The Go Programming Language (2016)

8. Goroutines and Channels

Concurrent programming, the expression of a program as a composition of several autonomous activities, has never been more important than it is today. Web servers handle requests for thousands of clients at once. Tablet and phone apps render animations in the user interface while simultaneously performing computation and network requests in the background. Even traditional batch problems—read some data, compute, write some output—use concurrency to hide the latency of I/O operations and to exploit a modern computer’s many processors, which every year grow in number but not in speed.

Go enables two styles of concurrent programming. This chapter presents goroutines and channels, which support communicating sequential processes or CSP, a model of concurrency in which values are passed between independent activities (goroutines) but variables are for the most part confined to a single activity. Chapter 9 covers some aspects of the more traditional model of shared memory multithreading, which will be familiar if you’ve used threads in other mainstream languages. Chapter 9 also points out some important hazards and pitfalls of concurrent programming that we won’t delve into in this chapter.

Even though Go’s support for concurrency is one of its great strengths, reasoning about concurrent programs is inherently harder than about sequential ones, and intuitions acquired from sequential programming may at times lead us astray. If this is your first encounter with concurrency, we recommend spending a little extra time thinking about the examples in these two chapters.

8.1 Goroutines

In Go, each concurrently executing activity is called a goroutine. Consider a program that has two functions, one that does some computation and one that writes some output, and assume that neither function calls the other. A sequential program may call one function and then call the other, but in a concurrent program with two or more goroutines, calls to both functions can be active at the same time. We’ll see such a program in a moment.

If you have used operating system threads or threads in other languages, then you can assume for now that a goroutine is similar to a thread, and you’ll be able to write correct programs. The differences between threads and goroutines are essentially quantitative, not qualitative, and will be described in Section 9.8.

When a program starts, its only goroutine is the one that calls the main function, so we call it the main goroutine. New goroutines are created by the go statement. Syntactically, a go statement is an ordinary function or method call prefixed by the keyword go. A go statement causes the function to be called in a newly created goroutine. The go statement itself completes immediately:

f() // call f(); wait for it to return

go f() // create a new goroutine that calls f(); don't wait

In the example below, the main goroutine computes the 45th Fibonacci number. Since it uses the terribly inefficient recursive algorithm, it runs for an appreciable time, during which we’d like to provide the user with a visual indication that the program is still running, by displaying an animated textual “spinner.”

gopl.io/ch8/spinner

func main() {

go spinner(100 * time.Millisecond)

const n = 45

fibN := fib(n) // slow

fmt.Printf("\rFibonacci(%d) = %d\n", n, fibN)

}

func spinner(delay time.Duration) {

for {

for _, r := range `-\|/` {

fmt.Printf("\r%c", r)

time.Sleep(delay)

}

}

}

func fib(x int) int {

if x < 2 {

return x

}

return fib(x-1) + fib(x-2)

}

After several seconds of animation, the fib(45) call returns and the main function prints its result:

Fibonacci(45) = 1134903170

The main function then returns. When this happens, all goroutines are abruptly terminated and the program exits. Other than by returning from main or exiting the program, there is no programmatic way for one goroutine to stop another, but as we will see later, there are ways to communicate with a goroutine to request that it stop itself.

Notice how the program is expressed as the composition of two autonomous activities, spinning and Fibonacci computation. Each is written as a separate function but both make progress concurrently.

8.2 Example: Concurrent Clock Server

Networking is a natural domain in which to use concurrency since servers typically handle many connections from their clients at once, each client being essentially independent of the others. In this section, we’ll introduce the net package, which provides the components for building networked client and server programs that communicate over TCP, UDP, or Unix domain sockets. The net/http package we’ve been using since Chapter 1 is built on top of functions from the net package.

Our first example is a sequential clock server that writes the current time to the client once per second:

gopl.io/ch8/clock1

// Clock1 is a TCP server that periodically writes the time.

package main

import (

"io"

"log"

"net"

"time"

)

func main() {

listener, err := net.Listen("tcp", "localhost:8000")

if err != nil {

log.Fatal(err)

}

for {

conn, err := listener.Accept()

if err != nil {

log.Print(err) // e.g., connection aborted

continue

}

handleConn(conn) // handle one connection at a time

}

}

func handleConn(c net.Conn) {

defer c.Close()

for {

_, err := io.WriteString(c, time.Now().Format("15:04:05\n"))

if err != nil {

return // e.g., client disconnected

}

time.Sleep(1 * time.Second)

}

}

The Listen function creates a net.Listener, an object that listens for incoming connections on a network port, in this case TCP port localhost:8000. The listener’s Accept method blocks until an incoming connection request is made, then returns a net.Conn object representing the connection.

The handleConn function handles one complete client connection. In a loop, it writes the current time, time.Now(), to the client. Since net.Conn satisfies the io.Writer interface, we can write directly to it. The loop ends when the write fails, most likely because the client has disconnected, at which point handleConn closes its side of the connection using a deferred call to Close and goes back to waiting for another connection request.

The time.Time.Format method provides a way to format date and time information by example. Its argument is a template indicating how to format a reference time, specifically Mon Jan 2 03:04:05PM 2006 UTC-0700. The reference time has eight components (day of the week, month, day of the month, and so on). Any collection of them can appear in the Format string in any order and in a number of formats; the selected components of the date and time will be displayed in the selected formats. Here we are just using the hour, minute, and second of the time. The time package defines templates for many standard time formats, such as time.RFC1123. The same mechanism is used in reverse when parsing a time using time.Parse.

To connect to the server, we’ll need a client program such as nc (“netcat”), a standard utility program for manipulating network connections:

$ go build gopl.io/ch8/clock1

$ ./clock1 &

$ nc localhost 8000

13:58:54

13:58:55

13:58:56

13:58:57

^C

The client displays the time sent by the server each second until we interrupt the client with Control-C, which on Unix systems is echoed as ^C by the shell. If nc or netcat is not installed on your system, you can use telnet or this simple Go version of netcat that uses net.Dial to connect to a TCP server:

gopl.io/ch8/netcat1

// Netcat1 is a read-only TCP client.

package main

import (

"io"

"log"

"net"

"os"

)

func main() {

conn, err := net.Dial("tcp", "localhost:8000")

if err != nil {

log.Fatal(err)

}

defer conn.Close()

mustCopy(os.Stdout, conn)

}

func mustCopy(dst io.Writer, src io.Reader) {

if _, err := io.Copy(dst, src); err != nil {

log.Fatal(err)

}

}

This program reads data from the connection and writes it to the standard output until an end-of-file condition or an error occurs. The mustCopy function is a utility used in several examples in this section. Let’s run two clients at the same time on different terminals, one shown to the left and one to the right:

$ go build gopl.io/ch8/netcat1

$ ./netcat1

13:58:54 $ ./netcat1

13:58:55

13:58:56

^C

13:58:57

13:58:58

13:58:59

^C

$ killall clock1

The killall command is a Unix utility that kills all processes with the given name.

The second client must wait until the first client is finished because the server is sequential; it deals with only one client at a time. Just one small change is needed to make the server concurrent: adding the go keyword to the call to handleConn causes each call to run in its own goroutine.

gopl.io/ch8/clock2

for {

conn, err := listener.Accept()

if err != nil {

log.Print(err) // e.g., connection aborted

continue

}

go handleConn(conn) // handle connections concurrently

}

Now, multiple clients can receive the time at once:

$ go build gopl.io/ch8/clock2

$ ./clock2 &

$ go build gopl.io/ch8/netcat1

$ ./netcat1

14:02:54 $ ./netcat1

14:02:55 14:02:55

14:02:56 14:02:56

14:02:57 ^C

14:02:58

14:02:59 $ ./netcat1

14:03:00 14:03:00

14:03:01 14:03:01

^C 14:03:02

^C

$ killall clock2

Exercise 8.1: Modify clock2 to accept a port number, and write a program, clockwall, that acts as a client of several clock servers at once, reading the times from each one and displaying the results in a table, akin to the wall of clocks seen in some business offices. If you have access to geographically distributed computers, run instances remotely; otherwise run local instances on different ports with fake time zones.

$ TZ=US/Eastern ./clock2 -port 8010 &

$ TZ=Asia/Tokyo ./clock2 -port 8020 &

$ TZ=Europe/London ./clock2 -port 8030 &

$ clockwall NewYork=localhost:8010 London=localhost:8020 Tokyo=localhost:8030

Exercise 8.2: Implement a concurrent File Transfer Protocol (FTP) server. The server should interpret commands from each client such as cd to change directory, ls to list a directory, get to send the contents of a file, and close to close the connection. You can use the standard ftpcommand as the client, or write your own.

8.3 Example: Concurrent Echo Server

The clock server used one goroutine per connection. In this section, we’ll build an echo server that uses multiple goroutines per connection. Most echo servers merely write whatever they read, which can be done with this trivial version of handleConn:

func handleConn(c net.Conn) {

io.Copy(c, c) // NOTE: ignoring errors

c.Close()

}

A more interesting echo server might simulate the reverberations of a real echo, with the response loud at first ("HELLO!"), then moderate ("Hello!") after a delay, then quiet ("hello!") before fading to nothing, as in this version of handleConn:

gopl.io/ch8/reverb1

func echo(c net.Conn, shout string, delay time.Duration) {

fmt.Fprintln(c, "\t", strings.ToUpper(shout))

time.Sleep(delay)

fmt.Fprintln(c, "\t", shout)

time.Sleep(delay)

fmt.Fprintln(c, "\t", strings.ToLower(shout))

}

func handleConn(c net.Conn) {

input := bufio.NewScanner(c)

for input.Scan() {

echo(c, input.Text(), 1*time.Second)

}

// NOTE: ignoring potential errors from input.Err()

c.Close()

}

We’ll need to upgrade our client program so that it sends terminal input to the server while also copying the server response to the output, which presents another opportunity to use concurrency:

gopl.io/ch8/netcat2

func main() {

conn, err := net.Dial("tcp", "localhost:8000")

if err != nil {

log.Fatal(err)

}

defer conn.Close()

go mustCopy(os.Stdout, conn)

mustCopy(conn, os.Stdin)

}

While the main goroutine reads the standard input and sends it to the server, a second goroutine reads and prints the server’s response. When the main goroutine encounters the end of the input, for example, after the user types Control-D (^D) at the terminal (or the equivalent Control-Z on Microsoft Windows), the program stops, even if the other goroutine still has work to do. (We’ll see how to make the program wait for both sides to finish once we’ve introduced channels in Section 8.4.1.)

In the session below, the client’s input is left-aligned and the server’s responses are indented. The client shouts at the echo server three times:

$ go build gopl.io/ch8/reverb1

$ ./reverb1 &

$ go build gopl.io/ch8/netcat2

$ ./netcat2

Hello?

HELLO?

Hello?

hello?

Is there anybody there?

IS THERE ANYBODY THERE?

Yooo-hooo!

Is there anybody there?

is there anybody there?

YOOO-HOOO!

Yooo-hooo!

yooo-hooo!

^D

$ killall reverb1

Notice that the third shout from the client is not dealt with until the second shout has petered out, which is not very realistic. A real echo would consist of the composition of the three independent shouts. To simulate it, we’ll need more goroutines. Again, all we need to do is add the gokeyword, this time to the call to echo:

gopl.io/ch8/reverb2

func handleConn(c net.Conn) {

input := bufio.NewScanner(c)

for input.Scan() {

go echo(c, input.Text(), 1*time.Second)

}

// NOTE: ignoring potential errors from input.Err()

c.Close()

}

The arguments to the function started by go are evaluated when the go statement itself is executed; thus input.Text() is evaluated in the main goroutine.

Now the echoes are concurrent and overlap in time:

$ go build gopl.io/ch8/reverb2

$ ./reverb2 &

$ ./netcat2

Is there anybody there?

IS THERE ANYBODY THERE?

Yooo-hooo!

Is there anybody there?

YOOO-HOOO!

is there anybody there?

Yooo-hooo!

yooo-hooo!

^D

$ killall reverb2

All that was required to make the server use concurrency, not just to handle connections from multiple clients but even within a single connection, was the insertion of two go keywords.

However in adding these keywords, we had to consider carefully that it is safe to call methods of net.Conn concurrently, which is not true for most types. We’ll discuss the crucial concept of concurrency safety in the next chapter.

8.4 Channels

If goroutines are the activities of a concurrent Go program, channels are the connections between them. A channel is a communication mechanism that lets one goroutine send values to another goroutine. Each channel is a conduit for values of a particular type, called the channel’s element type. The type of a channel whose elements have type int is written chan int.

To create a channel, we use the built-in make function:

ch := make(chan int) // ch has type 'chan int'

As with maps, a channel is a reference to the data structure created by make. When we copy a channel or pass one as an argument to a function, we are copying a reference, so caller and callee refer to the same data structure. As with other reference types, the zero value of a channel is nil.

Two channels of the same type may be compared using ==. The comparison is true if both are references to the same channel data structure. A channel may also be compared to nil.

A channel has two principal operations, send and receive, collectively known as communications. A send statement transmits a value from one goroutine, through the channel, to another goroutine executing a corresponding receive expression. Both operations are written using the <-operator. In a send statement, the <- separates the channel and value operands. In a receive expression, <- precedes the channel operand. A receive expression whose result is not used is a valid statement.

ch <- x // a send statement

x = <-ch // a receive expression in an assignment statement

<-ch // a receive statement; result is discarded

Channels support a third operation, close, which sets a flag indicating that no more values will ever be sent on this channel; subsequent attempts to send will panic. Receive operations on a closed channel yield the values that have been sent until no more values are left; any receive operations thereafter complete immediately and yield the zero value of the channel’s element type.

To close a channel, we call the built-in close function:

close(ch)

A channel created with a simple call to make is called an unbuffered channel, but make accepts an optional second argument, an integer called the channel’s capacity. If the capacity is non-zero, make creates a buffered channel.

ch = make(chan int) // unbuffered channel

ch = make(chan int, 0) // unbuffered channel

ch = make(chan int, 3) // buffered channel with capacity 3

We’ll look at unbuffered channels first and buffered channels in Section 8.4.4.

8.4.1 Unbuffered Channels

A send operation on an unbuffered channel blocks the sending goroutine until another goroutine executes a corresponding receive on the same channel, at which point the value is transmitted and both goroutines may continue. Conversely, if the receive operation was attempted first, the receiving goroutine is blocked until another goroutine performs a send on the same channel.

Communication over an unbuffered channel causes the sending and receiving goroutines to synchronize. Because of this, unbuffered channels are sometimes called synchronous channels. When a value is sent on an unbuffered channel, the receipt of the value happens before the reawakening of the sending goroutine.

In discussions of concurrency, when we say x happens before y, we don’t mean merely that x occurs earlier in time than y; we mean that it is guaranteed to do so and that all its prior effects, such as updates to variables, are complete and that you may rely on them.

When x neither happens before y nor after y, we say that x is concurrent with y. This doesn’t mean that x and y are necessarily simultaneous, merely that we cannot assume anything about their ordering. As we’ll see in the next chapter, it’s necessary to order certain events during the program’s execution to avoid the problems that arise when two goroutines access the same variable concurrently.

The client program in Section 8.3 copies input to the server in its main goroutine, so the client program terminates as soon as the input stream closes, even if the background goroutine is still working. To make the program wait for the background goroutine to complete before exiting, we use a channel to synchronize the two goroutines:

gopl.io/ch8/netcat3

func main() {

conn, err := net.Dial("tcp", "localhost:8000")

if err != nil {

log.Fatal(err)

}

done := make(chan struct{})

go func() {

io.Copy(os.Stdout, conn) // NOTE: ignoring errors

log.Println("done")

done <- struct{}{} // signal the main goroutine

}()

mustCopy(conn, os.Stdin)

conn.Close()

<-done // wait for background goroutine to finish

}

When the user closes the standard input stream, mustCopy returns and the main goroutine calls conn.Close(), closing both halves of the network connection. Closing the write half of the connection causes the server to see an end-of-file condition. Closing the read half causes the background goroutine’s call to io.Copy to return a “read from closed connection” error, which is why we’ve removed the error logging; Exercise 8.3 suggests a better solution. (Notice that the go statement calls a literal function, a common construction.)

Before it returns, the background goroutine logs a message, then sends a value on the done channel. The main goroutine waits until it has received this value before returning. As a result, the program always logs the "done" message before exiting.

Messages sent over channels have two important aspects. Each message has a value, but sometimes the fact of communication and the moment at which it occurs are just as important. We call messages events when we wish to stress this aspect. When the event carries no additional information, that is, its sole purpose is synchronization, we’ll emphasize this by using a channel whose element type is struct{}, though it’s common to use a channel of bool or int for the same purpose since done <- 1 is shorter than done <- struct{}{}.

Exercise 8.3: In netcat3, the interface value conn has the concrete type *net.TCPConn, which represents a TCP connection. A TCP connection consists of two halves that may be closed independently using its CloseRead and CloseWrite methods. Modify the main goroutine ofnetcat3 to close only the write half of the connection so that the program will continue to print the final echoes from the reverb1 server even after the standard input has been closed. (Doing this for the reverb2 server is harder; see Exercise 8.4.)

8.4.2 Pipelines

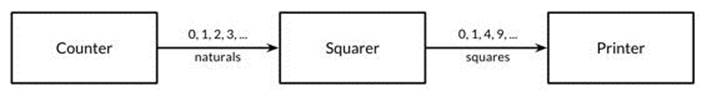

Channels can be used to connect goroutines together so that the output of one is the input to another. This is called a pipeline. The program below consists of three goroutines connected by two channels, as shown schematically in Figure 8.1.

Figure 8.1. A three-stage pipeline.

The first goroutine, counter, generates the integers 0, 1, 2, ..., and sends them over a channel to the second goroutine, squarer, which receives each value, squares it, and sends the result over another channel to the third goroutine, printer, which receives the squared values and prints them. For clarity of this example, we have intentionally chosen very simple functions, though of course they are too computationally trivial to warrant their own goroutines in a realistic program.

gopl.io/ch8/pipeline1

func main() {

naturals := make(chan int)

squares := make(chan int)

// Counter

go func() {

for x := 0; ; x++ {

naturals <- x

}

}()

// Squarer

go func() {

for {

x := <-naturals

squares <- x * x

}

}()

// Printer (in main goroutine)

for {

fmt.Println(<-squares)

}

}

As you might expect, the program prints the infinite series of squares 0, 1, 4, 9, and so on. Pipelines like this may be found in long-running server programs where channels are used for lifelong communication between goroutines containing infinite loops. But what if we want to send only a finite number of values through the pipeline?

If the sender knows that no further values will ever be sent on a channel, it is useful to communicate this fact to the receiver goroutines so that they can stop waiting. This is accomplished by closing the channel using the built-in close function:

close(naturals)

After a channel has been closed, any further send operations on it will panic. After the closed channel has been drained, that is, after the last sent element has been received, all subsequent receive operations will proceed without blocking but will yield a zero value. Closing the naturalschannel above would cause the squarer’s loop to spin as it receives a never-ending stream of zero values, and to send these zeros to the printer.

There is no way to test directly whether a channel has been closed, but there is a variant of the receive operation that produces two results: the received channel element, plus a boolean value, conventionally called ok, which is true for a successful receive and false for a receive on a closed and drained channel. Using this feature, we can modify the squarer’s loop to stop when the naturals channel is drained and close the squares channel in turn.

// Squarer

go func() {

for {

x, ok := <-naturals

if !ok {

break // channel was closed and drained

}

squares <- x * x

}

close(squares)

}()

Because the syntax above is clumsy and this pattern is common, the language lets us use a range loop to iterate over channels too. This is a more convenient syntax for receiving all the values sent on a channel and terminating the loop after the last one.

In the pipeline below, when the counter goroutine finishes its loop after 100 elements, it closes the naturals channel, causing the squarer to finish its loop and close the squares channel. (In a more complex program, it might make sense for the counter and squarer functions to defer the calls to close at the outset.) Finally, the main goroutine finishes its loop and the program exits.

gopl.io/ch8/pipeline2

func main() {

naturals := make(chan int)

squares := make(chan int)

// Counter

go func() {

for x := 0; x < 100; x++ {

naturals <- x

}

close(naturals)

}()

// Squarer

go func() {

for x := range naturals {

squares <- x * x

}

close(squares)

}()

// Printer (in main goroutine)

for x := range squares {

fmt.Println(x)

}

}

You needn’t close every channel when you’ve finished with it. It’s only necessary to close a channel when it is important to tell the receiving goroutines that all data have been sent. A channel that the garbage collector determines to be unreachable will have its resources reclaimed whether or not it is closed. (Don’t confuse this with the close operation for open files. It is important to call the Close method on every file when you’ve finished with it.)

Attempting to close an already-closed channel causes a panic, as does closing a nil channel. Closing channels has another use as a broadcast mechanism, which we’ll cover in Section 8.9.

8.4.3 Unidirectional Channel Types

As programs grow, it is natural to break up large functions into smaller pieces. Our previous example used three goroutines, communicating over two channels, which were local variables of main. The program naturally divides into three functions:

func counter(out chan int)

func squarer(out, in chan int)

func printer(in chan int)

The squarer function, sitting in the middle of the pipeline, takes two parameters, the input channel and the output channel. Both have the same type, but their intended uses are opposite: in is only to be received from, and out is only to be sent to. The names in and out convey this intention, but still, nothing prevents squarer from sending to in or receiving from out.

This arrangement is typical. When a channel is supplied as a function parameter, it is nearly always with the intent that it be used exclusively for sending or exclusively for receiving.

To document this intent and prevent misuse, the Go type system provides unidirectional channel types that expose only one or the other of the send and receive operations. The type chan<- int, a send-only channel of int, allows sends but not receives. Conversely, the type <-chan int, a receive-only channel of int, allows receives but not sends. (The position of the <- arrow relative to the chan keyword is a mnemonic.) Violations of this discipline are detected at compile time.

Since the close operation asserts that no more sends will occur on a channel, only the sending goroutine is in a position to call it, and for this reason it is a compile-time error to attempt to close a receive-only channel.

Here’s the squaring pipeline once more, this time with unidirectional channel types:

gopl.io/ch8/pipeline3

func counter(out chan<- int) {

for x := 0; x < 100; x++ {

out <- x

}

close(out)

}

func squarer(out chan<- int, in <-chan int) {

for v := range in {

out <- v * v

}

close(out)

}

func printer(in <-chan int) {

for v := range in {

fmt.Println(v)

}

}

func main() {

naturals := make(chan int)

squares := make(chan int)

go counter(naturals)

go squarer(squares, naturals)

printer(squares)

}

The call counter(naturals) implicitly converts naturals, a value of type chan int, to the type of the parameter, chan<- int. The printer(squares) call does a similar implicit conversion to <-chan int. Conversions from bidirectional to unidirectional channel types are permitted in any assignment. There is no going back, however: once you have a value of a unidirectional type such as chan<- int, there is no way to obtain from it a value of type chan int that refers to the same channel data structure.

8.4.4 Buffered Channels

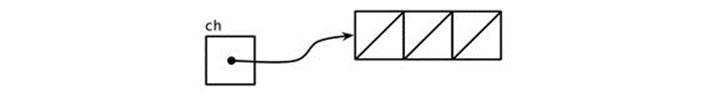

A buffered channel has a queue of elements. The queue’s maximum size is determined when it is created, by the capacity argument to make. The statement below creates a buffered channel capable of holding three string values. Figure 8.2 is a graphical representation of ch and the channel to which it refers.

ch = make(chan string, 3)

Figure 8.2. An empty buffered channel.

A send operation on a buffered channel inserts an element at the back of the queue, and a receive operation removes an element from the front. If the channel is full, the send operation blocks its goroutine until space is made available by another goroutine’s receive. Conversely, if the channel is empty, a receive operation blocks until a value is sent by another goroutine.

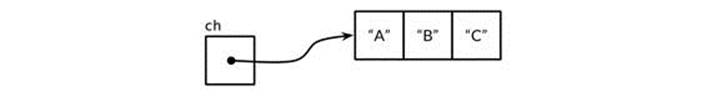

We can send up to three values on this channel without the goroutine blocking:

ch <- "A"

ch <- "B"

ch <- "C"

At this point, the channel is full (Figure 8.3), and a fourth send statement would block.

Figure 8.3. A full buffered channel.

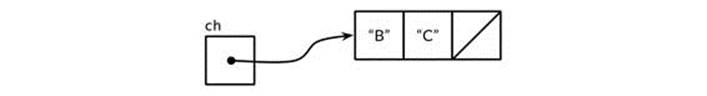

If we receive one value,

fmt.Println(<-ch) // "A"

the channel is neither full nor empty (Figure 8.4), so either a send operation or a receive operation could proceed without blocking. In this way, the channel’s buffer decouples the sending and receiving goroutines.

Figure 8.4. A partially full buffered channel.

In the unlikely event that a program needs to know the channel’s buffer capacity, it can be obtained by calling the built-in cap function:

fmt.Println(cap(ch)) // "3"

When applied to a channel, the built-in len function returns the number of elements currently buffered. Since in a concurrent program this information is likely to be stale as soon as it is retrieved, its value is limited, but it could conceivably be useful during fault diagnosis or performance optimization.

fmt.Println(len(ch)) // "2"

After two more receive operations the channel is empty again, and a fourth would block:

fmt.Println(<-ch) // "B"

fmt.Println(<-ch) // "C"

In this example, the send and receive operations were all performed by the same goroutine, but in real programs they are usually executed by different goroutines. Novices are sometimes tempted to use buffered channels within a single goroutine as a queue, lured by their pleasingly simple syntax, but this is a mistake. Channels are deeply connected to goroutine scheduling, and without another goroutine receiving from the channel, a sender—and perhaps the whole program—risks becoming blocked forever. If all you need is a simple queue, make one using a slice.

The example below shows an application of a buffered channel. It makes parallel requests to three mirrors, that is, equivalent but geographically distributed servers. It sends their responses over a buffered channel, then receives and returns only the first response, which is the quickest one to arrive. Thus mirroredQuery returns a result even before the two slower servers have responded. (Incidentally, it’s quite normal for several goroutines to send values to the same channel concurrently, as in this example, or to receive from the same channel.)

func mirroredQuery() string {

responses := make(chan string, 3)

go func() { responses <- request("asia.gopl.io") }()

go func() { responses <- request("europe.gopl.io") }()

go func() { responses <- request("americas.gopl.io") }()

return <-responses // return the quickest response

}

func request(hostname string) (response string) { /* ... */ }

Had we used an unbuffered channel, the two slower goroutines would have gotten stuck trying to send their responses on a channel from which no goroutine will ever receive. This situation, called a goroutine leak, would be a bug. Unlike garbage variables, leaked goroutines are not automatically collected, so it is important to make sure that goroutines terminate themselves when no longer needed.

The choice between unbuffered and buffered channels, and the choice of a buffered channel’s capacity, may both affect the correctness of a program. Unbuffered channels give stronger synchronization guarantees because every send operation is synchronized with its corresponding receive; with buffered channels, these operations are decoupled. Also, when we know an upper bound on the number of values that will be sent on a channel, it’s not unusual to create a buffered channel of that size and perform all the sends before the first value is received. Failure to allocate sufficient buffer capacity would cause the program to deadlock.

Channel buffering may also affect program performance. Imagine three cooks in a cake shop, one baking, one icing, and one inscribing each cake before passing it on to the next cook in the assembly line. In a kitchen with little space, each cook that has finished a cake must wait for the next cook to become ready to accept it; this rendezvous is analogous to communication over an unbuffered channel.

If there is space for one cake between each cook, a cook may place a finished cake there and immediately start work on the next; this is analogous to a buffered channel with capacity 1. So long as the cooks work at about the same rate on average, most of these handovers proceed quickly, smoothing out transient differences in their respective rates. More space between cooks—larger buffers—can smooth out bigger transient variations in their rates without stalling the assembly line, such as happens when one cook takes a short break, then later rushes to catch up.

On the other hand, if an earlier stage of the assembly line is consistently faster than the following stage, the buffer between them will spend most of its time full. Conversely, if the later stage is faster, the buffer will usually be empty. A buffer provides no benefit in this case.

The assembly line metaphor is a useful one for channels and goroutines. For example, if the second stage is more elaborate, a single cook may not be able to keep up with the supply from the first cook or meet the demand from the third. To solve the problem, we could hire another cook to help the second, performing the same task but working independently. This is analogous to creating another goroutine communicating over the same channels.

We don’t have space to show it here, but the gopl.io/ch8/cake package simulates this cake shop, with several parameters you can vary. It includes benchmarks (§11.4) for a few of the scenarios described above.

8.5 Looping in Parallel

In this section, we’ll explore some common concurrency patterns for executing all the iterations of a loop in parallel. We’ll consider the problem of producing thumbnail-size images from a set of full-size ones. The gopl.io/ch8/thumbnail package provides an ImageFile function that can scale a single image. We won’t show its implementation but it can be downloaded from gopl.io.

gopl.io/ch8/thumbnail

package thumbnail

// ImageFile reads an image from infile and writes

// a thumbnail-size version of it in the same directory.

// It returns the generated file name, e.g., "foo.thumb.jpg".

func ImageFile(infile string) (string, error)

The program below loops over a list of image file names and produces a thumbnail for each one:

gopl.io/ch8/thumbnail

// makeThumbnails makes thumbnails of the specified files.

func makeThumbnails(filenames []string) {

for _, f := range filenames {

if _, err := thumbnail.ImageFile(f); err != nil {

log.Println(err)

}

}

}

Obviously the order in which we process the files doesn’t matter, since each scaling operation is independent of all the others. Problems like this that consist entirely of subproblems that are completely independent of each other are described as embarrassingly parallel. Embarrassingly parallel problems are the easiest kind to implement concurrently and enjoy performance that scales linearly with the amount of parallelism.

Let’s execute all these operations in parallel, thereby hiding the latency of the file I/O and using multiple CPUs for the image-scaling computations. Our first attempt at a concurrent version just adds a go keyword. We’ll ignore errors for now and address them later.

// NOTE: incorrect!

func makeThumbnails2(filenames []string) {

for _, f := range filenames {

go thumbnail.ImageFile(f) // NOTE: ignoring errors

}

}

This version runs really fast—too fast, in fact, since it takes less time than the original, even when the slice of file names contains only a single element. If there’s no parallelism, how can the concurrent version possibly run faster? The answer is that makeThumbnails returns before it has finished doing what it was supposed to do. It starts all the goroutines, one per file name, but doesn’t wait for them to finish.

There is no direct way to wait until a goroutine has finished, but we can change the inner goroutine to report its completion to the outer goroutine by sending an event on a shared channel. Since we know that there are exactly len(filenames) inner goroutines, the outer goroutine need only count that many events before it returns:

// makeThumbnails3 makes thumbnails of the specified files in parallel.

func makeThumbnails3(filenames []string) {

ch := make(chan struct{})

for _, f := range filenames {

go func(f string) {

thumbnail.ImageFile(f) // NOTE: ignoring errors

ch <- struct{}{}

}(f)

}

// Wait for goroutines to complete.

for range filenames {

<-ch

}

}

Notice that we passed the value of f as an explicit argument to the literal function instead of using the declaration of f from the enclosing for loop:

for _, f := range filenames {

go func() {

thumbnail.ImageFile(f) // NOTE: incorrect!

// ...

}()

}

Recall the problem of loop variable capture inside an anonymous function, described in Section 5.6.1. Above, the single variable f is shared by all the anonymous function values and updated by successive loop iterations. By the time the new goroutines start executing the literal function, thefor loop may have updated f and started another iteration or (more likely) finished entirely, so when these goroutines read the value of f, they all observe it to have the value of the final element of the slice. By adding an explicit parameter, we ensure that we use the value of f that is current when the go statement is executed.

What if we want to return values from each worker goroutine to the main one? If the call to thumbnail.ImageFile fails to create a file, it returns an error. The next version of makeThumbnails returns the first error it receives from any of the scaling operations:

// makeThumbnails4 makes thumbnails for the specified files in parallel.

// It returns an error if any step failed.

func makeThumbnails4(filenames []string) error {

errors := make(chan error)

for _, f := range filenames {

go func(f string) {

_, err := thumbnail.ImageFile(f)

errors <- err

}(f)

}

for range filenames {

if err := <-errors; err != nil {

return err // NOTE: incorrect: goroutine leak!

}

}

return nil

}

This function has a subtle bug. When it encounters the first non-nil error, it returns the error to the caller, leaving no goroutine draining the errors channel. Each remaining worker goroutine will block forever when it tries to send a value on that channel, and will never terminate. This situation, a goroutine leak (§8.4.4), may cause the whole program to get stuck or to run out of memory.

The simplest solution is to use a buffered channel with sufficient capacity that no worker goroutine will block when it sends a message. (An alternative solution is to create another goroutine to drain the channel while the main goroutine returns the first error without delay.)

The next version of makeThumbnails uses a buffered channel to return the names of the generated image files along with any errors.

// makeThumbnails5 makes thumbnails for the specified files in parallel.

// It returns the generated file names in an arbitrary order,

// or an error if any step failed.

func makeThumbnails5(filenames []string) (thumbfiles []string, err error) {

type item struct {

thumbfile string

err error

}

ch := make(chan item, len(filenames))

for _, f := range filenames {

go func(f string) {

var it item

it.thumbfile, it.err = thumbnail.ImageFile(f)

ch <- it

}(f)

}

for range filenames {

it := <-ch

if it.err != nil {

return nil, it.err

}

thumbfiles = append(thumbfiles, it.thumbfile)

}

return thumbfiles, nil

}

Our final version of makeThumbnails, below, returns the total number of bytes occupied by the new files. Unlike the previous versions, however, it receives the file names not as a slice but over a channel of strings, so we cannot predict the number of loop iterations.

To know when the last goroutine has finished (which may not be the last one to start), we need to increment a counter before each goroutine starts and decrement it as each goroutine finishes. This demands a special kind of counter, one that can be safely manipulated from multiple goroutines and that provides a way to wait until it becomes zero. This counter type is known as sync.WaitGroup, and the code below shows how to use it:

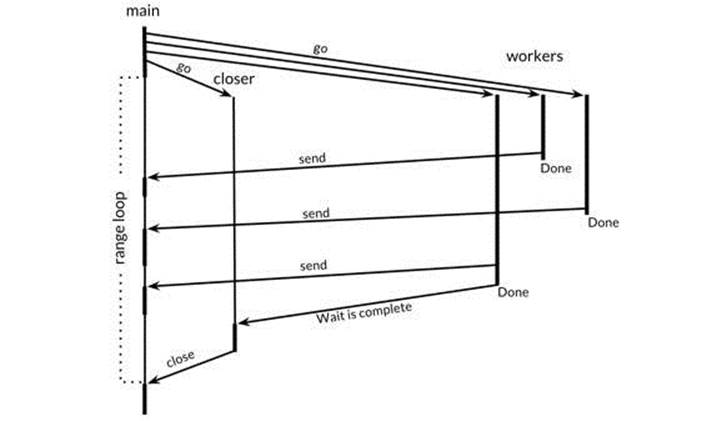

// makeThumbnails6 makes thumbnails for each file received from the channel.

// It returns the number of bytes occupied by the files it creates.

func makeThumbnails6(filenames <-chan string) int64 {

sizes := make(chan int64)

var wg sync.WaitGroup // number of working goroutines

for f := range filenames {

wg.Add(1)

// worker

go func(f string) {

defer wg.Done()

thumb, err := thumbnail.ImageFile(f)

if err != nil {

log.Println(err)

return

}

info, _ := os.Stat(thumb) // OK to ignore error

sizes <- info.Size()

}(f)

}

// closer

go func() {

wg.Wait()

close(sizes)

}()

var total int64

for size := range sizes {

total += size

}

return total

}

Note the asymmetry in the Add and Done methods. Add, which increments the counter, must be called before the worker goroutine starts, not within it; otherwise we would not be sure that the Add happens before the “closer” goroutine calls Wait. Also, Add takes a parameter, but Donedoes not; it’s equivalent to Add(-1). We use defer to ensure that the counter is decremented even in the error case. The structure of the code above is a common and idiomatic pattern for looping in parallel when we don’t know the number of iterations.

The sizes channel carries each file size back to the main goroutine, which receives them using a range loop and computes the sum. Observe how we create a closer goroutine that waits for the workers to finish before closing the sizes channel. These two operations, wait and close, must be concurrent with the loop over sizes. Consider the alternatives: if the wait operation were placed in the main goroutine before the loop, it would never end, and if placed after the loop, it would be unreachable since with nothing closing the channel, the loop would never terminate.

Figure 8.5. The sequence of events in makeThumbnails6.

Figure 8.5 illustrates the sequence of events in the makeThumbnails6 function. The vertical lines represent goroutines. The thin segments indicate sleep, the thick segments activity. The diagonal arrows indicate events that synchronize one goroutine with another. Time flows down. Notice how the main goroutine spends most of its time in the range loop asleep, waiting for a worker to send a value or the closer to close the channel.

Exercise 8.4: Modify the reverb2 server to use a sync.WaitGroup per connection to count the number of active echo goroutines. When it falls to zero, close the write half of the TCP connection as described in Exercise 8.3. Verify that your modified netcat3 client from that exercise waits for the final echoes of multiple concurrent shouts, even after the standard input has been closed.

Exercise 8.5: Take an existing CPU-bound sequential program, such as the Mandelbrot program of Section 3.3 or the 3-D surface computation of Section 3.2, and execute its main loop in parallel using channels for communication. How much faster does it run on a multiprocessor machine? What is the optimal number of goroutines to use?

8.6 Example: Concurrent Web Crawler

In Section 5.6, we made a simple web crawler that explored the link graph of the web in breadth-first order. In this section, we’ll make it concurrent so that independent calls to crawl can exploit the I/O parallelism available in the web. The crawl function remains exactly as it was ingopl.io/ch5/findlinks3:

gopl.io/ch8/crawl1

func crawl(url string) []string {

fmt.Println(url)

list, err := links.Extract(url)

if err != nil {

log.Print(err)

}

return list

}

The main function resembles breadthFirst (§5.6). As before, a worklist records the queue of items that need processing, each item being a list of URLs to crawl, but this time, instead of representing the queue using a slice, we use a channel. Each call to crawl occurs in its own goroutine and sends the links it discovers back to the worklist.

func main() {

worklist := make(chan []string)

// Start with the command-line arguments.

go func() { worklist <- os.Args[1:] }()

// Crawl the web concurrently.

seen := make(map[string]bool)

for list := range worklist {

for _, link := range list {

if !seen[link] {

seen[link] = true

go func(link string) {

worklist <- crawl(link)

}(link)

}

}

}

}

Notice that the crawl goroutine takes link as an explicit parameter to avoid the problem of loop variable capture we first saw in Section 5.6.1. Also notice that the initial send of the command-line arguments to the worklist must run in its own goroutine to avoid deadlock, a stuck situation in which both the main goroutine and a crawler goroutine attempt to send to each other while neither is receiving. An alternative solution would be to use a buffered channel.

The crawler is now highly concurrent and prints a storm of URLs, but it has two problems. The first problem manifests itself as error messages in the log after a few seconds of operation:

$ go build gopl.io/ch8/crawl1

$ ./crawl1 http://gopl.io/

http://gopl.io/

https://golang.org/help/

https://golang.org/doc/

https://golang.org/blog/

...

2015/07/15 18:22:12 Get ...: dial tcp: lookup blog.golang.org: no such host

2015/07/15 18:22:12 Get ...: dial tcp 23.21.222.120:443: socket:

too many open files

...

The initial error message is a surprising report of a DNS lookup failure for a reliable domain. The subsequent error message reveals the cause: the program created so many network connections at once that it exceeded the per-process limit on the number of open files, causing operations such as DNS lookups and calls to net.Dial to start failing.

The program is too parallel. Unbounded parallelism is rarely a good idea since there is always a limiting factor in the system, such as the number of CPU cores for compute-bound workloads, the number of spindles and heads for local disk I/O operations, the bandwidth of the network for streaming downloads, or the serving capacity of a web service. The solution is to limit the number of parallel uses of the resource to match the level of parallelism that is available. A simple way to do that in our example is to ensure that no more than n calls to links.Extract are active at once, where n is comfortably less than the file descriptor limit—20, say. This is analogous to the way a doorman at a crowded nightclub admits a guest only when some other guest leaves.

We can limit parallelism using a buffered channel of capacity n to model a concurrency primitive called a counting semaphore. Conceptually, each of the n vacant slots in the channel buffer represents a token entitling the holder to proceed. Sending a value into the channel acquires a token, and receiving a value from the channel releases a token, creating a new vacant slot. This ensures that at most n sends can occur without an intervening receive. (Although it might be more intuitive to treat filled slots in the channel buffer as tokens, using vacant slots avoids the need to fill the channel buffer after creating it.) Since the channel element type is not important, we’ll use struct{}, which has size zero.

Let’s rewrite the crawl function so that the call to links.Extract is bracketed by operations to acquire and release a token, thus ensuring that at most 20 calls to it are active at one time. It’s good practice to keep the semaphore operations as close as possible to the I/O operation they regulate.

gopl.io/ch8/crawl2

// tokens is a counting semaphore used to

// enforce a limit of 20 concurrent requests.

var tokens = make(chan struct{}, 20)

func crawl(url string) []string {

fmt.Println(url)

tokens <- struct{}{} // acquire a token

list, err := links.Extract(url)

<-tokens // release the token

if err != nil {

log.Print(err)

}

return list

}

The second problem is that the program never terminates, even when it has discovered all the links reachable from the initial URLs. (Of course, you’re unlikely to notice this problem unless you choose the initial URLs carefully or implement the depth-limiting feature of Exercise 8.6.) For the program to terminate, we need to break out of the main loop when the worklist is empty and no crawl goroutines are active.

func main() {

worklist := make(chan []string)

var n int // number of pending sends to worklist

// Start with the command-line arguments.

n++

go func() { worklist <- os.Args[1:] }()

// Crawl the web concurrently.

seen := make(map[string]bool)

for ; n > 0; n-- {

list := <-worklist

for _, link := range list {

if !seen[link] {

seen[link] = true

n++

go func(link string) {

worklist <- crawl(link)

}(link)

}

}

}

}

In this version, the counter n keeps track of the number of sends to the worklist that are yet to occur. Each time we know that an item needs to be sent to the worklist, we increment n, once before we send the initial command-line arguments, and again each time we start a crawler goroutine. The main loop terminates when n falls to zero, since there is no more work to be done.

Now the concurrent crawler runs about 20 times faster than the breadth-first crawler from Section 5.6, without errors, and terminates correctly if it should complete its task.

The program below shows an alternative solution to the problem of excessive concurrency. This version uses the original crawl function that has no counting semaphore, but calls it from one of 20 long-lived crawler goroutines, thus ensuring that at most 20 HTTP requests are active concurrently.

gopl.io/ch8/crawl3

func main() {

worklist := make(chan []string) // lists of URLs, may have duplicates

unseenLinks := make(chan string) // de-duplicated URLs

// Add command-line arguments to worklist.

go func() { worklist <- os.Args[1:] }()

// Create 20 crawler goroutines to fetch each unseen link.

for i := 0; i < 20; i++ {

go func() {

for link := range unseenLinks {

foundLinks := crawl(link)

go func() { worklist <- foundLinks }()

}

}()

}

// The main goroutine de-duplicates worklist items

// and sends the unseen ones to the crawlers.

seen := make(map[string]bool)

for list := range worklist {

for _, link := range list {

if !seen[link] {

seen[link] = true

unseenLinks <- link

}

}

}

}

The crawler goroutines are all fed by the same channel, unseenLinks. The main goroutine is responsible for de-duplicating items it receives from the worklist, and then sending each unseen one over the unseenLinks channel to a crawler goroutine.

The seen map is confined within the main goroutine; that is, it can be accessed only by that goroutine. Like other forms of information hiding, confinement helps us reason about the correctness of a program. For example, local variables cannot be mentioned by name from outside the function in which they are declared; variables that do not escape (§2.3.4) from a function cannot be accessed from outside that function; and encapsulated fields of an object cannot be accessed except by the methods of that object. In all cases, information hiding helps to limit unintended interactions between parts of the program.

Links found by crawl are sent to the worklist from a dedicated goroutine to avoid deadlock.

To save space, we have not addressed the problem of termination in this example.

Exercise 8.6: Add depth-limiting to the concurrent crawler. That is, if the user sets -depth=3, then only URLs reachable by at most three links will be fetched.

Exercise 8.7: Write a concurrent program that creates a local mirror of a web site, fetching each reachable page and writing it to a directory on the local disk. Only pages within the original domain (for instance, golang.org) should be fetched. URLs within mirrored pages should be altered as needed so that they refer to the mirrored page, not the original.

8.7 Multiplexing with select

The program below does the countdown for a rocket launch. The time.Tick function returns a channel on which it sends events periodically, acting like a metronome. The value of each event is a timestamp, but it is rarely as interesting as the fact of its delivery.

gopl.io/ch8/countdown1

func main() {

fmt.Println("Commencing countdown.")

tick := time.Tick(1 * time.Second)

for countdown := 10; countdown > 0; countdown-- {

fmt.Println(countdown)

<-tick

}

launch()

}

Now let’s add the ability to abort the launch sequence by pressing the return key during the countdown. First, we start a goroutine that tries to read a single byte from the standard input and, if it succeeds, sends a value on a channel called abort.

gopl.io/ch8/countdown2

abort := make(chan struct{})

go func() {

os.Stdin.Read(make([]byte, 1)) // read a single byte

abort <- struct{}{}

}()

Now each iteration of the countdown loop needs to wait for an event to arrive on one of the two channels: the ticker channel if everything is fine (“nominal” in NASA jargon) or an abort event if there was an “anomaly.” We can’t just receive from each channel because whichever operation we try first will block until completion. We need to multiplex these operations, and to do that, we need a select statement.

select {

case <-ch1:

// ...

case x := <-ch2:

// ...use x...

case ch3 <- y:

// ...

default:

// ...

}

The general form of a select statement is shown above. Like a switch statement, it has a number of cases and an optional default. Each case specifies a communication (a send or receive operation on some channel) and an associated block of statements. A receive expression may appear on its own, as in the first case, or within a short variable declaration, as in the second case; the second form lets you refer to the received value.

A select waits until a communication for some case is ready to proceed. It then performs that communication and executes the case’s associated statements; the other communications do not happen. A select with no cases, select{}, waits forever.

Let’s return to our rocket launch program. The time.After function immediately returns a channel, and starts a new goroutine that sends a single value on that channel after the specified time. The select statement below waits until the first of two events arrives, either an abort event or the event indicating that 10 seconds have elapsed. If 10 seconds go by with no abort, the launch proceeds.

func main() {

// ...create abort channel...

fmt.Println("Commencing countdown. Press return to abort.")

select {

case <-time.After(10 * time.Second):

// Do nothing.

case <-abort:

fmt.Println("Launch aborted!")

return

}

launch()

}

The example below is more subtle. The channel ch, whose buffer size is 1, is alternately empty then full, so only one of the cases can proceed, either the send when i is even, or the receive when i is odd. It always prints 0 2 4 6 8.

ch := make(chan int, 1)

for i := 0; i < 10; i++ {

select {

case x := <-ch:

fmt.Println(x) // "0" "2" "4" "6" "8"

case ch <- i:

}

}

If multiple cases are ready, select picks one at random, which ensures that every channel has an equal chance of being selected. Increasing the buffer size of the previous example makes its output nondeterministic, because when the buffer is neither full nor empty, the select statement figuratively tosses a coin.

Let’s make our launch program print the countdown. The select statement below causes each iteration of the loop to wait up to 1 second for an abort, but no longer.

gopl.io/ch8/countdown3

func main() {

// ...create abort channel...

fmt.Println("Commencing countdown. Press return to abort.")

tick := time.Tick(1 * time.Second)

for countdown := 10; countdown > 0; countdown-- {

fmt.Println(countdown)

select {

case <-tick:

// Do nothing.

case <-abort:

fmt.Println("Launch aborted!")

return

}

}

launch()

}

The time.Tick function behaves as if it creates a goroutine that calls time.Sleep in a loop, sending an event each time it wakes up. When the countdown function above returns, it stops receiving events from tick, but the ticker goroutine is still there, trying in vain to send on a channel from which no goroutine is receiving—a goroutine leak (§8.4.4).

The Tick function is convenient, but it’s appropriate only when the ticks will be needed throughout the lifetime of the application. Otherwise, we should use this pattern:

ticker := time.NewTicker(1 * time.Second)

<-ticker.C // receive from the ticker's channel

ticker.Stop() // cause the ticker's goroutine to terminate

Sometimes we want to try to send or receive on a channel but avoid blocking if the channel is not ready—a non-blocking communication. A select statement can do that too. A select may have a default, which specifies what to do when none of the other communications can proceed immediately.

The select statement below receives a value from the abort channel if there is one to receive; otherwise it does nothing. This is a non-blocking receive operation; doing it repeatedly is called polling a channel.

select {

case <-abort:

fmt.Printf("Launch aborted!\n")

return

default:

// do nothing

}

The zero value for a channel is nil. Perhaps surprisingly, nil channels are sometimes useful. Because send and receive operations on a nil channel block forever, a case in a select statement whose channel is nil is never selected. This lets us use nil to enable or disable cases that correspond to features like handling timeouts or cancellation, responding to other input events, or emitting output. We’ll see an example in the next section.

Exercise 8.8: Using a select statement, add a timeout to the echo server from Section 8.3 so that it disconnects any client that shouts nothing within 10 seconds.

8.8 Example: Concurrent Directory Traversal

In this section, we’ll build a program that reports the disk usage of one or more directories specified on the command line, like the Unix du command. Most of its work is done by the walkDir function below, which enumerates the entries of the directory dir using the dirents helper function.

gopl.io/ch8/du1

// walkDir recursively walks the file tree rooted at dir

// and sends the size of each found file on fileSizes.

func walkDir(dir string, fileSizes chan<- int64) {

for _, entry := range dirents(dir) {

if entry.IsDir() {

subdir := filepath.Join(dir, entry.Name())

walkDir(subdir, fileSizes)

} else {

fileSizes <- entry.Size()

}

}

}

// dirents returns the entries of directory dir.

func dirents(dir string) []os.FileInfo {

entries, err := ioutil.ReadDir(dir)

if err != nil {

fmt.Fprintf(os.Stderr, "du1: %v\n", err)

return nil

}

return entries

}

The ioutil.ReadDir function returns a slice of os.FileInfo—the same information that a call to os.Stat returns for a single file. For each subdirectory, walkDir recursively calls itself, and for each file, walkDir sends a message on the fileSizes channel. The message is the size of the file in bytes.

The main function, shown below, uses two goroutines. The background goroutine calls walkDir for each directory specified on the command line and finally closes the fileSizes channel. The main goroutine computes the sum of the file sizes it receives from the channel and finally prints the total.

// The du1 command computes the disk usage of the files in a directory.

package main

import (

"flag"

"fmt"

"io/ioutil"

"os"

"path/filepath"

)

func main() {

// Determine the initial directories.

flag.Parse()

roots := flag.Args()

if len(roots) == 0 {

roots = []string{"."}

}

// Traverse the file tree.

fileSizes := make(chan int64)

go func() {

for _, root := range roots {

walkDir(root, fileSizes)

}

close(fileSizes)

}()

// Print the results.

var nfiles, nbytes int64

for size := range fileSizes {

nfiles++

nbytes += size

}

printDiskUsage(nfiles, nbytes)

}

func printDiskUsage(nfiles, nbytes int64) {

fmt.Printf("%d files %.1f GB\n", nfiles, float64(nbytes)/1e9)

}

This program pauses for a long while before printing its result:

$ go build gopl.io/ch8/du1

$ ./du1 $HOME /usr /bin /etc

213201 files 62.7 GB

The program would be nicer if it kept us informed of its progress. However, simply moving the printDiskUsage call into the loop would cause it to print thousands of lines of output.

The variant of du below prints the totals periodically, but only if the -v flag is specified since not all users will want to see progress messages. The background goroutine that loops over roots remains unchanged. The main goroutine now uses a ticker to generate events every 500ms, and a select statement to wait for either a file size message, in which case it updates the totals, or a tick event, in which case it prints the current totals. If the -v flag is not specified, the tick channel remains nil, and its case in the select is effectively disabled.

gopl.io/ch8/du2

var verbose = flag.Bool("v", false, "show verbose progress messages")

func main() {

// ...start background goroutine...

// Print the results periodically.

var tick <-chan time.Time

if *verbose {

tick = time.Tick(500 * time.Millisecond)

}

var nfiles, nbytes int64

loop:

for {

select {

case size, ok := <-fileSizes:

if !ok {

break loop // fileSizes was closed

}

nfiles++

nbytes += size

case <-tick:

printDiskUsage(nfiles, nbytes)

}

}

printDiskUsage(nfiles, nbytes) // final totals

}

Since the program no longer uses a range loop, the first select case must explicitly test whether the fileSizes channel has been closed, using the two-result form of receive operation. If the channel has been closed, the program breaks out of the loop. The labeled break statement breaks out of both the select and the for loop; an unlabeled break would break out of only the select, causing the loop to begin the next iteration.

The program now gives us a leisurely stream of updates:

$ go build gopl.io/ch8/du2

$ ./du2 -v $HOME /usr /bin /etc

28608 files 8.3 GB

54147 files 10.3 GB

93591 files 15.1 GB

127169 files 52.9 GB

175931 files 62.2 GB

213201 files 62.7 GB

However, it still takes too long to finish. There’s no reason why all the calls to walkDir can’t be done concurrently, thereby exploiting parallelism in the disk system. The third version of du, below, creates a new goroutine for each call to walkDir. It uses a sync.WaitGroup (§8.5) to count the number of calls to walkDir that are still active, and a closer goroutine to close the fileSizes channel when the counter drops to zero.

gopl.io/ch8/du3

func main() {

// ...determine roots...

// Traverse each root of the file tree in parallel.

fileSizes := make(chan int64)

var n sync.WaitGroup

for _, root := range roots {

n.Add(1)

go walkDir(root, &n, fileSizes)

}

go func() {

n.Wait()

close(fileSizes)

}()

// ...select loop...

}

func walkDir(dir string, n *sync.WaitGroup, fileSizes chan<- int64) {

defer n.Done()

for _, entry := range dirents(dir) {

if entry.IsDir() {

n.Add(1)

subdir := filepath.Join(dir, entry.Name())

go walkDir(subdir, n, fileSizes)

} else {

fileSizes <- entry.Size()

}

}

}

Since this program creates many thousands of goroutines at its peak, we have to change dirents to use a counting semaphore to prevent it from opening too many files at once, just as we did for the web crawler in Section 8.6:

// sema is a counting semaphore for limiting concurrency in dirents.

var sema = make(chan struct{}, 20)

// dirents returns the entries of directory dir.

func dirents(dir string) []os.FileInfo {

sema <- struct{}{} // acquire token

defer func() { <-sema }() // release token

// ...

This version runs several times faster than the previous one, though there is a lot of variability from system to system.

Exercise 8.9: Write a version of du that computes and periodically displays separate totals for each of the root directories.

8.9 Cancellation

Sometimes we need to instruct a goroutine to stop what it is doing, for example, in a web server performing a computation on behalf of a client that has disconnected.

There is no way for one goroutine to terminate another directly, since that would leave all its shared variables in undefined states. In the rocket launch program (§8.7) we sent a single value on a channel named abort, which the countdown goroutine interpreted as a request to stop itself. But what if we need to cancel two goroutines, or an arbitrary number?

One possibility might be to send as many events on the abort channel as there are goroutines to cancel. If some of the goroutines have already terminated themselves, however, our count will be too large, and our sends will get stuck. On the other hand, if those goroutines have spawned other goroutines, our count will be too small, and some goroutines will remain unaware of the cancellation. In general, it’s hard to know how many goroutines are working on our behalf at any given moment. Moreover, when a goroutine receives a value from the abort channel, it consumes that value so that other goroutines won’t see it. For cancellation, what we need is a reliable mechanism to broadcast an event over a channel so that many goroutines can see it as it occurs and can later see that it has occurred.

Recall that after a channel has been closed and drained of all sent values, subsequent receive operations proceed immediately, yielding zero values. We can exploit this to create a broadcast mechanism: don’t send a value on the channel, close it.

We can add cancellation to the du program from the previous section with a few simple changes. First, we create a cancellation channel on which no values are ever sent, but whose closure indicates that it is time for the program to stop what it is doing. We also define a utility function,cancelled, that checks or polls the cancellation state at the instant it is called.

gopl.io/ch8/du4

var done = make(chan struct{})

func cancelled() bool {

select {

case <-done:

return true

default:

return false

}

}

Next, we create a goroutine that will read from the standard input, which is typically connected to the terminal. As soon as any input is read (for instance, the user presses the return key), this goroutine broadcasts the cancellation by closing the done channel.

// Cancel traversal when input is detected.

go func() {

os.Stdin.Read(make([]byte, 1)) // read a single byte

close(done)

}()

Now we need to make our goroutines respond to the cancellation. In the main goroutine, we add a third case to the select statement that tries to receive from the done channel. The function returns if this case is ever selected, but before it returns it must first drain the fileSizes channel, discarding all values until the channel is closed. It does this to ensure that any active calls to walkDir can run to completion without getting stuck sending to fileSizes.

for {

select {

case <-done:

// Drain fileSizes to allow existing goroutines to finish.

for range fileSizes {

// Do nothing.

}

return

case size, ok := <-fileSizes:

// ...

}

}

The walkDir goroutine polls the cancellation status when it begins, and returns without doing anything if the status is set. This turns all goroutines created after cancellation into no-ops:

func walkDir(dir string, n *sync.WaitGroup, fileSizes chan<- int64) {

defer n.Done()

if cancelled() {

return

}

for _, entry := range dirents(dir) {

// ...

}

}

It might be profitable to poll the cancellation status again within walkDir’s loop, to avoid creating goroutines after the cancellation event. Cancellation involves a trade-off; a quicker response often requires more intrusive changes to program logic. Ensuring that no expensive operations ever occur after the cancellation event may require updating many places in your code, but often most of the benefit can be obtained by checking for cancellation in a few important places.

A little profiling of this program revealed that the bottleneck was the acquisition of a semaphore token in dirents. The select below makes this operation cancellable and reduces the typical cancellation latency of the program from hundreds of milliseconds to tens:

func dirents(dir string) []os.FileInfo {

select {

case sema <- struct{}{}: // acquire token

case <-done:

return nil // cancelled

}

defer func() { <-sema }() // release token

// ...read directory...

}

Now, when cancellation occurs, all the background goroutines quickly stop and the main function returns. Of course, when main returns, a program exits, so it can be hard to tell a main function that cleans up after itself from one that does not. There’s a handy trick we can use during testing: if instead of returning from main in the event of cancellation, we execute a call to panic, then the runtime will dump the stack of every goroutine in the program. If the main goroutine is the only one left, then it has cleaned up after itself. But if other goroutines remain, they may not have been properly cancelled, or perhaps they have been cancelled but the cancellation takes time; a little investigation may be worthwhile. The panic dump often contains sufficient information to distinguish these cases.

Exercise 8.10: HTTP requests may be cancelled by closing the optional Cancel channel in the http.Request struct. Modify the web crawler of Section 8.6 to support cancellation.

Hint: the http.Get convenience function does not give you an opportunity to customize a Request. Instead, create the request using http.NewRequest, set its Cancel field, then perform the request by calling http.DefaultClient.Do(req).

Exercise 8.11: Following the approach of mirroredQuery in Section 8.4.4, implement a variant of fetch that requests several URLs concurrently. As soon as the first response arrives, cancel the other requests.

8.10 Example: Chat Server

We’ll finish this chapter with a chat server that lets several users broadcast textual messages to each other. There are four kinds of goroutine in this program. There is one instance apiece of the main and broadcaster goroutines, and for each client connection there is one handleConnand one clientWriter goroutine. The broadcaster is a good illustration of how select is used, since it has to respond to three different kinds of messages.

The job of the main goroutine, shown below, is to listen for and accept incoming network connections from clients. For each one, it creates a new handleConn goroutine, just as in the concurrent echo server we saw at the start of this chapter.

gopl.io/ch8/chat

func main() {

listener, err := net.Listen("tcp", "localhost:8000")

if err != nil {

log.Fatal(err)

}

go broadcaster()

for {

conn, err := listener.Accept()

if err != nil {

log.Print(err)

continue

}

go handleConn(conn)

}

}

Next is the broadcaster. Its local variable clients records the current set of connected clients. The only information recorded about each client is the identity of its outgoing message channel, about which more later.

type client chan<- string // an outgoing message channel

var (

entering = make(chan client)

leaving = make(chan client)

messages = make(chan string) // all incoming client messages

)

func broadcaster() {

clients := make(map[client]bool) // all connected clients

for {

select {

case msg := <-messages:

// Broadcast incoming message to all

// clients' outgoing message channels.

for cli := range clients {

cli <- msg

}

case cli := <-entering:

clients[cli] = true

case cli := <-leaving:

delete(clients, cli)

close(cli)

}

}

}

The broadcaster listens on the global entering and leaving channels for announcements of arriving and departing clients. When it receives one of these events, it updates the clients set, and if the event was a departure, it closes the client’s outgoing message channel. The broadcaster also listens for events on the global messages channel, to which each client sends all its incoming messages. When the broadcaster receives one of these events, it broadcasts the message to every connected client.

Now let’s look at the per-client goroutines. The handleConn function creates a new outgoing message channel for its client and announces the arrival of this client to the broadcaster over the entering channel. Then it reads every line of text from the client, sending each line to the broadcaster over the global incoming message channel, prefixing each message with the identity of its sender. Once there is nothing more to read from the client, handleConn announces the departure of the client over the leaving channel and closes the connection.

func handleConn(conn net.Conn) {

ch := make(chan string) // outgoing client messages

go clientWriter(conn, ch)

who := conn.RemoteAddr().String()

ch <- "You are " + who

messages <- who + " has arrived"

entering <- ch

input := bufio.NewScanner(conn)

for input.Scan() {

messages <- who + ": " + input.Text()

}

// NOTE: ignoring potential errors from input.Err()

leaving <- ch

messages <- who + " has left"

conn.Close()

}

func clientWriter(conn net.Conn, ch <-chan string) {

for msg := range ch {

fmt.Fprintln(conn, msg) // NOTE: ignoring network errors

}

}

In addition, handleConn creates a clientWriter goroutine for each client that receives messages broadcast to the client’s outgoing message channel and writes them to the client’s network connection. The client writer’s loop terminates when the broadcaster closes the channel after receiving a leaving notification.

The display below shows the server in action with two clients in separate windows on the same computer, using netcat to chat:

$ go build gopl.io/ch8/chat

$ go build gopl.io/ch8/netcat3

$ ./chat &

$ ./netcat3

You are 127.0.0.1:64208 $ ./netcat3

127.0.0.1:64211 has arrived You are 127.0.0.1:64211

Hi!

127.0.0.1:64208: Hi! 127.0.0.1:64208: Hi!

Hi yourself.

127.0.0.1:64211: Hi yourself. 127.0.0.1:64211: Hi yourself.

^C

127.0.0.1:64208 has left

$ ./netcat3

You are 127.0.0.1:64216 127.0.0.1:64216 has arrived

Welcome.

127.0.0.1:64211: Welcome. 127.0.0.1:64211: Welcome.

^C

127.0.0.1:64211 has left