Troubleshooting Your Mac: A Joe On Tech Guide (2015)

Chapter 3. Learn Troubleshooting Basics

If I were teaching you how to cook, I’d start by making sure you knew the basic techniques you’d be repeating many times: how to julienne vegetables, deglaze a pan, cream butter, roast poultry, and so on. That way, when we got to specific recipes later, I could simply say, “sweat the aromatics in butter and purée the tomatoes” without having to explain the meanings of words like “sweat,” “aromatics,” and “purée.”

I want to do the same thing in this chapter: make sure you have a grasp of certain procedures that come up in many different Mac troubleshooting tasks. Then, when I describe the specific steps you’ll follow to solve various problems, I can say, “start up in safe mode” without having to spell out that process every time. And of course, you can always follow links back here if you need a reminder of what I’m talking about.

Note: To be crystal clear, I’m not saying you should try every procedure in this chapter right now if your Mac is misbehaving! This is a reference chapter to teach you various procedures you may use as part of the troubleshooting steps I cover later.

If you’ve been using Macs for a while, you may raise your eyebrows at some of the procedures just ahead. “Restart Your Mac? Is he kidding? Who doesn’t know how to restart a Mac?” But please read those sections anyway, because they include details that may not be obvious (such as what to do if the usual means of restarting doesn’t work).

Force-Quit an App

When an app gets stuck and its regular Quit command won’t work, you can usually quit it using OS X’s Force Quit feature. To do this, choose Apple → Force Quit (or press ⌘-Option-Escape). Select the app you want to quit and click Force Quit. You can then close the Force Quit Applications window.

Tip: You can often force-quit a stuck app without the Force Quit Applications window. One way is to Option-right-click (or Control-Option-click) the offending app’s Dock icon and choose Force Quit from the pop-up menu. Or, to force-quit the foreground app immediately, press ⌘‑Option-Shift-Escape.

Sometimes, an app keeps running even after you use the Force Quit command. When this happens, a second attempt at force-quitting nearly always does the trick. Close the Force Quit Applications window if it’s still open, and repeat the force-quit procedure.

If even the second attempt doesn’t work, or if you can’t bring up the Force Quit Applications window, your best bet is to Restart Your Mac.

Note: Finder appears in the Force Quit Applications window along with your other apps, but when you select it the button changes from Force Quit to Relaunch. That’s because OS X is designed so that the Finder is always running. If you quit it—which you may need to do if it gets stuck—it automatically attempts to open again.

Restart Your Mac

Restarting is the most powerful Mac troubleshooting technique I know. This simple procedure can resolve a huge variety of crashes, hangs, and other problems. It may not be the first thing you should try (because it sometimes takes a few minutes), but it should certainly be high on your list.

When the need to restart arises, try each of these methods in turn until you succeed:

1. The menu command: Choose Apple → Restart. When the confirmation alert appears, click the Restart button.

Tip: Another way to restart is to press your Mac’s power button for about three seconds, which will cause your Mac to display a dialog with four buttons (Restart, Sleep, Cancel, and Shut Down). When this dialog appears, you can either click the Restart button or simply press the R key to restart immediately, without the confirmation alert.

OS X then instructs all running apps and background processes to quit. After a few seconds (or, in some cases, as long as a few minutes—if whatever’s running takes a while to respond), the screen goes blank, the startup chime plays, and the Mac restarts.

In some situations, restarting in this way isn’t possible. Perhaps the Apple menu won’t drop down, or your Mac is completely frozen and won’t respond at all. Or maybe the Restart command appears to take, but 10 minutes later the machine is still chugging away. When this happens, move on to the next step.

2. The keyboard shortcut:

§ If your keyboard has a power button, hold down Command and Control and press the power button.

§ If your keyboard doesn’t have a power button, hold down Command and Control and press the eject key (typically found in the upper-right corner of the keyboard; if it’s not labeled, try either F12 or F15). Usually this method causes your Mac to restart immediately (which means you’ll lose any unsaved work).

3. The brute-force method: If neither of the above methods is successful, press and hold the Mac’s power button (sometimes the power button on older Apple monitors works too) for approximately 10 seconds, or until the power light goes out completely. (If you don’t hold it long enough, you may just put your Mac to sleep, as indicated by a pulsating power light.) Then press the power button again to turn your Mac back on.

Log In to Another User Account

Earlier, I suggested setting up an additional administrative account that you can use for troubleshooting (see Set Up Another User Account). You should log in to that account if you suspect that some app or process in your main user account is causing problems with your Mac. To do this:

1. Choose Apple → Log Out username. Do not use Fast User Switching (that is, choosing a different username from the user menu, which results in the first account remaining logged in), as software launched from your current account could potentially cause system-wide problems.

2. Select the secondary user account (or enter its name), enter its password, and press Return.

3. Check to see if whatever problem you were experiencing still exists. If not, you know that something in your previous user account (most likely something within your main user account’s home folder) is the cause of the problem.

4. When you’re done with your test, repeat these instructions to log in under your normal account.

Start Up from Another Volume

If your main startup volume has problems that can’t be repaired while OS X is running from it—or if the drive dies completely and you need to start from a bootable duplicate—use one of these procedures to start up from another volume.

Tip: For ideas on what type of hardware to use for the following procedures, read Acquire a Secondary Startup Volume, earlier.

Start in OS X Recovery

Restart while holding ⌘-R to start from the hidden Recovery HD volume (see Acquire a Secondary Startup Volume); this puts you into a mode Apple calls OS X Recovery. Once in OS X Recovery, you can select Disk Utility (the most common option), Restore from Time Machine Backup, Reinstall OS X, or Get Help Online, and then click Continue.

But wait! It gets even more interesting. All Macs introduced in 2011 or later, as well as some 2010 Macs, also support OS X Internet Recovery. (See a list of pre-2012 Macs that can be made to support OS X Internet Recovery via a firmware update at alt.cc/4j.) This means that, as long as your Mac is connected to the internet, you can boot it and use OS X Recovery even if your disk is damaged or missing (or you installed a new, completely blank disk).

The way it works is that when you restart while holding down ⌘-R, your Mac first looks for a valid Recovery HD volume; if it can’t find one (because it’s missing or the portion of the disk it sits on is damaged), your Mac connects to Apple’s servers, downloads a new Recovery HD disk image, and boots from that. (If you use Wi-Fi to connect to the internet, you may be prompted to select a network and enter a password.) To read more about OS X Internet Recovery, see Apple’s support article at alt.cc/4k.

Start from a Local Volume

If your secondary startup volume is on another hard drive, a flash drive or SD card, an Apple USB Software Reinstall Drive, or a partition of your main disk, follow these steps:

1. If you haven’t already done so, attach the drive to your Mac.

2. Restart, holding down the Option key until icons for all the valid startup volumes appear on the screen; this screen is what Apple calls Startup Manager. (If your Mac refuses to display the startup volumes, restart again, this time holding down ⌘-Shift-Option-Delete.)

3. Using the mouse or trackpad, or the arrow keys on the keyboard, select the volume from which you want to boot. Then press Return.

Note: When you choose a new startup volume using the method described here, that choice applies only once. The next time you restart, if you don’t hold down any extra keys, you’ll start up from your previously selected volume. To make the change in startup volume persist past a single restart, go to System Preferences → Startup Disk and pick a new startup volume.

Start from a CD or DVD

Most Mac models no longer include optical drives, but if you have an older Mac with a built-in SuperDrive (or a newer Mac with an external SuperDrive), you can—if none of the other options are available—start up from a boot CD or DVD included with your Mac by following these steps:

1. If your Mac is running, insert the disc containing a bootable copy of OS X. Then choose Apple → Restart, and skip to step 3.

2. If your Mac is off, press the power key and immediately insert the disc. (On some Macs, you may have to press the Eject button on your keyboard to open the drive tray. Do this, and insert the disc, as quickly as you can.)

3. Immediately hold down the C key on the keyboard.

4. When the gray Apple logo appears in the center of the display, release the C key.

Keep in mind that the startup process takes considerably longer with a CD or DVD than it does with a hard disk.

Start from a Remote Disc

Most recent Macs lack a built-in optical drive. A few models included a USB Software Reinstall Drive, but if you don’t have one, you still have another option. Most Macs with no optical drive can boot over an Ethernet or Wi-Fi network from a startup CD or DVD loaded on another computer—Mac or PC—on your network.

To do this, you must first install the Remote Disc software (included with your Mac, or downloadable from alt.cc/ax) on the other computer, following these directions on Apple’s website: alt.cc/ay. Then, insert the disc you want to boot from in the other computer. On your Mac, select that disc in System Preferences → Startup Disk and restart.

Run Disk Repair Utilities

All the disk repair utilities I mention in this book are easy to use. In general, it’s simply a matter of booting from a secondary volume, running the app (some of them launch automatically), selecting a drive (or volume), and clicking a button. (Some apps let you choose among a variety of tests to perform; when in doubt, run them all!) Consult the documentation included with your utility for details.

As an example, here’s how to repair a disk in Disk Utility. The instructions differ depending on which version of OS X you’re running.

Use Disk Utility in El Capitan

If your Mac is running El Capitan, follow these steps:

1. Open Disk Utility (in /Applications/Utilities).

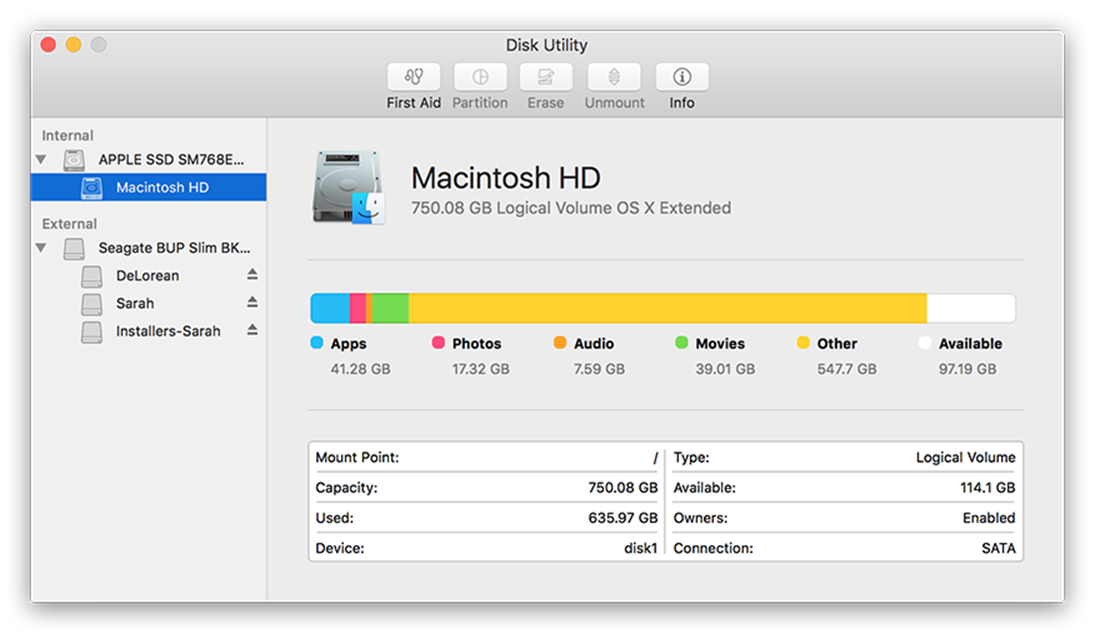

2. In the list on the left, select your startup volume (if it’s not already selected, which it most likely is). Note that volume names are indented underneath the names of the physical devices on which they reside (see Figure 1). Figure 1: Disk Utility indents volume names underneath device names; here, a volume is selected.

Figure 1: Disk Utility indents volume names underneath device names; here, a volume is selected.

3. Click the First Aid button on the toolbar, and then click Run. Disk Utility examines your disk and attempts to repair it if necessary.

4. When the repair is finished, click Done and quit Disk Utility.

Note: If you’re unable to start your Mac normally, restart while holding down ⌘-R to boot into OS X Recovery. Then select Disk Utility, click Continue, and pick up from step 2 above.

Use Disk Utility in Yosemite or Mavericks

In Yosemite or Mavericks, Disk Utility can’t repair the volume you booted from, so you’ll have to use a different procedure. Follow these steps:

1. If your secondary startup volume (see Acquire a Secondary Startup Volume) is on a physical device (such as a hard drive, a flash drive, or an SD card), attach it now; if it’s on a CD or DVD, insert it now.

2. Restart (see Restart Your Mac). If you’re using OS X Recovery, hold down ⌘-R until the gray Apple logo appears; if you’re using a startup CD or DVD, hold down the C key instead. Otherwise, hold down the Option key until icons for all the valid startup volumes appear on the screen, select your secondary startup volume, and press Return.

3. Locate and open Disk Utility. If you’re starting in OS X Recovery, you can simply select it in the list that appears and click Continue. Otherwise, open it from /Applications/Utilities.

4. In the list on the left, select your startup volume. Note that volume names are indented underneath the names of the physical devices on which they reside.

5. Click Repair Disk.

Disk Utility examines your disk and attempts to repair it if necessary. When it’s finished, you can quit Disk Utility and restart your Mac normally.

Erase and Restore from a Backup

In the unlikely event that neither Disk Utility nor a third-party utility can repair the problems with your disk, you might be able to recover data from it using specialized data recovery software or an expensive data recovery service such as DriveSavers (drivesavers.com). But if you already have an up-to-date backup, neither of those approaches is worth your time or effort. Instead, you should erase the disk (assuming the hardware is still OK—see How to Tell Whether You Need a New Hard Drive) and start over:

· If you have a bootable duplicate, the process is easy: start up from the duplicate, use Disk Utility to erase the malfunctioning disk, and then use your backup software to copy the backup back onto the erased disk.

· If you don’t have a duplicate, make one if possible. (Read Back Up Your Mac Regularly.) If your Mac won’t boot normally, you might still be able to boot it in target disk mode if it has a Thunderbolt or FireWire port. To do this, restart and hold down the T key until the Thunderbolt or FireWire icon screensaver appears. Run the appropriate cable to another Mac, and use a tool like Carbon Copy Cloner or SuperDuper! along with an external hard disk attached to that Mac to make a duplicate of the ailing Mac’s disk. Assuming the ailing Mac’s disk is functional, use Disk Utility to erase the malfunctioning disk, and use your backup software to copy the backup back onto the erased disk.

· If you have a Time Machine backup, you can restart while holding down ⌘-R to boot into OS X Recovery, and click Restore from Time Machine Backup. Click Continue and follow the instructions to restore your latest backup.

· If you can’t make a duplicate and don’t have a complete Time Machine backup, back up your files as best you can. Then restart while holding down ⌘-R to boot into OS X Recovery, click Disk Utility, and then click Continue. In the list on the left, select the volume you want to erase. Volume names (there may be one or more per disk) are shown indented under the disk name, so be sure to select one of the indented icons. Click Erase, and confirm your selection. Be aware that this will erase everything on that disk—though at this point you may have no other choice. Then install OS X normally.

How to Tell Whether You Need a New Hard Drive

When I refer to disk errors that an app such as Disk Utility can repair, I’m referring to data errors. That is, some of the information on the disk is damaged—for example, the hidden directory files that track where the many pieces of each file and folder reside may be corrupted. This sort of thing happens often, and it’s usually easy for a utility to figure out how to restore the errant data to its correct state.

However, hard drives (unlike SSDs) are mechanical devices that spin quite fast. As with any such device, forces such as heat and friction can eventually cause a hardware failure—for example, the read/write heads won’t move properly, or they’ve collided with the magnetic platters, causing damage; the motor or bearings have worn out; or some other tiny component has gone kaput. Drive failures sometimes happen due to factory defects, but even with perfect manufacturing and under optimal conditions, a typical hard drive might last only a few years.

How can you tell whether a hard drive is physically damaged? Here are a few signs:

· Unusual sounds: Unlike the typical gentle clatter of a healthy hard drive, an unusually loud, repetitive clicking sound often means the drive is damaged. A whine or squeal is also a bad sign.

· Inability to boot: If your Mac can’t boot from the drive—even after running disk repair utilities—there’s a good chance the drive is toast. See Your Mac Stalls During Startup for more details.

· Disk repair failure: If multiple disk repair apps report that your disk is damaged and can’t be repaired, they’re almost certainly right.

· S.M.A.R.T. warnings: Most built-in hard drives (and some, but not all, SSDs) have sensors that report their health to your Mac. If you select the drive (the unindented, physical device) in Disk Utility and look at the bottom of the window next to “S.M.A.R.T. status,” the words “About to Fail” mean exactly that.

In all such cases, I’m sorry to say there’s usually nothing you can do but replace the drive and then restore your data from a backup (refer back to Erase and Restore from a Backup).

Repair Permissions

Every file on your Mac has a collection of settings specifying which users can perform various actions with it (including reading, writing, and executing). The files that make up OS X itself (including some Apple-installed apps) have very particular permission settings, and if they get changed from what they were originally, things can go wrong. For example, apps may refuse to open, printing may stop working, and you may even be unable to log in.

Permissions don’t change themselves. Something has to happen to change them—such as running an improperly written installer or doing injudicious fiddling in Terminal. But whatever the cause, out-of-whack permissions can be nasty.

In El Capitan, Apple has addressed this long-standing problem in two ways. First, OS X now protects certain critical directories so that their contents (including permissions) can never be changed except by the Apple installer. Second, every time you run the Apple installer (such as when you update OS X to a newer version), the installer checks permissions for Apple-installed files and resets any that are incorrect. As a result, if you’re running El Capitan, there’s nothing more for you to do here (you can no longer repair permissions yourself), so you can skip ahead now to Start Up in Safe Mode.

If you’re still running Yosemite or Mavericks, however, it’s a different story. Disk Utility in OS X 10.10 and earlier has a command to restore certain permissions to what they were originally. This command affects only about 50 software packages (including the core elements of OS X). It doesn’t change the permissions for any third-party software, and it only resets permissions to what they were originally—which could, in theory, have been wrong. So it’s not the cure-all that many pundits have proclaimed it to be, and I don’t recommend it as apreventive maintenance procedure. But it can solve real problems, including problems that involve third-party software (which depends on parts of OS X that must, in turn, have the correct permissions).

To repair your permissions, follow these steps:

1. Open Disk Utility (in /Applications/Utilities).

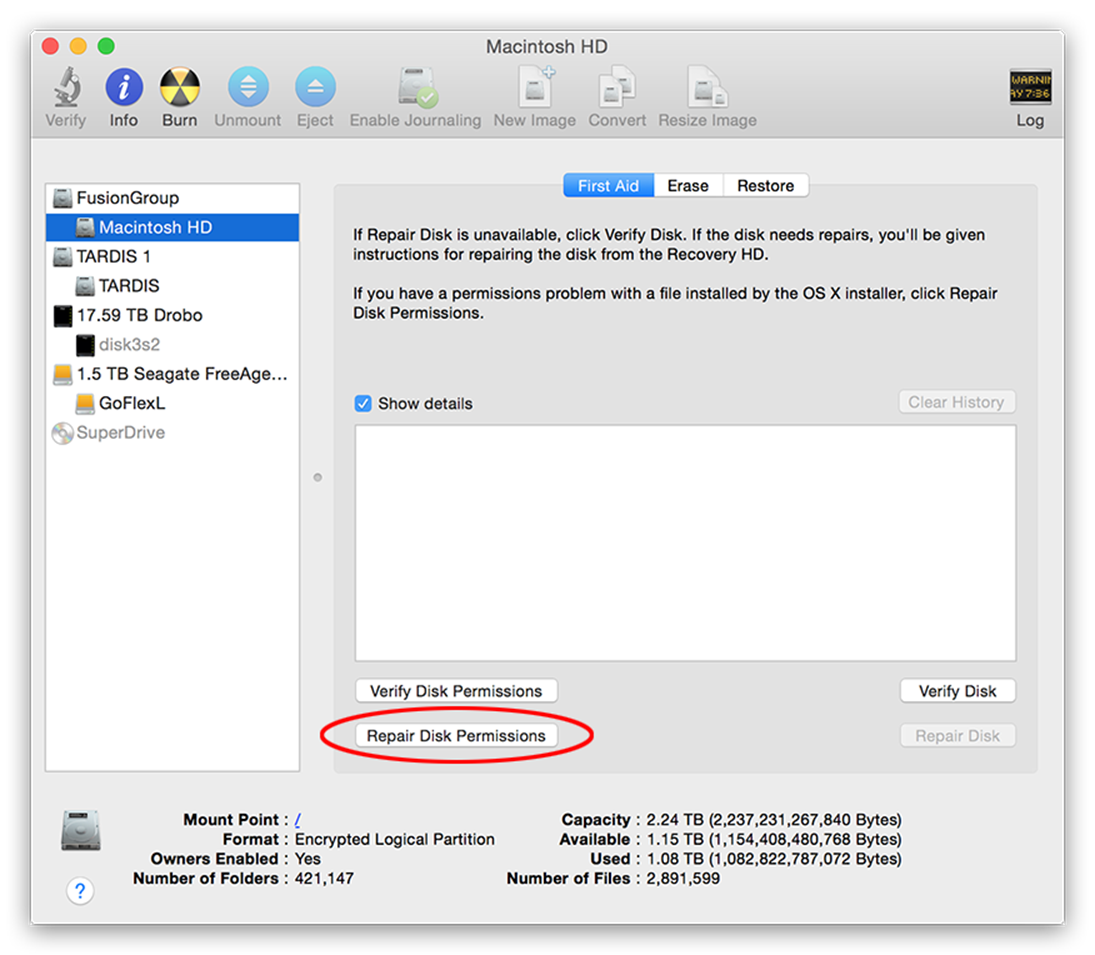

2. In the list on the left, select the volume whose permissions you want to reset, as shown in Figure 2, where I’ve selected my main startup volume. (Permissions can be repaired only for volumes containing a bootable copy of OS X.) Figure 2: Repair permissions by selecting a disk and clicking the Repair Disk Permissions button.

Figure 2: Repair permissions by selecting a disk and clicking the Repair Disk Permissions button.

3. In the First Aid pane, click Repair Disk Permissions.

Disk Utility displays messages about what permissions, if any, it resets in the status area.

Start Up in Safe Mode

As you use your Mac over a period of months and years, chances are you’ll install a variety of third-party software. Some of this software may include components that operate at a low level and must be running in the background all the time—things like drivers for third-party input devices, certain backup apps, audio capture software, and utilities that monitor your Mac’s performance. All these things may load and run every time your start your Mac, without your ever being aware of them. When they work, they’re great, but if something goes wrong with one of them, it’s not always clear what the problem is or how to turn off the offending software.

For reasons like this, Apple provides a special way to boot into OS X called safe mode; entering that mode is called performing a safe boot. A safe boot temporarily disables most of these third-party items (as well as several Apple products). It also disables any login items (apps or documents listed in System Preferences → Users & Groups → Login Items), which normally open when you log in. Safe mode also clears certain caches that would otherwise load at startup. By turning off all these items, you can eliminate many potential glitches, and if the problem you were experiencing stops after a safe boot, you have some important clues as to what the culprit is.

Safe Mode Details

Apple’s website has complete information about what happens (or doesn’t) during a safe boot. See alt.cc/ab.

To perform a safe boot, follow these steps:

1. Restart your Mac.

2. As soon as you hear the startup chime, press the Shift key and hold it down until the gray Apple logo appears on the screen.

Your Mac will complete the startup process, which may take considerably longer than usual. You’ll eventually see the words “Safe Boot” on the screen—possibly within the login window, depending on which version of OS X you’re running.

Note: If you have FileVault enabled, the instructions are slightly different. At step 2, hold the Shift key down until you see the login screen. Unlock FileVault as usual, and after a few moments you’ll see a progress bar slowly make its way across the bottom of the screen. Then the dark-gray login screen appears, with “Safe Boot” in red on the right side of the menu bar. Log in normally, do whatever you need to do, and restart to return to your Mac’s normal operating mode.

Check Preference Files

When an app starts acting funny, one of the first things to suspect is a damaged preference file.

Before you can disable a preference file, you must find it—and that’s sometimes easier said than done. Most preference files live in one of five folders:

· ~/Library/Preferences or /Library/Preferences

· ~/Library/Application Support/app or developer name or

/Library/Application Support/app or developer name

· ~/Library/Containers/app name/Data/Library/Preferences, where app name is something like com.apple.mail (more on that format in a moment)

These folders can contain hundreds or even thousands of items, and they may not conform to any obvious organizational scheme.

Apple recommends that preference files follow a standard naming convention, known as reverse-domain name style. You take a company’s domain name and reverse it—apple.com turns into com.apple—and then you add the name of the app. Finally, you add the extensionplist (for property list). So, com.apple.mail.plist is the preference file for Mail, and com.microsoft.Word.plist is the preference file for Word. That’s a bit weird, but at least it makes sense.

Unfortunately, this system doesn’t always work, for one of these reasons:

· Some developers use their own naming conventions.

· Some apps have several different preference files, each for a different sort of data. These files might be stored in a folder inside your Preferences folders, or they might not—and if they are in a folder, there’s no telling what that folder might be named. (The name of the app and the name of the developer are two good initial guesses.)

· Apps may change the formats or names they use for preference files from one version to the next, making it unclear which of several candidates is the right one.

· Your Preferences folders may contain files that are not preference files—log files, lists of recently opened documents, and so on.

So, to locate the preference file for a given app, try each of these steps until you find it:

1. Open ~/Library/Preferences and set the window to List View (View → As List). Click the Name column to sort the list by name.

2. Scroll down to where the app’s name would be if it followed the reverse-domain name style. Look for adjacent files, too, in case the app has more than one.

3. Type a portion of the app’s name in the window’s Search field, or use the Find command (File → Find). If that yields no results, repeat with a portion of the developer’s name.

4. If you find more than one potential match, check the modification date. Usually the file or folder modified most recently is the one you’re looking for.

5. If you still haven’t found the file, repeat steps 1–4, but this time look in /Library/Preferences. Still no luck? Look in ~/Library/Containers/app name/Data/Library/Preferences, ~/Library/Application Support/app or developer name, or /Library/Application Support/app or developer name.

Note: Sometimes apps that have been updated over a period of years have older preference files in ~/Library/Preferences and newer ones in ~/Library/Containers/app name/Data/Library/Preferences. It’s best to check both places and look for the file with the more recent modification date.

Once you’ve located the file, then what? Well, you could drag it to the Trash, but I wouldn’t. If the file isn’t faulty after all, you may find yourself having to reset lots of preferences for no good reason. In some cases, that might mean digging out your license code and reentering your registration data. Instead, I suggest moving the file temporarily to your desktop. Follow these steps:

1. If the app is running, quit it.

2. Drag the preference file to your desktop.

3. Clear OS X’s system-wide preferences cache (so apps won’t continue to use the old values) in one of these ways:

§ Log out (choose Apple → Log Out username) and log back in.

§ Open Terminal (in /Applications/Utilities), type killall cfprefsd, and press Return.

4. Open the app again. It creates a new, default preference file for itself.

5. Test the app to see if the problem still exists. If not, the old preference file was probably at fault, so you can trash the one on your desktop. If the problem is still there, the preference file was probably good; you can quit the app and drag the file from your desktop back where it came from, replacing the preference file created in step 4. Having replaced the preference file, repeat step 3 to clear the cache again.

Reset NVRAM or SMC

Every Mac has at least two chips that store certain small bits of information even when the power is off. The ones we’re interested in here are NVRAM (non-volatile RAM) and SMC (system management controller). Although it’s uncommon, any of this memory can become corrupted, leading to various unpleasant symptoms:

· NVRAM: Incorrect NVRAM settings can lead to problems with startup (selecting the wrong startup disk, for example), audio, or screen resolution. To reset your NVRAM, shut down your Mac. While holding down ⌘-Option-P-R (which stands for “parameter RAM”), turn on your Mac. Keep holding the keys until you hear the second startup chime. Then release them and your Mac will continue booting normally.

· SMC: If the SMC settings are wrong, your Mac may have problems problems turning on, sleeping, or waking up; excessive fan noise; unusually slow system performance; video display issues; incorrect light settings (for status and battery lights, keyboard backlighting, and screen backlighting); or, for portables, not recognizing or charging a battery. Reset instructions vary from one Mac to the next; see Apple’s support page “Resetting the System Management Controller (SMC) on your Mac” at alt.cc/4b for details.

Use Activity Monitor

You may think that your Dock shows you all the apps that are currently running, but dozens or even hundreds of other background processes could be running too. Most of these are components of OS X that use system resources only when needed and stay out of the way the rest of the time. But sometimes a rogue program can start chewing up RAM or CPU cycles and not playing nice with others. If this happens, your whole Mac can slow down. To find out what’s happening behind the scenes, turn to Apple’s handy Activity Monitor, which you can find in /Applications/Utilities.

Activity Monitor can tell you all sorts of things about your CPU, RAM, disk, and network activity. But for troubleshooting purposes, I want to focus on just a couple of pieces of information.

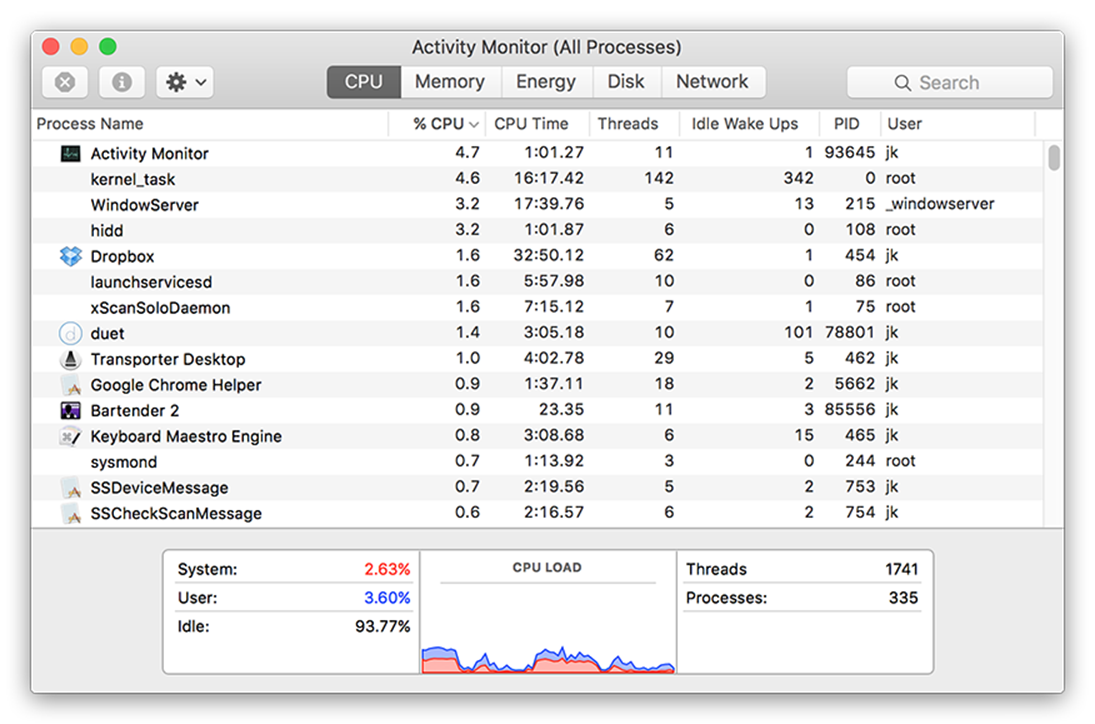

The default view in Activity Monitor (Figure 3) lists all your current processes. Click one of the toolbar buttons (CPU, Memory, Energy, Disk, or Network) to select a category of information to view.

Figure 3: Among the many things Activity Monitor can show is which apps (even ones not normally visible) are using the most CPU power, RAM, and other system resources.

Figure 3: Among the many things Activity Monitor can show is which apps (even ones not normally visible) are using the most CPU power, RAM, and other system resources.

The best place to start is the CPU category, which shows the amount of processor power being devoted to various processes. You can sort and filter what you see in Activity Monitor in various ways. I typically click the % CPU column header to display processes in order of their CPU usage. (When the arrow in the header points down, the most CPU-intensive tasks appear at the top; to change the sorting direction, click the header.)

To see which processes are using the most RAM, first click the Memory button on the toolbar. Then, look in the Memory column (again, you can sort in ascending or descending order) to see which processes are using up the most RAM at the moment.

I should warn you not to jump to hasty conclusions based on what you see in Activity Monitor. The fact that a process is using a lot of CPU power or RAM for a while isn’t necessarily a problem, but it can be useful for identifying certain issues. For example, if you notice that a background app you installed and then forgot about is being a CPU or RAM hog, consider checking for an update or uninstalling it.

You can quit processes from within Activity Monitor too. To do so, select a process and click the X ![]() button on the toolbar. Then click Quit. (If that doesn’t stop the process, repeat the procedure, but click Force Quit.) If you’re not the process’s owner, Activity Monitor prompts you to enter an administrator password.

button on the toolbar. Then click Quit. (If that doesn’t stop the process, repeat the procedure, but click Force Quit.) If you’re not the process’s owner, Activity Monitor prompts you to enter an administrator password.

Warning! Don’t quit processes that are owned by root (which could disable OS X, requiring a restart), and don’t quit the WindowServer process (which will log you out immediately). You can tell which user owns a process by looking in the User column. And be careful about quitting processes belonging to other logged-in users, as doing so could cause them to lose unsaved data.

I won’t say much about the other Activity Monitor categories, just a quick mention:

· Energy: If you’re using a laptop, this view’s Energy Impact column can help you figure out what’s using the most battery power.

· Disk: See the amount of data each process is writing to or reading from your disk.

· Network: See the amount of data each process is sending to (Sent Bytes) or receiving from (Rcvd Bytes) the internet.

Check Free Disk Space

OS X needs plenty of room on your startup volume for things like virtual memory swap files and software updates, and all sorts of bad things can happen if you have too little: kernel panics, crashes, hangs, slowdowns, and so on. My rule of thumb for adequate breathing room is to make sure your free disk space is at least 6 GB or twice the amount of RAM you have installed, whichever is larger. (Some people suggest leaving a certain percentage of your disk space, typically 10%, free, but this logic doesn’t scale well to very small or very large disks.) If necessary, delete unneeded files to free up extra space.

If you’re at a loss to know which files you can safely delete, allow me to offer some suggestions:

· Try any of several utilities that show you the size of each folder or file on your Mac, enabling you to quickly identify and delete large files you may not be aware of. For example:

§ DaisyDisk: daisydiskapp.com ($9.99)

§ Disk Inventory X: derlien.com (free)

§ GrandPerspective: grandperspectiv.sourceforge.net (free)

§ OmniDiskSweeper: alt.cc/1y (free)

§ WhatSize: whatsizemac.com ($29.99)

Although each of these utilities does things slightly differently (and I don’t have a favorite), GrandPerspective (Figure 4) is typical, giving you not only a graphical overview of file sizes but also a list of all folder sizes and an overview of space usage by file type.

Figure 4: When you can’t figure out where all those large files are on your disk, consult a utility such as GrandPerspective.

Figure 4: When you can’t figure out where all those large files are on your disk, consult a utility such as GrandPerspective.

· Finding, and deleting, duplicate copies of files on your disk can sometimes free up a good bit of space with no downside at all. To locate duplicate files, you can use WhatSize (mentioned just previously) or utilities such as these:

§ Chipmunk: furry-rodents.com ($17.95)

§ Gemini: alt.cc/1w ($9.99; also my personal favorite of these)

§ Tidy Up: alt.cc/4d ($29.99)

· Deleting caches is generally a safe choice, although it’s temporary and may slow down your Mac; see Clear Caches.

· Check your downloads folder(s) to see if they contain anything you no longer need, such as installers for software you’ve already installed, and drag those items to the Trash. By default, Safari uses ~/Downloads for downloads, but you can check Safari’s current location for downloads by going to Safari → Preferences → General and looking in the “File download location” pop-up menu. Other web browsers may have different downloads folders; check their preferences for locations if you’re unsure. Mail downloads are stored in~/Library/Containers/com.apple.mail/Data/Library/Mail Downloads.

· Your ~/Documents folder probably contains some files you no longer need. Skim the contents of this folder and its subfolders, looking for documents you have no further use for, and drag them to the Trash.

· Look in /Applications (and /Applications/Utilities) for any software that you’ve installed over the past year but never use. (Expired demo software, anyone?) While you’re at it, be sure to look through /Library, /Library/Application Support,~/Library, and ~/Library/Application Support for folder names matching the apps you just removed, and delete them as well. Resist the temptation to delete Apple software that came with OS X, though; you may need it later.

If you find it too cumbersome to uninstall software manually like this, or if you’re concerned that you might miss some pieces, try an uninstaller utility, such as one of the following:

§ AppBolish: alt.cc/sv ($9.00)

§ AppZapper: appzapper.com ($12.95)

§ CleanApp: alt.cc/sy ($14.99)

§ CleanMyMac: alt.cc/1v ($39.95; my favorite of these; see my TidBITS review at alt.cc/tba)

When you finish deleting files, don’t forget to empty your Trash (choose Finder → Empty Trash or press ⌘-Shift-Delete). Until you do so, your Mac won’t free up the disk space previously occupied by the files.

Check Log Files

Many of the apps on your Mac continually record details about what they’re doing in log files. In particular, they tend to make log entries when they encounter errors or other unexpected situations. In addition, every time an app crashes, a system-wide process called CrashReporter records the details of that crash in its own log. Log files are therefore an excellent source of information about what might be causing whatever problem you’re experiencing.

Log files tend to contain a lot of highly technical data that looks like gibberish to the uninitiated. This data is useful to programmers, though, and if you contact a company’s tech support department to report a bug, they may ask you to send them one of your log files to help determine what the problem was. However, even without understanding all the ins and outs of an app’s workings, taking a quick glance at its log files can sometimes give you hints that will help you track down a problem.

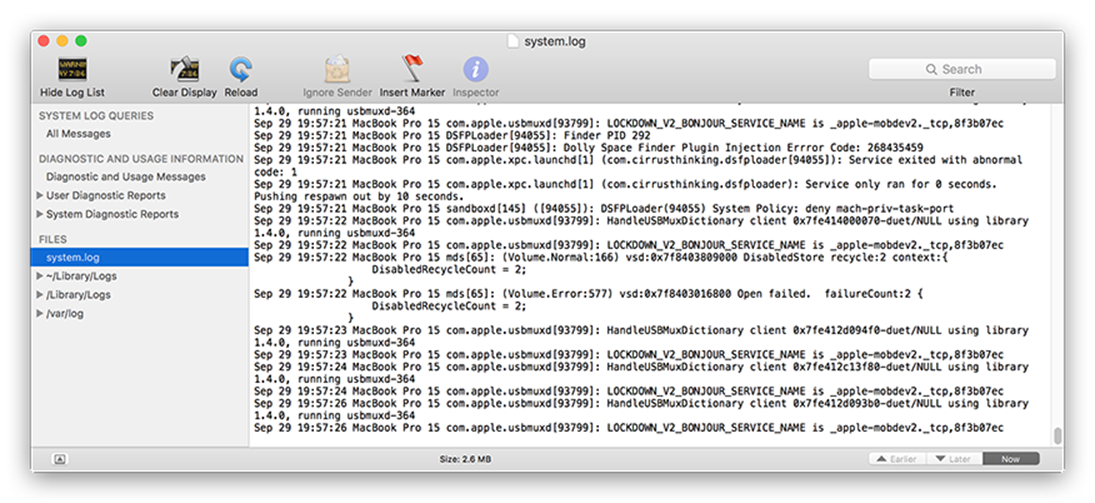

The easiest way to view log files is with an app in /Applications/Utilities called Console. (It could just as easily be called Log Viewer; all it does is display logs.) When you open it, it displays one or more windows like the one shown in Figure 5. On the left, the window lists logs you can view; if this list isn’t showing, click the Show Log List button on the toolbar.

Figure 5: It’s not pretty, but Console can help you figure out why something went wrong by showing log files that apps create.

Figure 5: It’s not pretty, but Console can help you figure out why something went wrong by showing log files that apps create.

One particularly important log file that Console can show is called system.log, which tends to contain the most useful error messages generated by apps and OS X itself, going back to your last restart. (You may also have one or more older versions available; look in the log list under /var/log for files like system.log.0.bz2, where the number after log increases with older logs.) To display the contents of system.log, select it in the list on the left.

So you’ve opened this log, and now you’re thinking: “I don’t have a clue what I’m looking at or how to find what I’m looking for.” It may take some time and experience to get a feel for what’s truly helpful and what to do when you find it, but here are some tips to help you glean useful information from a log:

· Start at the end. The most recent information is at the bottom, and it’s updated in real time. If you’ve just experienced a crash or other problem, information about it is likely to be near the bottom of one of the logs.

· Filter. You can filter a log to display only the lines containing some string of text by typing in the Filter field on the toolbar. For example, if you type error, Console displays only those lines with the word error in them somewhere. (That is, in fact, a highly useful place to start. Another useful term to filter for is fail. You can also search for the name of the misbehaving app.)

· Repetition is significant. Repetition is significant. Pay special attention to lines that repeat many times. If you see the same error message (or similar messages) 50 times in a row, you know that an app is repeatedly trying and failing at some task. At the same time, some apps are simply chatty and fill logs with lots of messages that don’t indicate any problems.

· Consult the oracle. If you see a phrase that suggests a problem but you don’t know what it means, try searching for it in Google (or your favorite search engine), enclosed in quotation marks. For example, suppose you have a log entry that reads:

Apr 25 19:19:03 MacBook-Pro /Library/PreferencePanes/BusySync.prefPane/Contents/Resources/BusySync.app/Contents/MacOS/BusySync[411]: Warning: accessing obsolete X509Anchors.

You might try searching the web for "Warning: accessing obsolete X509Anchors" (again, remember the quotation marks), which may list developer documentation on what that phrase means or reports from other people who have seen that message in their logs and have theories as to its significance.

· Go back further. You can also look at older copies of system.log by navigating in the log list to /var/log.

· Cast a wider net. Although system.log is the most useful log file, it doesn’t contain every log entry. Also look in other places in the Log list, such as /Library/Logs and ~/Library/Logs, for logs specific to an app (app-specific logs usually have the app’s name, or at least the developer’s name, in the log title). In addition, check in /Library/Logs/CrashReporter and ~/Library/Logs/CrashReporter for an app’s crash logs.

Clear Caches

Caches help apps load more quickly and run more efficiently by storing frequently used information. Usually, caches speed up your Mac and are therefore good to keep around. However, in certain situations, a cache can cause problems rather than solving them. If a cache file becomes damaged, for example, an app may crash or otherwise misbehave when it reads that file. Or, if a cache file grows excessively large, it may take longer to read it than it did to generate it in the first place.

Most of your caches live in one of three places: /Library/Caches, ~/Library/Caches, or ~/Library/Containers/app name/Data/Library/Caches/app name (where both instances of app name follow the reverse-domain name style I explained in Check Preference Files). Any of these cache files can be deleted safely, because apps regenerate cache files automatically as needed. However, I recommend against wiping out caches indiscriminately, because intact caches (which will be most of them) do improve your Mac’s performance, and deleting them means that your Mac will have to recreate them.

When a troubleshooting procedure calls for clearing caches, follow these steps:

1. Quit the app you’re troubleshooting, if it’s running.

2. Look for a file or folder containing the name of the offending app. Look first in ~/Library/Caches and then in /Library/Caches and ~/Library/Containers/app name/Data/Library/Caches/app name. If you find it, drag it to the Trash. (In some cases, you may have to enter your administrator password when dragging cached files to the Trash.) Reopen the app and see if the problem still exists. If not, you’re done.

3. If you’re having trouble with an app that’s part of Microsoft Office 2004, 2008, or 2011, consider deleting its font cache, which is stored separately from other caches. (This procedure does not apply to Office 2016.) To do so, quit all your Office apps, navigate to~/Library/Preferences/Microsoft, and drag the appropriate file to the Trash:

§ Office 2004: Office Font Cache (11)

§ Office 2008: Office 2008/Office Font Cache (12)

§ Office 2011: Office 2011/Office Font Cache

Test to see if the problem has disappeared.

4. OS X maintains a system-level font cache that numerous apps use. Bad font cache files have been implicated in many problems. To delete most of your font caches manually, you can open Terminal (in /Applications/Utilities) and type this, followed by Return:

atsutil databases -remove

Then restart your Mac, empty your Trash, and see if the problem still exists. However, be aware that after you delete these font caches, any fonts you’ve disabled in Font Book will be re-enabled.

5. Delete your other system-wide caches—that is, everything else in /Library/Caches—and restart your Mac. Test once again to see if the problem is gone.

6. As a last resort, delete the caches in /System/Library/Caches. (You’ll need to enter your administrator password to do so.) Restart your Mac.

Cache-Clearing Utilities

Because dragging a folder to the Trash is easy and lets me control exactly what gets deleted, I prefer to clear my caches manually. However, numerous utilities, including the following, let you clear caches with just a couple of clicks (usually letting you choose which caches, and also letting you delete logs and other clutter):

· CleanMyMac: alt.cc/1v ($39.95)

· Cocktail: alt.cc/2i ($19)

· El Capitan Cache Cleaner: alt.cc/2q ($9.99)

· MacCleanse: alt.cc/2r ($29.95)

· OnyX: titanium.free.fr (free)

Check Your RAM

OS X is picky about the quality of RAM in your Mac. If RAM is defective or even slightly out of spec, kernel panics or other crashes can result. RAM installed by Apple at the factory has a low incidence of failure, but if you’ve installed third-party RAM yourself (and especially if you used a cheaper brand), you’re at a greater risk for problems.

Several utilities can check your RAM to make sure it’s healthy:

· Apple Hardware Test or Apple Diagnostics: These tools are not only free, one of them also came with your Mac (or can be run over the internet). Newer Macs include Apple Diagnostics, while older ones come with Apple Hardware Test. (Read on for instructions on how to use these.)

· Memtest OS X: memtestosx.org, free (command-line version)

· Rember: alt.cc/2j, free (a GUI utility based on Memtest OS X)

· Techtool Pro: alt.cc/27, $99.99

If you use a third-party tool, follow the instructions that came with it.

To run Apple Hardware Test or Apple Diagnostics, follow these steps:

1. If you have a disc or USB drive with Apple Hardware Test on it, insert it into your Mac. If your Mac shipped after Lion was released and did not include external boot media, make sure the Mac is connected to the internet (via Ethernet) or that a Wi-Fi network connection is available.

2. Choose Apple → Shut Down and wait for your Mac to shut down completely.

3. Press the power button to turn on your Mac, and immediately press and hold the D key until the Apple Hardware Test chooser screen appears or Apple Diagnostics starts, either of which may take a minute or more. If Apple Hardware Test or Apple Diagnostics can’t be found on any local media and you’re using a Wi-Fi connection, select a wireless network when prompted, and enter its password (if any).

4. Select a language (using the mouse or the arrow keys) and click the right arrow button or press Return. (For Apple Diagnostics, you only need to do this the first time you run it.)

5. For Apple Hardware Test:

a. On the Hardware Tests tab, if there’s an Extended Test button, click it. If not, select the checkbox “Perform extended testing (takes considerably more time)” and click Test.

b. Kick back with a good book while you wait for the test to complete. The screen may say something like “Estimated time: 10–15 minutes, or longer depending on the amount of memory installed.” If your machine has lots of RAM, “or longer” could turn out to be hours.

c. If the test uncovers no problems, the Test Results area either displays “No trouble found” or puts the word “Passed” next to all the applicable tests. If a problem does exist, a failure message appears along with advice for what to do next.

For Apple Diagnostics:

§ The test runs automatically, taking just 2–3 minutes. At the end, it either says “No issues found” or lists any problems along with information on what you should do about them.

Note: Sometimes Apple Hardware Test or Apple Diagnostics may show an error code in lieu of an explanation. Your best bet is to type that code into your favorite search engine. For example, I once had a code that meant the fan that cools my iMac’s hard drive was failing. After I replaced that fan, the error code went away.

6. Click Restart to restart your Mac.

If Apple Hardware Test, Apple Diagnostics, or another utility reports that you have defective RAM, the module in question must be replaced. If the module was installed by Apple and your Mac is still under warranty (or AppleCare), Apple should replace it at no charge. If you purchased your RAM from another vendor, check their warranty terms. (Several RAM vendors offer lifetime warranties.)

Note: Even if your RAM passes all tests perfectly, it could be out of spec enough to cause problems. I mention an example ahead in Your Mac Keeps Turning Itself Off.

Test for Reproducibility

You’ve heard the joke: “I said, ‘Doctor, it hurts when I do this.’ And the doctor said, ‘Then don’t do that.’” But, of course, any doctor truly would want to know what makes a symptom worse (or better). If you can clearly describe the circumstances under which some problem reliably occurs, you’ll be that much closer to a diagnosis. It’s not terribly helpful to know that your arm hurts “sometimes” or that Safari crashes “now and then.” But if your arm hurts only when you hold it at a certain angle or Safari crashes only when you visit a certain website, then you’re on to something.

Programmers love detailed reports about exactly how to reproduce a problem. If the programmers can get the problem to occur, they can usually fix it. If they can’t, they have to guess at the cause. If you report a bug to a software developer, giving information on reproducibility is important. But even if you’re just trying to work around it yourself, knowing where and when the problem occurs can help.

Testing for reproducibility isn’t as easy as it sounds, though, because sometimes problems seem to occur randomly or unpredictably. But you can get at least partway there with these suggestions:

· Take notes. When you encounter a problem, think about the two or three things you did most recently, and write them down. For example, if Mail crashes, you might make a note of the fact that you just checked your email, and before that you added a new rule, and before that you did a search for messages from your boss. If the problem happens repeatedly, these notes can help you find patterns.

· Narrow the scope. Let’s say a problem occurs when you have a dozen apps running. Try quitting half of them and see if the problem still occurs. If it does, quit half of the ones remaining, and so on; if it doesn’t, quit the ones currently running and relaunch the other half. Or, if a problem happens when you’re running OS X normally, try a safe boot (see Start Up in Safe Mode). If the problem goes away, you’ll know it was caused by some process that loads during startup or login.

You’re trying to get the problem to occur under conditions as specific and repeatable as possible. To that end, it’s most helpful to change only one type of thing at a time. For example, if your Mac is doing something odd and you quit apps, reset your SMC, add RAM, and repair your disk before confirming that the problem has gone away, you’ll be unable to tell which of those procedures fixed it—and that can be quite important to know, especially if the problem happens again in the future.

· Try other environments. If a problem occurs on your Mac, does it also happen on your spouse’s Mac? If your mouse is jittery when plugged into your keyboard’s USB port, is it also jittery when plugged directly into the Mac’s USB port? If a document looks weird in TextEdit, does it also look weird in Word? Try to test whether your problem appears under a variety of circumstances.

If you can reach the point where you can make a problem occur intentionally—always and only when you’re trying to reproduce it—you’re close to a solution. If the obvious remedies (such as disabling preference files, deleting caches, and starting up in safe mode) don’t work, you at least have solid information to provide to the developer’s tech support staff, which can help them solve your problem.

Get System Information

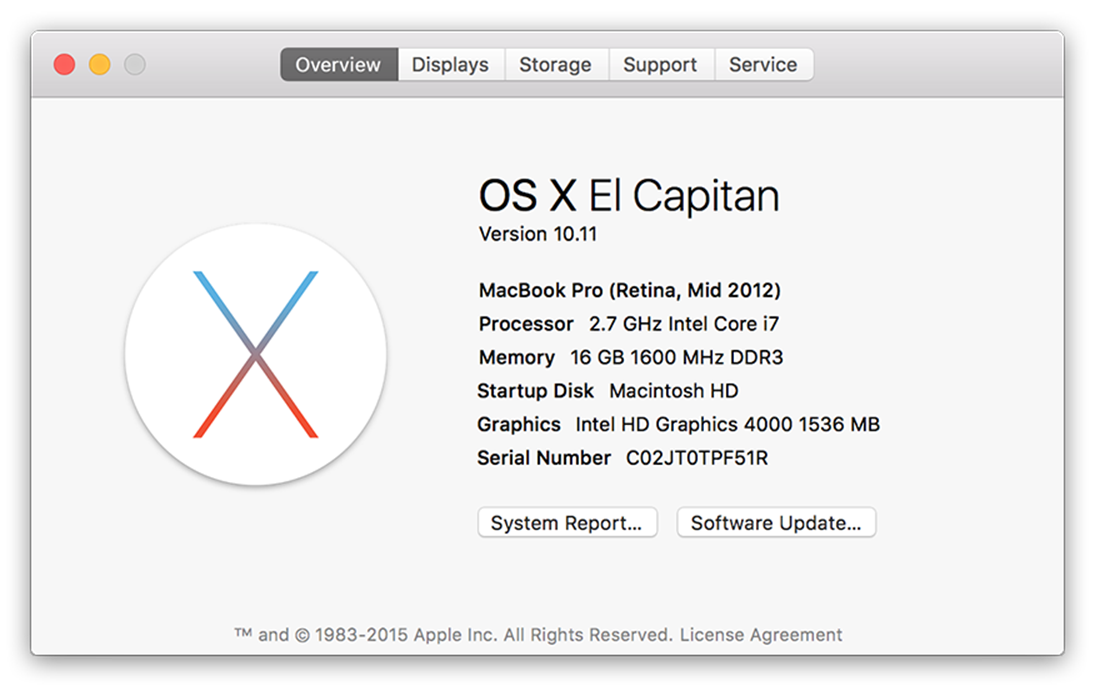

Many of the troubleshooting steps you may take (such as searching for information on Apple’s website or contacting tech support) require that you know exactly which version of OS X you’re running, among other details. If you don’t know which version of OS X is installed, choose Apple → About This Mac (Figure 6).

Figure 6: Choose Apple → About This Mac to display a window showing your Mac model, operating system version, and more. The window’s appearance varies by operating system version.

Figure 6: Choose Apple → About This Mac to display a window showing your Mac model, operating system version, and more. The window’s appearance varies by operating system version.

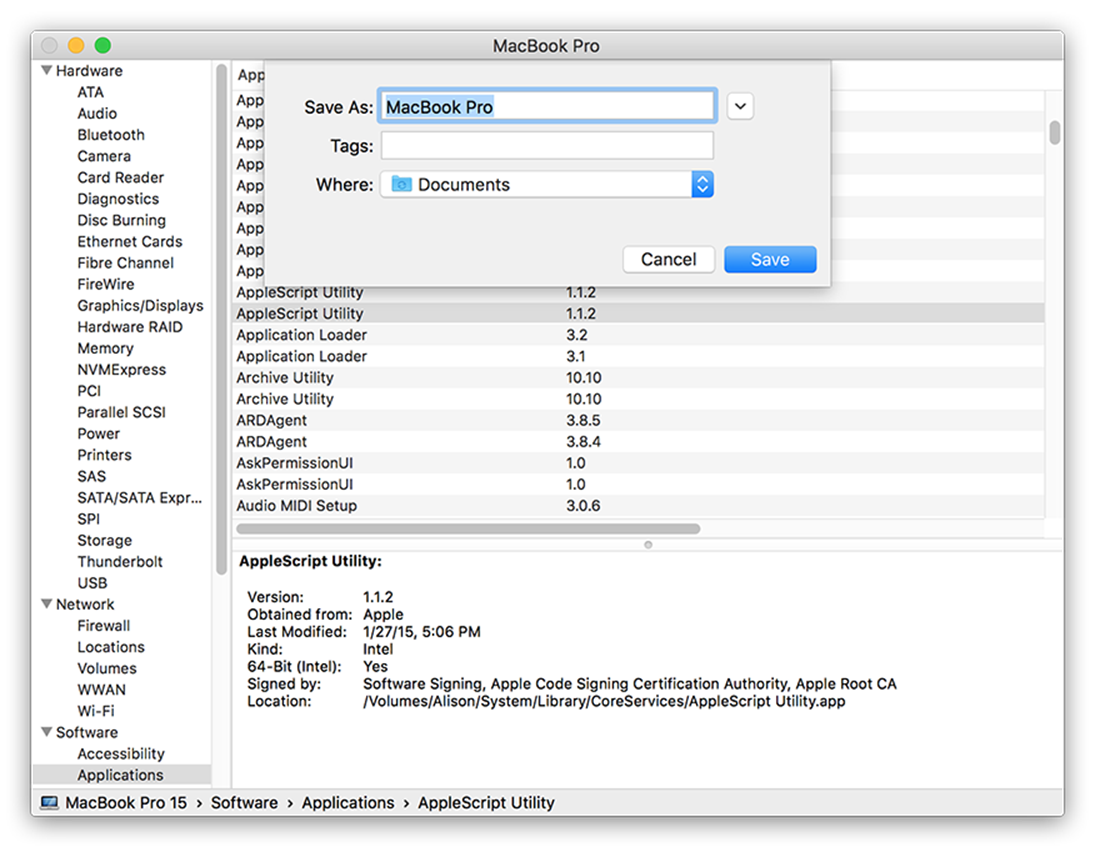

When you’re talking to a developer’s tech support staff, they may ask you for more detailed information about your Mac, such as which third-party software is installed and what brand of hard drive it has. To get this information, use an Apple utility called System Information. You can open this utility by clicking System Report (or, in older versions of OS X, More Info) in the About This Mac window or by double-clicking System Information in /Applications/Utilities.

At this point, a technician may ask you to look for, and read off, certain information found in the app’s main window, or to save a file with all the details and send it in as an email attachment. To do this, choose File → Save, type a name, and choose a location, as shown in Figure 7. Click the Save button, and then attach the saved file to an email message.

Figure 7: You can save the entire System Information report about your Mac to send to a tech support representative.

Figure 7: You can save the entire System Information report about your Mac to send to a tech support representative.