Games, Design and Play: A detailed approach to iterative game design (2016)

Part I: Concepts

Chapter 3. The Kinds of Play

This chapter is a catalog of many of the different kinds of play experiences game designers create using the basic game design tools. These kinds of play include: competitive and cooperative play, play based on skill, experience or chance, whimsical play, role-playing, performative and expressive play, and simulation-based play.

Videogames are usually thought of in terms of genre—first person shooter, puzzle platformer, survival, horror, and so on. This provides one way to make it easy for players to understand what a game is and for developers to operate within the conventions of expected play experiences. But this also has a couple of side effects—it treats games like categorized commodities rather than lived experiences, and it limits the potential of what game designers can try to create for players. Instead of thinking about genre, we prefer to think about the kinds of play our games provide players. This allows us to imagine what the experience will be without set boundaries, beyond marketing niches.

Thinking broadly about the kinds of play lets us focus on the sort of play experience we want to give our players. Lots of fast decisions they don’t have to think much about? A smaller number of decisions that require strategy and analysis? Or very simple interactions that emphasize the visual, aural, and emotional experience? Lots of story? No story at all? Cut-throat competition? Or cooperation instead? A game that emphasizes designer expression? Or one that puts player performance at the forefront? These are just a handful of the things that make up play experiences.

This chapter breaks down some of the primary kinds of player tastes, looking beyond genres like first person shooters or puzzle games or platformers to focus on the more essential play types. We categorize the kinds of play as competitive and cooperative play; play based on skill, experience, or chance; whimsical play; role-playing; performative and expressive play; and simulation-based play.

One important note before we begin. Like tastes in food, the kinds of play are not mutually exclusive. Where a dish might call for garlic, onions, oregano, and thyme, so a game’s design may require a mix of competition, player expression, and whimsy. Keep this in mind as you review this chapter. We delineate the kinds of play to bring clarity and focus to how they work, but ultimately, how they are blended is up to you.

Competitive Play

In a competitive game, some players will win and some will lose. This creates a context of competition in which players or teams of players try to come out ahead of their opponent, whomever or whatever that might be. For example, in soccer, the winner is the team that gets the most points by the end of the game’s time limit. This is certainly the case with sports and most multiplayer games.

Messhoff’s Nidhogg (see Figure 3.1) is a local multiplayer game—a videogame played by two or more players gathered in the same space in front of a shared screen. In Nidhogg, all the actions players perform are in service of pitting one player’s skills against the other’s—running, jumping and ducking, and thrusting or throwing a sword. The goal: to make it to the far end of the world before her opponent does. To gain an advantage, the player must attack her opponent to get past him, if only by a split-second advantage. There’s a laser-like focus to Nidhogg. Everything about the game’s design encourages you to compete against your opponent. There isn’t much else you can do within the game’s space of possibility.

Figure 3.1 A screenshot from Nidhogg.

One of the things we find often in competitive games is yomi. Yomi is the Japanese concept for knowing the mind of your opponent. It’s usually applied to one-on-one competition, but it can also be found in sports, where one team analyzes the other team’s past play to predict future actions, all in service of gaining strategic advantage. In a game like Nidhogg, this means trying to predict what the opponent is going to do so that the player can make a move that takes advantage of the weaknesses in her opponent’s strategic tendencies. Yomi often comes in layers. In a game of Nidhogg, the player may think that her opponent is going to parry with his sword. But he guesses that’s what she thinks he’ll do, so he thinks he’ll jump instead. But she knows he knows she thinks he’ll parry, so she gets ready for him to do something else. This example illustrates how recursive yomi can be, where strategies and counter-strategies are all devised by trying to get inside an opponent’s head.

This is where competition in some games gets really fascinating—designed spaces where players can think about not only their own decisions, but those of their opponents, too. Yomi is when the interplay of a player’s skill and strategies come up against the uncertainty of another player’s skill and strategy. What drives this is the pursuit of the game’s goals by both players. So yomi is most seen in games with explicit goals in which one player or team wins and the other loses.

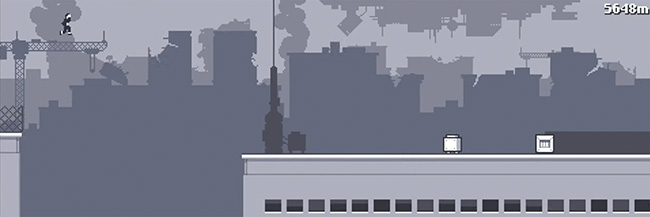

Competition isn’t always head to head. In videogames, players often compete with one another in single-player games. Take Semi Secret Software’s Canabalt (see Figure 3.2), a single player “endless runner” in which the player controls a little runner heading across a side-scrolling environment. The player has one action they can take: jump. This allows them to propel the player character over obstacles on the rooftops, avoid objects that fall from the sky, and jump from building to building. The longer the player lasts, the faster the game gets, until the player character hits its maximum speed. The only way to slow down is to run into obstacles on the rooftops.

Figure 3.2 A screenshot from Canabalt.

In Canabalt, the score measures the distance the player ran before getting crushed by a falling object or falling off a roof. At the end of a game, the score is posted to the scoreboard, and the player has the opportunity to share their score via Twitter. This creates a form of competition in which one player sees another’s score and compares it to their own. Sometimes Canabalt tournaments are run, in which the game is projected on a big screen, and players take turns playing, with the winner being the player with the longest run. This creates a different kind of asynchronous competition in which players are playing in one another’s presence with a group of spectators.

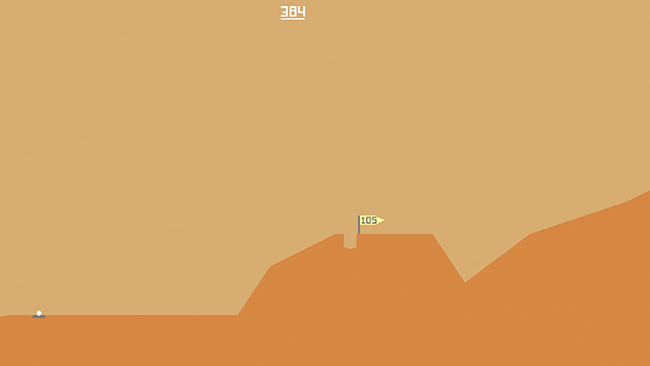

Another basic form of competition comes in players competing against the game itself—the challenge of reaching a game’s goals, in other words. A great example is Captain Game’s Desert Golfing (see Figure 3.3). The name is quite descriptive. Using an Angry Birds-style gesture, the player aims and “hits” a golf ball toward a hole in the desert. Players are competing against the game in two key ways—navigating the ball around the terrain, and mastering the aim-and-shoot action. This kind of player-versus-game competition is another way to think about challenge. A game like Desert Golfing provides the player with pleasure through the pursuit of mastery by providing resistance and challenge. Players pit themselves against the game, doing their best to overcome the obstacles the game places in their path.

Figure 3.3 A screenshot from Desert Golfing.

In looking at Nidhogg, Canabalt, and Desert Golfing, we see three approaches to designing competition—head-to-head competition, which adds layers of complexity to the decisions players make; asynchronous competition, in which players compete, but in ways measured by their performance rather than by the outcome of head-to-head play; and competition against the machine, which emphasizes the challenge of mastering actions to pursue the game’s goal.

Within competitive games that pit players against one another directly, there are two additional ideas to consider—symmetrical and asymmetrical competition. Die Gute Fabrik’s Johann Sebastian Joust (see Figure 3.4) is an example of symmetrical competition. Players have the same abilities—to move around the playspace, to hold their PlayStation Move Motion controllers aloft, and to use their bodies to jostle their opponent’s controller to knock one another out of play. We call this symmetrical competition because the players have shared actions with which they compete with one another in pursuit of a common goal. In the case of JS Joust, this is to be the last player with his controller still active. This kind of play is found in most competitive games, as it is the most common approach to designing competitive play.

Figure 3.4 Johann Sebastian Joust. Photo by Brent Knepper.

Asymmetrical competition is found in games in which players have different actions, objects, or goals. A great example is Chris Hecker’s Spy Party (see Figure 3.5). The game pits one player, the sniper, against another player, the spy. The spy plays one of a dozen or so characters attending a party, with all the other characters operating as nonplayer characters (characters controlled by the computer). The spy moves around the room, “talks” with other guests, and performs a series of missions in the hopes of remaining undetected. The sniper’s goal is to figure out which character the spy controls as he maneuvers around a crowded party. The sniper can look at the room and zoom in to get a closer look, and if she thinks she has figured out who the spy is, she has one bullet with which to shoot him. If the spy remains undetected at the end of the allotted time, he wins. If the sniper shoots the spy before time ends, she wins. If the sniper shoots the wrong person, then the spy wins. The game sets up a wonderful “cat and mouse” asymmetry that, while still in prerelease, has already spawned a fan WIKI and innumerable “Let’s Play” videos.

Figure 3.5 Screenshots of the sniper view (top) and the spy view (bottom).

Cooperative Play

Though it is by far the most prevalent form of play, competition isn’t the only way to interact with other players. Sometimes, people feel like cooperating. These are play experiences in which players work together to achieve the game’s goals. One of the things about cooperative play is that when it goes well, it is one of the best kinds of fun you can have. You and your collaborators are in sync, making things happen that none of you could do on your own. Like a well-executed pass in a soccer match leading to a goal, you are in sync with someone else, working to meet a shared goal.

One of our favorite cooperative games is Valve’s Portal 2 (see Figure 3.6). There is a single-player campaign, but in our opinion, the more enjoyable play experience is the two-player cooperative campaign. The players inhabit ATLAS and P-body, two robots inside Aperture Laboratories’ test center. Working together, they solve the spatial puzzles of the game. In some cases, the two have to time their actions, while in other situations one player has to create portals for the other. Throughout, the level design and puzzle design create a collaborative, cooperative play experience.

Figure 3.6 Our friends Brian and Robert conferring during a game of Portal 2.

Portal 2 is also a great example of symmetrical cooperative play. This refers to games in which the cooperating players get to use the same actions and have the same basic attributes. With Portal 2, both player characters look different, but they shoot portals, run, and jump in the same way. Neither has a built-in “role” in the collaboration. This leaves space for the players to develop and put into action strategies that may end up with one player doing one thing and another doing something else. The important point here is that this is left to the players to decide, not the designers.

An example of asymmetrical cooperative play is Matt Leacock’s board game Pandemic. In Pandemic, players work together to protect the world from a set of four deadly diseases. If the players don’t work together, the game will easily defeat them. Together, the players work to cure each disease by moving around the gameboard, healing cities and treating virus outbreaks. Players are assigned roles like Dispatcher, Medic, and Scientist that each have their own special abilities. These different roles assumed by the players create the asymmetry. The Medic can clear up diseases more quickly, while the Dispatcher can facilitate the movement of other players around the board. This creates asymmetrical cooperation in which the players work to figure out how to best utilize the differences in the characters to achieve the game’s goal.

Coco & Co.’s videogame Way (see Figure 3.7) is another great example of cooperative play, drawing on the symmetrical cooperation model in an interesting way. Way is a two-player puzzle platformer where players take turns solving puzzles over the Internet. The active player doesn’t know exactly how to solve the puzzle because they can’t see everything in the playspace, while the inactive player can see the full puzzle space. Way quickly becomes about learning to communicate through nonverbal cues to solve the puzzles so that the players can share information with one another. The active player will move in a particular direction, or perform a particular task, and the inactive player will try to convey whether or not the active player is getting closer to or further from the solution using body language. Way is an example of a third kind of cooperative play: symbiotic cooperation. By this, we mean the players are reliant on one another to play the game. Without the assistance of the other player, it is close to impossible to make your way through the game with all of its invisible platforms.

Figure 3.7 A screenshot from Way.

What we see with cooperative play is the design challenge of creating a truly collaborative experience for players, one in which it is impossible to meet the game’s goals alone, requiring players to work with each other to find success. Whether it be symmetrical, asymmetrical or symbiotic, cooperative play is an important kind of play.

Skill-Based Play

With both competitive and cooperative play, players are asked to develop skill to perform the game’s actions in pursuit of its goals. Soccer asks us to have skills in order to run, start, stop, and change directions, but also to become deft in manipulating the ball with our feet, our knees, the tops of our head, and even our chests. This is one core kind of play: skill-based play. We can further break skill down into active skill and mental skill.

Team Meat’s Super Meat Boy is a great example of a game that requires active skills. The game falls decidedly in the “masocore” category of games that require a good deal of skill around precise movement and timing. The player controls Meat Boy, who has the goal of getting from point A to point B, where Bandage Girl awaits. To do this, the player must move Meat Boy around through side-to-side movement and jumping. Like many platformers, Super Meat Boy requires nuanced twitch response and timing. Unlike the other SMB, Super Mario Bros., Super Meat Boy requires players to make use of speed and pin-point accurate timing to climb walls. To play the game, you need to develop skills to gauge distances and time jumps and wall climbs. And, like many incredibly challenging games, developing those skills involves failing over and over again and learning from hundreds, sometimes thousands, of failures.

For mental skill, a great example is Thekla Inc.’s The Witness (see Figure 3.8). The player explores an empty island filled with a series of path-tracing puzzles that unlock buildings, turn on machines, and generally bring the island to life. While the player does have to move around the world and trace the puzzles, the challenges they confront are mostly mental. For example, in some of the puzzles, they must remember the path of an adjacent puzzle and then trace its mirror image on an otherwise invisible puzzle space. The execution of this is easy enough, but the mental challenge of remembering and inverting the sequence is where the skill lies.

Figure 3.8 A screenshot from The Witness.

Still other games combine these qualities to create play experiences that draw upon both active and mental skill. Portal comes to mind here. The game’s designer, Kim Swift, wanted to put pressure on the player’s ability to enact the solution to the puzzle. To do this, Kim added time pressure. The player has to make precisely timed portals that allow them to shoot the portal, jump through, duck, and then shoot another portal, all while avoiding the high-energy pellets. To know when, the player must think through the spatial puzzle, execute well-timed portal shots, and then move through them to avoid being hit by the pellet. So the game requires both excellent hand-eye coordination and timing, but also the additional mental skill of sorting out a solution to the puzzle.

What connects these three examples—Super Meat Boy, The Witness, and Portal—is the design of challenges that put pressure on different kinds and combinations of skill. The more accurate or developed the skill requirements, the more time it will require of players to get to the point they have acquired the requisite skill mastery. This might limit the number of players who will be willing to commit to playing and mastering these skills, but it also makes the rewards of achieving victories great.

Experience-Based Play

What if you want to provide players with an experience that isn’t built out of overcoming skill-based challenge but instead focuses on other aspects of the play experience? A good example of this is The Chinese Room’s Dear Esther (see Figure 3.9). The player explores an island on which they find a series of letters a man wrote to his deceased wife. By moving through the island, exploring the contents of buildings and reading the letters, the player unfolds the story of the man and his wife. So long as the player understands the basic mechanisms for navigating a 3D first-person game (not something we can easily take for granted, as we will discuss in Chapter 4, “The Player Experience”), they will be able to experience the story the developers created. The core of the experience is exploration, enjoying the design of the spaces, and of course, unfolding the story between the man and wife.

Figure 3.9 A screenshot from Dear Esther.

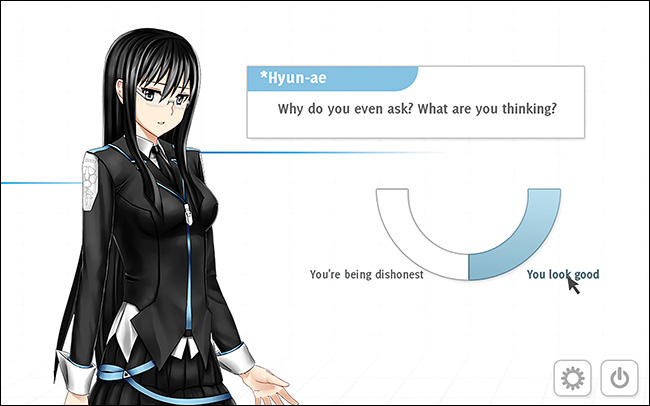

In text-based games like Christine Love’s Analogue: A Hate Story (see Figure 3.10), players experience a story through a combination of text, image, and interaction prompts. The player takes the role of someone in the future who has stumbled upon a broken computer system. Sometimes players are asked to type inputs into a command-line prompt, while in other situations they simply make choices from a list of options. Yes, there are decisions to be made, but because the game isn’t competitive or skill based, the player is left to focus on the text and the images and to consider the meaning of the story.

Figure 3.10 A screenshot from Analogue: A Hate Story.

Even within games that are competitive on the surface, players can find other forms of experience. The folkgame ninja is a great example. Players stand in a circle and take turns making one move that ends in a “ninja” pose. The basic goal is to hit the hands of one of the adjacent players, while avoiding having your own hands hit. Though this sets up a competitive premise and does involve physical and strategic skill, most games of ninja are played with emphasis on acting like a ninja, being part of the experience as a group, but not really on winning or losing. As ninja suggests, many games can be played for experience instead of competition or skill development, as long as the game’s designer has left room within the space of possibility.

In these three examples, we can see three approaches to experiential play—that of navigating a 3D space to experience a story (Dear Esther), that of a combination of text and image to piece a story together (Analogue: A Hate Story), and that of physical activity that emphasizes communal engagement over winning (ninja).

Games of Chance and Uncertainty

The games we’ve looked at so far in this chapter have focused on play styles in which the structure and outcome of the experience are in the hands of the player or the game’s designer. But what happens when you bring chance into the mix? This is, of course, the basis of many cardgames like poker or blackjack. But we can find this sort of mix in other games, too.

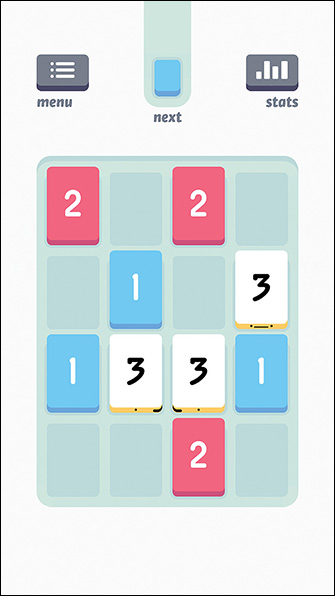

A game that mixes chance and skill in interesting ways is Sirvo LLC’s Threes (see Figure 3.11), a mobile puzzle game in which players drag tiles around to combine them into multiples of threes. A 1 tile and a 2 tile create a 3 tile, which combined with another 3 makes a 6, two of which create a 12, 24, 48, and so on. Every move the player makes concludes with a randomly selected tile loading onto the grid, so the player never knows exactly what is coming down the pipe. When the grid is filled with tiles and there are no more possible moves, the game is over.

Figure 3.11 A screenshot from Threes.

Players have to develop strategies to combine as many tiles as possible with each move. So Threes is a game involving the strategic management of uncertainty—the player doesn’t know exactly what kind of tile they will get, so part of their strategy is about managing their moves to anticipate a variety of outcomes. The game does provide players with some information, however. There is an indicator letting the player know what color tile will drop next. This comes in handy in thinking through the placement of tiles, particularly when the board is nearly filled. In this light, Threes is a game that encourages players to develop skills to navigate uncertain events in the game, plan their next actions, and develop longer-term strategies around obtaining the game’s goal.

Android: Netrunner (see Figure 3.12), Lukas Litzsinger’s reboot of Richard Garfield’s Netrunner, is an asymmetrical card game in which one player, the Runner, attacks the other player, the Corporation, to steal Agenda points from the Corporation. The Corporation, in turn, tries to defend itself while secretly scoring Agenda points before the Runner can steal them.

Figure 3.12 A game of Android: Netrunner.

The game mixes strategy, skill, chance, and uncertainty in interesting ways. Before the game starts, the two players construct their deck of cards for play. The players then separately shuffle their decks so that the cards will appear in a random order during the course of play. If the players have constructed their decks well, they will have strategies for playing Agendas (if they are the Corporation), or in the case of Runners, stealing Agendas. Players have to weigh the probabilities of a particular card appearing in the flow of the game. As a result, if there is a card that the player really wants to use, they have to put in three of that card (the maximum allowed). In a deck of 45 cards, that means 1/15 of the player’s deck is that particular card, giving them a fair chance in the flow of a game that they will draw that particular card in time to put it to use.

But just getting one particular type of card to come up isn’t enough to succeed. Players have to think through strategies involving the possible interplay of several different kinds of cards and think through the probabilities of them emerging in ways that allow them to be played together. So players have to develop strategies that take advantage of the actions chosen for that deck, such as developing “engines”—or chains of cards—that help pursue or protect Agendas, remembering what cards are in their deck, which have already been played, and which are likely to come up soon. They must then balance these strategies against the chance of the shuffled deck by managing their own uncertainty of the strategies of their opponent. Android: Netrunner requires that players intuit the strategies their opponent will put into play, trying to make sense of the available information and guess what lurks in their deck, or in the case of the Corporations, their unrezzed cards (the still face-down cards the Corporation has put into play).

The proportion in which you use strategy, skill, chance, and uncertainty is one of your considerations as a designer. It’s like cooking and the choice you have between sweet, salty, sour, and spicy, or how and in what proportions you combine all four. Like many aspects of game design, chance is like a tasty spice. The right amount makes food taste great, too much can be overbearing, and not enough can make things bland. And our tastes change as we move through life. To young children, Candy Land (see Figure 3.13) seems like the best game ever. (Play it with a four-year-old some time; you’ll see.) But at some point, the complete lack of choice and the total reliance on chance gets old. There is no player decision-making in the game. Players just spin the spinner (or draw cards, if you are playing an older version) and then move accordingly. For children, the illustrations and the imaginative play of the Candy Land world is more than enough to make the game fun, but for many others, that just isn’t enough.

Figure 3.13 A game of Candy Land.

Purely chance-based games remove decision-making from the player experience. Threes suggests smart ways to use strategy and chance to enhance the variety of decision-making for players. Android: Netrunner employs strategy, chance, and skill built over multiple games (and losses) to create a unique play experience. Android: Netrunner is a great example of a game that requires mental skill within a chance-based context. And Candy Land reminds us that chance has to be carefully managed to keep players engaged.

Whimsical Play

And now for something completely different. While most games designed around the interplay of strategy, chance, and uncertainty tend to be pretty serious, there are other play styles that are funny and whimsical. This sort of play feels like a ride at an amusement park (see Figure 3.14) or kids rolling down a hill. Whimsical play emphasizes silly actions, unexpected results, and creating a sense of euphoria by generating dizziness and a play experience that you need to feel to understand. Three videogames that embody this sort of experience are Kaho Abe’s Hit Me, Bennett Foddy’s QWOP, and Keita Takahashi’s Tenya Wanya Teens.

Figure 3.14 A ride at Coney Island.

Hit Me (see Figure 3.15) is a videogame (actually, more of a combination digital/physical game) in which two players don safety hats outfitted with big red buttons and then proceed to try to push one another’s button. Literally. The two players simultaneously strain to reach the other’s button on their helmet and keep their own helmet out of reach. Thanks to the circle within which the game takes place, the two players are forced to stay close together, which increases the chaotically silly energy of the game. That the game is played with a group of spectators is important, as this further adds to the silliness—people laugh, gasp, and cheer as the players try to hit one another’s buttons. Hit Me becomes a caricature of cartoon-like combat. Should a player hit their opponent’s button, style points are earned by having the best picture taken. (The buttons also house cameras pointed at the opponent.) The judge and spectators reward style points for the best pictures. This changes the dynamics of the game. It becomes as much about the picture-taking as about the physical interactions. Everything from the design of the hats to the actions and goal of taking creative photographs of the other player as you hit their button creates a whimsical experience framed by the silly behaviors players enact in pursuit of their goals.

Figure 3.15 A game of Hit Me.

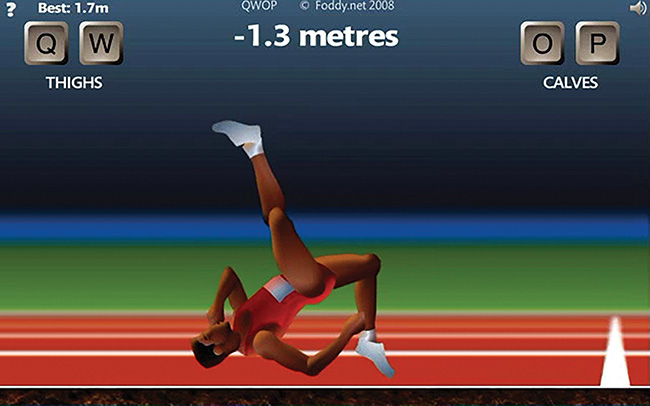

Another game with lots of whimsy is Bennett Foddy’s QWOP (see Figure 3.16). The game seems straightforward: players try to propel a runner along a track using the Q, W, O, and P keys on a QWERTY keyboard. Things get challenging, and funny, based on the way the keys are mapped to the runner’s skeletal system. Instead of making the act of walking trivial like most videogames do, the Q and W map to the runner’s thighs, while the O and the P to the runner’s calves. This sets up a very challenging goal—keep the player upright and moving forward. The upper body is completely at the whim of the positioning of the legs, often flopping forward and backward, causing the runner to collapse after just a few steps. In designing QWOP, Foddy played with constraint—in this case on how players manipulate a humanoid to run—to develop a whimsically frustrating play experience.

Figure 3.16 A screenshot from QWOP.

QWOP brings out whimsy in different ways than Hit Me. Instead of having players use their bodies to create the playfulness, QWOP relies on awkward, intentionally difficult skeletal rigging and button control of the onscreen character. Most games make controlling player movement trivial—simply press the proper key, or push the correct stick, and the onscreen character moves. But QWOP plays with these ideas to create a truly whimsical play experience.

An example of conceptual whimsy is Tenya Wanya Teens by Keita Takashi and Uvula with the assistance of Wild Rumpus and Venus Patrol (see Figure 3.17). The game’s silliness starts with its controller: a joystick next to a panel of 16 buttons with no identifying labels. The player is tasked with helping a little onscreen boy perform the appropriate task by pressing the correct button on the controller. So sometimes, this means the player makes the character cry when it should be bathing, or rock out on a guitar when the character should be sleeping. The game doesn’t ask the player to physically move or act silly, but it does lead to all sorts of onscreen hilarity. Adding to this is the speed with which the game changes environments and tasks—nearly every 10 seconds, the character is presented with a new activity, and the player has to find the right button to perform the task.

Figure 3.17 A game of Tenya Wanya Teens.

Whimsical play is often about physical silliness. Spinning around on a merry-go-round and then trying to walk is whimsical play. Twister and the ways it asks the player to move their body around other players is whimsical play. As we see in Hit Me, a careful interplay of actions and goals can set up silly interactions. With QWOP, whimsical play can be produced through the careful application of constraint to player actions. Whimsical games like Hit Me and QWOP emphasize the role of the body, and differently from sports, focus on our physical foibles over our skillful grace. And with Tenya Wanya Teens, the silliness is conceptual, as the comedic design of the unexpected outcomes from the player’s attempts to click the correct button lead their character to perform actions that don’t match their setting. And in so doing, the designer has created whimsy through the interplay of actions, goals, and theme.

Role-Playing

For many people, games are a form of storytelling. Perhaps better stated, they are a form of story experience; as the player engages with the game, and through their actions, the story unfolds. There are multiple traditions of storytelling that wind through games, from the character-driven experience of tabletop role-playing games to the more cinematic storytelling associated with many AAA titles. Let’s look at an example of both kinds: Leah Gilliam’s tabletop RPG Lesberation: Trouble in Paradise, and Tale of Tales’ first-person dark fairytale The Path.

Leah Gilliam’s role-playing game Lesberation: Trouble in Paradise (see Figure 3.18) puts players in the role of a group of lesbian activists trying to establish a utopian society. The game’s structure is much simpler than the average RPG. Players are given a set of cards representing objects—coffee mugs, Volkswagen minivans, microphones, rope, and so on—and verbs—rock, love, shout, know, and so on. Players lay their cards out face-up so that everyone can see what everyone else has. Players then take turns playing a card of each type to advance the story scene established by the game-runner. Players have to agree upon decisions as a group and can use other players’ cards with permission. The game promotes discussion and consensus-making within a socio-political scenario.

Figure 3.18 A game of Lesberation: Trouble in Paradise. Photo by Leah Gilliam.

Lesberation: Trouble in Paradise uses the basic ideas and structures of role-playing games, but in a way that is accessible to a larger audience. No character sheets, no long rules manual, and no monster manual are needed to play the game. There are just a few simple rules for role-playing a group of activists in a near future scenario. We could pretend to be in those roles without a game, but the light structure of Lesberation makes the experience more enjoyable and facilitates the creation and interaction of the characters.

That is really what this sort of play is about: providing the structure within which stories unfold through role-playing. Jesper Juul has referred to this as games of emergence.1 By this, Juul refers to a space of possibility that is in part defined by how its players enact the actions, objects, and playspace. Lesberation allows players to develop stories within a loose set of rules through which all sorts of possibilities can emerge, limited only by players’ imaginations.

1 Jesper Juul, “The Open and the Closed: Games of Emergence and Games of Progression.” www.jesperjuul.net/text/openandtheclosed.html. 2002.

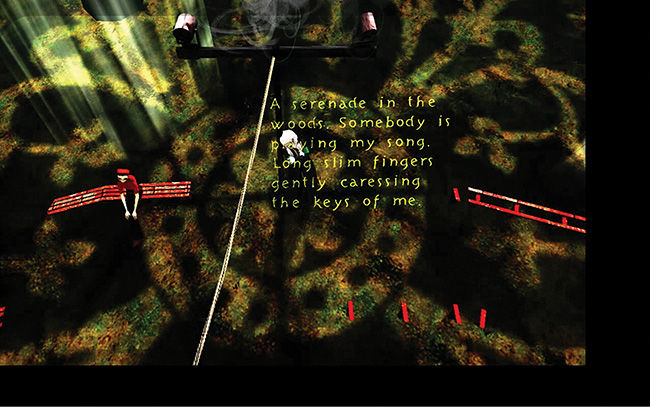

Tale of Tales’ The Path (see Figure 3.19) is a very different kind of role-playing game. Rather than the character and the events being generated by the players, it is designed by the game’s creators and experienced by the player. The storyworld of The Path is loosely based on the Little Red Riding Hood fairytale. Six sisters between the ages of 9 and 19 are on the outskirts of a forest. The girls’ mother asks that one of them run over to their grandmother’s house in the woods. The player picks one of the six sisters to inhabit on the journey. As the game progresses, players inhabit all six characters and experience the world through their eyes. This sort of role-playing experience happens inside a predefined storyworld, one authored by the gamemakers and unfolded by the player.

Figure 3.19 A screenshot from The Path.

This approach is much closer to movies in that a tighter storyworld can be constructed, with characters and situations designed by the gamemakers rather than by the players themselves. While this approach provides less open-ended play, it provides richer, authored storyworlds to investigate. Jesper Juul refers to this as games of progression—those in which the player makes decisions, but all possible outcomes are already defined by the game’s creators. In The Path, players are free to choose to wander into the woods, but nothing they see or encounter exists without having been preauthored by the game’s creators.

A similar example is Porpentine’s text adventure Howling Dogs. Instead of using 3D representations of a space, the game is delivered entirely through text. Players navigate through Porpentine’s surreal storyworld by clicking on text links inside the game. The story is set in a dystopian prison in which the player engages with virtual reality devices. The experience is heightened through its text-based narrative in the same way novels provide us with opportunities to imagine the worlds they present to us. Because of the fractured structure of the game’s story, players are left to move through the space in a more impressionistic manner, seeking to construct an understanding of who their character is and why they are where they are. Howling Dogs drops us into a role that we must play through to begin to understand. Attempting to find a traditional story progression will only lead to frustration, but embodying the experimental nature of both the format—interactive fiction—and the storyspace provides for a deeply striking experience.

What we see in Lesberation, The Path, and Howling Dogs are three of the many ways role-playing can be experienced inside a game. Lesberation lets players generate their own stories by providing a structure and set of processes for collaboratively telling a story. It’s a system that establishes the general rules for storytelling and lets players feed their story through these rules to create an emergent play experience. The Path, on the other hand, has a preauthored story that the player explores by moving through the gameworld. In The Path, players experience the game differently through each of the sisters, playing a series of roles that are defined by the game. It’s like a machine that contains the threads of the story, delivering each thread as players experience each of the characters that delivers a progressive play experience. Howling Dogs is similar in structure, but instead it uses branching text structures to deliver the story experience and help the player piece together who they are. The player makes choices, and as they do so, they experience one path through the story. These three examples mark the different approaches to how role-playing can tell stories in games, as games of emergence and games of progression. And there are many ways in between.

Performative Play

Some games use performance as the core of the play experience. When they do, they’re often as much fun to watch as they are to play; generating dramatic action and acting. A game of Charades is based on player performance, adding challenge by taking away some of the expressive abilities like speech to emphasize the qualities of gesture to give clues to the team. Hasbro’s Twister provides yet another form of physical play: using a spinner to randomly select the color players must place their feet and hands on, within the colored dots on a floor mat. This creates a form of modern dance where the fun is all in the foibles of the body. Two videogames illustrate different kinds of performative play: Die Gute Fabrik’s Johann Sebastian Joust and Dietrich Squinkifer’s Coffee: A Misunderstanding.

The hybrid physical/digital game Johann Sebastian Joust (see Figure 3.20) generates improvisational performance through the physical interplay of players attempting to jostle each others’ controllers. Players also need to listen to the game’s classical music score to learn the speed with which they should move. When the music is slow, players also move slowly—carefully protecting their controllers. When the music speeds up, play becomes more frantic, with players making faster moves and larger gestures. To the spectator, the dance of the players to the music looks like mercenaries at a classical ballroom dance.

Figure 3.20 A game of Johann Sebastian Joust. Photo by Elliot Trinidad. Used with permission of the IndieCade International Festival of Independent Games.

Like a playground game, JS Joust is flexible, allowing for individual or team play. But it is also a videogame in the tradition of Wii Sports, where the Playstation Move Motion controller provides feedback and input into the game and is responsive to different musical styles and speeds. What JS Joust emphasizes the most is player performance—in terms of agility and strategy, but also in the sense that there is a dance that everyone is participating in. The interesting thing is that the players, who are deeply absorbed in keeping balanced while unbalancing everyone else, have little time to think about what they are doing or what they look like while doing it. So JS Joust is performative, but in a fairly unselfconscious way that spectators observe more than the players are aware of. Absorption becomes an important design tool for creating unselfconscious play, as it takes the player’s mind away from their everyday focus on self-presentation and opens them up to an unselfconsciously performative play experience.

A very different example is Dietrich Squinkifer’s Coffee: A Misunderstanding (see Figure 3.21). In this theatrical game, two players perform as online friends meeting in person for the first time at a fan convention. The players receive prompts for how to interact with one another via their phones from the game’s moderator. How they interpret and enact the prompts is up to the players: will they work together to have an enjoyable experience? Will they be at odds and create a tense conversation? Will the conversation simply be awkward? To add to the challenge of maintaining a conversation, two audience volunteers are given a mobile device that allows them to choose key moments and topics in the conversation. As Dietrich describes it, “It’s a combination of multiplayer Choose Your Own Adventure and improv theatre, resulting in a play experience that’s every bit as awkward as the story it’s trying to tell.”2Dietrich points out an important aspect of this sort of performative play—there is a deliberate, self-conscious performance in this game that very much adds to the game’s effect on players and spectators alike.

2 From the description of the game on Dietrich Squinkifer’s website (http://squinky.me/my-games/coffee-a-misunderstanding/).

Figure 3.21 A game of Coffee: A Misunderstanding.

Games can often act like a score for player performance, generating dance, acting, and acrobatics emergent from the game’s play. With JS Joust, we see a form of performative play that asks players to abandon themselves to the game in a way that enables performance within the game and for those watching the game. The more focused a player becomes, the more performative they are. Coffee: A Misunderstanding takes a very different approach, keeping players keenly aware of their actions and the potential for awkwardness and vulnerability. The game asks players to perform within the context and prompts designed, but the way players deliver their lines and the choices made by the audience volunteers add to the unpredictable playfulness of the experience.

Expressive Play

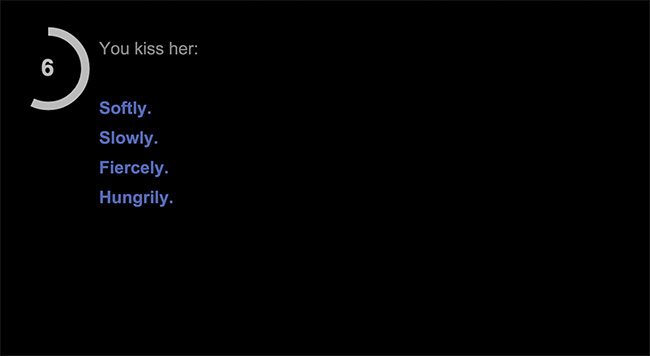

A related form of play is expressive play: play that expresses a feeling or concept, whether intended by the designer or derived from the player. This idea of artistic expression is usually associated with music, film, literature, and painting, but not games. However, increasingly, gamemakers are using games to express ideas and feelings. Two examples of this are anna anthropy’s Queers in Love at the End of the World and Elizabeth Sampat’s Deadbolt.

Queers in Love at the End of the World (see Figure 3.22) is a text-based game in which actions are presented in the form of hyperlinks. The player has only 10 seconds to play the entire game. In the final fleeting moments of the world, the player steals a kiss, tries to say something, looks at the sky...all within 10 seconds. And then the game ends. If the player chooses to restart the game, they can try to see all of the paths not taken—wonder how much can be done in such a short amount of time and experience worry, desire, and regret condensed into the short gameplay. It uses only text and a countdown timer, but trying to read everything and make choices only emphasizes the urgency of the gameplay and of the narrative of a world ending. Queers in Love at the End of the World expresses much in such a short amount of time: how we often wrestle with how to express the way we feel about our partners, our feelings around life ending when there are things left unsaid and not done, and the fleeting quality of a moment. So the game is expressive both for anna and for the player in making their decisions and reflecting upon their meaning.

Figure 3.22 A screenshot from Queers in Love at the End of the World.

Elizabeth Sampat’s Deadbolt is a tabletop role-playing game structured around personal reflection and conversation. Play begins with players filling out the key—a simple set of evaluations of the other players including who among the players is most intimidating, most beautiful, best known, least known, and so on. Once everyone has filled out the key, the players then open two envelopes: Signifier and the Question. Signifier lets the player know which player they will talk to first. The second envelope lets the player know what question will be asked. Conversations then begin around the prompts.

First, players are asked questions about themselves, and then about the other player. In the third round, players are given blank cards onto which they can write a comment or question for one of the other players. These cannot be viewed by the other player until the game is over. At that point, free from the structure of the game, the player can choose to engage with the other player who gave their comment or question. If a player is emotionally affected by the final card but doesn’t want to speak about it, they can give the player who gave them the card a Deadbolt button.

Expressive play is a form of play that often subverts player choice in an effort to clearly express and share something about the human experience. In the case of Queers in Love at the End of the World, our choices are limited by the inexorable end of a 10-second timer. But choice-making isn’t the place where expression resides in the game. Instead, it comes from anna’s speculations. And in Deadbolt, players are given a framework within which they can reflect and express feelings about others and themselves. The game isn’t about winning or losing, but simply about allowing oneself to be honest and reflective and to share those reflections.

Simulation-Based Play

The last kind of play we’d like to discuss is simulation-based play. Sim City and Rollercoaster Tycoon are well-known examples of this kind of game experience: some aspect of the real world is abstracted into a game, and players get to play “mayor” or “tycoon” within the abstracted interactive model. The Landlord’s Game designed by Elizabeth Magie, which was the origin of a game we know now as Monopoly, is also an example of simulation-based play. Magie designed the game to demonstrate the economic principles of Georgism, an economic system proposed by Henry George. The primary focus of the game was to demonstrate how rents make property owners wealthy and tenants impoverished. Many of us can relate to the way this feels when we are inexorably losing a game of Monopoly to a greedy opponent or becoming that greedy property owner through the luck of a dice roll and some wisely purchased properties.

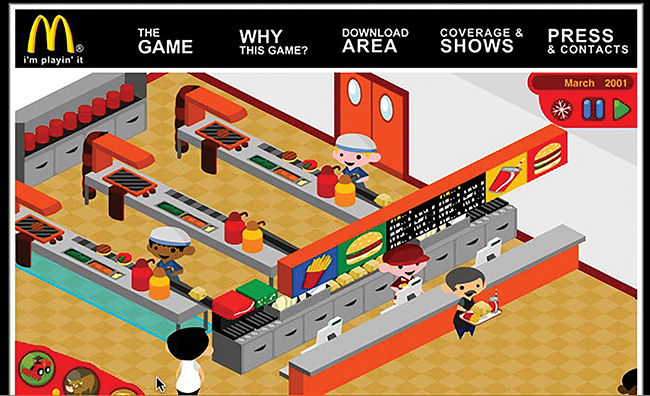

Two independent simulation-based videogames, Molleindustria’s The McDonald’s Videogame and Lucas Pope’s Papers, Please, provide great examples of simulation-based games using the game design tool of abstraction—simplifying the complexity of real-world systems to be playable and accessible in a game.

The McDonald’s Videogame (see Figure 3.23) is a satirical modeling of the McDonald’s fast food restaurant chain and its impact on the people, animals, and environments that come in contact with the company. The game is made up of four interconnected playable models of the McDonald’s ecosystem: a farming simulator that can grow soy beans or cattle; a meat processing plant; a McDonald’s restaurant; and the McDonald’s corporate board room.

Figure 3.23 A screenshot from The McDonald’s Videogame.

The game abstracts the complex systems at play at each level to emphasize the impacts McDonald’s has on its supply chain and the interconnected nature of the company’s business. The farming feeds into the slaughterhouse, which supplies the meat to the restaurants, which in turn produces revenue for the corporation. The game allows players to inhabit this process and play inside the systemic representation of the fast food restaurant. It does so to political ends, to use games and play to make a rhetorical point about the industry.

A different kind of simulation-based play is found in Papers, Please (see Figure 3.24). On the surface, Papers, Please seems like a political game. The player takes on the role of an employee in the Ministry of Admission inspecting passports in the fictional Arstotzka. Each day, the officer is given a set of notices about what to look out for as the applicants are being processed. For example, the player has to make sure that on some days only citizens of Arstotzka are allowed to enter, while on other days, those with valid visas can get in. Through the repetitive actions required to examine and stamp each passport, the game models the experience of someone in a similar kind of job. It also comments upon the seemingly arbitrary nature of government policies around issues that deeply affect people’s lives. Instead of focusing on the larger systemic modeling, Papers, Please emphasizes the particulars of one small part of a larger whole, in the process placing the whole in a new light.

Figure 3.24 A screenshot from Papers, Please.

These two examples show different scales at which we can produce simulations. The McDonald’s Videogame simulates a situation in a holistic yet stylized way, taking into account a large number of factors and presenting them in a simplified top-down model. Papers, Please scales things at a more human scale by putting the player into a more direct role of an individual. The whole can be experienced and contemplated, but in a more granular way. Both of them use point of view—from above or from below—as well as the game design tool of abstraction to help us understand the mechanics of a complex system.

Summary

We’ve looked at a wide range of play styles. There are multiple ways to think about designing games that can produce competition, cooperation, skill, chance, strategy, whimsy, role-playing, performance, expressiveness, and simulation. From a designer’s perspective, these are the basic kinds of games we can create for our players to experience.

Ultimately, game designers should play all sorts of games, regardless of their own tastes. You never know when a randomizing strategy in a free-to-play puzzle game might come in handy for a cooperative role-playing game. The relationships between chance, strategy, skill, simulation, expressiveness, performance, whimsy, role-playing, competition, and cooperation can be recombined in different ways to create new play experiences—like a chef combines different ingredients and cuisines to create new dishes and fusions. The trick is thinking about games as a game designer. Instead of thinking about your own experience, think about what created that experience—what mix of competition or cooperation, of chance and skill, of role-playing or simulation shaped the experience and how these were used in the design of the game that generated it.

![]() Competitive play: A kind of play in which some players will win and some will lose. The kinds of competitive play are player versus player, player versus game, asynchronous competition, symmetrical competition, and asymmetrical competition.

Competitive play: A kind of play in which some players will win and some will lose. The kinds of competitive play are player versus player, player versus game, asynchronous competition, symmetrical competition, and asymmetrical competition.

![]() Cooperative play: Play experience in which players work together to achieve the game’s goals. Cooperative play might include symmetrical cooperation, asymmetrical cooperation, and symbiotic cooperation.

Cooperative play: Play experience in which players work together to achieve the game’s goals. Cooperative play might include symmetrical cooperation, asymmetrical cooperation, and symbiotic cooperation.

![]() Skill-based play: Play that emphasizes player skill development in the pursuit of the game’s goal. Kinds of skill-based play include active skill and mental skill.

Skill-based play: Play that emphasizes player skill development in the pursuit of the game’s goal. Kinds of skill-based play include active skill and mental skill.

![]() Experience-based play: A kind of play focused on providing players with an experience of the game through exploration, unfolding a story, or communal engagement.

Experience-based play: A kind of play focused on providing players with an experience of the game through exploration, unfolding a story, or communal engagement.

![]() Games of chance and uncertainty: Games that ask players to develop strategies to allow for unpredictable moments or aspects of the game. Purely chance-based games remove decision-making from the player experience.

Games of chance and uncertainty: Games that ask players to develop strategies to allow for unpredictable moments or aspects of the game. Purely chance-based games remove decision-making from the player experience.

![]() Whimsical play: A kind of play that emphasizes silly actions, unexpected results, and a sense of euphoria by generating dizziness and a play experience that you need to feel to understand. Whimsical play is often based on silly interactions, constraint as whimsy, and conceptual absurdity.

Whimsical play: A kind of play that emphasizes silly actions, unexpected results, and a sense of euphoria by generating dizziness and a play experience that you need to feel to understand. Whimsical play is often based on silly interactions, constraint as whimsy, and conceptual absurdity.

![]() Role-playing: A game that generates stories through players inhabiting different roles and following a loose set of rules through which all sorts of possibilities can emerge, limited only by players’ imaginations. Types of role-playing story generation include emergent storytelling and progressive storytelling.

Role-playing: A game that generates stories through players inhabiting different roles and following a loose set of rules through which all sorts of possibilities can emerge, limited only by players’ imaginations. Types of role-playing story generation include emergent storytelling and progressive storytelling.

![]() Performative play: A theatrical form of play that generates dramatic action and acting and often includes a good deal of player improvisation. Performative play can generate unintentional performance and conscious performance.

Performative play: A theatrical form of play that generates dramatic action and acting and often includes a good deal of player improvisation. Performative play can generate unintentional performance and conscious performance.

![]() Expressive play: A form of play that often subverts player choice in an effort to clearly express and share something about human experience. Expressive play might involve authorial expression or player expression.

Expressive play: A form of play that often subverts player choice in an effort to clearly express and share something about human experience. Expressive play might involve authorial expression or player expression.

![]() Simulation-based play: A form of play that models a real-world system and presents a point of view (sometimes political, sometimes in terms of a player’s perspective on the world) about that system to the player. Players might engage with a top-down simulation or a bottom-up simulation.

Simulation-based play: A form of play that models a real-world system and presents a point of view (sometimes political, sometimes in terms of a player’s perspective on the world) about that system to the player. Players might engage with a top-down simulation or a bottom-up simulation.

Exercises

1. Choose one of your favorite games and describe it using one or more of the kinds of play described in this chapter: competitive and cooperative play, skill-based play, experience-based play, chance-based play, whimsical play, role-playing, performative play, expressive play, or simulation-based play.

2. Take the game you described in Exercise 1 and try to apply another kind of play to it. What happens when a skill-based game becomes more whimsical? Or simulation based?

3. Turn a competitive game into a cooperative one. How will the rules of the game change? The goal?

4. Choose a game of skill and turn it into a game of experience, or vice versa. How does the game need to be modified to turn it from one type to another?

5. Redesign a game based primarily on chance and uncertainty (Candy Land, roulette) to rely less on chance and include more player choice and strategy. Try to play it with some friends. How is the play experience different?

All materials on the site are licensed Creative Commons Attribution-Sharealike 3.0 Unported CC BY-SA 3.0 & GNU Free Documentation License (GFDL)

If you are the copyright holder of any material contained on our site and intend to remove it, please contact our site administrator for approval.

© 2016-2026 All site design rights belong to S.Y.A.