Java 8 Lambdas (2014)

Chapter 9. Lambda-Enabled Concurrency

I’ve already talked a bit about data parallelism, but in this chapter I’m going to cover how we can use lambda expressions to write concurrent applications that efficiently perform message passing and nonblocking I/O.

Some of the examples in this chapter are written using the Vert.x and RxJava frameworks. The principles are more general, though, and can be used in other frameworks and in your own code without you necessarily needing frameworks at all.

Why Use Nonblocking I/O?

When I introduced parallelism, I talked a lot about trying to use a lot of cores efficiently. That approach is really helpful, but when trying to process a lot of data, it’s not the only threading model that you might want to use.

Let’s suppose you’re trying to write a chat service that handles a very high number of users. Every time a user connects to your service, a TCP connection to your server is opened. If you follow a traditional threading model, every time you want to write some data to your user, you would call a method that sends the user the data. This method call would block the thread that you’re running on.

This approach to I/O, called blocking I/O, is fairly common and fairly easy to understand because the interaction with users follows a normal sequential flow of control through your program. The downside is that when you start looking at scaling your system to a significant number of users, you need to start a significant number of threads on your server in order to service them. That approach just doesn’t scale well.

Nonblocking I/O—or, as it’s sometimes called, asynchronous I/O—can be used to process many concurrent network connections without having an individual thread service each connection. Unlike with blocking I/O, the methods to read and write data to your chat clients return immediately. The actual I/O processing is happening in a separate thread, and you are free to perform some useful work in the meantime. How you choose to use these saved CPU cycles may range from reading more data from another client to ticking over your Minecraft server!

I’ve so far avoided presenting any code to show the ideas because the concept of blocking versus nonblocking I/O can be implemented in a number of different ways in terms of the API. The Java standard library presents a nonblocking I/O API in the form of NIO (New I/O). The original version of NIO uses the concept of a Selector, which lets a thread manage multiple channels of communication, such as the network socket that’s used to write to your chat client.

This approach never proved particularly popular with Java developers and resulted in code that was fairly hard to understand and debug. With the introduction of lambda expressions, it becomes idiomatic to design and develop APIs that don’t have these deficiencies.

Callbacks

To demonstrate the principles of this approach, we’re going to implement a dead simple chat application—no bells and no whistles. In this application, users can send and receive messages to and from each other. They are required to set names for themselves when they first connect.

We’re going to implement the chat application using the Vert.x framework and introduce the necessary techniques as we go along. Let’s start by writing some code that receives TCP connections, as demonstrated in Example 9-1.

Example 9-1. Receiving TCP connections

public class ChatVerticle extends Verticle {

public void start() {

vertx.createNetServer()

.connectHandler(socket -> {

container.logger().info("socket connected");

socket.dataHandler(new User(socket, this));

}).listen(10_000);

container.logger().info("ChatVerticle started");

}

}

You can think of a Verticle as being a bit like a Servlet—it’s the atomic unit of deployment in the Vert.x framework. The entry point to the code is the start method, which is a bit like a main method in a regular Java program. In our chat app, we just use it to set up a server that accepts TCP connections.

We pass in a lambda expression to the connectHandler method, which gets called whenever someone connects to our chat app. This is a callback and works in a similar way to the Swing callbacks I talked about way back in Chapter 1. The benefit of this approach is that the application doesn’t control the threading model—the Vert.x framework can deal with managing threads and all the associated complexity, and all we need to do is think in terms of events and callbacks.

Our application registers another callback using the dataHandler method. This is a callback that gets called whenever some data is read from the socket. In this case, we want to provide more complex functionality, so instead of passing in a lambda expression we use a regular class, User, and let it implement the necessary functional interface. The callback into our User class is listed in Example 9-2.

Example 9-2. Handling user connections

public class User implements Handler<Buffer> {

private static final Pattern newline = Pattern.compile("\\n");

private final NetSocket socket;

private final Set<String> names;

private final EventBus eventBus;

private Optional<String> name;

public User(NetSocket socket, Verticle verticle) {

Vertx vertx = verticle.getVertx();

this.socket = socket;

names = vertx.sharedData().getSet("names");

eventBus = vertx.eventBus();

name = Optional.empty();

}

@Override

public void handle(Buffer buffer) {

newline.splitAsStream(buffer.toString())

.forEach(line -> {

if (!name.isPresent())

setName(line);

else

handleMessage(line);

});

}

// Class continues...

The buffer contains the data that has been written down the network connection to us. We’re using a newline-separated, text-based protocol, so we want to convert this to a String and then split it based upon those newlines.

We have a regular expression to match newline characters, which is a java.util.regex.Pattern instance called newline. Conveniently, Java’s Pattern class has had a splitAsStream method added in Java 8 that lets us split a String using the regular expression and have a stream of values, consisting of the values between each split.

The first thing our users do when they connect to our chat server is set their names. If we don’t know the user’s name, then we delegate to the logic for setting the name; otherwise, we handle our message like a normal chat message.

We also need a way of receiving messages from other users and passing them on to our chat client so the recipients can read them. In order to implement this, at the same time that we set the name of the current user we also register another callback that writes these messages (Example 9-3).

Example 9-3. Registering for chat messages

eventBus.registerHandler(name, (Message<String> msg) -> {

sendClient(msg.body());

});

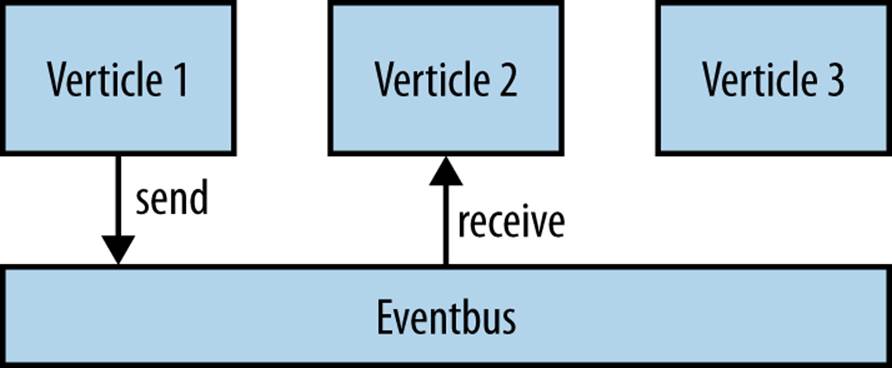

This code is actually taking advantage of Vert.x’s event bus, which allows us to send messages between verticles in a nonblocking fashion (see Figure 9-1). The registerHandler method allows us to associate a handler with a certain address, so when a message is sent to that address the handler gets called with the message as its argument. Here we use the username as the address.

Figure 9-1. Event bus sending

By registering handlers at addresses and sending messages to them, it’s possible to build up very sophisticated and/or decoupled sets of services that react in an entirely nonblocking fashion. Note that within our design, we share no state.

Vert.x’s event bus lets us send a variety of types of message over it, but all of them will be wrapped in a Message object. Point-to-point messaging is available through the Message objects themselves; they may hold a reply handler for the sender of the Message object. Because in this case we want the actual body of the message—that is, the text itself—we just called the body method. We’ll send this text message to the receiving user’s chat client, implemented by writing the message down the TCP connection.

When our application wants to send a message from one user to another, it sends that message to the address that represents the other user (Example 9-4). Again, this is that user’s username.

Example 9-4. Sending chat messages

eventBus.send(user, name.get() + '>' + message);

Let’s extend this very basic chat server to broadcast messages and followers. There are two new commands that we need to implement in order for this to work:

§ An exclamation mark representing the broadcast command, which sends all of its following text to any following users. For example, if bob typed “!hello followers”, then all of his followers would receive “bob>hello followers”.

§ The follow command, which follows a specified user suffixed to the command, as in “follow bob”.

Once we’ve parsed out the commands, we’re going to implement the broadcastMessage and followUser methods, which correspond to each of these commands.

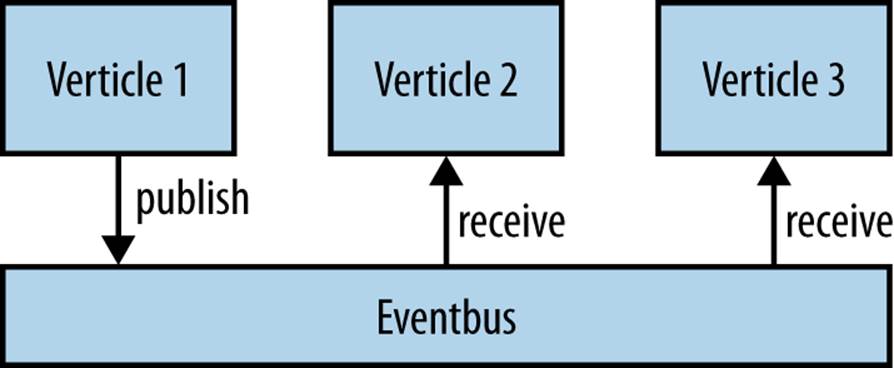

There’s a different pattern of communication here as well. Instead of just having to send messages to a single user, you now have the ability to publish to multiple users. Fortunately, Vert.x’s event bus also lets us publish a message to multiple handlers (see Figure 9-2). This lets us use a similar overarching approach.

Figure 9-2. Event bus publishing

The only code difference is that we use the publish method on the event bus rather than the send method. To avoid overlapping with the existing addresses whenever a user uses the ! command, it gets published to the user’s name suffixed with .followers. So, for example, when bob publishes a message it goes to any handler registered on bob.followers (Example 9-5).

Example 9-5. Broadcasting messages to followers

private void broadcastMessage(String message) {

String name = this.name.get();

eventBus.publish(name + ".followers", name + '>' + message);

}

When it comes to the handler, we want to do the same operation that we performed earlier when registering sends: pass that message along to the client (Example 9-6).

Example 9-6. Receiving the broadcast messages

private void followUser(String user) {

eventBus.registerHandler(user + ".followers", (Message<String> message) -> {

sendClient(message.body());

});

}

NOTE

If you send to an address and there are multiple handlers listening on that address, a round-robin selector is used to decide which handler receives your message. This means that you need to be a bit careful when registering addresses.

Message Passing Architectures

What I’ve been describing here is a message passing–based architecture that I’ve implemented using a simple chat client. The details of the chat client are much less important than the overall pattern, so let’s talk about message passing itself.

The first thing to note is that this is a no-shared-state design. All communication between our verticles is done by sending messages over our event bus. This means that we don’t need to protect any shared state, so we don’t need any kind of locks or use of the synchronized keyword in our code base at all. Concurrency is much simpler.

In order to ensure that we aren’t sharing any state between verticles, we’ve actually imposed a few constraints on the types of messages being sent over the event bus. The example messages that we passed over the event bus in this case were plain old Java strings. These are immutable by design, which means that we can safely send them between verticles. Because the receiving handler can’t modify the state of the String, it can’t interfere with the behavior of the sender.

Vert.x doesn’t restrict us to sending strings as messages, though; we can use more complex JSON objects or even build our own binary messages using the Buffer class. These aren’t immutable messages, which means that if we just naively passed them around, our message senders and message handlers could share state by writing or reading through these messages.

The Vert.x framework avoids this problem by copying any mutable message the moment that you send it. That way the receiver gets the correct value, but you still aren’t sharing state. Regardless of whether you’re using the Vert.x framework, it’s really important that you don’t let your messages be an accidental source of shared state. Completely immutable messages are the simplest way of doing this, but copying the message also solves the problem.

The verticle model of development also lets us implement a concurrent system that is easy to test. This is because each verticle can be tested in isolation by sending messages in and expecting results to be returned. We can then compose a complex system out of individually tested components without incurring as many problems in integrating the components as we would if they were communicating via shared mutable state. Of course, end-to-end tests are still useful for making sure that your system does what your users expect of it!

Message passing–based systems also make it easier to isolate failure scenarios and write reliable code. If there is an error within a message handler, we have the choice of restarting its local verticle without having to restart the entire JVM.

In Chapter 6, we looked at how you can use lambda expressions in conjunction with the streams library in order to build data parallel code. That lets us use parallelism in order to process large amounts of data faster. Message passing and reactive programming, which we’ll look at later in this chapter, are at the other end of the spectrum. We’re looking at concurrency situations in which we want to have many more units of I/O work, such as connected chat clients, than we have threads running in parallel. In both cases, the solution is the same: use lambda expressions to represent the behavior and build APIs that manage the concurrency for you. Smarter libraries mean simpler application code.

The Pyramid of Doom

You’ve seen how we can use callbacks and events to produce nonblocking concurrent code, but I haven’t mentioned the elephant in the room. If you write code with lots of callbacks, it becomes very hard to read, even with lambda expressions. Let’s take a look at a more concrete example in order to understand this problem better.

While developing the chat server I wrote a series of tests that described the behavior of the verticle from the point of view of the client. The code for this is listed in the messageFriend test in Example 9-7.

Example 9-7. A test of whether two friends in our chat server can talk to each other

@Test

public void messageFriend() {

withModule(() -> {

withConnection(richard -> {

richard.dataHandler(data -> {

assertEquals("bob>oh its you!", data.toString());

moduleTestComplete();

});

richard.write("richard\n");

withConnection(bob -> {

bob.dataHandler(data -> {

assertEquals("richard>hai", data.toString());

bob.write("richard<oh its you!");

});

bob.write("bob\n");

vertx.setTimer(6, id -> richard.write("bob<hai"));

});

});

});

}

I connect two clients, richard and bob, then richard says “hai” to bob and bob replies “oh it’s you!” I’ve refactored out common code to make a connection, but even then you’ll notice that the nested callbacks are beginning to turn into a pyramid of doom. They are stretching rightward across the screen, a bit like a pyramid sitting on its side (don’t look at me—I didn’t come up with the name!). This is a pretty well known antipattern, which makes it hard for a user to read and understand the code. It also stretches the logic of the code between multiple methods.

In the last chapter, I discussed how we could use lambda expressions to manage resources by passing a lambda expression into a with method. You’ll notice in this test that I’ve used this pattern in couple of places. We’ve got a withModule method that deploys the current Vert.x module, runs some code, and shuts the module down. We’ve also got a withConnection method that connects to the ChatVerticle and then closes down the connection when it’s done with it.

The benefit of using these with method calls here rather than using try-with-resources is that they fit into the nonblocking threading model that we’re using in this chapter. We can try and refactor this code a bit in order to make it easier to understand, as in Example 9-8.

Example 9-8. A test of whether two friends in our chat server can talk to each other, split into different methods

@Test

public void canMessageFriend() {

withModule(this::messageFriendWithModule);

}

private void messageFriendWithModule() {

withConnection(richard -> {

checkBobReplies(richard);

richard.write("richard\n");

messageBob(richard);

});

}

private void messageBob(NetSocket richard) {

withConnection(messageBobWithConnection(richard));

}

private Handler<NetSocket> messageBobWithConnection(NetSocket richard) {

return bob -> {

checkRichardMessagedYou(bob);

bob.write("bob\n");

vertx.setTimer(6, id -> richard.write("bob<hai"));

};

}

private void checkRichardMessagedYou(NetSocket bob) {

bob.dataHandler(data -> {

assertEquals("richard>hai", data.toString());

bob.write("richard<oh its you!");

});

}

private void checkBobReplies(NetSocket richard) {

richard.dataHandler(data -> {

assertEquals("bob>oh its you!", data.toString());

moduleTestComplete();

});

}

The aggressive refactoring in Example 9-8 has solved the pyramid of doom problem, but at the expense of splitting up the logic of the single test into several methods. Instead of one method having a single responsibility, we have several sharing a responsibility between them! Our code is still hard to read, just for a different reason.

The more operations you want to chain or compose, the worse this problem gets. We need a better solution.

Futures

Another option when trying to build up complex sequences of concurrent operations is to use what’s known as a Future. A Future is an IOU for a value. Instead of a method returning a value, it returns the Future. The Future doesn’t have the value when it’s first created, but it can be exchanged for the value later on, like an IOU.

You extract the value of the Future by calling its get method, which blocks until the value is ready. Unfortunately, Futures end up with composability issues, just like callbacks. We’ll take a quick look at the issues that you can encounter.

The scenario we’ll be considering is looking up information about an Album from some external web services. We need to find the list of tracks associated with a given Album and also a list of artists. We also need to ensure that we have sufficient credentials to access each of the services. So we need to log in, or at least make sure that we’re already logged in.

Example 9-9 is an implementation of this problem using the existing Future API. We start out at ![]() by logging into the track and artist services. Each of these login actions returns a Future<Credentials> object with the login information. The Future interface is generic, soFuture<Credentials> can be read as an IOU for a Credentials object.

by logging into the track and artist services. Each of these login actions returns a Future<Credentials> object with the login information. The Future interface is generic, soFuture<Credentials> can be read as an IOU for a Credentials object.

Example 9-9. Downloading album information from some external web services using Futures

@Override

public Album lookupByName(String albumName) {

Future<Credentials> trackLogin = loginTo("track"); ![]()

Future<Credentials> artistLogin = loginTo("artist");

try {

Future<List<Track>> tracks = lookupTracks(albumName, trackLogin.get()); ![]()

Future<List<Artist>> artists = lookupArtists(albumName, artistLogin.get());

return new Album(albumName, tracks.get(), artists.get()); ![]()

} catch (InterruptedException | ExecutionException e) {

throw new AlbumLookupException(e.getCause()); ![]()

}

}

At ![]() we make our calls to look up the tracks and artists given the login credentials and call get on both of these login credentials in order to get them out of the Futures. At

we make our calls to look up the tracks and artists given the login credentials and call get on both of these login credentials in order to get them out of the Futures. At ![]() we build up our new Album to return, again calling get in order to block on the existing Futures. If there’s an exception, it gets thrown, so we have to propagate it through a domain exception at

we build up our new Album to return, again calling get in order to block on the existing Futures. If there’s an exception, it gets thrown, so we have to propagate it through a domain exception at ![]() .

.

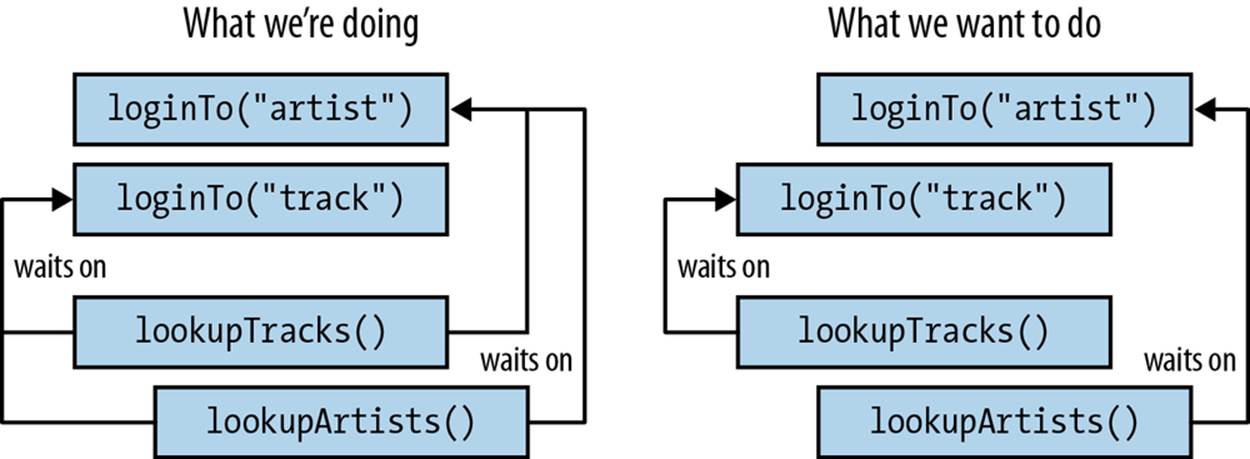

As you’ll have noticed, if you want to pass the result of one Future into the beginning of another piece of work, you end up blocking the thread of execution. This can be become a performance limitation because instead of work being executed in parallel it is (accidentally) run in serial.

What this means in the case of Example 9-9 is that we can’t start either of the calls to the lookup services until we’ve logged into both of them. This is pretty unnecessary: lookupTracks only needs its login credentials, and lookupArtists should only need to wait for its login credentials. The breakdown of which actions need to wait for others to complete is shown in Figure 9-3.

We could take the blocking get calls and drag them down into the execution body of lookupTracks and lookupArtists. This would solve the problem, but would also result in uglier code and an inability to reuse credentials between multiple calls.

Figure 9-3. Both lookup actions don’t need to wait for both login actions

What we really want here is a way of acting on the result of a Future, without having to make a blocking get call. We want to combine a Future with a callback.

Completable Futures

The solution to these issues arrives in the form of the CompletableFuture. This combines the IOU idea of a Future with using callbacks to handle event-driven work. The key point about the CompletableFuture is that you can compose different instances in a way that doesn’t result in the pyramid of doom.

NOTE

You might have encountered the concept behind the CompletableFuture before; various other languages call them a deferred object or a promise. In the Google Guava Library and the Spring Framework these are referred to as ListenableFutures.

I’ll illustrate some usage scenarios by rewriting Example 9-9 to use CompletableFuture, rather than Future, as in Example 9-10.

Example 9-10. Downloading album information from some external web services using CompletableFutures

public Album lookupByName(String albumName) {

CompletableFuture<List<Artist>> artistLookup

= loginTo("artist")

.thenCompose(artistLogin -> lookupArtists(albumName, artistLogin)); ![]()

return loginTo("track")

.thenCompose(trackLogin -> lookupTracks(albumName, trackLogin)) ![]()

.thenCombine(artistLookup, (tracks, artists)

-> new Album(albumName, tracks, artists)) ![]()

.join(); ![]()

}

In Example 9-10 loginTo, lookupArtists, and lookupTracks all return a CompletableFuture instead of a Future. The key “trick” to the CompletableFuture API is to register lambda expressions and chain higher-order functions. The methods are different, but the concept is incredibly similar to the Streams API design.

At ![]() we use the thenCompose method to transform our Credentials into a CompletableFuture that contains the artists. This is a bit like taking an IOU for money from a friend and spending the money on Amazon when you get it. You don’t immediately get a new book—you just get an email from Amazon saying that your book is on its way: a different form of IOU.

we use the thenCompose method to transform our Credentials into a CompletableFuture that contains the artists. This is a bit like taking an IOU for money from a friend and spending the money on Amazon when you get it. You don’t immediately get a new book—you just get an email from Amazon saying that your book is on its way: a different form of IOU.

At ![]() we again use thenCompose and the Credentials from our Track API login in order to generate a CompletableFuture of tracks. We introduce a new method, thenCombine, at

we again use thenCompose and the Credentials from our Track API login in order to generate a CompletableFuture of tracks. We introduce a new method, thenCombine, at ![]() . This takes the result from a CompletableFuture and combines it with anotherCompletableFuture. The combining operation is provided by the end user as a lambda expression. We want to take our tracks and artists and build up an Album object, so that’s what we do.

. This takes the result from a CompletableFuture and combines it with anotherCompletableFuture. The combining operation is provided by the end user as a lambda expression. We want to take our tracks and artists and build up an Album object, so that’s what we do.

At this point, it’s worth reminding yourself that just like with the Streams API, we’re not actually doing things; we’re building up a recipe that says how to do things. Our method can’t guarantee that the CompletableFuture has completed until one of the final methods is called. BecauseCompletableFuture implements Future, we could just call the get method again. CompletableFuture contains the join method, which is called at ![]() and does the same job. It doesn’t have a load of the nasty checked exceptions that hindered our use of get.

and does the same job. It doesn’t have a load of the nasty checked exceptions that hindered our use of get.

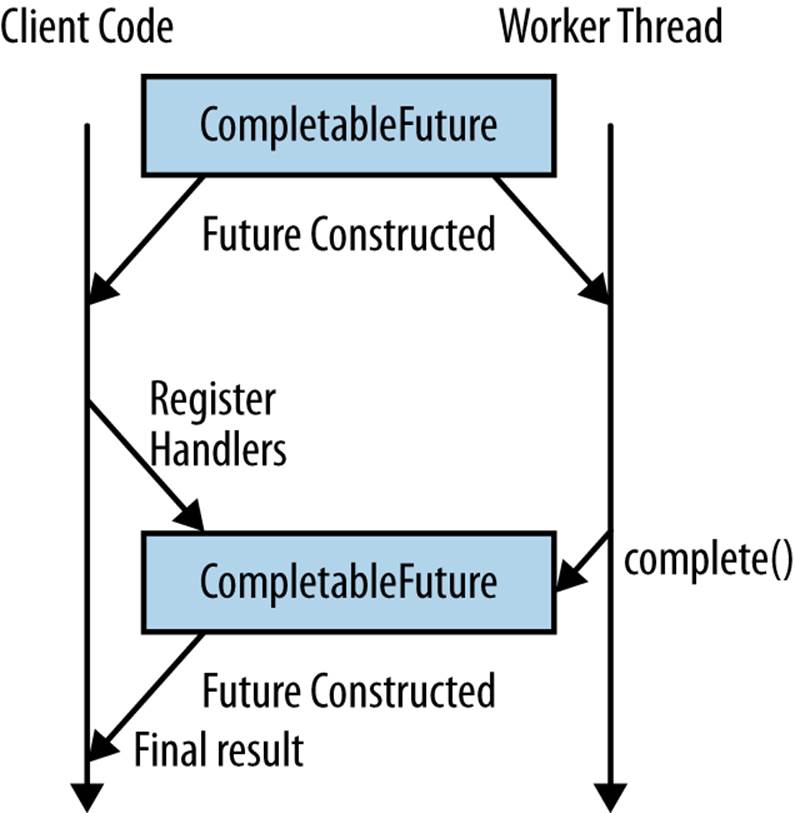

You’ve probably got the basic idea of how to use CompletableFuture, but creating them is another matter. There are two different aspects of creating a CompletableFuture: creating the object itself and actually completing it by giving it the value that it owes its client code.

As Example 9-11 shows, it’s pretty easy to create a CompletableFuture object. You just call its constructor! This object can now be handed out to client code for chaining operations. We also keep a reference to this object in order to process the work on another thread.

Example 9-11. Completing a future by providing a value

CompletableFuture<Artist> createFuture(String id) {

CompletableFuture<Artist> future = new CompletableFuture<>();

startJob(future);

return future;

}

Once we’ve performed the work that needs to be done on whatever thread we’re using, we need to tell the CompletableFuture what value it represents. Remember that this work can by done through a number of different threading models. For example, we can submit a task to anExecutorService, use an event loop-based system such as Vert.x, or just spin up a Thread and do work on it. As shown in Example 9-12, in order to tell the CompletableFuture that it’s ready, you call the complete method. It’s time to pay back the IOU.

Example 9-12. Completing a future by providing a value

future.complete(artist);

Figure 9-4. A completable future is an IOU that can be processed by handlers

Of course, a very common usage of CompletableFuture is to asynchronously run a block of code. This code completes and returns a value. In order to avoid lots of people having to implement the same code over and over again, there is a useful factory method for creating aCompletableFuture, shown in Example 9-13, called supplyAsync.

Example 9-13. Example code for asynchronously creating a CompletableFuture

CompletableFuture<Track> lookupTrack(String id) {

return CompletableFuture.supplyAsync(() -> {

// Some expensive work is done here ![]()

// ...

return track; ![]()

}, service); ![]()

}

The supplyAsync method takes a Supplier that gets executed. The key point, shown at ![]() , is that this Supplier can do some time-consuming work without blocking the current thread—thus the Async in the method name. The value returned at

, is that this Supplier can do some time-consuming work without blocking the current thread—thus the Async in the method name. The value returned at ![]() is used to complete theCompletableFuture. At

is used to complete theCompletableFuture. At ![]() we provide an Executor, called service, that tells the CompletableFuture where to perform the work. If no Executor is provided, it just uses the same fork/join thread pool that parallel streams execute on.

we provide an Executor, called service, that tells the CompletableFuture where to perform the work. If no Executor is provided, it just uses the same fork/join thread pool that parallel streams execute on.

Of course, not every IOU has a happy ending. Sometimes we encounter exceptional circumstances and can’t pay our debts. As Example 9-14 demonstrates, the CompletableFuture API accounts for these situations by letting you completeExceptionally. This can be called as an alternative to complete. You shouldn’t call both complete and completeExceptionally on a CompletableFuture, though.

Example 9-14. Completing a future if there’s an error

future.completeExceptionally(new AlbumLookupException("Unable to find " + name));

A complete investigation of the CompletableFuture API is rather beyond the scope of this chapter, but in many ways it is a hidden goodie bag. There are quite a few useful methods in the API for composing and combining different instances of CompletableFuture in pretty much any way imaginable. Besides, by now you should be familiar with the fluent style of chaining sequences of higher-order functions to tell the computer what to do.

Let’s take a brief look at a few of those use cases:

§ If you want to end your chain with a block of code that returns nothing, such as a Consumer or Runnable, then take a look at thenAccept and thenRun.

§ Transforming the value of the CompletableFuture, a bit like using the map method on Stream, can be achieved using thenApply.

§ If you want to convert situations in which your CompletableFuture has completed with an exception, the exceptionally method allows you to recover by registering a function to make an alternative value.

§ If you need to do a map that takes account of both the exceptional case and regular use cases, use handle.

§ When trying to figure out what is happening with your CompletableFuture, you can use the isDone and isCompletedExceptionally methods.

CompletableFuture is really useful for building up concurrent work, but it’s not the only game in town. We’re now going to look at a related concept that offers a bit more flexibility in exchange for more complex code.

Reactive Programming

The concept behind a CompletableFuture can be generalized from single values to complete streams of data using reactive programming. Reactive programming is actually a form of declarative programming that lets us program in terms of changes and data flows that get automatically propagated.

You can think of a spreadsheet as a commonly used example of reactive programming. If you enter =B1+5 in cell C1, it tells the spreadsheet to add 5 to the contents of cell B1 and put the result in C1. In addition, the spreadsheet reacts to any future changes in B1 and updates the value in C1.

The RxJava library is a port of these reactive ideas onto the JVM. We won’t be going into the library in huge amounts of depth here, just covering the key concepts.

RxJava introduces a class called Observable that represents a sequence of events that you can react to. It’s an IOU for a sequence. There is a strong connection between an Observable and the Stream interface that we encountered in Chapter 3.

In both cases we build up recipes for performing work by chaining higher-order functions and use lambda expressions in order to associate behavior with these general operations. In fact, many of the operations defined on an Observable are the same as on a Stream: map, filter,reduce.

The big difference between the approaches is the use case. Streams are designed to build up computational workflows over in-memory collections. RxJava, on the other hand, is designed to compose and sequence asynchronous and event-based systems. Instead of pulling data out, it gets pushed in. Another way of thinking about RxJava is that it is to a sequence of values what a CompletableFuture is to a single value.

Our concrete example this time around is searching for an artist and is shown in Example 9-15. The search method filters the results by name and nationality. It keeps a local cache of artist names but must look up other artist information, such as nationality, from external services.

Example 9-15. Searching for an artist by name and nationality

public Observable<Artist> search(String searchedName,

String searchedNationality,

int maxResults) {

return getSavedArtists() ![]()

.filter(name -> name.contains(searchedName)) ![]()

.flatMap(this::lookupArtist) ![]()

.filter(artist -> artist.getNationality() ![]()

.contains(searchedNationality))

.take(maxResults); ![]()

}

At ![]() we get an Observable of the saved artist names. The higher-order functions on the Observable class are similar to those on the Stream interface, so at

we get an Observable of the saved artist names. The higher-order functions on the Observable class are similar to those on the Stream interface, so at ![]() and

and ![]() we’re able to filter by artist name and nationality, in a similar manner as if we were using a Stream.

we’re able to filter by artist name and nationality, in a similar manner as if we were using a Stream.

At ![]() we replace each name with its Artist object. If this were as simple as calling its constructor, we would obviously use the map operation. But in this case we need to compose a sequence of calls to external web services, each of which may be done in its own thread or on a thread pool. Consequently, we need to replace each name with an Observable representing one or more artists. So we use the flatMap operation.

we replace each name with its Artist object. If this were as simple as calling its constructor, we would obviously use the map operation. But in this case we need to compose a sequence of calls to external web services, each of which may be done in its own thread or on a thread pool. Consequently, we need to replace each name with an Observable representing one or more artists. So we use the flatMap operation.

We also need to limit ourselves to maxResults number of results in our search. To implement this at ![]() , we call the take method on Observable.

, we call the take method on Observable.

As you can see, the API is quite stream-like in usage. The big difference is that while a Stream is designed to compute final results, the RxJava API acts more like CompletableFuture in its threading model.

In CompletableFuture we had to pay the IOU by calling complete with a value. Because an Observable represents a stream of events, we need the ability to push multiple values; Example 9-16 shows how to do this.

Example 9-16. Pushing values into an Observable and completing it

observer.onNext("a");

observer.onNext("b");

observer.onNext("c");

observer.onCompleted();

We call onNext repeatedly, once for each element in the Observable. We can do this in a loop and on whatever thread of execution we want to produce the values from. Once we have finished with whatever work is needed to generate the events, we call onCompleted to signal the end of the Observable. As well as the full-blown streaming approach, there are also several static convenience factory methods for creating Observable instances from futures, iterables, and arrays.

In a similar manner to CompletableFuture, the Observable API also allows for finishing with an exceptional event. We can use the onError method, shown in Example 9-17, in order to signal an error. The functionality here is a little different from CompletableFuture—you can still get all the events up until an exception occurs, but in both cases you either end normally or end exceptionally.

Example 9-17. Notifying your Observable that an error has occurred

observer.onError(new Exception());

As with CompletableFuture, I’ve only given a flavor of how and where to use the Observable API here. If you want more details, read the project’s comprehensive documentation. RxJava is also beginning to be integrated into the existing ecosystem of Java libraries. The enterprise integration framework Apache Camel, for example, has added a module called Camel RX that gives the ability to use RxJava with its framework. The Vert.x project has also started a project to Rx-ify its API.

When and Where

Throughout this chapter, I’ve talked about how to use nonblocking and event-based systems. Is that to say that everyone should just go out tomorrow and throw away their existing Java EE or Spring enterprise web applications? The answer is most definitely no.

Even accounting for CompletableFuture and RxJava being relatively new, there is still an additional level of complexity when using these idioms. They’re simpler than using explicit futures and callbacks everywhere, but for many problems the traditional blocking web application development is just fine. If it ain’t broke, don’t fix it.

Of course, that’s not to say that reading this chapter was a waste of your afternoon! Event-driven, reactive applications are growing in popularity and are frequently a great way to model the problems in your domain. The Reactive Manifesto advocates building more applications in this style, and if it’s right for you, then you should. There are two scenarios in particular in which you might want to think in terms of reacting to events rather than blocking.

The first is when your business domain is phrased in terms of events. A classic example here is Twitter, a service for subscribing to streams of text messages. Your users are sending messages between one another, so by making your application event-driven, you are accurately modeling the business domain. Another example might be an application that tries to plot the price of shares. Each new price update can be modeled as an event.

The second obvious use case is a situation where your application needs to perform many I/O operations simultaneously. In these situations, performing blocking I/O requires too many threads to be spawned simultaneously. This results in too many locks in contention and too much context switching. If you want to deal with thousands of concurrent connections or more, it’s usually better to go nonblocking.

Key Points

§ Event-driven architectures are easy to implement using lambda-based callbacks.

§ A CompletableFuture represents an IOU for a value. They can be easily composed and combined using lambdas.

§ An Observable extends the idea of a CompletableFuture to streams of data.

Exercises

There’s really only one exercise for this chapter, and it requires refactoring some code to use a CompletableFuture. We’ll start out with the BlockingArtistAnalyzer class shown in Example 9-18. This class takes the names of two artists, looks up the Artist objects from the names, and returns true if the first artist has more members and false otherwise. It is injected with an artistLookupService that may take some time to look up the Artist in question. Because BlockingArtistAnalyzer blocks on this service twice sequentially, the analyzer can be slow; the goal of our exercise is to speed it up.

Example 9-18. The BlockingArtistAnalyzer tells its clients which Artist has more members

public class BlockingArtistAnalyzer {

private final Function<String, Artist> artistLookupService;

public BlockingArtistAnalyzer(Function<String, Artist> artistLookupService) {

this.artistLookupService = artistLookupService;

}

public boolean isLargerGroup(String artistName, String otherArtistName) {

return getNumberOfMembers(artistName) > getNumberOfMembers(otherArtistName);

}

private long getNumberOfMembers(String artistName) {

return artistLookupService.apply(artistName)

.getMembers()

.count();

}

}

The first part of this exercise is to refactor the blocking return code to use a callback interface. In this case, we’ll be using a Consumer<Boolean>. Remember that Consumer is a functional interface that ships with the JVM that accepts a value and returns void. Your mission, should you choose to accept it, is to alter BlockingArtistAnalyzer so that it implements ArtistAnalyzer (Example 9-19).

Example 9-19. The ArtistAnalyzer that you need to make BlockingArtistAnalyzer implement

public interface ArtistAnalyzer {

public void isLargerGroup(String artistName,

String otherArtistName,

Consumer<Boolean> handler);

}

Now that we have an API that fits into the callback model, we can remove the need for both of the blocking lookups to happen at the same time. You should refactor the isLargerGroup method so that they can operate concurrently using the CompletableFuture class.