RaphaelJS: Graphics and Visualization on the Web (2014)

Chapter 3. Interaction

Chances are good that you aspire to create something beyond the kindergarten-level shapes we covered in the previous chapter. Don’t worry—Raphael handles complex shapes just fine (that was originally the subject of this chapter). But I wanted to skip straight to the interactive aspect of Raphael because it’s what makes the library so incredibly powerful. You can make as beautiful an image in Photoshop as you like, but you need Raphael to make it dance on demand.

You may recall that, at the end of the braille example in the previous chapter, we created an input box and a button to trigger the function that drew the dots. It looked like this:

<input id="message" style="width: 200px" value="Raphael is great"/>

<input id="clickme" type="button" value="braille-ify" />

<script>

function make() {

// make the braille

};

// click event to invoke function

document.getElementById("clickme").onclick = make;

</script>

This is the most basic method for creating interactions in JavaScript. It consists of three parts: First is the event—in this case, a click of the mouse. Second is the object on the page we want to update when the event occurs, which in this case is the button. Last is the function that should fire when the even occurs in the context of the specified element. In this case, that function is make.

When we want to control our Raphael objects from the page using regular old HTML objects—buttons, dropdown menus, check boxes, radio buttons—then this is how we do it: by assigning (or “registering”) a given event to a certain object and pairing them with a function that manipulates our Raphael objects however we like. In the above example, that function read the contents of the input box and translated it into braille. This is extremely convenient for any sort of visualization or graphic where users are invited to slide bars or click buttons to manipulate the number of Raphael objects or their positions.

In many cases, however, we want to allow the user to interact with Raphael objects themselves, clicking shapes, mousing over paths, and so forth. In Chapter 2, we briefly touched on the .node property that transforms a Raphael object into its “physical” counterpart on the page—from shadow to body. Using the node property, one could theoretically register events on it the same way we controlled the button click above.

But that would be a pain, and this book takes a strong stance against sadism. Fortunately, Raphael comes with in-house methods for handling interactions that make life much easier. If you’re familiar with jQuery or any other JavaScript helper library, then events in Raphael will look familiar. If not, they’ll look familiar soon.

Raphael Events: The Basics

Let’s make a red square, and then attach an event to make it turn blue when we click it:

var paper = Raphael(0, 0, 500, 500);

var mysquare = paper.rect(25, 25, 250, 250).attr("fill", "red");

mysquare.click(function(e) {

this.attr("fill", "blue");

});

As you can see, .click() is a method you attach to a Raphael object that creates an event. The argument passed to .click() is the function to fire when the user clicks on the object.

Now would be a good time to remind ourselves that, unlike many languages, functions in JavaScript are themselves objects, just like integers, arrays, and strings. Like those other types of variables, you can declare them and then pass them to other functions. You could equally accomplish the above example like this:

var paper = Raphael(0, 0, 500, 500);

var mysquare = paper.rect(25, 25, 250, 250).attr("fill", "red");

function turnMeBlue(e) {

this.attr("fill", "blue");

}

mysquare.click(turnMeBlue);

See this code live on jsFiddle.

I prefer the former method, which uses an “anonymous” function, because it’s one fewer variable to deal with. But you’ll occassionally want to declare a function independently and attach it to several different events. It’s mostly a stylistic choice.

To make the event a mouseover instead of a click, just use the .mouseover() method:

var paper = Raphael(0, 0, 500, 500);

var mysquare = paper.rect(25, 25, 250, 250).attr("fill", "red");

mysquare.mouseover(function(e) {

this.attr("fill", "blue");

});

In terms of user experience, I find this program wanting. Let’s at least restore the square to its original red color when the user’s mouse leaves its premises.

var paper = Raphael(0, 0, 500, 500);

var mysquare = paper.rect(25, 25, 250, 250).attr("fill", "red");

mysquare.mouseover(function(e) {

this.attr("fill", "blue");

});

mysquare.mouseout(function(e) {

this.attr("fill", "red");

});

You can “chain” events to save a few keystrokes:

var paper = Raphael(0, 0, 500, 500);

var mysquare = paper.rect(25, 25, 250, 250).attr("fill", "red");

mysquare.mouseover(function(e) {

this.attr("fill", "blue");

}).mouseout(function(e) {

this.attr("fill", "red");

});

Removing Events

There may come a time when you want to disable an event handler when the page reaches some state. Each event method has a corresponding method to undo it: unclick() for click(), unmouseout() for mouseout(), and so forth.

The un functions take as an argument the function assigned to the original event, so you don’t want to use anonymous functions for events you’ll need to undo later. The following example disables the square’s mouseover functionality when the user clicks on it:

var paper = Raphael(0, 0, 500, 500);

var mysquare = paper.rect(25, 25, 250, 250).attr("fill", "red");

var mover = function() {

this.attr("fill", "blue");

}

var mout = function() {

this.attr("fill", "red");

}

mysquare.mouseover(mover).mouseout(mout).click(function(e) {

this.attr("fill", "green");

this.unmouseover(mover);

this.unmouseout(mout);

});

I don’t find too many occasions where I need to remove events altogether. What’s more likely is that you will want to disable them only under certain circumstances, such as when the user has chosen to disable them. You can effectively disable an event handler without removing it by returning the value false, like so:

<input id="on_off" type="button" value="Hover ON" />

<div id="canvas"><div>

<script>

var hover_enabled = true;

function toggleHover() {

if (hover_enabled) {

this.value = "Hover OFF";

hover_enabled = false;

} else {

this.value = "Hover ON";

hover_enabled = true;

}

}

document.getElementById("on_off").onclick = toggleHover();

var paper = Raphael("canvas", 500, 500);

var mysquare = paper.rect(25, 25, 250, 250).attr("fill", "red");

var mover = function() {

if (!hover_enabled) {

return false;

}

this.attr("fill", "blue");

}

var mout = function() {

if (!hover_enabled) {

return false;

}

this.attr("fill", "red");

}

</script>

Events and Sets

Like attributes, events can be applied to sets of objects:

var paper = new Raphael(0, 0, 500, 500);

var square = paper.rect(200, 10, 50, 70).attr("fill", "steelblue");

var circle = paper.circle(120, 110, 25).attr("fill", "yellow");

var ellipse = paper.ellipse(60, 150, 30, 15).attr("fill", "orange");

var stuff = paper.set();

stuff.push(square, circle, ellipse);

var label = paper.text(10, 10, "Mouse over an object").attr("text-anchor", "start");

stuff.mouseover(function(e) {

label.attr("text", this.attr("fill"));

}).mouseout(function(e) {

label.attr("text", "Mouse over an object");

});

See this code live on jsFiddle.

When you mouse over a shape here, the text object we made in the upper-left corner updates to list the color of whichever one we just clicked. This is an important point: the this inside the function refers not the set of objects, but to whichever individual one you clicked on. This is because sets in Raphael are “psuedo objects”—phantasmal JavaScript objects that bind elements but have no counterpart on the page.

The .mouseover() and .mouseout() events are extremely useful for creating “tooltips”—boxes that pop up when you mouse over an object that offer some information about that object. In the example above, we essentially did this with a simple text tooltip that remains in the upper-left corner.

To make the text follow the mouse, we need to glean the coordinates of the cursor at the moment it enters the shapes and each moment while it’s moving around over the shape. You may notice that there’s a variable e that gets passed to the anonymous function inside the mouseover event. Every event has a variable like this that contains information about the event, like where the mouse is on the screen when it’s fired and what object the user interacted with to trigger the event. We don’t actually use e in the previous example, but I always include it out of habit since it’s so useful.

NOTE

Note that this variable does not automatically exist; you have to pass it to the anonymous function. You can call this variable whatever you like. Most people use e or evt or something similar to remind themselves that it contains information about the event.

The event variable has, among many properties, two called .clientX and .clientY that indicate the coordinates of the mouse at the precise moment when the event fired.

To make this label a tooltip, we merely have to update its x and y coordinates according to the mouse position:

stuff.mouseover(function(e) {

label.attr({

text: this.attr("fill")),

x: e.clientX,

y: e.clientY

});

});

This is a nice upgrade to the user experience, but we’re not quite there. While a user’s mouse is inside a shape, the label just hangs out at the exact point where the cursor entered the shape’s domain. To improve the experience, let’s attach the movement of the tooltip to the mousemove()event, which will fire every time the mouse moves while inside the element to which the event is attached. We’ll also return the label to its original position in the corner when the mouse leaves the shape.

stuff.mouseover(function(e) {

label.attr("text", this.attr("fill"));

}).mousemove(function(e) {

label.attr({

x: e.clientX + 10,

y: e.clientY

});

}).mouseout(function(e) {

label.attr({

x: 10,

y: 10,

text: "Mouse over an object"

});

});

You may notice I made one other small improvement: I’m placing the tooltip 10 pixels to the right of the mouse position. This is because, otherwise, it’s very easy for the mouse to “trip” over the tooltip itself, prematurely triggering the mouseout event since the cursor is technically leaving the domain of the shape to enter the domain of the tooltip itself. This is useful to remember: the mouse events we attach to a shape do not apply whenever the mouse is inside the bounds of that shape, but rather when the mouse is directly interacting with the shape.

In addition to .click(), .mouseover(), and .mouseout(), Raphael offers the following events: .mousedown(), .mouseup(), .mousemove(), .dblclick(), and .drag(). That last one is a little more complicated, but the others work the same way as a .click(). Let’s look at another example.

Drag Events

You could technically make click and drag behavior only with the mouseup, mousedown, and mousemove events, using variables outside the scope of the event handler functions to track when the mouse was pressed on an object and when it was released. In that sense, the drag event is really just a “convenience method” to avoid all that repetitive coding. (You might argue that all of Raphael is really just one large convenience method for the pain of manipulating DOM events. For more discussion of the deep philosophical underpinnings of Raphael, you’ll have to wait for the sequel to this book.)

The drag function takes three arguments, all functions: the handlers for the start of the drag, the movement of the mouse during the drag, and the end of the drag:

var paper = new Raphael(0, 0, 500, 500);

var circle = paper.circle(120, 110, 25).attr("fill", "yellow");

circle.drag(dragstart, dragmove, dragend);

If we consult the Raphael documentation for the drag event, we see that these three functions each come with different arguments:

function dragstart(x, y, e) {}

function dragmove(dx, dy, x, y, e) {}

function dragend(e) {}

For all three functions, the e variable is the same event variable we see in the other types of handlers. Additionally, x and y in the first two functions record the current position of the mouse. In the second function, dx and dy represent the difference in mouse position between x and y and the original position of the mouse.

Like the e argument we discussed above, these are arguments that you are resposible for passing to the handlers, and you can name them whatever you like. Whatever variables you pass to the dragmove function, for example, Raphael will understand the first one to be the dx value, the second to be the dy value, and so forth. There isn’t usually much reason to invent a different naming convention.

Here is how we make a draggable circle:

var paper = new Raphael(0, 0, 500, 500);

var circle = paper.circle(120, 110, 25).attr("fill", "yellow");

circle.drag(dragmove, dragstart, dragend);

function dragmove(dx, dy, x, y, e) {

this.attr({

cx: x,

cy: y

});

}

function dragstart(x, y, e) {

this.attr("fill", "orange");

}

function dragend(e) {

this.attr("fill", "yellow");

}

See this code live on jsFiddle.

We’re using the dragstart and dragend functions here to turn the circle orange while it’s being dragged and to return it to its yellow color when the mouse is released. Meanwhile, dragmove is firing several times a second so long as the mouse is moving, resetting the center position to the position of the mouse so that the circle drags along with the mouse.

Observant readers will notice that dragmove comes before dragstart in the order of functions that .drag() accepts, which seems to violate common sense. The reason is that the event handler for mouse movements is the only one we absolutely need to make a drag work. In fact, in the above example, the only thing the start and stop functions are accomplishing is changing the color. We’ll see in just a moment how we can put them to better use.

Better Dragging

The above example is a good start, but there are a few things I don’t like about it. First, it behaves a little differently depending on where in the circle you initially click, since it resets the center of the shape to that point whether you click the very edge or the precise center. The code is also only useful for circles and ellipses, which have cx and cy properties. Attempting to apply this code to a rectangle would be useless.

Instead, let’s use the transform() method we learned in the previous chapter. There are a few different ways we could do this. I’m going to skip straight to the best one:

var paper = new Raphael(0, 0, 500, 500);

var circle = paper.circle(120, 110, 25).attr("fill", "yellow");

circle.drag(dragmove, dragstart, dragend);

function dragstart(x, y, e) {

// save the value of the transformation at the start of the drag

// if this is the initial drag, it will be a blank string

this.current_transform = this.transform();

// just for kicks

this.attr("fill", "orange");

}

function dragmove(dx, dy, x, y, e) {

// adjust the pre-existing transformation (if any) by the drag difference

this.transform(this.current_transform+'T'+dx+','+dy);

}

function dragend(e) {

// update the current transformation with the final value

this.current_transform = this.transform();

// that's enough kicks

this.attr("fill", "yellow");

}

Transformations, we should recall, overwrite any previous transformations on the element. Consider the following code:

var paper = Raphael(0, 0, 500, 500);

paper.ellipse(300, 200, 50, 20)

.attr("fill", "green")

.transform("T5000,1000")

.transform("T50,10");

This does not place the center of the ellipse at (5350,1210). It places it at (100,30), since the second transformation overwrites the first (absurd) one. In this sense, transformations operate like CSS: applying two colors to an element doesn’t mix them, it uses the second one.

If we only used the dragmove function, the drag would only work once. Dragging it a second time would reset the position to the original one. By dutifully recording the last known position at the end of each drag and adding it to the next one, we get a fully mobile object. Not only is it responsive to where on the object we click, this precise strategy works for any shape—circles, squares, and more complex shapes that we’ll learn about in the next chapter. Better yet, it works on all of those types at once when those shapes are bundled in a set.

Dragging Sets

If you check out the Raphael section of a coding forum like Stack Overflow—what else is there to do on a Saturday night?—one of the most common questions you will see is how to make sets of objects draggable. This comes up all the time with browser games and complex user interfaces.

People come up with all sorts of hilariously intricate solutions that involve iterating though each item in the list, calculating where it needs to be, and individually moving it. I’m here to tell you that there is a better way.

First, let’s make one improvement to the above example. Right now, we’re assigning the transformation as a property of the object this, the same way we might give any object in JavaScript a property. In general, I don’t think it’s a great idea to be adding properties to objects you didn’t create from scratch—particularly ones with lots of awesome properties like Raphael objects—since there is always the chance that you will overwrite some pre-existing property or method. Of more direct relevance to us is that assigning a property to a set in Raphael does not transfer that property to each constituent item. That only works when performing a standard Raphael operation. Fortunately, Raphael has precisely the function we need: .data().

The .data() method stores arbitrary values in keys, very similar to the way information is stored in regular JS objects, but with a slightly more burdensome syntax.

// old way

this.current_transform = this.transform();

console.log(this.current_transform);

// better way

this.data("current_transform") = this.transform();

console.log(this.data("current_transform"));

Like .attr(), .transform(), and most other Raphael methods, leaving out the second argument turns .data() from an assignment to a retrieval. With that in mind, let’s make a draggable set of heterogeneous objects—say, a face from a six-sided die.

var paper = Raphael(0, 0, 500, 500);

var dice = paper.set();

// rectangle with rounded edges

dice.push(paper.rect(10, 10, 60, 60, 4).attr("fill", "#FFF"));

dice.push(paper.circle(22, 58, 5).attr("fill", "#000"));

dice.push(paper.circle(58, 22, 5).attr("fill", "#000"));

dice.push(paper.circle(40, 40, 5).attr("fill", "#000"));

dice.push(paper.circle(22, 22, 5).attr("fill", "#000"));

dice.push(paper.circle(58, 59, 5).attr("fill", "#000"));

The construction of the die is pretty straightforward save for one small new concept. A .rect() object can take a fifth argument that rounds the corners with a radius of the given number of pixels. Note that we have a white background to the die face as well. It doesn’t make any visual difference so long as the page itself is white, but it makes a huge behavioral difference. Without a filling, Raphael considers the object to be empty, and thus clicking inside it has no effect. The dragging event would not work because there there would not be anything for the mouse to hold on to.

We’re going to be attaching the drag events to this set. But as I so presciently pointed out earlier, an event attached to a set still fires only on the specific element that the user clicks. We need to make sure that the drag functionality applies to every piece of the set simultaneously.

At this point, you may be thinking, “Easy, I’ll just perform the transformation on the variable dice from inside the event function.” Sure, that would work—so long as there is there is only ever one die on the page. I don’t know what sort of lame games you like to play, but the ones I play have two. Do you really want to keep track of a different variable for each die?

No, you don’t. You want some way for the children of a set to locate their parent. For that, we’ll use the .data() method to give the items a property called myset.

// pair the objects in the set to the set itself

dice.data("myset", dice);

Then it’s a matter of locating the child element’s parent and operating on it. Transformations are always relative to an object’s original position, so the transformation will be identical on each item. Because of that, we can use the transformation of any object and apply it to the whole group.

dice.drag(

function(dx, dy, x, y, e) {

//dragmove

var myset = this.data("myset");

myset.transform(this.data("mytransform")+'T'+dx+','+dy);

},

function(x, y, e) {

//dragstart

var myset = this.data("myset");

myset.data("mytransform", this.transform());

},

function(e) {

//dragend

var myset = this.data("myset");

myset.data("mytransform", this.transform());

}

);

See this code live on jsFiddle.

I used three anonymous functions there for the sake of variety, but we could actually save a few lines by declaring the functions separately, since the start and end functions are identical. Now let’s get creative!

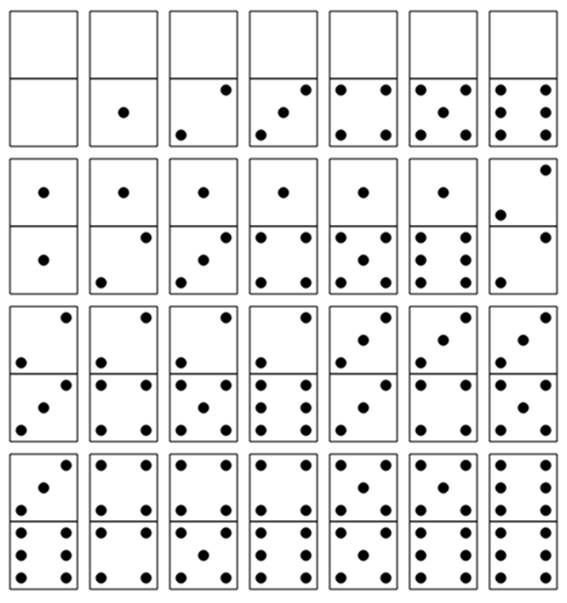

Case Study: Let’s Play Dominoes

I always thought the purpose of dominoes was to line them up on their sides and knock them over, particularly if it was your little sister who set them up. But apparently it’s also a nonviolent game. Let’s make a set. (I like this example because we can reuse a lot of the same code from the braille section.)

Wikipedia tells us that “the traditional set of dominoes contains one unique piece for each possible combination of two ends with zero to six spots.” Let’s begin by repurposing the function that constructs a letter of braille to make a die face, which requires nine positions instead of six:

1 4 7

2 5 8

3 6 9

I find it easier to just write out the patterns than to write a function to generate them, but feel free to do it the hard way on your own time. Like the braille example, RADIUS will refer to the size of the dots and SPACING will refer to the space between them. Thus, each half of a piece will have a width of 3 * SPACING.

var paper = Raphael(0,0,900,900),

SPACING = 18,

RADIUS = 4;

var patterns = [

"", // 0 dots

"5", // 1 dot

"3-7", // 2 dots

"3-5-7", // 3 dots

"1-3-7-9", // 4 dots

"1-3-5-7-9", // 5 dots

"1-2-3-7-8-9" // 6 dots

];

We’ll use nearly the exact same functions for the pips and individual squares, merely adding a square outline and adjusting the spacing a bit. We’ll be calling the make_face() function twice for each individual domino tile.

function make_dot(number) {

number -= 1;

if (number < 0 || number > 9) {

console.log("Invalid number.");

return null;

}

// first, second, or third column

var x = Math.floor(number / 3);

// first, second, or third row of that column

var y = number % 3;

var dot = paper.circle(x * SPACING + SPACING / 2, y * SPACING + SPACING / 2, RADIUS).attr("fill", "black");

return dot;

}

function make_face(dots) {

if (typeof dots === "string") {

dots = dots.split("-");

}

var tile = paper.set();

//square

tile.push(paper.rect(0, 0, SPACING * 3, SPACING * 3).attr({ fill: "#FFF"}));

//dots

for (var c = 0; c < dots.length; c += 1) {

tile.push(make_dot(dots[c]));

}

return tile;

}

The next part will be a little fancier. Instead of using the .data() property, we’re going to store all the information we need about each tile in a closure—variables that live inside a function that returns an object. Objects in closures are protected like private properties of a class in languages like Java or C. For a thorough discussion of closures, refer to Chapter Four of your copy of JavaScript: The Good Parts.

The end result will be to create an object with functions to move and rotate the tiles. Here’s the first part:

function tile(num_dots_top, num_dots_bottom, x, y, a) {

if (typeof(num_dots_top) === "undefined" || typeof(num_dots_top) ===

"undefined") {

console.log("You must supply values for both sides of the tile.");

return null;

}

// positional info. Defaults

var pos = { x: x || 0, y: y || 0, a: a || 0 },

centroid = { x: pos.x + SPACING * 1.5, y: pos.y + SPACING * 3 };

// Raphael objects

var top = make_face(patterns[num_dots_top]),

bottom = make_face(patterns[num_dots_bottom]),

piece = paper.set([top, bottom]);

// function to place piece at x,y location, rotated to angle a (in degrees)

var move = function(x, y, a) {

pos = {x: x, y: y, a: a};

centroid = { x: pos.x + SPACING * 1.5, y: pos.y + SPACING * 3 };

top.transform("T" + x + "," + y + "R" + a + "," + centroid.x + "," + centroid.y);

y += SPACING * 3;

bottom.transform("T" + x + "," + y + "R" + a + "," + centroid.x + "," + centroid.y);

};

// initial position

move(pos.x, pos.y, pos.a);

The (as yet incomplete) tile() function will be called once each time we need a new tile. The tiles’ coordinates and its rotation are stored in the pos object. This function will make internal use of the nested move() function to get the piece where we want it and rotate it to the desired angle using both the T and R transformations.

Each time the move function is called, we update the pos variable and recalculate the coordinates of the center of the tile, which we will need for the axis of rotation. Then the function moves the top half of the piece. We’ll deal with compound transformations in more detail later, but this one is pretty straightforward. First, we move the top square to the given x and y coordinates, then we rotate it around the center point that we just calculated.

Since the bottom tile needs to appear under the top one, let’s add 3 * SPACING to the y value before running the same transformation; we update y instead of pos.y so as not to modify the stored position of the tile.

Now let’s add a drag capability. We want to be able to use the move() variable to drag objects as well, but there’s a small hitch: The function updates the position of the tile each time it executes, but the dx and dy variables represent the total amount of distance the mouse has moved since the drag began. If we were to update the position of the tile with each call of dragmove, the tile would very quickly fly off the screen.

Easily solved: we just need the function to remember where it was when the drag began.

// drag variables

var dragx, dragy;

// drag handlers

var dragstart = function(x, y, e) {

dragx = pos.x;

dragy = pos.y;

};

var dragmove = function(dx, dy, x, y, e) {

move(dragx + dx, dragy + dy, angle);

};

piece.drag(dragmove, dragstart);

// rotation

piece.dblclick(function(e) {

angle += 90;

move(pos.x, pos.y, angle);

});

There’s no need for a dragend function here since the position is updated each time.

The final event handler this function needs is a double click for rotating the piece, and it needs to return something so that all the hard work isn’t lost. I suggest returning the move() function itself in case we need to call it manually after it has returned.

return {

move: move

};

} // close the function

Here it is altogether:

function tile(num_dots_top, num_dots_bottom, x, y, a) {

if (typeof(num_dots_top) === "undefined" || typeof(num_dots_top) ===

"undefined") {

console.log("You must supply values for both sides of the tile.");

return null;

}

// positional info. Defaults

var pos = { x: x || 0, y: y || 0, a: a || 0 },

centroid = { x: pos.x + SPACING * 1.5, y: pos.y + SPACING * 3 };

// Raphael objects

var top = make_face(patterns[num_dots_top]),

bottom = make_face(patterns[num_dots_bottom]),

piece = paper.set([top, bottom]);

// function to place piece at x,y location, rotated to angle a (in degrees)

var move = function(x, y, a) {

pos = {x: x, y: y, a: a};

centroid = { x: pos.x + SPACING * 1.5, y: pos.y + SPACING * 3 };

top.transform("T" + x + "," + y + "R" + a + "," + centroid.x + "," + centroid.y);

y += SPACING * 3;

bottom.transform("T" + x + "," + y + "R" + a + "," + centroid.x + "," + centroid.y);

};

// initial position

move(pos.x, pos.y, pos.a);

// drag variables

var dragx, dragy;

// drag handlers

var dragstart = function(x, y, e) {

dragx = pos.x;

dragy = pos.y;

};

var dragmove = function(dx, dy, x, y, e) {

move(dragx + dx, dragy + dy, angle);

};

piece.drag(dragmove, dragstart);

// rotation

piece.dblclick(function(e) {

angle += 90;

move(pos.x, pos.y, angle);

});

return {

move: move

};

} // close the function

For an actual game, one would presumably want to randomly generate a certain number of tiles. For testing, let’s make a complete set of tiles. To do so, just call the function for every unique combination of numbers using a nested loop. We’ll save references to the tiles in an object. Since there are 28 tiles, four rows of seven seems logical.

var tiles = {};

var count = 0;

for (var c = 0; c <= 6; c += 1) {

for (var i = c; i <= 6; i += 1) {

var t = tile(c, i, 10 + (SPACING * 3 + 10) * (count % 7), 10 + (SPACING * 6 + 10) * Math.floor(count / 7));

tiles[c + "-" + i] = t;

count += 1;

}

}

See this code live on jsFiddle.

Fire this up and you’ll see 28 beautiful tiles. You can drag and rotate them to your heart’s delight.

There is one small improvement I want to make. When objects overlap, the one that was most recently added to the page gets displayed on top; this is known as paint order. When manipulating a particular tile, we would like it to appear above its neighbors. Raphael offers convenient functions called toFront() and toBack() that can move an element or set it above or behind the rest of the elements on the canvas. It’s a matter of taste where we want to attach the function. I’m going to stick it on a mouseover() event so that players can browse tiles by grazing the screen, but if this seems too intrusive, mousedown() is a fine alternative.

This can go anywhere in the tile() function after piece is defined:

piece.mouseover(function(e) {

piece.toFront();

});

It might also occur to you to simply stick the toFront() call in the move() function. While I like the way you think, I don’t love the idea that this method would be called many times a second during a drag. Behind the scenes, Raphael is rearranging the elements in the DOM to get the one you need on top. Let’s not ask it to do so unnecessarily often.

There isn’t space here to code the rules of the game—also, I don’t feel like learning them—but I would submit that doing so would be easy compared to the hard but fruitful work of making the set. You would probably start by adding a dragend() event handler to snap a piece to the nearest open position on the board, then check the adjacent pieces to see if the move is valid. Even adding a secret code for “evil big brother” to scatter the tiles is easily within the realm of possibility, though it would be a lot cooler with animations. That sounds like an excellent topic for a future chapter.

Final Thoughts

Event handlers are the ambassadors of the Web, shuffling between your users and your code. Any web page is fundamentally a collection of things that you present to other people: images, boxes of text, menus, buttons, and, if you’re reading this, shapes and lines.

Raphael allows you to make those things resemble the actual world with far greater verisimilitude, whether it’s dominoes or something larger. (In the next chapter, we’re going to make a baseball field.) It is my experience that things in the real world are not all bolted down—I’m fortunate to have avoided prison—and the methods in this chapter allow you to make those things come alive.