Learning Python (2013)

Part I. Getting Started

Chapter 2. How Python Runs Programs

This chapter and the next take a quick look at program execution—how you launch code, and how Python runs it. In this chapter, we’ll study how the Python interpreter executes programs in general. Chapter 3 will then show you how to get your own programs up and running.

Startup details are inherently platform-specific, and some of the material in these two chapters may not apply to the platform you work on, so more advanced readers should feel free to skip parts not relevant to their intended use. Likewise, readers who have used similar tools in the past and prefer to get to the meat of the language quickly may want to file some of these chapters away as “for future reference.” For the rest of us, let’s take a brief look at the way that Python will run our code, before we learn how to write it.

Introducing the Python Interpreter

So far, I’ve mostly been talking about Python as a programming language. But, as currently implemented, it’s also a software package called an interpreter. An interpreter is a kind of program that executes other programs. When you write a Python program, the Python interpreter reads your program and carries out the instructions it contains. In effect, the interpreter is a layer of software logic between your code and the computer hardware on your machine.

When the Python package is installed on your machine, it generates a number of components—minimally, an interpreter and a support library. Depending on how you use it, the Python interpreter may take the form of an executable program, or a set of libraries linked into another program. Depending on which flavor of Python you run, the interpreter itself may be implemented as a C program, a set of Java classes, or something else. Whatever form it takes, the Python code you write must always be run by this interpreter. And to enable that, you must install a Python interpreter on your computer.

Python installation details vary by platform and are covered in more depth in Appendix A. In short:

§ Windows users fetch and run a self-installing executable file that puts Python on their machines. Simply double-click and say Yes or Next at all prompts.

§ Linux and Mac OS X users probably already have a usable Python preinstalled on their computers—it’s a standard component on these platforms today.

§ Some Linux and Mac OS X users (and most Unix users) compile Python from its full source code distribution package.

§ Linux users can also find RPM files, and Mac OS X users can find various Mac-specific installation packages.

§ Other platforms have installation techniques relevant to those platforms. For instance, Python is available on cell phones, tablets, game consoles, and iPods, but installation details vary widely.

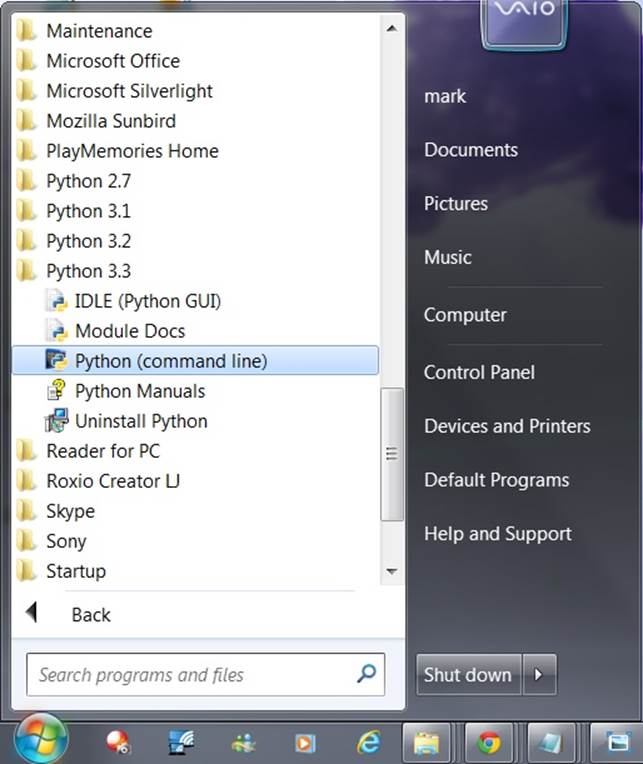

Python itself may be fetched from the downloads page on its main website, http://www.python.org. It may also be found through various other distribution channels. Keep in mind that you should always check to see whether Python is already present before installing it. If you’re working on Windows 7 and earlier, you’ll usually find Python in the Start menu, as captured in Figure 2-1; we’ll discuss the menu options shown here in the next chapter. On Unix and Linux, Python probably lives in your /usr directory tree.

Figure 2-1. When installed on Windows 7 and earlier, this is how Python shows up in your Start button menu. This can vary across releases, but IDLE starts a development GUI, and Python starts a simple interactive session. Also here are the standard manuals and the PyDoc documentation engine (Module Docs). See Chapter 3 and Appendix A for pointers on Windows 8 and other platforms.

Because installation details are so platform-specific, we’ll postpone the rest of this story here. For more details on the installation process, consult Appendix A. For the purposes of this chapter and the next, I’ll assume that you’ve got Python ready to go.

Program Execution

What it means to write and run a Python script depends on whether you look at these tasks as a programmer, or as a Python interpreter. Both views offer important perspectives on Python programming.

The Programmer’s View

In its simplest form, a Python program is just a text file containing Python statements. For example, the following file, named script0.py, is one of the simplest Python scripts I could dream up, but it passes for a fully functional Python program:

print('hello world')

print(2 ** 100)

This file contains two Python print statements, which simply print a string (the text in quotes) and a numeric expression result (2 to the power 100) to the output stream. Don’t worry about the syntax of this code yet—for this chapter, we’re interested only in getting it to run. I’ll explain theprint statement, and why you can raise 2 to the power 100 in Python without overflowing, in the next parts of this book.

You can create such a file of statements with any text editor you like. By convention, Python program files are given names that end in .py; technically, this naming scheme is required only for files that are “imported”—a term clarified in the next chapter—but most Python files have .pynames for consistency.

After you’ve typed these statements into a text file, you must tell Python to execute the file—which simply means to run all the statements in the file from top to bottom, one after another. As you’ll see in the next chapter, you can launch Python program files by shell command lines, by clicking their icons, from within IDEs, and with other standard techniques. If all goes well, when you execute the file, you’ll see the results of the two print statements show up somewhere on your computer—by default, usually in the same window you were in when you ran the program:

hello world

1267650600228229401496703205376

For example, here’s what happened when I ran this script from a Command Prompt window’s command line on a Windows laptop, to make sure it didn’t have any silly typos:

C:\code> python script0.py

hello world

1267650600228229401496703205376

See Chapter 3 for the full story on this process, especially if you’re new to programming; we’ll get into all the gory details of writing and launching programs there. For our purposes here, we’ve just run a Python script that prints a string and a number. We probably won’t win any programming awards with this code, but it’s enough to capture the basics of program execution.

Python’s View

The brief description in the prior section is fairly standard for scripting languages, and it’s usually all that most Python programmers need to know. You type code into text files, and you run those files through the interpreter. Under the hood, though, a bit more happens when you tell Python to “go.” Although knowledge of Python internals is not strictly required for Python programming, a basic understanding of the runtime structure of Python can help you grasp the bigger picture of program execution.

When you instruct Python to run your script, there are a few steps that Python carries out before your code actually starts crunching away. Specifically, it’s first compiled to something called “byte code” and then routed to something called a “virtual machine.”

Byte code compilation

Internally, and almost completely hidden from you, when you execute a program Python first compiles your source code (the statements in your file) into a format known as byte code. Compilation is simply a translation step, and byte code is a lower-level, platform-independent representation of your source code. Roughly, Python translates each of your source statements into a group of byte code instructions by decomposing them into individual steps. This byte code translation is performed to speed execution—byte code can be run much more quickly than the original source code statements in your text file.

You’ll notice that the prior paragraph said that this is almost completely hidden from you. If the Python process has write access on your machine, it will store the byte code of your programs in files that end with a .pyc extension (“.pyc” means compiled “.py” source). Prior to Python 3.2, you will see these files show up on your computer after you’ve run a few programs alongside the corresponding source code files—that is, in the same directories. For instance, you’ll notice a script.pyc after importing a script.py.

In 3.2 and later, Python instead saves its .pyc byte code files in a subdirectory named __pycache__ located in the directory where your source files reside, and in files whose names identify the Python version that created them (e.g., script.cpython-33.pyc). The new __pycache__ subdirectory helps to avoid clutter, and the new naming convention for byte code files prevents different Python versions installed on the same computer from overwriting each other’s saved byte code. We’ll study these byte code file models in more detail in Chapter 22, though they are automatic and irrelevant to most Python programs, and are free to vary among the alternative Python implementations described ahead.

In both models, Python saves byte code like this as a startup speed optimization. The next time you run your program, Python will load the .pyc files and skip the compilation step, as long as you haven’t changed your source code since the byte code was last saved, and aren’t running with a different Python than the one that created the byte code. It works like this:

§ Source changes: Python automatically checks the last-modified timestamps of source and byte code files to know when it must recompile—if you edit and resave your source code, byte code is automatically re-created the next time your program is run.

§ Python versions: Imports also check to see if the file must be recompiled because it was created by a different Python version, using either a “magic” version number in the byte code file itself in 3.2 and earlier, or the information present in byte code filenames in 3.2 and later.

The result is that both source code changes and differing Python version numbers will trigger a new byte code file. If Python cannot write the byte code files to your machine, your program still works—the byte code is generated in memory and simply discarded on program exit. However, because .pyc files speed startup time, you’ll want to make sure they are written for larger programs. Byte code files are also one way to ship Python programs—Python is happy to run a program if all it can find are .pyc files, even if the original .py source files are absent. (See Frozen Binariesfor another shipping option.)

Finally, keep in mind that byte code is saved in files only for files that are imported, not for the top-level files of a program that are only run as scripts (strictly speaking, it’s an import optimization). We’ll explore import basics in Chapter 3, and take a deeper look at imports in Part V. Moreover, a given file is only imported (and possibly compiled) once per program run, and byte code is also never saved for code typed at the interactive prompt—a programming mode we’ll learn about in Chapter 3.

The Python Virtual Machine (PVM)

Once your program has been compiled to byte code (or the byte code has been loaded from existing .pyc files), it is shipped off for execution to something generally known as the Python Virtual Machine (PVM, for the more acronym-inclined among you). The PVM sounds more impressive than it is; really, it’s not a separate program, and it need not be installed by itself. In fact, the PVM is just a big code loop that iterates through your byte code instructions, one by one, to carry out their operations. The PVM is the runtime engine of Python; it’s always present as part of the Python system, and it’s the component that truly runs your scripts. Technically, it’s just the last step of what is called the “Python interpreter.”

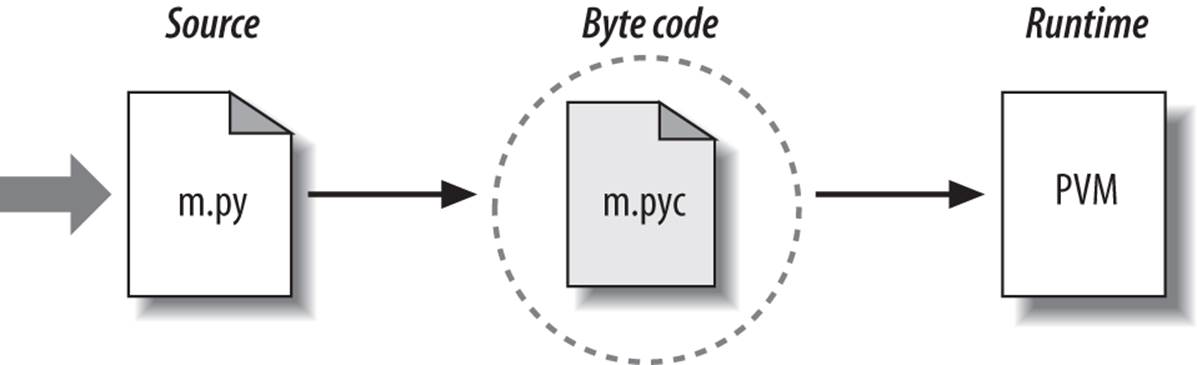

Figure 2-2 illustrates the runtime structure described here. Keep in mind that all of this complexity is deliberately hidden from Python programmers. Byte code compilation is automatic, and the PVM is just part of the Python system that you have installed on your machine. Again, programmers simply code and run files of statements, and Python handles the logistics of running them.

Figure 2-2. Python’s traditional runtime execution model: source code you type is translated to byte code, which is then run by the Python Virtual Machine. Your code is automatically compiled, but then it is interpreted.

Performance implications

Readers with a background in fully compiled languages such as C and C++ might notice a few differences in the Python model. For one thing, there is usually no build or “make” step in Python work: code runs immediately after it is written. For another, Python byte code is not binary machine code (e.g., instructions for an Intel or ARM chip). Byte code is a Python-specific representation.

This is why some Python code may not run as fast as C or C++ code, as described in Chapter 1—the PVM loop, not the CPU chip, still must interpret the byte code, and byte code instructions require more work than CPU instructions. On the other hand, unlike in classic interpreters, there is still an internal compile step—Python does not need to reanalyze and reparse each source statement’s text repeatedly. The net effect is that pure Python code runs at speeds somewhere between those of a traditional compiled language and a traditional interpreted language. See Chapter 1 for more on Python performance tradeoffs.

Development implications

Another ramification of Python’s execution model is that there is really no distinction between the development and execution environments. That is, the systems that compile and execute your source code are really one and the same. This similarity may have a bit more significance to readers with a background in traditional compiled languages, but in Python, the compiler is always present at runtime and is part of the system that runs programs.

This makes for a much more rapid development cycle. There is no need to precompile and link before execution may begin; simply type and run the code. This also adds a much more dynamic flavor to the language—it is possible, and often very convenient, for Python programs to construct and execute other Python programs at runtime. The eval and exec built-ins, for instance, accept and run strings containing Python program code. This structure is also why Python lends itself to product customization—because Python code can be changed on the fly, users can modify the Python parts of a system onsite without needing to have or compile the entire system’s code.

At a more fundamental level, keep in mind that all we really have in Python is runtime—there is no initial compile-time phase at all, and everything happens as the program is running. This even includes operations such as the creation of functions and classes and the linkage of modules. Such events occur before execution in more static languages, but happen as programs execute in Python. As we’ll see, this makes for a much more dynamic programming experience than that to which some readers may be accustomed.

Execution Model Variations

Now that we’ve studied the internal execution flow described in the prior section, I should note that it reflects the standard implementation of Python today but is not really a requirement of the Python language itself. Because of that, the execution model is prone to changing with time. In fact, there are already a few systems that modify the picture in Figure 2-2 somewhat. Before moving on, let’s briefly explore the most prominent of these variations.

Python Implementation Alternatives

Strictly speaking, as this book edition is being written, there are at least five implementations of the Python language—CPython, Jython, IronPython, Stackless, and PyPy. Although there is much cross-fertilization of ideas and work between these Pythons, each is a separately installed software system, with its own developers and user base. Other potential candidates here include the Cython and Shed Skin systems, but they are discussed later as optimization tools because they do not implement the standard Python language (the former is a Python/C mix, and the latter is implicitly statically typed).

In brief, CPython is the standard implementation, and the system that most readers will wish to use (if you’re not sure, this probably includes you). This is also the version used in this book, though the core Python language presented here is almost entirely the same in the alternatives. All the other Python implementations have specific purposes and roles, though they can often serve in most of CPython’s capacities too. All implement the same Python language but execute programs in different ways.

For example, PyPy is a drop-in replacement for CPython, which can run most programs much quicker. Similarly, Jython and IronPython are completely independent implementations of Python that compile Python source for different runtime architectures, to provide direct access to Java and .NET components. It is also possible to access Java and .NET software from standard CPython programs—JPype and Python for .NET systems, for instance, allow standard CPython code to call out to Java and .NET components. Jython and IronPython offer more complete solutions, by providing full implementations of the Python language.

Here’s a quick rundown on the most prominent Python implementations available today.

CPython: The standard

The original, and standard, implementation of Python is usually called CPython when you want to contrast it with the other options (and just plain “Python” otherwise). This name comes from the fact that it is coded in portable ANSI C language code. This is the Python that you fetch fromhttp://www.python.org, get with the ActivePython and Enthought distributions, and have automatically on most Linux and Mac OS X machines. If you’ve found a preinstalled version of Python on your machine, it’s probably CPython, unless your company or organization is using Python in more specialized ways.

Unless you want to script Java or .NET applications with Python or find the benefits of Stackless or PyPy compelling, you probably want to use the standard CPython system. Because it is the reference implementation of the language, it tends to run the fastest, be the most complete, and be more up-to-date and robust than the alternative systems. Figure 2-2 reflects CPython’s runtime architecture.

Jython: Python for Java

The Jython system (originally known as JPython) is an alternative implementation of the Python language, targeted for integration with the Java programming language. Jython consists of Java classes that compile Python source code to Java byte code and then route the resulting byte code to the Java Virtual Machine (JVM). Programmers still code Python statements in .py text files as usual; the Jython system essentially just replaces the rightmost two bubbles in Figure 2-2 with Java-based equivalents.

Jython’s goal is to allow Python code to script Java applications, much as CPython allows Python to script C and C++ components. Its integration with Java is remarkably seamless. Because Python code is translated to Java byte code, it looks and feels like a true Java program at runtime. Jython scripts can serve as web applets and servlets, build Java-based GUIs, and so on. Moreover, Jython includes integration support that allows Python code to import and use Java classes as though they were coded in Python, and Java code to run Python code as an embedded language. Because Jython is slower and less robust than CPython, though, it is usually seen as a tool of interest primarily to Java developers looking for a scripting language to serve as a frontend to Java code. See Jython’s website http://jython.org for more details.

IronPython: Python for .NET

A third implementation of Python, and newer than both CPython and Jython, IronPython is designed to allow Python programs to integrate with applications coded to work with Microsoft’s .NET Framework for Windows, as well as the Mono open source equivalent for Linux. .NET and its C# programming language runtime system are designed to be a language-neutral object communication layer, in the spirit of Microsoft’s earlier COM model. IronPython allows Python programs to act as both client and server components, gain accessibility both to and from other .NET languages, and leverage .NET technologies such as the Silverlight framework from their Python code.

By implementation, IronPython is very much like Jython (and, in fact, was developed by the same creator)—it replaces the last two bubbles in Figure 2-2 with equivalents for execution in the .NET environment. Also like Jython, IronPython has a special focus—it is primarily of interest to developers integrating Python with .NET components. Formerly developed by Microsoft and now an open source project, IronPython might also be able to take advantage of some important optimization tools for better performance. For more details, consult http://ironpython.net and other resources to be had with a web search.

Stackless: Python for concurrency

Still other schemes for running Python programs have more focused goals. For example, the Stackless Python system is an enhanced version and reimplementation of the standard CPython language oriented toward concurrency. Because it does not save state on the C language call stack, Stackless Python can make Python easier to port to small stack architectures, provides efficient multiprocessing options, and fosters novel programming structures such as coroutines.

Among other things, the microthreads that Stackless adds to Python are an efficient and lightweight alternative to Python’s standard multitasking tools such as threads and processes, and promise better program structure, more readable code, and increased programmer productivity. CCP Games, the creator of EVE Online, is a well-known Stackless Python user, and a compelling Python user success story in general. Try http://stackless.com for more information.

PyPy: Python for speed

The PyPy system is another standard CPython reimplementation, focused on performance. It provides a fast Python implementation with a JIT (just-in-time) compiler, provides tools for a “sandbox” model that can run untrusted code in a secure environment, and by default includes support for the prior section’s Stackless Python systems and its microthreads to support massive concurrency.

PyPy is the successor to the original Psyco JIT, described ahead, and subsumes it with a complete Python implementation built for speed. A JIT is really just an extension to the PVM—the rightmost bubble in Figure 2-2—that translates portions of your byte code all the way to binary machine code for faster execution. It does this as your program is running, not in a prerun compile step, and is able to created type-specific machine code for the dynamic Python language by keeping track of the data types of the objects your program processes. By replacing portions of your byte code this way, your program runs faster and faster as it is executing. In addition, some Python programs may also take up less memory under PyPy.

At this writing, PyPy supports Python 2.7 code (not yet 3.X) and runs on Intel x86 (IA-32) and x86_64 platforms (including Windows, Linux, and recent Macs), with ARM and PPC support under development. It runs most CPython code, though C extension modules must generally be recompiled, and PyPy has some minor but subtle language differences, including garbage collection semantics that obviate some common coding patterns. For instance, its non-reference-count scheme means that temporary files may not close and flush output buffers immediately, and may require manual close calls in some cases.

In return, your code may run much quicker. PyPy currently claims a 5.7X speedup over CPython across a range of benchmark programs (per http://speed.pypy.org/). In some cases, its ability to take advantage of dynamic optimization opportunities can make Python code as quick as C code, and occasionally faster. This is especially true for heavily algorithmic or numeric programs, which might otherwise be recoded in C.

For instance, in one simple benchmark we’ll see in Chapter 21, PyPy today clocks in at 10X faster than CPython 2.7, and 100X faster than CPython 3.X. Though other benchmarks will vary, such speedups may be a compelling advantage in many domains, perhaps even more so than leading-edge language features. Just as important, memory space is also optimized in PyPy—in the case of one posted benchmark, requiring 247 MB and completing in 10.3 seconds, compared to CPython’s 684 MB and 89 seconds.

PyPy’s tool chain is also general enough to support additional languages, including Pyrolog, a Prolog interpreter written in Python using the PyPy translator. Search for PyPy’s website for more. PyPy currently lives at http://pypy.org, though the usual web search may also prove fruitful over time. For an overview of its current performance, also see http://www.pypy.org/performance.html.

NOTE

Just after I wrote this, PyPy 2.0 was released in beta form, adding support for the ARM processor, and still a Python 2.X-only implementation. Per its 2.0 beta release notes:

“PyPy is a very compliant Python interpreter, almost a drop-in replacement for CPython 2.7.3. It’s fast due to its integrated tracing JIT compiler. This release supports x86 machines running Linux 32/64, Mac OS X 64 or Windows 32. It also supports ARM machines running Linux.”

The claims seem accurate. Using the timing tools we’ll study in Chapter 21, PyPy is often an order of magnitude (factor of 10) faster than CPython 2.X and 3.X on tests I’ve run, and sometimes even better. This is despite the fact that PyPy is a 32-bit build on my Windows test machine, while CPython is a faster 64-bit compile.

Naturally the only benchmark that truly matters is your own code, and there are cases where CPython wins the race; PyPy’s file iterators, for instance, may clock in slower today. Still, given PyPy’s focus on performance over language mutation, and especially its support for the numeric domain, many today see PyPy as an important path for Python. If you write CPU-intensive code, PyPy deserves your attention.

Execution Optimization Tools

CPython and most of the alternatives of the prior section all implement the Python language in similar ways: by compiling source code to byte code and executing the byte code on an appropriate virtual machine. Some systems, such as the Cython hybrid, the Shed Skin C++ translator, and the just-in-time compilers in PyPy and Psyco instead attempt to optimize the basic execution model. These systems are not required knowledge at this point in your Python career, but a quick look at their place in the execution model might help demystify the model in general.

Cython: A Python/C hybrid

The Cython system (based on work done by the Pyrex project) is a hybrid language that combines Python code with the ability to call C functions and use C type declarations for variables, parameters, and class attributes. Cython code can be compiled to C code that uses the Python/C API, which may then be compiled completely. Though not completely compatible with standard Python, Cython can be useful both for wrapping external C libraries and for coding efficient C extensions for Python. See http://cython.org for current status and details.

Shed Skin: A Python-to-C++ translator

Shed Skin is an emerging system that takes a different approach to Python program execution—it attempts to translate Python source code to C++ code, which your computer’s C++ compiler then compiles to machine code. As such, it represents a platform-neutral approach to running Python code.

Shed Skin is still being actively developed as I write these words. It currently supports Python 2.4 to 2.6 code, and it limits Python programs to an implicit statically typed constraint that is typical of most programs but is technically not normal Python, so we won’t go into further detail here. Initial results, though, show that it has the potential to outperform both standard Python and Psyco-like extensions in terms of execution speed. Search the Web for details on the project’s current status.

Psyco: The original just-in-time compiler

The Psyco system is not another Python implementation, but rather a component that extends the byte code execution model to make programs run faster. Today, Psyco is something of an ex-project: it is still available for separate download, but has fallen out of date with Python’s evolution, and is no longer actively maintained. Instead, its ideas have been incorporated into the more complete PyPy system described earlier. Still, the ongoing importance of the ideas Psyco explored makes them worth a quick look.

In terms of Figure 2-2, Psyco is an enhancement to the PVM that collects and uses type information while the program runs to translate portions of the program’s byte code all the way down to true binary machine code for faster execution. Psyco accomplishes this translation without requiring changes to the code or a separate compilation step during development.

Roughly, while your program runs, Psyco collects information about the kinds of objects being passed around; that information can be used to generate highly efficient machine code tailored for those object types. Once generated, the machine code then replaces the corresponding part of the original byte code to speed your program’s overall execution. The result is that with Psyco, your program becomes quicker over time as it runs. In ideal cases, some Python code may become as fast as compiled C code under Psyco.

Because this translation from byte code happens at program runtime, Psyco is known as a just-in-time compiler. Psyco is different from the JIT compilers some readers may have seen for the Java language, though. Really, Psyco is a specializing JIT compiler—it generates machine code tailored to the data types that your program actually uses. For example, if a part of your program uses different data types at different times, Psyco may generate a different version of machine code to support each different type combination.

Psyco was shown to speed some Python code dramatically. According to its web page, Psyco provides “2X to 100X speed-ups, typically 4X, with an unmodified Python interpreter and unmodified source code, just a dynamically loadable C extension module.” Of equal significance, the largest speedups are realized for algorithmic code written in pure Python—exactly the sort of code you might normally migrate to C to optimize. For more on Psyco, search the Web or see its successor—the PyPy project described previously.

Frozen Binaries

Sometimes when people ask for a “real” Python compiler, what they’re really seeking is simply a way to generate standalone binary executables from their Python programs. This is more a packaging and shipping idea than an execution-flow concept, but it’s somewhat related. With the help of third-party tools that you can fetch off the Web, it is possible to turn your Python programs into true executables, known as frozen binaries in the Python world. These programs can be run without requiring a Python installation.

Frozen binaries bundle together the byte code of your program files, along with the PVM (interpreter) and any Python support files your program needs, into a single package. There are some variations on this theme, but the end result can be a single binary executable program (e.g., an .exefile on Windows) that can easily be shipped to customers. In Figure 2-2, it is as though the two rightmost bubbles—byte code and PVM—are merged into a single component: a frozen binary file.

Today, a variety of systems are capable of generating frozen binaries, which vary in platforms and features: py2exe for Windows only, but with broad Windows support; PyInstaller, which is similar to py2exe but also works on Linux and Mac OS X and is capable of generating self-installing binaries; py2app for creating Mac OS X applications; freeze, the original; and cx_freeze, which offers both Python 3.X and cross-platform support. You may have to fetch these tools separately from Python itself, but they are freely available.

These tools are also constantly evolving, so consult http://www.python.org or your favorite web search engine for more details and status. To give you an idea of the scope of these systems, py2exe can freeze standalone programs that use the tkinter, PMW, wxPython, and PyGTK GUI libraries; programs that use the pygame game programming toolkit; win32com client programs; and more.

Frozen binaries are not the same as the output of a true compiler—they run byte code through a virtual machine. Hence, apart from a possible startup improvement, frozen binaries run at the same speed as the original source files. Frozen binaries are also not generally small (they contain a PVM), but by current standards they are not unusually large either. Because Python is embedded in the frozen binary, though, it does not have to be installed on the receiving end to run your program. Moreover, because your code is embedded in the frozen binary, it is more effectively hidden from recipients.

This single file-packaging scheme is especially appealing to developers of commercial software. For instance, a Python-coded user interface program based on the tkinter toolkit can be frozen into an executable file and shipped as a self-contained program on a CD or on the Web. End users do not need to install (or even have to know about) Python to run the shipped program.

Future Possibilities?

Finally, note that the runtime execution model sketched here is really an artifact of the current implementation of Python, not of the language itself. For instance, it’s not impossible that a full, traditional compiler for translating Python source code to machine code may appear during the shelf life of this book (although the fact that one has not in over two decades makes this seem unlikely!).

New byte code formats and implementation variants may also be adopted in the future. For instance:

§ The ongoing Parrot project aims to provide a common byte code format, virtual machine, and optimization techniques for a variety of programming languages, including Python. Python’s own PVM runs Python code more efficiently than Parrot (as famously demonstrated by a pie challenge at a software conference—search the Web for details), but it’s unclear how Parrot will evolve in relation to Python specifically. See http://parrot.org or the Web at large for details.

§ The former Unladen Swallow project—an open source project developed by Google engineers—sought to make standard Python faster by a factor of at least 5, and fast enough to replace the C language in many contexts. This was an optimization branch of CPython (specifically Python 2.6), intended to be compatible yet faster by virtue of adding a JIT to standard Python. As I write this in 2012, this project seems to have drawn to a close (per its withdrawn Python PEP, it was “going the way of the Norwegian Blue”). Still, its lessons gained may be leveraged in other forms; search the Web for breaking developments.

Although future implementation schemes may alter the runtime structure of Python somewhat, it seems likely that the byte code compiler will still be the standard for some time to come. The portability and runtime flexibility of byte code are important features of many Python systems. Moreover, adding type constraint declarations to support static compilation would likely break much of the flexibility, conciseness, simplicity, and overall spirit of Python coding. Due to Python’s highly dynamic nature, any future implementation will likely retain many artifacts of the currentPVM.

Chapter Summary

This chapter introduced the execution model of Python—how Python runs your programs—and explored some common variations on that model: just-in-time compilers and the like. Although you don’t really need to come to grips with Python internals to write Python scripts, a passing acquaintance with this chapter’s topics will help you truly understand how your programs run once you start coding them. In the next chapter, you’ll start actually running some code of your own. First, though, here’s the usual chapter quiz.

Test Your Knowledge: Quiz

1. What is the Python interpreter?

2. What is source code?

3. What is byte code?

4. What is the PVM?

5. Name two or more variations on Python’s standard execution model.

6. How are CPython, Jython, and IronPython different?

7. What are Stackless and PyPy?

Test Your Knowledge: Answers

1. The Python interpreter is a program that runs the Python programs you write.

2. Source code is the statements you write for your program—it consists of text in text files that normally end with a .py extension.

3. Byte code is the lower-level form of your program after Python compiles it. Python automatically stores byte code in files with a .pyc extension.

4. The PVM is the Python Virtual Machine—the runtime engine of Python that interprets your compiled byte code.

5. Psyco, Shed Skin, and frozen binaries are all variations on the execution model. In addition, the alternative implementations of Python named in the next two answers modify the model in some fashion as well—by replacing byte code and VMs, or by adding tools and JITs.

6. CPython is the standard implementation of the language. Jython and IronPython implement Python programs for use in Java and .NET environments, respectively; they are alternative compilers for Python.

7. Stackless is an enhanced version of Python aimed at concurrency, and PyPy is a reimplementation of Python targeted at speed. PyPy is also the successor to Psyco, and incorporates the JIT concepts that Psyco pioneered.

All materials on the site are licensed Creative Commons Attribution-Sharealike 3.0 Unported CC BY-SA 3.0 & GNU Free Documentation License (GFDL)

If you are the copyright holder of any material contained on our site and intend to remove it, please contact our site administrator for approval.

© 2016-2025 All site design rights belong to S.Y.A.