Web Development with Node and Express (2014)

Chapter 7. Templating with Handlebars

If you aren’t using templating—or if you don’t know what templating is—it’s the single most important thing you’re going to get out of this book. If you’re coming from a PHP background, you may wonder what the fuss is all about: PHP is one of the first languages that could really be called a templating language. Almost all major languages that have been adapted for the Web have included some kind of templating support. What is different today is that the “templating engine” is being decoupled from the language. Case in point is Mustache: an extremely popular language-agnostic templating engine.

So what is templating? Let’s start with what templating isn’t by considering the most obvious and straightforward way to generate one language from another (specifically, we’ll generate some HTML with JavaScript):

document.write('<h1>Please Don\'t Do This</h1>');

document.write('<p><span class="code">document.write</span> is naughty,\n');

document.write('and should be avoided at all costs.</p>');

document.write('<p>Today\'s date is ' + new Date() + '.</p>');

Perhaps the only reason this seems “obvious” is that it’s the way programming has always been taught:

10 PRINT "Hello world!"

In imperative languages, we’re used to saying, “Do this, then do that, then do something else.” For some things, this approach works fine. If you have 500 lines of JavaScript to perform a complicated calculation that results in a single number, and every step is dependent on the previous step, there’s no harm in it. What if it’s the other way around, though? You have 500 lines of HTML and 3 lines of JavaScript. Does it make sense to write document.write 500 times? Not at all.

Really, the problem boils down to this: switching context is problematic. If you’re writing lots of JavaScript, it’s inconvenient and confusing to be mixing in HTML. The other way isn’t so bad: we’re quite used to writing JavaScript in <script> blocks, but hopefully you see the difference: there’s still a context switch, and you’re either writing HTML or you’re in a <script> block writing JavaScript. Having JavaScript emit HTML is fraught with problems:

§ You have to constantly worry about what characters need to be escaped, and how to do that.

§ Using JavaScript to generate HTML that itself includes JavaScript quickly leads to madness.

§ You usually lose the nice syntax highlighting and other handy language-specific features your editor has.

§ It can be much harder to spot malformed HTML.

§ It’s hard to visually parse.

§ It can make it harder for other people to understand your code.

Templating solves the problem by allowing you to write in the target language, while at the same time providing the ability to insert dynamic data. Consider the previous example rewritten as a Mustache template:

<h1>Much Better</h1>

<p>No <span class="code">document.write</span> here!</p>

<p>Today's date is {{today}}.</p>

Now all we have to do is provide a value for {{today}}, and that’s at the heart of templating languages.

There Are No Absolute Rules Except This One[7]

I’m not suggesting that you should never write HTML in JavaScript: only that you should avoid it whenever possible. In particular, it’s slightly more palatable in frontend code, thanks to libraries like jQuery. For example, this would pass with little comment from me:

$('#error').html('Something <b>very bad</b> happened!');

However, if that eventually mutated into this:

$('#error').html('<div class="error"><h3>Error</h3>' +

'<p>Something <b><a href="/error-detail/' + errorNumber

+'">very bad</a></b> ' +

'happened. <a href="/try-again">Try again<a>, or ' +

'<a href="/contact">contact support</a>.</p></div>');

I might suggest it’s time to employ a template. The point is, I suggest you use your best judgment when deciding where to draw the line between HTML in strings and using templates. I would err on the side of templates, however, and avoid generating HTML with JavaScript except for the simplest cases.

Choosing a Template Engine

In the Node world, you have many templating engines to choose from, so how to pick? It’s a complicated question, and very much depends on your needs. Here are some criteria to consider, though:

Performance

Clearly, you want your templating engine to be as fast as possible. It’s not something you want slowing down your website.

Client, server, or both?

Most, but not all, templating engines are available on both the server and client sides. If you need to use templates in both realms (and you will), I recommend you pick something that is equally capable in either capacity.

Abstraction

Do you want something familiar (like normal HTML with curly brackets thrown in, for example), or do you secretly hate HTML and would love something that saves you from all those angle brackets? Templating (especially server-side templating) gives you some choices here.

These are just some of the more prominent criteria in selecting a templating language. If you want a more detailed discussion on this topic, I highly recommend Veena Basavaraj’s blog post about her selection criteria when choosing a templating language for LinkedIn.

LinkedIn’s choice was Dust, but Handlebars was also in the winner’s circle, which is my preferred template engine, and the one we’ll be using in this book.

Express allows you to use any templating engine you wish, so if Handlebars is not to your liking, you’ll find it’s very easy to switch it out. If you want to explore your options, you can use this fun and useful Template-Engine-Chooser.

Jade: A Different Approach

Where most templating engines take a very HTML-centric approach, Jade stands out by abstracting the details of HTML away from you. It is also worth noting that Jade is the brainchild of TJ Holowaychuk, the same person who brought us Express. It should come as no surprise, then, that Jade integration with Express is very good. The approach that Jade takes is very noble: at its core is the assertion that HTML is a fussy and tedious language to write by hand. Let’s take a look at what a Jade template looks like, along with the HTML it will output (taken from the Jade home page, and modified slightly to fit the book format):

doctype html <!DOCTYPE html>

html(lang="en") <html lang="en">

head <head>

title= pageTitle <title>Jade Demo</title>

script. <script>

if (foo) { if (foo) {

bar(1 + 5) bar(1 + 5)

} }

body </script>

<body>

h1 Jade <h1>Jade</h1>

#container <div id="container">

if youAreUsingJade

p You are amazing <p>You are amazing</p>

else

p Get on it!

p. <p>

Jade is a terse and Jade is a terse and

simple templating simple templating

language with a language with a

strong focus on strong focus on

performance and performance and

powerful features. powerful features.

</p>

</body>

</html>

Jade certainly represents a lot less typing: no more angle brackets or closing tags. Instead it relies on indentation and some common-sense rules, making it easier to say what you mean. Jade has an additional advantage: theoretically, when HTML itself changes, you can simply get Jade to retarget the newest version of HTML, allowing you to “future proof” your content.

As much as I admire the Jade philosophy and the elegance of its execution, I’ve found that I don’t want the details of HTML abstracted away from me. As a web developer, HTML is at the heart of everything I do, and if the price is wearing out the angle bracket keys on my keyboard, then so be it. A lot of frontend developers I talk to feel the same, so maybe the world just isn’t ready for Jade….

Here’s where we’ll part ways with Jade; you won’t be seeing it in this book. However, if the abstraction appeals to you, you will certainly have no problems using Jade with Express, and there are plenty of resources to help you do so.

Handlebars Basics

Handlebars is an extension of Mustache, another popular templating engine. I recommend Handlebars for its easy JavaScript integration (both frontend and backend) and familiar syntax. For me, it strikes all the right balances and is what we’ll be focusing on in this book. The concepts we’re discussing are broadly applicable to other templating engines, though, so you will be well prepared to try different templating engines if Handlebars doesn’t strike your fancy.

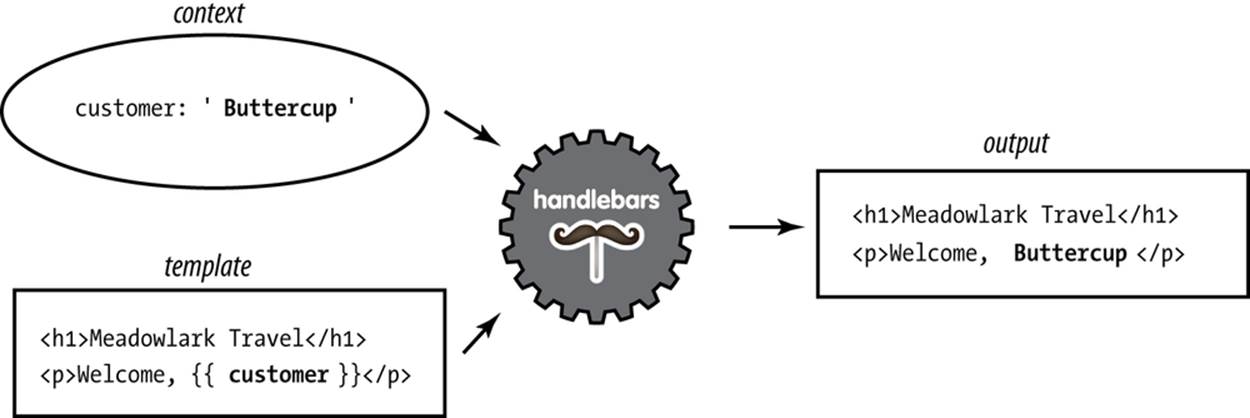

The key to understanding templating is understanding the concept of context. When you render a template, you pass the templating engine an object called the context object, and this is what allows replacements to work.

For example, if my context object is { name: 'Buttercup' }, and my template is <p>Hello, {{name}}!</p>, {{name}} will be replaced with Buttercup. What if you want to pass HTML to the template? For example, if our context was instead { name: '<b>Buttercup</b>' }, using the previous template will result in <p>Hello, <b>Buttercup<b></p>, which is probably not what you’re looking for. To solve this problem, simply use three curly brackets instead of two: {{{name}}}.

NOTE

While we’ve already established that we should avoid writing HTML in JavaScript, the ability to turn off HTML escaping with triple curly brackets has some important uses. For example, if you were building a CMS with WYSIWYG editors, you would probably want to be able to pass HTML to your views. Also, the ability to render properties from the context without HTML escaping is important for layouts and sections, which we’ll learn about shortly.

In Figure 7-1, we see how the Handlebars engine uses the context (represented by an oval) combined with the template to render HTML.

Figure 7-1. Rendering HTML with Handlebars

Comments

Comments in Handlebars look like {{! comment goes here }}. It’s important to understand the distinction between Handlebars comments and HTML comments. Consider the following template:

{{! super-secret comment }}

<!-- not-so-secret comment -->

Assuming this is a server-side template, the super-secret comment will never be sent to the browser, whereas the not-so-secret comment will be visible if the user inspects the HTML source. You should prefer Handlebars comments for anything that exposes implementation details, or anything else you don’t want exposed.

Blocks

Things start to get more complicated when you consider blocks. Blocks provide flow control, conditional execution, and extensibility. Consider the following context object:

{

currency: {

name: 'United States dollars',

abbrev: 'USD',

},

tours: [

{ name: 'Hood River', price: '$99.95' },

{ name: 'Oregon Coast', price, '$159.95' },

],

specialsUrl: '/january-specials',

currencies: [ 'USD', 'GBP', 'BTC' ],

}

Now let’s examine a template we can pass that context to:

<ul>

{{#each tours}}

{{! I'm in a new block...and the context has changed }}

<li>

{{name}} - {{price}}

{{#if ../currencies}}

({{../../currency.abbrev}})

{{/if}}

</li>

{{/each}}

</ul>

{{#unless currencies}}

<p>All prices in {{currency.name}}.</p>

{{/unless}}

{{#if specialsUrl}}

{{! I'm in a new block...but the context hasn't changed (sortof) }}

<p>Check out our <a href="{{specialsUrl}}">specials!</p>

{{else}}

<p>Please check back often for specials.</p>

{{/if}}

<p>

{{#each currencies}}

<a href="#" class="currency">{{.}}</a>

{{else}}

Unfortunately, we currently only accept {{currency.name}}.

{{/each}}

</p>

There’s a lot going on in this template, so let’s break it down. It starts off with the each helper, which allows us to iterate over an array. What’s important to understand is that between {{#each tours}} and {{/each tours}}, the context changes. On the first pass, it changes to { name: 'Hood River', price: '$99.95' }, and on the second pass, the context is { name: 'Oregon Coast', price: '$159.95' }. So within that block, we can refer to {{name}} and {{price}}. However, if we want to access the currency object, we have to use ../ to access the parent context.

If a property of the context is itself an object, we can access its properties as normal with a period, such as {{currency.name}}.

The if helper is special, and slightly confusing. In Handlebars, any block will change the context, so within an if block, there is a new context...which happens to be a duplicate of the parent context. In other words, inside an if or else block, the context is the same as the parent context. This is normally a completely transparent implementation detail, but it becomes necessary to understand when you’re using if blocks inside an each loop. In the loop {{#each tours}}, we can access the parent context with ../. However, in our {{#if ../currencies}} block, we have entered a new context…so to get at the currency object, we have to use ../../. The first ../ gets to the product context, and the second one gets back to the outermost context. This produces a lot of confusion, and one simple expedient is to avoid using if blocks within eachblocks.

Both if and each have an optional else block (with each, if there are no elements in the array, the else block will execute). We’ve also used the unless helper, which is essentially the opposite of the if helper: it executes only if the argument is false.

The last thing to note about this template is the use of {{.}} in the {{#each currencies}} block. {{.}} simply refers to the current context; in this case, the current context is simply a string in an array that we want to print out.

TIP

Accessing the current context with a lone period has another use: it can distinguish helpers (which we’ll learn about soon) from properties of the current context. For example, if you have a helper called foo and a property in the current context called foo, {{foo}} refers to the helper, and {{./foo}} refers to the property.

Server-Side Templates

Server-side templates allow you to render HTML before it’s sent to the client. Unlike client-side templating, where the templates are available for the curious user who knows how to view HTML source, your users will never see your server-side template, or the context objects used to generate the final HTML.

Server-side templates, in addition to hiding your implementation details, support template caching, which is important for performance. The templating engine will cache compiled templates (only recompiling and recaching when the template itself changes), which will improve the performance of templated views. By default, view caching is disabled in development mode and enabled in production mode. If you want to explicitly enable view caching, you can do so thusly: app.set('view cache', true);.

Out of the box, Express supports Jade, EJS, and JSHTML. We’ve already discussed Jade, and I find little to recommend EJS or JSHTML (neither go far enough, syntactically, for my taste). So we’ll need to add a node package that provides Handlebars support for Express:

npm install --save express3-handlebars

Then we’ll link it into Express:

var handlebars = require('express3-handlebars')

.create({ defaultLayout: 'main' });

app.engine('handlebars', handlebars.engine);

app.set('view engine', 'handlebars');

TIP

express3-handlebars expects Handlebars templates to have the .handlebars extension. I’ve grown used to this, but if it’s too wordy for you, you can change the extension to the also common .hbs when you create the express3-handlebars instance: require('express3-handlebars').create({ extname: '.hbs' }).

Views and Layouts

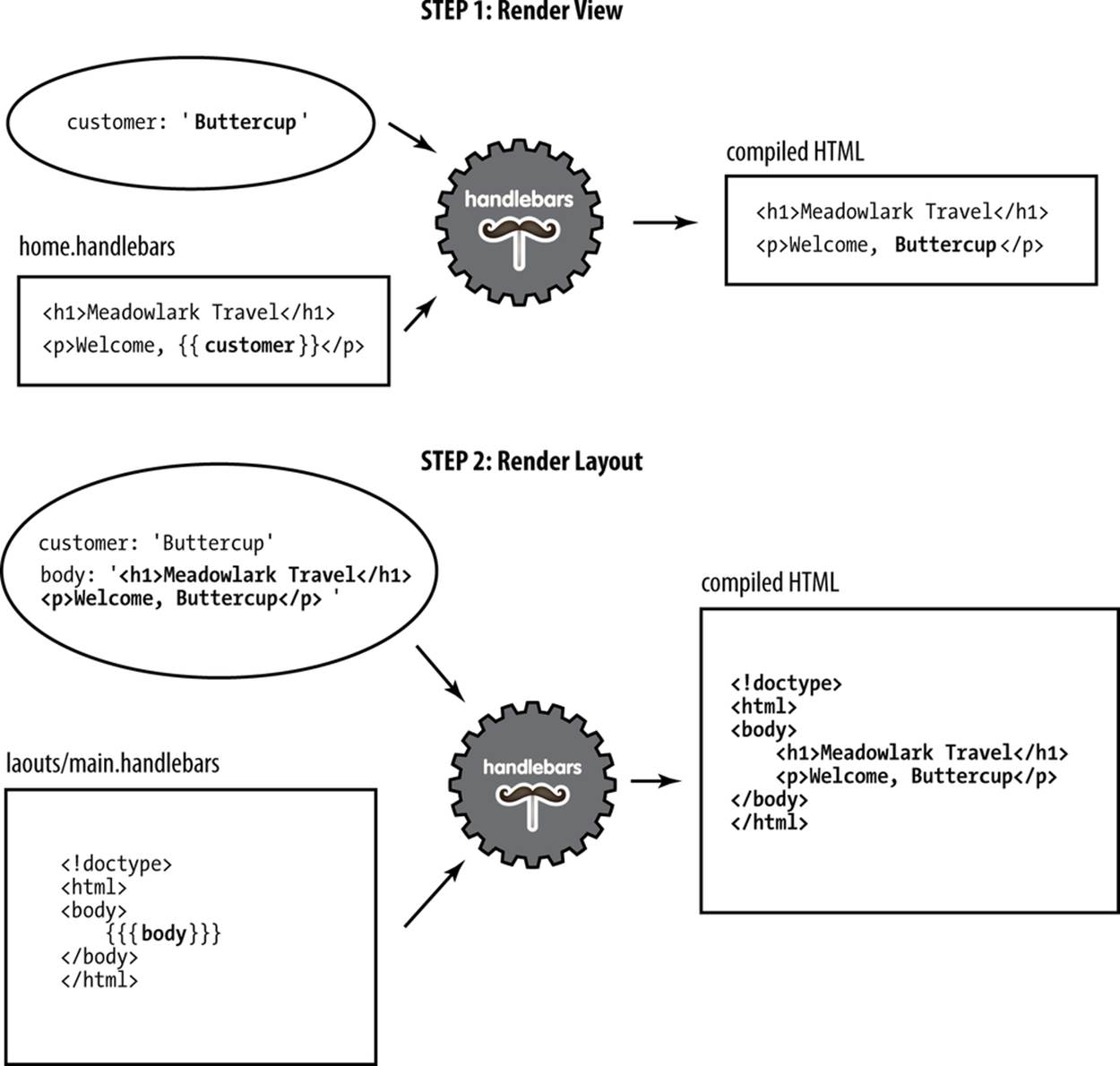

A view usually represents an individual page on your website (though it could represent an AJAX-loaded portion of a page, or an email, or anything else for that matter). By default, Express looks for views in the views subdirectory. A layout is a special kind of view—essentially, a template for templates. Layouts are essential because most (if not all) of the pages on your site will have an almost identical layout. For example, they must have an <html> element and a <title> element, they usually all load the same CSS files, and so on. You don’t want to have to duplicate that code for every single page, which is where layouts come in. Let’s look at a bare-bones layout file:

<!doctype>

<html>

<head>

<title>Meadowlark Travel</title>

<link rel="stylesheet" href="/css/main.css">

</head>

<body>

{{{body}}}

</body>

</html>

Notice the text inside the <body> tag: {{{body}}}. That’s so the view engine knows where to render the content of your view. It’s important to use three curly brackets instead of two: our view is most likely to contain HTML, and we don’t want Handlebars trying to escape it. Note that there’s no restriction on where you place the {{{body}}} field. For example, if you were building a responsive layout in Bootstrap 3, you would probably want to put your view inside a container <div>. Also, common page elements like headers and footers usually live in the layout, not the view. Here’s an example:

<!-- ... -->

<body>

<div class="container">

<header><h1>Meadowlark Travel</h1></header>

{{{body}}}

<footer>© {{copyrightYear}} Meadowlark Travel</footer>

</div>

</body>

In Figure 7-2, we see how the template engine combines the view, layout, and context. The important thing that this diagram makes clear is the order of operations. The view is rendered first, before the layout. At first, this may seem counterintuitive: the view is being rendered inside the layout, so shouldn’t the layout be rendered first? While it could technically be done this way, there are advantages to doing it in reverse. Particularly, it allows the view itself to further customize the layout, which will come in handy when we discuss sections.

NOTE

Because of the order of operations, you can pass a property called body into the view, and it will render correctly in the view. However, when the layout is rendered, the value of body will be overwritten by the rendered view.

Figure 7-2. Rendering a view with a layout

Using Layouts (or Not) in Express

Chances are, most (if not all) of your pages will use the same layout, so it doesn’t make sense to keep specifying the layout every time we render a view. You’ll notice that when we created the view engine, we specified the name of the default layout:

var handlebars = require('express3-handlebars')

.create({ defaultLayout: 'main' });

By default, Express looks for views in the views subdirectory and layouts in views/layouts. So if you have a view views/foo.handlebars, you can render it this way:

app.get('/foo', function(req, res){

res.render('foo');

});

It will use views/layouts/main.handlebars as the layout. If you don’t want to use a layout at all (meaning you’ll have to have all of the boilerplate in the view), you can specify layout: null in the context object:

app.get('/foo', function(req, res){

res.render('foo', { layout: null });

});

Or, if we want to use a different template, we can specify the template name:

app.get('/foo', function(req, res){

res.render('foo', { layout: 'microsite' });

});

This will render the view with layout views/layouts/microsite.handlebars.

Keep in mind that the more templates you have, the more basic HTML layout you have to maintain. On the other hand, if you have pages that are substantially different in layout, it may be worth it: you have to find a balance that works for your projects.

Partials

Very often, you’ll have components that you want to reuse on different pages (often called “widgets” in frontend circles). One way to achieve that with templates is to use partials (so named because they don’t render a whole view or a whole page). Let’s imagine we want a Current Weather component that displays the current weather conditions in Portland, Bend, and Manzanita. We want this component to be reusable so we can easily put it on whatever page we want, so we’ll use a partial. First, we create a partial file, views/partials/weather.handlebars:

<div class="weatherWidget">

{{#each partials.weather.locations}}

<div class="location">

<h3>{{name}}</h3>

<a href="{{forecastUrl}}">

<img src="{{iconUrl}}" alt="{{weather}}">

{{weather}}, {{temp}}

</a>

</div>

{{/each}}

<small>Source: <a href="http://www.wunderground.com">Weather

Underground</a></small>

</div>

Note that we namespace our context by starting with partials.weather: since we want to be able to use the partial on any page, it’s not practical to pass the context in for every view, so instead we use res.locals (which is available to every view). But because we don’t want to interfere with the context specified by individual views, we put all partial context in the partials object.

In Chapter 19, we’ll see how to get current weather information from the free Weather Underground API. For now, we’re just going to use dummy data. In our application file, we’ll create a function to get current weather data:

function getWeatherData(){

return {

locations: [

{

name: 'Portland',

forecastUrl: 'http://www.wunderground.com/US/OR/Portland.html',

iconUrl: 'http://icons-ak.wxug.com/i/c/k/cloudy.gif',

weather: 'Overcast',

temp: '54.1 F (12.3 C)',

},

{

name: 'Bend',

forecastUrl: 'http://www.wunderground.com/US/OR/Bend.html',

iconUrl: 'http://icons-ak.wxug.com/i/c/k/partlycloudy.gif',

weather: 'Partly Cloudy',

temp: '55.0 F (12.8 C)',

},

{

name: 'Manzanita',

forecastUrl: 'http://www.wunderground.com/US/OR/Manzanita.html',

iconUrl: 'http://icons-ak.wxug.com/i/c/k/rain.gif',

weather: 'Light Rain',

temp: '55.0 F (12.8 C)',

},

],

};

}

Now we’ll create a middleware to inject this data into the res.locals.partials object (we’ll learn more about middleware in Chapter 10):

app.use(function(req, res, next){

if(!res.locals.partials) res.locals.partials = {};

res.locals.partials.weather = getWeatherData();

next();

});

Now that everything’s set up, all we have to do is use the partial in a view. For example, to put our widget on the home page, edit views/home.handlebars:

<h2>Welcome to Meadowlark Travel!</h2>

{{> weather}}

The {{> partial_name}} syntax is how you include a partial in a view: express3-handlebars will know to look in views/partials for a view called partial_name.handlebars (or weather.handlebars, in our example).

TIP

express3-handlebars supports subdirectories, so if you have a lot of partials, you can organize them. For example, if you have some social media partials, you could put them in the views/partials/social directory and include them using {{> social/facebook}}, {{> social/twitter}}, etc.

Sections

One technique I’m borrowing from Microsoft’s excellent Razor template engine is the idea of sections. Layouts work well if all of your view fits neatly within a single element in your layout, but what happens when your view needs to inject itself into different parts of your layout? A common example of this is a view needing to add something to the <head> element, or to insert a <script> that uses jQuery (meaning it needs to come after jQuery is referenced, which is sometimes the very last thing in the layout, for performance reasons).

Neither Handlebars nor express3-handlebars has a built-in way to do this. Fortunately, Handlebars helpers make this really easy. When we instantiate the Handlebars object, we’ll add a helper called section:

var handlebars = require('express3-handlebars').create({

defaultLayout:'main',

helpers: {

section: function(name, options){

if(!this._sections) this._sections = {};

this._sections[name] = options.fn(this);

return null;

}

}

});

Now we can use the section helper in a view. Let’s add a view (views/jquery-test.handlebars) to add something to the <head> and a script that uses jQuery:

{{#section 'head'}}

<!-- we want Google to ignore this page -->

<meta name="robots" content="noindex">

{{/section}}

<h1>Test Page</h1>

<p>We're testing some jQuery stuff.</p>

{{#section 'jquery'}}

<script>

$('document').ready(function(){

$('h1').html('jQuery Works');

});

</script>

{{/section}}

Now in our layout, we can place the sections just as we place {{{body}}}:

<!doctype html>

<html>

<head>

<title>Meadowlark Travel</title>

{{{_sections.head}}}

</head>

<body>

{{{body}}}

<script src="http://code.jquery.com/jquery-2.0.2.min.js"></script>

{{{_sections.jquery}}}

</body>

</html>

Perfecting Your Templates

Your templates are at the heart of your website. A good template structure will save you development time, promote consistency across your website, and reduce the number of places that layout quirks can hide. To achieve these benefits, though, you must spend some time crafting your templates carefully. Deciding how many templates you should have is an art: generally, fewer is better, but there is a point of diminishing returns, depending on the uniformity of your pages. Your templates are also your first line of defense against cross-browser compatibility issues and valid HTML. They should be lovingly crafted and maintained by someone who is well versed in frontend development. A great place to start—especially if you’re new—is HTML5 Boilerplate. In the previous examples, we’ve been using a minimal HTML5 template to fit the book format, but for our actual project, we’ll be using HTML5 Boilerplate.

Another popular place to start with your template are third-party themes. Sites like Themeforest and WrapBootstrap have hundreds of ready-to-use HTML5 themes that you can use as a starting place for your template. Using a third-party theme starts with taking the primary file (usuallyindex.html) and renaming it to main.handlebars (or whatever you choose to call your layout file), and placing any resources (CSS, JavaScript, images) in the public directory you use for static files. Then you’ll have to edit the template file and figure out where you want to put the{{{body}}} expression. Depending on the elements of your template, you may want to move some of them into partials. A great example is a “hero” (a tall banner designed to grab the user’s attention. If the hero appears on every page (probably a poor choice), you would leave the hero in the template file. If it appears on only one page (usually the home page), then it would go only in that view. If it appears on several—but not all—pages, then you might consider putting it in a partial. The choice is yours, and herein lies the artistry of making a unique, captivating website.

Client-Side Handlebars

Client-side templating with handlebars is useful whenever you want to have dynamic content. Of course our AJAX calls can return HTML fragments that we can just insert into the DOM as-is, but client-side Handlebars allows us to receive the results of AJAX calls as JSON data, and format it to fit our site. For that reason, it’s especially useful for communicating with third-party APIs, which are going to return JSON, not HTML formatted to fit your site.

Before we use Handlebars on the client side, we need to load Handlebars. We can either do that by putting Handlebars in with our static content or using an already available CDN. We’ll be using the latter approach in views/nursery-rhyme.handlebars:

{{#section 'head'}}

<script src="//cdnjs.cloudflare.com/ajax/libs/handlebars.js/1.3.0/handlebars.min.js"></script>

{{/section}}

Now we’ll need somewhere to put our templates. One way is to use an existing element in our HTML, preferably a hidden one. You can accomplish this by putting your HTML in <script> elements in the <head>. It seems odd at first, but it works quite well:

{{#section 'head'}}

<script src="//cdnjs.cloudflare.com/ajax/libs/handlebars.js/1.3.0/handlebars.min.js"></script>

<script id="nurseryRhymeTemplate" type="text/x-handlebars-template">

Marry had a little <b>\{{animal}}</b>, its <b>\{{bodyPart}}</b>

was <b>\{{adjective}}</b> as <b>\{{noun}}</b>.

</script>

{{/section}}

Note that we have to escape at least one of the curly brackets; otherwise, server-side view processing would attempt to make the replacements instead.

Before we use the template, we have to compile it:

{{#section 'jquery'}}

$(document).ready(function(){

var nurseryRhymeTemplate = Handlebars.compile(

$('#nurseryRhymeTemplate').html());

});

{{/section}}

And we’ll need a place to put the rendered template. For testing purposes, we’ll add a couple of buttons, one to render directly from our JavaScript, the other to render from an AJAX call:

<div id="nurseryRhyme">Click a button....</div>

<hr>

<button id="btnNurseryRhyme">Generate nursery rhyme</button>

<button id="btnNurseryRhymeAjax">Generate nursery rhyme from AJAX</button>

And finally the code to render the template:

{{#section 'jquery'}}

<script>

$(document).ready(function(){

var nurseryRhymeTemplate = Handlebars.compile(

$('#nurseryRhymeTemplate').html());

var $nurseryRhyme = $('#nurseryRhyme');

$('#btnNurseryRhyme').on('click', function(evt){

evt.preventDefault();

$nurseryRhyme.html(nurseryRhymeTemplate({

animal: 'basilisk',

bodyPart: 'tail',

adjective: 'sharp',

noun: 'a needle'

}));

});

$('#btnNurseryRhymeAjax').on('click', function(evt){

evt.preventDefault();

$.ajax('/data/nursery-rhyme', {

success: function(data){

$nurseryRhyme.html(

nurseryRhymeTemplate(data))

}

});

});

});

</script>

{{/section}}

And route handlers for our nursery rhyme page and our AJAX call:

app.get('/nursery-rhyme', function(req, res){

res.render('nursery-rhyme');

});

app.get('/data/nursery-rhyme', function(req, res){

res.json({

animal: 'squirrel',

bodyPart: 'tail',

adjective: 'bushy',

noun: 'heck',

});

});

Essentially, Handlebars.compile takes in a template, and returns a function. That function accepts a context object and returns a rendered string. So once we’ve compiled our templates, we have reusable template renderers that we just call like functions.

Conclusion

We’ve seen how templating can make your code easier to write, read, and maintain. Thanks to templates, we don’t have to painfully cobble together HTML from JavaScript strings: we can write HTML in our favorite editor and use a compact and easy-to-read templating language to make it dynamic.

[7] To paraphrase my friend and mentor, Paul Inman.