RaphaelJS: Graphics and Visualization on the Web (2014)

Chapter 5. Animations, Part One

At some point in your career as a Raphaelite, you will probably discover that, like the Greek sculptor Pygmalion, you are so enamored with your creation that you wish it could become a living being. Pygmalion had to invoke the help of Venus. We only need to use animations.

We already have plenty of practice changing the properties of our objects, whether it’s altering their color or applying a transformation when the user clicks them. Animations do not introduce any fundamentally new concepts; they merely instruct Raphael to take its time getting from A to B.

The Basics

First, let’s dial up our pal the red dot.

var paper = Raphael(0, 0, 500, 500);

var dot = paper.circle(50, 50, 20).attr({ "fill": "red" });

Next, we’ll instantiate a new animation, which takes two arguments (for now): an object representing a series of properties we would like our element to have at the end of its journey, and the number of milliseconds it should take to reach this state.

var anim = Raphael.animation({ cx: 100, cy: 200, fill: "blue" }, 1000);

Note that dot is not referenced anywhere here. Like functions that can manipulate a wide variety of objects, animations exist independently of elements. We could apply this new animation to anything we like, though it won’t make much sense for elements that do not have a cx or cyproperty.

To connect the two, we feed anim to the .animate() method of our dot:

dot.animate(anim);

See this code live on jsFiddle.

Fire this up and you will see the red dot travel to the coordinates (100,200) and turn blue over the course of one second.

Another thing to note is that animation() is a function attached to the global object Raphael, not a method of the paper instance that we typically declare on the first line of any project. It’s easy to mess this up early in your Raphael journey, before the distinction is clear. Functions that are methods of paper, like .circle() or .path(), return objects that have a physical representative on the page, and thus need to be associated with a specific canvas. Raphael.animation() does not make a new element. It just sets the stage for a manipulate once fed to thepaper.animate() method.

Animation objects like anim have two methods of their own: .delay() and .repeat(). The first takes an input of milliseconds that cause the animation to wait before firing, while the second takes an integer for the number of times the animation should loop. You can call these functions either when declaring an animation:

var paper = Raphael(0, 0, 500, 500);

var square = paper.rect(50, 50, 100, 25).attr({ "fill": "green" });

var anim = Raphael.animation({x: 100, y: 200, height: 125}, 750).delay(1000);

// causes square to sit around for 1 second before animating

square.animate(anim);

…or when feeding it to an element:

var paper = Raphael(0, 0, 500, 500);

var anim = Raphael.animation({x: 100, y: 200, height: 125}, 750);

// causes square to sit around for 1 second before animating

square.animate(anim.repeat(2));

Charmingly, .repeat() even understands a value of Infinity as an input, though the processor on the computer is likely to blow before time ends.

Getting There is Half the Fun

Right now, the shapes that we’re animating move with a constant velocity, i.e., after half the duration we’ve specified, they are halfway there. We’d needn’t be so stiff! Raphael offers a variety of easing formulas that specify different tempos for the animation.

Think of it like driving to the house of a friend who lives 40 miles away. Let’s say you have to be there in exactly an hour, just in time to participate in a surprise party but not so early as to ruin said surprise. The simplest thing to do is set your cruise control to 40 miles an hour. But of course, your residential neighborhood, overpopulated as it is with dogs and children, frowns upon that sort of behavior. More likely, you will go 20 mph for a few minutes, 40 mph for a bit longer, 65 mph on the interstate, and then back to 40 mph after getting off the interstate. You will glide into her driveway at a mild 10 mph, arriving at the exact same time as if you’d gone 40 mph the whole way.

Similarly, easing formulas do not alter the total time it takes an animation to complete, only how much progress it has made at incremental points in between.

To use an easing formula, you feed the animation a string as its third argument. The default easing formulas are linear, easeIn, easeOut, easeInOut, backIn, backOut, elastic, and bounce. Let’s see what a few of them look like.

var paper = Raphael(0, 0, 500, 500);

var dot = paper.circle(50, 50, 20).attr({ "fill": "red" });

// let's make a little more room so as to have time to see the full effect

var anim = Raphael.animation({cx: 200, cy: 300, fill: "blue" }, 1000, "easeIn");

dot.animate(anim);

Here, we see the animation start slowly and then speed up. (Perhaps you overdid it on caution driving the first leg of your trip and have to floor it to get there on time.)

Here’s a fun one:

var paper = Raphael(0, 0, 500, 500);

var dot = paper.circle(50, 50, 20).attr({ "fill": "red" });

// let's make a little more room so as to have time to see the full effect

var anim = Raphael.animation({cx: 200, cy: 300, fill: "blue" }, 1000,

"backOut");

dot.animate(anim);

Here, you missed the exit, went too far, and had to turn around at the end. But you still made it in exactly an hour!

Playing around with the different easing formulas makes for a fun 15 minutes. A little bit later in this chapter, we’ll learn how to make our own.

Being There is the Other Half of the Fun

Adding to the above example, let’s paste a message to the screen celebrating the completion of the animation:

var paper = Raphael(0, 0, 500, 500);

var square = paper.rect(50, 50, 100, 25).attr({ "fill": "red" });

var anim = Raphael.animation({x: 100, y: 200, height: 125}, 1000, "easeIn");

square.animate(anim);

alert("We've arrived!");

Whoops! That doesn’t work at all; the message pops up immediately after the square takes off. This is because of an essential point for animations: life goes on everywhere else on the page while the animation is taking place. And we should be thankful for it, because otherwise it would be impossible to have any sort of concurrent activity on the page, such as two balls bouncing or two characters barrelling toward their confrontation. Imagine how dull Super Mario Brothers would be if Mario and the Goombas took turns moving! Of course, deep inside the machine, everyone is taking turns—we’re not talking about parallel processors here. The effect, however, is of simultaneous movement.

Fortunately, Raphael.animate() accepts a function as a final argument that gets called only after the animation is complete. Let’s try this the right way:

var paper = Raphael(0, 0, 500, 500);

var square = paper.rect(50, 50, 100, 25).attr({ "fill": "red" });

function whenDone() {

alert("We've arrived!");

}

var anim = Raphael.animation({x: 100, y: 200, height: 125}, 1000, "easeIn", whenDone);

square.animate(anim);

See this code live on jsFiddle.

The function whenDone is known as a callback function, a non-technical term for functions that fire at the end of some event, since they call you back when something has finished happening. I never cared for this analogy, but it’s the accepted term. If you’re familiar with retrieving files using AJAX calls, this will look familiar (if not, no sweat). When getting a file from a server, you have to make sure the file comes back before you operate on it, so you attach a callback function to the request. Under the hood it’s totally different, but the syntax is remarkably similar.

Of course, you don’t always need all four arguments. You may want a callback function but be perfectly fine with the default linear easing. You could just write the word easing for the third argument, but that would be kind of a drag. Fortunately, Raphael is actually pretty smart about what you give it. If it gets a function for the third argument, it knows it’s probably the callback function.

Animating Paths

You can animate the path property of a shape just like x, y, or any other property. Raphael has to do a little more work for us here to figure out what to do. Let’s look at an example using our NGon function from the previous chapter.

var paper = Raphael(0, 0, 500, 500);

function NGon(x, y, N, side, angle) {

paper.circle(x, y, 3).attr("fill", "black");

var path = "",

c, temp_x, temp_y, theta;

for (c = 0; c <= N; c += 1) {

theta = c / N * 2 * Math.PI;

temp_x = x + Math.cos(theta) * side;

temp_y = y + Math.sin(theta) * side;

path += (c === 0 ? "M" : "L") + temp_x + "," + temp_y;

}

return path;

}

var pentagon_path = NGon(50, 50, 5, 20);

var decagon_path = NGon(50, 50, 10, 20);

var shape = paper.path(pentagon_path);

var anim = Raphael.animation({ path: decagon }, 1000);

agon.animate(anim);

See this code live on jsFiddle.

There are some good things and some bad things going on here. The good thing is that the shape successfully animates from a five-sided one to a ten-side one over the course of one second, like we asked. The bad thing is that it achieves several advanced yoga poses in the process. This is because, unlike moving something from one point to another, there’s no single obvious way to transform one shape into another—even when it’s a simple as doubling the number of sides in an object. When assigned the task, Raphael first matches the old path and the new path point by point, then tacks on any extra points in the new path to the end.

In a perfect world, Raphael might be able to interpolate a little and add the new points between the existing ones when appropriate. The world being imperfect, we can help it out by packing in the extra points that we’re going to need later.

Let’s practice by making a second function, N2Gon, which doubles up on the points:

var paper = Raphael(0, 0, 500, 500);

function NGon(x, y, N, side, angle) {

//same as above

}

function N2Gon(x, y, N, side, angle) {

var path = "",

c, temp_x, temp_y, theta;

// double up on points by iterating twice, using Math.floor(c/2)

// e.g. 0,0,1,1,2,2

for (c = 0; c <= 2*N; c += 1) {

theta = Math.floor(c / 2) / N * 2 * Math.PI;

temp_x = x + Math.cos(theta) * side;

temp_y = y + Math.sin(theta) * side;

path += (c === 0 ? "M" : "L") + temp_x + "," + temp_y;

}

return path;

}

var pentagon = N2Gon(50, 50, 5, 20);

var decagon = NGon(50, 50, 10, 20);

var agon = paper.path(pentagon);

var anim = Raphael.animation({ path: decagon }, 1000);

agon.animate(anim);

See this code live on jsFiddle.

Much better! That pentagon makes a beautiful transition to a decagon. It works pretty well even if you boost the decagon to a twelve-sided shape (whatever that’s called).

Generally speaking, when animating paths you want the original shape and the new shape to have the same number of points, or as close to it as possible, even if it means packing a few superfluous points in at one end or the other.

Piecewise Animations

After a while, going straight from point A to point B gets tiresome. You might want to bounce a ball off of a brick wall, which requires an abrupt change of direction halfway through the animation.

To do this, we of course need to start with a brick wall. Brick walls do not animate as a matter of policy, but I think we ought to seize this opportunity to practice:

var paper = Raphael(0, 0, 500, 500);

function brickwall(x, y, width, height, bricks) {

var h = height / bricks,

w = width / 3,

props = { fill: "firebrick", stroke: "#CCC" };

for (var b = 0; b < bricks; b += 1) {

// we'll stick these at 0,0 for now and arrange them in a sec

var shortbrick = paper.rect(0, 0, w, h).attr(props);

var longbrick = paper.rect(0, 0, 2 * w, h).attr(props);

// alternate brick patterns

if (b % 2) {

shortbrick.transform("T" + x + "," + (y + b * h));

longbrick.transform("T" + (x + w) + "," + (y + b * h));

} else {

longbrick.transform("T" + x + "," + (y + b * h));

shortbrick.transform("T" + (x + 2 * w) + "," + (y + b * h));

}

}

}

brickwall(300, 20, 40, 300, 30);

The idea is to have the ball bounce off the wall. So we have to animate it two times, once to get to the wall, once to get away from it.

var ball = paper.circle(50, 50, 10).attr("fill", "orange");

//send it to x coord 290 (the wall is at 300, the radius of the ball is 10)

var animToWall = Raphael.animation({ cx: 290, cy: 150 }, 500);

var animAwayFromWall = Raphael.animation({ cx: 50, cy: 250 }, 500);

We learned the hard way a few pages back that you can’t just do this:

ball.animate(animToWall);

ball.animate(animAwayFromWall);

Raphael doesn’t wait for one animation to finish before firing off the next, so this won’t work. But we can make use of callback functions to fix that:

var animAwayFromWall = Raphael.animation({ cx: 50, cy: 250 }, 1000);

var animToWall = Raphael.animation({ cx: 292, cy: 150 }, 1000, function() {

this.animate(animAwayFromWall);

});

ball.animate(animToWall);

Once again, that’s much better. But we can imagine it getting tiresome if we have more than one brick wall in there. Fortunately, there is a rather poorly documented feature of Raphael that allows us to pack several stages into one animation. You can accomplish the same thing like this:

var anim = Raphael.animation({

"50%": { cx: 292, cy: 150 },

"100%": { cx: 50, cy: 250 }

}, 2000);

ball.animate(anim);

See this code live on jsFiddle.

The percentages refer to the progress through the animation and indicate at which point it switches over from one animation to the next. If you’d like the ball to lose a little velocity on impact, just change the first value to 40% so that it gets there faster.

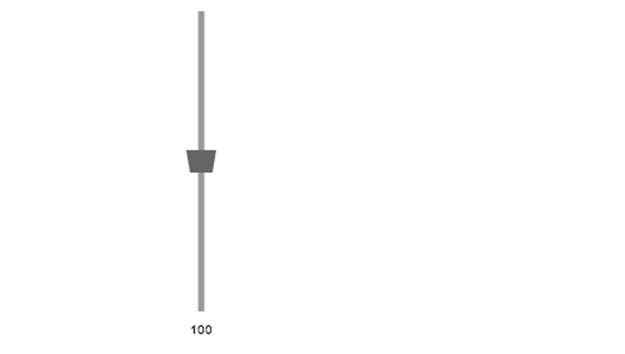

Case Study: Metronome

For many of us, an old-school mechanical metronome evokes cherished memories of practicing scales on the piano, usually at gunpoint. In those pre-Raphaelite days, metronomes were made of metal and wound by hand. The tempo was controlled by an adjustable weight along the arm of the metronome (this is known as an inverted pendulum).

For the sake of nostalgia, and armed with the power of animations, I propose we make a metronome of our own. Like the dominoes example, we’re going to make an object to contain the Raphael elements and return methods to control it.

Since I’m not exactly sure what specifications I’ll need, I’m going to pass only one argument to the metronome function, called opts. This is an object that will contain properties like height and position. This has the advantage of not requiring us to remember the order of the arguments in the function.

var metronome = function(opts) {

// if no options specified, make an empty object

opts = opts || {};

//default values for variables if unspecified

var len = opts.len || 200, // length of metronome arm

angle = opts.angle || 20, //max angle from upright

width = len * Math.cos(angle),

x = opts.x || 0,

y = opts.y || 0,

tempo = 100;

// pieces of the metronome

var arm = paper.path("M" + (x + width) + "," + y + "v" + len).attr({

'stroke-width': 5,

stroke: "#999"

});

var weight = paper.path("M" + (x+width) + "," + (y+len) + "h9l3,-18h-24l3,18h12")

.attr({

'stroke-width': 0,

fill: '#666'

});

/* Next, let's set the weight at the center of the arm, make a label for the tempo, and use a drag event to allow the user to adjust the tempo by moving it. */

//start the weight at the halfway point (18px less than length bc of weight)

weight.position = (len - 18) / 2;

weight.transform("T0,-" + weight.position);

var label = paper.text(x + width, y + len + 15, tempo);

// track drag position

var drag_position;

weight.drag(

function(x, y, dx, dy, e) {

// restrict weight to top of bar and very bottom, allowing for 18px

// height of weight

drag_position = Math.min(len - 18, Math.max(0, this.position - y));

// calculate tempo based on position, with range of 20 to 180 bpm

tempo = Math.round(20 + 160 * drag_position / (len - 18));

label.attr("text", tempo);

this.transform('T0,-' + drag_position);

},

function(x, y, e) {

this.attr("fill", "#99F");

},

function(e) {

this.position = drag_position;

this.attr("fill", "#666");

}

);

}

If the use of drag_position is confusing here, consult Better Dragging.

Let’s see how it looks so far:

var paper = Raphael(0, 0, 500, 500);

metronome({

x: 125,

y: 20,

len: 240

});

Slide that weight up and down and you’ll see the tempo adjust accordingly. Now we need to make it play. To do so, we’re going to return a function called play to set off the metronome. This will go at the end of the function.

Inside the play function, we’re going to be animating the transform property, which means we’ll need two animations: one for the arm and one for the weight, since their transformations are different. They will be three-part animations: a half tick to the right, a full tick to the left, and a half tick back to center. Thus, a full animation represents two ticks of the metronome: Once there, once back.

return {

play: function(repeats) {

var armAnim = {

"25%": { transform:"R" + angle + " " + (x+width) + "," + (y+len), easing: "sinoid" },

"75%": { transform:"R-" + angle + " " + (x+width) + "," + (y+len), easing: "sinoid" },

"100%": { transform:"R0 " + (x + width) + "," + (y + len), easing: "sinoid" }

};

var weightAnim = {

"25%": { transform:"T0,-" + weight.position + "R" + angle + " "

+ (x + width) + "," + (y + len), easing: "sinoid" },

"75%": { transform:"T0,-" + weight.position + "R-" + angle + " "

+ (x + width) + "," + (y + len), easing: "sinoid" },

"100%": { transform:"T0,-" + weight.position + "R0 "

+ (x + width) + "," + (y + len), easing: "sinoid" }

};

//2 iterations per animation * 60000 ms per minute / tempo

var interval = 120000 / tempo;

arm.animate(Raphael.animation(armAnim, interval).repeat

(repeats / 2));

weight.animate(Raphael.animation(weightAnim, interval).

repeat(repeats / 2));

}

};

Last, let’s add a button in the HTML to trigger the metronome. Make sure to give the container div a little height so that it doesn’t cover up the button.

<input type="button" value="play" id="play" />

<div id="canvas"></div>

And we’re all set:

var paper = Raphael("canvas", 500, 500);

function metronome { /* all of the above */ }

var m = metronome({

x: 125,

y: 10,

angle: 30,

len: 240

});

document.getElementById("play").onclick = function() {

m.play(10);

}

Each time you click the play button, you’ll get 10 ticks of the metronome at the tempo specified by dragging the weight.

See this code live on jsFiddle.

Wait, Aren’t You Forgeting Something?

Oh right, sound! Getting audio in a browser is a bit outside the scope of this book, though it’s not too difficult (particularly if you decide only to support browsers that recognize the audio tag).

To add to this feature, you’d add the function to make the ticking a callback property in armAnim, like so:

var armAnim = {

"25%": { transform:"R" + angle + " " + (x+width) + "," + (y+len), easing: "sinoid", callback: function() { console.log("tick"); }},

"75%": { transform:"R-" + angle + " " + (x+width) + "," + (y+len), easing: "sinoid", callback: function() { console.log("tock"); }},

"100%": { transform:"R0 " + (x + width) + "," + (y + len), easing: "sinoid" }

};

Final Thoughts

Playing with animations is great fun in Raphael because it does so much of the work for you. Just specify the before and after photos and let the code worry about shedding all those pounds.

I probably wouldn’t use Raphael for a feature-length animated movie, but I would—and do—use its animations to breathe a little life into an otherwise static-looking website. Even the five-page website I made for my wedding uses Raphael to write my name and that of my lovely fiancée in script across the screen, as though an invisible hand were practicing its (flawless) cursive. A little movement signals to viewers that this is not just another assemblage of JPGs. And when it responds to their mouse movement, as we now know how to do, they’ll also realize it is not even another assemblage of GIFs.