migration Assistant puts all your mail into Apple’s Mail program, the one described in Chapter 11. If you’d prefer to use Microsoft Outlook for the Mac as your email program, here are the steps for transferring the mail stash from Mail to Outlook: http://j.mp/xtsGwi.

Manual Network Transfers

As you may have guessed from the paragraphs above, Macs and PCs can “see” each other on a network (wired or wireless). Seated at the Mac, you can open or copy files from any folders you’ve shared on a PC. In fact, you can go in the other direction, too: Your old PC can see shared folders on your Mac.

Chapter 15 offers a crash course in setting up a network. When it’s all over, you’ll be seated at the Mac, looking at the contents of your Windows PC in a separate window. At that point, you can drag whatever files and folders you want directly to the proper places on the Mac, as described onTransfers by Dropbox.

Transfers by Disk

Another way to transfer Windows files to the Mac is to put them onto a disk that you then pop into the Mac. (Windows can’t read all Mac disks without special software, but the Mac can read Windows disks.)

This disk can take any of these forms:

§ An external hard drive or iPod. If you have an external hard drive (USB or IEEE 1394, what Apple calls FireWire), you’re in great shape. While it’s connected to the PC, drag files and folders onto it. Then unhook the drive from the PC, attach it to the Mac, and marvel as its icon pops up on your desktop, its contents ready for dragging to your Mac’s built-in hard drive. (The Mac can read Windows disks and flash drives, which use unappetizingly named formatting schemes like FAT32 and NTFS, but Windows can’t read Mac hard drives or flash drives.)

Most iPods work great for this process, too; they can operate as external hard drives—even the iPod Nano. For details, see Via Flash Drive.

§ A Time Capsule. An Apple Time Capsule is a sleek, white box that contains a huge hard drive plus a wireless base station. The idea, of course, is to create a WiFi network for your house or office and include a built-in disk for backing up all your computers, automatically and wirelessly.

That also means the Time Capsule makes a great transfer station between a PC and a Mac, since its icon shows up on the desktops of both.

§ A USB flash drive. These small keychainy sticks are cheap and capacious, and they work beautifully on both Macs and PCs. Like a mini-external hard drive, a flash drive plugs directly into your USB port, at which point it shows up on your desktop just like a normal disk. You copy files to it from your PC, plug it into your Mac, and copy the files off, just like you would for any other disk. And you’re left with a backup copy of the data on the drive itself.

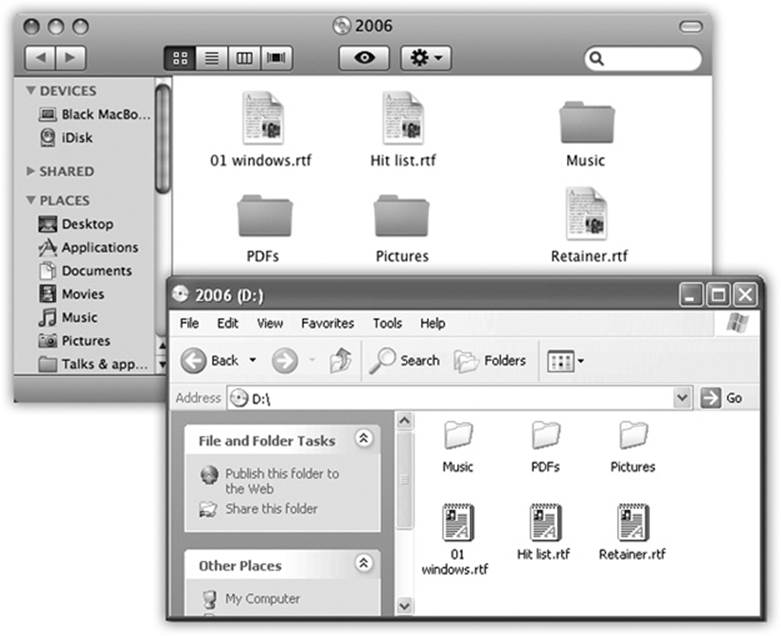

§ A CD or DVD. If your Windows PC has a CD or DVD burner, here’s another convenient method: Burn a disc in Windows, eject it, and then pop it into the Mac (see Figure 6-3). As a bonus, you wind up with a backup of your data on the disc itself. CDs and DVDs use the same format on both kinds of computers, so you should have very little problem moving these between machines.

NOTE

If you’re given a choice of file format when you burn the disc in Windows, choose ISO9660. That’s the standard format that the Macintosh can read.

Figure 6-3. Burned CDs generally show up with equal aplomb on both Mac and Windows, regardless of which machine you used to burn it. Here’s a CD burned on a Windows XP machine (bottom), and what it looks like on the Mac (top)—same stuff, just a different look and a different sorting order. Either way, you can drag files to and from it, rename files, delete files, and so on.

§ Move the hard drive itself. This is a grisly, technical maneuver best undertaken by serious wireheads—but it can work. You can install your PC’s hard drive directly into a Power Mac or Mac Pro, as long as it was prepared using the older FAT or FAT32 formatting scheme. (The Mac can handle FAT hard drives just fine, but it chokes with NTFS hard drives.)

When you insert a Windows-formatted disk, whatever the type, its icon appears in the Mac’s Computer window (or on the desktop, if you’ve turned on the relevant checkbox in the Finder→Preferences→General tab).

Transfers by Dropbox

Dropbox is a free service (for up to 2 gigabytes) that puts a magic folder on your desktop—of every machine you own. Including your tablet or phone.

Anything you put in there magically shows up in all the others. There’s no reason you couldn’t transfer your stuff from PC to Mac, 2 gigabytes at a time, by dragging it into your Dropbox folder on the PC, and then opening the Dropbox folder on the Mac a few minutes later and moving yourfiles from there into their new homes.

Transfers by File-Sending Web Site

Free Web sites like yousendit.com and sendthisfile.com are specifically designed for sending huge files from one computer to another, without worrying about email file attachments or size limits.

On the Windows PC, zip up your files into a great big .zip file. Upload it to one of these free sites, and provide your Mac’s email address.

On the Mac, click the link that arrives by email—and, presto, that huge zip file gets downloaded onto your Mac. It’s free, there’s no file-size limit, and you can download the big file(s) at any time within three days of sending them. The only price you pay is a little bit of waiting while the stuff gets uploaded and then downloaded.

TIP

If you have your own Web site—a .com of your own, for example, or a free site through a university—you can also use that Web space as a transfer tool. Follow the uploading instructions you were given when you signed up for the space. (Hint: It usually involves a so-called FTP program.) Then, once all your files are on the site, download them onto your Mac.

Transfers by Email

Although sending files as email attachments might seem to be a logical plan, it’s very slow. Furthermore, remember that many email providers limit your attachment size to 5 or 10 megabytes. Trying to send more than that at once will clog your system. If you’ve got a lot of stuff to bring over from your PC, then use one of the disk- or network-based transfer systems described earlier in this chapter.

But for smaller transfer jobs or individual files, sending files as plain old email attachments works just fine.

Where to Put Your Copied Files

Getting your PC files onto the Mac is only half the battle. Now you have to figure out where they go on the Mac.

Here’s the short answer: Everything goes into your Mac’s Home folder. (Choose Go→Home, or click the ![]() icon in your Sidebar.)

icon in your Sidebar.)

Some of the more specific “where to put it” answers are pretty obvious:

§ My Documents. Put the files and folders from the PC’s My Documents folder into your Home→Documents folder. Here’s where you should keep all your Microsoft Office files, PDF files, and other day-to-day masterpieces.

§ My Music. Your Windows My Music folder was designed to hold all your MP3 files, AIFF files, WAV files, and other music. As you could probably guess, you should copy these files into your Mac’s Home→Music folder.

After that, you can import the music directly into iTunes. If you used iTunes on your PC, for example, see the steps on iTunes Music for specific transfer instructions.

If you used some other music program on your PC (like Windows Media Player or MusicMatch), things are a little different. On your Mac, choose iTunes→Import, and navigate to the folder that contains all your music. (In either case, click Choose in the resulting dialog box.)

§ My Pictures. Windows also offers a My Pictures folder, which is where your digital camera photos probably wound up. OS X has a similar folder: the Home→Pictures folder.

Here again, after copying your photos and other graphics faves over to the Mac, you’re only halfway home. If you fire up iPhoto (in your Applications folder), choose File→Import, and choose the Pictures folder, you’ll then be able to find, organize, and present your photos in spectacular ways.

§ My Videos. The My Videos folder of Windows XP and later versions contains the video clips you’ve downloaded from your camcorder (presumably so that you can edit them with, for example, Microsoft’s Movie Maker software). Once you’ve moved them to your Home→Movies folder, though, you’re in for a real treat: You can now edit your footage (if it’s digital footage) with iMovie, which, to put it kindly, runs rings around Movie Maker.

Other elements of your Windows world, though, are trickier to bring over. For example:

Desktop Pictures (Wallpaper)

Especially in recent versions of Windows, the desktop pictures, better known in the Windows world as wallpaper, are pretty cool. Fortunately, you’re welcome to bring them over to your Mac and use them on your new desktop.

To find the graphics files that make up the wallpaper choices in Windows (version Me or later), proceed like this:

1. Open My Computer, double-click your hard drive’s icon, and open the Windows or WINNT folder.

If you see a huge “These files are hidden” message at this point, or if the window appears empty, click “Show the contents of this folder” or “View the entire contents of this folder” at the left side of the window.

2. In the Windows or WINNT window, open the Web folder.

You’re looking for a folder inside it called Wallpaper.

3. Open the Wallpaper folder.

It’s filled with .bmp or .jpg files ready for you to recycle for use on the Mac. See Bluetooth for instructions on choosing wallpaper for your Mac.

NOTE

In Windows 95 or 98, the wallpaper files are in your Program Files→Plus!→Themes folder instead.

Sound Effects

The Mac doesn’t let you associate your own sound effects to individual system events (Low Battery Alarm, Maximize, Minimize, and so on) as Windows does. It lets you choose one sound effect for all attention-getting purposes (Sound).

Still, there’s nothing to stop you from harvesting all the fun little sounds from your Windows machine for use as the Mac’s error beep.

WORKAROUND WORKSHOP: TRANSFERRING YOUR MAIL AND ADDRESS BOOK

If you’re lucky, you can use the Windows Migration Assistant to bring your PC’s files over to the Mac—including your email stash and your contacts. Those are very difficult to transfer manually—the files themselves require conversion—so if the Migration Assistant doesn’t work, you might wonder where to turn next.

Four solutions await you. None is free, fast, and easy—but each is either free, fast, or easy.

The Thunderbird method. Thunderbird is the free, open-source email companion to the Firefox Web browser. Among other virtues, it can easily open Outlook or Outlook Express email collections on the PC—and convert them into formats that Mac email programs can use. You can find step-by-step instructions online—for example, at http://j.mp/1dZ657s.

The O2M solution. For several years, the easiest and most flexible method of transferring your email and contacts was a shareware program called O2M (short for Outlook2Mac). Unfortunately, the company that wrote it has disappeared without a trace. You might still be able to find a copy of O2M floating around online, though.

The 8Convert solution. For $14, you can buy 8Convert, a shareware program especially for extracting your data from Outlook (not Outlook Express). It handles your email (complete with attachments and date ranges that you choose), address book, and calendar; the online instructions (www.eighthoof.com) show you how to bring these three items into Mail, Contacts, and Calendar on the Mac. (Similar shareware: MessageSave, www.techhit.com.)

The Gmail trick. You can use an online (IMAP) email account as an intermediary between Outlook and the Mac.

Sign up for a free Gmail account. Then, in Windows, open Outlook and add your Gmail account. Now copy the mail folders from your Outlook list into the Gmail account. (Don’t drag-and-drop; that moves the messages instead of copying.) This process can take a very long time.

Then, in Mail on the Mac, add the same Gmail account, and after a while, presto: All your mail now shows up on the Mac.

To find them on the PC, repeat step 1 of the preceding instructions. But in the Windows or WINNT folder, open the Media folder to find the WAV files (standard Windows sound files).

Once you’ve copied them to your Mac, you can double-click one to listen to it. (It opens up in something called QuickTime Player, which is the rough equivalent of Windows Media Player. Press the space bar to listen to the sound.)

To use these sounds as error beeps, you’ll have to convert them from the PC’s WAV format into the Mac’s preferred AIFF format. You’ll find step-by-step instructions in the free downloadable appendix for this chapter, “Converting WAV Sounds to Mac Error Beeps.” It’s on this book’s “Missing CD” page at www.missingmanuals.com.

Bookmarks (Favorites)

Moving your Favorites (browser bookmarks) to a Mac is easy. The hardest part is exporting them as a file, and that depends on which browser you’ve been using on the PC.

§ Internet Explorer. Fire up Internet Explorer; choose File→Import and Export. (In Internet Explorer 7, click the double-star icon in the upper-left corner of the window. From the pop-up menu, choose Import and Export.)

When the Import/Export Wizard appears, click Next; on the second screen, click Export Favorites, and then click Next again. On the third screen, leave the Favorites folder selected, and click Next. Click Browse to choose a location for the exported bookmarks file. For now, save it to your desktop. Click Next, Finish, and then OK.

§ Firefox. In Firefox, choose Bookmarks→Organize Bookmarks. In the Bookmarks Manager window, choose File→Export. Save the Bookmarks file to your desktop.

TIP

Firefox is available for the Mac, too (www.getfirefox.com). You can transfer your exported Windows bookmarks file into the Mac version by choosing Bookmarks→Manage Bookmarks; then, in the Bookmarks Manager window, choose File→Import. Find and select the exported bookmarks file.

Or you can let Firefox synchronize your PC bookmarks with your Mac automatically and wirelessly. Details are at http://j.mp/1eH7PBI.

§ Chrome. In Chrome, use the Chrome menu (![]() ) on the toolbar. Select Bookmarks→Bookmark manager→Organize menu→Export bookmarks. Save the HTML file to your desktop.

) on the toolbar. Select Bookmarks→Bookmark manager→Organize menu→Export bookmarks. Save the HTML file to your desktop.

TIP

Chrome is available for the Mac, too (www.google.com/chrome). If you sign into your Google account on each computer (PC and Mac), you’ll find your bookmarks already magically present in the Mac version of Chrome. Your tabs, history, and other browser preferences are auto-synced, too.

Now you’ve got an exported Bookmarks file on your desktop. Transfer it to your Mac using any of the techniques described earlier in this chapter (network, email, whatever).

Now open the Mac’s Web browser, Safari (it’s in your Applications folder). Choose File→Import Bookmarks. Navigate to, and double-click, the exported Favorites file to pull in the bookmarks.

iTunes Music

If you’ve kept your Windows music collection in iTunes, you can transfer it to the Mac with everything intact: play counts, ratings, playlists, and so on.

Before you begin, though, you have to do some Windows housekeeping. On the PC, open iTunes and choose Edit→Preferences→Advanced. Turn on “Keep iTunes media folder organized” and “Copy files to iTunes media folder when adding to library.” Then choose File→Library→Organize Library, turn on Consolidate Files, and click OK. If the option called “Upgrade to iTunes Media organization” is available, then turn that on, too. (All these steps put all of your music and video files in the main iTunes Media folder, which you’ll copy to the Mac.)

You may have to wait for iTunes to complete these steps. Once they’re finished, copy the iTunes folder from your PC to the Mac. Here’s where to find it on the PC:

§ Windows XP. Documents and Settings→[your user name]→My Documents→My Music→iTunes

§ Windows Vista, Windows 7 or 8. [your user name]→Music→iTunes

Copy that entire iTunes folder to your Mac using one of the methods described in this chapter. It goes into your Home→Music folder.

If there is already an iTunes folder, it’s OK to replace it. (Unless, of course, you’ve imported music into the Mac version of iTunes; in that case, you’ll have to copy the Music files from it into the incoming PC’s iTunes folder.)

Now, when you open iTunes on the Mac, you’ll see your iTunes collection, safely transferred. All of it: music, videos, ratings, playlists, everything.

TIP

If you plan to abandon or sell your PC, don’t forget to “deauthorize” its iTunes account so that it doesn’t count as one of the five machines that are allowed to play your copy-protected iTunes songs. Do that by opening iTunes. From the Store menu, choose Deauthorize This Computer.

Document Conversion Issues

Most big-name programs are sold in both Mac and Windows flavors, and the documents they create are freely interchangeable.

Files in standard exchange formats don’t need conversion, either. These formats include JPEG (the photo format used on Web pages), GIF (the cartoon/logo format used on Web pages), PNG (a newer image format used on Web pages), HTML (raw Web-page documents), Rich Text Format (a word-processor exchange format), plain text (no formatting), QIF (Quicken Interchange Format), MIDI files (for music), and so on.

One reason: both Windows and OS X use filename extensions to identify documents. (“Letter to the Editor.doc,” for example, is a Microsoft Word document on either operating system.) Common suffixes include these:

|

Kind of document |

Suffix |

Example |

|

Microsoft Word |

.doc, .docx |

Letter to Mom.doc |

|

text |

.txt |

Database Export.txt |

|

Rich Text Format |

.rtf |

Senior Thesis.rtf |

|

Excel |

.xls, .xlsx |

Profit Projection.xls |

|

PowerPoint |

.ppt, .pptx |

Slide Show.ppt |

|

FileMaker Pro |

.fp5, .fp6, .fp7… |

Recipe file.fp7 |

|

JPEG photo |

.jpg, .jpeg |

Baby Portrait.jpg |

|

GIF graphic |

.gif |

Logo.gif |

|

PNG graphic |

.png |

Dried fish.png |

|

Web page |

.htm, .html |

Index.htm |

NOTE

Recent versions of Microsoft Office for Mac and Windows offer a more compact file format ending with the letter x. For example, Word files are .docx, Excel files are .xlsx, and so on. The older, more widely compatible format doesn’t have the x (.doc, .xls, and so on).

The beauty of OS X is that most Mac programs add these file name suffixes automatically and invisibly—and recognize such suffixes from Windows with equal ease. You and your Windows comrades can freely exchange documents without ever worrying about this former snag in the Macintosh/Windows relationship. (You may, however, encounter snags in the form of documents made by Windows programs that don’t exist on the Mac, such as Microsoft Access. Chapter 7 tackles these special cases one by one.