Introduction to Game Design, Prototyping, and Development (2015)

Part I: Game Design and Paper Prototyping

Chapter 4. The Inscribed Layer

This is the first of three chapters that explore the layers of the Layered Tetrad in greater depth.

As you learned in Chapter 3, “The Layered Tetrad,” the inscribed layer covers all elements that are directly designed and encoded by game developers.

In this chapter, we look at the inscribed aspects of all four elements: mechanics, aesthetics, narrative, and technology.

Inscribed Mechanics

The inscribed mechanics are most of what one would think of as the traditional job of the game designer. In board games, this includes designing the board layout, the rules, the various cards that might be used and any tables that could be consulted. Much of the inscribed mechanics are described very well in Tracy Fullerton’s book Game Design Workshop in her chapter on formal elements of games, and for the sake of lexical solidarity (and my distaste for every game design book using different terminology), I reuse her terminology throughout this section of the chapter as much as the Layered Tetrad framework allows.

As mentioned in Chapter 2, “Game Analysis Frameworks,” Tracy Fullerton lists seven formal elements of games in her book: player interaction patterns, objectives, rules, procedures, resources, boundaries, and outcomes. In the formal, dramatic, and dynamic elements framework, these seven formal elements are defined as the things that make games different from other media.

Inscribed mechanics are a bit different from this, although there is a lot of overlap because mechanics is the element of the tetrad that is unique to games. However, the core of the inscribed layer is that everything in it is intentionally designed by a game developer, and the mechanics are no exception. As a result of this, inscribed mechanics does not include procedures or outcomes (although they are part of Fullerton’s formal elements) because both are controlled by the player and therefore part of the dynamic layer. We’ll also add a couple of new elements to give us the following list of inscribed mechanical elements:

![]() Objectives: Objectives cover the goals of the players in the game. What are the players trying to accomplish?

Objectives: Objectives cover the goals of the players in the game. What are the players trying to accomplish?

![]() Player relationships: Player relationships define the ways that players combat and collaborate with each other. How do the players’ objectives intersect, and does this cause them to collaborate or compete?

Player relationships: Player relationships define the ways that players combat and collaborate with each other. How do the players’ objectives intersect, and does this cause them to collaborate or compete?

![]() Rules: Rules specify and limit player actions. What can and can’t the players do to achieve their objective?

Rules: Rules specify and limit player actions. What can and can’t the players do to achieve their objective?

![]() Boundaries: Boundaries define the limits of the game and relate directly to the magic circle. Where are the edges of the game? Where does the magic circle exist?

Boundaries: Boundaries define the limits of the game and relate directly to the magic circle. Where are the edges of the game? Where does the magic circle exist?

![]() Resources: Resources include assets or values that are relevant within the boundaries of the game. What does the player own in-game that enables her in-game actions?

Resources: Resources include assets or values that are relevant within the boundaries of the game. What does the player own in-game that enables her in-game actions?

![]() Spaces: Spaces define the shape of the game space and the possibilities for interaction therein. This is most obvious in board games, where the board itself is the space of the game.

Spaces: Spaces define the shape of the game space and the possibilities for interaction therein. This is most obvious in board games, where the board itself is the space of the game.

![]() Tables: Tables define the statistical shape of the game. How do players level up as they grow in power? What moves are available to a player at a given time?

Tables: Tables define the statistical shape of the game. How do players level up as they grow in power? What moves are available to a player at a given time?

All of these inscribed mechanical elements interact with each other, and overlap certainly exists between them (e.g., the tech tree in Civilization is a table that is navigated like a space). The purpose of dividing them into these seven categories is to help you as a designer think about the various possibilities for design in your game. Not all games have all elements, but as with the “lenses” in Jesse Schell’s book The Art of Game Design: A Book of Lenses, these inscribed mechanical elements are seven different ways to look at the various things that you can design for a game.

Objectives

While many games have an apparently simple objective—to win the game—in truth, every player will be constantly weighing several objectives every moment of your game. These can be categorized based on their immediacy and their import to the player, and some objectives may be considered very important to one player while being less important to another.

Immediacy of Objectives

As shown in the image in Figure 4.1 from the beautiful game Journey by thatgamecompany, nearly every screen of a modern game presents the player with short-, mid-, and long-term objectives.

Figure 4.1 Short-, mid-, and long-term objectives in the first level of Journey with objectives highlighted green, blue, and purple respectively

In the short term, the player wishes to charge her scarf (which enables flying in Journey), so she’s shouting (the white sphere around her), which draws the highlighted scarf pieces to her. She also is drawn to explore the nearby building. For mid-term goals, there are three additional structures near the horizon. Because the rest of the desert is largely barren, the player is attracted to the ruins on the horizon (this indirect guidance strategy is used several times throughout Journey and is analyzed in Chapter 13, “Guiding the Player”). And, for long-term goals, the player is shown the mountain with the shaft of light (in the top-left corner of Figure 4.1) in the first few minutes of the game, and it is her long-term goal throughout the game to reach the top of this mountain.

Importance of Objectives

Just as objectives vary in immediacy, they also vary in importance to the player. In an open-world game like Skyrim by Bethesda Game Studios, there are both primary and optional objectives. Some players may choose to exclusively seek the primary objectives and can play through Skyrim in as little as 10 to 20 hours, whereas others who wish to explore various side quests and optional objectives can spend more than 400 hours in the game without exhausting the content (and even without finishing the primary objectives). Optional objectives are often tied to specific types of gameplay; in Skyrim, there is a whole series of missions for players who wish to join the Thieves Guild and specialize in stealth and theft. There are also other series of missions for those who wish to focus on archery or melee1 combat. This ensures that the game could adapt to the varying gameplay styles of different players.

1 This is a word that is often mispronounced by gamers. The word melee is pronounced “may-lay.” The word “mealy” (pronounced “mee-lee”) means either pale or in some other way like grain meal (e.g., cornmeal).

Conflicting Objectives

As a player, the objectives that you have will often conflict with each other or compete for the same resources. In a game like Monopoly, the overall objective of the game is to finish the game with the most money, but you must give up money to purchase assets like property, houses, and hotels that will eventually make you more money later. Looking at the design goal of presenting the player with interesting choices, a lot of the most interesting choices that a player can make are those that will benefit one objective while hurting another.

Approaching it from a more pragmatic perspective, each objective in the game will take time to complete, and a player may only have a certain amount of time that she is willing to devote to the game. Returning to the Skyrim example, many people (myself included) never finished the main quest of Skyrim because they spent all of their time playing the side quests and lost track of the urgency of the main story. Presumably, the goal of Skyrim’s designers was to allow each player to form her own story as she played through the game, and it’s possible that the designers wouldn’t care that I hadn’t finished the main quest as long as I enjoyed playing the game, but as a player, I felt that the game ended not with a bang but a whimper as the layers upon layers of quests I was given had seemingly smaller and smaller returns. If, as a designer, it’s important to you that your players complete the main quest of the game, you need to make sure that the player is constantly reminded of the urgency of the task and (unlike many open world games) you may need to have consequences for the player if she does not complete the main quest in a timely manner. As an example, in the classic game Star Control, if the player did not save a certain alien species within a given amount of time from the start of the game, the species’ planet actually disappeared from the universe.

Player Relationships

Just as an individual player has several objectives in mind at any given time, the objectives that players have also determine relationships between them.

Player Interaction Patterns

In Game Design Workshop, Fullerton lists seven different player interaction patterns:

![]() Single player versus game: The player has the objective of beating the game.

Single player versus game: The player has the objective of beating the game.

![]() Multiple individual players versus game: Several co-located players each have the objective of beating the game, but they have little or no interaction with each other. This can often be seen in MMORPGs (massively multiplayer online roleplaying games) like World of Warcraftwhen players are each seeking to succeed at their missions in the same game world but not interacting with each other.

Multiple individual players versus game: Several co-located players each have the objective of beating the game, but they have little or no interaction with each other. This can often be seen in MMORPGs (massively multiplayer online roleplaying games) like World of Warcraftwhen players are each seeking to succeed at their missions in the same game world but not interacting with each other.

![]() Cooperative play: Multiple players share the common objective of beating the game together.

Cooperative play: Multiple players share the common objective of beating the game together.

![]() Player versus player: Each of two players has the objective of defeating the other.

Player versus player: Each of two players has the objective of defeating the other.

![]() Multilateral competition: The same as player versus player, except that there are more than two players, and each player is trying to beat all of the others.

Multilateral competition: The same as player versus player, except that there are more than two players, and each player is trying to beat all of the others.

![]() Unilateral competition: One player versus a team of other players. This can be seen in the board game Scotland Yard (also called Mr. X), where one player plays a criminal trying to evade the police and the other 2 to 4 players of the game are police officers trying to collaborate to catch the criminal.

Unilateral competition: One player versus a team of other players. This can be seen in the board game Scotland Yard (also called Mr. X), where one player plays a criminal trying to evade the police and the other 2 to 4 players of the game are police officers trying to collaborate to catch the criminal.

![]() Team competition: Two teams of players, each with the objective of beating the other.

Team competition: Two teams of players, each with the objective of beating the other.

Some games, like Mass Effect by BioWare, provide computer-controlled allies for the player. In terms of designing player interaction patterns, these computer-controlled allies can either be thought of as an element of the single player’s abilities in the game or as proxies for other players that could play the game, so a single-player game with computer-controlled allies could be seen either as single player versus game or as cooperative play.

Player Relationships and Roles Are Defined by Objectives

In addition to the interaction patterns listed in the preceding section, there are also various combinations of them, and in several games, one player might be another player’s ally at one point and their competitor at another. For example, when trading money for property in a game likeMonopoly, two players make a brief alliance with each other, even though the game is primarily multilateral competition.

At any time, the relationship between each player and both the game and other players is defined by the combination of all the players’ layered objectives. These relationships lead each player to play one of several different roles:

![]() Protagonist: The protagonist role is that of the player trying to conquer the game.

Protagonist: The protagonist role is that of the player trying to conquer the game.

![]() Competitor: The player trying to conquer other players. This can be either to win the game or on behalf of the game (e.g., in the 2004 board game Betrayal at House on the Hill, partway through the game, one of the players is turned evil and then must try to kill the other players).

Competitor: The player trying to conquer other players. This can be either to win the game or on behalf of the game (e.g., in the 2004 board game Betrayal at House on the Hill, partway through the game, one of the players is turned evil and then must try to kill the other players).

![]() Collaborator: The player working to aid other players.

Collaborator: The player working to aid other players.

![]() Citizen: The player in the same world as other players but not really collaborating or competing with them.

Citizen: The player in the same world as other players but not really collaborating or competing with them.

In many multiplayer games, all players will play each of these roles at different times, and as you’ll see when we look into the dynamic layer, there are different types of players who prefer different roles.

Rules

Rules limit the players’ actions. Rules are also the most direct inscription of the designer’s concept of how the game should be played. In the written rules of a board game, the designer is attempting to inscribe and encode the experience that she wants for the players to have when they play the game. Later, the players decode these rules and hopefully experience something like what the designer intended.

Unlike paper games, digital games usually have very few inscribed rules that are read directly by the player; however, the programming code written by the game developers is another way of encoding rules that will be decoded through play. Because rules are the most direct method through which the game designer communicates with the player, rules act to define many of the other elements. The money in Monopoly only has value because the rules declare that it can be used to buy assets and other resources.

Explicitly written rules are the most obvious form of rules, but there are also implicit rules. For example, when playing poker, there is an implicit rule that you shouldn’t hide cards up your sleeve. This is not explicitly stated in the rules of poker, but every player understands that doing so would be cheating.2

2 This is a good example of one of the differences between single-player and multiplayer game design. In a multiplayer poker game, concealing a card would be cheating and could ruin the game. However, in the game Red Dead Redemption by Rockstar Studios, the in-game poker tournaments become much more interesting and entertaining once the player acquires the suit of clothes that allows her character to conceal and swap poker cards at will (with a risk of being discovered by NPCs).

Boundaries

Boundaries define the edges of the space and time in which the game takes place. Within the boundaries, the rules and other aspects of the game apply: poker chips are worth something, it’s okay to slam into other hockey players on the ice, and it matters which car crosses a line on the ground first. Sometimes, boundaries are physical, like the wall around a hockey rink. Other times, boundaries are less obvious. When a player is playing an ARG (alternate reality game), the game is often surrounding the player during her normal day. As mentioned in Chapter 1, “Thinking Like a Designer,” players of Majestic gave Electronic Arts their phone number, fax number, email address, and home address; and they would receive phone calls, faxes, and so on at all times of the day from characters in the game. The intent of the game was to blur the boundaries between gaming and everyday life.

Resources

Resources are things of value in a game. These can be either things like assets or nonmaterial attributes. Assets in games include things such as the equipment that Link has collected in a Legend of Zelda game; the resource cards that players earn in the board game Settlers of Catan; and the houses, hotels, and property deeds that players purchase in Monopoly. Attributes often include things such as health, amount of air left when swimming under water, and experience points. Because money is so versatile and so ubiquitous, it is somewhere between the two. A game can have physical money assets (like the cash in Monopoly), or it can have a nonphysical money attribute (like the amount of money that a player has in Grand Theft Auto).

Spaces

Designers are often tasked with creating navigable spaces. This includes both designing the board for a board game and designing virtual levels in a digital game. In both cases, you want to think about both flow through the space and making the areas of the space unique and interesting. Things to keep in mind when designing spaces include the following:

![]() The purpose of the space: Architect Christopher Alexander spent years researching why some spaces were particularly well suited to their use and why others weren’t. He distilled this knowledge into the concept of design patterns through his book A Pattern Language,3 which explored various patterns for good architectural spaces. The purpose of the book was to put forward a series of patterns that others could use to make a space that correctly matched the use for which it was intended.

The purpose of the space: Architect Christopher Alexander spent years researching why some spaces were particularly well suited to their use and why others weren’t. He distilled this knowledge into the concept of design patterns through his book A Pattern Language,3 which explored various patterns for good architectural spaces. The purpose of the book was to put forward a series of patterns that others could use to make a space that correctly matched the use for which it was intended.

3 Christopher Alexander, Sara Ishikawa, and Murray Silverstein, A Pattern Language: Towns, Buildings, Construction (New York: Oxford University Press, 1977).

![]() Flow: Does your space allow the player to move through it easily, or if it does restrict movement, is there a good reason? In the board game Clue, players roll a single die each turn to determine how far they can move. This can make it very slow to move about the game-board. (The game board is 24×25 spaces, so with an average roll of 3.5, it could take 7 turns to cross the board.) Realizing this, the designers added secret passages that allow players to teleport from each corner of the board to the opposite corner, which helped flow through the mansion quite a bit.

Flow: Does your space allow the player to move through it easily, or if it does restrict movement, is there a good reason? In the board game Clue, players roll a single die each turn to determine how far they can move. This can make it very slow to move about the game-board. (The game board is 24×25 spaces, so with an average roll of 3.5, it could take 7 turns to cross the board.) Realizing this, the designers added secret passages that allow players to teleport from each corner of the board to the opposite corner, which helped flow through the mansion quite a bit.

![]() Landmarks: It is more difficult for players to create a mental map of 3D virtual spaces than actual spaces through which they have walked in real life. Because of this, it is important that you have landmarks in your virtual spaces that players can use to more easily orient themselves. In Honolulu, Hawaii, people don’t give directions in terms of compass directions (north, south, east, and west) because these are not terribly obvious unless it’s sunrise or sunset. Instead, the people of Honolulu navigate by obvious landmarks: mauka (the mountains to the northeast),makai (the ocean to the southwest), Diamond Head (the landmark mountain to the southeast), and Ewa (the area to the northwest). On other parts of the Hawaiian Islands, mauka means inland and makai means towards the ocean, regardless of compass direction (the islands being circular). Making landmarks that players can easily see will limit the number of times your players need to consult the map to figure out where they are.

Landmarks: It is more difficult for players to create a mental map of 3D virtual spaces than actual spaces through which they have walked in real life. Because of this, it is important that you have landmarks in your virtual spaces that players can use to more easily orient themselves. In Honolulu, Hawaii, people don’t give directions in terms of compass directions (north, south, east, and west) because these are not terribly obvious unless it’s sunrise or sunset. Instead, the people of Honolulu navigate by obvious landmarks: mauka (the mountains to the northeast),makai (the ocean to the southwest), Diamond Head (the landmark mountain to the southeast), and Ewa (the area to the northwest). On other parts of the Hawaiian Islands, mauka means inland and makai means towards the ocean, regardless of compass direction (the islands being circular). Making landmarks that players can easily see will limit the number of times your players need to consult the map to figure out where they are.

![]() Experiences: The game as a whole is an experience, but the map or space of the game also needs to be sprinkled with interesting experiences for your players. In Assassin’s Creed 4: Black Flag, the world map is a vastly shrunken version of the Caribbean Sea. Even though the actual Caribbean has many miles of empty ocean between islands that would take a sailing vessel hours or days to cross, the Caribbean of AC4 has events sprinkled throughout it that ensure that the player will encounter a chance to have an experience several times each minute. These could be small experiences like finding a single treasure chest on a tiny atoll, or they could be large experiences like coming across a fleet of enemy ships.

Experiences: The game as a whole is an experience, but the map or space of the game also needs to be sprinkled with interesting experiences for your players. In Assassin’s Creed 4: Black Flag, the world map is a vastly shrunken version of the Caribbean Sea. Even though the actual Caribbean has many miles of empty ocean between islands that would take a sailing vessel hours or days to cross, the Caribbean of AC4 has events sprinkled throughout it that ensure that the player will encounter a chance to have an experience several times each minute. These could be small experiences like finding a single treasure chest on a tiny atoll, or they could be large experiences like coming across a fleet of enemy ships.

![]() Short-, medium-, and long-term objectives: As demonstrated in the shot from Journey, shown in Figure 4.1, your space can have multiple levels of goals. In open-world games, a player is often shown a high-level enemy early on so that she has something to aspire to defeat later in the game. Many games also clearly mark areas of the map as easy, medium, or high difficulty.

Short-, medium-, and long-term objectives: As demonstrated in the shot from Journey, shown in Figure 4.1, your space can have multiple levels of goals. In open-world games, a player is often shown a high-level enemy early on so that she has something to aspire to defeat later in the game. Many games also clearly mark areas of the map as easy, medium, or high difficulty.

Tables

Tables are a critical part of game balance, particularly when designing modern digital games. Put simply, tables are grids of data that are often synonymous with spreadsheets, but there are many different things that tables can be used to design and illustrate:

![]() Probability: Tables can be used to determine probability in very specific situations. In the board game Tales of the Arabian Nights, the player selects the proper table for the individual creature she has encountered, and it gives her a list of possible reactions that she can have to that encounter and the various results of each of her possible reactions.

Probability: Tables can be used to determine probability in very specific situations. In the board game Tales of the Arabian Nights, the player selects the proper table for the individual creature she has encountered, and it gives her a list of possible reactions that she can have to that encounter and the various results of each of her possible reactions.

![]() Progression: In paper roleplaying games (RPGs) like Dungeons & Dragons, tables show how the players’ abilities increase and change as the player character’s level increases.

Progression: In paper roleplaying games (RPGs) like Dungeons & Dragons, tables show how the players’ abilities increase and change as the player character’s level increases.

![]() Playtest Data: In addition to tables that players use to enable the game, you as a designer will also create tables to hold playtest data and information about player experiences.

Playtest Data: In addition to tables that players use to enable the game, you as a designer will also create tables to hold playtest data and information about player experiences.

Of course, tables are also a form of technology in games, so they cross the line between mechanics and technology. Tables as technology include the storage of information and any transformation of information that can happen in the table (e.g., formulae in spreadsheets). Tables as mechanics include the design decisions that game designers make and inscribe into the table.

Inscribed Aesthetics

Inscribed aesthetics are those aesthetic elements that are crafted by the developers of the game. These cover all the five senses, and as a designer, you should be aware that throughout the time that your player is playing the game, she will be sensing with all five of her senses.

The Five Aesthetic Senses

Designers must consider all five of the aesthetic senses when inscribing games. These five senses are:

![]() Vision: Of the five senses, vision is the one that gets the most attention from most game development teams. As a result, the fidelity of the visual experience that we can deliver to players has seen more obvious improvement over the past several years than that of any other sense. When thinking about the visible elements of your game, be sure to think beyond the 3D art in the game or the art of the board in a paper game. Realize that everything that players (or potential players) see that has anything to do with your game will affect their impression of it as well as their enjoyment of it. Some game developers in the past have put tremendous time into making their in-game art beautiful only to have the game packaged in (and hidden behind) awful box art.

Vision: Of the five senses, vision is the one that gets the most attention from most game development teams. As a result, the fidelity of the visual experience that we can deliver to players has seen more obvious improvement over the past several years than that of any other sense. When thinking about the visible elements of your game, be sure to think beyond the 3D art in the game or the art of the board in a paper game. Realize that everything that players (or potential players) see that has anything to do with your game will affect their impression of it as well as their enjoyment of it. Some game developers in the past have put tremendous time into making their in-game art beautiful only to have the game packaged in (and hidden behind) awful box art.

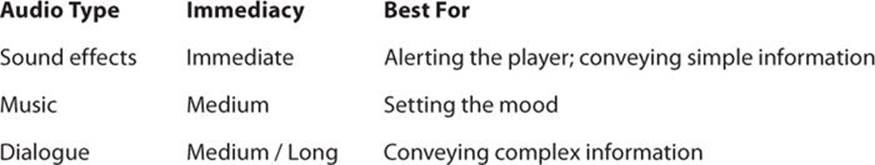

![]() Hearing: Audio in games is second only to video in the amazing level of fidelity that can be delivered to players. All modern consoles can output 5.1-channel sound, and some can do even better than that. Game audio is composed of sound effects, music, and dialogue. Each will take a different amount of time to be interpreted by the player, and each has a different best use. In addition, on a medium to large team, each of these three will usually be handled by a different artist.

Hearing: Audio in games is second only to video in the amazing level of fidelity that can be delivered to players. All modern consoles can output 5.1-channel sound, and some can do even better than that. Game audio is composed of sound effects, music, and dialogue. Each will take a different amount of time to be interpreted by the player, and each has a different best use. In addition, on a medium to large team, each of these three will usually be handled by a different artist.

Another aspect of audio to consider is background noise. For mobile games, you can almost always expect that the player is going to be in a nonoptimal audio situation when playing your game. Though audio can always add to a game, it’s just not prudent to make it a vital aspect of a mobile game unless it’s the core feature of the game (e.g., games like Papa Sangre by Somethin’ Else or Freeq by Psychic Bunny). There is also background noise in computer and console games to consider. Some cooling fans are very loud, and that needs to be considered when developing quiet audio for digital games.

![]() Touch: Touch is very different between board games and digital games, but in both cases, it’s the most direct contact that you have with the player. In a board game, touch comes down to the feel of the playing pieces, cards, board, and so on. Do the pieces for your game feel high quality or do they feel cheap? Often you want them to be the former, but the latter isn’t terrible. James Ernst, possibly the most prolific board game designer in the world for several years, ran a company called Cheap Ass Games, the mission of which was to get great games to players at as low a cost to them as possible. In order to cut costs, playing pieces were made of cheap materials, but this was fine with players because the games from his company cost less than $10 each instead of the $40-$50 that many board games cost. All design decisions are choices; just make sure that you’re aware of the options and know that you’re making a choice.

Touch: Touch is very different between board games and digital games, but in both cases, it’s the most direct contact that you have with the player. In a board game, touch comes down to the feel of the playing pieces, cards, board, and so on. Do the pieces for your game feel high quality or do they feel cheap? Often you want them to be the former, but the latter isn’t terrible. James Ernst, possibly the most prolific board game designer in the world for several years, ran a company called Cheap Ass Games, the mission of which was to get great games to players at as low a cost to them as possible. In order to cut costs, playing pieces were made of cheap materials, but this was fine with players because the games from his company cost less than $10 each instead of the $40-$50 that many board games cost. All design decisions are choices; just make sure that you’re aware of the options and know that you’re making a choice.

One of the most exciting recent technological advancements for board game prototyping is 3D printing, and many board game designers are starting to print pieces for their game prototypes. There are also several companies online now that will print your game board, cards, or pieces.

There are also aspects of touch in digital games. The way that the controller feels in a player’s hands and the amount of fatigue that it causes are definitely aspects that the designer needs to consider. When the fantastic PlayStation 2 game Okami was ported to the Nintendo Wii, the designers chose to change the attack command from a button press (the X on the PlayStation controller) to a waggle of the Wiimote (which mimicked the attack gesture from The Legend of Zelda: Twilight Princess that had done very well on the Wii). However, while attacks in the heat of battle in Twilight Princess happen about once every couple of seconds, attacks in Okami happen several times per second, so the attack gesture that worked well in Twilight Princess instead caused player fatigue in Okami. With the rise of tablet and smartphone gaming, touch and gesture are elements that every game designer must consider carefully.

Another aspect of touch in digital games is rumble-style player feedback. As a designer, you can choose the intensity and style of rumble feedback in most modern console controllers.

![]() Smell: Smell is not often a designed aspect of inscribed aesthetics, but it is there. Just as different book printing processes have different smells, so too do different board and card game printing processes. Make sure that you get a sample from your manufacturer before committing to printing 1,000 copies of something that might smell strange.

Smell: Smell is not often a designed aspect of inscribed aesthetics, but it is there. Just as different book printing processes have different smells, so too do different board and card game printing processes. Make sure that you get a sample from your manufacturer before committing to printing 1,000 copies of something that might smell strange.

Aesthetic Goals

When designing and developing the inscribed aesthetic elements of a game, we as game developers are taking advantage of hundreds of years of cultural understanding of other forms of art. Humankind has been making art and music since long before the dawn of written history. Interactive experiences have the advantage of being able to pull from all of that experience and of allowing us as designers to incorporate all of the techniques and knowledge of aesthetic art into the games that we create. However, when we do so, it must be done with a reason, and it must mesh cohesively with the other elements of the game. These are some of the goals that aesthetic elements can serve well in our games:

![]() Mood: Aesthetics do a fantastic job of helping to set the emotional mood of a game. While mood can definitely be conveyed through game mechanics, both visual art and music can do a fantastic job of influencing a player’s mood much faster than mechanics are able to.

Mood: Aesthetics do a fantastic job of helping to set the emotional mood of a game. While mood can definitely be conveyed through game mechanics, both visual art and music can do a fantastic job of influencing a player’s mood much faster than mechanics are able to.

![]() Information: Several informational colors are built in to our psyche as mammals. Things like the color red or alternating yellow and black are seen by nearly every species in the animal kingdom as indicators of danger. In contrast, cool colors like blue and green are usually seen as peaceful.

Information: Several informational colors are built in to our psyche as mammals. Things like the color red or alternating yellow and black are seen by nearly every species in the animal kingdom as indicators of danger. In contrast, cool colors like blue and green are usually seen as peaceful.

In addition, players can be trained to understand various aesthetics as having specific meaning. The LucasArts game X-Wing was the first to have a soundtrack that was procedurally generated by the in-game situation. The music would rise in intensity to warn the player that enemies were attacking. Similarly, as described in Chapter 13, the colors bright blue and yellow are used throughout the Naughty Dog game Uncharted 3 to help the player identify handholds and footholds for climbing.

Inscribed Narrative

As with all forms of experience, dramatics and narrative are an important part of many interactive experiences. However, game narratives face challenges that are not present in any form of linear media, and as such, writers are still learning how to craft and present interactive narratives. This section will explore the components of inscribed dramatics, purposes for which they are used, methods for storytelling in games, and differences between game narratives and linear narratives.

Components of Inscribed Narrative

In both linear and interactive narrative, the components of the dramatics are the same: premise, setting, character, and plot.

![]() Premise: The premise is the narrative basis from which the story emerges:4

Premise: The premise is the narrative basis from which the story emerges:4

4 These are the premises of Star Wars: A New Hope, Half-Life, and Assassin’s Creed 4: Black Flag.

A long time ago in a galaxy far, far away, an intergalactic war is brought to the doorstep of a young farmer who doesn’t yet realize the importance of his ancestry or himself.

Gordon Freeman has no idea about the surprises that are in store for him on his first day of work at the top secret Black Mesa research facility.

Edward Kenway must fight and pirate his way to fortune on the high seas of the Caribbean while discovering the secret of the mysterious Observatory, sought by Templars and Assassins alike.

![]() Setting: The setting expands upon the skeleton of the premise to provide a detailed world in which the narrative can take place. The setting can be something as large as a galaxy far, far away or as small as a tiny room beneath the stairs, but it’s important that it is believable within the bounds of the premise and that it is internally consistent; if your characters will choose to fight with swords in a world full of guns, you need to have a good reason for it.

Setting: The setting expands upon the skeleton of the premise to provide a detailed world in which the narrative can take place. The setting can be something as large as a galaxy far, far away or as small as a tiny room beneath the stairs, but it’s important that it is believable within the bounds of the premise and that it is internally consistent; if your characters will choose to fight with swords in a world full of guns, you need to have a good reason for it.

In Star Wars, when Obi Wan Kenobi gives the light saber to Luke, he answers all of these questions by stating that it is “not as clumsy or random as a blaster; an elegant weapon for a more civilized age.”

![]() Character: Stories are about characters, and the best stories are about characters we care about. Narratively, characters are composed of a backstory and one or more objectives. These combine to give the character a role in the story: protagonist, antagonist, companion, lackey, mentor, and so on.

Character: Stories are about characters, and the best stories are about characters we care about. Narratively, characters are composed of a backstory and one or more objectives. These combine to give the character a role in the story: protagonist, antagonist, companion, lackey, mentor, and so on.

![]() Plot: Plot is the sequence of events that take place in your narrative. Usually, this takes the form of the protagonist wanting something but having difficulty achieving it because of either an antagonist or an antagonistic situation getting in the way. The plot then becomes the story of how the protagonist attempts to overcome this difficulty or obstruction.

Plot: Plot is the sequence of events that take place in your narrative. Usually, this takes the form of the protagonist wanting something but having difficulty achieving it because of either an antagonist or an antagonistic situation getting in the way. The plot then becomes the story of how the protagonist attempts to overcome this difficulty or obstruction.

Traditional Dramatics

Though interactive narrative offers many new possibilities to writers and developers, it still generally follows traditional dramatic structures.

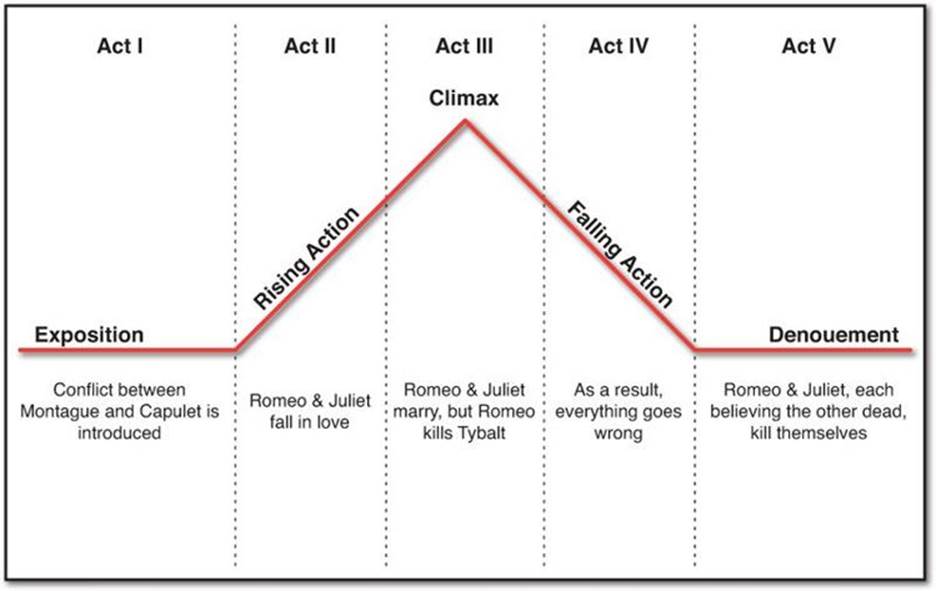

Five-Act Structure

German writer Gustav Freytag wrote about five-act structure in his 1863 book Die Technik des Dramas (The Technique of Dramas). It described the purpose of the five acts often used by Shakespeare and many of his contemporaries (as well as Roman playwrights) and proposed what has come to be known as Freytag’s pyramid (see Figure 4.2). The vertical axis in Figures 4.2 and 4.3 represents the level of audience excitement at that point in the story.

Figure 4.2 Freytag’s pyramid of five-act structure showing examples from Romeo and Juliet by Shakespeare

According to Freytag, the acts work as follows:

![]() Act I: Exposition: Introduces the narrative premise, the setting, and the important characters. In Act I of William Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet, we are introduced to Verona, Italy, and the feud between the powerful Montague and Capulet families. Romeo is introduced as the son of the Montague family and is infatuated with Rosaline.

Act I: Exposition: Introduces the narrative premise, the setting, and the important characters. In Act I of William Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet, we are introduced to Verona, Italy, and the feud between the powerful Montague and Capulet families. Romeo is introduced as the son of the Montague family and is infatuated with Rosaline.

![]() Act II: Rising action: Something happens that causes new tension for the important characters, and the dramatic tension rises. Romeo sneaks into the Capulet’s ball and is instantly smitten with Juliet, the daughter of the Capulet family.

Act II: Rising action: Something happens that causes new tension for the important characters, and the dramatic tension rises. Romeo sneaks into the Capulet’s ball and is instantly smitten with Juliet, the daughter of the Capulet family.

![]() Act III: Climax: Everything comes to a head, and the outcome of the play is decided. Romeo and Juliet are secretly married, and the local friar hopes that this may lead to peace between their families. However, the next morning, Romeo is accosted by Juliet’s cousin Tybalt. Romeo won’t fight, so his friend Mercutio fights in his stead, and Tybalt accidentally kills Mercutio (because Romeo got in the way). Romeo is furious and chases Tybalt, eventually killing him. Romeo’s decision to kill Tybalt is the moment of climax of the play because before that moment, it seems like everything might work out for the two lovers, and after that moment, the audience knows that things will end horribly.

Act III: Climax: Everything comes to a head, and the outcome of the play is decided. Romeo and Juliet are secretly married, and the local friar hopes that this may lead to peace between their families. However, the next morning, Romeo is accosted by Juliet’s cousin Tybalt. Romeo won’t fight, so his friend Mercutio fights in his stead, and Tybalt accidentally kills Mercutio (because Romeo got in the way). Romeo is furious and chases Tybalt, eventually killing him. Romeo’s decision to kill Tybalt is the moment of climax of the play because before that moment, it seems like everything might work out for the two lovers, and after that moment, the audience knows that things will end horribly.

![]() Act IV: Falling action: The play continues toward its inevitable conclusion. If it’s a comedy, things get better; if it’s a tragedy, they may appear to be getting better, but it just gets worse. The results of the climax are played out for the audience. Romeo is banished from Verona. The friar concocts a plan to allow Romeo and Juliet to escape together. He has Juliet fake her death and sends a message to Romeo to let him know, but the messenger never makes it to Romeo.

Act IV: Falling action: The play continues toward its inevitable conclusion. If it’s a comedy, things get better; if it’s a tragedy, they may appear to be getting better, but it just gets worse. The results of the climax are played out for the audience. Romeo is banished from Verona. The friar concocts a plan to allow Romeo and Juliet to escape together. He has Juliet fake her death and sends a message to Romeo to let him know, but the messenger never makes it to Romeo.

![]() Act V: Denouement (pronounced “day-new-maw”): The play resolves. Romeo enters the tomb believing Juliet to be truly dead and kills himself. She immediately awakens to find him dead and then kills herself as well. The families become aware of this tragedy, and everyone weeps, promising to cease the feud.

Act V: Denouement (pronounced “day-new-maw”): The play resolves. Romeo enters the tomb believing Juliet to be truly dead and kills himself. She immediately awakens to find him dead and then kills herself as well. The families become aware of this tragedy, and everyone weeps, promising to cease the feud.

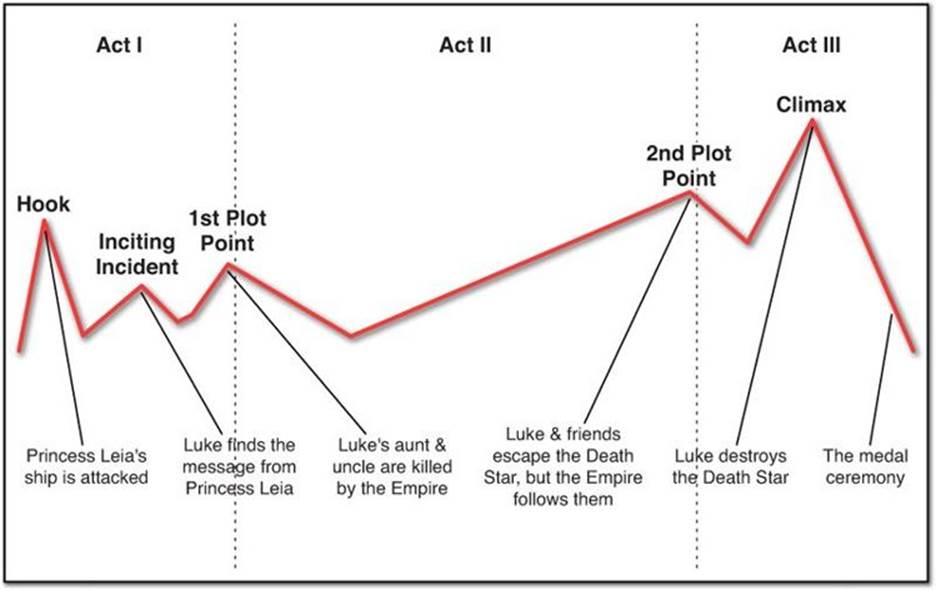

Three-Act Structure

In his books and lectures, American screenwriter Syd Field has proposed another way of understanding traditional narrative in terms of three acts.5 Between each act, a plot point changes the direction of the story and forces the characters’ actions. Figure 4.3 provides an example that is further explained in the following list:

5 Syd Field, Screenplay: The Foundations of Screenwriting (New York: Delta Trade Paperbacks, 2005).

![]() Act I: Exposition: Introduces the audience to the world of the narrative and presents the premise, setting, and main characters. In Act I of Star Wars, Luke is a young, idealistic kid who works on his uncle’s moisture farm. There’s a galactic rebellion happening against a fascist Empire, but he’s just a simple farmer dreaming of flying starfighters.

Act I: Exposition: Introduces the audience to the world of the narrative and presents the premise, setting, and main characters. In Act I of Star Wars, Luke is a young, idealistic kid who works on his uncle’s moisture farm. There’s a galactic rebellion happening against a fascist Empire, but he’s just a simple farmer dreaming of flying starfighters.

![]() Hook: Gets the audience’s attention quickly. According to Field, an audience decides in the first few minutes whether they’re going to watch a film, so the first few minutes should be really exciting, even if the action in them has nothing to do with the rest of the film (e.g., the beginning of any James Bond film). In Star Wars, the opening scene of Princess Leia’s ship being attacked had some of the best special visual effects that 1977 audiences had ever seen and a fantastic score by John Williams, both of which helped make it an exciting hook.

Hook: Gets the audience’s attention quickly. According to Field, an audience decides in the first few minutes whether they’re going to watch a film, so the first few minutes should be really exciting, even if the action in them has nothing to do with the rest of the film (e.g., the beginning of any James Bond film). In Star Wars, the opening scene of Princess Leia’s ship being attacked had some of the best special visual effects that 1977 audiences had ever seen and a fantastic score by John Williams, both of which helped make it an exciting hook.

![]() Inciting Incident: An event enters the life of the main character, causing her to start the adventure. Luke is leading a pretty normal life until he finds Leia’s secret message stored inside of R2-D2. This discovery causes him to seek out “Old Ben” Kenobi, who changes his life.

Inciting Incident: An event enters the life of the main character, causing her to start the adventure. Luke is leading a pretty normal life until he finds Leia’s secret message stored inside of R2-D2. This discovery causes him to seek out “Old Ben” Kenobi, who changes his life.

![]() First Plot Point: The first plot point ends the first act and pushes the protagonist down the path toward the second. Luke has decided to stay home and not help Obi-Wan Kenobi, but when he finds that the Empire has killed his aunt and uncle, he changes his mind and decides to join Obi-Wan and train to become a Jedi.

First Plot Point: The first plot point ends the first act and pushes the protagonist down the path toward the second. Luke has decided to stay home and not help Obi-Wan Kenobi, but when he finds that the Empire has killed his aunt and uncle, he changes his mind and decides to join Obi-Wan and train to become a Jedi.

![]() Act II: Antagonism: The protagonist starts on her journey, but a series of obstacles get in her way. Luke and Obi-Wan hire Han Solo and Chewbacca to help them deliver the secret plans carried by R2-D2 to Alderaan, however when they arrive, Alderaan has been destroyed, and their ship is captured by the Death Star.

Act II: Antagonism: The protagonist starts on her journey, but a series of obstacles get in her way. Luke and Obi-Wan hire Han Solo and Chewbacca to help them deliver the secret plans carried by R2-D2 to Alderaan, however when they arrive, Alderaan has been destroyed, and their ship is captured by the Death Star.

![]() Second Plot Point: The second plot point ends the second act and pushes the protagonist into her decision of what she will attempt in the third act. After much struggle, Luke and his friends escape from the Death Star with both the princess and the plans, but his mentor, Obi-Wan Kenobi, is killed in the process. The Death Star follows them to the rebel’s secret base, and Luke must choose whether to aid in the attack on the Death Star or leave with Han Solo.

Second Plot Point: The second plot point ends the second act and pushes the protagonist into her decision of what she will attempt in the third act. After much struggle, Luke and his friends escape from the Death Star with both the princess and the plans, but his mentor, Obi-Wan Kenobi, is killed in the process. The Death Star follows them to the rebel’s secret base, and Luke must choose whether to aid in the attack on the Death Star or leave with Han Solo.

![]() Act III: Resolution: The story is concluded, and the protagonist either succeeds or fails. Either way, she emerges from the story with a new understanding of who she is. Luke chooses to help attack the Death Star and ends up saving the day.

Act III: Resolution: The story is concluded, and the protagonist either succeeds or fails. Either way, she emerges from the story with a new understanding of who she is. Luke chooses to help attack the Death Star and ends up saving the day.

![]() Climax: The moment when everything comes to a head, and the main question of the plot is answered. Luke is alone in the Death Star trench having lost both his wingmen and R2-D2. Just as he is about to be shot down by Darth Vader, Han and Chewbacca appear to save him, allowing him a clean shot. Luke chooses to trust the Force over technology and shoots with his eyes closed, making an extremely difficult shot and destroying the Death Star.

Climax: The moment when everything comes to a head, and the main question of the plot is answered. Luke is alone in the Death Star trench having lost both his wingmen and R2-D2. Just as he is about to be shot down by Darth Vader, Han and Chewbacca appear to save him, allowing him a clean shot. Luke chooses to trust the Force over technology and shoots with his eyes closed, making an extremely difficult shot and destroying the Death Star.

Figure 4.3 Three-act structure, with examples from Star Wars: A New Hope

In most modern movies and in nearly all video games, the climax is very close to the end of the narrative with very little time for falling action or denouement. One marked example of this not being the case is the game Red Dead Redemption by Rockstar Games. After the big climax where the main character, John Marston, finally defeats the man the government hired him to kill, he is allowed to go home to his family, with the game playing its only sung musical track as John rides home slowly in the snow. Then, the player is subjected to a series of rather dull missions where John clears crows out of their grain silo, teaches his petulant son to wrangle cattle, and does other chores around the house. The player feels the boredom of these missions much like John does. Then, the same government agents that initially hired John come to his farm to kill him, eventually succeeding in their task. Once John dies, the game fades to black and fades back in on the player in the role of Jack (John’s son) three years after his father’s death. The game returns to more action-based missions as Jack attempts to track down the agents who killed his father. This kind of falling action is rare and refreshing to see in games, and it made the narrative of Red Dead Redemption one of the most memorable that I’ve played.

Differences Between Interactive and Linear Narrative

At their core, interactive and linear narratives are quite different because of the difference in the role of the audience versus the player. Though an audience member of course brings her own background and interpretations to any media that she consumes, she is still unable to change the actual media itself, only her perception thereof. However, a player is constantly affecting the media in which she is taking part, and therefore a player has actual agency in the interactive narratives that she experiences. This means that authors of interactive narrative must be aware of some core differences in how they can craft their narratives.

Plot Versus Free Will

One of the most difficult things to give up when crafting interactive narratives is control over the plot. Both authors and readers/viewers are accustomed to plots with elements like foreshadowing, fate, irony, and other ways in which the intended outcome of the plot actually influences earlier parts of the story. In a truly interactive experience, this would be impossible because of the free will of the player. Without knowing what choices the player will make, it is very difficult to intentionally foreshadow the results of those choices. There are several possibilities for dealing with this dichotomy, some of which are used often and others of which are used in situations like pen-and-paper RPGs but have not yet been implemented in many digital games:

![]() Limited possibilities: Limited possibilities are actually a part of nearly all interactive narrative experiences. In fact, most games, at their inscribed level, are not actually interactive narratives. All the most popular series of games over the past decade (Prince of Persia, Call of Duty,Halo, Uncharted, and so on) have exclusively linear stories at their core. No matter what you do in the game, your choices are to either continue with the narrative or quit the game. In fact, Spec Ops: The Line by Yager Development explored this issue beautifully, placing the player and the main character of the story in the same position of having only two real choices: continue to perform increasingly horrific acts or just stop playing the game. In Prince of Persia: The Sands of Time, this is handled by having the narrator (the prince of the title and the protagonist) say “No, no, no; that’s not the way it happened. Shall I start again?” whenever the player dies and the game has to back up to the most recent check point. In the Assassin’s Creed series, this is handled by stating that you have become “desynchronized” from your ancestor’s story if (through lack of player skill) the ancestor is allowed to die.

Limited possibilities: Limited possibilities are actually a part of nearly all interactive narrative experiences. In fact, most games, at their inscribed level, are not actually interactive narratives. All the most popular series of games over the past decade (Prince of Persia, Call of Duty,Halo, Uncharted, and so on) have exclusively linear stories at their core. No matter what you do in the game, your choices are to either continue with the narrative or quit the game. In fact, Spec Ops: The Line by Yager Development explored this issue beautifully, placing the player and the main character of the story in the same position of having only two real choices: continue to perform increasingly horrific acts or just stop playing the game. In Prince of Persia: The Sands of Time, this is handled by having the narrator (the prince of the title and the protagonist) say “No, no, no; that’s not the way it happened. Shall I start again?” whenever the player dies and the game has to back up to the most recent check point. In the Assassin’s Creed series, this is handled by stating that you have become “desynchronized” from your ancestor’s story if (through lack of player skill) the ancestor is allowed to die.

There are also several examples of games that limit choices to only a few possibilities and base those on the player’s actions throughout the game. Both Fable, by Lionhead Studios, and Star Wars: Knights of the Old Republic, by Bioware, claimed to be watching the player throughout the game to determine the final game outcome, but though each did track the player on a good versus evil scale throughout the game, in both cases (as in many other games), a single choice made at the end of the game could override an entire game of good or evil behavior.

Other games like the Japanese RPGs Final Fantasy VII and Chrono Trigger have more subtle and varied possibilities. In Final Fantasy VII, there is a point where the main character, Cloud, goes on a date with someone at the Golden Saucer amusement part. The default is for Cloud to go out with Aeris; however, if the player has ignored Aeris throughout the game and kept her out of their battle party, Cloud will instead go out with Tifa. The possibilities for the date are the characters Aeris, Tifa, Yuffie, and Barrett, although it takes resolute effort to have the date with Barrett. The game never explains that this math is happening in the background but it is always there, and the Final Fantasy team used a similar strategy in Final Fantasy X to determine who the protagonist, Tidus, would ride on a snowmobile with in a romantic scene. Chrono Trigger uses several metrics to determine which of the game’s thirteen endings to choose (and some of those endings have multiple possibilities within them). Again, the calculations for this are largely invisible to the player.

![]() Allow the player to choose from several linear side quests: Many of Bethesda Softwork’s open-world games use this strategy, including the recent games Fallout 3 and Skyrim. While the main quest is generally pretty linear for these games, it is only a small fraction of the game’s total content. In Skyrim, for instance, the main quest takes about 12 to 16 hours to complete, but the game has over 400 hours of additional side quests. A player’s reputation and history in the game lead to some side quests being unlocked and exclude her from playing others. This means that each individual who plays the game has the potential to have a different combination of linear experiences that add up to a different overall game experience from other players.

Allow the player to choose from several linear side quests: Many of Bethesda Softwork’s open-world games use this strategy, including the recent games Fallout 3 and Skyrim. While the main quest is generally pretty linear for these games, it is only a small fraction of the game’s total content. In Skyrim, for instance, the main quest takes about 12 to 16 hours to complete, but the game has over 400 hours of additional side quests. A player’s reputation and history in the game lead to some side quests being unlocked and exclude her from playing others. This means that each individual who plays the game has the potential to have a different combination of linear experiences that add up to a different overall game experience from other players.

![]() Foreshadowing multiple things: If you foreshadow several different things that might happen, some of them probably will happen. Players will generally ignore the foreshadowing that is not paid off while noticing that which does. This happens often in serial television shows where several possibilities for future plots are put in place but only a few are ever actually executed (e.g., the Nebari plot to take over the universe that is revealed in the Farscape episode “A Clockwork Nebari” and the character of the Doctor’s daughter from the Doctor Who episode “The Doctor’s Daughter” who never returns to the show).

Foreshadowing multiple things: If you foreshadow several different things that might happen, some of them probably will happen. Players will generally ignore the foreshadowing that is not paid off while noticing that which does. This happens often in serial television shows where several possibilities for future plots are put in place but only a few are ever actually executed (e.g., the Nebari plot to take over the universe that is revealed in the Farscape episode “A Clockwork Nebari” and the character of the Doctor’s daughter from the Doctor Who episode “The Doctor’s Daughter” who never returns to the show).

![]() Develop minor nonplayer characters (NPCs) into major ones: This is a tactic used often by game masters of pen-and-paper RPGs. An example of this would be if the players were attacked by a group of ten bandits, and the players defeated the bandits, but one got away. The game master (GM) could then choose to have that bandit return at some point with a vendetta against the players for killing his friends. This differs significantly from games like Final Fantasy VI (originally titled Final Fantasy III in the U.S.), where it is pretty obvious from early in the game that Kefka will be a recurring, annoying, and eventually wholly evil nemesis character. Though the characters in the player’s party don’t realize this, just the fact that the developers chose to give Kefka a special sound effect for his laugh makes it apparent to the player.

Develop minor nonplayer characters (NPCs) into major ones: This is a tactic used often by game masters of pen-and-paper RPGs. An example of this would be if the players were attacked by a group of ten bandits, and the players defeated the bandits, but one got away. The game master (GM) could then choose to have that bandit return at some point with a vendetta against the players for killing his friends. This differs significantly from games like Final Fantasy VI (originally titled Final Fantasy III in the U.S.), where it is pretty obvious from early in the game that Kefka will be a recurring, annoying, and eventually wholly evil nemesis character. Though the characters in the player’s party don’t realize this, just the fact that the developers chose to give Kefka a special sound effect for his laugh makes it apparent to the player.

Tip

Pen-and-paper RPGs still offer players a unique interactive gaming experience, and I highly recommend them. In fact, when I taught at the University of Southern California, I required all of my students to run an RPG and play in a couple run by their peers. Roughly 40% of the students each semester listed it as their favorite assignment.

Because pen-and-paper RPGs are run by a person, that game master (GM) can craft the narrative in real time for the players in a way that computers have yet to match. All of the strategies listed earlier are used by GMs to guide their players and make their experiences seem fated, foreshadowed, or ironic in ways that are usually reserved for linear narrative.

The perennial RPG Dungeons & Dragons, by Wizards of the Coast, is a good place to get started, and there are a tremendous number of source books for it. However, I have found that D&D campaigns tend to be very combat focused. For an experience that allows you to most easily create and experience interactive stories, I recommend the FATE system by Evil Hat Productions.

Empathetic Character Versus Avatar

In linear narratives, the protagonist is often a character with whom the audience is expected to empathize. When the audience watches Romeo and Juliet make stupid decisions, they remember being young themselves and empathize with the feelings that lead the two lovers down their fatal path. In contrast, the protagonist in an interactive narrative is not a character separate from the player but instead the player’s avatar in the world. (Avatar is a word from Sanskrit that refers to the physical embodiment of a god on Earth; in games, it is the virtual embodiment of the player in the game world.) This can lead to a dissonance between the actions and personality that the player would like to have in the world and the personality of the player-character (PC). For me, this was driven home by my experience with Cloud Strife as the protagonist of Final Fantasy VII. Throughout the game, Cloud was a little more petulant than I would have liked, but in general, his silence allowed me to project my own character on to him. However, after a pivotal scene where Cloud loses someone close to him, he chose to sit, unresponsive in a wheelchair instead of fighting to save the world from Sephiroth, as I wanted to. This dichotomy between the PC’s choice and the choice that I as the player wanted to make was extremely frustrating for me.

A fantastic example of this dichotomy being used to great effect happens in the Clover Studio game Okami. In Okami, the player character is Amaterasu, a reincarnation of the female god of the sun in the form of a white wolf. However, Amaterasu’s powers have diminished over the past 100 years, and the player must work to reclaim them. About a quarter of the way through the narrative, the main antagonist, the demon Orochi, chooses a maiden to be sacrificed to him. Both the player and Amaterasu’s companion, Issun, know that Amaterasu has only regained a few of her powers at this point, and the player feels wary of facing Orochi in such a weakened state. However, despite Issun’s protests, Amaterasu runs directly to the fight. As the music swells in support of her decision, my feelings as a player changed from trepidation to temerity, and I actually felt like a hero because I knew that the odds were against me, but I was still doing what needed to be done.

This character versus avatar dichotomy has been approached several ways in games and interactive narrative:

![]() Role fulfillment: By far, the most common approach in games is to have the player roleplay the game character. When playing character-driven games like the Tomb Raider or Uncharted series, the player is playing not themselves but instead Lara Croft or Nathan Drake. The player sets aside her own personality to fulfill the inscribed personality of the game’s protagonist.

Role fulfillment: By far, the most common approach in games is to have the player roleplay the game character. When playing character-driven games like the Tomb Raider or Uncharted series, the player is playing not themselves but instead Lara Croft or Nathan Drake. The player sets aside her own personality to fulfill the inscribed personality of the game’s protagonist.

![]() The silent protagonist: In a tradition reaching at least as far back as the first Legend of Zelda game, many protagonists are largely silent. Other characters talk to them and react as if they’ve said things, but the player never sees the statements made by the player character. This was done with the idea that the player could then impress her own personality on the protagonist rather than being forced into a personality inscribed by the game developers. However, regardless of what Link says or doesn’t say, his personality is demonstrated rather clearly by his actions, and even without Cloud saying a word, players can still experience a dissonance between their wishes and his actions as described in the preceding example.

The silent protagonist: In a tradition reaching at least as far back as the first Legend of Zelda game, many protagonists are largely silent. Other characters talk to them and react as if they’ve said things, but the player never sees the statements made by the player character. This was done with the idea that the player could then impress her own personality on the protagonist rather than being forced into a personality inscribed by the game developers. However, regardless of what Link says or doesn’t say, his personality is demonstrated rather clearly by his actions, and even without Cloud saying a word, players can still experience a dissonance between their wishes and his actions as described in the preceding example.

![]() Multiple dialogue choices: Many games offer the player multiple dialogue choices for her character, which can certainly help the player to feel more in control of the character and her personality. However, there are a couple of important requirements:

Multiple dialogue choices: Many games offer the player multiple dialogue choices for her character, which can certainly help the player to feel more in control of the character and her personality. However, there are a couple of important requirements:

![]() The player must understand the implications of her statement: Sometimes, a line that may seem entirely clear to the game’s writers does not seem to have the same connotations to the player. If the player chooses dialogue that seems to her to be complimentary, but the writer meant for it to be antagonistic, the NPC’s reaction can seem very strange to the player.

The player must understand the implications of her statement: Sometimes, a line that may seem entirely clear to the game’s writers does not seem to have the same connotations to the player. If the player chooses dialogue that seems to her to be complimentary, but the writer meant for it to be antagonistic, the NPC’s reaction can seem very strange to the player.

![]() The choice of statement must matter: Some games offer the player a fake choice, anticipating that she will make the choice that the game desires. If, for instance, she’s asked to save the world, and she just says “no,” it will respond with something like “oh, you can’t mean that,” and not actually allow her a satisfactory choice.

The choice of statement must matter: Some games offer the player a fake choice, anticipating that she will make the choice that the game desires. If, for instance, she’s asked to save the world, and she just says “no,” it will respond with something like “oh, you can’t mean that,” and not actually allow her a satisfactory choice.

One fantastic example of this being done well is the dialog wheel in the Mass Effect series by Bioware. In these games, the player is presented with a wheel of dialog choices, and the sections of the wheel are coded with meaning. A choice on the left side of the wheel will extend the conversation, while one on the right side will shorten it. A choice on the top of the wheel will be friendly, while one on the bottom will be surly or antagonistic. By positioning the dialog options in this way, the player is granted important information about the connotations of her choice and is not surprised by the outcome.

Another very different but equally compelling example is Blade Runner by Westwood Studios. The designers felt that choosing dialog options interrupted the flow of the player experience, so instead of offering the player a choice between dialogue options at every statement, the player was able to choose a mood for her character (friendly, neutral, surly, or random). The protagonist would act and speak as dictated by his mood without any interruption in the narrative flow, and the player could change the mood at any time to alter her character’s response to the situation.

![]() Track player actions and react accordingly: Some games now track the player’s relationships with various factions and have the faction members react to the player accordingly. Do a favor for the Orcs, and they may let you sell goods at their trading post. Arrest a member of the Thieves Guild, and you may find yourself mugged by them in the future. This is a common feature of open-world western roleplaying games like those by Bethesda Softworks and is in some ways based on the morality system of eight virtues and three principles that was introduced inUltima IV, by Origin Systems, one of the first examples of complex morality systems in a digital game.

Track player actions and react accordingly: Some games now track the player’s relationships with various factions and have the faction members react to the player accordingly. Do a favor for the Orcs, and they may let you sell goods at their trading post. Arrest a member of the Thieves Guild, and you may find yourself mugged by them in the future. This is a common feature of open-world western roleplaying games like those by Bethesda Softworks and is in some ways based on the morality system of eight virtues and three principles that was introduced inUltima IV, by Origin Systems, one of the first examples of complex morality systems in a digital game.

Purposes for Inscribed Dramatics

Inscribed dramatics can serve several purposes in game design:

![]() Evoking emotion: Over the past several centuries, writers have gained skill in manipulating the emotions of their audiences through dramatics. This holds true in games and interactive narrative as well, and even purely linear narrative inscribed over a game can focus and shape the player’s feelings.

Evoking emotion: Over the past several centuries, writers have gained skill in manipulating the emotions of their audiences through dramatics. This holds true in games and interactive narrative as well, and even purely linear narrative inscribed over a game can focus and shape the player’s feelings.

![]() Motivation and justification: Just as dramatics can shape emotions, they can also be used to encourage the player to take certain actions or to justify actions if those actions seem distasteful. This is very true of the fantastic retelling of Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness in the gameSpec Ops: The Line. A more positive example comes from The Legend of Zelda: The Wind Waker. At the beginning of the game, Link’s sister Aryll lets him borrow her telescope for one day because it’s his birthday. On the same day, she is kidnapped by a giant bird, and the first part of the game is driven narratively by Link’s desire to rescue her. The inscribed storytelling of her giving something to the player before being kidnapped increases the player’s personal desire to rescue her.

Motivation and justification: Just as dramatics can shape emotions, they can also be used to encourage the player to take certain actions or to justify actions if those actions seem distasteful. This is very true of the fantastic retelling of Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness in the gameSpec Ops: The Line. A more positive example comes from The Legend of Zelda: The Wind Waker. At the beginning of the game, Link’s sister Aryll lets him borrow her telescope for one day because it’s his birthday. On the same day, she is kidnapped by a giant bird, and the first part of the game is driven narratively by Link’s desire to rescue her. The inscribed storytelling of her giving something to the player before being kidnapped increases the player’s personal desire to rescue her.

![]() Progression and reward: Many games use cut scenes and other inscribed narrative to help the player know where she is in the story and to reward her for progression. If the narrative of a game is largely linear, the player’s understanding of traditional narrative structure can help her to understand where in the three-act structure the game narrative currently is, and thereby, she can tell how far she has progressed in the overall plot of the game. Narrative cut scenes are also often used as rewards for players to mark the end of a level or other section of the game. This is true in the single-player modes of nearly all top-selling games with linear narratives (e.g., the Modern Warfare, Halo, and Uncharted series).

Progression and reward: Many games use cut scenes and other inscribed narrative to help the player know where she is in the story and to reward her for progression. If the narrative of a game is largely linear, the player’s understanding of traditional narrative structure can help her to understand where in the three-act structure the game narrative currently is, and thereby, she can tell how far she has progressed in the overall plot of the game. Narrative cut scenes are also often used as rewards for players to mark the end of a level or other section of the game. This is true in the single-player modes of nearly all top-selling games with linear narratives (e.g., the Modern Warfare, Halo, and Uncharted series).

![]() Mechanics reinforcement: One of the most critical purposes of inscribed dramatics is the reinforcement of game mechanics. The German board game Up the River by Ravensburger is a fantastic example of this. In the game, players are trying to move their three boats up a board that is constantly moving backward. Calling the board a “river” reinforces the backward movement game mechanic. A board space that stops forward progress is called a “sandbar” (as boats often get hung up on sandbars), the space that pushes the player forward is called a “high tide.” Because each of these elements has dramatics associated with it, it is much easier to remember than, for instance, if the player were asked to remember that space number 3 stopped the boat and number 7 moved the boat forward.