A Theory of Fun for Game Design (2013)

Chapter 9. Games in Context

Game design is becoming a discipline. In the past 10 years there has been a large increase in the number of books about game design, the beginnings of a critical vocabulary, and the creation of academic programs. The field has started to move away from the hit-or-miss shot-in-the-dark approach, and towards an understanding of how games work.

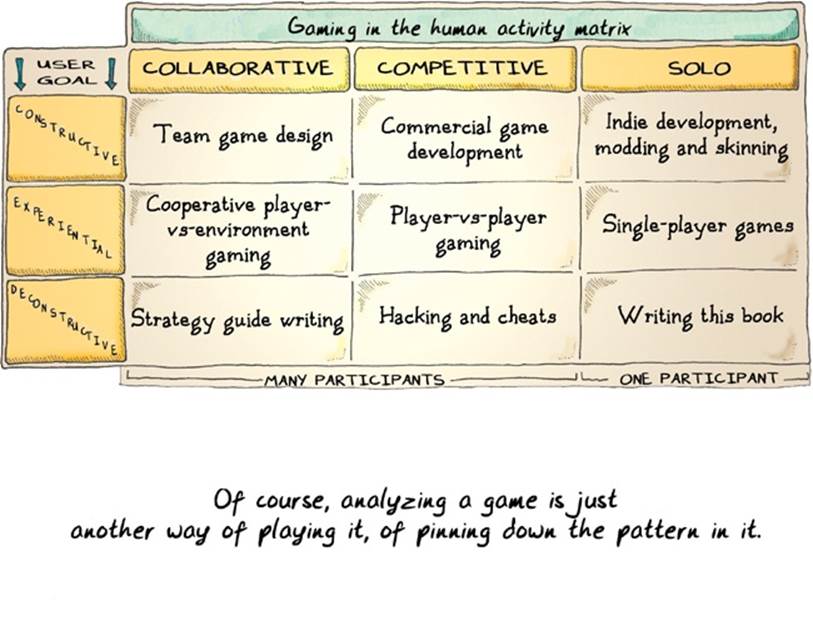

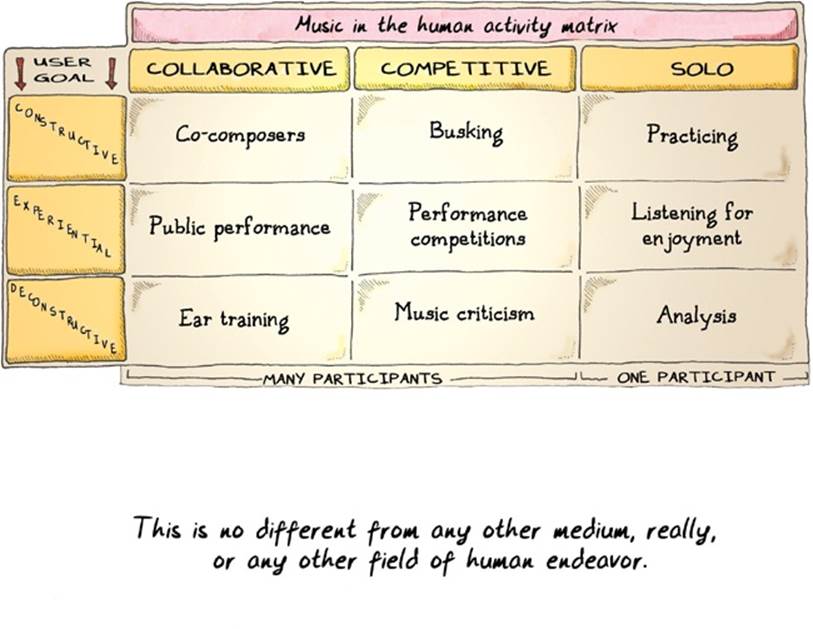

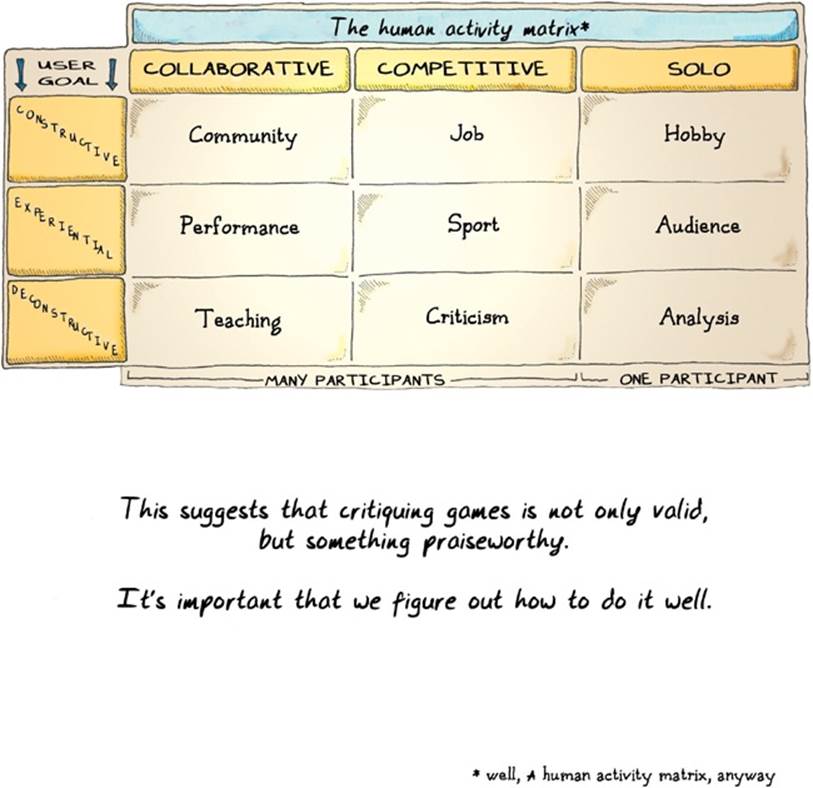

On the facing pages, I’ve filled out a few grids with different human endeavors. This may rub you wrong philosophically. Bear with me—there are two sorts of people in this world, those who divide everyone into two sorts of people and those who don’t.

Any given activity can be performed either by yourself or with others. If you are doing it with others, you can be working either with or against each other. I call these three approaches collaborative, competitive, and solo.

Down the side of our grid, I’ve made a subtler distinction. Are you a passive consumer of this activity (to the degree the activity permits)? An audience member? If you are someone who doesn’t work on the activity, but instead lets the work of others wash over you, we’ll call you interested in the experiential side of the activity—you want the experience.

Are you actually creating the experience? Then you are engaging in a constructive activity. Maybe instead, you are taking the experience apart, to see how it works. I used to label this destructive, but it’s not really; often the original is left behind, intact though somewhat bruised and battered. So perhaps deconstructive is a better term.

My second grid shows how we can analyze music. When I look at the chart for music, what I see is a constellation of music-based entertainment. If I made a similar chart for books, it would cover prose-based entertainment. Basically, this chart can be applied to any medium.

“Game” is a very fuzzy word. A few times in this book I have mentioned game systems as being distinct from games, or as the core element that makes something a game (in some senses). But “game systems” are not a medium. They are, depending on the definition, one use of a medium. The medium is really an unwieldy phrase like “formal abstract models for teaching patterns.” I have taken to calling these “ludic artifacts” to distinguish them from the fuzziness of “game.”* Even though ludic artifacts—like fire drills or CIA model war games of the future of the Middle East—may not necessarily be fun, they still belong on the chart. The fact that they are not fun has more to do with their implementation than with their intrinsic nature.

Interaction happens with all media (at a minimum, we interact by engaging with the work). Actively and constructively interacting with stage-based media is termed “acting” and interacting with prose-based media is termed “writing.” There’s been a lot of discussion in professional video game design circles about “the surrender of authorship” inherent in adding greater flexibility to games and in the “mod” community.* I think the key insight here is that players are simply “interacting with the medium” in a way that isn’t purely experiential.

In other words, modding is just playing the game in another way, sort of like a budding writer might rework plots of characters from other writers into derivative journeyman fiction or into fan fiction. The fact that some forms of interaction are constructive (modding a game), experiential (playing a game), or deconstructive (hacking a game) is immaterial; the same activities are possible with a given play, book, or song. Arguably, the act of literary analysis is much the same as the act of hacking a game—the act of disassembling the components of a given piece of work in a medium to see how it works, or even to get it to do things, carry messages, or otherwise represent itself as something other than what the author of the piece intended.

Some of the activities on the first chart aren’t what you would normally term “fun,” even though they are almost all activities in which you learn patterns. We can sit here and debate whether performing music, writing a story, or drawing a picture is fun. Having training in all three, I can tell you that they are all hard work, which isn’t something we necessarily consider fun. But I derive great fulfillment from these activities. This is perhaps analogous to watching Hamlet on stage, reading Lord Jim,* or viewing Guernica*—an interaction with a system rich and challenging enough to permit me to treat it as a learning opportunity.

The chills that go down your back are not always indicative of something that you find enjoyable. A tragedy or moment of great sorrow can cause them. The moment you recognize a pattern, your body will give you the chill as a sign. Just as writing isn’t necessarily fun but might be something valuable for the writer to do, or practicing piano for hours on end might not be fun but something that gives fulfillment, engaging in interaction with games need not be fun, either, but might indeed be fulfilling, thought-provoking, challenging, and also difficult, painful, and even compulsive.

In other words, games can take forms we don’t recognize. They might not be limited to being “a game” or even a “software toy.”* The definition of “game” implies certain things, as do the words “toy,” “sport,” and “hobby.” The layman’s definition of “game” covers only some of the boxes in the grid. Arguably, all of the boxes in the grid are fun to someone. We need to start thinking of games a little more broadly. Otherwise, we will be missing out on large chunks of their potential as a medium.

The reason why the rise of critique and academia surrounding games is important is that it finally adds the missing element to put games in context with the rest of human endeavor. It signals their arrival as a medium. Considering how long they have been around, they’re a little late to the party.

Once games are seen as a medium, we can start worrying about whether they are a medium that permits art. All other media do, after all.

Pinning art down is tricky. We can start from the basics, though. What is art for? Communicating. That’s intrinsic to the definition. And (if you’ve bought into the premises of this book) we have seen that the basic intent of games is rather communicative as well—it is the creation of a symbolic logic set that conveys meaning.

Some apologists for games like to tout the fact that games are interactive as a sign that they are special. Others like to say that interactivity is precisely why games cannot be art, because art relies on authorial intent and control. Both positions are balderdash. Every medium is interactive*—just go look on the grid.

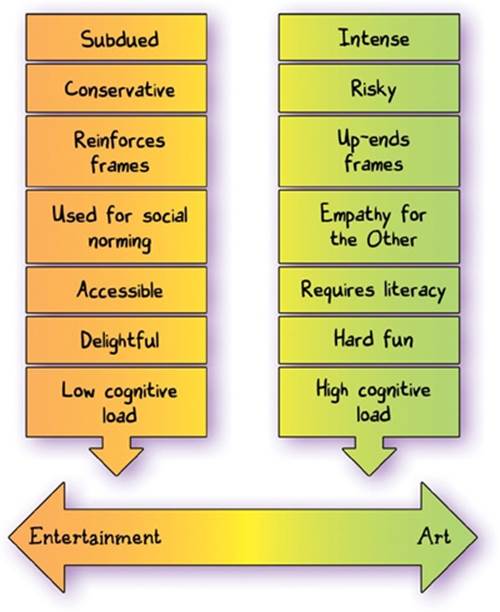

So what is art? My take on it is simple. Media provide information. Entertainment provides comforting, simplistic information. And art provides challenging information, stuff that you have to think about in order to absorb. Art uses a particular medium to communicate within the constraints of that medium, and often what is communicated is thoughts about the medium itself (in other words, a formalist approach to arts—much modern art falls in this category).

The medium shapes the nature of the message, of course, but the message can be representational, impressionistic, narrative, emotional, intellectual, or whatever else. Some art works are solo creations, and some are collaborative (and they can all be made collaborative to an extent, I believe). And some media are actually the result of the collaboration of specialists in many different media, working together to present a work that is incomplete without the use of multiple media within it. Film is one such medium. And games are another.

One of the most common points I hear about why video games are not an art form is that they are just for fun. They are just entertainment. Hopefully, I’ve made it clear why that is a dangerous underestimation of fun. But most music is also just entertainment, and most novels are read just for fun, and most movies are mere escapism, and yes, even most pretty pictures are just pretty pictures. The fact that most games are merely entertainment does not mean that this is all they are doomed to be.

Mere entertainment becomes art when the communicative element in the work is either novel or exceptionally well done. It really is that simple. The work has the power to alter how people perceive the world around them. And it’s hard to imagine a medium more powerful in that regard than video games, where you are presented with a virtual world that reacts to your choices.

“Well done” and “novel” mean, basically, craft. You can have well-crafted entertainment that fails to reach the level of art. The upper reaches of art are usually subtler achievements. They are works that you can return to again and again, and still learn something new from. The analogy for a game would be one you can replay over and over again, and still discover new things.

Since games are closed formal systems, that might mean that games can never be art in that sense. But I don’t think so. I think that means that we just need to decide what we want to say with a given game—something big, something complex, something open to interpretation, something where there is no single right answer—and then make sure that when the player interacts with it, she can come to it again and reveal whole new aspects to the challenge presented.

What would a game like this be?

It would be thought-provoking.

It would be revelatory.

It might contribute to the betterment of society.

It would force us to reexamine assumptions.

It would give us different experiences each time we tried it.

It would allow each of us to approach it in our own ways.

It would forgive misinterpretation—in fact, it might even encourage it.

It would not dictate.

It would immerse, and change a worldview.

Some might say that abstract formal systems cannot achieve this. But I have seen wind course across the sky, bearing leaves; I have seen paintings by Mondrian made of nothing but colored squares;* I have heard Bach played on a harpsichord; I have traced the rhythms of a sonnet; I have followed the steps of a dance.

All media are abstract, formal systems. They have grammars, methods, and systems of craft. They follow rules, whether it is the rules of language, the rules of leading tones in music,* or the rules of visual composition. They often play with these rules and reveal startling new aspects to them.

All artists choose constraints when they set out to create: a postage stamp of paper or a broad canvas; to use rhyme or free verse; the choice of piano versus guitar. In fact, choosing constraints is one of the most fruitful ways to prod creativity.

Games, too, share these characteristics. “Create a one button game.” “Invent a game using nothing more than pennies and a deck of cards.” “Design a game that is about exact cover.”*

Let’s not sell abstraction and formality short.

In fact, the toughest puzzles are the ones that force the most self-examination. They are the ones that challenge us most deeply on many levels—mental stamina, mental agility, creativity, perseverance, physical endurance, and emotional self-abnegation. They come precisely from the interactive portions of the chart, when you look at other media.

Consider the act of creation.

It’s one of the toughest things to do well in human endeavor. And yet it is also one of our most instinctive actions; from a young age, we not only trace patterns but attempt to create new ones. We scribble with crayons, we ba-ba-ba our way through songs.

The fact that playing games—good ones, anyway—is fundamentally a creative act is something that speaks very well for the medium. Games, at their best, are not prescriptive. They demand that the user create a response given the tools at hand. It is a lot easier to fail to respond to a painting than to fail to respond to a game.

No other artistic medium is defined around a single intended effect on the user, such as “fun.” They all embrace a wider array of emotional impact. Now, we may be running into definitional questions for the word “fun” here, obviously, but even so, I’d prefer to approach things from a more formalist* perspective to actually arrive at what the basic building blocks of the medium are. From a formalist point of view, music can be considered ordered sound and silence, poetry can be considered the placement of words and gaps between words, and so on.

The closer we get to understanding the basic building blocks of games—the things that players and creators alike manipulate in interacting with the medium—the more likely we are to achieve the heights of art.

Some folks disagree with me pretty vehemently on this.* They feel that the art of the game lies in the formal construction of systems. The more artfully constructed the system is, the closer the game is to art.

Putting games in context with other media demands that we consider this viewpoint. In literature, it’s called a belles-lettristic* point of view. The beauty of poetry lies solely in the sound and not in the sense, according to those who feel this way.

And yet, even the shape of the sound can be put in context. Let’s digress and consider some other media...

Impressionist* painting is about a more distanced form of seeing, of mimesis. Modern image processing tools describe the formal process used by Impressionist painters (and indeed many of the later processes such as posterization*) as filters. Impressionist paintings are depictions not of an object or a scene, but of the play of light on an object or scene. An Impressionist painting still conforms to all previously established rules of composition—color weight, balance, vanishing point, center of gravity, eye center, and so on—while essentially avoiding painting the object or scene itself, which ends up being absent from the finished work.

Impressionist music was based primarily on repetition; it went on to influence minimalist styles ranging from Philip Glass to electronica. Impressionist music is essentially that of Debussy:* intensely varied in orchestration, extremely complex, particularly in its chromatic harmonies, and very repetitive melodically. Ravel’s work as an orchestrator* is perhaps the epitome of the Impressionistic style: his “Bolero” consists of the same passage played over and over, identical harmonically and melodically; it has merely been orchestrated differently at each repetition, and the dynamics are different. The sense of crescendo throughout the piece is achieved precisely though this repetition.

And of course, there was “Impressionist” writing. Virginia Woolf,* Gertrude Stein,* and many other writers worked with the idea that characters are unknowable. Books like Jacob’s Room and The Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas play with the established notions of self and work towards a realization that other people are essentially unknowable. However, they also propose an alternate notion of knowability: that of “negative space,” whereby a form is understood and its nature grasped by observing the perturbations around it. The term is from the world of pictorial art, which provides many useful insights when discussing the problem of representation of reality.

All of these are organized around the same principles: negative space, embellishing the space around a central theme, and observing perturbations and reflections. There was a zeitgeist at that time;* these approaches were “in the air,” but there was also conscious borrowing from art form to art form. This occurred in large part because no art form stands alone; they bleed into one another.

Can you make an Impressionist game? A game where the formal system conveys the following:

§ The object you seek to understand is not visible or depicted.

§ Negative space is more important than shape.

§ Repetition with variation is central to understanding.

The answer is: of course you can. It’s called Minesweeper.*

In the end, the endeavor that games engage in is similar to the endeavors of any other art form. The principal difference is not the fact that they consist of formal systems. Look at the following lists of terms:

§ Meter, rhyme, spondee, slant rhyme, onomatopoeia, caesura, iamb, trochee, pentameter, rondel, sonnet, verse

§ Phoneme, sentence, accent, fricative, word, clause, object, subject, punctuation, case, pluperfect, tense

§ Meter, fermata, key, note, tempo, coloratura, orchestration, arrangement, scale, mode

§ Color, line, weight, balance, compound, multiply, additive, refraction, closure, model, still life, perspective

§ Rule, level, score, opponent, boss, life, power-up, pick-up, bonus round, icon, unit, counter, board

Let’s not kid ourselves—the sonnet is caged about with as many formal systems as a game is.

If anything, the great irony about games, put in context with other media, is that they may afford less scope to the designer, who has less freedom to impose, less freedom to propagandize. Game systems are not good at conveying specifics, only generalities. It is easy to make a game system that tells you that small groups can prevail over large ones, or the converse. And that may be a valuable and deeply personal statement to make. It’s a lot harder to make an abstract ludic artifact that conveys the specific struggle of a group of World War II soldiers to rescue one other man from behind enemy lines, as the film Saving Private Ryan does, without resorting to the tools of writing. The designer who wants to use game system design as an expressive medium must be like the painter and the musician and the writer, in that she must learn what the strengths of the medium are, and what messages are best conveyed by it.