Digital Archaeology (2014)

17. Case Management and Report Writing

The ancient Egyptians took their case documentation very seriously. The Abbot Papyrus is one of the earliest examples of an investigation being documented by the officials assigned to the case. Ramses IX ordered an investigation into tomb robberies that plagued the kingdom. The method by which the ancient Egyptian investigators approached their subject is made very clear. And obviously a permanent document was created to record the findings, or we wouldn’t know about it today. There were no computers involved, but the precedent remains intact.

As the title infers, there are two different but related subjects covered in this chapter. Properly managing a case minimizes the duplication of efforts and maximizes the return on time and money invested. The concept of documentation is one that has emerged many times throughout the course of this book. Here is where the various forms of documentation that will be prepared in the course of an investigation will be examined. Failure to efficiently manage a case and failure to prepare adequate documentation are both likely to have the same result—failure.

Managing a Case

The least desirable component of any investigation to many professionals is the administrative aspects of preparing, executing, and presenting a specific case. Still, without this aspect, an investigation will quickly become disorganized and inefficient. Additionally, many investigations that wind their way into the courts take many years to go through the process. A gentleman I interviewed in the process of completing my graduate degree told me of a case that was just going to an appeal that he started 12 years earlier. To be able to accurately report the results of a digital investigation that long after the actual events occurred—whether it is criminal, civil, or internal in nature—requires attention to detail.

In Chapter 1, “The Anatomy of a Digital Investigation,” we discussed the investigative model. Several papers have been written on different frameworks that can be applied to the investigative process. A framework is simply a method by which a case can be broken down into segments and each segment managed as a separate entity. Each of these approaches takes the investigative model (or some variation on the theme) into consideration and breaks a case down into phases in which each component of the model is addressed. Most of the defined frameworks are similar in nature and vary mostly in philosophical approach.

The Department of Justice model is a four-phase process that is evidence driven. The phases consist of collection, examination, analysis, and reporting. Preparation is assumed, and presentation is integrated into the reporting process (U.S. DOJ 2004).

Kruse and Heiser (2001) simplify an investigation into three steps, also evidence driven. Those phases are acquiring the evidence, authenticating the evidence, and analyzing the data. The assumption is that preparation and reporting are not in integral part of the investigative process.

The one that I personally find appealing is an objective-based framework proposed by Beebe and Clark (2005). It suggests that each investigation be divided into three stages (Figure 17.1), with each stage subsequently divided into phases. Stages are sequential and dependent on the completion of its predecessor before it can be initiated. An investigation cannot begin until preparation is complete, and it is impossible to present findings until the investigation is finished. The one overlapping principle that ties all the stages together is the correct interpretation and application of law.

Figure 17.1 The objective-based framework consists of three stages.

Interestingly enough, each stage can be further broken down into these same three stages. There is a preparation, investigation, and presentation stage for each preparation, investigation, and presentation you do.

The Preparation Stage

The preparation stage is done outside of the general scope of any specific investigation. This is the part where the organization or the investigative team sets the groundwork to be prepared for the any of the disasters that will inevitably occur. Organizations preparing for internal investigations have different priorities—and therefore will prepare somewhat differently—than a criminal investigation team. Still, there is a significant amount of overlap.

Whether setting up an internal forensics division for a large corporation or a new team for a law enforcement agency, the preparation stage is a lot of work in itself. Starting a new endeavor of this nature would be the subject of an entire book, but it will be covered in some detail in Chapter 21, “The Business of Digital Forensics.” Getting the necessary approvals and lining up the appropriate personnel is the preparation stage for the preparation stage.

The types of threats that an organization faces or that a team is equipped to handle need to be identified, quantified, and documented. Just like a bank responding to regulatory requirements, a group preparing for digital investigation capacity needs to develop an information retention policy and plan. What information must be collected, how will it be securely stored, and when the time comes to get rid of it, how can it be securely destroyed?

Develop your technical capabilities, and know precisely what they are and, more important, what the limitations are. During this part of the first stage, it will be important to engage everyone involved with the process to analyze what requirements are needed and to make sure that the resources are available to fulfill those requirements. An investigation team with nobody trained in cell phone capture and analysis, and that does not have the apparatus and software for performing such tasks, is in no position to accept responsibility for an investigation where cell phones are paramount to the investigation.

Create, distribute, and enforce strict policies and plans for each stage of an investigation. Don’t reinvent the wheel with each new project. There should be specific incident response plans with flexibility to deal with live response as well as static capture. A strict file-naming convention for evidence files should be enforced from the beginning. Many software products create default file names that will make no sense to a user six months down the road. Every computer file should clearly relate to the case for which it was generated. Evidence handling procedures, chain of custody reporting, documentation standards, and reporting protocol must be predefined and understood by everyone on the team.

Everyone on the team should have specific roles and assignments. It goes without saying that they need to be properly trained to perform their jobs, but ongoing refresher training must be part of the mix.

Acquiring facilities is a critical part of the preparation phase. Imagine the confusion that would result from a first-response team arriving at the office with a half dozen computers and several pieces of media that need immediate analysis and the workstations are all being used by the administrative staff to process payroll. How much fun will it be to capture a 750GB hard disk and find out that your 1TB host storage is still full from the last job? Evidence handling and storage is a critical part of facilities management. It is critical that your team be able to demonstrate that all evidentiary materials were safe and secure and free from tampering the entire time they were in your possession.

Know in advance who you can consult regarding legal issues. Develop working relationships with several vendors who specialize in your type of products and services. You never know when you might need a couple of 2TB drives drop-shipped to a field site or need to subcontract a service you can’t provide. Have emergency contact information available for all personnel and know who controls your budget and what your budget limitations are. You cannot begin your first investigation until all of the above is in place, but you have at least completed the investigation phase of preparation.

Equally important is that all of the above be clearly documented and available in a location easily accessible to key personnel. Ensure that all necessary information for submitting business change requests and project control forms has been collected. The policies that are generated during this phase, as well as contact information, should be posted where all the relevant people can find it. If just the division manager knows all this information, who will be able to take over when she steps out in front of a bus?

The Investigation Stage

When an actual case lands in the department’s hands, it will be time to start the investigation stage, because all of the preparatory steps have already been taken. A case is initiated through some form of alert. Either the manager of a department suspects an intrusion or some form of malfeasance, or a warrant has been issued for the search and seizure of digital devices.

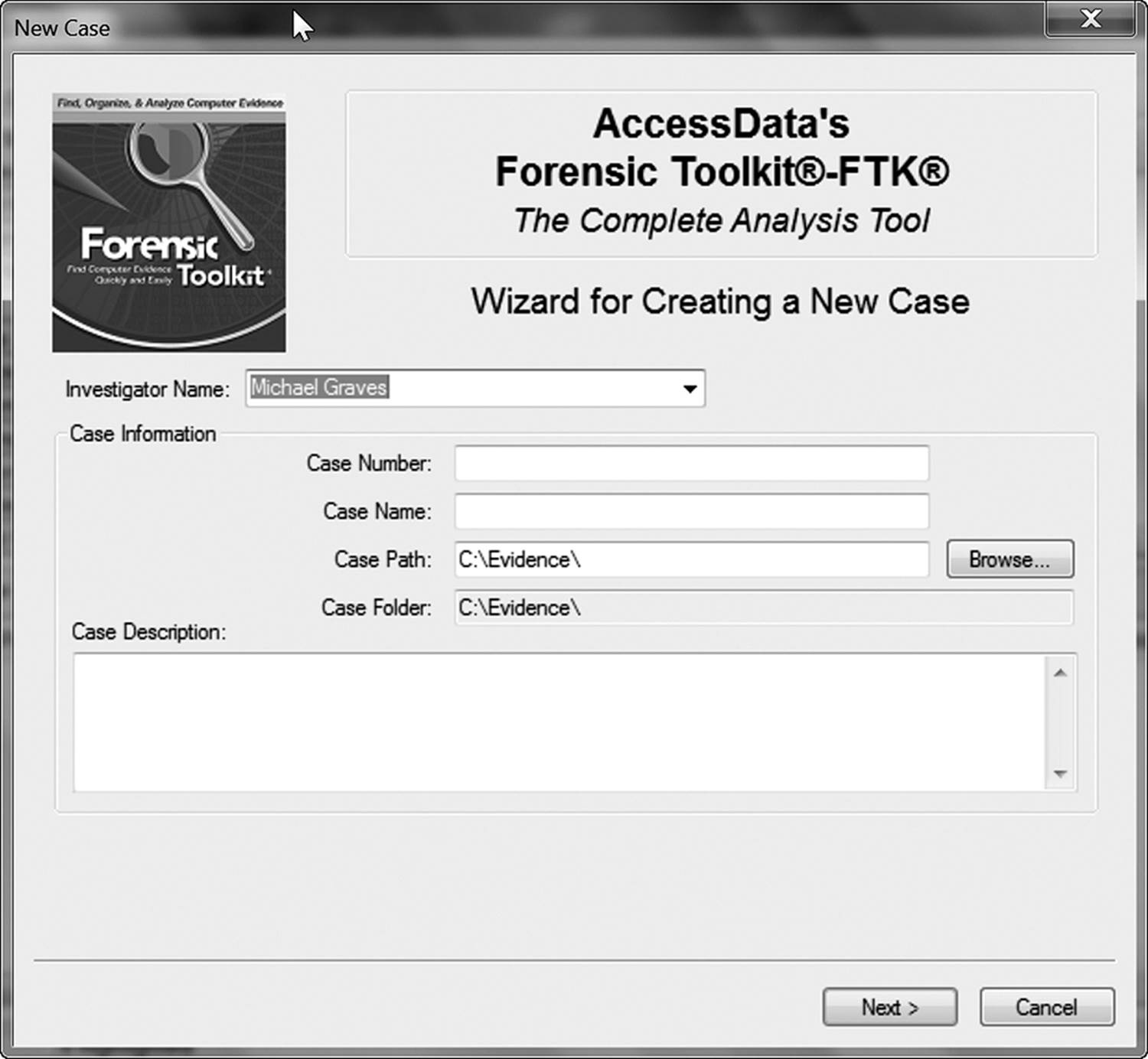

Preparing for the investigation stage is generally straightforward. Most of the commercial forensic suites automate much of the process of documentation, but there is still some preliminary thinking involved. This is where the file-name conventions mentioned earlier come into play. Access Data’s Forensic Tool Kit (Figure 17.2) is a good example of a suite with automated documentation.

Figure 17.2 The first step in any investigation is beginning the case documentation. Most forensic suites help by automating this process.

Triage

Depending on the type of situation and the severity, there might be several options for proceeding. Working with everybody involved in the investigation, it will be necessary to establish priorities. This is similar to the triage that doctors do on the battlefield. Dress the worst wounds first. In a situation involving large networks or very sensitive information, it is very likely that protecting the data carries a higher priority than collecting evidence. Cutting an active hacker off from a database of credit card information may be deemed more important that backtracing the connection to identify the culprit. A list of priorities might evolve from asking these questions:

• Is there potential risk of injury or death?

• Does either activity or inactivity lead to loss or serious damage to infrastructure?

• Is the private information of customers or employees at risk?

• Is there a significant risk of financial loss?

• Is identifying the culprit a high enough priority to introduce any of the above risks?

First Response

Once dispatched to the scene of the incident, there are certain rules to follow. Chapter 6, “First Response and the Digital Investigator,” covers most of this in more detail. However, from a case-management point of view, it is essential to create a solid foundation that the remainder of the case will rest upon. It is always best to treat any incident as though it were a crime scene, even if it is a simple internal investigation.

The first response team will need to make an assessment of how to proceed in the collection of evidence. A response strategy must be decided upon before the first piece of evidence is touched. Will live response be needed? Generally speaking, unless there is a clear indication that live response will do more harm than good, it is best to proceed with the assumption that it will be. Regardless of whether live response is conducted or not, record the active state of each device examined as it is initially found. Is it on or off? If it is on, is it in screensaver mode? Are other forensic investigators involved? If so, there may be a degree of cooperation involved regarding whether fingerprints should be collected prior to live response or the live responder should go first, wearing gloves to prevent contamination.

Make an inventory of every item that will be examined, whether it is being taken off-site for examination or not. Collect the make, model, and serial numbers of each device. Where applicable, record the stated capacity of storage devices. Make note of the battery charge on any portable device that needs to be transported, especially if it needs to remain in the on position until it is looked at. For any items being transported, begin the chain of custody immediately and have someone with authority sign off on the time and date that the item was released and to whom it was released. That person must also sign or initial the chain of custody report. Every time the item changes hands, record the event, including exact times and dates, identifying who handed it off and who received it.

Crime Scene Management

While not every investigation strictly involves criminal activity, it is best if the investigation team approaches each incident as though it did. That way, in the event that criminal activity is uncovered, the evidence won’t already be inadmissible because of bungling on your team’s part. Carrier (2003) identifies the following phases to crime scene management:

• Crime Scene Preservation: Secure the scene, and detain any witnesses. If physical violence has occurred, tend to any injured people. If the suspect is present, detain that person.

• Crime Scene Survey: Don’t do anything that might spoil evidence. If anything must be moved, carefully avoid any contact that could potentially damage existing fingerprints and be sure that you don’t add your own. Take note of all people who are on the scene at the time of arrival. Identify anything that is clearly evidentiary in nature, and secure it.

• Crime Scene Documentation: Photograph and, if possible, make a video survey of the scene. Any materials that are collected as evidence must be carefully documented as described in the previous section of this chapter. It is essential to work with any other forensic teams during this phase to assure that the preservation of your evidence doesn’t have a negative impact on the ability of others to do their jobs. Fingerprints from the keyboard may need to be collected before you attempt live response activities.

• Crime Scene Search: Look for additional evidence that may be concealed. In most “real” crime scenes, the forensic team breaks down the area into grids and goes over every square inch with the proverbial fine-tooth comb. In an initial response involving civil claims or internal investigations, it is likely that this part of the search will not occur. Still, it is important for your team to find things such as slips of paper with possible passwords, thumb drives tucked into drawers, notes about Web sites, or file names that the suspect may have jotted down by hand. Nearly everybody writes things down, even when using a computer.

• Crime Scene Reconstruction: Once again, this phase may not be necessary in anything but an actual crime scene. However, it is commonplace for forensic teams to try to analyze the location and position of various items at the scene to determine how things might have occurred. From a computer operator’s point of view, this might include details such as what side of the computer the mouse is located (is the suspect right-handed or left-handed?), whether the computer display was configured for a sight-impaired person, and so forth.

Lab Preparation

While the response team is working their magic, there is a lot of work that can be done at the lab as well. There must be a single repository for all files generated during the investigation. While it is preferable that new media be used for storing files, existing disks and platters may be used as long as they are subjected to a DOD-approved wipe process to eliminate any possibility of cross-talk from a previous investigation. If this is the path taken, document the process of preparing media for case files.

Figure out how much storage will be needed for all the forensic images that will be prepared—and then allow for about twice that capacity. Forensic investigations are probably more susceptible to scope creep than any other project. Identify the personnel who will be assigned to the project, and make the appropriate assignments. Most importantly, make sure that all legal authority required to initiate the investigation is in place. If it is a criminal investigation, have the warrant in hand.

For an internal investigation, you need to make sure not only that you have written authorization but that the authorization is issued by somebody who actually has that authority. I was once involved in a situation where a manager authorized the search of several corporate computers in order to assess the damage caused by a disgruntled employee. Only as fate would have it, that manager had not cleared his decision with executive management. The damage control that followed that event was extensive.

Evidence Handling

The method by which evidentiary materials are transported from one site to another is a critical aspect of the investigation stage. Any external or environmental condition that damages the data hurts the investigation. Any suggestion that such conditions may have existed hurts the credibility of the results. Some suggestions for transporting digital evidence include

• Use antistatic bags for anything that holds magnetically stored information.

• Use Faraday bags for transporting wireless devices.

• If a battery-operated device is still in the on position, try to keep it powered up.

• Don’t let magnetic media or circuit boards come in contact with any surfaces that may be statically charged.

• Keep magnetic media away from loudspeakers, heated car seats, radios, or any other device that may emanate electromagnetic radiation.

• If there is reason to transport monitors, make sure the screen is protected from possible impact. Find out if other forensic teams are going to need fingerprints.

• Don’t let evidentiary materials be exposed to temperature extremes.

• If unplugging devices such as hard disks from enclosures, take extreme care not to damage connectors.

• Don’t let any evidence get wet, dirty, or dropped.

If any of the aforementioned events do occur, document when, where, and how it happened. Report anything that may have caused such an incident to occur. Try to assess any possible impact it may have had on the authenticity or reliability of any evidence that might be obtained from the affected device.

For any materials transported off-site for examination, document where and how these items are to be stored while in the possession of the investigation team. Any time an item is checked in or out of the evidence locker, the transaction must be recorded in the chain of custody log. Additionally, anytime an item changes hands, that transfer must be recorded. Any break in the chain that the opposition can find will cast doubt on any evidence returned by that device. Storage must be secure and monitored. Larger organizations most likely will have a locked facility with controlled access. This type of control is mandatory for the storage of evidence used in a criminal investigation.

In addition to security, there are several other aspects of the storage environment that must be considered. Temperature and humidity should be carefully controlled. Too much or too little of either one can damage circuits or corrupt data under the right conditions. The environment should be as static free as possible. There are commercially available antistatic floor mats and counter mats that help out in this regard. A permanent facility can be designed to include Faraday shielding in the walls to prevent outside connections to be made with wireless devices stored within. There needs to be sufficient space in the storage facility to allow the evidence from multiple cases to coexist without any possibility that they will become comingled.

Evidence Examination

Once the examination of the evidence actually begins, the documentation and reporting become an integral part of the investigation. The examination starts with a hypothesis, and the goal of the investigation is to prove or disprove that hypothesis. Generally speaking, the hypothesis is presented for you. If the assignment is to look for pirated music on a server, the hypothesis is that somebody has intentionally acquired the illegal material and deliberately stored it.

Each examination must be conducted using the correct tool for the job. Just like you are not supposed to use a bigger wrench as a hammer, you don’t use Windows Explorer to make forensic copies. As pointed out in previous chapters, record what tool was used for each process and document each step taken, along with the time and date it occurred. Work only from copies of the data. Never do anything that can alter, damage, or destroy the original. Every time a new copy is made, hash the copy and compare the values. Make sure you’re working with an identical copy. Always remember that you are not just looking for incriminating evidence. As an investigator, you do not take sides. Look carefully for any exculpatory evidence as well.

While analyzing the results of the examination, follow all the same rules. Keep accurate records, because these reports will be the presentation that results from this stage of the investigation.

Throughout the course of the investigation, the team should have regular meetings. Each member of the team should be aware of what the other members are doing. Information found by one person might be the clue that helps another find the way. Brainstorming sessions and general rap sessions where people compare results do a lot for keeping a case moving along. These meetings also help out later on in the presentation stage when one or more members are called upon to testify.

The Presentation Stage

The final act of any investigation is presenting the results. A final report accomplishes two things. First of all, it clearly explains what was found during the examination of the evidence. Remember that it isn’t the job of the investigation team to interpret results—only to present them. A photograph may appear to be pornographic in nature to you and your team, but a jury may not agree. Therefore your report does not list 107 pornographic images. It lists 107 graphic images of people doing whatever it is they are doing in the photograph. A detailed description of a murder might read like evidence of a crime to most people, but in the final tally, it may simply be a chapter out of the suspect’s next novel.

The second aspect of the report is to prove that the evidence is what you say it is and that the methods you used to obtain that evidence were valid procedures and performed in an acceptable manner. Using the pirated music hypothesis described above, the investigation should be able to prove these key points:

• Music downloads do exist on the system.

• No exculpatory evidence indicates that the songs were obtained legally.

• The evidence points to an individual or individuals who were responsible for copying the files to the system.

• No other evidence was found linking any other individuals to the files.

If the additional allegation was made that file-sharing was taking place, there would need to be evidence collected that pointed to that as well. Network packet capture, logs showing network connections with suspect devices, and so forth could point to data transfer between two points.

There always exists the possibility that one or more investigators will be called upon to testify at a hearing or a trial. If that happens, whoever will be performing this onerous duty must be completely familiar with the case in its entirety. Remember those meetings I discussed in the previous section. This is one very good reason why they are important.

Writing Reports

Writing reports is probably the least favorite part of any investigator’s job. The resistance becomes exacerbated when multiple investigators are involved. The final report can be a voluminous manuscript and require the cooperative effort of several people.

Contents of a Reporting Package

In actuality, there are several documents that comprise the final report:

• The original request for an investigation to be conducted

• Copies of any authorizations issued (there may be several)

• An inventory of all devices touched by the investigative team

• A chain of custody report for any device seized by the team

• All case logs generated by members of the team

• All case notes maintained by members of the team

• Photographs and/or videos taken by the first-response team

• The final report of the investigation team

The final report is likely to be the most voluminous. It will contain summaries of much of the information listed in the preceding list. Additionally, it will contain a detailed description of the investigation as well as any conclusions derived from the process. Information contained in the final report will include, at a minimum, the following pieces of information:

• An identification of the reporting agency or individual

• The name of the person directly submitting the request

• The date of submission

• Any case numbers assigned by both the reporting agency and the internal team

• The date that the case was accepted for review

• The names of investigators assigned to the case

• A detailed report submitted by the first-response team (if applicable)

• A list of all items examined described by manufacturer, make, model, serial number, and capacity (if applicable)

• Descriptions of each step taken in the course of the investigation, including

• Name of investigator conducting the procedure

• Tool used for each procedure

• Times and dates marking the beginning and end of each procedure

• Specific parameters for any given procedure (such as search strings employed, header and footer information used in data-carving procedures, etc.)

• The results of each procedure (if no results obtained, indicate this in the report)

• Conclusions arrived at by the team

Textual material within the report must be factual with no expression of opinion about what the result may mean in terms of innocence or guilt. That is the job of the jury to decide such matters.

Structure of a Forensic Report

There are as many different variations on the “template” for a final forensic report as there are agencies and companies doing the reporting. Various places on the Web offer templates for download, some which come at a significant cost. Essentially, every organization will eventually have to prepare their own template based on work flow and the categories of investigation in which they specialize. There are some uniform components that will be a part of any report. Without them, the report would be incomplete.

The Case Summary

In the case summary, the basic information about the situation is briefly described. What happened to lead to an investigation being launched? If this was a news story, the basic questions would be Who, What, When, and Where. The How and Why will hopefully become a part of your summary.

Who reported the incident? Who all is involved? Provide a list of every individual that is involved in the case, starting with who filed the report, all the way to the names of the people conducting the investigation.

Record when the incident was reported. Was the report filed immediately upon discovery? If not, when was the incident first discovered? Record the date that your team accepted responsibility for conducting the investigation. If there is a significant lapse, explain why this occurred. People are going to want to know why, if the event occurred on January 1, you didn’t start looking into it until August 1.

What happened? Is criminal activity suspected, or is this in internal investigation into possible employee malfeasance? Here is where you will indicate if you are looking for contraband, for breaches of security policy, evidence of theft, or whatever the cause for concern might happen to be.

Where did it occur? Is the incident isolated to a single workstation, or is it a network event?

Acquisition and Preparation

Next, the report goes into the steps taken in preparing the devices and media for examination and how the examination of the materials was conducted. This section of the final report summarizes the details that are in the various examinations logs that were collected along the way. It is not necessary to be quite as detailed here, but it is important that no steps be left out. The reader can be referred to the examination logs for intimate details.

Details that should be included are

• Any actions taken prior to evidence acquisition (such as photographic records, forensic examinations by other departments, etc.)

• How the media where forensic copies were stored was prepared, including what tools were used to sanitize the media

• File names and before/after hash values of disk images examined

• Tools that were used for making images

• Individual steps that were taken during each process

Include times and dates that evidence items were handled and when they were returned to evidence storage. It is essential that everything in the report can be corroborated by the chain of evidence logs and any other documents filed.

Findings

The findings section is not a place for coming to conclusions. This is only where the results of the various tests, examinations, and procedures are reported. As with the preparation stage, it is necessary to document what tools were used and what steps were taken, but the reader can be sent to the examination logs for a blow-by-blow description.

The process used in any given file search should be described, including such details as command-line triggers used to refine the search, search strings used, Boolean operators used, and so forth. Rather than list each and every file found during the search, a summary of findings, including the number and types of files found, is in order. For example, it would be appropriate to say “256 image files were discovered, 128 of which were JPEGs, 39 of which were TIFs, and the remainder were PNG files.” If appropriate, a complete listing of files, complete with file name, path, and MAC data can be recorded in an appendix attached to the final report.

The results of an Internet search would include a listing of any Web sites visited by users on the target system, organized by user. A timeline of Internet activity should be provided as a graphic as well as in tabular format.

E-mail searches should be treated similarly to file searches with some notable exceptions. Individual messages may have trouble standing alone as evidentiary material unless the content contains a real “smoking gun.” In general, e-mails need to be processed and presented in such a way as to provide the entire chain of messages, with each TO and FROM entry intact. It is important to be able to identify which message may have been the initial carrier for specific attachments.

Report Conclusion

The summary is where the investigative team presents its interpretation of the facts. The “how” and “why” parts of the story are filled in (although “why” is rarely an issue in most investigations). As has been stated numerous times, it is not appropriate to hypothesize guilt or innocence of any party. The goal of the investigation is to excavate and present evidence, incriminatory or exculpatory, directly relevant to the complaint issued when the case was first handed over.

At this point, the writer of the report may need to do more than present facts about what was found. For example, as part of the evidence it may be that the examiner discovered log entries indicating that SQL records were accessed by a specific user ID and that a particular sequence of database events was initiated as a result of that access. The general reader is not likely to understand how this implicates the user or exactly what it is that the evidence suggests they were doing. An explanation of why this is relevant is necessary.

Additionally, some steps taken by the investigation team may not seem relevant or logical. An examination of Exchange Server logs reveals a lot to a professional, but the average person won’t even know they exist. Likewise, an analysis of the Windows Registry can be very revealing, but the investigator may need to explain exactly what was being sought and how the registry holds the key to finding it.

As with all other sections in this report, the expression of opinions should be reserved. However, this is the one place in the report where a professional opinion might be required. For example, the evidence might point to the possibility that the user employed antiforensic tools to obfuscate evidence. However, there is nothing remaining on the system to prove such tools were used. It would be appropriate to explain why such an opinion was reached and how it affects the other evidence that was actually found and presented as part of the investigative process.

The conclusion should tie all other sections together. The final report should indicate that the investigation was thorough and complete. If a report leaves the reader asking more questions than are answered, there exists a distinct possibility that the investigation was not completed as well as it might have been.

Chapter Review

1. Describe several aspects of the preparation phase of digital investigation. What types of tasks can be accomplished before an assignment is ever received? What tasks in this phase are specific to a particular assignment?

2. How would you describe the triage process used by a first response digital investigation team? What type of issues are considered, and what are the priorities?

3. Brian Carrier defines five phases of crime scene management. What are those phases, and how do they relate to digital forensics?

4. What impact can poor evidence handling have on whether or not the courts consider digital evidence admissible in court? What document records how evidence is handled as it moves from one stage of the investigation to another?

5. Describe the contents of a final case report package. Be as thorough as possible.

Chapter Exercises

1. Using your favorite word processing application, put together your own template for an evidence chain of custody. Use the description in this chapter as a guide.

2. Based on what you have learned in this chapter, put together a list of files that will be generated by the investigative team throughout the course of an investigation. Decide on a file-naming convention, and itemize the list of files you will create.

References

Beebe, N., and J. Clark. 2005. A hierarchical, objectives-based framework for the digital investigations process. Digital Investigation 2(2):3–10.

Carrier, B. 2003. Getting physical with the digital investigation process. International Journal of Digital Evidence 2(2):2–3.

Kruse, W. G., and J. G. Heiser. 2001. Computer forensics. Incident response essentials. Boston: Addison-Wesley.

U.S. DOJ. 2004. Electronic crime scene investigation: A guide for first responders. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Justice.