C# 5.0 in a Nutshell (2012)

Chapter 8. LINQ Queries

LINQ, or Language Integrated Query, is a set of language and framework features for writing structured type-safe queries over local object collections and remote data sources. LINQ was introduced in C# 3.0 and Framework 3.5.

LINQ enables you to query any collection implementing IEnumerable<T>, whether an array, list, or XML DOM, as well as remote data sources, such as tables in SQL Server. LINQ offers the benefits of both compile-time type checking and dynamic query composition.

This chapter describes the LINQ architecture and the fundamentals of writing queries. All core types are defined in the System.Linq and System.Linq.Expressions namespaces.

NOTE

The examples in this and the following two chapters are preloaded into an interactive querying tool called LINQPad. You can download LINQPad from http://www.linqpad.net.

Getting Started

The basic units of data in LINQ are sequences and elements. A sequence is any object that implements IEnumerable<T> and an element is each item in the sequence. In the following example, names is a sequence, and "Tom", "Dick", and "Harry" are elements:

string[] names = { "Tom", "Dick", "Harry" };

We call this a local sequence because it represents a local collection of objects in memory.

A query operator is a method that transforms a sequence. A typical query operator accepts an input sequence and emits a transformed output sequence. In the Enumerable class in System.Linq, there are around 40 query operators—all implemented as static extension methods. These are called standard query operators.

NOTE

Queries that operate over local sequences are called local queries or LINQ-to-objects queries.

LINQ also supports sequences that can be dynamically fed from a remote data source such as a SQL Server. These sequences additionally implement the IQueryable<T> interface and are supported through a matching set of standard query operators in the Queryable class. We discuss this further in the section Interpreted Queries in this chapter.

A query is an expression that, when enumerated, transforms sequences with query operators. The simplest query comprises one input sequence and one operator. For instance, we can apply the Where operator on a simple array to extract those whose length is at least four characters as follows:

string[] names = { "Tom", "Dick", "Harry" };

IEnumerable<string> filteredNames = System.Linq.Enumerable.Where

(names, n => n.Length >= 4);

foreach (string n in filteredNames)

Console.WriteLine (n);

Dick

Harry

Because the standard query operators are implemented as extension methods, we can call Where directly on names—as though it were an instance method:

IEnumerable<string> filteredNames = names.Where (n => n.Length >= 4);

For this to compile, you must import the System.Linq namespace. Here’s a complete example:

using System;

usign System.Collections.Generic;

using System.Linq;

class LinqDemo

{

static void Main()

{

string[] names = { "Tom", "Dick", "Harry" };

IEnumerable<string> filteredNames = names.Where (n => n.Length >= 4);

foreach (string name in filteredNames) Console.WriteLine (name);

}

}

Dick

Harry

NOTE

We could further shorten our code by implicitly typing filteredNames:

var filteredNames = names.Where (n => n.Length >= 4);

This can hinder readability, however, particularly outside of an IDE, where there are no tool tips to help.

In this chapter, we avoid implicitly typing query results except when it’s mandatory (as we’ll see later, in the section Projection Strategies), or when a query’s type is irrelevant to an example.

Most query operators accept a lambda expression as an argument. The lambda expression helps guide and shape the query. In our example, the lambda expression is as follows:

n => n.Length >= 4

The input argument corresponds to an input element. In this case, the input argument n represents each name in the array and is of type string. The Where operator requires that the lambda expression return a bool value, which if true, indicates that the element should be included in the output sequence. Here’s its signature:

public static IEnumerable<TSource> Where<TSource>

(this IEnumerable<TSource> source, Func<TSource,bool> predicate)

The following query retrieves all names that contain the letter “a”:

IEnumerable<string> filteredNames = names.Where (n => n.Contains ("a"));

foreach (string name in filteredNames)

Console.WriteLine (name); // Harry

So far, we’ve built queries using extension methods and lambda expressions. As we’ll see shortly, this strategy is highly composable in that it allows the chaining of query operators. In the book, we refer to this as fluent syntax.[7] C# also provides another syntax for writing queries, calledquery expression syntax. Here’s our preceding query written as a query expression:

IEnumerable<string> filteredNames = from n in names

where n.Contains ("a")

select n;

Fluent syntax and query syntax are complementary. In the following two sections, we explore each in more detail.

Fluent Syntax

Fluent syntax is the most flexible and fundamental. In this section, we describe how to chain query operators to form more complex queries—and show why extension methods are important to this process. We also describe how to formulate lambda expressions for a query operator and introduce several new query operators.

Chaining Query Operators

In the preceding section, we showed two simple queries, each comprising a single query operator. To build more complex queries, you append additional query operators to the expression, creating a chain. To illustrate, the following query extracts all strings containing the letter “a”, sorts them by length, and then converts the results to uppercase:

using System;

using System.Collections.Generic;

using System.Linq;

class LinqDemo

{

static void Main()

{

string[] names = { "Tom", "Dick", "Harry", "Mary", "Jay" };

IEnumerable<string> query = names

.Where (n => n.Contains ("a"))

.OrderBy (n => n.Length)

.Select (n => n.ToUpper());

foreach (string name in query) Console.WriteLine (name);

}

}

JAY

MARY

HARRY

NOTE

The variable, n, in our example, is privately scoped to each of the lambda expressions. We can reuse n for the same reason we can reuse c in the following method:

void Test()

{

foreach (char c in "string1") Console.Write (c);

foreach (char c in "string2") Console.Write (c);

foreach (char c in "string3") Console.Write (c);

}

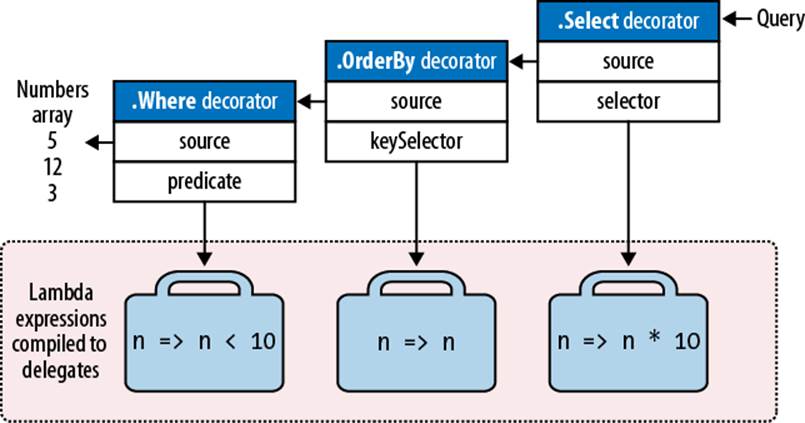

Where, OrderBy, and Select are standard query operators that resolve to extension methods in the Enumerable class (if you import the System.Linq namespace).

We already introduced the Where operator, which emits a filtered version of the input sequence. The OrderBy operator emits a sorted version of its input sequence; the Select method emits a sequence where each input element is transformed or projected with a given lambda expression (n.ToUpper(), in this case). Data flows from left to right through the chain of operators, so the data is first filtered, then sorted, then projected.

WARNING

A query operator never alters the input sequence; instead, it returns a new sequence. This is consistent with the functional programming paradigm, from which LINQ was inspired.

Here are the signatures of each of these extension methods (with the OrderBy signature simplified slightly):

public static IEnumerable<TSource> Where<TSource>

(this IEnumerable<TSource> source, Func<TSource,bool> predicate)

public static IEnumerable<TSource> OrderBy<TSource,TKey>

(this IEnumerable<TSource> source, Func<TSource,TKey> keySelector)

public static IEnumerable<TResult> Select<TSource,TResult>

(this IEnumerable<TSource> source, Func<TSource,TResult> selector)

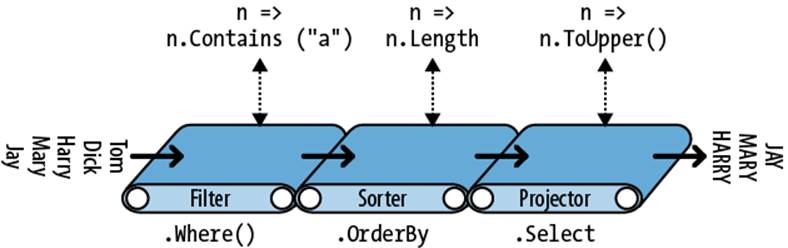

When query operators are chained as in this example, the output sequence of one operator is the input sequence of the next. The end result resembles a production line of conveyor belts, as illustrated in Figure 8-1.

Figure 8-1. Chaining query operators

We can construct the identical query progressively, as follows:

// You must import the System.Linq namespace for this to compile:

IEnumerable<string> filtered = names .Where (n => n.Contains ("a"));

IEnumerable<string> sorted = filtered.OrderBy (n => n.Length);

IEnumerable<string> finalQuery = sorted .Select (n => n.ToUpper());

finalQuery is compositionally identical to the query we had constructed previously. Further, each intermediate step also comprises a valid query that we can execute:

foreach (string name in filtered)

Console.Write (name + "|"); // Harry|Mary|Jay|

Console.WriteLine();

foreach (string name in sorted)

Console.Write (name + "|"); // Jay|Mary|Harry|

Console.WriteLine();

foreach (string name in finalQuery)

Console.Write (name + "|"); // JAY|MARY|HARRY|

Why extension methods are important

Instead of using extension method syntax, you can use conventional static method syntax to call the query operators. For example:

IEnumerable<string> filtered = Enumerable.Where (names,

n => n.Contains ("a"));

IEnumerable<string> sorted = Enumerable.OrderBy (filtered, n => n.Length);

IEnumerable<string> finalQuery = Enumerable.Select (sorted,

n => n.ToUpper());

This is, in fact, how the compiler translates extension method calls. Shunning extension methods comes at a cost, however, if you want to write a query in a single statement as we did earlier. Let’s revisit the single-statement query—first in extension method syntax:

IEnumerable<string> query = names.Where (n => n.Contains ("a"))

.OrderBy (n => n.Length)

.Select (n => n.ToUpper());

Its natural linear shape reflects the left-to-right flow of data, as well as keeping lambda expressions alongside their query operators (infix notation). Without extension methods, the query loses its fluency:

IEnumerable<string> query =

Enumerable.Select (

Enumerable.OrderBy (

Enumerable.Where (

names, n => n.Contains ("a")

), n => n.Length

), n => n.ToUpper()

);

Composing Lambda Expressions

In previous examples, we fed the following lambda expression to the Where operator:

n => n.Contains ("a") // Input type=string, return type=bool.

NOTE

A lambda expression that takes a value and returns a bool is called a predicate.

The purpose of the lambda expression depends on the particular query operator. With the Where operator, it indicates whether an element should be included in the output sequence. In the case of the OrderBy operator, the lambda expression maps each element in the input sequence to its sorting key. With the Select operator, the lambda expression determines how each element in the input sequence is transformed before being fed to the output sequence.

NOTE

A lambda expression in a query operator always works on individual elements in the input sequence—not the sequence as a whole.

The query operator evaluates your lambda expression upon demand—typically once per element in the input sequence. Lambda expressions allow you to feed your own logic into the query operators. This makes the query operators versatile—as well as being simple under the hood. Here’s a complete implementation of Enumerable.Where, exception handling aside:

public static IEnumerable<TSource> Where<TSource>

(this IEnumerable<TSource> source, Func<TSource,bool> predicate)

{

foreach (TSource element in source)

if (predicate (element))

yield return element;

}

Lambda expressions and Func signatures

The standard query operators utilize generic Func delegates. Func is a family of general purpose generic delegates in System.Linq, defined with the following intent:

The type arguments in Func appear in the same order they do in lambda expressions.

Hence, Func<TSource,bool> matches a TSource=>bool lambda expression: one that accepts a TSource argument and returns a bool value.

Similarly, Func<TSource,TResult> matches a TSource=>TResult lambda expression.

The Func delegates are listed in the section Lambda Expressions in Chapter 4.

Lambda expressions and element typing

The standard query operators use the following generic type names:

|

Generic type letter |

Meaning |

|

TSource |

Element type for the input sequence |

|

TResult |

Element type for the output sequence—if different from TSource |

|

TKey |

Element type for the key used in sorting, grouping, or joining |

TSource is determined by the input sequence. TResult and TKey are inferred from your lambda expression.

For example, consider the signature of the Select query operator:

public static IEnumerable<TResult> Select<TSource,TResult>

(this IEnumerable<TSource> source, Func<TSource,TResult> selector)

Func<TSource,TResult> matches a TSource=>TResult lambda expression: one that maps an input element to an output element. TSource and TResult are different types, so the lambda expression can change the type of each element. Further, the lambda expression determines the output sequence type. The following query uses Select to transform string type elements to integer type elements:

string[] names = { "Tom", "Dick", "Harry", "Mary", "Jay" };

IEnumerable<int> query = names.Select (n => n.Length);

foreach (int length in query)

Console.Write (length + "|"); // 3|4|5|4|3|

The compiler infers the type of TResult from the return value of the lambda expression. In this case, TResult is inferred to be of type int.

The Where query operator is simpler and requires no type inference for the output, since input and output elements are of the same type. This makes sense because the operator merely filters elements; it does not transform them:

public static IEnumerable<TSource> Where<TSource>

(this IEnumerable<TSource> source, Func<TSource,bool> predicate)

Finally, consider the signature of the OrderBy operator:

// Slightly simplified:

public static IEnumerable<TSource> OrderBy<TSource,TKey>

(this IEnumerable<TSource> source, Func<TSource,TKey> keySelector)

Func<TSource,TKey> maps an input element to a sorting key. TKey is inferred from your lambda expression and is separate from the input and output element types. For instance, we could choose to sort a list of names by length (int key) or alphabetically (string key):

string[] names = { "Tom", "Dick", "Harry", "Mary", "Jay" };

IEnumerable<string> sortedByLength, sortedAlphabetically;

sortedByLength = names.OrderBy (n => n.Length); // int key

sortedAlphabetically = names.OrderBy (n => n); // string key

NOTE

You can call the query operators in Enumerable with traditional delegates that refer to methods instead of lambda expressions. This approach is effective in simplifying certain kinds of local queries—particularly with LINQ to XML—and is demonstrated in Chapter 10. It doesn’t work with IQueryable<T>-based sequences, however (e.g., when querying a database), because the operators in Queryable require lambda expressions in order to emit expression trees. We discuss this later in the section Interpreted Queries.

Natural Ordering

The original ordering of elements within an input sequence is significant in LINQ. Some query operators rely on this behavior, such as Take, Skip, and Reverse.

The Take operator outputs the first x elements, discarding the rest:

int[] numbers = { 10, 9, 8, 7, 6 };

IEnumerable<int> firstThree = numbers.Take (3); // { 10, 9, 8 }

The Skip operator ignores the first x elements and outputs the rest:

IEnumerable<int> lastTwo = numbers.Skip (3); // { 7, 6 }

Reverse does exactly as it says:

IEnumerable<int> reversed = numbers.Reverse(); // { 6, 7, 8, 9, 10 }

With local queries (LINQ-to-objects), operators such as Where and Select preserve the original ordering of the input sequence (as do all other query operators, except for those that specifically change the ordering).

Other Operators

Not all query operators return a sequence. The element operators extract one element from the input sequence; examples are First, Last, and ElementAt:

int[] numbers = { 10, 9, 8, 7, 6 };

int firstNumber = numbers.First(); // 10

int lastNumber = numbers.Last(); // 6

int secondNumber = numbers.ElementAt(1); // 9

int secondLowest = numbers.OrderBy(n=>n).Skip(1).First(); // 7

The aggregation operators return a scalar value; usually of numeric type:

int count = numbers.Count(); // 5;

int min = numbers.Min(); // 6;

The quantifiers return a bool value:

bool hasTheNumberNine = numbers.Contains (9); // true

bool hasMoreThanZeroElements = numbers.Any(); // true

bool hasAnOddElement = numbers.Any (n => n % 2 != 0); // true

Because these operators don’t return a collection, you can’t call further query operators on their result. In other words, they must appear as the last operator in a query.

Some query operators accept two input sequences. Examples are Concat, which appends one sequence to another, and Union, which does the same but with duplicates removed:

int[] seq1 = { 1, 2, 3 };

int[] seq2 = { 3, 4, 5 };

IEnumerable<int> concat = seq1.Concat (seq2); // { 1, 2, 3, 3, 4, 5 }

IEnumerable<int> union = seq1.Union (seq2); // { 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 }

The joining operators also fall into this category. Chapter 9 covers all the query operators in detail.

Query Expressions

C# provides a syntactic shortcut for writing LINQ queries, called query expressions. Contrary to popular belief, a query expression is not a means of embedding SQL into C#. In fact, the design of query expressions was inspired primarily by list comprehensions from functional programming languages such as LISP and Haskell, although SQL had a cosmetic influence.

NOTE

In this book we refer to query expression syntax simply as “query syntax.”

In the preceding section, we wrote a fluent-syntax query to extract strings containing the letter “a”, sorted by length and converted to uppercase. Here’s the same thing in query syntax:

using System;

using System.Collections.Generic;

using System.Linq;

class LinqDemo

{

static void Main()

{

string[] names = { "Tom", "Dick", "Harry", "Mary", "Jay" };

IEnumerable<string> query =

from n in names

where n.Contains ("a") // Filter elements

orderby n.Length // Sort elements

select n.ToUpper(); // Translate each element (project)

foreach (string name in query) Console.WriteLine (name);

}

}

JAY

MARY

HARRY

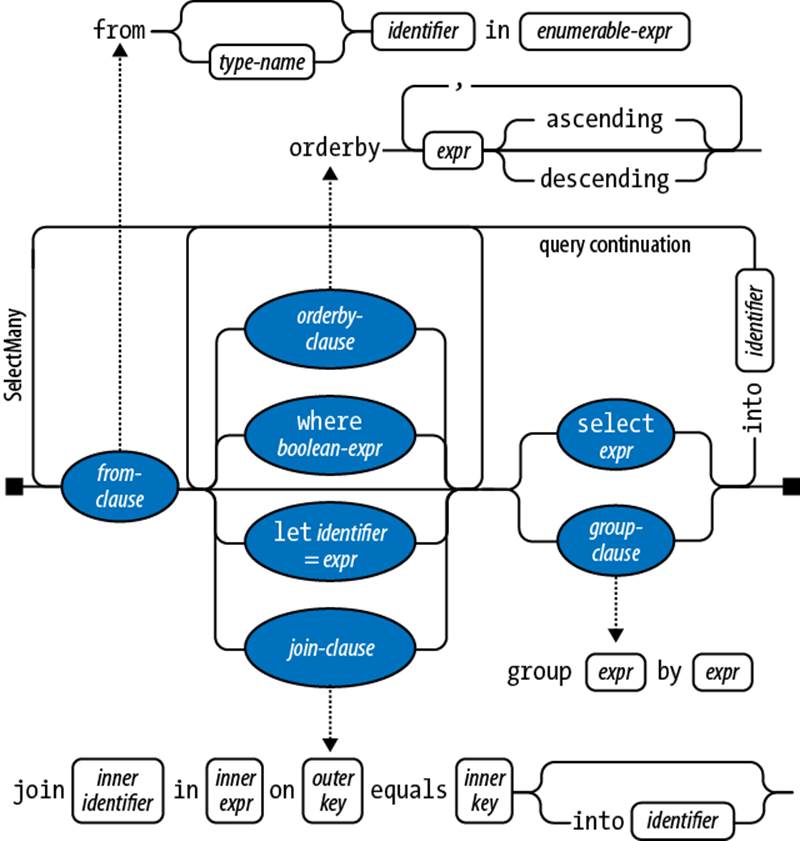

Query expressions always start with a from clause and end with either a select or group clause. The from clause declares a range variable (in this case, n), which you can think of as traversing the input sequence—rather like foreach. Figure 8-2 illustrates the complete syntax as arailroad diagram.

NOTE

To read this diagram, start at the left and then proceed along the track as if you were a train. For instance, after the mandatory from clause, you can optionally include an orderby, where, let or join clause. After that, you can either continue with a select or group clause, or go back and include another from, orderby, where, let or join clause.

Figure 8-2. Query syntax

The compiler processes a query expression by translating it into fluent syntax. It does this in a fairly mechanical fashion—much like it translates foreach statements into calls to GetEnumerator and MoveNext. This means that anything you can write in query syntax you can also write in fluent syntax. The compiler (initially) translates our example query into the following:

IEnumerable<string> query = names.Where (n => n.Contains ("a"))

.OrderBy (n => n.Length)

.Select (n => n.ToUpper());

The Where, OrderBy, and Select operators then resolve using the same rules that would apply if the query were written in fluent syntax. In this case, they bind to extension methods in the Enumerable class, because the System.Linq namespace is imported and names implementsIEnumerable<string>. The compiler doesn’t specifically favor the Enumerable class, however, when translating query expressions. You can think of the compiler as mechanically injecting the words “Where,” “OrderBy,” and “Select” into the statement, and then compiling it as though you’d typed the method names yourself. This offers flexibility in how they resolve. The operators in the database queries that we’ll write in later sections, for instance, will bind instead to extension methods in Queryable.

NOTE

If we remove the using System.Linq directive from our program, the query would not compile, because the Where, OrderBy, and Select methods would have nowhere to bind. Query expressions cannot compile unless you import a namespace (or write an instance method for every query operator!).

Range Variables

The identifier immediately following the from keyword syntax is called the range variable. A range variable refers to the current element in the sequence that the operation is to be performed on.

In our examples, the range variable n appears in every clause in the query. And yet, the variable actually enumerates over a different sequence with each clause:

from n in names // n is our range variable

where n.Contains ("a") // n = directly from the array

orderby n.Length // n = subsequent to being filtered

select n.ToUpper() // n = subsequent to being sorted

This becomes clear when we examine the compiler’s mechanical translation to fluent syntax:

names.Where (n => n.Contains ("a")) // Locally scoped n

.OrderBy (n => n.Length) // Locally scoped n

.Select (n => n.ToUpper()) // Locally scoped n

As you can see, each instance of n is scoped privately to its own lambda expression.

Query expressions also let you introduce new range variables, via the following clauses:

§ let

§ into

§ An additional from clause

§ join

We cover these later in this chapter in the section Composition Strategies, and also in Chapter 9, in the sections Projecting and Joining.

Query Syntax Versus SQL Syntax

Query expressions look superficially like SQL, yet the two are very different. A LINQ query boils down to a C# expression, and so follows standard C# rules. For example, with LINQ, you cannot use a variable before you declare it. In SQL, you reference a table alias in the SELECT clause before defining it in a FROM clause.

A subquery in LINQ is just another C# expression and so requires no special syntax. Subqueries in SQL are subject to special rules.

With LINQ, data logically flows from left to right through the query. With SQL, the order is less well-structured with regard to data flow.

A LINQ query comprises a conveyor belt or pipeline of operators that accept and emit ordered sequences. A SQL query comprises a network of clauses that work mostly with unordered sets.

Query Syntax Versus Fluent Syntax

Query and fluent syntax each have advantages.

Query syntax is simpler for queries that involve any of the following:

§ A let clause for introducing a new variable alongside the range variable

§ SelectMany, Join, or GroupJoin, followed by an outer range variable reference

(We describe the let clause in the later section, Composition Strategies; we describe SelectMany, Join, and GroupJoin in Chapter 9.)

The middle ground is queries that involve the simple use of Where, OrderBy, and Select. Either syntax works well; the choice here is largely personal.

For queries that comprise a single operator, fluent syntax is shorter and less cluttered.

Finally, there are many operators that have no keyword in query syntax. These require that you use fluent syntax—at least in part. This means any operator outside of the following:

Where, Select, SelectMany

OrderBy, ThenBy, OrderByDescending, ThenByDescending

GroupBy, Join, GroupJoin

Mixed Syntax Queries

If a query operator has no query-syntax support, you can mix query syntax and fluent syntax. The only restriction is that each query-syntax component must be complete (i.e., start with a from clause and end with a select or group clause).

Assuming this array declaration:

string[] names = { "Tom", "Dick", "Harry", "Mary", "Jay" };

the following example counts the number of names containing the letter “a”:

int matches = (from n in names where n.Contains ("a") select n).Count();

// 3

The next query obtains the first name in alphabetical order:

string first = (from n in names orderby n select n).First(); // Dick

The mixed syntax approach is sometimes beneficial in more complex queries. With these simple examples, however, we could stick to fluent syntax throughout without penalty:

int matches = names.Where (n => n.Contains ("a")).Count(); // 3

string first = names.OrderBy (n => n).First(); // Dick

NOTE

There are times when mixed syntax queries offer by far the highest “bang for the buck” in terms of function and simplicity. It’s important not to unilaterally favor either query or fluent syntax; otherwise, you’ll be unable to write mixed syntax queries without feeling a sense of failure!

Where applicable, the remainder of this chapter will show key concepts in both fluent and query syntax.

Deferred Execution

An important feature of most query operators is that they execute not when constructed, but when enumerated (in other words, when MoveNext is called on its enumerator). Consider the following query:

var numbers = new List<int>();

numbers.Add (1);

IEnumerable<int> query = numbers.Select (n => n * 10); // Build query

numbers.Add (2); // Sneak in an extra element

foreach (int n in query)

Console.Write (n + "|"); // 10|20|

The extra number that we sneaked into the list after constructing the query is included in the result, because it’s not until the foreach statement runs that any filtering or sorting takes place. This is called deferred or lazy execution and is the same as what happens with delegates:

Action a = () => Console.WriteLine ("Foo");

// We've not written anything to the Console yet. Now let's run it:

a(); // Deferred execution!

All standard query operators provide deferred execution, with the following exceptions:

§ Operators that return a single element or scalar value, such as First or Count

§ The following conversion operators:

ToArray, ToList, ToDictionary, ToLookup

These operators cause immediate query execution because their result types have no mechanism for providing deferred execution. The Count method, for instance, returns a simple integer, which doesn’t then get enumerated. The following query is executed immediately:

int matches = numbers.Where (n => n < 2).Count(); // 1

Deferred execution is important because it decouples query construction from query execution. This allows you to construct a query in several steps, as well as making database queries possible.

NOTE

Subqueries provide another level of indirection. Everything in a subquery is subject to deferred execution—including aggregation and conversion methods. We describe this in the section Subqueries later in this chapter.

Reevaluation

Deferred execution has another consequence: a deferred execution query is reevaluated when you re-enumerate:

var numbers = new List<int>() { 1, 2 };

IEnumerable<int> query = numbers.Select (n => n * 10);

foreach (int n in query) Console.Write (n + "|"); // 10|20|

numbers.Clear();

foreach (int n in query) Console.Write (n + "|"); // <nothing>

There are a couple of reasons why reevaluation is sometimes disadvantageous:

§ Sometimes you want to “freeze” or cache the results at a certain point in time.

§ Some queries are computationally intensive (or rely on querying a remote database), so you don’t want to unnecessarily repeat them.

You can defeat reevaluation by calling a conversion operator, such as ToArray or ToList. ToArray copies the output of a query to an array; ToList copies to a generic List<T>:

var numbers = new List<int>() { 1, 2 };

List<int> timesTen = numbers

.Select (n => n * 10)

.ToList(); // Executes immediately into a List<int>

numbers.Clear();

Console.WriteLine (timesTen.Count); // Still 2

Captured Variables

If your query’s lambda expressions capture outer variables, the query will honor the value of the those variables at the time the query runs:

int[] numbers = { 1, 2 };

int factor = 10;

IEnumerable<int> query = numbers.Select (n => n * factor);

factor = 20;

foreach (int n in query) Console.Write (n + "|"); // 20|40|

This can be a trap when building up a query within a for loop. For example, suppose we wanted to remove all vowels from a string. The following, although inefficient, gives the correct result:

IEnumerable<char> query = "Not what you might expect";

query = query.Where (c => c != 'a');

query = query.Where (c => c != 'e');

query = query.Where (c => c != 'i');

query = query.Where (c => c != 'o');

query = query.Where (c => c != 'u');

foreach (char c in query) Console.Write (c); // Nt wht y mght xpct

Now watch what happens when we refactor this with a for loop:

IEnumerable<char> query = "Not what you might expect";

string vowels = "aeiou";

for (int i = 0; i < vowels.Length; i++)

query = query.Where (c => c != vowels[i]);

foreach (char c in query) Console.Write (c);

An IndexOutOfRangeException is thrown upon enumerating the query, because as we saw in Chapter 4 (see Capturing Outer Variables), the compiler scopes the iteration variable in the for loop as if it was declared outside the loop. Hence each closure captures the same variable (i) whose value is 5 when the query is actually enumerated. To solve this, you must assign the loop variable to another variable declared inside the statement block:

for (int i = 0; i < vowels.Length; i++)

{

char vowel = vowels[i];

query = query.Where (c => c != vowel);

}

This forces a fresh variable to be captured on each loop iteration.

NOTE

In C# 5.0, another way to solve the problem is to replace the for loop with a foreach loop:

foreach (char vowel in vowels)

query = query.Where (c => c != vowel);

This works in C# 5.0 but fails in earlier versions of C# for the reasons we described in Chapter 4.

How Deferred Execution Works

Query operators provide deferred execution by returning decorator sequences.

Unlike a traditional collection class such as an array or linked list, a decorator sequence (in general) has no backing structure of its own to store elements. Instead, it wraps another sequence that you supply at runtime, to which it maintains a permanent dependency. Whenever you request data from a decorator, it in turn must request data from the wrapped input sequence.

NOTE

The query operator’s transformation constitutes the “decoration.” If the output sequence performed no transformation, it would be a proxy rather than a decorator.

Calling Where merely constructs the decorator wrapper sequence, holding a reference to the input sequence, the lambda expression, and any other arguments supplied. The input sequence is enumerated only when the decorator is enumerated.

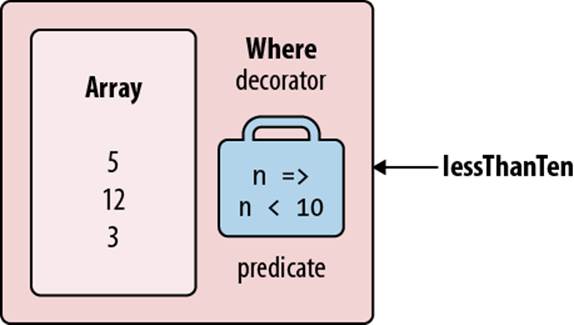

Figure 8-3 illustrates the composition of the following query:

IEnumerable<int> lessThanTen = new int[] { 5, 12, 3 }.Where (n => n < 10);

Figure 8-3. Decorator sequence

When you enumerate lessThanTen, you’re, in effect, querying the array through the Where decorator.

The good news—if you ever want to write your own query operator—is that implementing a decorator sequence is easy with a C# iterator. Here’s how you can write your own Select method:

public static IEnumerable<TResult> Select<TSource,TResult>

(this IEnumerable<TSource> source, Func<TSource,TResult> selector)

{

foreach (TSource element in source)

yield return selector (element);

}

This method is an iterator by virtue of the yield return statement. Functionally, it’s a shortcut for the following:

public static IEnumerable<TResult> Select<TSource,TResult>

(this IEnumerable<TSource> source, Func<TSource,TResult> selector)

{

return new SelectSequence (source, selector);

}

where SelectSequence is a (compiler-written) class whose enumerator encapsulates the logic in the iterator method.

Hence, when you call an operator such as Select or Where, you’re doing nothing more than instantiating an enumerable class that decorates the input sequence.

Chaining Decorators

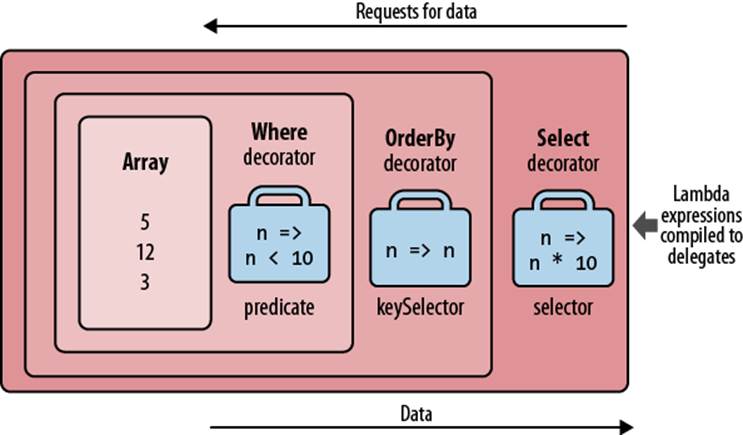

Chaining query operators creates a layering of decorators. Consider the following query:

IEnumerable<int> query = new int[] { 5, 12, 3 }.Where (n => n < 10)

.OrderBy (n => n)

.Select (n => n * 10);

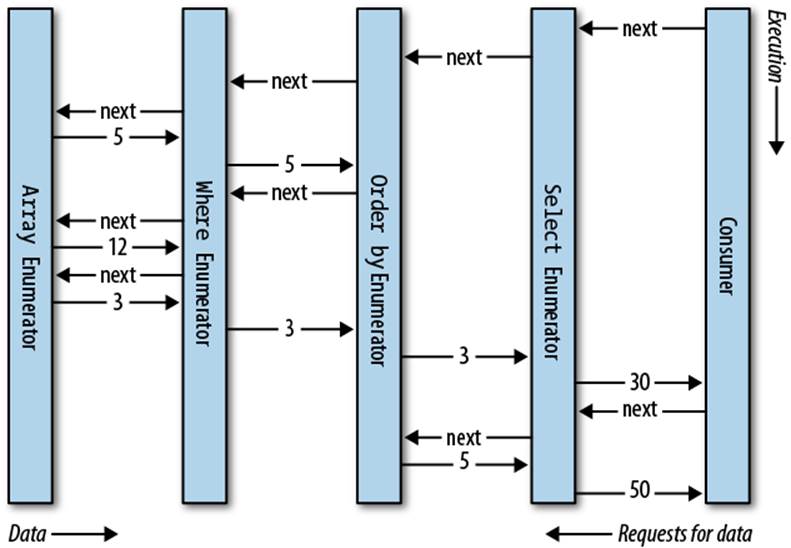

Each query operator instantiates a new decorator that wraps the previous sequence (rather like a Russian nesting doll). The object model of this query is illustrated in Figure 8-4. Note that this object model is fully constructed prior to any enumeration.

Figure 8-4. Layered decorator sequences

When you enumerate query, you’re querying the original array, transformed through a layering or chain of decorators.

NOTE

Adding ToList onto the end of this query would cause the preceding operators to execute right away, collapsing the whole object model into a single list.

Figure 8-5 shows the same object composition in UML syntax. Select’s decorator references the OrderBy decorator, which references Where’s decorator, which references the array. A feature of deferred execution is that you build the identical object model if you compose the query progressively:

Figure 8-5. UML decorator composition

IEnumerable<int>

source = new int[] { 5, 12, 3 },

filtered = source .Where (n => n < 10),

sorted = filtered .OrderBy (n => n),

query = sorted .Select (n => n * 10);

How Queries Are Executed

Here are the results of enumerating the preceding query:

foreach (int n in query) Console.WriteLine (n);

30

50

Behind the scenes, the foreach calls GetEnumerator on Select’s decorator (the last or outermost operator), which kicks everything off. The result is a chain of enumerators that structurally mirrors the chain of decorator sequences. Figure 8-6 illustrates the flow of execution as enumeration proceeds.

Figure 8-6. Execution of a local query

In the first section of this chapter, we depicted a query as a production line of conveyor belts. Extending this analogy, we can say a LINQ query is a lazy production line, where the conveyor belts roll elements only upon demand. Constructing a query constructs a production line—with everything in place—but with nothing rolling. Then when the consumer requests an element (enumerates over the query), the rightmost conveyor belt activates; this in turn triggers the others to roll—as and when input sequence elements are needed. LINQ follows a demand-driven pullmodel, rather than a supply-driven push model. This is important—as we’ll see later—in allowing LINQ to scale to querying SQL databases.

Subqueries

A subquery is a query contained within another query’s lambda expression. The following example uses a subquery to sort musicians by their last name:

string[] musos =

{ "David Gilmour", "Roger Waters", "Rick Wright", "Nick Mason" };

IEnumerable<string> query = musos.OrderBy (m => m.Split().Last());

m.Split converts each string into a collection of words, upon which we then call the Last query operator. m.Split().Last is the subquery; query references the outer query.

Subqueries are permitted because you can put any valid C# expression on the right-hand side of a lambda. A subquery is simply another C# expression. This means that the rules for subqueries are a consequence of the rules for lambda expressions (and the behavior of query operators in general).

NOTE

The term subquery, in the general sense, has a broader meaning. For the purpose of describing LINQ, we use the term only for a query referenced from within the lambda expression of another query. In a query expression, a subquery amounts to a query referenced from an expression in any clause except the from clause.

A subquery is privately scoped to the enclosing expression and is able to reference parameters in the outer lambda expression (or range variables in a query expression).

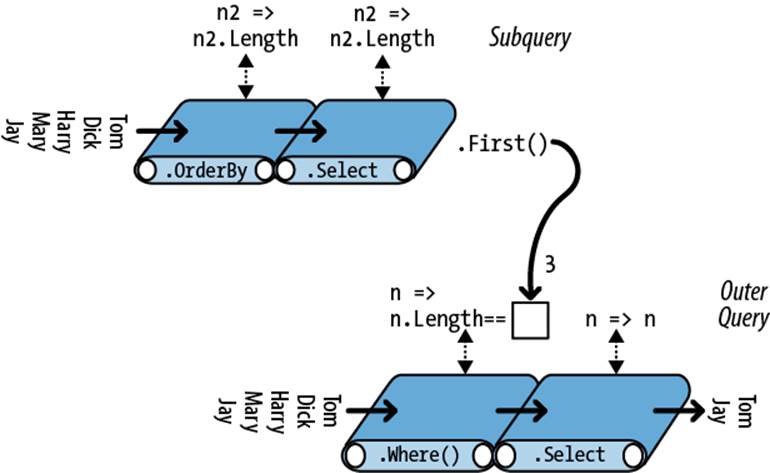

m.Split().Last is a very simple subquery. The next query retrieves all strings in an array whose length matches that of the shortest string:

string[] names = { "Tom", "Dick", "Harry", "Mary", "Jay" };

IEnumerable<string> outerQuery = names

.Where (n => n.Length == names.OrderBy (n2 => n2.Length)

.Select (n2 => n2.Length).First());

Tom, Jay

Here’s the same thing as a query expression:

IEnumerable<string> outerQuery =

from n in names

where n.Length ==

(from n2 in names orderby n2.Length select n2.Length).First()

select n;

Because the outer range variable (n) is in scope for a subquery, we cannot reuse n as the subquery’s range variable.

A subquery is executed whenever the enclosing lambda expression is evaluated. This means a subquery is executed upon demand, at the discretion of the outer query. You could say that execution proceeds from the outside in. Local queries follow this model literally; interpreted queries (e.g., database queries) follow this model conceptually.

The subquery executes as and when required, to feed the outer query. In our example, the subquery (the top conveyor belt in Figure 8-7) executes once for every outer loop iteration. This is illustrated in Figure 8-7 and Figure 8-8.

Figure 8-7. Subquery composition

Figure 8-8. UML subquery composition

We can express our preceding subquery more succinctly as follows:

IEnumerable<string> query =

from n in names

where n.Length == names.OrderBy (n2 => n2.Length).First().Length

select n;

With the Min aggregation function, we can simplify the query further:

IEnumerable<string> query =

from n in names

where n.Length == names.Min (n2 => n2.Length)

select n;

In the later section Interpreted Queries, we’ll describe how remote sources such as SQL tables can be queried. Our example makes an ideal database query, because it would be processed as a unit, requiring only one round trip to the database server. This query, however, is inefficient for a local collection because the subquery is recalculated on each outer loop iteration. We can avoid this inefficiency by running the subquery separately (so that it’s no longer a subquery):

int shortest = names.Min (n => n.Length);

IEnumerable<string> query = from n in names

where n.Length == shortest

select n;

NOTE

Factoring out subqueries in this manner is nearly always desirable when querying local collections. An exception is when the subquery is correlated, meaning that it references the outer range variable. We explore correlated subqueries in Projecting in Chapter 9.

Subqueries and Deferred Execution

An element or aggregation operator such as First or Count in a subquery doesn’t force the outer query into immediate execution—deferred execution still holds for the outer query. This is because subqueries are called indirectly—through a delegate in the case of a local query, or through an expression tree in the case of an interpreted query.

An interesting case arises when you include a subquery within a Select expression. In the case of a local query, you’re actually projecting a sequence of queries—each itself subject to deferred execution. The effect is generally transparent, and it serves to further improve efficiency. We revisit Select subqueries in some detail in Chapter 9.

Composition Strategies

In this section, we describe three strategies for building more complex queries:

§ Progressive query construction

§ Using the into keyword

§ Wrapping queries

All are chaining strategies and produce identical runtime queries.

Progressive Query Building

At the start of the chapter, we demonstrated how you could build a fluent query progressively:

var filtered = names .Where (n => n.Contains ("a"));

var sorted = filtered .OrderBy (n => n);

var query = sorted .Select (n => n.ToUpper());

Because each of the participating query operators returns a decorator sequence, the resultant query is the same chain or layering of decorators that you would get from a single-expression query. There are a couple of potential benefits, however, to building queries progressively:

§ It can make queries easier to write.

§ You can add query operators conditionally. For example:

if (includeFilter) query = query.Where (...)

This is more efficient than:

query = query.Where (n => !includeFilter || <expression>)

because it avoids adding an extra query operator if includeFilter is false.

A progressive approach is often useful in query comprehensions. To illustrate, imagine we want to remove all vowels from a list of names, and then present in alphabetical order those whose length is still more than two characters. In fluent syntax, we could write this query as a single expression—by projecting before we filter:

IEnumerable<string> query = names

.Select (n => n.Replace ("a", "").Replace ("e", "").Replace ("i", "")

.Replace ("o", "").Replace ("u", ""))

.Where (n => n.Length > 2)

.OrderBy (n => n);

RESULT: { "Dck", "Hrry", "Mry" }

NOTE

Rather than calling string’s Replace method five times, we could remove vowels from a string more efficiently with a regular expression:

n => Regex.Replace (n, "[aeiou]", "")

string’s Replace method has the advantage, though, of also working in database queries.

Translating this directly into a query expression is troublesome because the select clause must come after the where and orderby clauses. And if we rearrange the query so as to project last, the result would be different:

IEnumerable<string> query =

from n in names

where n.Length > 2

orderby n

select n.Replace ("a", "").Replace ("e", "").Replace ("i", "")

.Replace ("o", "").Replace ("u", "");

RESULT: { "Dck", "Hrry", "Jy", "Mry", "Tm" }

Fortunately, there are a number of ways to get the original result in query syntax. The first is by querying progressively:

IEnumerable<string> query =

from n in names

select n.Replace ("a", "").Replace ("e", "").Replace ("i", "")

.Replace ("o", "").Replace ("u", "");

query = from n in query where n.Length > 2 orderby n select n;

RESULT: { "Dck", "Hrry", "Mry" }

The into Keyword

NOTE

The into keyword is interpreted in two very different ways by query expressions, depending on context. The meaning we’re describing now is for signaling query continuation (the other is for signaling a GroupJoin).

The into keyword lets you “continue” a query after a projection and is a shortcut for progressively querying. With into, we can rewrite the preceding query as:

IEnumerable<string> query =

from n in names

select n.Replace ("a", "").Replace ("e", "").Replace ("i", "")

.Replace ("o", "").Replace ("u", "")

into noVowel

where noVowel.Length > 2 orderby noVowel select noVowel;

The only place you can use into is after a select or group clause. into “restarts” a query, allowing you to introduce fresh where, orderby, and select clauses.

NOTE

Although it’s easiest to think of into as restarting a query from the perspective of a query expression, it’s all one query when translated to its final fluent form. Hence, there’s no intrinsic performance hit with into. Nor do you lose any points for its use!

The equivalent of into in fluent syntax is simply a longer chain of operators.

Scoping rules

All range variables are out of scope following an into keyword. The following will not compile:

var query =

from n1 in names

select n1.ToUpper()

into n2 // Only n2 is visible from here on.

where n1.Contains ("x") // Illegal: n1 is not in scope.

select n2;

To see why, consider how this maps to fluent syntax:

var query = names

.Select (n1 => n1.ToUpper())

.Where (n2 => n1.Contains ("x")); // Error: n1 no longer in scope

The original name (n1) is lost by the time the Where filter runs. Where’s input sequence contains only uppercase names, so it cannot filter based on n1.

Wrapping Queries

A query built progressively can be formulated into a single statement by wrapping one query around another. In general terms:

var tempQuery = tempQueryExpr

var finalQuery = from ... in tempQuery ...

can be reformulated as:

var finalQuery = from ... in (tempQueryExpr)

Wrapping is semantically identical to progressive query building or using the into keyword (without the intermediate variable). The end result in all cases is a linear chain of query operators. For example, consider the following query:

IEnumerable<string> query =

from n in names

select n.Replace ("a", "").Replace ("e", "").Replace ("i", "")

.Replace ("o", "").Replace ("u", "");

query = from n in query where n.Length > 2 orderby n select n;

Reformulated in wrapped form, it’s the following:

IEnumerable<string> query =

from n1 in

(

from n2 in names

select n2.Replace ("a", "").Replace ("e", "").Replace ("i", "")

.Replace ("o", "").Replace ("u", "")

)

where n1.Length > 2 orderby n1 select n1;

When converted to fluent syntax, the result is the same linear chain of operators as in previous examples.

IEnumerable<string> query = names

.Select (n => n.Replace ("a", "").Replace ("e", "").Replace ("i", "")

.Replace ("o", "").Replace ("u", ""))

.Where (n => n.Length > 2)

.OrderBy (n => n);

(The compiler does not emit the final .Select (n => n) because it’s redundant.)

Wrapped queries can be confusing because they resemble the subqueries we wrote earlier. Both have the concept of an inner and outer query. When converted to fluent syntax, however, you can see that wrapping is simply a strategy for sequentially chaining operators. The end result bears no resemblance to a subquery, which embeds an inner query within the lambda expression of another.

Returning to a previous analogy: when wrapping, the “inner” query amounts to the preceding conveyor belts. In contrast, a subquery rides above a conveyor belt and is activated upon demand through the conveyor belt’s lambda worker (as illustrated in Figure 8-7).

Projection Strategies

Object Initializers

So far, all our select clauses have projected scalar element types. With C# object initializers, you can project into more complex types. For example, suppose, as a first step in a query, we want to strip vowels from a list of names while still retaining the original versions alongside, for the benefit of subsequent queries. We can write the following class to assist:

class TempProjectionItem

{

public string Original; // Original name

public string Vowelless; // Vowel-stripped name

}

and then project into it with object initializers:

string[] names = { "Tom", "Dick", "Harry", "Mary", "Jay" };

IEnumerable<TempProjectionItem> temp =

from n in names

select new TempProjectionItem

{

Original = n,

Vowelless = n.Replace ("a", "").Replace ("e", "").Replace ("i", "")

.Replace ("o", "").Replace ("u", "")

};

The result is of type IEnumerable<TempProjectionItem>, which we can subsequently query:

IEnumerable<string> query = from item in temp

where item.Vowelless.Length > 2

select item.Original;

Dick

Harry

Mary

Anonymous Types

Anonymous types allow you to structure your intermediate results without writing special classes. We can eliminate the TempProjectionItem class in our previous example with anonymous types:

var intermediate = from n in names

select new

{

Original = n,

Vowelless = n.Replace ("a", "").Replace ("e", "").Replace ("i", "")

.Replace ("o", "").Replace ("u", "")

};

IEnumerable<string> query = from item in intermediate

where item.Vowelless.Length > 2

select item.Original;

This gives the same result as the previous example, but without needing to write a one-off class. The compiler does the job instead, writing a temporary class with fields that match the structure of our projection. This means, however, that the intermediate query has the following type:

IEnumerable <random-compiler-produced-name>

The only way we can declare a variable of this type is with the var keyword. In this case, var is more than just a clutter reduction device; it’s a necessity.

We can write the whole query more succinctly with the into keyword:

var query = from n in names

select new

{

Original = n,

Vowelless = n.Replace ("a", "").Replace ("e", "").Replace ("i", "")

.Replace ("o", "").Replace ("u", "")

}

into temp

where temp.Vowelless.Length > 2

select temp.Original;

Query expressions provide a shortcut for writing this kind of query: the let keyword.

The let Keyword

The let keyword introduces a new variable alongside the range variable.

With let, we can write a query extracting strings whose length, excluding vowels, exceeds two characters, as follows:

string[] names = { "Tom", "Dick", "Harry", "Mary", "Jay" };

IEnumerable<string> query =

from n in names

let vowelless = n.Replace ("a", "").Replace ("e", "").Replace ("i", "")

.Replace ("o", "").Replace ("u", "")

where vowelless.Length > 2

orderby vowelless

select n; // Thanks to let, n is still in scope.

The compiler resolves a let clause by projecting into a temporary anonymous type that contains both the range variable and the new expression variable. In other words, the compiler translates this query into the preceding example.

let accomplishes two things:

§ It projects new elements alongside existing elements.

§ It allows an expression to be used repeatedly in a query without being rewritten.

The let approach is particularly advantageous in this example, because it allows the select clause to project either the original name (n) or its vowel-removed version (vowelless).

You can have any number of let statements, before or after a where statement (see Figure 8-2). A let statement can reference variables introduced in earlier let statements (subject to the boundaries imposed by an into clause). let reprojects all existing variables transparently.

A let expression need not evaluate to a scalar type: sometimes it’s useful to have it evaluate to a subsequence, for instance.

Interpreted Queries

LINQ provides two parallel architectures: local queries for local object collections, and interpreted queries for remote data sources. So far, we’ve examined the architecture of local queries, which operate over collections implementing IEnumerable<T>. Local queries resolve to query operators in the Enumerable class, which in turn resolve to chains of decorator sequences. The delegates that they accept—whether expressed in query syntax, fluent syntax, or traditional delegates—are fully local to Intermediate Language (IL) code, just like any other C# method.

By contrast, interpreted queries are descriptive. They operate over sequences that implement IQueryable<T>, and they resolve to the query operators in the Queryable class, which emit expression trees that are interpreted at runtime.

NOTE

The query operators in Enumerable can actually work with IQueryable<T> sequences. The difficulty is that the resultant queries always execute locally on the client—this is why a second set of query operators is provided in the Queryable class.

There are two IQueryable<T> implementations in the .NET Framework:

§ LINQ to SQL

§ Entity Framework (EF)

These LINQ-to-db technologies are very similar in their LINQ support: the LINQ-to-db queries in this book will work with both LINQ to SQL and EF unless otherwise specified.

It’s also possible to generate an IQueryable<T> wrapper around an ordinary enumerable collection by calling the AsQueryable method. We describe AsQueryable in the section Building Query Expressions later in this chapter.

In this section, we’ll use LINQ to SQL to illustrate interpreted query architecture because LINQ to SQL lets us query without having to first write an Entity Data Model. The queries that we write, however, work equally well with Entity Framework (and also many third-party products).

NOTE

IQueryable<T> is an extension of IEnumerable<T> with additional methods for constructing expression trees. Most of the time you can ignore the details of these methods; they’re called indirectly by the Framework. The Building Query Expressions section covers IQueryable<T> in more detail.

Suppose we create a simple customer table in SQL Server and populate it with a few names using the following SQL script:

create table Customer

(

ID int not null primary key,

Name varchar(30)

)

insert Customer values (1, 'Tom')

insert Customer values (2, 'Dick')

insert Customer values (3, 'Harry')

insert Customer values (4, 'Mary')

insert Customer values (5, 'Jay')

With this table in place, we can write an interpreted LINQ query in C# to retrieve customers whose name contains the letter “a” as follows:

using System;

using System.Linq;

using System.Data.Linq; // in System.Data.Linq.dll

using System.Data.Linq.Mapping;

[Table] public class Customer

{

[Column(IsPrimaryKey=true)] public int ID;

[Column] public string Name;

}

class Test

{

static void Main()

{

DataContext dataContext = new DataContext ("connection string");

Table<Customer> customers = dataContext.GetTable <Customer>();

IQueryable<string> query = from c in customers

where c.Name.Contains ("a")

orderby c.Name.Length

select c.Name.ToUpper();

foreach (string name in query) Console.WriteLine (name);

}

}

LINQ to SQL translates this query into the following SQL:

SELECT UPPER([t0].[Name]) AS [value]

FROM [Customer] AS [t0]

WHERE [t0].[Name] LIKE @p0

ORDER BY LEN([t0].[Name])

with the following end result:

JAY

MARY

HARRY

How Interpreted Queries Work

Let’s examine how the preceding query is processed.

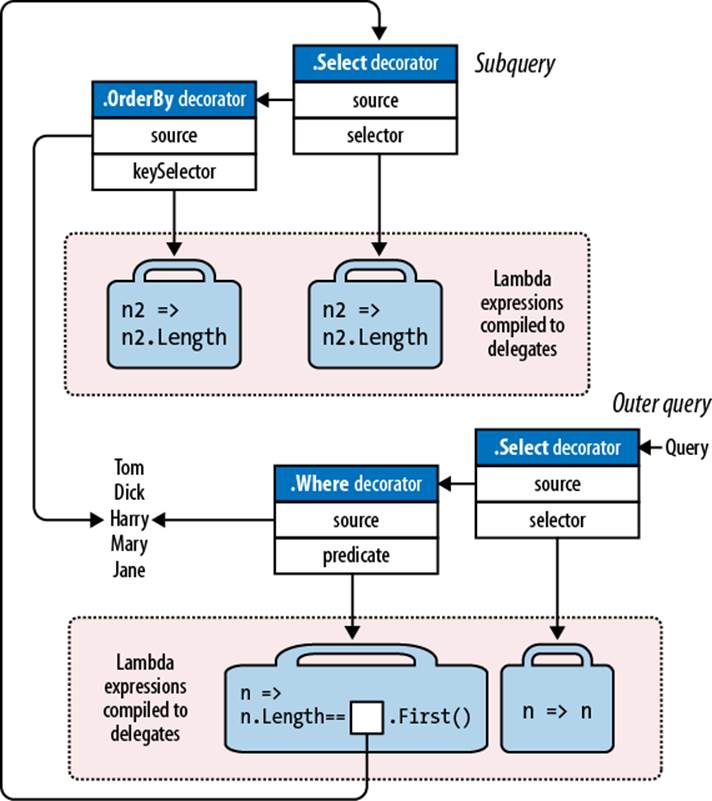

First, the compiler converts query syntax to fluent syntax. This is done exactly as with local queries:

IQueryable<string> query = customers.Where (n => n.Name.Contains ("a"))

.OrderBy (n => n.Name.Length)

.Select (n => n.Name.ToUpper());

Next, the compiler resolves the query operator methods. Here’s where local and interpreted queries differ—interpreted queries resolve to query operators in the Queryable class instead of the Enumerable class.

To see why, we need to look at the customers variable, the source upon which the whole query builds. customers is of type Table<T>, which implements IQueryable<T> (a subtype of IEnumerable<T>). This means the compiler has a choice in resolving Where: it could call the extension method in Enumerable or the following extension method in Queryable:

public static IQueryable<TSource> Where<TSource> (this

IQueryable<TSource> source, Expression <Func<TSource,bool>> predicate)

The compiler chooses Queryable.Where because its signature is a more specific match.

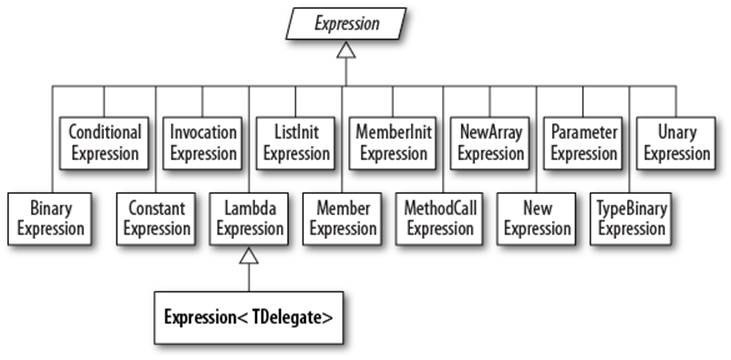

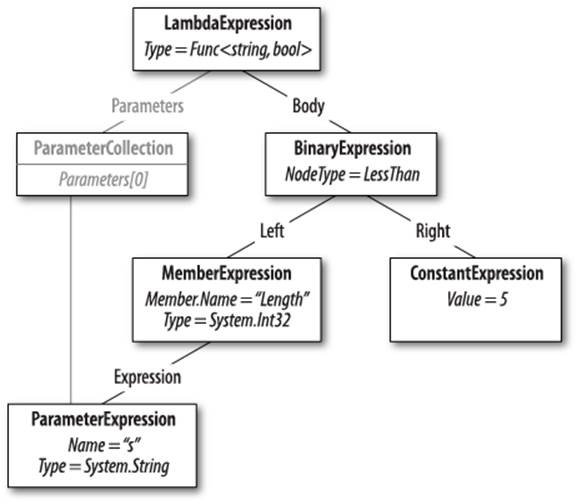

Queryable.Where accepts a predicate wrapped in an Expression<TDelegate> type. This instructs the compiler to translate the supplied lambda expression—in other words, n=>n.Name.Contains("a")—to an expression tree rather than a compiled delegate. An expression tree is an object model based on the types in System.Linq.Expressions that can be inspected at runtime (so that LINQ to SQL or EF can later translate it to a SQL statement).

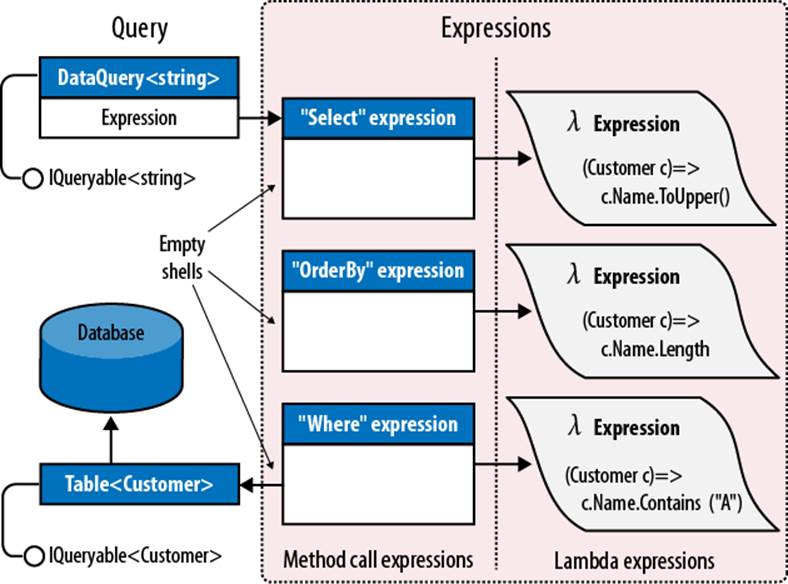

Because Queryable.Where also returns IQueryable<T>, the same process follows with the OrderBy and Select operators. The end result is illustrated in Figure 8-9. In the shaded box, there is an expression tree describing the entire query, which can be traversed at runtime.

Figure 8-9. Interpreted query composition

Execution

Interpreted queries follow a deferred execution model—just like local queries. This means that the SQL statement is not generated until you start enumerating the query. Further, enumerating the same query twice results in the database being queried twice.

Under the covers, interpreted queries differ from local queries in how they execute. When you enumerate over an interpreted query, the outermost sequence runs a program that traverses the entire expression tree, processing it as a unit. In our example, LINQ to SQL translates the expression tree to a SQL statement, which it then executes, yielding the results as a sequence.

NOTE

To work, LINQ to SQL needs some clues as to the schema of the database. The Table and Column attributes that we applied to the Customer class serve just this function. The section LINQ to SQL and Entity Framework, later in this chapter, describes these attributes in more detail. Entity Framework is similar except that it also requires an Entity Data Model (EDM)—an XML file describing the mapping between database and entities.

We said previously that a LINQ query is like a production line. When you enumerate an IQueryable conveyor belt, though, it doesn’t start up the whole production line, like with a local query. Instead, just the IQueryable belt starts up, with a special enumerator that calls upon a production manager. The manager reviews the entire production line—which consists not of compiled code, but of dummies (method call expressions) with instructions pasted to their foreheads (expression trees). The manager then traverses all the expressions, in this case transcribing them to a single piece of paper (a SQL statement), which it then executes, feeding the results back to the consumer. Only one belt turns; the rest of the production line is a network of empty shells, existing just to describe what has to be done.

This has some practical implications. For instance, with local queries, you can write your own query methods (fairly easily, with iterators) and then use them to supplement the predefined set. With remote queries, this is difficult, and even undesirable. If you wrote a MyWhere extension method accepting IQueryable<T>, it would be like putting your own dummy into the production line. The production manager wouldn’t know what to do with your dummy. Even if you intervened at this stage, your solution would be hard-wired to a particular provider, such as LINQ to SQL, and would not work with other IQueryable implementations. Part of the benefit of having a standard set of methods in Queryable is that they define a standard vocabulary for querying any remote collection. As soon as you try to extend the vocabulary, you’re no longer interoperable.

Another consequence of this model is that an IQueryable provider may be unable to cope with some queries—even if you stick to the standard methods. LINQ to SQL and EF are both limited by the capabilities of the database server; some LINQ queries have no SQL translation. If you’re familiar with SQL, you’ll have a good intuition for what these are, although at times you have to experiment to see what causes a runtime error; it can be surprising what does work!

Combining Interpreted and Local Queries

A query can include both interpreted and local operators. A typical pattern is to have the local operators on the outside and the interpreted components on the inside; in other words, the interpreted queries feed the local queries. This pattern works well with LINQ-to-database queries.

For instance, suppose we write a custom extension method to pair up strings in a collection:

public static IEnumerable<string> Pair (this IEnumerable<string> source)

{

string firstHalf = null;

foreach (string element in source)

if (firstHalf == null)

firstHalf = element;

else

{

yield return firstHalf + ", " + element;

firstHalf = null;

}

}

We can use this extension method in a query that mixes LINQ to SQL and local operators:

DataContext dataContext = new DataContext ("connection string");

Table<Customer> customers = dataContext.GetTable <Customer>();

IEnumerable<string> q = customers

.Select (c => c.Name.ToUpper())

.OrderBy (n => n)

.Pair() // Local from this point on.

.Select ((n, i) => "Pair " + i.ToString() + " = " + n);

foreach (string element in q) Console.WriteLine (element);

Pair 0 = HARRY, MARY

Pair 1 = TOM, DICK

Because customers is of a type implementing IQueryable<T>, the Select operator resolves to Queryable.Select. This returns an output sequence also of type IQueryable<T>. But the next query operator, Pair, has no overload accepting IQueryable<T>—only the less specificIEnumerable<T>. So, it resolves to our local Pair method—wrapping the interpreted query in a local query. Pair also emits IEnumerable, so OrderBy wraps another local operator.

On the LINQ to SQL side, the resulting SQL statement is equivalent to:

SELECT UPPER (Name) FROM Customer ORDER BY UPPER (Name)

The remaining work is done locally. In effect, we end up with a local query (on the outside), whose source is an interpreted query (the inside).

AsEnumerable

Enumerable.AsEnumerable is the simplest of all query operators. Here’s its complete definition:

public static IEnumerable<TSource> AsEnumerable<TSource>

(this IEnumerable<TSource> source)

{

return source;

}

Its purpose is to cast an IQueryable<T> sequence to IEnumerable<T>, forcing subsequent query operators to bind to Enumerable operators instead of Queryable operators. This causes the remainder of the query to execute locally.

To illustrate, suppose we had a MedicalArticles table in SQL Server and wanted to use LINQ to SQL or EF to retrieve all articles on influenza whose abstract contained less than 100 words. For the latter predicate, we need a regular expression:

Regex wordCounter = new Regex (@"\b(\w|[-'])+\b");

var query = dataContext.MedicalArticles

.Where (article => article.Topic == "influenza" &&

wordCounter.Matches (article.Abstract).Count < 100);

The problem is that SQL Server doesn’t support regular expressions, so the LINQ-to-db providers will throw an exception, complaining that the query cannot be translated to SQL. We can solve this by querying in two steps: first retrieving all articles on influenza through a LINQ to SQL query, and then filtering locally for abstracts of less than 100 words:

Regex wordCounter = new Regex (@"\b(\w|[-'])+\b");

IEnumerable<MedicalArticle> sqlQuery = dataContext.MedicalArticles

.Where (article => article.Topic == "influenza");

IEnumerable<MedicalArticle> localQuery = sqlQuery

.Where (article => wordCounter.Matches (article.Abstract).Count < 100);

Because sqlQuery is of type IEnumerable<MedicalArticle>, the second query binds to the local query operators, forcing that part of the filtering to run on the client.

With AsEnumerable, we can do the same in a single query:

Regex wordCounter = new Regex (@"\b(\w|[-'])+\b");

var query = dataContext.MedicalArticles

.Where (article => article.Topic == "influenza")

.AsEnumerable()

.Where (article => wordCounter.Matches (article.Abstract).Count < 100);

An alternative to calling AsEnumerable is to call ToArray or ToList. The advantage of AsEnumerable is that it doesn’t force immediate query execution, nor does it create any storage structure.

NOTE

Moving query processing from the database server to the client can hurt performance, especially if it means retrieving more rows. A more efficient (though more complex) way to solve our example would be to use SQL CLR integration to expose a function on the database that implemented the regular expression.

We demonstrate combined interpreted and local queries further in Chapter 10.

LINQ to SQL and Entity Framework

Throughout this and the following chapter, we use LINQ to SQL (L2S) and Entity Framework (EF) to demonstrate interpreted queries. We’ll now examine the key features of these technologies.

NOTE

If you’re already familiar with L2S, take an advance look at Table 8-1 (at end of this section) for a summary of the API differences with respect to querying.

LINQ TO SQL VERSUS ENTITY FRAMEWORK

Both LINQ to SQL and Entity Framework are LINQ-enabled object-relational mappers. The essential difference is that EF allows for stronger decoupling between the database schema and the classes that you query. Instead of querying classes that closely represent the database schema, you query a higher-level abstraction described by an Entity Data Model. This offers extra flexibility, but incurs a cost in both performance and simplicity.

L2S was written by the C# team and was released with Framework 3.5; EF was written by the ADO.NET team and was released later as part of Service Pack 1. L2S has since been taken over by the ADO.NET team. This has resulted in the product receiving only minor subsequent improvements, with the team concentrating more on EF.

EF has improved considerably in later versions, although each technology still has unique strengths. L2S’s strengths are ease of use, simplicity, performance, and the quality of its SQL translations. EF’s strength is its flexibility in creating sophisticated mappings between the database and entity classes. EF also allows for databases other than SQL Server via a provider model (L2S also features a provider model, but this was made internal to encourage third parties to focus on EF instead).

A welcome enhancement in EF 4 is that it supports (almost) the same querying functionality as L2S. This means that the LINQ-to-db queries that we demonstrate in this book work with either technology. Further, it makes L2S excellent for learning how to query databases in LINQ—because it keeps the object-relational side of things simple while you learn querying principles that also work with EF.

LINQ to SQL Entity Classes

L2S allows you to use any class to represent data, as long as you decorate it with appropriate attributes. Here’s a simple example:

[Table]

public class Customer

{

[Column(IsPrimaryKey=true)]

public int ID;

[Column]

public string Name;

}

The [Table] attribute, in the System.Data.Linq.Mapping namespace, tells L2S that an object of this type represents a row in a database table. By default, it assumes the table name matches the class name; if this is not the case, you can specify the table name as follows:

[Table (Name="Customers")]

A class decorated with the [Table] attribute is called an entity in L2S. To be useful, its structure must closely—or exactly—match that of a database table, making it a low-level construct.

The [Column] attribute flags a field or property that maps to a column in a table. If the column name differs from the field or property name, you can specify the column name as follows:

[Column (Name="FullName")]

public string Name;

The IsPrimaryKey property in the [Column] attribute indicates that the column partakes in the table’s primary key and is required for maintaining object identity, as well as allowing updates to be written back to the database.

Instead of defining public fields, you can define public properties in conjunction with private fields. This allows you to write validation logic into the property accessors. If you take this route, you can optionally instruct L2S to bypass your property accessors and write to the field directly when populating from the database:

string _name;

[Column (Storage="_name")]

public string Name { get { return _name; } set { _name = value; } }

Column(Storage="_name") tells L2S to write directly to the _name field (rather than the Name property) when populating the entity. L2S’s use of reflection allows the field to be private—as in this example.

NOTE

You can generate entity classes automatically from a database using either Visual Studio (add a new “LINQ to SQL Classes” project item) or with the SqlMetal command-line tool.

Entity Framework Entity Classes

As with L2S, EF lets you use any class to represent data (although you have to implement special interfaces if you want functionality such as navigation properties).

The following entity class, for instance, represents a customer that ultimately maps to a customer table in the database:

// You'll need to reference System.Data.Entity.dll

[EdmEntityType (NamespaceName = "NutshellModel", Name = "Customer")]

public partial class Customer

{

[EdmScalarPropertyAttribute (EntityKeyProperty = true, IsNullable = false)]

public int ID { get; set; }

[EdmScalarProperty (EntityKeyProperty = false, IsNullable = false)]

public string Name { get; set; }

}

Unlike with L2S, however, a class such as this is not enough on its own. Remember that with EF, you’re not querying the database directly—you’re querying a higher-level model called the Entity Data Model (EDM). There needs to be some way to describe the EDM, and this is most commonly done via an XML file with an .edmx extension, which contains three parts:

§ The conceptual model, which describes the EDM in isolation of the database

§ The store model, which describes the database schema

§ The mapping, which describes how the conceptual model maps to the store

The easiest way to create an .edmx file is to add an “ADO.NET Entity Data Model” project item in Visual Studio and then follow the wizard for generating entities from a database. This creates not only the .edmx file, but the entity classes as well.

NOTE

The entity classes in EF map to the conceptual model. The types that support querying and updating the conceptual model are collectively called Object Services.

The designer assumes that you initially want a simple 1:1 mapping between tables and entities. You can enrich this, however, by tweaking the EDM either with the designer or by editing the underlying .edmx file that it creates for you. Here are some of the things you can do:

§ Map several tables into one entity.

§ Map one table into several entities.

§ Map inherited types to tables using the three standard kinds of strategies popular in the ORM world.

The three kinds of inheritance strategies are:

Table per hierarchy

A single table maps to a whole class hierarchy. The table contains a discriminator column to indicate which type each row should map to.

Table per type

A single table maps to one type, meaning that an inherited type maps to several tables. EF generates a SQL JOIN when you query an entity, to merge all its base types together.

Table per concrete type

A separate table maps to each concrete type. This means that a base type maps to several tables and EF generates a SQL UNION when you query for entities of a base type.

(In contrast, L2S supports only table per hierarchy.)

NOTE

The EDM is complex: a thorough discussion can fill hundreds of pages! A good book that describes this in detail is Julia Lerman’s Programming Entity Framework.

EF also lets you query through the EDM without LINQ—using a textual language called Entity SQL (ESQL). This can be useful for dynamically constructed queries.

DataContext and ObjectContext

Once you’ve defined entity classes (and an EDM in the case of EF) you can start querying. The first step is to instantiate a DataContext (L2S) or ObjectContext (EF), specifying a connection string:

var l2sContext = new DataContext ("database connection string");

var efContext = new ObjectContext ("entity connection string");

NOTE

Instantiating a DataContext/ObjectContext directly is a low-level approach and is good for demonstrating how the classes work. More typically, though, you instantiate a typed context (a subclassed version of these classes), a process we’ll describe shortly.

With L2S, you pass in the database connection string; with EF, you must pass an entity connection string, which incorporates the database connection string plus information on how to find the EDM. (If you’ve created an EDM in Visual Studio, you can find the entity connection string for your EDM in the app.config file.)

You can then obtain a queryable object calling GetTable (L2S) or CreateObjectSet (EF). The following example uses the Customer class that we defined earlier:

var context = new DataContext ("database connection string");

Table<Customer> customers = context.GetTable <Customer>();

Console.WriteLine (customers.Count()); // # of rows in table.

Customer cust = customers.Single (c => c.ID == 2); // Retrieves Customer

// with ID of 2.

Here’s the same thing with EF:

var context = new ObjectContext ("entity connection string");

context.DefaultContainerName = "NutshellEntities";

ObjectSet<Customer> customers = context.CreateObjectSet<Customer>();

Console.WriteLine (customers.Count()); // # of rows in table.

Customer cust = customers.Single (c => c.ID == 2); // Retrieves Customer

// with ID of 2.

NOTE

The Single operator is ideal for retrieving a row by primary key. Unlike First, it throws an exception if more than one element is returned.

A DataContext/ObjectContext object does two things. First, it acts as a factory for generating objects that you can query. Second, it keeps track of any changes that you make to your entities so that you can write them back. We can continue our previous example to update a customer with L2S as follows:

Customer cust = customers.OrderBy (c => c.Name).First();

cust.Name = "Updated Name";

context.SubmitChanges();

With EF, the only difference is that you call SaveChanges instead:

Customer cust = customers.OrderBy (c => c.Name).First();

cust.Name = "Updated Name";

context.SaveChanges();

Typed contexts

Having to call GetTable<Customer>() or CreateObjectSet<Customer>() all the time is awkward. A better approach is to subclass DataContext/ObjectContext for a particular database, adding properties that do this for each entity. This is called a typed context:

class NutshellContext : DataContext // For LINQ to SQL

{

public Table<Customer> Customers

{

get { return GetTable<Customer>(); }

}

// ... and so on, for each table in the database

}

Here’s the same thing for EF:

class NutshellContext : ObjectContext // For Entity Framework

{

public ObjectSet<Customer> Customers

{

get { return CreateObjectSet<Customer>(); }

}

// ... and so on, for each entity in the conceptual model

}

You can then simply do this:

var context = new NutshellContext ("connection string");

Console.WriteLine (context.Customers.Count());

If you use Visual Studio to create a “LINQ to SQL Classes” or “ADO.NET Entity Data Model” project item, it builds a typed context for you automatically. The designers can also do additional work such as pluralizing identifiers—in this example, it’s context.Customers and notcontext.Customer, even though the SQL table and entity class are both called Customer.

DISPOSING DATACONTEXT/OBJECTCONTEXT

Although DataContext/ObjectContext implement IDisposable, you can (in general) get away without disposing instances. Disposing forces the context’s connection to dispose—but this is usually unnecessary because L2S and EF close connections automatically whenever you finish retrieving results from a query.

Disposing a context can actually be problematic because of lazy evaluation. Consider the following:

IQueryable<Customer> GetCustomers (string prefix)

{

using (var dc = new NutshellContext ("connection string"))

return dc.GetTable<Customer>()

.Where (c => c.Name.StartsWith (prefix));

}

...

foreach (Customer c in GetCustomers ("a"))

Console.WriteLine (c.Name);

This will fail because the query is evaluated when we enumerate it—which is after disposing its DataContext.

There are some caveats, though, on not disposing contexts:

§ It relies on the connection object releasing all unmanaged resources on the Close method. While this holds true with SqlConnection, it’s theoretically possible for a third-party connection to keep resources open if you call Close but not Dispose (though this would arguably violate the contract defined by IDbConnection.Close).

§ If you manually call GetEnumerator on a query (instead of using foreach) and then fail to either dispose the enumerator or consume the sequence, the connection will remain open. Disposing the DataContext/ObjectContext provides a backup in such scenarios.

§ Some people feel that it’s tidier to dispose contexts (and all objects that implement IDisposable).

If you want to explicitly dispose contexts, you must pass a DataContext/ObjectContext instance into methods such as GetCustomers to avoid the problem described.

Object tracking