Scenario-Focused Engineering (2014)

Part I: Overview

CHAPTER 1 Why delight matters

CHAPTER 2 End-to-end experiences, not features

CHAPTER 3 Take an experimental approach

Chapter 1. Why delight matters

Why does delight matter? For many human reasons, of course: the need for joy, as an antidote for loneliness or boredom, as a prompt for action or contemplation. And for software engineers, delight is also at play in their relationship with their customers. This chapter makes the case that satisfying customers with a solid, useful, usable product is no longer good enough. To compete effectively in today’s marketplace, you have to take your work to the next level and delight your customers on an emotional level.

A car story

On my drive to work today, I looked in the rearview mirror and saw a smile on my face. Just a hint of a smile; it reminded me a bit of the Mona Lisa. You know the look: a little bit coy, implying that “I know something you don’t know.”

I realized that I was smiling simply because I was enjoying the experience of driving to work in a new car. Don’t get me wrong—this wasn’t a life-transforming experience, but I was really enjoying my commute, which is a little strange, isn’t it? And quite honestly, I knew that when I got to work that little smile was going to evolve into a boasting session at the coffee machine. The first few colleagues I ran into were going to hear about how much I love that new car:

“I bought a new car last week. I just love it. It’s awesome. You know, I traded in my sports car to get this—did I tell you that already?”

“No way—you got rid of that?! That was a sweet car. What possessed you?”

“I know, it’s crazy. But this new car is so awesome. I’m really happy I made the trade.”

I wanted to share my joy with others. I wanted to tell people about this great car I had discovered because I thought they might like it, too. But why? What was it about that car that made me love it so much? What made it call to me as I passed by it in my garage? Why did I feel compelled to tell others about it?

The car has a set of features that are on par with most other cars in the same price range and category. It has satellite radio, automatic this ‘n’ that, and a sunroof, but so do lots of cars. It’s not the features. I’ve purchased cars and other products with lots of features before, but those products don’t necessarily end up being the ones that I love. It’s got to be more than just the feature list.

So what is it that makes this particular car so endearing to me?

More data about me

Here’s the story of what was going on in my life at the time. Maybe it will give some insight into why this car is so special to me.

Recently, I traveled to Europe with my children for our summer vacation. In lieu of the fantastic rail system, we chose to rent a car and drive around France, Germany, and Austria. The car I rented was quite small, at least by American standards. It maneuvered well along the narrow cobblestone streets, but it also held its own on the autobahn. It was extremely fuel-efficient. And as with one of those cartoon clown cars, somehow we were able to fit all our luggage in the trunk of this little car, with plenty of room in the passenger area. It defied physics, I don’t know how.

So I learned to love this little car as we traveled throughout Europe. It was the perfect travel experience for our family. Toward the end of the trip I started doing some research to see whether I could purchase one back in the US. You see, back home I had been questioning my personal car strategy. I very much wanted to find a car (or cars) that would meet all of my needs. Every solution I drew up, every combination of cars I could imagine, forced compromises on me that I wasn’t willing to make.

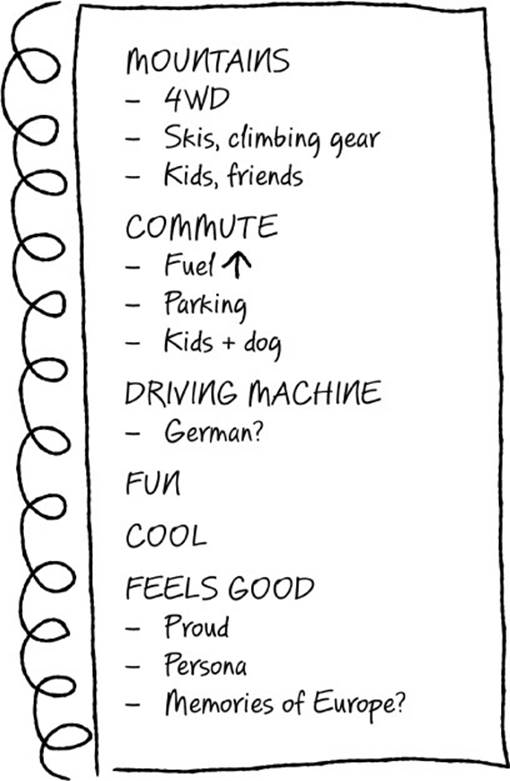

My criteria

When I returned home, I spent a remarkable amount of time on the Internet continuing my research about cars. I thought it would be easy, but the right car solution proved to be elusive. I decided to do some deep thinking and put together a list of my criteria. Surely, once I did that, the answer would become apparent.

I have two teenage children. Often, I need to cart them around, plus their friends and all their gear. My hobbies and passions often take me into the local mountains, which are quite rugged. Plus, I needed something fun—wind in the hair, midlife crisis kind of fun. I had a strong “I’ll know it when I see it” feeling about the car, but I had a very difficult time communicating exactly what that was.

My current car setup included a convertible sports car (two-seater) and a large American four-wheel-drive truck. But this arrangement wasn’t satisfying my needs. Both the kids can’t fit in the sports car. The truck is a big gas-guzzler that can’t fit into parking spots in the city and is just too expensive to use for commuting and soccer-mom duty. Morally, I’m opposed to owning three cars. Here’s what my criteria looked like.

I was delighted with that little car in Europe. Between that and my truck, I knew all my needs would be met. But I quickly discovered that the car we had in Europe isn’t sold in the US. And I couldn’t find an equivalent.

This is a lot of detail, but I want to communicate how much having the wrong set of cars in my garage was bugging me. I had a taste of a great experience in Europe, but that solution wasn’t available. Nothing available met my criteria. I was frustrated, and every time I got into one of my cars, I was reminded of my frustration.

The experience

Finally, I found my car.1 I discovered a small, German-engineered hatchback. It could fit five people comfortably along with a bunch of gear. Its turbo-diesel engine gets up to 50 miles per gallon on the highway. The combination of this car, along with my truck, meets all of my criteria.

But this doesn’t explain why I have an emotional connection with this car. Look at the words I listed on the bottom of my notes: fun, cool, feels good, proud, persona. Those words describe the experience I get when I drive this car. It’s not all the features (50 MPG, room for my kids). And while the experience I had at the dealership was indeed a good one, it played a minor role (this time anyway) in my overall delight with this car.

You see, it’s not just the car. It’s all the stuff the car does that suits me perfectly. I feel as though whoever built that machine knew me, that they figured out what I needed and put it all together in a way that resonates deeply within me. And it’s that positive end-to-end experience I continue to have—from discovering the car, to an easy and friendly purchase experience, to driving it off the lot, to getting my first free car wash (yeah, the car came with free car washes—for life!). No wonder I tell people about this experience—it’s been awesome.

What do you recommend?

So the big question is . . . what about you? What is your “I have to tell you about this great car I found” story? Have you ever discovered yourself sounding like an unpaid sales rep for some product or service? I’m sure you have. Think about it. What was the last product you recommended to a friend just because you loved it so much and you wanted to tell someone about it?

When we teach our Scenario-Focused Engineering workshops, we start by asking people this very question:

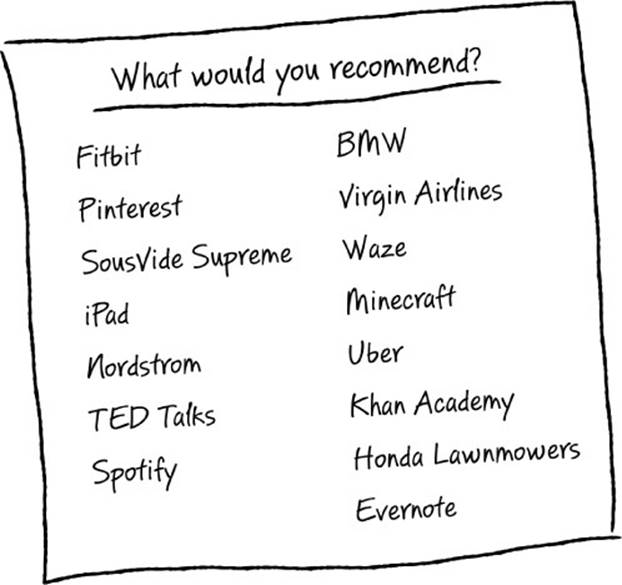

What product or service do you love so much that you would unabashedly recommend it to your friends and colleagues? Discuss with your table group.

The “What Product Do You Recommend to Others” exercise has been fascinating in several regards. First, it’s typical that once the conversations begin, the room becomes quite noisy. It may take a few minutes for the ruckus to start, as some engineers are a bit introverted and not prone to spilling their emotional guts. But once a few people start talking about their favorite products, others start talking about theirs. People become excited and start speaking louder because they want to be heard and they really want to tell their stories about what they’ve discovered, what they love, and why. You would be amazed at how animated and boisterous these conversations become.

The level of engagement in this conversation is noteworthy, but it’s also fascinating to see the lists of products these teams come up with. Here’s a list of products that a class came up with during a recent recommendation exercise. At the time the list was created, these products and services resonated so well with the workshop participants that they were mentioned not just in the small discussion groups, but people felt compelled to brag about them to the whole room.

The world moves quickly, so by the time this book is published, we’re sure the list would be different. Your personal list will contain different products as well, of course. So think about it. Spend just a couple of minutes and think about what products or services you would recommend to a friend.

The common thread

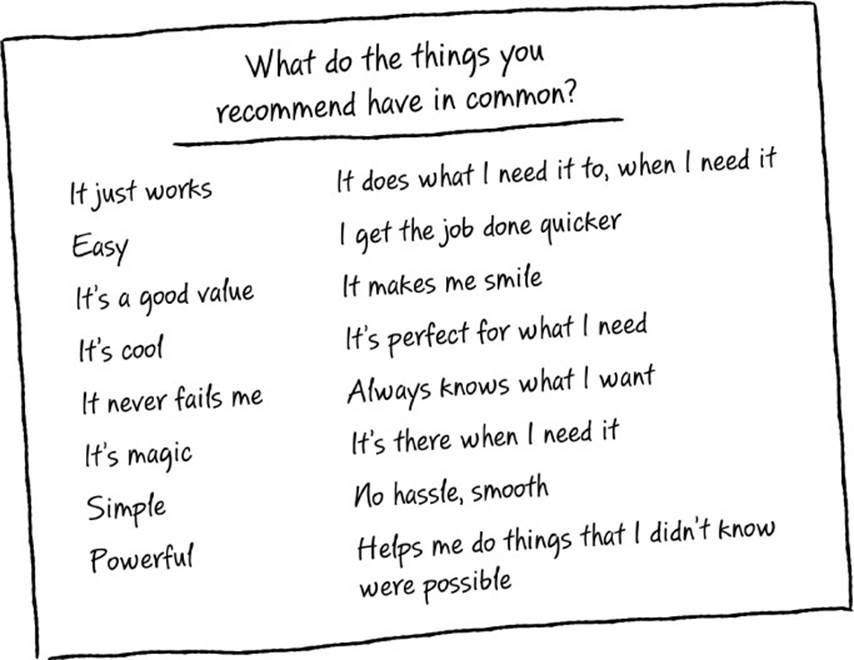

Even though we know the products on this list change over time, the interesting question to explore next is “What are the qualities that these products or services all have in common?”

We ask this question as an exercise early on in the workshop, and it’s not an easy question to answer. The list that any given class creates usually covers a wide variety of consumer products, automobiles, devices, and services as well as productivity applications, developer tools, and even favorite vacation spots. The common factor on these lists is not the market or demographic, nor is it the price point or set of features. What is it then that links these seemingly disparate items?

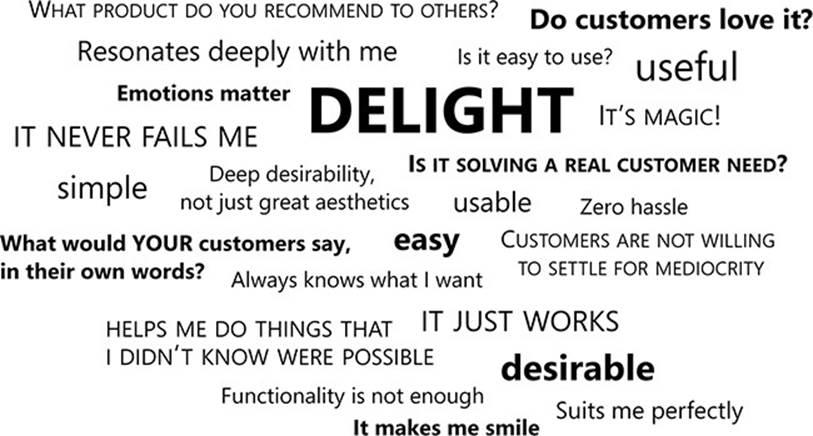

Here are the phrases that come up when participants describe these products:

The set of answers does not change every six months. It is remarkably consistent. Despite the fact that the list of recommendations changes over time, the characteristics of those products and services are fairly static.

Talking about cool things you love can be a lot of fun. Next time you’re in an appropriate social situation, go ahead and start the conversation. Ask people what products and services they’re using today that they love. Think hard about the qualities of those products and ask yourself why do people mention those and not others?

The reality check

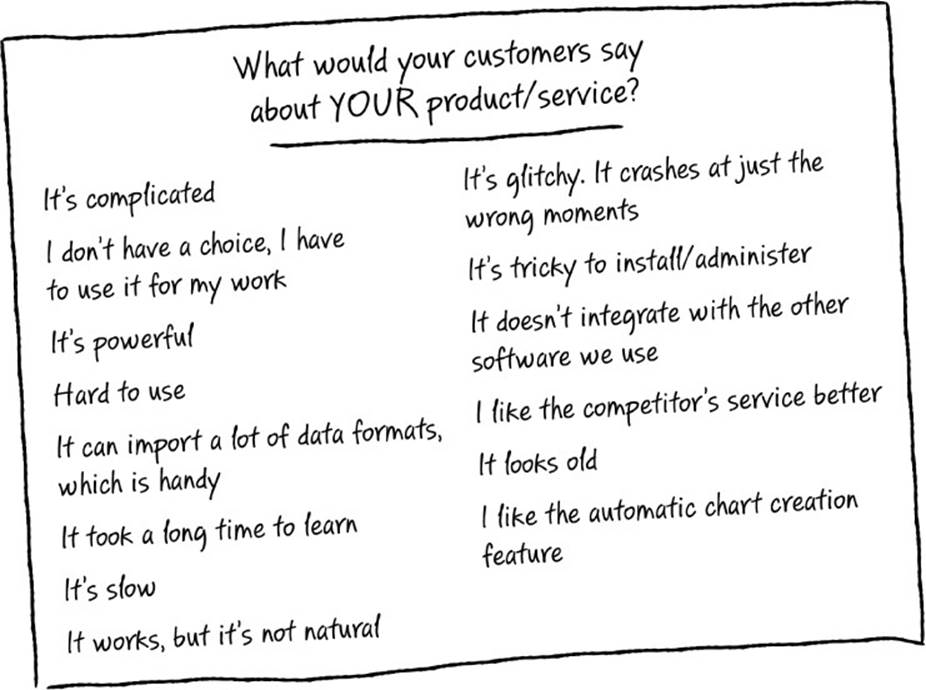

The final questions we ask in this exercise involve a reality check: What do your customers say about the products and services you provide? What would they say, in their own words? We ask the class to think about these questions as well. The next illustration shows some common answers.

Of course, every product has its bright spots. If it didn’t, chances are that the team or company that produced it wouldn’t be around anymore to talk about it. But when asked, most teams realize that their products and services are not eliciting the strong, positive emotional connection they strive for. They are not truly delighting their customers. And though this realization usually isn’t a complete surprise to most engineering teams, most teams have a tough time figuring out how to go about solving that problem. Setting a goal or directive to “go build something that will delight our customers” does not lend itself to an actionable list of problems to solve.

While reading this book, if you ever need some motivation to do a better job for your customers, consider what your customers would say about your current offering, and challenge yourself to see whether you can do better. Can you build something your customers will truly love, so much so that they would go out of their way to recommend it to a friend?

Useful, usable, and desirable

The computer industry has matured quite a bit over the past few decades, and these days customers are demanding an ever-higher degree of sophistication, personalization, and polish. Customers are much more savvy and have had a taste of what truly outstanding solutions look like. Customers today are generally not willing to settle for mediocrity.

Useful

However, it wasn’t always this way. At the beginning of the personal computing era, it was enough for new products simply to be useful—to solve a problem in a way that had never been done before. This was the era of the Commodore 64, the IBM Personal Computer, MS-DOS, VisiCalc, and the like. I have fond memories of manually typing in programs, line by line, from the back of Games magazine—and the all-important checksum in the right-hand column to prevent those insidious typos. Who were the predominant customers then? Like me, they were mostly computer geeks themselves, or geek wannabes—technology-savvy early adopters willing to put up with a sometimes steep learning curve and motivated to get the most out of this new technology, whether for work or play.

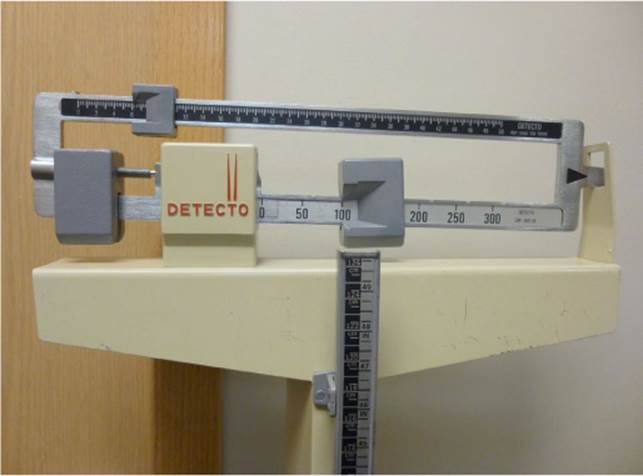

Consider this analogy: a traditional scale in a doctor’s office is a useful and highly accurate tool, but you have to know how to work it—where to move the weights, how to read the result. In this case, the utility provided is well worth the training burden because the same person uses the scale over and over every day. But most average people aren’t quite sure exactly how to work it—they could figure it out, but it isn’t completely obvious.

Usable

Then, in the mid-1990s, the computing market had a significant transformation. Windows 95 and Office 95 were released with new graphical user interfaces, Apple was gaining ground with the Power Mac, and the Internet was quickly becoming mainstream. Around this time it became important for products to be not just useful but usable, and most software companies began investing in usability testing to optimize their products for ease of use, efficiency, and especially discoverability for first-time usage situations. Technology had become simple and accessible enough to open up two major new customer bases: home users, who started buying personal computers for the living room, and the newly minted “knowledge workers,” who started using productivity software—WYSIWYG2 word processors such as Microsoft Word and spreadsheets such as Lotus 1-2-3.

Go back to our scale analogy: What would a more usable scale look like? Chances are you have one in your bathroom right now. This scale is dead simple to operate—just step on the scale and look down to read the number. No instruction booklet is needed.

Desirable

Over the past decade, we’ve seen the market change yet again. With the advent of mobile devices, tablet computers, connected gaming consoles, and ultraportable (and ultra-affordable) laptops, the customer base has broadened to include the far right end of the adoption curve, pulling in the vast majority of late adopters. As of 2011, fully 91 percent of American adults owned a computer, cell phone, MP3 player, game console, or tablet, and the majority of those who didn’t own any of these devices are over the age of 66.3

While average customers are now less savvy about the inner workings of their computer, they are absolutely addicted to modern technology. With groundbreaking products now firmly established in people’s minds, such as Apple’s iPhone, Microsoft’s Kinect, Facebook, Salesforce.com, and Ruby on Rails, customers in all demographics have gotten a good taste of what truly outstanding solutions look like, and they don’t want to go back. These days, customers not only expect drop-dead simplicity, they also expect deep personalization—for solutions to magically anticipate their needs, and for their technology to follow them wherever they go. In short, they expect a smooth, seamless end-to-end experience.

Also relevant is the trend toward the consumerization of IT. IT departments are now bending once-sacred deployment and security rules because employees say they can’t live without certain consumer products at the workplace, including iPhones, iPads, or Galaxy tablets. The pull of desirable computing solutions that is already highly visible in consumer behavior is now reaching work-oriented markets as well. Providing compelling end-to-end experiences is rapidly overtaking every corner of the market: consumer, developer, enterprise, and small business.

As we’ve already mentioned, truly outstanding solutions have some things in common. Great products go far beyond simplistic first-time usability. They stitch together functionality into end-to-end experiences that deeply resonate with customers. Tasks that used to require multiple applications and manual steps can now be performed in a simple, coordinated one-stop shop: sharing photos with friends on Facebook, fully integrated team-based development environments, collaborating on documents in the cloud with seamless access anywhere. The overall quality of offerings is better, with consistent reliability, availability, and polish. These great products feel as though they have a soul—a real purpose, mission, and personality—not just an impersonal collection of computational tools. When you have all these ingredients, the best of the best have an emergent quality—they evoke an emotional response from their users, just as I showed in the car story.

To stand out in today’s market, products need to be genuinely desirable. However desirability isn’t necessarily about flashy graphics or polished surfaces. We’re talking about deep desirability, a quality that makes a product so good, so perfect, so “just right for me” that it evokes an emotional connection. Great aesthetics can certainly help, but the core of the solution is its desirability.

A desirable scale?

So getting back to our scale example, what would a deeply desirable scale look like? This is a bit tougher to answer. You see, the question you really need to ask is “Why do you want a scale in the first place?” Is it because you actually want to know the number: How much you weigh? Or is it because you are hoping that the number will change? Why do you want the number to change? Are you going on vacation soon and want to look good in a bathing suit? Have you just signed up for your first triathlon and the number is part of a fitness calibration? Just making the scale more visually beautiful won’t address any of those needs. Here’s another motivation, or scenario, for your use of a scale: Perhaps what you really want is a scale that lies, that tells you it’s okay to eat that bacon cheeseburger? Or maybe what you really desire is something like this—the Nintendo Wii Balance Board, companion to the Nintendo Wii Fit.

Somewhat surprisingly, this was one of the best-selling console game peripherals for its time.4 Nintendo was the first to capitalize on the fact that an awful lot of people are unhappy with their weight. Since then, the same insight has inspired the Fitbit, the Nike FuelBand, and many Microsoft Kinect titles. These companies built products that resonated with a deep-seated human vulnerability, giving customers new hope that they could finally get control of their body weight. Sure, the Nintendo Balance Board is a scale (it’s actually two scales, one for each foot), and it will tell you your weight and even graph it over time. But more importantly, when combined with the Wii Fit software, it’s part of an engaging exercise program that gets you up off the couch to start changing that number. The clean white color and high-quality industrial design of the Balance Board isn’t why it sold so well. Rather, the end-to-end experience of the Wii Fit plus the Balance Board struck a chord—an emotional chord deep inside—about insecurity versus confidence, apathy versus motivation, weight versus beauty. It gave people hope that finally achieving the body shape they were longing for could be fun and easy. Again, deep desirability goes way beyond surface aesthetics.

Putting it together

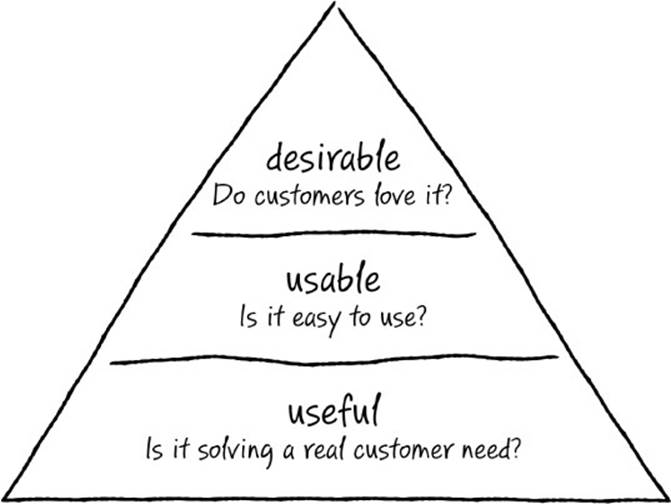

Putting it all together, you get a pyramid (like the one shown on the next page) that rests on useful at the base, has usable as the middle tier, and desirable at the pinnacle. This useful-usable-desirable model was devised by Dr. Elizabeth Sanders in 1992,5 and there have been many variations since. But the original terms and ideas are just as valid now as they were then.

It’s essential to start by solving a real customer problem. Solving a problem that no one cares about is the first, most painful mistake to make, and no amount of great usability or flashy paint jobs will save you from that.

Next, your solution needs to be usable. It needs to be easy to use, smooth, and seamless. No hassles, no hoops to jump through, ideally no need for documentation or help. It just does exactly what the customer expects at every step along the way.

Finally, your solution needs to be desirable. The customer needs to love it. What that love looks like may be different for different kinds of solutions and different types of customers, but to really hit it out of the park, you need to evoke that strong, positive emotional connection.

![]() Mindshift

Mindshift

What is delight, exactly? Occasionally, the words “desirable” or “delight” or “love” provoke some controversy. When we say that products and services should delight customers, or that customers should love your solutions, what exactly do we mean? Are we saying that for absolutely everything that you build, customers need to be head over heels about it and think that it’s the best thing that has ever been invented? Does there need to be an element of surprise or serendipity for it to count as delight? Should customers always have that warm, fuzzy feeling inside when they think about your solutions? No, not exactly.

While certainly you hope that some solutions will evoke those warm fuzzies in your customers, that’s a much narrower definition of delight or desirability than we intend. The English language doesn’t help here because there isn’t an ideal word for the concept we mean. Delight and desirability come the closest, but they are imperfect.

When we say that a solution is delightful or desirable for a customer, what we mean is that it evokes some kind of nontrivial positive emotion. Sometimes that positive emotion will be a sense of satisfaction with getting a tough job done more easily than expected. Sometimes it will be relief at not looking stupid in front of an important colleague. Other times the feeling may be joy at being able to see a granddaughter’s smiling face, and occasionally it may be a sense of wonder at an experience that truly seems magical. The important point is that customers have some kind of meaningful, positive emotional response about the software, not just a fleeting “That was cool” that is forgotten as quickly as it came. And this kind of deep, lasting delight simply cannot happen if you aren’t first solving a real problem for a customer in a useful and usable way.

For the rest of this book, we use delight and desirability to refer to this idea, and we trust that you’ll know what we mean.

The natural next questions are “How do you achieve desirability?” and “What’s the formula for customer delight?”

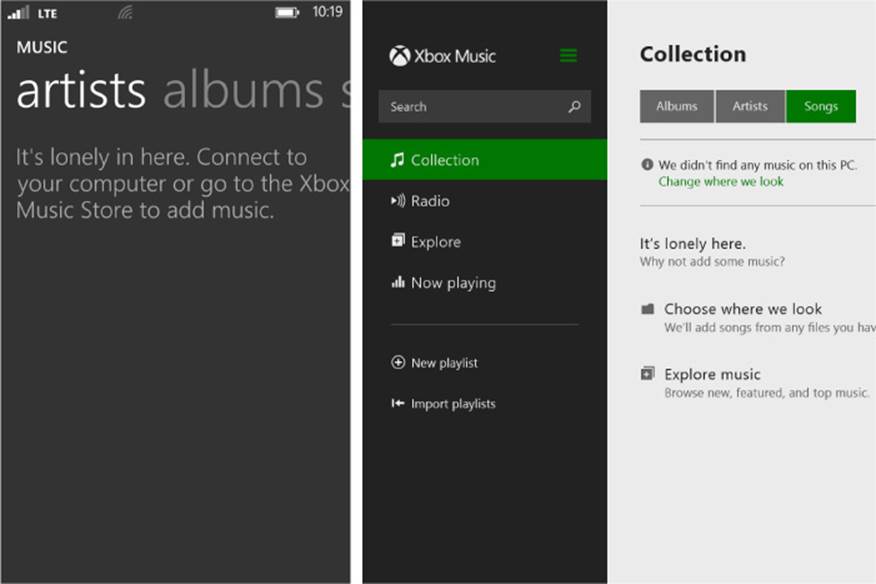

Of course, there are some tricks and tips you can try. For instance, it’s relatively easy to see how using more evocative language might make a customer smile, as in these screenshots of an empty music library on Windows Phone and Windows 8.1

Using clever language and a friendly tone is one easy way to create a moment of surprise or serendipity. The right words can make the technology feel more human and more approachable. This is a great technique to use, but keep in mind that it produces customer delight primarily on a surface level. No one purchases a product on the basis of how welcoming the error messages are if the solution itself doesn’t get the customer’s job done. Similarly, beautiful aesthetics don’t matter if the solution underneath is incomplete. Tone, language, and aesthetics all are good ways to polish a great offering, but they are not enough on their own.

Underneath it all, this music library is powered by OneDrive, which does have an incredibly compelling value proposition that is grounded in being genuinely useful—giving you access to all your music, videos, photos, and other files from any computer or mobile device, and even directly within Microsoft Office, is super valuable. Add to that the solid technical execution that makes the solution robust, an experience that works smoothly and seamlessly across all those different platforms, and a well-laid-out, easy-to-use interface, and you’ve got great usability as well. But the real delight of OneDrive is pulling these qualities together in one great package, and above all else, making sure that customers are never ever left in a lurch without access to their files, even if they don’t happen to have Internet access at the moment. When you get to this point, the use of evocative language is a great finishing touch, the cherry on top of an already-delicious ice cream sundae—and the customer can’t help but smile.

The next chapter discusses the most important factor you can plan for to build desirable solutions: solving an entire end-to-end problem and delivering that as a polished, high-quality, seamless experience.

Need more proof?

Think this doesn’t apply to you and your business? Consider this data point from Bain & Company’s research:

Most companies assume they’re consistently giving customers what they want. Usually, they’re kidding themselves. When we recently surveyed 362 firms, we found that 80% believed they delivered a “superior experience” to their customers. But when we then asked customers about their own perceptions, we heard a very different story. They said that only 8% of companies were really delivering.6

This statistic is particularly notable when you consider that Bain also reported that “more than 95% of management teams we’ve surveyed claim to be customer focused.” It seems that industry-wide, hearts are in the right place, but it’s just not as easy as it looks to delight customers.

The good news is that your company is likely not the only one still learning. Forrester Research has been studying customer experience since 1998, and it also concludes that even today “mediocre customer experience is the norm, and that great customer experience is rare. What this means is that customer experience is a powerful differentiator for the very few companies that do it well.”7 So, there is still plenty of upside left for companies that are ready to make the investment in figuring out how to truly delight their customers.

What’s even better is that Forrester has done the hard work to prove it. Every year since 2007, Forrester has conducted surveys asking customers to rate their experience with 160 top North American brands across 13 industries. From the results of those surveys, Forrester created a customer experience index for each brand. The punch line: in 2012, only 3 percent of companies they asked about were ranked “excellent” by customers, and 34 percent ranked “good.” The rest of the companies ranked somewhere between “okay,” “poor,” and “very poor.”

And lest you think those numbers are meaningless, Jon Picoult at Watermark Consulting took it to the next level to show how delivering a great customer experience correlates to financial results. Watermark used Forrester’s index scores to investigate whether delivering a great customer experience could predict stock market performance. Boy, did it ever. His analysis showed that the five-year stock performance of the top 10 companies in the customer experience index for the years 2007 to 2011 had a net gain of 22.5 percent, whereas the laggards in the bottom 10 lost 46.3 percent. The S&P 500 Index dropped 1.3 percent over the same period.8

Harley Manning and Kerry Bodine summarize it best:

For decades, companies have been paying lip service to the idea of delighting customers while simultaneously disappointing them. That approach won’t cut it anymore. Recent market shifts have brought us into a new era, one Forrester calls the age of the customer—a time when focus on the customer matters more than any other strategic imperative.9

Summary

What does this mean for you? Competition is fierce, and the bar is high. To be successful in today’s market you have to figure out how to achieve deep desirability within your customers. Customers now expect products to solve their problems completely and to do it in a delightful way, and this is becoming increasingly true across the industry, not just in consumer products. The goal is a product or service that customers would go out of their way to recommend to a friend.

The old technique of prioritizing a bunch of features and building as many as your schedule allows (in priority order, of course) just doesn’t cut it anymore. Usability testing is still a great technique in the toolbox, mind you, but it’s nowhere near sufficient on its own to compete in today’s market. You need some new tools in your tool belt, and perhaps even more importantly, an adjustment in your philosophy of what software development is all about. This book will introduce you to an iterative, customer-focused approach to engineering that will dramatically increase your odds of creating products that will deeply delight your customers.

Notes

1. I am intentionally not revealing the make and model of the car. When I tell this story, people always ask what car I bought, but I find that the answer is largely irrelevant. The important part of this story is to recognize that there is an end-to-end experience and that the experience can evoke emotions (both positive and negative) in the user of a product.

2. WYSIWYG stands for “What you see is what you get.”

3. Amy Gahran, “90% of Americans Own a Computerized Gadget,” CNN Tech, February 3, 2011, http://www.cnn.com/2011/TECH/mobile/02/03/texting.photos.gahran/index.html.

4. “Nintendo Announces the Wii Balance Board Has Sold Over 32 Million Units Worldwide, Becomes a World Record,” accessed August 27, 2014, http://www.qtegamers.com/2012/01/nintendo-announce-wii-balance-board-has.html.

5. Elizabeth B.-N. Sanders, “Converging Perspectives: Product Development Research for the 1990s,” Design Management Journal 3, no. 4 (Fall 1992): 49-54, http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1948-7169.1992.tb00604.x/abstract.

6. James Allen et al. “Closing the Delivery Gap: How to Achieve True Customer-Led Growth” (Bain & Company, 2005), http://www.bain.com/bainweb/pdfs/cms/hotTopics/closingdeliverygap.pdf.

7. Harley Manning and Kerry Bodine, Outside In: The Power of Putting Customers at the Center of Your Business (New York: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2012), 26.

8. Manning and Bodine, 204-6.

9. Manning and Bodine, 15.

All materials on the site are licensed Creative Commons Attribution-Sharealike 3.0 Unported CC BY-SA 3.0 & GNU Free Documentation License (GFDL)

If you are the copyright holder of any material contained on our site and intend to remove it, please contact our site administrator for approval.

© 2016-2026 All site design rights belong to S.Y.A.