Java 8 Lambdas (2014)

Chapter 8. Design and Architectural Principles

The critical design tool for software development is a mind well educated in design principles. It is not…technology.

— Craig Larman

I’ve already established that lambda expressions are a fairly simple change to the Java language and that there are a bunch of ways that we can use them within the standard JDK libraries. Most Java code isn’t written by the core JDK developers—it’s written by people like you. In order to use lambda expressions in the most beneficial way possible, you need to start introducing them into your existing code base. They are just another tool in the belt of a professional Java developer, no different from an interface or a class.

In this chapter, we’re going to explore how to use to use lambda expressions to implement the SOLID principles that provide guidelines toward good object-oriented programming. There are also many existing design patterns that can be improved by the use of lambda expressions, and we’ll take a look at a smattering of those.

When coding with teammates at work, I’m sure you’ve come across a situation where you’ve implemented some feature or fixed a bug, and you were pretty happy with the way that you had done it, but soon after someone else took a look at the same code—perhaps during a code review—and they weren’t so happy with it! It’s pretty common to have this kind of disagreement over what really constitutes good code or bad code.

Most of the time when people are disagreeing, they are pushing a matter of opinion. The reviewer would have done it another way. It’s not necessarily that he is right or wrong, or that you are right or wrong. When you welcome lambdas into your life, there’s another topic to think about. It’s not that they are a difficult feature or a big point of contention as much as they are just another design issue that people can discuss or disagree on.

This chapter is here to help! I’ll try to put forth some well-grounded principles and patterns upon which you can compose maintainable and reliable software—not just to use the shiny new JDK libraries, but to use lambda expressions in your own domain architecture and applications.

Lambda-Enabled Design Patterns

One of the other bastions of design we’re all familiar with is the idea of design patterns. Patterns document reusable templates that solve common problems in software architecture. If you spot a problem and you’re familiar with an appropriate pattern, then you can take the pattern and apply it to your situation. In a sense, patterns codify what people consider to be a best-practice approach to a given problem.

Of course, no practice is ever the best practice forever. A common example is the once-popular singleton pattern, which enforces the creation of only one instance of an object. Over the last decade, this has been roundly criticized for making applications more brittle and harder to test. As the Agile software movement has made testing of applications more important, the issues with the singleton pattern have made it an antipattern: a pattern you should never use.

In this section, I’m not going to talk about how patterns have become obsolete. We’re instead going to look at how existing design patterns have become better, simpler, or in some cases implementable in a different way. In all cases, the language changes in Java 8 are the driving factor behind the pattern changing.

Command Pattern

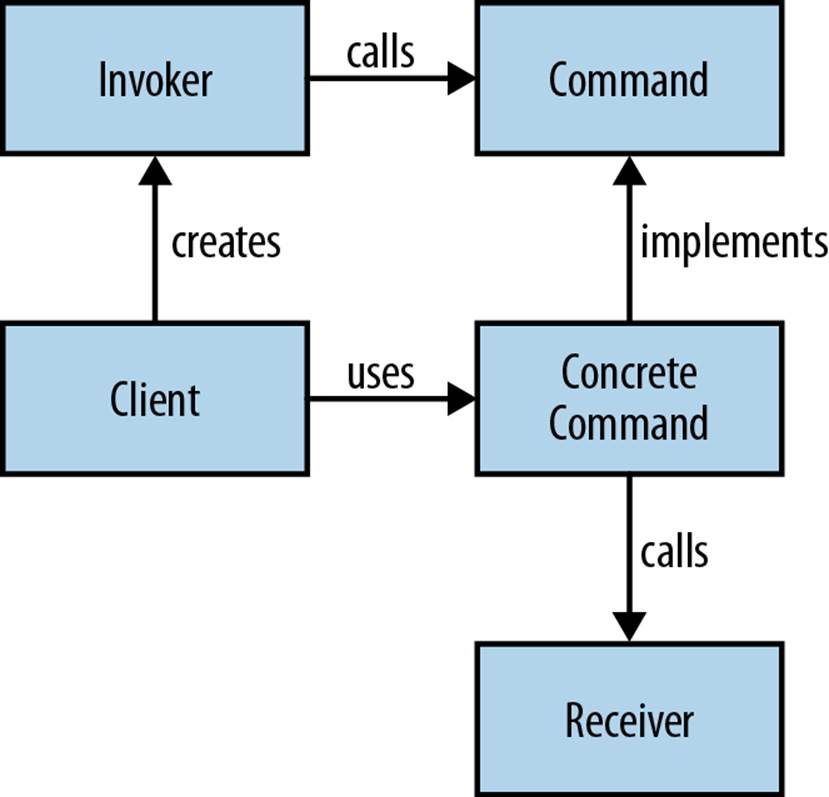

A command object is an object that encapsulates all the information required to call another method later. The command pattern is a way of using this object in order to write generic code that sequences and executes methods based on runtime decisions. There are four classes that take part in the command pattern, as shown in Figure 8-1:

Receiver

Performs the actual work

Command

Encapsulates all the information required to call the receiver

Invoker

Controls the sequencing and execution of one or more commands

Client

Creates concrete command instances

Figure 8-1. The command pattern

Let’s look at a concrete example of the command pattern and see how it improves with lambda expressions. Suppose we have a GUI Editor component that has actions upon it that we’ll be calling, such as open or save, like in Example 8-1. We want to implement macro functionality—that is, a series of operations that can be recorded and then run later as a single operation. This is our receiver.

Example 8-1. Common functions a text editor may have

public interface Editor {

public void save();

public void open();

public void close();

}

In this example, each of the operations, such as open and save, are commands. We need a generic command interface to fit these different operations into. I’ll call this interface Action, as it represents performing a single action within our domain. This is the interface that all our command objects implement (Example 8-2).

Example 8-2. All our actions implement the Action interface

public interface Action {

public void perform();

}

We can now implement our Action interface for each of the operations. All these classes need to do is call a single method on our Editor and wrap this call into our Action interface. I’ll name the classes after the operations that they wrap, with the appropriate class naming convention—so, the save method corresponds to a class called Save. Examples 8-3 and 8-4 are our command objects.

Example 8-3. Our save action delegates to the underlying method call on Editor

public class Save implements Action {

private final Editor editor;

public Save(Editor editor) {

this.editor = editor;

}

@Override

public void perform() {

editor.save();

}

}

Example 8-4. Our open action also delegates to the underlying method call on Editor

public class Open implements Action {

private final Editor editor;

public Open(Editor editor) {

this.editor = editor;

}

@Override

public void perform() {

editor.open();

}

}

Now we can implement our Macro class. This class can record actions and run them as a group. We use a List to store the sequence of actions and then call forEach in order to execute each Action in turn. Example 8-5 is our invoker.

Example 8-5. A macro consists of a sequence of actions that can be invoked in turn

public class Macro {

private final List<Action> actions;

public Macro() {

actions = new ArrayList<>();

}

public void record(Action action) {

actions.add(action);

}

public void run() {

actions.forEach(Action::perform);

}

}

When we come to build up a macro programmatically, we add an instance of each command that has been recorded to the Macro object. We can then just run the macro and it will call each of the commands in turn. As a lazy programmer, I love the ability to define common workflows as macros. Did I say “lazy”? I meant focused on improving my productivity. The Macro object is our client code and is shown in Example 8-6.

Example 8-6. Building up a macro with the command pattern

Macro macro = new Macro();

macro.record(new Open(editor));

macro.record(new Save(editor));

macro.record(new Close(editor));

macro.run();

How do lambda expressions help? Actually, all our command classes, such as Save and Open, are really just lambda expressions wanting to get out of their shells. They are blocks of behavior that we’re creating classes in order to pass around. This whole pattern becomes a lot simpler with lambda expressions because we can entirely dispense with these classes. Example 8-7 shows how to use our Macro class without these command classes and with lambda expressions instead.

Example 8-7. Using lambda expressions to build up a macro

Macro macro = new Macro();

macro.record(() -> editor.open());

macro.record(() -> editor.save());

macro.record(() -> editor.close());

macro.run();

In fact, we can do this even better by recognizing that each of these lambda expressions is performing a single method call. So, we can actually use method references in order to wire the editor’s commands to the macro object (see Example 8-8).

Example 8-8. Using method references to build up a macro

Macro macro = new Macro();

macro.record(editor::open);

macro.record(editor::save);

macro.record(editor::close);

macro.run();

The command pattern is really just a poor man’s lambda expression to begin with. By using actual lambda expressions or method references, we can clean up the code, reducing the amount of boilerplate required and making the intent of the code more obvious.

Macros are just one example of how we can use the command pattern. It’s frequently used in implementing component-based GUI systems, undo functions, thread pools, transactions, and wizards.

NOTE

There is already a functional interface with the same structure as our interface Action in core Java—Runnable. We could have chosen to use that in our macro class, but in this case it seemed more appropriate to consider an Action to be part of the vocabulary of our domain and create our own interface.

Strategy Pattern

The strategy pattern is a way of changing the algorithmic behavior of software based upon a runtime decision. How you implement the strategy pattern depends upon your circumstances, but in all cases the main idea is to be able to define a common problem that is solved by different algorithms and then encapsulate all the algorithms behind the same programming interface.

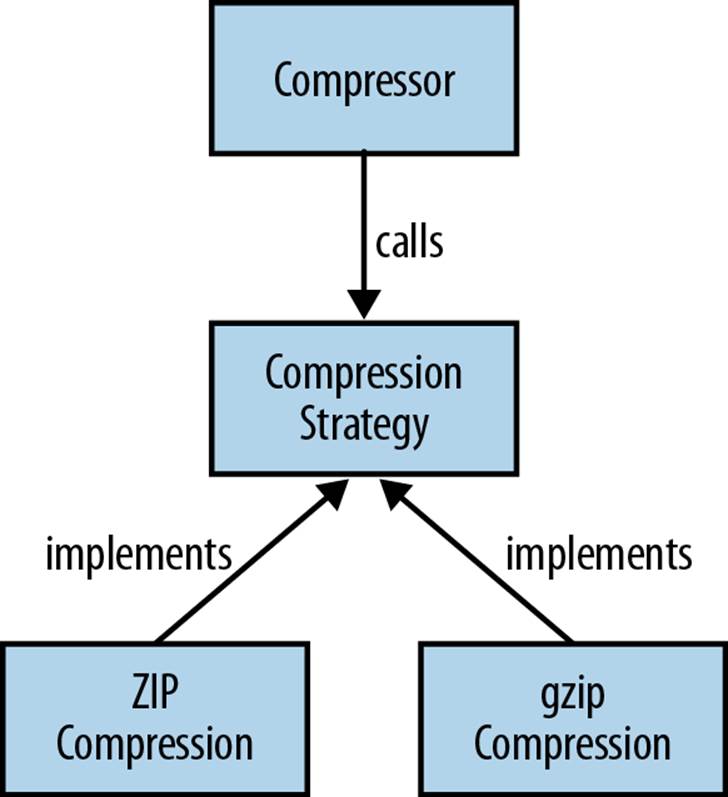

An example algorithm we might want to encapsulate is compressing files. We’ll give our users the choice of compressing our files using either the zip algorithm or the gzip algorithm and implement a generic Compressor class that can compress using either algorithm.

First we need to define the API for our strategy (see Figure 8-2), which I’ll call CompressionStrategy. Each of our compression algorithms will implement this interface. They have the compress method, which takes and returns an OutputStream. The returned OutputStream is a compressed version of the input (see Example 8-9).

Figure 8-2. The strategy pattern

Example 8-9. Defining a strategy interface for compressing data

public interface CompressionStrategy {

public OutputStream compress(OutputStream data) throws IOException;

}

We have two concrete implementations of this interface, one for gzip and one for ZIP, which use the built-in Java classes to write gzip (Example 8-10) and ZIP (Example 8-11) files.

Example 8-10. Using the gzip algorithm to compress data

public class GzipCompressionStrategy implements CompressionStrategy {

@Override

public OutputStream compress(OutputStream data) throws IOException {

return new GZIPOutputStream(data);

}

}

Example 8-11. Using the zip algorithm to compress data

public class ZipCompressionStrategy implements CompressionStrategy {

@Override

public OutputStream compress(OutputStream data) throws IOException {

return new ZipOutputStream(data);

}

}

Now we can implement our Compressor class, which is the context in which we use our strategy. This has a compress method on it that takes input and output files and writes a compressed version of the input file to the output file. It takes the CompressionStrategy as a constructor parameter that its calling code can use to make a runtime choice as to which compression strategy to use—for example, getting user input that would make the decision (see Example 8-12).

Example 8-12. Our compressor is provided with a compression strategy at construction time

public class Compressor {

private final CompressionStrategy strategy;

public Compressor(CompressionStrategy strategy) {

this.strategy = strategy;

}

public void compress(Path inFile, File outFile) throws IOException {

try (OutputStream outStream = new FileOutputStream(outFile)) {

Files.copy(inFile, strategy.compress(outStream));

}

}

}

If we have a traditional implementation of the strategy pattern, then we can write client code that creates a new Compressor with whichever strategy we want (Example 8-13).

Example 8-13. Instantiating the Compressor using concrete strategy classes

Compressor gzipCompressor = new Compressor(new GzipCompressionStrategy());

gzipCompressor.compress(inFile, outFile);

Compressor zipCompressor = new Compressor(new ZipCompressionStrategy());

zipCompressor.compress(inFile, outFile);

As with the command pattern discussed earlier, using either lambda expressions or method references allows us to remove a whole layer of boilerplate code from this pattern. In this case, we can remove each of the concrete strategy implementations and refer to a method that implements the algorithm. Here the algorithms are represented by the constructors of the relevant OutputStream implementation. We can totally dispense with the GzipCompressionStrategy and ZipCompressionStrategy classes when taking this approach. Example 8-14 is what the code would look like if we used method references.

Example 8-14. Instantiating the Compressor using method references

Compressor gzipCompressor = new Compressor(GZIPOutputStream::new);

gzipCompressor.compress(inFile, outFile);

Compressor zipCompressor = new Compressor(ZipOutputStream::new);

zipCompressor.compress(inFile, outFile);

Observer Pattern

The observer pattern is another behavioral pattern that can be improved and simplified through the use of lambda expressions. In the observer pattern, an object, called the subject, maintains a list of other objects, which are its observers. When the state of the subject changes, its observers are notified. It is heavily used in MVC-based GUI toolkits in order to allow view components to be updated when state changes in the model without coupling the two classes together.

Seeing GUI components update is a bit boring, so the subject that we’ll be observing is the moon! Both NASA and some aliens want to keep track of things landing on the moon. NASA wants to make sure its Apollo astronauts have landed safely; the aliens want to invade Earth when NASA is distracted.

Let’s start by defining the API of our observers, which I’ll give the name LandingObserver. This has a single observeLanding method, which will be called when something lands on the moon (Example 8-15).

Example 8-15. An interface for observing organizations that land on the moon

public interface LandingObserver {

public void observeLanding(String name);

}

Our subject class is the Moon, which keeps a list of LandingObserver instances, notifies them of landings, and can add new LandingObserver instances to spy on the Moon object (Example 8-16).

Example 8-16. Our Moon domain class—not as pretty as the real thing

public class Moon {

private final List<LandingObserver> observers = new ArrayList<>();

public void land(String name) {

for (LandingObserver observer : observers) {

observer.observeLanding(name);

}

}

public void startSpying(LandingObserver observer) {

observers.add(observer);

}

}

We have two concrete implementations of the LandingObserver class that represent the aliens’ (Example 8-17) and NASA’s views (Example 8-18) of the landing event. As mentioned earlier, they both have different interpretations of what this situation brings them.

Example 8-17. The aliens can observe people landing on the moon

public class Aliens implements LandingObserver {

@Override

public void observeLanding(String name) {

if (name.contains("Apollo")) {

System.out.println("They're distracted, lets invade earth!");

}

}

}

Example 8-18. NASA can also observe people landing on the moon

public class Nasa implements LandingObserver {

@Override

public void observeLanding(String name) {

if (name.contains("Apollo")) {

System.out.println("We made it!");

}

}

}

In a similar vein to the previous patterns, in our traditional example our client code specifically wires up a layer of boilerplate classes that don’t need to exist if we use lambda expressions (see Examples 8-19 and 8-20).

Example 8-19. Client code building up a Moon using classes and things landing on it

Moon moon = new Moon();

moon.startSpying(new Nasa());

moon.startSpying(new Aliens());

moon.land("An asteroid");

moon.land("Apollo 11");

Example 8-20. Client code building up a Moon using lambdas and things landing on it

Moon moon = new Moon();

moon.startSpying(name -> {

if (name.contains("Apollo"))

System.out.println("We made it!");

});

moon.startSpying(name -> {

if (name.contains("Apollo"))

System.out.println("They're distracted, lets invade earth!");

});

moon.land("An asteroid");

moon.land("Apollo 11");

One thing to think about with both the observer and the strategy patterns is that whether to go down the lambda design route or the class route depends a lot on the complexity of the strategy or observer code that needs to be implemented. In the cases I’ve presented here, the code is simple in nature, just a method call or two, and fits the new language features well. In some situations, though, the observer can be a complex class in and of itself, and in those situations trying to squeeze a lot of code into one method can lead to poor readability.

NOTE

In some respects, trying to squeeze a lot of code into one method leads to poor readability is the golden rule governing how to apply lambda expressions. The only reason I haven’t pushed this so much is that it’s also the golden rule of writing normal methods!

Template Method Pattern

A pretty common situation when developing software is having a common algorithm with a set of differing specifics. We want to require the different implementations to have a common pattern in order to ensure that they’re following the same algorithm and also to make the code easier to understand. Once you understand the overall pattern, you can more easily understand each implementation.

The template method pattern is designed for these kinds of situations. Your overall algorithm design is represented by an abstract class. This has a series of abstract methods that represent customized steps in the algorithm, while any common code can be kept in this class. Each variant of the algorithm is implemented by a concrete class that overrides the abstract methods and provides the relevant implementation.

Let’s think through a scenario in order to make this clearer. As a bank, we’re going to be giving out loans to members of the public, companies, and employees. These categories have a fairly similar loan application process—you check the identity, credit history, and income history. You get this information from different sources and apply different criteria. For example, you might check the identity of a person by looking at an existing bill to her house, but companies have an official registrar such as the SEC in the US or Companies House in the UK.

We can start to model this in code with an abstract LoanApplication class that controls the algorithmic structure and holds common code for reporting the findings of the loan application. There are then concrete subclasses for each of our different categories of applicant:CompanyLoanApplication, PersonalLoanApplication, and EmployeeLoanApplication. Example 8-21 shows what our LoanApplication class would look like.

Example 8-21. The process of applying for a loan using the template method pattern

public abstract class LoanApplication {

public void checkLoanApplication() throws ApplicationDenied {

checkIdentity();

checkCreditHistory();

checkIncomeHistory();

reportFindings();

}

protected abstract void checkIdentity() throws ApplicationDenied;

protected abstract void checkIncomeHistory() throws ApplicationDenied;

protected abstract void checkCreditHistory() throws ApplicationDenied;

private void reportFindings() {

CompanyLoanApplication implements checkIdentity by looking up information in a company registration database, such as Companies House. checkIncomeHistory would involve assessing existing profit and loss statements and balance sheets for the firm.checkCreditHistory would look into existing bad and outstanding debts.

PersonalLoanApplication implements checkIdentity by analyzing the paper statements that the client has been required to provide in order to check that the client’s address exists. checkIncomeHistory involves assessing pay slips and checking whether the person is still employed. checkCreditHistory delegates to an external credit payment provider.

EmployeeLoanApplication is just PersonalLoanApplication with no employment history checking. Conveniently, our bank already checks all its employees’ income histories when hiring them (Example 8-22).

Example 8-22. A special case of an an employee applying for a loan

public class EmployeeLoanApplication extends PersonalLoanApplication {

@Override

protected void checkIncomeHistory() {

// They work for us!

}

}

With lambda expressions and method references, we can think about the template method pattern in a different light and also implement it differently. What the template method pattern is really trying to do is compose a sequence of method calls in a certain order. If we represent the functions as functional interfaces and then use lambda expressions or method references to implement those interfaces, we can gain a huge amount of flexibility over using inheritance to build up our algorithm. Let’s look at how we would implement our LoanApplication algorithm this way, inExample 8-23!

Example 8-23. The special case of an employee applying for a loan

public class LoanApplication {

private final Criteria identity;

private final Criteria creditHistory;

private final Criteria incomeHistory;

public LoanApplication(Criteria identity,

Criteria creditHistory,

Criteria incomeHistory) {

this.identity = identity;

this.creditHistory = creditHistory;

this.incomeHistory = incomeHistory;

}

public void checkLoanApplication() throws ApplicationDenied {

identity.check();

creditHistory.check();

incomeHistory.check();

reportFindings();

}

private void reportFindings() {

As you can see, instead of having a series of abstract methods we’ve got fields called identity, creditHistory, and incomeHistory. Each of these fields implements our Criteria functional interface. The Criteria interface checks a criterion and throws a domain exception if there’s an error in passing the criterion. We could have chosen to return a domain class from the check method in order to denote failure or success, but continuing with an exception follows the broader pattern set out in the original implementation (see Example 8-24).

Example 8-24. A Criteria functional interface that throws an exception if our application fails

public interface Criteria {

public void check() throws ApplicationDenied;

}

The advantage of choosing this approach over the inheritance-based pattern is that instead of tying the implementation of this algorithm into the LoanApplication hierarchy, we can be much more flexible about where to delegate the functionality to. For example, we may decide that ourCompany class should be responsible for all criteria checking. The Company class would then have a series of signatures like Example 8-25.

Example 8-25. The criteria methods on a Company

public void checkIdentity() throws ApplicationDenied;

public void checkProfitAndLoss() throws ApplicationDenied;

public void checkHistoricalDebt() throws ApplicationDenied;

Now all our CompanyLoanApplication class needs to do is pass in method references to those existing methods, as shown in Example 8-26.

Example 8-26. Our CompanyLoanApplication specifies which methods provide each criterion

public class CompanyLoanApplication extends LoanApplication {

public CompanyLoanApplication(Company company) {

super(company::checkIdentity,

company::checkHistoricalDebt,

company::checkProfitAndLoss);

}

}

A motivating reason to delegate the behavior to our Company class is that looking up information about company identity differs between countries. In the UK, Companies House provides a canonical location for registering company information, but in the US this differs from state to state.

Using functional interfaces to implement the criteria doesn’t preclude us from placing implementation within the subclasses, either. We can explicitly use a lambda expression to place implementation within these classes, or use a method reference to the current class.

We also don’t need to enforce inheritance between EmployeeLoanApplication and PersonalLoanApplication to be able to reuse the functionality of EmployeeLoanApplication in PersonalLoanApplication. We can pass in references to the same methods. Whether they do genuinely subclass each other should really be determined by whether loans to employees are a special case of loans to people or a different type of loan. So, using this approach could allow us to model the underlying problem domain more closely.

Lambda-Enabled Domain-Specific Languages

A domain-specific language (DSL) is a programming language focused on a particular part of a software system. They are usually small and frequently less expressive than a general-purpose language, such as Java, for most programming tasks. DSLs are highly specialized: by trading off being good at everything, they get to be good at something.

It’s usual to split up DSLs into two different categories: internal and external. An external DSL is one that is written separately from the source code of your program and then parsed and implemented separately. For example, Cascading Style Sheets (CSS) and regular expressions are commonly used external DSLs.

Internal DSLs are embedded into the programming language that they are written in. If you’ve used mocking libraries, such as JMock or Mockito, or a SQL builder API such as JOOQ or Querydsl, then you’ll be familiar with internal DSLs. In one sense, they’re just regular libraries that have an API designed to be fluent. Despite their simplicity, internal DSLs are valued because they can be a powerful tool for making your code more succinct and easier to read. Ideally, code written in a DSL reads like statements made within the problem domain that it is reflecting.

The introduction of lambda expressions makes it easier to implement DSLs that are fluent and adds another tool to the belt of those wanting to experiment in the DSL arena. We’ll investigate those issues by building a DSL for performing behavior-driven development (BDD) calledLambdaBehave.

BDD is a variant of test-driven development (TDD) that shifts the emphasis onto talking about the behavior of the program rather than simply the tests that it needs to pass. Our design is inspired by the JavaScript BDD framework Jasmine, which has been getting heavy use in frontend circles.Example 8-27 is a simple Jasmine suite that shows you how to create tests using Jasmine.

Example 8-27. Jasmine

describe("A suite is just a function", function() {

it("and so is a spec", function() {

var a = true;

expect(a).toBe(true);

});

});

I appreciate that if you’re not familiar with JavaScript, this may seem confusing. We will be going through the concepts at a gentler pace as we build a Java 8 equivalent next. Just remember that the syntax for a lambda expression in JavaScript is function() { … }.

Let’s take a look at each of the concepts in turn:

§ Each spec describes a single behavior that your program exhibits.

§ An expectation is a way of describing the behavior of the application. You will find expectations in specs.

§ Groups of specs are combined into a suite.

Each of these concepts has an equivalent in a traditional testing framework, such as JUnit. A spec is similar to a test method, an expectation is similar to an assertion, and a suite is similar to a test class.

A DSL in Java

Let’s look at an example of what we’re aiming for with our Java-based BDD framework. Example 8-28 is a specification of some of the behaviors of a Stack.

Example 8-28. Some stories to specify a Stack

public class StackSpec {{

describe("a stack", it -> {

it.should("be empty when created", expect -> {

expect.that(new Stack()).isEmpty();

});

it.should("push new elements onto the top of the stack", expect -> {

Stack<Integer> stack = new Stack<>();

stack.push(1);

expect.that(stack.get(0)).isEqualTo(1);

});

it.should("pop the last element pushed onto the stack", expect -> {

Stack<Integer> stack = new Stack<>();

stack.push(2);

stack.push(1);

expect.that(stack.pop()).isEqualTo(2);

});

});

}}

We start off our suite of specifications using the describe verb. Then we give our suite a name that tells us what it’s describing the behavior of; here, we’ve picked "a stack".

Each of specifications reads as closely to an English sentence as possible. They all start with the prefix it.should, with it referring to the object whose behavior we’re describing. There is then a plain English sentence that tells us what the behavior is that we’re thinking about. We can then describe expectations of the behavior of our object, which all start with the expect.that prefix.

When we check our specifications, we get a simple command-line report that tells us which pass or fail. You’ll notice that “pop the last element pushed onto the stack” expected pop to be equal to 2, not 1, so it has failed:

a stack

should pop the last element pushed onto the stack[expected:![]() but was:

but was:![]() ]

]

should be empty when created

should push new elements onto the top of the stack

How We Got There

So now that you’ve seen the kind of fluency we can get in our DSLs using lambda expressions, let’s have a look at how I implemented the framework under the hood. Hopefully this will give you an idea of how easy it is to implement this kind of framework yourself.

The first thing I saw when I started describing behavior was the describe verb. This is really just a statically imported method. It creates an instance of our Description class for the suite and delegates handling the specification to it. The Description class corresponds to the itparameters in our specification language (see Example 8-29).

Example 8-29. The describe method that starts the definition of a specification

public static void describe(String name, Suite behavior) {

Description description = new Description(name);

behavior.specifySuite(description);

}

Each suite has its code description implemented by the user using a lambda expression. This means that we need a Suite functional interface, shown in Example 8-30, to represent a suite of specifications. You’ll notice it also takes a Description object as an argument, which we passed into it from the describe method.

Example 8-30. Each suite of tests is a lambda expression implementing this interface

public interface Suite {

public void specifySuite(Description description);

}

Not only are suites represented by lambda expressions in our DSL, but so are individual specifications. They also need a functional interface, which I’ll call Specification (Example 8-31). The variable called expect in our code sample is an instance of our Expect class, which I’ll describe later.

Example 8-31. Each specification is a lambda expression implementing this interface

public interface Specification {

public void specifyBehaviour(Expect expect);

}

The Description instance we’ve been passing around comes in handy at this point. We want our users to be able to fluently name their specifications with the it.should clause. This means our Description class needs a should method (see Example 8-32). This is where the real work gets done, as this is the method that actually executes the lambda expression by calling its specifySuite method. Specifications will tell us they have failed by throwing the standard Java AssertionError, and we consider any other Throwable to be an error.

Example 8-32. Our specification lambda expressions get passed into the should method

public void should(String description, Specification specification) {

try {

Expect expect = new Expect();

specification.specifyBehaviour(expect);

Runner.current.recordSuccess(suite, description);

} catch (AssertionError cause) {

Runner.current.recordFailure(suite, description, cause);

} catch (Throwable cause) {

Runner.current.recordError(suite, description, cause);

}

}

When our specifications want to describe an actual expectation, they use the expect.that clause. This means that our Expect class needs to have a method called that for users to call, shown in Example 8-33. This wraps up the object that gets passed in and can then expose fluent methods such as isEqualTo that throw the appropriate assertions if there’s a specification failure.

Example 8-33. The start of the fluent expect chain

public final class Expect {

public BoundExpectation that(Object value) {

return new BoundExpectation(value);

}

// Rest of class omitted

You may have noticed one more detail that I’ve so far ignored and that has nothing to do with lambda expressions. Our StackSpec class didn’t have any methods directly implemented on it, and I wrote the code inside. I’ve been a bit sneaky here and used double braces at the beginning and end of the class definition:

public class StackSpec {{

...

}}

These start an anonymous constructor that lets us execute an arbitrary block of Java code, so it’s really just like writing out the constructor in full, but with a bit less boilerplate. I could have written the following instead:

public class StackSpec {

public StackSpec() {

...

}

}

There’s a lot more work involved in implementing a complete BDD framework, but the purpose of this section is just to show you how to use lambda expressions to create more fluent domain-specific languages. I’ve covered the parts of the DSL that interact with lambda expressions in order to give you a flavor of how to implement this kind of DSL.

Evaluation

One aspect of fluency is the idea that your DSL is IDE-friendly. In other words, you can remember a minimal amount of knowledge and then use code completion to fill in the gaps in memory. This is why we use and pass it the Description and Expect objects. The other alternative would have been to have static imports for methods called it or expect, which is an approach used in some DSLs. If you pass the object into your lambda expression rather than requiring a static import, it makes it easier for a competent IDE user to code complete his way to working code.

The only thing a user needs to remember is the call to describe. The benefits of such an approach might not be obvious purely from reading this text, but I encourage you to test out the framework in a small sample project and see for yourself.

The other thing to notice is that most testing frameworks provide a bunch of annotations and use external magic or reflection. We didn’t need to resort to such tricks. We can directly represent behavior in our DSLs using lambda expressions and treat these as regular Java methods.

Lambda-Enabled SOLID Principles

The SOLID principles are a set of basic principles for designing OO programs. The name itself is a acronym, with each of the five principles named after one of the letters: Single responsibility, Open/closed, Liskov substitution, Interface segregation, and Dependency inversion. The principles act as a set of guidelines to help you implement code that is easy to maintain and extend over time.

Each of the principles corresponds to a set of potential code smells that can exist in your code, and they offer a route out of the problems that they cause. Many books have been written on this topic, and I’m not going to cover the principles in comprehensive detail. I will, however, look at how three of the principles can be applied in the context of lambda expressions. In the Java 8 context, some of the principles can be extended beyond their original limitations.

The Single Responsibility Principle

Every class or method in your program should have only a single reason to change.

An inevitable fact of software development is that requirements change over time. Whether because a new feature needs to be added, your understanding of your problem domain or customer has changed, or you need things to be faster, over time software must evolve.

When the requirements of your software change, the responsibilities of the classes and methods that implement these requirements also change. If you have a class that has more than one responsibility, when a responsibility changes the resulting code changes can affect the other responsibilities that the class possesses. This possibly introduces bugs and also impedes the ability of the code base to evolve.

Let’s consider a simple example program that generates a BalanceSheet. The program needs to tabulate the BalanceSheet from a list of assets and render the BalanceSheet to a PDF report. If the implementer chose to put both the responsibilities of tabulation and rendering into one class, then that class would have two reasons for change. You might wish to change the rendering in order to generate an alternative output, such as HTML. You might also wish to change the level of detail in the BalanceSheet itself. This is a good motivation to decompose this problem at the high level into two classes: one to tabulate the BalanceSheet and one to render it.

The single responsibility principle is stronger than that, though. A class should not just have a single responsibility: it should also encapsulate it. In other words, if I want to change the output format, then I should have to look at only the rendering class and not at the tabulation class.

This is part of the idea of a design exhibiting strong cohesion. A class is cohesive if its methods and fields should be treated together because they are closely related. If you tried to divide up a cohesive class, you would result in accidentally coupling the classes that you have just created.

Now that you’re familiar with the single responsibility principle, the question arises, what does this have to do with lambda expressions? Well Lambda expressions make it a lot easier to implement the single responsibility principle at the method level. Let’s take a look at some code that counts the number of prime numbers up to a certain value (Example 8-34).

Example 8-34. Counting prime numbers with multiple responsibilities in a method

public long countPrimes(int upTo) {

long tally = 0;

for (int i = 1; i < upTo; i++) {

boolean isPrime = true;

for (int j = 2; j < i; j++) {

if (i % j == 0) {

isPrime = false;

}

}

if (isPrime) {

tally++;

}

}

return tally;

}

It’s pretty obvious that we’re really doing two things in Example 8-34:we’re counting numbers with a certain property and we’re checking whether a number is a prime. As shown in Example 8-35, we can easily refactor this to split apart these two responsibilities.

Example 8-35. Counting prime numbers after refactoring out the isPrime check

public long countPrimes(int upTo) {

long tally = 0;

for (int i = 1; i < upTo; i++) {

if (isPrime(i)) {

tally++;

}

}

return tally;

}

private boolean isPrime(int number) {

for (int i = 2; i < number; i++) {

if (number % i == 0) {

return false;

}

}

return true;

}

Unfortunately, we’re still left in a situation where our code has two responsibilities. For the most part, our code here is dealing with looping over numbers. If we follow the single responsibility principle, then iteration should be encapsulated elsewhere. There’s also a good practical reason to improve this code. If we want to count the number of primes for a very large upTo value, then we want to be able to perform this operation in parallel. That’s right—the threading model is a responsibility of the code!

We can refactor our code to use the Java 8 streams library (see Example 8-36), which delegates the responsibility for controlling the loop to the library itself. Here we use the range method to count the numbers between 0 and upTo, filter them to check that they really are prime, and thencount the result.

Example 8-36. Refactoring the prime checking to use streams

public long countPrimes(int upTo) {

return IntStream.range(1, upTo)

.filter(this::isPrime)

.count();

}

private boolean isPrime(int number) {

return IntStream.range(2, number)

.allMatch(x -> (number % x) != 0);

}

If we want to speed up the time it takes to perform this operation at the expense of using more CPU resources, we can use the parallelStream method without changing any of the other code (see Example 8-37).

Example 8-37. The streams-based prime checking running in parallel

public long countPrimes(int upTo) {

return IntStream.range(1, upTo)

.parallel()

.filter(this::isPrime)

.count();

}

private boolean isPrime(int number) {

return IntStream.range(2, number)

.allMatch(x -> (number % x) != 0);

}

So, we can use higher-order functions in order to help us easily implement the single responsibility principle.

The Open/Closed Principle

Software entities should be open for extension, but closed for modification.

— Bertrand Meyer

The overarching goal of the open/closed principle is similar to that of the single responsibility principle: to make your software less brittle to change. Again, the problem is that a single feature request or change to your software can ripple through the code base in a way that is likely to introduce new bugs. The open/closed principle is an effort to avoid that problem by ensuring that existing classes can be extended without their internal implementation being modified.

When you first hear about the open/closed principle, it sounds like a bit of a pipe dream. How can you extend the functionality of a class without having to change its implementation? The actual answer is that you rely on an abstraction and can plug in new functionality that fits into this abstraction. Let’s think through a concrete example.

We’re writing a software program that measures information about system performance and graphs the results of these measurements. For example, we might have a graph that plots how much time the computer spends in user space, kernel space, and performing I/O. I’ll call the class that has the responsibility for displaying these metrics MetricDataGraph.

One way of designing the MetricDataGraph class would be to have each of the new metric points pushed into it from the agent that gathers the data. So, its public API would look something like Example 8-38.

Example 8-38. The MetricDataGraph public API

class MetricDataGraph {

public void updateUserTime(int value);

public void updateSystemTime(int value);

public void updateIoTime(int value);

}

But this would mean that every time we wanted to add in a new set of time points to the plot, we would have to modify the MetricDataGraph class. We can resolve this issue by introducing an abstraction, which I’ll call a TimeSeries, that represents a series of points in time. Now ourMetricDataGraph API can be simplified to not depend upon the different types of metric that it needs to display, as shown in Example 8-39.

Example 8-39. Simplified MetricDataGraph API

class MetricDataGraph {

public void addTimeSeries(TimeSeries values);

}

Each set of metric data can then implement the TimeSeries interface and be plugged in. For example, we might have concrete classes called UserTimeSeries, SystemTimeSeries, and IoTimeSeries. If we wanted to add, say, the amount of CPU time that gets stolen from a machine if it’s virtualized, then we would add a new implementation of TimeSeries called StealTimeSeries. MetricDataGraph has been extended but hasn’t been modified.

Higher-order functions also exhibit the same property of being open for extension, despite being closed for modification. A good example of this is the ThreadLocal class that we encountered earlier. The ThreadLocal class provides a variable that is special in the sense that each thread has a single copy for it to interact with. Its static withInitial method is a higher-order function that takes a lambda expression that represents a factory for producing an initial value.

This implements the open/closed principle because we can get new behavior out of ThreadLocal without modifying it. We pass in a different factory method to withInitial and get an instance of ThreadLocal with different behavior. For example, we can use ThreadLocal to produce a DateFormatter that is thread-safe with the code in Example 8-40.

Example 8-40. A ThreadLocal date formatter

// One implementation

ThreadLocal<DateFormat> localFormatter

= ThreadLocal.withInitial(() -> new SimpleDateFormat());

// Usage

DateFormat formatter = localFormatter.get();

We can also generate completely different behavior by passing in a different lambda expression. For example, in Example 8-41 we’re creating a unique identifier for each Java thread that is sequential.

Example 8-41. A ThreadLocal identifier

// Or...

AtomicInteger threadId = new AtomicInteger();

ThreadLocal<Integer> localId

= ThreadLocal.withInitial(() -> threadId.getAndIncrement());

// Usage

int idForThisThread = localId.get();

Another interpretation of the open/closed principle that doesn’t follow in the traditional vein is the idea that immutable objects implement the open/closed principle. An immutable object is one that can’t be modified after it is created.

The term “immutability” can have two potential interpretations: observable immutability or implementation immutability. Observable immutability means that from the perspective of any other object, a class is immutable; implementation immutability means that the object never mutates. Implementation immutability implies observable immutability, but the inverse isn’t necessarily true.

A good example of a class that proclaims its immutability but actually is only observably immutable is java.lang.String, as it caches the hash code that it computes the first time its hashCode method is called. This is entirely safe from the perspective of other classes because there’s no way for them to observe the difference between it being computed in the constructor every time or cached.

I mention immutable objects in the context of a book on lambda expressions because they are a fairly familiar concept within functional programming, which is the same area that lambda expressions have come from. They naturally fit into the style of programming that I’m talking about in this book.

Immutable objects implement the open/closed principle in the sense that because their internal state can’t be modified, it’s safe to add new methods to them. The new methods can’t alter the internal state of the object, so they are closed for modification, but they are adding behavior, so they are open to extension. Of course, you still need to be careful in order to avoid modifying state elsewhere in your program.

Immutable objects are also of particular interest because they are inherently thread-safe. There is no internal state to mutate, so they can be shared between different threads.

If we reflect on these different approaches, it’s pretty clear that we’ve diverged quite a bit from the traditional open/closed principle. In fact, when Bertrand Meyer first introduced the principle, he defined it so that the class itself couldn’t ever be altered after being completed. Within a modernAgile developer environment it’s pretty clear that the idea of a class being complete is fairly outmoded. Business requirements and usage of the application may dictate that a class be used for something that it wasn’t intended to be used for. That’s not a reason to ignore the open/closed principle though, just a good example of how these principles should be taken as guidelines and heuristics rather than followed religiously or to the extreme.

A final point that I think is worth reflecting on is that in the context of Java 8, interpreting the open/closed principle as advocating an abstraction that we can plug multiple classes into or advocating higher-order functions amounts to the same thing. Because our abstraction needs to be represented by either an interface or an abstract class upon which methods are called, this approach to the open/closed principle is really just a usage of polymorphism.

In Java 8, any lambda expression that gets passed into a higher-order function is represented by a functional interface. The higher-order function calls its single method, which leads to different behavior depending upon which lambda expression gets passed in. Again, under the hood we’re using polymorphism in order to implement the open/closed principle.

The Dependency Inversion Principle

Abstractions should not depend on details; details should depend on abstractions.

One of the ways in which we can make rigid and fragile programs that are resistant to change is by coupling high-level business logic and low-level code that is designed to glue modules together. This is because these are two different concerns that may change over time.

The goal of the dependency inversion principle is to allow programmers to write high-level business logic that is independent of low-level glue code. This allows us to reuse the high-level code in a way that is abstract of the details upon which it depends. This modularity and reuse goes both ways: we can substitute in different details in order to reuse the high-level code, and we can reuse the implementation details by layering alternative business logic on top.

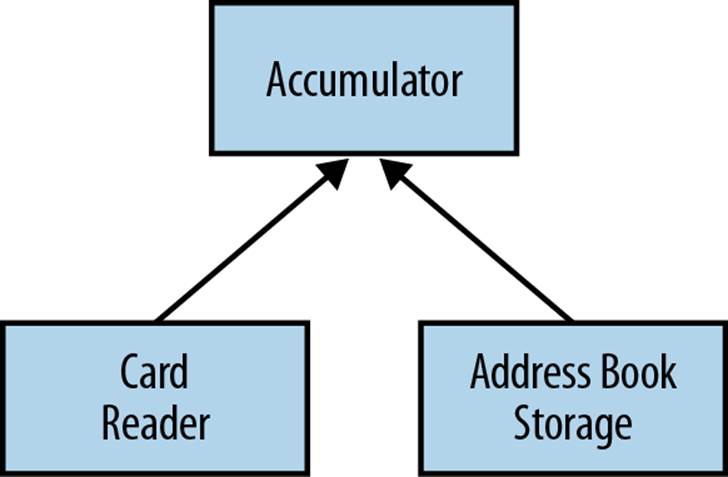

Let’s look at a concrete example of how the dependency inversion principle is traditionally used by thinking through the high-level decomposition involved in implementing an application that builds up an address book automatically. Our application takes in a sequence of electronic business cards as input and accumulates our address book in some storage mechanism.

It’s fairly obvious that we can separate this code into three basic modules:

§ The business card reader that understands an electronic business card format

§ The address book storage that stores data into a text file

§ The accumulation module that takes useful information from the business cards and puts it into the address book

We can visualize the relationship between these modules as shown in Figure 8-3.

Figure 8-3. Dependencies

In this system, while reuse of the accumulation model is more complex, the business card reader and the address book storage do not depend on any other components. We can therefore easily reuse them in another system. We can also change them; for example, we might want to use a different reader, such as reading from people’s Twitter profiles, or we might want to store our address book in something other than a text file, such as a database.

In order to give ourselves the flexibility to change these components within our system, we need to ensure that the implementation of our accumulation module doesn’t depend upon the specific details of either the business card reader or the address book storage. So, we introduce an abstraction for reading information and an abstraction for writing information. The implementation of our accumulation module depends upon these abstractions. We can pass in the specific details of these implementations at runtime. This is the dependency inversion principle at work.

In the context of lambda expressions, many of the higher-order functions that we’ve encountered enable a dependency inversion. A function such as map allows us to reuse code for the general concept of transforming a stream of values between different specific transformations. The mapfunction doesn’t depend upon the details of any of these specific transformations, but upon an abstraction. In this case, the abstraction is the functional interface Function.

A more complex example of dependency inversion is resource management. Obviously, there are lots of resources that can be managed, such as database connections, thread pools, files, and network connections. I’ll use files as an example because they are a relatively simple resource, but the principle can easily be applied to more complex resources within your application.

Let’s look at some code that extracts headings from a hypothetical markup language where each heading is designated by being suffixed with a colon (:). Our method is going to extract the headings from a file by reading the file, looking at each of the lines in turn, filtering out the headings, and then closing the file. We shall also wrap any Exception related to the file I/O into a friendly domain exception called a HeadingLookupException. The code looks like Example 8-42.

Example 8-42. Parsing the headings out of a file

public List<String> findHeadings(Reader input) {

try (BufferedReader reader = new BufferedReader(input)) {

return reader.lines()

.filter(line -> line.endsWith(":"))

.map(line -> line.substring(0, line.length() - 1))

.collect(toList());

} catch (IOException e) {

throw new HeadingLookupException(e);

}

}

Unfortunately, our heading-finding code is coupled with the resource-management and file-handling code. What we really want to do is write some code that finds the headings and delegates the details of a file to another method. We can use a Stream<String> as the abstraction we want to depend upon rather than a file. A Stream is much safer and less open to abuse. We also want to be able to a pass in a function that creates our domain exception if there’s a problem with the file. This approach, shown in Example 8-43, allows us to segregate the domain-level error handling from the resource management–level error handling.

Example 8-43. The domain logic with file handling split out

public List<String> findHeadings(Reader input) {

return withLinesOf(input,

lines -> lines.filter(line -> line.endsWith(":"))

.map(line -> line.substring(0, line.length()-1))

.collect(toList()),

HeadingLookupException::new);

}

I expect that you’re now wondering what that withLinesOf method looks like! It’s shown in Example 8-44.

Example 8-44. The definition of withLinesOf

private <T> T withLinesOf(Reader input,

Function<Stream<String>, T> handler,

Function<IOException, RuntimeException> error) {

try (BufferedReader reader = new BufferedReader(input)) {

return handler.apply(reader.lines());

} catch (IOException e) {

throw error.apply(e);

}

}

withLinesOf takes in a reader that handles the underlying file I/O. This is wrapped up in BufferedReader, which lets us read the file line by line. The handler function represents the body of whatever code we want to use with this function. It takes the Stream of the file’s lines as its argument. We also take another handler called error that gets called when there’s an exception in the I/O code. This constructs whatever domain exception we want. This exception then gets thrown in the event of a problem.

To summarize, higher-order functions provide an inversion of control, which is a form of dependency inversion. We can easily use them with lambda expressions. The other thing to note with the dependency inversion principle is that the abstraction that we depend upon doesn’t have to be aninterface. Here we’ve relied upon the existing Stream as an abstraction over raw reader and file handling. This approach also fits into the way that resource management is performed in functional languages—usually a higher-order function manages the resource and takes a callback function that is applied to an open resource, which is closed afterward. In fact, if lambda expressions had been available at the time, it’s arguable that the try-with-resources feature of Java 7 could have been implemented with a single library function.

Further Reading

A lot of the discussion in this chapter has delved into broader design issues, looking at the whole of your program rather than just local issues related to a single method. This is an area that we’ve just touched the surface of due to the lambda expressions focus of this book. There are a number of other books covering related topic areas that are worth investigating if you’re interested in more detail.

The SOLID principles have long been emphasized by “Uncle” Bob Martin, who has both written and presented extensively on the topic. If you want to osmose some of his knowledge for free, a series of articles on each of the principles is available on the Object Mentor website, under the topic “Design Patterns.”

If you are interested in a more comprehensive understanding of domain-specific languages, both internal and external, Domain-Specific Languages by Martin Fowler with Rebecca Parsons (Addison-Wesley) is recommended reading.

Key Points

§ Lambda expressions can be used to make many existing design patterns simpler and more readable, especially the command pattern.

§ There is more flexibility to the kind of domain-specific languages you can create with Java 8.

§ New opportunities open up for applying the SOLID principles in Java 8.