Web Development with Node and Express (2014)

Chapter 6. The Request and Response Objects

When you’re building a web server with Express, most of what you’ll be doing starts with a request object and ends with a response object. These two objects originate in Node and are extended by Express. Before we delve into what these objects offer us, let’s establish a little background on how a client (a browser, usually) requests a page from a server, and how that page is returned.

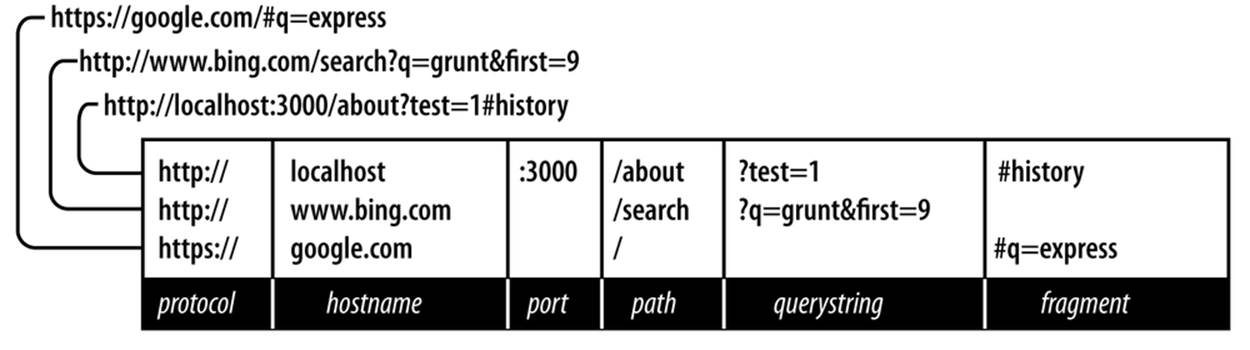

The Parts of a URL

Protocol

The protocol determines how the request will be transmitted. We will be dealing exclusively with http and https. Other common protocols include file and ftp.

Host

The host identifies the server. Servers on your computer (localhost) or a local network may simply be one word, or it may be a numeric IP address. On the Internet, the host will end in a top-level domain (TLD) like .com or .net. Additionally, there may be subdomains, which prefix the hostname. www is a very common subdomain, though it can be anything. Subdomains are optional.

Port

Each server has a collection of numbered ports. Some port numbers are “special,” like 80 and 443. If you omit the port, port 80 is assumed for HTTP and 443 for HTTPS. In general, if you aren’t using port 80 or 443, you should use a port number greater than 1023.[6] It’s very common to use easy-to-remember port numbers like 3000, 8080, and 8088.

Path

The path is generally the first part of the URL that your app cares about (it is possible to make decisions based on protocol, host, and port, but it’s not good practice). The path should be used to uniquely identify pages or other resources in your app.

Querystring

The querystring is an optional collection of name/value pairs. The querystring starts with a question mark (?), and name/value pairs are separated by ampersands (&). Both names and values should be URL encoded. JavaScript provides a built-in function to do that:encodeURIComponent. For example, spaces will be replaced with plus signs (+). Other special characters will be replaced with numeric character references.

Fragment

The fragment (or hash) is not passed to the server at all: it is strictly for use by the browser. It is becoming increasingly common for single-page applications or AJAX-heavy applications to use the fragment to control the application. Originally, the fragment’s sole purpose was to cause the browser to display a specific part of the document, marked by an anchor tag (<a id="chapter06">).

HTTP Request Methods

The HTTP protocol defines a collection of request methods (often referred to as HTTP verbs) that a client uses to communicate with a server. Far and away, the most common methods are GET and POST.

When you type a URL into a browser (or click a link), the browser issues an HTTP GET request to the server. The important information passed to the server is the URL path and querystring. The combination of method, path, and querystring is what your app uses to determine how to respond.

For a website, most of your pages will respond to GET requests. POST requests are usually reserved for sending information back to the server (form processing, for example). It’s quite common for POST requests to respond with the same HTML as the corresponding GET request after the server has processed any information included in the request (like a form). Browsers will exclusively use the GET and POST methods when communicating with your server (if they’re not using AJAX).

Web services, on the other hand, often get more creative with the HTTP methods used. For example, there’s an HTTP method called DELETE that is useful for, well, an API call that deletes things.

With Node and Express, you are fully in charge of what methods you respond to (though some of the more esoteric ones are not very well supported). In Express, you’ll usually be writing handlers for specific methods.

Request Headers

The URL isn’t the only thing that’s passed to the server when you navigate to a page. Your browser is sending a lot of “invisible” information every time you visit a website. I’m not talking about spooky personal information (though if your browser is infected by malware, that can happen). The browser will tell the server what language it prefers to receive the page in (for example, if you download Chrome in Spain, it will request the Spanish version of pages you visit, if they exist). It will also send information about the “user agent” (the browser, operating system, and hardware) and other bits of information. All this information is sent as a request header, which is made available to you through the request object’s headers property. If you’re curious to see the information your browser is sending, you can create a very simple Express route to display that information:

app.get('/headers', function(req,res){

res.set('Content-Type','text/plain');

var s = '';

for(var name in req.headers) s += name + ': ' + req.headers[name] + '\n';

res.send(s);

});

Response Headers

Just as your browser sends hidden information to the server in the form of request headers, when the server responds, it also sends information back that is not necessarily rendered or displayed by the browser. The information typically included in response headers is metadata and server information. We’ve already seen the Content-Type header, which tells the browser what kind of content is being transmitted (HTML, an image, CSS, JavaScript, etc.). Note that the browser will respect the Content-Type header regardless of what the URL path is. So you could serve HTML from a path of /image.jpg or an image from a path of /text.html. (There’s no legitimate reason to do this; it’s just important to understand that paths are abstract, and the browser uses Content-Type to determine how to render content.) In addition to Content-Type, headers can indicate whether the response is compressed and what kind of encoding it’s using. Response headers can also contain hints for the browser about how long it can cache the resource. This is an important consideration for optimizing your website, and we’ll be discussing that in detail inChapter 16. It is also common for response headers to contain some information about the server, indicating what type of server it is, and sometimes even details about the operating system. The downside about returning server information is that it gives hackers a starting point to compromise your site. Extremely security-conscious servers often omit this information, or even provide false information. Disabling Express’s default X-Powered-By header is easy:

app.disable('x-powered-by');

If you want to see the response headers, they can be found in your browser’s developer tools. To see the response headers in Chrome, for example:

1. Open the JavaScript console.

2. Click the Network tab.

3. Reload the page.

4. Pick the HTML from the list of requests (it will be the first one).

5. Click the Headers tab; you will see all response headers.

Internet Media Types

The Content-Type header is critically important: without it, the client would have to painfully guess how to render the content. The format of the Content-Type header is an Internet media type, which consists of a type, subtype, and optional parameters. For example, text/html; charset=UTF-8 specifies a type of “text,” a subtype of “html,” and a character encoding of UTF-8. The Internet Assigned Numbers Authority maintains an official list of Internet media types. Often, you will hear “content type,” “Internet media type,” and “MIME type” used interchangeably. MIME (Multipurpose Internet Mail Extensions) was a precursor of Internet media types and, for the most part, is equivalent.

Request Body

In addition to the request headers, a request can have a body (just like the body of a response is the actual content that’s being returned). Normal GET requests don’t have bodies, but POST requests usually do. The most common media type for POST bodies is application/x-www-form-urlencoded, which is simply encoded name/value pairs separated by ampersands (essentially the same format as a querystring). If the POST needs to support file uploads, the media type is multipart/form-data, which is a more complicated format. Lastly, AJAX requests can useapplication/json for the body.

Parameters

The word “parameters” can mean a lot of things, and is often a source of confusion. For any request, parameters can come from the querystring, the session (requiring cookies; see Chapter 9), the request body, or the named routing parameters (which we’ll learn more about in Chapter 14). In Node applications, the param method of the request object munges all of these parameters together. For this reason, I encourage you to avoid it. This commonly causes problems when a parameter is set to one thing in the querystring and another one in the POST body or the session: which value wins? It can produce maddening bugs. PHP is largely to blame for this confusion: in an effort to be “convenient,” it munged all of these parameters into a variable called $_REQUEST, and for some reason, people have thought it was a good idea ever since. We will learn about dedicated properties that hold the various types of parameters, and I feel that that is a much less confusing approach.

The Request Object

The request object (which is normally passed to a callback, meaning you can name it whatever you want: it is common to name it req or request) starts its life as an instance of http.IncomingMessage, a core Node object. Express adds additional functionality. Let’s look at the most useful properties and methods of the request object (all of these methods are added by Express, except for req.headers and req.url, which originate in Node):

req.params

An array containing the named route parameters. We’ll learn more about this in Chapter 14.

req.param(name)

Returns the named route parameter, or GET or POST parameters. I recommend avoiding this method.

req.query

An object containing querystring parameters (sometimes called GET parameters) as name/value pairs.

req.body

An object containing POST parameters. It is so named because POST parameters are passed in the body of the REQUEST, not in the URL like querystring parameters. To make req.body available, you’ll need middleware that can parse the body content type, which we will learn about inChapter 10.

req.route

Information about the currently matched route. Primarily useful for route debugging.

req.cookies/req.signedCookies

Objects containing containing cookie values passed from the client. See Chapter 9.

req.headers

The request headers received from the client.

req.accepts([types])

A convenience method to determine whether the client accepts a given type or types (optional types can be a single MIME type, such as application/json, a comma-delimited list, or an array). This method is of primary interest to those writing public APIs; it is assumed that browsers will always accept HTML by default.

req.ip

The IP address of the client.

req.path

The request path (without protocol, host, port, or querystring).

req.host

A convenience method that returns the hostname reported by the client. This information can be spoofed and should not be used for security purposes.

req.xhr

A convenience property that returns true if the request originated from an AJAX call.

req.protocol

The protocol used in making this request (for our purposes, it will either be http or https).

req.secure

A convenience property that returns true if the connection is secure. Equivalent to req.protocol==='https'.

req.url/req.originalUrl

A bit of a misnomer, these properties return the path and querystring (they do not include protocol, host, or port). req.url can be rewritten for internal routing purposes, but req.originalUrl is designed to remain the original request and querystring.

req.acceptedLanguages

A convenience method that returns an array of the (human) languages the client prefers, in order. This information is parsed from the request header.

The Response Object

The response object (which is normally passed to a callback, meaning you can name it whatever you want: it is common to name it res, resp, or response) starts its life as an instance of http.ServerResponse, a core Node object. Express adds additional functionality. Let’s look at the most useful properties and methods of the response object (all of these are added by Express):

res.status(code)

Sets the HTTP status code. Express defaults to 200 (OK), so you will have to use this method to return a status of 404 (Not Found) or 500 (Server Error), or any other status code you wish to use. For redirects (status codes 301, 302, 303, and 307), there is a method redirect, which is preferable.

res.set(name, value)

Sets a response header. This is not something you will normally be doing manually.

res.cookie(name, value, [options]), res.clearCookie(name, [options])

Sets or clears cookies that will be stored on the client. This requires some middleware support; see Chapter 9.

res.redirect([status], url)

Redirects the browser. The default redirect code is 302 (Found). In general, you should minimize redirection unless you are permanently moving a page, in which case you should use the code 301 (Moved Permanently).

res.send(body), res.send(status, body)

Sends a response to the client, with an optional status code. Express defaults to a content type of text/html, so if you want to change it to text/plain (for example), you’ll have to call res.set('Content-Type', 'text/plain\') before calling res.send. If body is an object or an array, the response is sent as JSON instead (with the content type being set appropriately), though if you want to send JSON, I recommend doing so explicitly by calling res.json instead.

res.json(json), res.json(status, json)

Sends JSON to the client with an optional status code.

res.jsonp(json), res.jsonp(status, json)

Sends JSONP to the client with an optional status code.

res.type(type)

A convenience method to set the Content-Type header. Essentially equivalent to res.set('Content-Type', type), except that it will also attempt to map file extensions to an Internet media type if you provide a string without a slash in it. For example, res.type('txt') will result in a Content-Type of text/plain. There are areas where this functionality could be useful (for example, automatically serving disparate multimedia files), but in general, you should avoid it in favor of explicitly setting the correct Internet media type.

res.format(object)

This method allows you to send different content depending on the Accept request header. This is of primary use in APIs, and we will discuss this more in Chapter 15. Here’s a very simple example: res.format({'text/plain': 'hi there', 'text/html': '<b>hi there</b>'}).

res.attachment([filename]), res.download(path, [filename], [callback])

Both of these methods set a response header called Content-Disposition to attachment; this will prompt the browser to download the content instead of displaying it in a browser. You may specify filename as a hint to the browser. With res.download, you can specify the file to download, whereas res.attachment just sets the header; you still have to send content to the client.

res.sendFile(path, [options], [callback])

This method will read a file specified by path and send its contents to the client. There should be little need for this method; it’s easier to use the static middleware, and put files you want available to the client in the public directory. However, if you want to have a different resource served from the same URL depending on some condition, this method could come in handy.

res.links(links)

Sets the Links response header. This is a specialized header that has little use in most applications.

res.locals, res.render(view, [locals], callback)

res.locals is an object containing default context for rendering views. res.render will render a view using the configured templating engine (the locals parameter to res.render shouldn’t be confused with res.locals: it will override the context in res.locals, but context not overridden will still be available). Note that res.render will default to a response code of 200; use res.status to specify a different response code. Rendering views will be covered in depth in Chapter 7.

Getting More Information

Because of JavaScript’s prototypal inheritance, knowing exactly what you’re dealing with can be challenging sometimes. Node provides you with objects that Express extends, and packages that you add may also extend those. Figuring out exactly what’s available to you can be challenging sometimes. In general, I would recommend working backward: if you’re looking for some functionality, first check the Express API documentation. The Express API is pretty complete, and chances are, you’ll find what you’re looking for there.

If you need information that isn’t documented, sometimes you have to dive into the Express source. I encourage you to do this! You’ll probably find that it’s a lot less intimidating than you might think. Here’s a quick roadmap to where you’ll find things in the Express source:

lib/application.js

The main Express interface. If you want to understand how middleware is linked in, or how views are rendered, this is the place to look.

lib/express.js

This is a relatively short shell that extends Connect with the functionality in lib/application.js, and returns a function that can be used with http.createServer to actually run an Express app.

lib/request.js

Extends Node’s http.IncomingMessage object to provide a robust request object. For information about all the request object properties and methods, this is where to look.

lib/response.js

Extends Node’s http.ServerResponse object to provide the response object. For information about response object properties and methods, this is where to look.

lib/router/route.js

Provides basic routing support. While routing is central to your app, this file is less than 200 lines long; you’ll find that it’s quite simple and elegant.

As you dig into the Express source code, you’ll probably want to refer to the Node documentation, especially the section on the HTTP module.

Boiling It Down

This chapter has tried to provide an overview of the request and response objects, which are the meat and potatoes of an Express application. However, the chances are that you will be using a small subset of this functionality most of the time. So let’s break it down by functionality you’ll be using most frequently.

Rendering Content

When you’re rendering content, you’ll be using res.render most often, which renders views within layouts, providing maximum value. Occasionally, you may wish to write a quick test page, so you might use res.send if you just want a test page. You may use req.query to get querystring values, req.session to get session values, or req.cookie/req.signedCookies to get cookies. Examples 6-1 to 6-8 demonstrate common content rendering tasks:

Example 6-1. Basic usage

// basic usage

app.get('/about', function(req, res){

res.render('about');

});

Example 6-2. Response codes other than 200

app.get('/error', function(req, res){

res.status(500);

res.render('error');

});

// or on one line...

app.get('/error', function(req, res){

res.status(500).render('error');

});

Example 6-3. Passing a context to a view, including querystring, cookie, and session values

app.get('/greeting', function(req, res){

res.render('about', {

message: 'welcome',

style: req.query.style,

userid: req.cookie.userid,

username: req.session.username,

});

});

Example 6-4. Rendering a view without a layout

// the following layout doesn't have a layout file, so views/no-layout.handlebars

// must include all necessary HTML

app.get('/no-layout', function(req, res){

res.render('no-layout', { layout: null });

});

Example 6-5. Rendering a view with a custom layout

// the layout file views/layouts/custom.handlebars will be used

app.get('/custom-layout', function(req, res){

res.render('custom-layout', { layout: 'custom' });

});

Example 6-6. Rendering plaintext output

app.get('/test', function(req, res){

res.type('text/plain');

res.send('this is a test');

});

Example 6-7. Adding an error handler

// this should appear AFTER all of your routes

// note that even if you don't need the "next"

// function, it must be included for Express

// to recognize this as an error handler

app.use(function(err, req, res, next){

console.error(err.stack);

res.status(500).render('error');

});

Example 6-8. Adding a 404 handler

// this should appear AFTER all of your routes

app.use(function(req, res){

res.status(404).render('not-found');

});

Processing Forms

When you’re processing forms, the information from the forms will usually be in req.body (or occasionally in req.query). You may use req.xhr to determine if the request was an AJAX request or a browser request (this will be covered in depth in Chapter 8). See Examples 6-9 and 6-10.

Example 6-9. Basic form processing

// body-parser middleware must be linked in

app.post('/process-contact', function(req, res){

console.log('Received contact from ' + req.body.name +

' <' + req.body.email + '>');

// save to database....

res.redirect(303, '/thank-you');

});

Example 6-10. More robust form processing

// body-parser middleware must be linked in

app.post('/process-contact', function(req, res){

console.log('Received contact from ' + req.body.name +

' <' + req.body.email + '>');

try {

// save to database....

return res.xhr ?

res.render({ success: true }) :

res.redirect(303, '/thank-you');

} catch(ex) {

return res.xhr ?

res.json({ error: 'Database error.' }) :

res.redirect(303, '/database-error');

}

});

Providing an API

When you’re providing an API, much like processing forms, the parameters will usually be in req.query, though you can also use req.body. What’s different about APIs is that you’ll usually be returning JSON, XML, or even plaintext, instead of HTML, and you’ll often be using less common HTTP methods like PUT, POST, and DELETE. Providing an API will be covered in Chapter 15. Examples 6-11 and 6-12 use the following “products” array (which would normally be retrieved from a database):

var tours = [

{ id: 0, name: 'Hood River', price: 99.99 },

{ id: 1, name: 'Oregon Coast', price: 149.95 },

];

NOTE

The term “endpoint” is often used to describe a single function in an API.

Example 6-11. Simple GET endpoint returning only JSON

app.get('/api/tours'), function(req, res){

res.json(tours);

});

Example 6-12 uses the res.format method in Express to respond according to the preferences of the client.

Example 6-12. GET endpoint that returns JSON, XML, or text

app.get('/api/tours', function(req, res){

var toursXml = '<?xml version="1.0"?><tours>' +

products.map(function(p){

return '<tour price="' + p.price +

'" id="' + p.id + '">' + p.name + '</tour>';

}).join('') + '</tours>'';

var toursText = tours.map(function(p){

return p.id + ': ' + p.name + ' (' + p.price + ')';

}).join('\n');

res.format({

'application/json': function(){

res.json(tours);

},

'application/xml': function(){

res.type('application/xml');

res.send(toursXml);

},

'text/xml': function(){

res.type('text/xml');

res.send(toursXml);

}

'text/plain': function(){

res.type('text/plain');

res.send(toursXml);

}

});

});

In Example 6-13, the PUT endpoint updates a product and returns JSON. Parameters are passed in the querystring (the ":id" in the route string tells Express to add an id property to req.params).

Example 6-13. PUT endpoint for updating

// API that updates a tour and returns JSON; params are passed using querystring

app.put('/api/tour/:id', function(req, res){

var p = tours.some(function(p){ return p.id == req.params.id });

if( p ) {

if( req.query.name ) p.name = req.query.name;

if( req.query.price ) p.price = req.query.price;

res.json({success: true});

} else {

res.json({error: 'No such tour exists.'});

}

});

Finally, Example 6-14 shows a DEL endpoint.

Example 6-14. DEL endpoint for deleting

// API that deletes a product

api.del('/api/tour/:id', function(req, res){

var i;

for( var i=tours.length-1; i>=0; i-- )

if( tours[i].id == req.params.id ) break;

if( i>=0 ) {

tours.splice(i, 1);

res.json({success: true});

} else {

res.json({error: 'No such tour exists.'});

}

});

[6] Ports 0-1023 are “well-known ports.”