The Go Programming Language (2016)

6. Methods

Since the early 1990s, object-oriented programming (OOP) has been the dominant programming paradigm in industry and education, and nearly all widely used languages developed since then have included support for it. Go is no exception.

Although there is no universally accepted definition of object-oriented programming, for our purposes, an object is simply a value or variable that has methods, and a method is a function associated with a particular type. An object-oriented program is one that uses methods to express the properties and operations of each data structure so that clients need not access the object’s representation directly.

In earlier chapters, we have made regular use of methods from the standard library, like the Seconds method of type time.Duration:

const day = 24 * time.Hour

fmt.Println(day.Seconds()) // "86400"

and we defined a method of our own in Section 2.5, a String method for the Celsius type:

func (c Celsius) String() string { return fmt.Sprintf("%g°C", c) }

In this chapter, the first of two on object-oriented programming, we’ll show how to define and use methods effectively. We’ll also cover two key principles of object-oriented programming, encapsulation and composition.

6.1 Method Declarations

A method is declared with a variant of the ordinary function declaration in which an extra parameter appears before the function name. The parameter attaches the function to the type of that parameter.

Let’s write our first method in a simple package for plane geometry:

gopl.io/ch6/geometry

package geometry

import "math"

type Point struct{ X, Y float64 }

// traditional function

func Distance(p, q Point) float64 {

return math.Hypot(q.X-p.X, q.Y-p.Y)

}

// same thing, but as a method of the Point type

func (p Point) Distance(q Point) float64 {

return math.Hypot(q.X-p.X, q.Y-p.Y)

}

The extra parameter p is called the method’s receiver, a legacy from early object-oriented languages that described calling a method as “sending a message to an object.”

In Go, we don’t use a special name like this or self for the receiver; we choose receiver names just as we would for any other parameter. Since the receiver name will be frequently used, it’s a good idea to choose something short and to be consistent across methods. A common choice is the first letter of the type name, like p for Point.

In a method call, the receiver argument appears before the method name. This parallels the declaration, in which the receiver parameter appears before the method name.

p := Point{1, 2}

q := Point{4, 6}

fmt.Println(Distance(p, q)) // "5", function call

fmt.Println(p.Distance(q)) // "5", method call

There’s no conflict between the two declarations of functions called Distance above. The first declares a package-level function called geometry.Distance. The second declares a method of the type Point, so its name is Point.Distance.

The expression p.Distance is called a selector, because it selects the appropriate Distance method for the receiver p of type Point. Selectors are also used to select fields of struct types, as in p.X. Since methods and fields inhabit the same name space, declaring a method X on the struct type Point would be ambiguous and the compiler will reject it.

Since each type has its own name space for methods, we can use the name Distance for other methods so long as they belong to different types. Let’s define a type Path that represents a sequence of line segments and give it a Distance method too.

// A Path is a journey connecting the points with straight lines.

type Path []Point

// Distance returns the distance traveled along the path.

func (path Path) Distance() float64 {

sum := 0.0

for i := range path {

if i > 0 {

sum += path[i-1].Distance(path[i])

}

}

return sum

}

Path is a named slice type, not a struct type like Point, yet we can still define methods for it. In allowing methods to be associated with any type, Go is unlike many other object-oriented languages. It is often convenient to define additional behaviors for simple types such as numbers, strings, slices, maps, and sometimes even functions. Methods may be declared on any named type defined in the same package, so long as its underlying type is neither a pointer nor an interface.

The two Distance methods have different types. They’re not related to each other at all, though Path.Distance uses Point.Distance internally to compute the length of each segment that connects adjacent points.

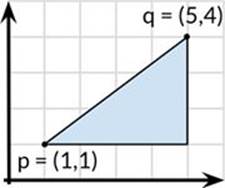

Let’s call the new method to compute the perimeter of a right triangle:

|

perim := Path{ {1, 1}, {5, 1}, {5, 4}, {1, 1}, } fmt.Println(perim.Distance()) // "12" |

|

In the two calls above to methods named Distance, the compiler determines which function to call based on both the method name and the type of the receiver. In the first, path[i-1] has type Point so Point.Distance is called; in the second, perim has type Path, soPath.Distance is called.

All methods of a given type must have unique names, but different types can use the same name for a method, like the Distance methods for Point and Path; there’s no need to qualify function names (for example, PathDistance) to disambiguate. Here we see the first benefit to using methods over ordinary functions: method names can be shorter. The benefit is magnified for calls originating outside the package, since they can use the shorter name and omit the package name:

import "gopl.io/ch6/geometry"

perim := geometry.Path{{1, 1}, {5, 1}, {5, 4}, {1, 1}}

fmt.Println(geometry.PathDistance(perim)) // "12", standalone function

fmt.Println(perim.Distance()) // "12", method of geometry.Path

6.2 Methods with a Pointer Receiver

Because calling a function makes a copy of each argument value, if a function needs to update a variable, or if an argument is so large that we wish to avoid copying it, we must pass the address of the variable using a pointer. The same goes for methods that need to update the receiver variable: we attach them to the pointer type, such as *Point.

func (p *Point) ScaleBy(factor float64) {

p.X *= factor

p.Y *= factor

}

The name of this method is (*Point).ScaleBy. The parentheses are necessary; without them, the expression would be parsed as *(Point.ScaleBy).

In a realistic program, convention dictates that if any method of Point has a pointer receiver, then all methods of Point should have a pointer receiver, even ones that don’t strictly need it. We’ve broken this rule for Point so that we can show both kinds of method.

Named types (Point) and pointers to them (*Point) are the only types that may appear in a receiver declaration. Furthermore, to avoid ambiguities, method declarations are not permitted on named types that are themselves pointer types:

type P *int

func (P) f() { /* ... */ } // compile error: invalid receiver type

The (*Point).ScaleBy method can be called by providing a *Point receiver, like this:

r := &Point{1, 2}

r.ScaleBy(2)

fmt.Println(*r) // "{2, 4}"

or this:

p := Point{1, 2}

pptr := &p

pptr.ScaleBy(2)

fmt.Println(p) // "{2, 4}"

or this:

p := Point{1, 2}

(&p).ScaleBy(2)

fmt.Println(p) // "{2, 4}"

But the last two cases are ungainly. Fortunately, the language helps us here. If the receiver p is a variable of type Point but the method requires a *Point receiver, we can use this shorthand:

p.ScaleBy(2)

and the compiler will perform an implicit &p on the variable. This works only for variables, including struct fields like p.X and array or slice elements like perim[0]. We cannot call a *Point method on a non-addressable Point receiver, because there’s no way to obtain the address of a temporary value.

Point{1, 2}.ScaleBy(2) // compile error: can't take address of Point literal

But we can call a Point method like Point.Distance with a *Point receiver, because there is a way to obtain the value from the address: just load the value pointed to by the receiver. The compiler inserts an implicit * operation for us. These two function calls are equivalent:

pptr.Distance(q)

(*pptr).Distance(q)

Let’s summarize these three cases again, since they are a frequent point of confusion. In every valid method call expression, exactly one of these three statements is true.

Either the receiver argument has the same type as the receiver parameter, for example both have type T or both have type *T:

Point{1, 2}.Distance(q) // Point

pptr.ScaleBy(2) // *Point

Or the receiver argument is a variable of type T and the receiver parameter has type *T. The compiler implicitly takes the address of the variable:

p.ScaleBy(2) // implicit (&p)

Or the receiver argument has type *T and the receiver parameter has type T. The compiler implicitly dereferences the receiver, in other words, loads the value:

pptr.Distance(q) // implicit (*pptr)

If all the methods of a named type T have a receiver type of T itself (not *T), it is safe to copy instances of that type; calling any of its methods necessarily makes a copy. For example, time.Duration values are liberally copied, including as arguments to functions. But if any method has a pointer receiver, you should avoid copying instances of T because doing so may violate internal invariants. For example, copying an instance of bytes.Buffer would cause the original and the copy to alias (§2.3.2) the same underlying array of bytes. Subsequent method calls would have unpredictable effects.

6.2.1 Nil Is a Valid Receiver Value

Just as some functions allow nil pointers as arguments, so do some methods for their receiver, especially if nil is a meaningful zero value of the type, as with maps and slices. In this simple linked list of integers, nil represents the empty list:

// An IntList is a linked list of integers.

// A nil *IntList represents the empty list.

type IntList struct {

Value int

Tail *IntList

}

// Sum returns the sum of the list elements.

func (list *IntList) Sum() int {

if list == nil {

return 0

}

return list.Value + list.Tail.Sum()

}

When you define a type whose methods allow nil as a receiver value, it’s worth pointing this out explicitly in its documentation comment, as we did above.

Here’s part of the definition of the Values type from the net/url package:

net/url

package url

// Values maps a string key to a list of values.

type Values map[string][]string

// Get returns the first value associated with the given key,

// or "" if there are none.

func (v Values) Get(key string) string {

if vs := v[key]; len(vs) > 0 {

return vs[0]

}

return ""

}

// Add adds the value to key.

// It appends to any existing values associated with key.

func (v Values) Add(key, value string) {

v[key] = append(v[key], value)

}

It exposes its representation as a map but also provides methods to simplify access to the map, whose values are slices of strings—it’s a multimap. Its clients can use its intrinsic operators (make, slice literals, m[key], and so on), or its methods, or both, as they prefer:

gopl.io/ch6/urlvalues

m := url.Values{"lang": {"en"}} // direct construction

m.Add("item", "1")

m.Add("item", "2")

fmt.Println(m.Get("lang")) // "en"

fmt.Println(m.Get("q")) // ""

fmt.Println(m.Get("item")) // "1" (first value)

fmt.Println(m["item"]) // "[1 2]" (direct map access)

m = nil

fmt.Println(m.Get("item")) // ""

m.Add("item", "3") // panic: assignment to entry in nil map

In the final call to Get, the nil receiver behaves like an empty map. We could equivalently have written it as Values(nil).Get("item")), but nil.Get("item") will not compile because the type of nil has not been determined. By contrast, the final call to Add panics as it tries to update a nil map.

Because url.Values is a map type and a map refers to its key/value pairs indirectly, any updates and deletions that url.Values.Add makes to the map elements are visible to the caller. However, as with ordinary functions, any changes a method makes to the reference itself, like setting it to nil or making it refer to a different map data structure, will not be reflected in the caller.

6.3 Composing Types by Struct Embedding

Consider the type ColoredPoint:

gopl.io/ch6/coloredpoint

import "image/color"

type Point struct{ X, Y float64 }

type ColoredPoint struct {

Point

Color color.RGBA

}

We could have defined ColoredPoint as a struct of three fields, but instead we embedded a Point to provide the X and Y fields. As we saw in Section 4.4.3, embedding lets us take a syntactic shortcut to defining a ColoredPoint that contains all the fields of Point, plus some more. If we want, we can select the fields of ColoredPoint that were contributed by the embedded Point without mentioning Point:

var cp ColoredPoint

cp.X = 1

fmt.Println(cp.Point.X) // "1"

cp.Point.Y = 2

fmt.Println(cp.Y) // "2"

A similar mechanism applies to the methods of Point. We can call methods of the embedded Point field using a receiver of type ColoredPoint, even though ColoredPoint has no declared methods:

red := color.RGBA{255, 0, 0, 255}

blue := color.RGBA{0, 0, 255, 255}

var p = ColoredPoint{Point{1, 1}, red}

var q = ColoredPoint{Point{5, 4}, blue}

fmt.Println(p.Distance(q.Point)) // "5"

p.ScaleBy(2)

q.ScaleBy(2)

fmt.Println(p.Distance(q.Point)) // "10"

The methods of Point have been promoted to ColoredPoint. In this way, embedding allows complex types with many methods to be built up by the composition of several fields, each providing a few methods.

Readers familiar with class-based object-oriented languages may be tempted to view Point as a base class and ColoredPoint as a subclass or derived class, or to interpret the relationship between these types as if a ColoredPoint “is a” Point. But that would be a mistake. Notice the calls to Distance above. Distance has a parameter of type Point, and q is not a Point, so although q does have an embedded field of that type, we must explicitly select it. Attempting to pass q would be an error:

p.Distance(q) // compile error: cannot use q (ColoredPoint) as Point

A ColoredPoint is not a Point, but it “has a” Point, and it has two additional methods Distance and ScaleBy promoted from Point. If you prefer to think in terms of implementation, the embedded field instructs the compiler to generate additional wrapper methods that delegate to the declared methods, equivalent to these:

func (p ColoredPoint) Distance(q Point) float64 {

return p.Point.Distance(q)

}

func (p *ColoredPoint) ScaleBy(factor float64) {

p.Point.ScaleBy(factor)

}

When Point.Distance is called by the first of these wrapper methods, its receiver value is p.Point, not p, and there is no way for the method to access the ColoredPoint in which the Point is embedded.

The type of an anonymous field may be a pointer to a named type, in which case fields and methods are promoted indirectly from the pointed-to object. Adding another level of indirection lets us share common structures and vary the relationships between objects dynamically. The declaration of ColoredPoint below embeds a *Point:

type ColoredPoint struct {

*Point

Color color.RGBA

}

p := ColoredPoint{&Point{1, 1}, red}

q := ColoredPoint{&Point{5, 4}, blue}

fmt.Println(p.Distance(*q.Point)) // "5"

q.Point = p.Point // p and q now share the same Point

p.ScaleBy(2)

fmt.Println(*p.Point, *q.Point) // "{2 2} {2 2}"

A struct type may have more than one anonymous field. Had we declared ColoredPoint as

type ColoredPoint struct {

Point

color.RGBA

}

then a value of this type would have all the methods of Point, all the methods of RGBA, and any additional methods declared on ColoredPoint directly. When the compiler resolves a selector such as p.ScaleBy to a method, it first looks for a directly declared method namedScaleBy, then for methods promoted once from ColoredPoint’s embedded fields, then for methods promoted twice from embedded fields within Point and RGBA, and so on. The compiler reports an error if the selector was ambiguous because two methods were promoted from the same rank.

Methods can be declared only on named types (like Point) and pointers to them (*Point), but thanks to embedding, it’s possible and sometimes useful for unnamed struct types to have methods too.

Here’s a nice trick to illustrate. This example shows part of a simple cache implemented using two package-level variables, a mutex (§9.2) and the map that it guards:

var (

mu sync.Mutex // guards mapping

mapping = make(map[string]string)

)

func Lookup(key string) string {

mu.Lock()

v := mapping[key]

mu.Unlock()

return v

}

The version below is functionally equivalent but groups together the two related variables in a single package-level variable, cache:

var cache = struct {

sync.Mutex

mapping map[string]string

} {

mapping: make(map[string]string),

}

func Lookup(key string) string {

cache.Lock()

v := cache.mapping[key]

cache.Unlock()

return v

}

The new variable gives more expressive names to the variables related to the cache, and because the sync.Mutex field is embedded within it, its Lock and Unlock methods are promoted to the unnamed struct type, allowing us to lock the cache with a self-explanatory syntax.

6.4 Method Values and Expressions

Usually we select and call a method in the same expression, as in p.Distance(), but it’s possible to separate these two operations. The selector p.Distance yields a method value, a function that binds a method (Point.Distance) to a specific receiver value p. This function can then be invoked without a receiver value; it needs only the non-receiver arguments.

p := Point{1, 2}

q := Point{4, 6}

distanceFromP := p.Distance // method value

fmt.Println(distanceFromP(q)) // "5"

var origin Point // {0, 0}

fmt.Println(distanceFromP(origin)) // "2.23606797749979", √5

scaleP := p.ScaleBy // method value

scaleP(2) // p becomes (2, 4)

scaleP(3) // then (6, 12)

scaleP(10) // then (60, 120)

Method values are useful when a package’s API calls for a function value, and the client’s desired behavior for that function is to call a method on a specific receiver. For example, the function time.AfterFunc calls a function value after a specified delay. This program uses it to launch the rocket r after 10 seconds:

type Rocket struct { /* ... */ }

func (r *Rocket) Launch() { /* ... */ }

r := new(Rocket)

time.AfterFunc(10 * time.Second, func() { r.Launch() })

The method value syntax is shorter:

time.AfterFunc(10 * time.Second, r.Launch)

Related to the method value is the method expression. When calling a method, as opposed to an ordinary function, we must supply the receiver in a special way using the selector syntax. A method expression, written T.f or (*T).f where T is a type, yields a function value with a regular first parameter taking the place of the receiver, so it can be called in the usual way.

p := Point{1, 2}

q := Point{4, 6}

distance := Point.Distance // method expression

fmt.Println(distance(p, q)) // "5"

fmt.Printf("%T\n", distance) // "func(Point, Point) float64"

scale := (*Point).ScaleBy

scale(&p, 2)

fmt.Println(p) // "{2 4}"

fmt.Printf("%T\n", scale) // "func(*Point, float64)"

Method expressions can be helpful when you need a value to represent a choice among several methods belonging to the same type so that you can call the chosen method with many different receivers. In the following example, the variable op represents either the addition or the subtraction method of type Point, and Path.TranslateBy calls it for each point in the Path:

type Point struct{ X, Y float64 }

func (p Point) Add(q Point) Point { return Point{p.X + q.X, p.Y + q.Y} }

func (p Point) Sub(q Point) Point { return Point{p.X - q.X, p.Y - q.Y} }

type Path []Point

func (path Path) TranslateBy(offset Point, add bool) {

var op func(p, q Point) Point

if add {

op = Point.Add

} else {

op = Point.Sub

}

for i := range path {

// Call either path[i].Add(offset) or path[i].Sub(offset).

path[i] = op(path[i], offset)

}

}

6.5 Example: Bit Vector Type

Sets in Go are usually implemented as a map[T]bool, where T is the element type. A set represented by a map is very flexible but, for certain problems, a specialized representation may outperform it. For example, in domains such as dataflow analysis where set elements are small non-negative integers, sets have many elements, and set operations like union and intersection are common, a bit vector is ideal.

A bit vector uses a slice of unsigned integer values or “words,” each bit of which represents a possible element of the set. The set contains i if the i-th bit is set. The following program demonstrates a simple bit vector type with three methods:

gopl.io/ch6/intset

// An IntSet is a set of small non-negative integers.

// Its zero value represents the empty set.

type IntSet struct {

words []uint64

}

// Has reports whether the set contains the non-negative value x.

func (s *IntSet) Has(x int) bool {

word, bit := x/64, uint(x%64)

return word < len(s.words) && s.words[word]&(1<<bit) != 0

}

// Add adds the non-negative value x to the set.

func (s *IntSet) Add(x int) {

word, bit := x/64, uint(x%64)

for word >= len(s.words) {

s.words = append(s.words, 0)

}

s.words[word] |= 1 << bit

}

// UnionWith sets s to the union of s and t.

func (s *IntSet) UnionWith(t *IntSet) {

for i, tword := range t.words {

if i < len(s.words) {

s.words[i] |= tword

} else {

s.words = append(s.words, tword)

}

}

}

Since each word has 64 bits, to locate the bit for x, we use the quotient x/64 as the word index and the remainder x%64 as the bit index within that word. The UnionWith operation uses the bitwise OR operator | to compute the union 64 elements at a time. (We’ll revisit the choice of 64-bit words in Exercise 6.5.)

This implementation lacks many desirable features, some of which are posed as exercises below, but one is hard to live without: way to print an IntSet as a string. Let’s give it a String method as we did with Celsius in Section 2.5:

// String returns the set as a string of the form "{1 2 3}".

func (s *IntSet) String() string {

var buf bytes.Buffer

buf.WriteByte('{')

for i, word := range s.words {

if word == 0 {

continue

}

for j := 0; j < 64; j++ {

if word&(1<<uint(j)) != 0 {

if buf.Len() > len("{") {

buf.WriteByte(' ')

}

fmt.Fprintf(&buf, "%d", 64*i+j)

}

}

}

buf.WriteByte('}')

return buf.String()

}

Notice the similarity of the String method above with intsToString in Section 3.5.4; bytes.Buffer is often used this way in String methods. The fmt package treats types with a String method specially so that values of complicated types can display themselves in a user-friendly manner. Instead of printing the raw representation of the value (a struct in this case), fmt calls the String method. The mechanism relies on interfaces and type assertions, which we’ll explain in Chapter 7.

We can now demonstrate IntSet in action:

var x, y IntSet

x.Add(1)

x.Add(144)

x.Add(9)

fmt.Println(x.String()) // "{1 9 144}"

y.Add(9)

y.Add(42)

fmt.Println(y.String()) // "{9 42}"

x.UnionWith(&y)

fmt.Println(x.String()) // "{1 9 42 144}"

fmt.Println(x.Has(9), x.Has(123)) // "true false"

A word of caution: we declared String and Has as methods of the pointer type *IntSet not out of necessity, but for consistency with the other two methods, which need a pointer receiver because they assign to s.words. Consequently, an IntSet value does not have a Stringmethod, occasionally leading to surprises like this:

fmt.Println(&x) // "{1 9 42 144}"

fmt.Println(x.String()) // "{1 9 42 144}"

fmt.Println(x) // "{[4398046511618 0 65536]}"

In the first case, we print an *IntSet pointer, which does have a String method. In the second case, we call String() on an IntSet variable; the compiler inserts the implicit & operation, giving us a pointer, which has the String method. But in the third case, because the IntSetvalue does not have a String method, fmt.Println prints the representation of the struct instead. It’s important not to forget the & operator. Making String a method of IntSet, not *IntSet, might be a good idea, but this is a case-by-case judgment.

Exercise 6.1: Implement these additional methods:

func (*IntSet) Len() int // return the number of elements

func (*IntSet) Remove(x int) // remove x from the set

func (*IntSet) Clear() // remove all elements from the set

func (*IntSet) Copy() *IntSet // return a copy of the set

Exercise 6.2: Define a variadic (*IntSet).AddAll(...int) method that allows a list of values to be added, such as s.AddAll(1, 2, 3).

Exercise 6.3: (*IntSet).UnionWith computes the union of two sets using |, the word-parallel bitwise OR operator. Implement methods for IntersectWith, DifferenceWith, and SymmetricDifference for the corresponding set operations. (The symmetric difference of two sets contains the elements present in one set or the other but not both.)

Exercise 6.4: Add a method Elems that returns a slice containing the elements of the set, suitable for iterating over with a range loop.

Exercise 6.5: The type of each word used by IntSet is uint64, but 64-bit arithmetic may be inefficient on a 32-bit platform. Modify the program to use the uint type, which is the most efficient unsigned integer type for the platform. Instead of dividing by 64, define a constant holding the effective size of uint in bits, 32 or 64. You can use the perhaps too-clever expression 32 << (^uint(0) >> 63) for this purpose.

6.6 Encapsulation

A variable or method of an object is said to be encapsulated if it is inaccessible to clients of the object. Encapsulation, sometimes called information hiding, is a key aspect of object-oriented programming.

Go has only one mechanism to control the visibility of names: capitalized identifiers are exported from the package in which they are defined, and uncapitalized names are not. The same mechanism that limits access to members of a package also limits access to the fields of a struct or the methods of a type. As a consequence, to encapsulate an object, we must make it a struct.

That’s the reason the IntSet type from the previous section was declared as a struct type even though it has only a single field:

type IntSet struct {

words []uint64

}

We could instead define IntSet as a slice type as follows, though of course we’d have to replace each occurrence of s.words by *s in its methods:

type IntSet []uint64

Although this version of IntSet would be essentially equivalent, it would allow clients from other packages to read and modify the slice directly. Put another way, whereas the expression *s could be used in any package, s.words may appear only in the package that defines IntSet.

Another consequence of this name-based mechanism is that the unit of encapsulation is the package, not the type as in many other languages. The fields of a struct type are visible to all code within the same package. Whether the code appears in a function or a method makes no difference.

Encapsulation provides three benefits. First, because clients cannot directly modify the object’s variables, one need inspect fewer statements to understand the possible values of those variables.

Second, hiding implementation details prevents clients from depending on things that might change, which gives the designer greater freedom to evolve the implementation without breaking API compatibility.

As an example, consider the bytes.Buffer type. It is frequently used to accumulate very short strings, so it is a profitable optimization to reserve a little extra space in the object to avoid memory allocation in this common case. Since Buffer is a struct type, this space takes the form of an extra field of type [64]byte with an uncapitalized name. When this field was added, because it was not exported, clients of Buffer outside the bytes package were unaware of any change except improved performance. Buffer and its Grow method are shown below, simplified for clarity:

type Buffer struct {

buf []byte

initial [64]byte

/* ... */

}

// Grow expands the buffer's capacity, if necessary,

// to guarantee space for another n bytes. [...]

func (b *Buffer) Grow(n int) {

if b.buf == nil {

b.buf = b.initial[:0] // use preallocated space initially

}

if len(b.buf)+n > cap(b.buf) {

buf := make([]byte, b.Len(), 2*cap(b.buf) + n)

copy(buf, b.buf)

b.buf = buf

}

}

The third benefit of encapsulation, and in many cases the most important, is that it prevents clients from setting an object’s variables arbitrarily. Because the object’s variables can be set only by functions in the same package, the author of that package can ensure that all those functions maintain the object’s internal invariants. For example, the Counter type below permits clients to increment the counter or to reset it to zero, but not to set it to some arbitrary value:

type Counter struct { n int }

func (c *Counter) N() int { return c.n }

func (c *Counter) Increment() { c.n++ }

func (c *Counter) Reset() { c.n = 0 }

Functions that merely access or modify internal values of a type, such as the methods of the Logger type from log package, below, are called getters and setters. However, when naming a getter method, we usually omit the Get prefix. This preference for brevity extends to all methods, not just field accessors, and to other redundant prefixes as well, such as Fetch, Find, and Lookup.

package log

type Logger struct {

flags int

prefix string

// ...

}

func (l *Logger) Flags() int

func (l *Logger) SetFlags(flag int)

func (l *Logger) Prefix() string

func (l *Logger) SetPrefix(prefix string)

Go style does not forbid exported fields. Of course, once exported, a field cannot be unexported without an incompatible change to the API, so the initial choice should be deliberate and should consider the complexity of the invariants that must be maintained, the likelihood of future changes,and the quantity of client code that would be affected by a change.

Encapsulation is not always desirable. By revealing its representation as an int64 number of nanoseconds, time.Duration lets us use all the usual arithmetic and comparison operations with durations, and even to define constants of this type:

const day = 24 * time.Hour

fmt.Println(day.Seconds()) // "86400"

As another example, contrast IntSet with the geometry.Path type from the beginning of this chapter. Path was defined as a slice type, allowing its clients to construct instances using the slice literal syntax, to iterate over its points using a range loop, and so on, whereas these operations are denied to clients of IntSet.

Here’s the crucial difference: geometry.Path is intrinsically a sequence of points, no more and no less, and we don’t foresee adding new fields to it, so it makes sense for the geometry package to reveal that Path is a slice. In contrast, an IntSet merely happens to be represented as a[]uint64 slice. It could have been represented using []uint, or something completely different for sets that are sparse or very small, and it might perhaps benefit from additional features like an extra field to record the number of elements in the set. For these reasons, it makes sense forIntSet to be opaque.

In this chapter, we learned how to associate methods with named types, and how to call those methods. Although methods are crucial to object-oriented programming, they’re only half the picture. To complete it, we need interfaces, the subject of the next chapter.