Learning Python (2013)

Part II. Types and Operations

Chapter 6. The Dynamic Typing Interlude

In the prior chapter, we began exploring Python’s core object types in depth by studying Python numeric types and operations. We’ll resume our object type tour in the next chapter, but before we move on, it’s important that you get a handle on what may be the most fundamental idea in Python programming and is certainly the basis of much of both the conciseness and flexibility of the Python language—dynamic typing, and the polymorphism it implies.

As you’ll see here and throughout this book, in Python, we do not declare the specific types of the objects our scripts use. In fact, most programs should not even care about specific types; in exchange, they are naturally applicable in more contexts than we can sometimes even plan ahead for. Because dynamic typing is the root of this flexibility, and is also a potential stumbling block for newcomers, let’s take a brief side trip to explore the model here.

The Case of the Missing Declaration Statements

If you have a background in compiled or statically typed languages like C, C++, or Java, you might find yourself a bit perplexed at this point in the book. So far, we’ve been using variables without declaring their existence or their types, and it somehow works. When we type a = 3 in an interactive session or program file, for instance, how does Python know that a should stand for an integer? For that matter, how does Python know what a is at all?

Once you start asking such questions, you’ve crossed over into the domain of Python’s dynamic typing model. In Python, types are determined automatically at runtime, not in response to declarations in your code. This means that you never declare variables ahead of time (a concept that is perhaps simpler to grasp if you keep in mind that it all boils down to variables, objects, and the links between them).

Variables, Objects, and References

As you’ve seen in many of the examples used so far in this book, when you run an assignment statement such as a = 3 in Python, it works even if you’ve never told Python to use the name a as a variable, or that a should stand for an integer-type object. In the Python language, this all pans out in a very natural way, as follows:

Variable creation

A variable (i.e., name), like a, is created when your code first assigns it a value. Future assignments change the value of the already created name. Technically, Python detects some names before your code runs, but you can think of it as though initial assignments make variables.

Variable types

A variable never has any type information or constraints associated with it. The notion of type lives with objects, not names. Variables are generic in nature; they always simply refer to a particular object at a particular point in time.

Variable use

When a variable appears in an expression, it is immediately replaced with the object that it currently refers to, whatever that may be. Further, all variables must be explicitly assigned before they can be used; referencing unassigned variables results in errors.

In sum, variables are created when assigned, can reference any type of object, and must be assigned before they are referenced. This means that you never need to declare names used by your script, but you must initialize names before you can update them; counters, for example, must be initialized to zero before you can add to them.

This dynamic typing model is strikingly different from the typing model of traditional languages. When you are first starting out, the model is usually easier to understand if you keep clear the distinction between names and objects. For example, when we say this to assign a variable a value:

>>> a = 3 # Assign a name to an object

at least conceptually, Python will perform three distinct steps to carry out the request. These steps reflect the operation of all assignments in the Python language:

1. Create an object to represent the value 3.

2. Create the variable a, if it does not yet exist.

3. Link the variable a to the new object 3.

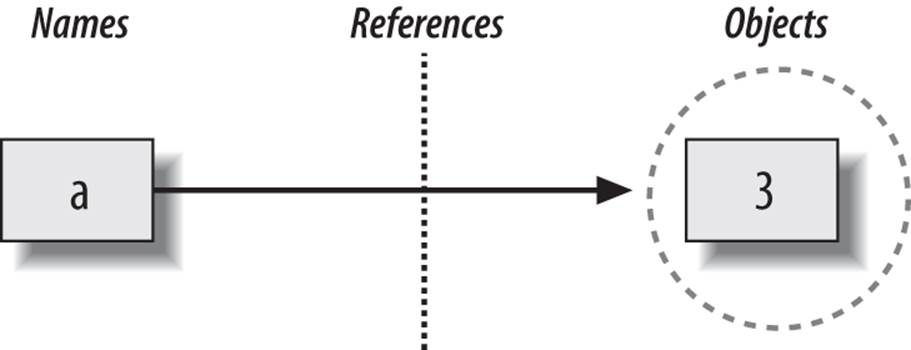

The net result will be a structure inside Python that resembles Figure 6-1. As sketched, variables and objects are stored in different parts of memory and are associated by links (the link is shown as a pointer in the figure). Variables always link to objects and never to other variables, but larger objects may link to other objects (for instance, a list object has links to the objects it contains).

Figure 6-1. Names and objects after running the assignment a = 3. Variable a becomes a reference to the object 3. Internally, the variable is really a pointer to the object’s memory space created by running the literal expression 3.

These links from variables to objects are called references in Python—that is, a reference is a kind of association, implemented as a pointer in memory.[15] Whenever the variables are later used (i.e., referenced), Python automatically follows the variable-to-object links. This is all simpler than the terminology may imply. In concrete terms:

§ Variables are entries in a system table, with spaces for links to objects.

§ Objects are pieces of allocated memory, with enough space to represent the values for which they stand.

§ References are automatically followed pointers from variables to objects.

At least conceptually, each time you generate a new value in your script by running an expression, Python creates a new object (i.e., a chunk of memory) to represent that value. As an optimization, Python internally caches and reuses certain kinds of unchangeable objects, such as small integers and strings (each 0 is not really a new piece of memory—more on this caching behavior later). But from a logical perspective, it works as though each expression’s result value is a distinct object and each object is a distinct piece of memory.

Technically speaking, objects have more structure than just enough space to represent their values. Each object also has two standard header fields: a type designator used to mark the type of the object, and a reference counter used to determine when it’s OK to reclaim the object. To understand how these two header fields factor into the model, we need to move on.

Types Live with Objects, Not Variables

To see how object types come into play, watch what happens if we assign a variable multiple times:

>>> a = 3 # It's an integer

>>> a = 'spam' # Now it's a string

>>> a = 1.23 # Now it's a floating point

This isn’t typical Python code, but it does work—a starts out as an integer, then becomes a string, and finally becomes a floating-point number. This example tends to look especially odd to ex-C programmers, as it appears as though the type of a changes from integer to string when we say a = 'spam'.

However, that’s not really what’s happening. In Python, things work more simply. Names have no types; as stated earlier, types live with objects, not names. In the preceding listing, we’ve simply changed a to reference different objects. Because variables have no type, we haven’t actually changed the type of the variable a; we’ve simply made the variable reference a different type of object. In fact, again, all we can ever say about a variable in Python is that it references a particular object at a particular point in time.

Objects, on the other hand, know what type they are—each object contains a header field that tags the object with its type. The integer object 3, for example, will contain the value 3, plus a designator that tells Python that the object is an integer (strictly speaking, a pointer to an object calledint, the name of the integer type). The type designator of the 'spam' string object points to the string type (called str) instead. Because objects know their types, variables don’t have to.

To recap, types are associated with objects in Python, not with variables. In typical code, a given variable usually will reference just one kind of object. Because this isn’t a requirement, though, you’ll find that Python code tends to be much more flexible than you may be accustomed to—if you use Python well, your code might work on many types automatically.

I mentioned that objects have two header fields, a type designator and a reference counter. To understand the latter of these, we need to move on and take a brief look at what happens at the end of an object’s life.

Objects Are Garbage-Collected

In the prior section’s listings, we assigned the variable a to different types of objects in each assignment. But when we reassign a variable, what happens to the value it was previously referencing? For example, after the following statements, what happens to the object 3?

>>> a = 3

>>> a = 'spam'

The answer is that in Python, whenever a name is assigned to a new object, the space held by the prior object is reclaimed if it is not referenced by any other name or object. This automatic reclamation of objects’ space is known as garbage collection, and makes life much simpler for programmers of languages like Python that support it.

To illustrate, consider the following example, which sets the name x to a different object on each assignment:

>>> x = 42

>>> x = 'shrubbery' # Reclaim 42 now (unless referenced elsewhere)

>>> x = 3.1415 # Reclaim 'shrubbery' now

>>> x = [1, 2, 3] # Reclaim 3.1415 now

First, notice that x is set to a different type of object each time. Again, though this is not really the case, the effect is as though the type of x is changing over time. Remember, in Python types live with objects, not names. Because names are just generic references to objects, this sort of code works naturally.

Second, notice that references to objects are discarded along the way. Each time x is assigned to a new object, Python reclaims the prior object’s space. For instance, when it is assigned the string 'shrubbery', the object 42 is immediately reclaimed (assuming it is not referenced anywhere else)—that is, the object’s space is automatically thrown back into the free space pool, to be reused for a future object.

Internally, Python accomplishes this feat by keeping a counter in every object that keeps track of the number of references currently pointing to that object. As soon as (and exactly when) this counter drops to zero, the object’s memory space is automatically reclaimed. In the preceding listing, we’re assuming that each time x is assigned to a new object, the prior object’s reference counter drops to zero, causing it to be reclaimed.

The most immediately tangible benefit of garbage collection is that it means you can use objects liberally without ever needing to allocate or free up space in your script. Python will clean up unused space for you as your program runs. In practice, this eliminates a substantial amount of bookkeeping code required in lower-level languages such as C and C++.

MORE ON PYTHON GARBAGE COLLECTION

Technically speaking, Python’s garbage collection is based mainly upon reference counters, as described here; however, it also has a component that detects and reclaims objects with cyclic references in time. This component can be disabled if you’re sure that your code doesn’t create cycles, but it is enabled by default.

Circular references are a classic issue in reference count garbage collectors. Because references are implemented as pointers, it’s possible for an object to reference itself, or reference another object that does. For example, exercise 3 at the end of Part I and its solution in Appendix D show how to create a cycle easily by embedding a reference to a list within itself (e.g., L.append(L)). The same phenomenon can occur for assignments to attributes of objects created from user-defined classes. Though relatively rare, because the reference counts for such objects never drop to zero, they must be treated specially.

For more details on Python’s cycle detector, see the documentation for the gc module in Python’s library manual. The best news here is that garbage-collection-based memory management is implemented for you in Python, by people highly skilled at the task.

Also note that this chapter’s description of Python’s garbage collector applies to the standard Python (a.k.a. CPython) only; Chapter 2’s alternative implementations such as Jython, IronPython, and PyPy may use different schemes, though the net effect in all is similar—unused space is reclaimed for you automatically, if not always as immediately.

[15] Readers with a background in C may find Python references similar to C pointers (memory addresses). In fact, references are implemented as pointers, and they often serve the same roles, especially with objects that can be changed in place (more on this later). However, because references are always automatically dereferenced when used, you can never actually do anything useful with a reference itself; this is a feature that eliminates a vast category of C bugs. But you can think of Python references as C “void*” pointers, which are automatically followed whenever used.

Shared References

So far, we’ve seen what happens as a single variable is assigned references to objects. Now let’s introduce another variable into our interaction and watch what happens to its names and objects:

>>> a = 3

>>> b = a

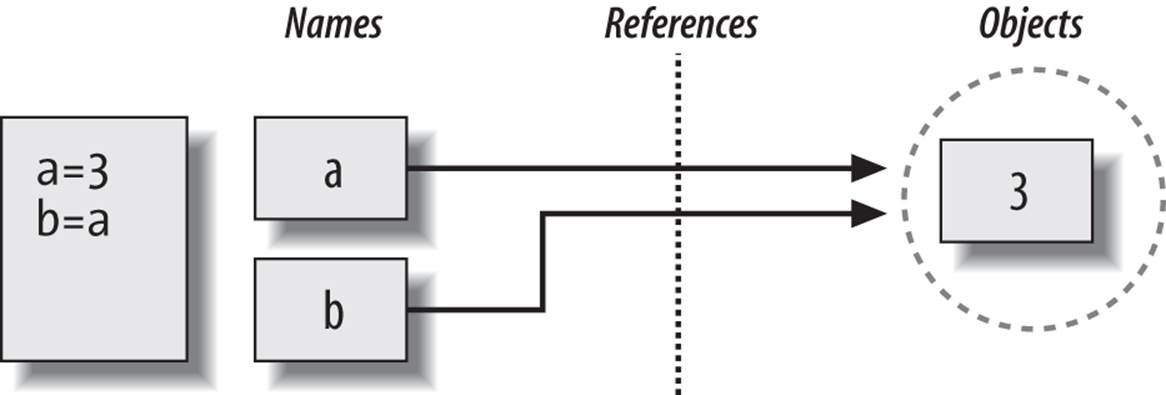

Typing these two statements generates the scene captured in Figure 6-2. The second command causes Python to create the variable b; the variable a is being used and not assigned here, so it is replaced with the object it references (3), and b is made to reference that object. The net effect is that the variables a and b wind up referencing the same object (that is, pointing to the same chunk of memory).

Figure 6-2. Names and objects after next running the assignment b = a. Variable b becomes a reference to the object 3. Internally, the variable is really a pointer to the object’s memory space created by running the literal expression 3.

This scenario in Python—with multiple names referencing the same object—is usually called a shared reference (and sometimes just a shared object). Note that the names a and b are not linked to each other directly when this happens; in fact, there is no way to ever link a variable to another variable in Python. Rather, both variables point to the same object via their references.

Next, suppose we extend the session with one more statement:

>>> a = 3

>>> b = a

>>> a = 'spam'

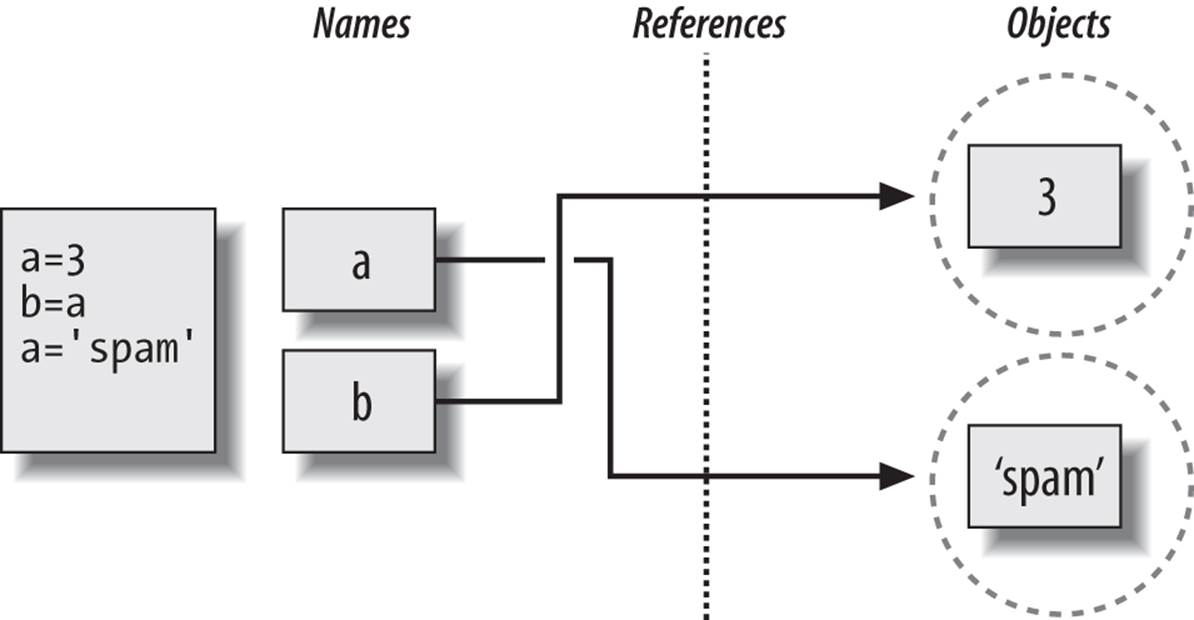

As with all Python assignments, this statement simply makes a new object to represent the string value 'spam' and sets a to reference this new object. It does not, however, change the value of b; b still references the original object, the integer 3. The resulting reference structure is shown inFigure 6-3.

Figure 6-3. Names and objects after finally running the assignment a = ‘spam’. Variable a references the new object (i.e., piece of memory) created by running the literal expression ‘spam’, but variable b still refers to the original object 3. Because this assignment is not an in-place change to the object 3, it changes only variable a, not b.

The same sort of thing would happen if we changed b to 'spam' instead—the assignment would change only b, not a. This behavior also occurs if there are no type differences at all. For example, consider these three statements:

>>> a = 3

>>> b = a

>>> a = a + 2

In this sequence, the same events transpire. Python makes the variable a reference the object 3 and makes b reference the same object as a, as in Figure 6-2; as before, the last assignment then sets a to a completely different object (in this case, the integer 5, which is the result of the +expression). It does not change b as a side effect. In fact, there is no way to ever overwrite the value of the object 3—as introduced in Chapter 4, integers are immutable and thus can never be changed in place.

One way to think of this is that, unlike in some languages, in Python variables are always pointers to objects, not labels of changeable memory areas: setting a variable to a new value does not alter the original object, but rather causes the variable to reference an entirely different object. The net effect is that assignment to a variable itself can impact only the single variable being assigned. When mutable objects and in-place changes enter the equation, though, the picture changes somewhat; to see how, let’s move on.

Shared References and In-Place Changes

As you’ll see later in this part’s chapters, there are objects and operations that perform in-place object changes—Python’s mutable types, including lists, dictionaries, and sets. For instance, an assignment to an offset in a list actually changes the list object itself in place, rather than generating a brand-new list object.

Though you must take it somewhat on faith at this point in the book, this distinction can matter much in your programs. For objects that support such in-place changes, you need to be more aware of shared references, since a change from one name may impact others. Otherwise, your objects may seem to change for no apparent reason. Given that all assignments are based on references (including function argument passing), it’s a pervasive potential.

To illustrate, let’s take another look at the list objects introduced in Chapter 4. Recall that lists, which do support in-place assignments to positions, are simply collections of other objects, coded in square brackets:

>>> L1 = [2, 3, 4]

>>> L2 = L1

L1 here is a list containing the objects 2, 3, and 4. Items inside a list are accessed by their positions, so L1[0] refers to object 2, the first item in the list L1. Of course, lists are also objects in their own right, just like integers and strings. After running the two prior assignments, L1 and L2reference the same shared object, just like a and b in the prior example (see Figure 6-2). Now say that, as before, we extend this interaction to say the following:

>>> L1 = 24

This assignment simply sets L1 to a different object; L2 still references the original list. If we change this statement’s syntax slightly, however, it has a radically different effect:

>>> L1 = [2, 3, 4] # A mutable object

>>> L2 = L1 # Make a reference to the same object

>>> L1[0] = 24 # An in-place change

>>> L1 # L1 is different

[24, 3, 4]

>>> L2 # But so is L2!

[24, 3, 4]

Really, we haven’t changed L1 itself here; we’ve changed a component of the object that L1 references. This sort of change overwrites part of the list object’s value in place. Because the list object is shared by (referenced from) other variables, though, an in-place change like this doesn’t affect only L1—that is, you must be aware that when you make such changes, they can impact other parts of your program. In this example, the effect shows up in L2 as well because it references the same object as L1. Again, we haven’t actually changed L2, either, but its value will appear different because it refers to an object that has been overwritten in place.

This behavior only occurs for mutable objects that support in-place changes, and is usually what you want, but you should be aware of how it works, so that it’s expected. It’s also just the default: if you don’t want such behavior, you can request that Python copy objects instead of making references. There are a variety of ways to copy a list, including using the built-in list function and the standard library copy module. Perhaps the most common way is to slice from start to finish (see Chapter 4 and Chapter 7 for more on slicing):

>>> L1 = [2, 3, 4]

>>> L2 = L1[:] # Make a copy of L1 (or list(L1), copy.copy(L1), etc.)

>>> L1[0] = 24

>>> L1

[24, 3, 4]

>>> L2 # L2 is not changed

[2, 3, 4]

Here, the change made through L1 is not reflected in L2 because L2 references a copy of the object L1 references, not the original; that is, the two variables point to different pieces of memory.

Note that this slicing technique won’t work on the other major mutable core types, dictionaries and sets, because they are not sequences—to copy a dictionary or set, instead use their X.copy() method call (lists have one as of Python 3.3 as well), or pass the original object to their type names, dict and set. Also, note that the standard library copy module has a call for copying any object type generically, as well as a call for copying nested object structures—a dictionary with nested lists, for example:

import copy

X = copy.copy(Y) # Make top-level "shallow" copy of any object Y

X = copy.deepcopy(Y) # Make deep copy of any object Y: copy all nested parts

We’ll explore lists and dictionaries in more depth, and revisit the concept of shared references and copies, in Chapter 8 and Chapter 9. For now, keep in mind that objects that can be changed in place (that is, mutable objects) are always open to these kinds of effects in any code they pass through. In Python, this includes lists, dictionaries, sets, and some objects defined with class statements. If this is not the desired behavior, you can simply copy your objects as needed.

Shared References and Equality

In the interest of full disclosure, I should point out that the garbage-collection behavior described earlier in this chapter may be more conceptual than literal for certain types. Consider these statements:

>>> x = 42

>>> x = 'shrubbery' # Reclaim 42 now?

Because Python caches and reuses small integers and small strings, as mentioned earlier, the object 42 here is probably not literally reclaimed; instead, it will likely remain in a system table to be reused the next time you generate a 42 in your code. Most kinds of objects, though, are reclaimed immediately when they are no longer referenced; for those that are not, the caching mechanism is irrelevant to your code.

For instance, because of Python’s reference model, there are two different ways to check for equality in a Python program. Let’s create a shared reference to demonstrate:

>>> L = [1, 2, 3]

>>> M = L # M and L reference the same object

>>> L == M # Same values

True

>>> L is M # Same objects

True

The first technique here, the == operator, tests whether the two referenced objects have the same values; this is the method almost always used for equality checks in Python. The second method, the is operator, instead tests for object identity—it returns True only if both names point to the exact same object, so it is a much stronger form of equality testing and is rarely applied in most programs.

Really, is simply compares the pointers that implement references, and it serves as a way to detect shared references in your code if needed. It returns False if the names point to equivalent but different objects, as is the case when we run two different literal expressions:

>>> L = [1, 2, 3]

>>> M = [1, 2, 3] # M and L reference different objects

>>> L == M # Same values

True

>>> L is M # Different objects

False

Now, watch what happens when we perform the same operations on small numbers:

>>> X = 42

>>> Y = 42 # Should be two different objects

>>> X == Y

True

>>> X is Y # Same object anyhow: caching at work!

True

In this interaction, X and Y should be == (same value), but not is (same object) because we ran two different literal expressions (42). Because small integers and strings are cached and reused, though, is tells us they reference the same single object.

In fact, if you really want to look under the hood, you can always ask Python how many references there are to an object: the getrefcount function in the standard sys module returns the object’s reference count. When I ask about the integer object 1 in the IDLE GUI, for instance, it reports 647 reuses of this same object (most of which are in IDLE’s system code, not mine, though this returns 173 outside IDLE so Python must be hoarding 1s as well):

>>> import sys

>>> sys.getrefcount(1) # 647 pointers to this shared piece of memory

647

This object caching and reuse is irrelevant to your code (unless you run the is check!). Because you cannot change immutable numbers or strings in place, it doesn’t matter how many references there are to the same object—every reference will always see the same, unchanging value. Still, this behavior reflects one of the many ways Python optimizes its model for execution speed.

Dynamic Typing Is Everywhere

Of course, you don’t really need to draw name/object diagrams with circles and arrows to use Python. When you’re starting out, though, it sometimes helps you understand unusual cases if you can trace their reference structures as we’ve done here. If a mutable object changes out from under you when passed around your program, for example, chances are you are witnessing some of this chapter’s subject matter firsthand.

Moreover, even if dynamic typing seems a little abstract at this point, you probably will care about it eventually. Because everything seems to work by assignment and references in Python, a basic understanding of this model is useful in many different contexts. As you’ll see, it works the same in assignment statements, function arguments, for loop variables, module imports, class attributes, and more. The good news is that there is just one assignment model in Python; once you get a handle on dynamic typing, you’ll find that it works the same everywhere in the language.

At the most practical level, dynamic typing means there is less code for you to write. Just as importantly, though, dynamic typing is also the root of Python’s polymorphism, a concept we introduced in Chapter 4 and will revisit again later in this book. Because we do not constrain types in Python code, it is both concise and highly flexible. As you’ll see, when used well, dynamic typing—and the polymorphism it implies—produces code that automatically adapts to new requirements as your systems evolve.

“WEAK” REFERENCES

You may occasionally see the term “weak reference” in the Python world. This is a somewhat advanced tool, but is related to the reference model we’ve explored here, and like the is operator, can’t really be understood without it.

In short, a weak reference, implemented by the weakref standard library module, is a reference to an object that does not by itself prevent the referenced object from being garbage-collected. If the last remaining references to an object are weak references, the object is reclaimed and the weak references to it are automatically deleted (or otherwise notified).

This can be useful in dictionary-based caches of large objects, for example; otherwise, the cache’s reference alone would keep the object in memory indefinitely. Still, this is really just a special-case extension to the reference model. For more details, see Python’s library manual.

Chapter Summary

This chapter took a deeper look at Python’s dynamic typing model—that is, the way that Python keeps track of object types for us automatically, rather than requiring us to code declaration statements in our scripts. Along the way, we learned how variables and objects are associated by references in Python; we also explored the idea of garbage collection, learned how shared references to objects can affect multiple variables, and saw how references impact the notion of equality in Python.

Because there is just one assignment model in Python, and because assignment pops up everywhere in the language, it’s important that you have a handle on the model before moving on. The following quiz should help you review some of this chapter’s ideas. After that, we’ll resume our core object tour in the next chapter, with strings.

Test Your Knowledge: Quiz

1. Consider the following three statements. Do they change the value printed for A?

2. A = "spam"

3. B = A

4. B = "shrubbery"

5. Consider these three statements. Do they change the printed value of A?

6. A = ["spam"]

7. B = A

8. B[0] = "shrubbery"

9. How about these—is A changed now?

10.A = ["spam"]

11.B = A[:]

12.B[0] = "shrubbery"

Test Your Knowledge: Answers

1. No: A still prints as "spam". When B is assigned to the string "shrubbery", all that happens is that the variable B is reset to point to the new string object. A and B initially share (i.e., reference/point to) the same single string object "spam", but two names are never linked together in Python. Thus, setting B to a different object has no effect on A. The same would be true if the last statement here were B = B + 'shrubbery', by the way—the concatenation would make a new object for its result, which would then be assigned to B only. We can never overwrite a string (or number, or tuple) in place, because strings are immutable.

2. Yes: A now prints as ["shrubbery"]. Technically, we haven’t really changed either A or B; instead, we’ve changed part of the object they both reference (point to) by overwriting that object in place through the variable B. Because A references the same object as B, the update is reflected in A as well.

3. No: A still prints as ["spam"]. The in-place assignment through B has no effect this time because the slice expression made a copy of the list object before it was assigned to B. After the second assignment statement, there are two different list objects that have the same value (in Python, we say they are ==, but not is). The third statement changes the value of the list object pointed to by B, but not that pointed to by A.

All materials on the site are licensed Creative Commons Attribution-Sharealike 3.0 Unported CC BY-SA 3.0 & GNU Free Documentation License (GFDL)

If you are the copyright holder of any material contained on our site and intend to remove it, please contact our site administrator for approval.

© 2016-2025 All site design rights belong to S.Y.A.