Games, Design and Play: A detailed approach to iterative game design (2016)

Part I: Concepts

Chapter 1: Games, Design and Play

Chapter 1: Games, Design and Play

![]() Chapter 2: Basic Game Design Tools

Chapter 2: Basic Game Design Tools

![]() Chapter 3: The Kinds of Play

Chapter 3: The Kinds of Play

![]() Chapter 4: The Player Experience

Chapter 4: The Player Experience

Chapter 1. Games, Design and Play

The first step in learning any medium is understanding its basic elements. In this chapter, we begin taking games apart to see how they work. We identify the six basic elements of play design: actions, goals, rules, objects, playspace, and players.

When we talk about playing games, we often talk about them in the same way we do movies, books, and music—as a form of mass media. This isn’t a surprise—since the rise of the Magnavox Odyssey, Pong, and the Atari VCS in the 1970s, games have often been treated as simply another kind of entertainment media. And videogames are the same in many ways—we learn about, purchase, and experience games in quite similar ways to movies, music, even books. But just because games are packaged, marketed, and sold like the products of other mediums doesn’t mean they are conceived of, designed, and produced the same way.

Let’s look past the marketing and distribution to the actual experience videogames provide—play. But what does that mean, to play a videogame? Is it like playing a movie? When you play a movie, you are watching a series of prerecorded images and sounds. You may interpret a movie differently when you watch it multiple times, or you may notice different shots, characters, settings, or plot elements, but the movie itself doesn’t change. But when we play a game, we aren’t just watching, reading, and listening (though we do these things while playing). With games, players have to interact, to be involved, for the game to happen.

This sounds more like playing music—as in performing it, not listening to it. Musicians play music by following the notes the composer wrote.1 In games, players do something similar—they follow the rules written by the game’s designer. So playing music and playing games are a little more alike. When playing music, you are following a score. In the same way a musician will interpret a score and make it their own, players interpret and act inside a game’s rules. There is one big difference between music and games, though—games change based on player input in ways that music does not. In most cases, a music score is static, but a game will change based on what the player does. And as a result, gameplay experiences can be different almost every time, sometimes in big ways, sometimes in ways that are barely perceptible.

1 anna anthropy draws a similar analogy in Chapter 3 of her book, Rise of the Videogame Zinesters: How Freaks, Normals, Amateurs, Artists, Dreamers, Drop-outs, Queers, Housewives, and People Like You Are Taking Back an Art Form, using theater and the performance of a script.

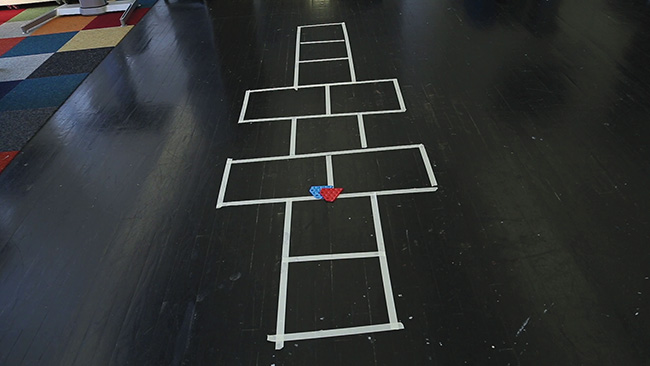

When we talk about playing games, we are talking about players taking an active role that has an impact on the substance and quality of the play experience. In fact, you might say that a game doesn’t take form until it is played. Take the game hopscotch (see Figure 1.1). By itself, it is at most some lines on the ground and a rock or marker of some sort. But add a set of rules and a couple of players, and it turns into a mechanism for generating play. The drawn lines and the rock are explained in the rules, outlining how players jump and throw the rock to see if they can hop through the environment defined by the lines.

Figure 1.1 A hopscotch board.

This is how games work. The game itself is a process that produces play when interacted with. Though we often think of games as being like movies, comics, and music—art and entertainment media—they are also like pocket knives, printing presses, and car engines. By this we mean that games are put into motion by players in the same way these devices are; a pocket knife won’t do much but sit there until someone picks it up and uses the little scissors to trim a thread.

Thinking of games as machines is a systems dynamics approach to game design—considering how the elements in a game come together to create different dynamics. To get a better understanding of this, consider a familiar machine—a car. A car as a system has objects (steering wheel, turn signal, gas pedal) and dynamics (steer, signal, accelerate) that connect and interact to make the car work. The relationships between these elements—their dynamics, the inputs, and the different outputs they create—come together to create the experience that is driving. A car can be operated in many ways. It may have different types of inputs, such as the driver—a race car driver, a student driver, a London taxi driver. Other inputs come from the environmental conditions, the quality of the road, or other cars and pedestrians. (Let’s hope not as a collision!) Depending on these inputs, the car may be operated differently and result in different types of outputs. A fast and wild ride on a racetrack, an awkward parallel parking job, a slow trip in rush hour traffic. And that’s just one type of system. There are many, from cars to computers to coffeemakers, each with its purposes, styles, and outputs.

Instead of focusing on the stuff in the world, systems dynamics suggests we should look at the actions and the interactions between the stuff. Systems are made up of objects, which have relationships to one another, all of which are driven by a function or a goal.2 A game is a kind of system. It takes inputs and generates different kinds of outputs. The elements of the game interact and produce different dynamics. In the case of hopscotch, the game’s design crafts relationships between the drawn lines, the rock players throw, and the rules that enable play. This structure is created by the game’s designer (or designers in many cases, but we will get to that in Chapter 8, “Collaboration and Teamwork”). Without the game design, the rock and lines are just that—a rock and some lines. They are given meaning and purpose through the act of crafting the rules and the configuration of the rock and the lines—in other words, the act of game design. It’s the players that ultimately make the game come to life, just as the interactions between things in the world create the situations and events we live with. When viewing things through the lens of systems, attention gets paid to not just the things, but the dynamic relationships between them and what happens when they interact. And it is the players that determine the purpose of their play experience. Players might play hopscotch in order to move through the game the most quickly, or to play with a flair that prioritizes style over speed. Or maybe they are playing simply as a way to pass the time.

2 For more on systems dynamics, check out Donella Meadows’ excellent Thinking in Systems: A Primer.

This is one of the ways we can think about games: games are systems that dynamically generate play. Fast play, funny play, silly play, serious play, expressive play, reflective play, competitive play, cooperative play—you name a kind of physical, intellectual, and emotional response, and there are games that produce it through play. This is true of all sorts of games, no matter what they are—cardgames, boardgames, text adventures, mobile games, sports, 3D games, and on and on.

While games are systems from the vantage point of systems thinking, they are also works created to express, convey, and provide experiences. Games are just as much about expression and experience as any other medium. This suggests another way to approach games—as a form of expression closer to poetry, literature, and art than to pocket knives and steam engines. Games have style—visual, aural, written, experiential—and they create emotional responses and experiences for players to reflect upon. We want to understand games as things that generate experiences and different dynamics—in a word, play. Hopscotch is illustrative: the system is composed of a few simple rules, chalk and a rock produce exceptional experiences—jumping, laughing, focused concentration, opportunities for performance, competition, fellowship, and any number of other outcomes we wouldn’t expect from such basic materials.

This is the real power of game design—creating play experiences that can entertain, express, connect, cause reflection, and many other kinds of thought and emotion. Part of what makes game design so much fun, but also makes it so challenging, is that the game designer designs something—a game—that produces something else—play. That play, in turn, generates physical, intellectual, and emotional responses. These responses can only be seen when the parts of the machine are assembled and the play begins. And so in this book, we hope to explore how game design is the design of play by keeping in mind how games generate play and how play in turn creates experience and meaning.

The Basic Elements of Play Design

To begin understanding how games work as designed systems for generating play, we need to identify the basic elements from which games are made. The problem is, the parts differ from game to game in pretty drastic ways. Even more perplexing, many of the parts are hidden from us or take an intangible form. For example, a car engine (at least a classic car engine) can be taken apart and understood by looking at the parts and how they operate in relation to one another. On the other hand, a transistor radio is a bit more difficult to decipher by just looking at its component parts. However, when we play with a transistor radio, we get a pretty good sense of what it does, at least at a higher level. When we turn the tuning knob, we find radio stations at different frequencies. Move the antenna, and we pick them up more or less clearly. We can adjust the volume. And when we move to a different city, we receive different stations. Looking at the insides of the radio might not tell us much about what this machine does, but fiddling around with it helps us understand how it works and might even reveal other things related to it, such as the properties of radio waves.

Some games are easy to take apart and see what’s there (car engines), and some are more mysterious (radios). However, despite the many differences in games, we can identify the six basic elements in games: actions, goals, rules, objects, playspaces, and players. Rather than get too far into the invisible realm of games, let’s look at a game with most of its elements visible for us to see: football, or as we call it in the United States, soccer (see Figure 1.2).

Figure 1.2 A soccer game.

The best place to start is with actions, as this is the most obvious designed aspect of a game. Actions are the things players get to do while playing a game. The main actions in soccer are kicking the ball and running on the field (see Figure 1.2). These two core actions combine in interesting ways as the teams try to get the ball in the other team’s goal. Around them emerge other actions, like dribbling the ball or passing it from player to player.

What lets players know what actions they can perform? The rules define what players are able to do—moving the ball with their feet, trying to get the ball inside the net, playing within a limited period of time, and so on. A game’s rules are equally concerned with what players cannot do. With soccer, the most important limitation is banning the use of hands by all players but the goalkeepers. In this respect, the rules governing actions in games are about both permitting and limiting. Rules are the invisible structure that holds a game together. We can’t see the rules of soccer without checking a rules book, yet they are always present, defining the play experience.

In games, rules are a source of player creativity, choice, and expression. This might seem paradoxical because in most cases we think of rules as limiting what we can do. However, the restrictions rules place upon players are also what make games fun. Rules give us opportunities to try new things, develop strategies, and find enjoyment within a play experience. Think of a fantastic moment in a soccer game you’ve watched or played—an amazing bicycle kick, or a well-timed tackle to stop an attempt to score, a kick that gracefully arcs into the net. These are only possible because of the rules of the game.

That brings us to next basic element of games: goals. A game’s goal defines what players try to achieve while playing. The actions and rules of a game make more sense when we know the game’s goal. If soccer didn’t have the stated goal of score the most goals in the allotted period of time, what would the players do? Just kick the ball back and forth? More than likely, the players would make up their own goals to give structure to their play. This is what separates games from toys.3 By itself, outside the rules of the game, a soccer ball is a toy. We can do whatever we want with it—throw it, kick it, draw a face on it even. But inside a game, the ball and everything else take on special meaning. Sometimes this meaning is to win, as in competitive soccer, but sometimes it is simply to spend time with friends and family during a backyard soccer game. In other cases, the goal is much more self-directed, like trying to make a character in The Sims rich and famous or building a replica of the Taj Mahal inside Minecraft. In other cases, the goal is simply the experience of the game, like in Mattie Brice’s Mainichi, a game created to provide a window into daily life.

3 The difference between games and toys (among other things) is thoughtfully described in Greg Costikyan’s 1994 essay “I Have No Words & I Must Design” from the British role-playing journal Interactive Fantasy.

Without the ball, soccer players would just be running around, and without the two nets, they wouldn’t have a location for attempting to kick the ball or to keep the ball out of. This brings us to the fourth basic element of games: objects. Objects are the things players interact with during play. There are two types of objects in soccer—the ball and the two nets at either end of the field. In some games, resources are also objects in the game—such as Monopoly money or the amount of health a videogame character has. To put these objects into use and to help create physical and conceptual relationships between them, there needs to be a playspace. In the case of soccer, this is the field, the defined area within which the game takes place and the objects are located. Together, the objects and the playspace constitute the main physical, tangible elements of a game. Objects are defined by a game’s rules and are necessary for the game to happen.

The last basic element of games is the players. They are part of the game’s design, too, right? Without players, the ball and nets just sit there on the field, and the rules are just words on a page. Players put the game that is soccer into motion through their pursuit of the goals using actions and objects within the playspace, all governed by the game’s rules. Players are the most important part of any game, as they are the operator that makes the game go.

We now have a working list of the “moving parts” of games and play experiences: actions, goals, rules, objects, playspace, and players. Together, these constitute the basic elements of game design.

From Six Elements, Limitless Play Experiences

Crafting the basic elements of the actions, goals, rules, objects, and playspace and how they come together to create play—that’s the role of the game designer. You make decisions about what kind of play experience you want players to have, and you then design a game that will give players that kind of experience.

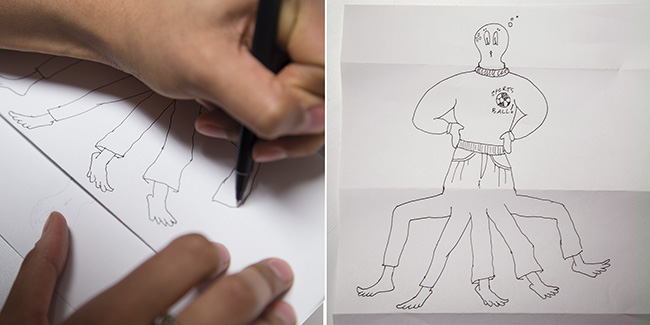

Of course, not all games combine these elements in the same way. Take the goals of a game. In soccer, the goal is to be the team with the most points when time runs out. This drives the entire experience, at least in competitive matches, putting everything else about the game in service of this goal. But in a game like Exquisite Corpse (see Figure 1.3), the goal is to have an experience rather than to compete. Exquisite Corpse begins with a folded sheet of paper. The first player draws on one of the surfaces, making sure her drawing slightly overlaps the adjacent panels. The paper is then refolded so the next player has one of the mostly blank panels. Play continues until all panels are drawn upon. The paper is then unfolded, and the players see the image they collaboratively created. In the case of Exquisite Corpse, there is a goal that shapes the play experience but in a less heavy-handed way. There’s no score in Exquisite Corpse and no points to count. The goal is to create a drawing together. So a goal can be the driving reason to play, as in soccer, or simply a catalyst for a playful experience, like in Exquisite Corpse.

Figure 1.3 An Exquisite Corpse drawing.

Playspaces can take many forms as well, depending on the intended play experience. The fields of sports, the materials of boardgames, the fantastic environments of 3D videogames, the graph paper of tabletop role-playing games—these are just a few of the kinds of playspaces our games can use. The playspace of a game should be designed to encourage and support the kind of play experience you want your players to have. If you want a playspace that is mostly in the player’s imagination, you might consider a simple, abstract map for tracking players’ collective discoveries. If you want to provide players with a rich story world of your own design, you might consider a more detailed 3D game.

The actions performed while playing a game can vary wildly, too, from game to game. The most typical action of videogames is shooting. But really, if we look more closely, the actions are much more granular and interconnected: walking, running, and crawling; looking and hearing; aiming and shooting. Games like The Chinese Room’s Dear Esther (see Figure 1.4) show that these actions can be reconfigured to allow all sorts of other kinds of play experiences. In Dear Esther, the player interacts with the game through the standard first-person perspective. They look and move through a designed space not unlike a full-scale movie set. Though the player aims their view, they are never doing so to shoot. By removing this one action, the designers of Dear Esther create a play experience focused on the exploration of a storyworld that feels radically different, even though it lacks only one standard action.

Figure 1.4 A screenshot from The Chinese Room’s Dear Esther.

Game designers determine the specifics of these core elements of a game, but they have little control over what the player does with them while playing the game. That is why the iterative game design process—involving conceptualizing, prototyping, testing, and evaluating—is so important. We will get into this more in Parts II and III of this book, but by approaching game design as the design of play and focusing on what happens when a game is put into motion, game designers can methodically shape and refine the play experience of their games.

This is easier said than done. Game design produces second-order play experiences for players. By this, we mean that game developers create the game, but the player is the one who decides how, when, and why to play it. Second-order design is a concept loosely borrowed from mathematics and propositional logic. An equation is a proposition, and the insertion of variables is first-order logic. Second-order logic is what emerges when the variables begin to interact. In the context of game design, those variables are the players and how they engage with a game. When do they play? Why do they play? What do they do while playing? What do they feel while playing? Unexpected outcomes emerge when a player plays within the dynamic system of a game.

Katie Salen and Eric Zimmerman refer to this as the space of possibility of a game4—the potential experiences a game designer creates through their combination of objects, playspace, players, rules, actions, and goals. A game’s space of possibility can be focused and specific about what the player will do and experience, and it can be broad and open-ended. anna anthropy’s Queers in Love at the End of the World is a text-based game in which the player spends the last ten seconds before the world ends with her partner. anna has defined the scenario as well as the options of what the player can do within these precious seconds. There is limited time and a limited number of actions to choose from. Queers in Love... has a defined space of possibility because anna had a very specific kind of experience she wanted to share with players. She was more interested in creating a focused play experience that led to reflection than in creating a play experience that offered an open-ended space of possibility for player actions.

4 Katie Salen and Eric Zimmerman, Rules of Play.

On the other hand, there is Minecraft, the open-ended sandbox in which players collect materials so they can create things like buildings, vehicles, and tools. This has led to an endless set of unexpected outcomes—scale models of the Starship Enterprise, functioning rollercoasters, and replicas of entire cities. The space of possibility in Minecraft is quite broad, allowing players to develop their own goals. Even in this seemingly endless possibility, there are limits, however. Players tend to create buildings and vehicles but not sports or forms of life, for example.

In the case of anna anthropy’s text-based game Queers in Love at the End of the World, the possibility space is narrow because anna has a particular expression to convey to players. In Mojang’s Minecraft, the space of possibility is so broad as to seem endless. This, ultimately, is what approaching game design as play design is about—understanding that games create spaces of possibility defined by player experience as much as by game design. The more focused the designer wants the experience to be, the smaller the space. The more the designer wants the players to develop their own experience, the more open the space of possibility will be.

A game’s space of possibility is something we as players never really see in complete form. Instead, it is a quasi-theoretical understanding of the many play experiences players can have inside a game. The thing is, our understanding of a game’s space of possibility is always changing. Take basketball as an example. Until 1980, no one ever realized that it was possible for a player to jump under the backboard in the space between the rim and the baseline.5 But when Dr. J leapt from one side of the basket to the other in that underneath space, suddenly a whole new set of possibilities was added to the game.

What lets a player understand a game’s space of possibility is game state. Game state refers to a particular moment in the game—where the players and objects are in the playspace, the current score, the progress toward completing the game’s goal, and so on. Every time a game is played, it is going to have a different sequence of states, as players will move through their play experiences in different ways. This brings us back around to the second-order nature of games. A game’s design is the creation of a space of possibility that changes from moment to moment based on player input. In real-time games in particular, the game state is in constant flux as play is ongoing. In turn-based games, the state changes less frequently but is still in motion and changing based on player engagement. This is what makes games such a powerful medium—we as game designers create spaces of possibility from the basic elements of games. And players, in turn, bring our games to life through their play.

Getting from Here to There

Designing a game that creates a particular kind of play experience is much easier said than done. This requires us to approach games as designers rather than as players. Making the change from player to designer is not so different from transitioning from being a sausage-eater to a sausage-maker—seeing the messy behind-the-scenes work involved in the process can be unsettling. The next three chapters of Part I, “Concepts,” look more closely at games from a designer’s point of view. Together, these chapters create a play-focused approach to game design. For those new to game design, the chapters in Part I form an understanding of what game designers see and think about when playing and making games. And for those already thinking about games as a designer, these chapters provide our outlook on games as a broad medium suitable for entertainment and expression alike.

Chapter 2, “Basic Game Design Tools,” focuses on the basic tools and principles for shaping play experiences. We look at tools like constraint, abstraction, decision-making, and theme to help us see how game designers create a range of play experiences.

Chapter 3, “The Kinds of Play,” explores the types of play experiences we can create for our players. This encourages designers to think about games as play experiences rather than as media products. Competitive, cooperative, chance-based, whimsical, performative, expressive, and simulation-based play are all looked at in detail. We look at a variety of games in the process to help us understand the incredible range of play experiences we can provide our players.

Chapter 4, “The Player Experience,” examines the ways players perceive games, how they make sense of the information encountered while playing, how they decide what actions to take, and how they understand their role in the game. In other words, this is what we ask of players during play experiences.

Summary

When game designers think of games as frameworks for play experiences, they recognize that games are generative. There are many kinds of games, but they all share the same basic elements: actions, rules, goals, objects, playspace, and players. These parts interact to generate play. As a designer, the challenge of creating play experiences is that they represent a second-order design problem: we are designing the play experience indirectly through the game. But there are ways to accomplish this, and the upcoming chapters will show you how.

The basic elements of games:

![]() Actions: The activities players carry out in pursuit of the game’s goals

Actions: The activities players carry out in pursuit of the game’s goals

![]() Goals: The outcome players try to achieve through their play, whether they be measurable or purely experiential

Goals: The outcome players try to achieve through their play, whether they be measurable or purely experiential

![]() Rules: The instructions for how the game works

Rules: The instructions for how the game works

![]() Objects: The things players use to achieve the game’s goals

Objects: The things players use to achieve the game’s goals

![]() Playspace: The space, defined by the rules, on which the game is played

Playspace: The space, defined by the rules, on which the game is played

![]() Players: The operators of the game

Players: The operators of the game

Additional important concepts:

![]() Second-order design: Designing games is a second-order design activity because we create the play experience indirectly through a combination of rules, actions, and goals. The game only takes form when activated by the player.

Second-order design: Designing games is a second-order design activity because we create the play experience indirectly through a combination of rules, actions, and goals. The game only takes form when activated by the player.

![]() Space of possibility: Because games are interactive, they provide for players a variety of possible actions and interpretations. While a designer can’t predetermine all the possible actions and experiences players will have, they can limit or open up the space of possibility through the game’s combination of actions, rules, goals, playspace, and objects.

Space of possibility: Because games are interactive, they provide for players a variety of possible actions and interpretations. While a designer can’t predetermine all the possible actions and experiences players will have, they can limit or open up the space of possibility through the game’s combination of actions, rules, goals, playspace, and objects.

![]() Game state: The “snapshot” of the current status of game elements, player progress through a game, and toward the game’s (or player’s) goals. Game state is constantly in flux based on player engagement with the game.

Game state: The “snapshot” of the current status of game elements, player progress through a game, and toward the game’s (or player’s) goals. Game state is constantly in flux based on player engagement with the game.

Exercises

1. Identify the basic elements in a game of your choice (actions, goals, rules, objects, playspace, players).

2. As a thought experiment, swap one element between two games: a single rule, one action, the goal, or the playspace. For example, what if you applied the playspace of chess to basketball? Imagine how the play experience would change based on this swap.

3. Pick a simple game you played as a child. Try to map out its space of possibility, taking into account the goals, actions, objects, rules, and playspace as the parameters inside of which you played the game. The map might be a visual flowchart or a drawing trying to show the space of possibility on a single screen or a moment in the game.

4. Pick a real-time game and a turn-based game. Observe people playing each. Make a log of all the game states for each game. After you have created the game state logs, review them to see how they show the game’s space of possibility and how the basic elements interact.

All materials on the site are licensed Creative Commons Attribution-Sharealike 3.0 Unported CC BY-SA 3.0 & GNU Free Documentation License (GFDL)

If you are the copyright holder of any material contained on our site and intend to remove it, please contact our site administrator for approval.

© 2016-2026 All site design rights belong to S.Y.A.