Digital Archaeology (2014)

20. Licensing and Certification

There is a battle being fought in the field of digital forensics, and many of the practitioners aren’t even aware that they are an object of the fight. A number of prominent individuals and organizations in the industry have been calling on a set policy regarding certifications. Are they needed? Are they even valuable?

Another obstacle that investigators face in many states is the bureaucratic process of licensing. While not a national issue, there are many states that require independent forensic investigators to obtain licenses to practice their trade. In some states, it is necessary to become a licensed private investigator. This chapter will not be the all-consuming answer readers might hope for, because—for the time being, anyway—there are no answers carved in stone for us to dig up and interpret. What will be covered here is a summary of what to watch for. Since different states have different laws, take care to be specific in your area.

Digital Forensic Certification

For several years now, there have been calls for a standardized approach to certifying professionals in the area of digital forensics. Meyers and Rogers (2004) took an academic approach to the argument in an article published in the International Journal of Digital Evidence. Their stance was that in order to provide standard levels of excellence in the practice, a uniform certification program should focus on three areas:

• Admissibility of evidence

• Standards and certifications

• Analysis and preservation

Assuming that everyone who possessed a certification was able to demonstrate a minimum level of competency in each of these areas, the assumption is that questions about the validity of the investigation process would be significantly reduced and hopefully become a thing of the past. The argument will continue, and in the meantime, we must go on with our work. So for now, this chapter will examine some of the current certification programs and discuss how each might be of significance to the forensic profession.

The certifications fall into two basic categories: vendor neutral and vendor specific. There is a certain value to each type. Vendor-neutral certifications concentrate on concepts that do not vary, regardless of what brand of software or equipment is being used. Vendor-specific certifications test the candidate’s proficiency in using a particular device or product.

Vendor-Neutral Certification Programs

Virtually every professional field has at least one certification program that tests professional qualifications. For example, the CompTIA A+ certification program evaluates the abilities of candidates to perform as computer hardware and desktop operating system technicians. Many organizations hiring help desk and desktop support personnel look for an A+ certification in the candidate’s resume. Several organizations have stepped up to offer varying levels of certification in digital forensics. The ones discussed here are

• Global Information Assurance Certification (GIAC)

• Certified Digital Forensic Examiner (CDFE)

• Digital Forensics Certification Board (DFCB)

• International Society of Forensic Computer Examiners (ISFCE)

• Mobil Forensics Certified Examiner (MFCE)

Some of these organizations and programs offer multiple certification options. If so, the different programs will be discussed briefly.

Global Information Assurance Certification (GIAC)

GIAC offers three different certification programs for the digital forensics professional. Two of those certifications are targeted toward the type of investigations discussed in this book and will be covered in this section. The third, while not directly relevant, may be of some interest. The first of their two forensic certification is the GIAC Certified Forensic Examiner (GCFE). It is targeted toward individuals who perform basic search-and-seizure tasks and electronic discovery. The GIAC Certified Forensic Analyst (GCFA) focuses on a candidate’s ability to collect and analyze data from Windows and Linux computer systems in a forensic manner. It is more suitable for law enforcement or civil computer examination positions. The third exam, the GIAC Reverse Engineering Malware program, tests the applicant’s ability to examine the code of malicious software and back-trace its origin. This exam is beyond the scope of this book

GIAC certifications are acquired by demonstrating a level of professional experience in the field of choice and by passing one or more certification exams. There is no specific training requirement for the exams, although training is offered through the SANS (System Engineering, Networking, and Security) Institute at a charge. There is also a fee for taking the exams.

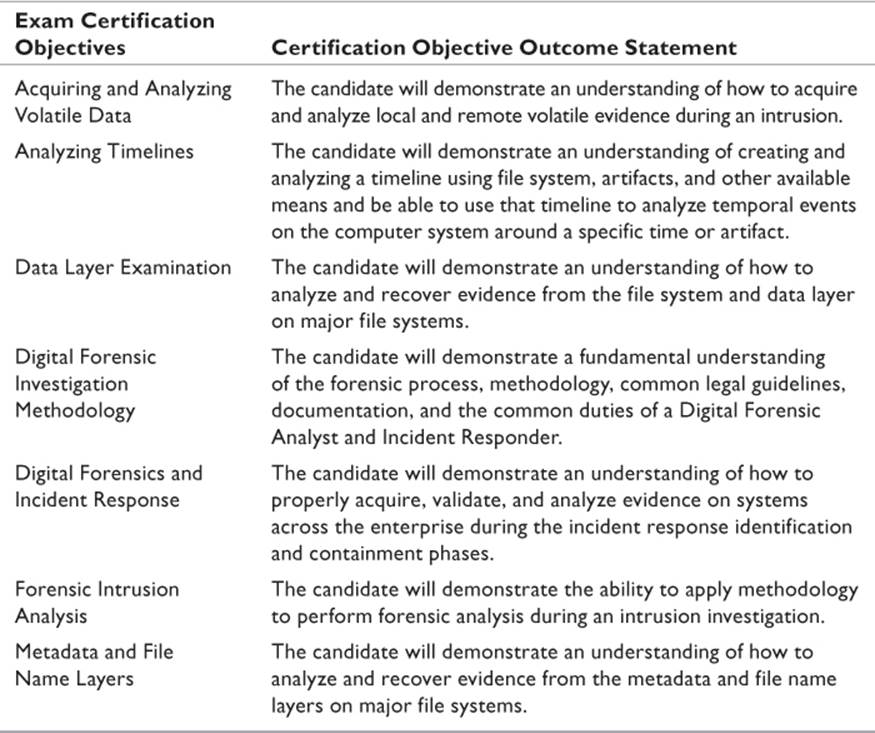

GCFA

Targeted at professionals working in information security who have an occasional need to perform forensic examinations of computers, GCFA is not quite as intensive as its GIAC brethren. Do not make the mistake of thinking that makes it an easy exam. To obtain the certification, the candidate must pass a proctored exam consisting of 115 questions. There is a 3-hour time limit for completing the exam, and a 69% or higher score is required to pass. Each candidate will be presented questions from seven different objective domains (Table 20.1), with equal emphasis on each domain (GIAC 2012a).

Table 20.1 Objectives of the GCFA Certification Program

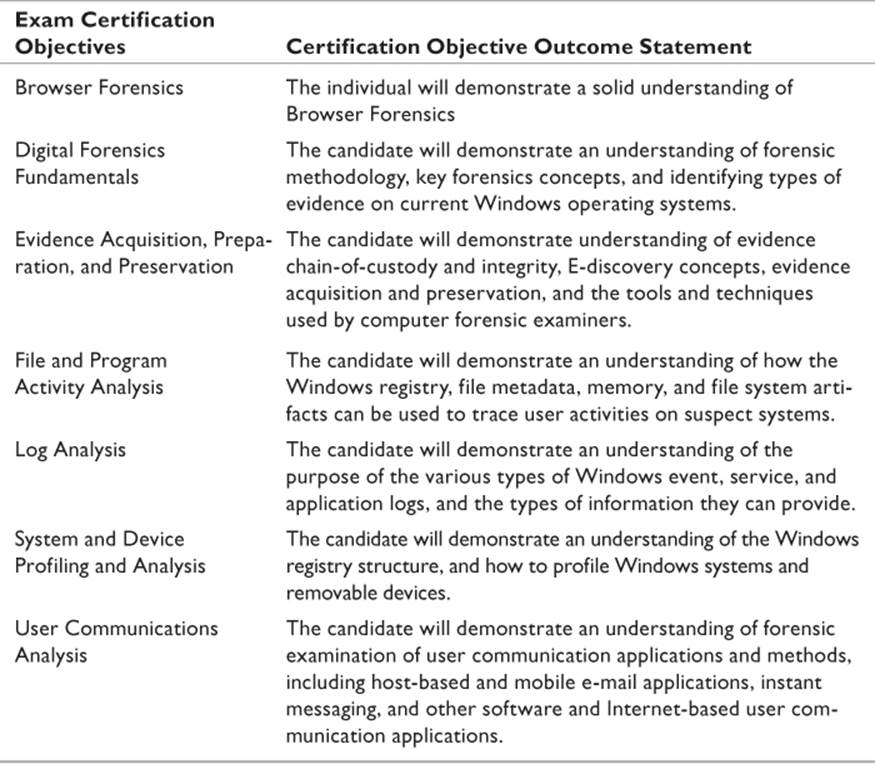

GCFE

The GCFE testing program concentrates on incident response, incident investigation, and intrusion analysis. To acquire the certification, a candidate must pass an examination consisting of 115 computer-delivered questions. Three hours are allowed for completion of the exam, and a passing grade of 71% is required. There are a number of exam objectives (Table 20.2) that will be covered (GIAC 2012b).

Table 20.2 Objectives of the GCFE Certification Program

Certified Digital Forensic Examiner (CDFE)

The CDFE is one of several information technology certifications administered by the Information Assurance Certification Review Board (IACRB). Since it is the only program administered by this organization that targets digital forensics, it is the only one to be covered in this chapter.

CDFE tests a candidate’s basic understanding of digital forensics. The examination covers both the technical (or “hard skills” as IACRB calls it) and nontechnical (“soft skills”) aspects of digital investigation. Soft skills would include topics such as the legal issues facing the forensic investigator and the basics of documentation.

IACRB (2012) lists nine knowledge domains that are tested with roughly equal emphasis on each:

• Law, ethics, and legal issues

• The investigation process

• Computer forensic tools

• Hard disk evidence recovery and integrity

• Digital device recovery and integrity

• File system forensics

• Evidence analysis and correlation

• Evidence recovery of Windows-based systems

• Network and volatile memory forensics

• Report writing

The exam consists of two parts. In order to progress to the second phase of the exam, the candidate must pass the first phase. The first phase consists of a multiple-choice exam built dynamically from a master bank of questions. The candidate is presented with 50 questions, and there is a 2-hour time limit for completing the examination.

Once the candidate has passed the multiple-choice exam, he moves on to the practical exam. A mockup of an authentic forensics case must be analyzed, based on a scenario presented in the case. The examinee has 60 days to create forensic images, analyze the data extracted, and present a formal report that would hold up as evidence in court.

Digital Forensics Certification Board (DFCB)

Of the certification processes covered in this chapter, the DFCB is probably the most rigorous. The two certifications offered by DFCB are the Digital Forensics Certified Practitioner and the Digital Forensics Certified Associate (DFCB 2012). To apply for either certification, a person must already have significant experience in the field of digital forensics to even begin the certification process. A candidate must be able to demonstrate a cumulative level of experience derived by totaling points from the following factors. The DFCB candidate must demonstrate that at least two of the years of experience claimed must have come within the last three years. Requirements are as follows:

• Cumulative work experience (five years minimum) as a manager supervising digital forensic professionals, as a digital forensic professional, or from any other professional discipline in which digital investigation is a part

• Minimum education of an Associate’s degree, with additional credit given for higher degree levels and the number of credits earned in a digital forensics platform

• Additional training from sources such as vendor-sponsored classes, education-for-profit enterprises, and such

• Other related professional certifications

• Other professional experience

To get a more detailed explanation of the process, go to www.dfcb.org/dfcbapplication/login/AssessmentForm.aspx and complete the assessment form. Keep in mind that this is simply the assessment to determine if a candidate is eligible to start the process of DFCB certification. After DFCB completes the assessment, a $100.00 exam fee is required. Once the applicant has been accepted as a candidate, a $250.00 exam fee must be paid.

At this point the candidate is scheduled to take the exam in the next cycle. Exams are administered in the last seven days of every quarter. While waiting, the candidate must submit to a background check administered by a third party. If the candidate passes the exam and the background check, the experience and education claimed in the original assessment form with be verified. Once all of these steps are completed successfully, the person is registered as a DFCB-certified professional.

The exam contains questions derived from seven knowledge domains, some of which are subdivided into subdomains. It is not essential that the candidate be an expert in any one of the domains, but must show general proficiency in all seven. The domains, along with subdomains, are

• Legal

• Ethics

• Storage media

• Acquisition

• Examination analysis

• Mobile and embedded devices

• Acquisition

• Examination analysis

• Network forensics

• Acquisition

• Examination analysis

• Program and software forensics

• Quality assurance, control, and management

International Society of Forensic Computer Examiners (ISFCE)

The ISFCE administers the Certified Computer Examiner (CCE) certification program. The goal of the program is to provide an equitable and vendor-neutral process of verifying the competency of people professing to be digital forensic specialists (ISFCE 2012). In addition to passing a rigorous examination, the candidate also undergoes a background check and application process conducted by the society.

While the process purports to be vendor neutral, it does not ignore the necessity of understanding how software tools do the job they do. The examinee is expected to have a fundamental knowledge of how to use the right tools for the job and to be aware of the capabilities of the various products on the market, both commercial and open source.

To be accepted into the certification process, candidates must demonstrate that they have either completed an authorized CCE Boot Camp Training program, provide proof that they have a minimum of 18 months of verifiable professional experience in conducting digital investigations, or present documentation of a program of self-study approved by the ISFCE board.

Once approved, the candidates begin the testing process, which consists of multiple phases. First, they must pass an online written examination with a score of 70% or higher. If an individual fails the first time, a single retake is allowed. A second failure results in expulsion from the program without an option to reapply.

After passing the written exam, the practical aspect of assessment begins. The candidate is assigned an individual assessor and is given the first of several practical projects. Each project consists of a disk image that the candidate downloads, processes, and analyzes. They have a 90-day time limit to complete each practical exercise, write a detailed report, and submit it to the assessor. Only one opportunity is provided to successfully complete each project. The projects are scored and averaged. An average score of 80% is required for passing the practical portion of the exam.

Mobile Forensics Certified Examiner (MFCE)

The MFCE program is administered by Mobile Forensics, Inc. (MFI). The program recognizes the fact that there is a wide variety of software and hardware tools available to the investigator, and as such concentrates on the process rather than the tool. The certification process is a combination of written exams and practical application of knowledge through the completion of projects. While MFI does offer courses to candidates, it is not a requirement that a person attend these courses as a prerequisite to admission to the certification program as long as the candidate can demonstrate that he or she has successfully completed both a basic and an advanced course in cellular phone data extraction and pass a basic proficiency exam with a score of 85% or higher (MFI 2012).

Once accepted into the program, the examinee will complete six projects and undergo a final examination. Each project makes up 10% of the final score, and the final exam is worth 40%. The candidate must complete each project inside of 14 days, with a score of 100%. The final exam requires a grade of 85% or higher to pass.

Once the testing process is completed, the candidate enters a peer/supervisory review stage. During this phase of the certification process, it is necessary to conduct a minimum of four mobile phone examinations for the organization where the individual is employed. The peer or supervisor assigned to conduct the review will document each case investigated by the candidate and submit a report to MFI. Upon completion of four satisfactory analyses, the examinee will be awarded certification.

Vendor-Specific Certification Programs

The complexity of commercial forensic products gets greater every year. Failing to properly utilize a product almost certainly invalidates the results. It is not surprising that many of the major players in the field offer their own certification programs to test the users’ proficiency. Many of these programs are internationally recognized. There are fees associated with each of the programs, and most require that you demonstrate a minimal level of formal training as well as experience. While there are literally dozens of privately administered programs, there are only a few that I will discuss here:

• Guidance Software

• Access Data

• Paraben

While there are numerous other programs, these three are commonly cited in interviews and online job descriptions.

Guidance Software

Guidance Software’s Encase forensic suites were cited by PRNewswire as a clear market leader (PRNewswire 2011). Whether this is accurate or not, it is certain that the product is a powerful force in the industry. 2011 revenues were up over 12% from the previous year in spite of a challenging economic environment. The company offers two certification programs: the Encase Certified Examiner (ENCE) and the Encase Certified eDiscovery Practitioner (ENCEP).

ENCE

The ENCE certification is targeted toward forensic computer examiners in both the public and private sectors. It tests the applicant’s proficiency in performing forensic examinations using the Encase suite of software. In order to apply for certification, an individual must either undergo 64 hours of authorized forensic training (college credits, generic forensic certification programs, etc.) or be able to document 12 months of professional computer forensic experience (Guidance 2012b).

Testing is done in two phases. Phase I is a written exam. The candidate must achieve a score of 80% or higher in order to pass. Those who pass will progress into Phase II, which is the practical exam. Here, the person is given a set of media to examine and has two months in which to complete the analysis and submit a written report. Phase II requires a score of 85% or higher to pass.

ENCEP

Individuals whose professional responsibilities primarily involve electronic discovery will be better served by pursuing the ENCEP certification. Much of the material covered on the exam overlaps that of ENCE, but is targeted more toward civil litigation and the recovery of materials requested in a discovery motion. As with the ENCE, the exam consists of two phases: written and practical (Guidance 2012a).

The written exam consists of 100 questions drawn from a pool of questions. The candidate must score 80% or higher in order to pass. The practical is somewhat less rigorous than that of the ENCE. For the ENCEP, Phase II consists of a series of scenarios presented in an online environment. Each candidate is allotted 3.5 hours to complete all of the assigned scenarios. A passing score of 80% is required.

AccessData

AccessData may lag behind Guidance in market share, but according to Business Wire, is growing faster and rapidly catching up (Business Wire 2009). Of the commercial certifications surveyed, AccessData offers more individual programs than its competitors. There are a total of five programs:

• Summation Certified Enduser (SCE)

• Summation Certified Case Manager (SCCM)

• Summation Certified Administrator (SCA)

• AccessData Certified Examiner (ACE)

• AccessData Mobile Examiner (AME)

The first three certifications are not targeted toward forensic examiners and will not be discussed. The last two are targeted toward specific digital forensic practices.

ACE

The ACE certification is targeted toward the investigator who works primarily in computer and networking environments. It evaluates the candidate’s proficiency in using AccessData’s Forensic Tool Kit for these investigations. The exam is purely practical and requires that the examinee have access to a computer that has a licensed version of FTK and other AccessData software installed. Once accepted into the program, a candidate is sent an image file to process. Once the work on the image file is completed, the user logs onto a Web site provided by AccessData and answers a set of questions based on the image file processed. There are no prerequisites regarding education or professional experience.

AME

Mobile forensic investigators are better served by pursuing the AME certification. This certification measures a candidates proficiency in using AccessData Mobile Phone Examiner Plus to process portable devices. The testing procedure is identical to that of ACE, and there are no prerequisite requirement for being accepted into the program.

Paraben

Paraben Corporation offers two different certification programs. The Paraben Certified Forensic Examiner (PCFE) program is targeted toward computer and network forensic professionals using Paraben P2 Commander software, while the Paraben Certified Mobile Examiner (PCME) concentrates on the investigation of portable devices. All Paraben certifications require that the candidate sign a statement agreeing to abide by Paraben’s code of ethics.

PCFE

Before a person is admitted to the PCFE certification process, he or she must meet both educational and profession experience requirements (Paraben 2012a). First, it is necessary to complete and pass the P2 Commander Level One class or a qualified equivalent. As of this writing, qualified equivalents had only been recently introduced and none were listed. Second, the examiner must complete and pass P2 Commander Level Two. There are no substitutes for this requirement. Information on registering for either of these classes can be found at www.paraben-training.com/pcfe.html.

The user must also demonstrate and document a minimum of six months professional experience as a digital investigator in any field. Verification can come in the form of a signed statement from a supervisor or previous employer.

Once accepted, the candidate enters a two-phase testing program. The first phase is a proctored online written exam. After passing the written exam, there are four practical assignments to complete. These all involve the examination of forensic images from FAT, NTFS, or ext file systems. All exams, both written and practical, must be passed with a score of 80% or higher.

PCME

Mobile examiners can demonstrate their prowess by obtaining the PCME certification. This program assesses a candidate’s ability to examine portable devices. Prerequisites for acceptance are both educational and experiential. Educational requirements are to pass Mobile Level 1—Mobile Forensics Fundamentals (or an approved equivalent), Mobile Level 2—Advanced Smartphone and Tablet Forensics, and Mobile Level 3—Cellular GPS Signal Analysis. As with the PCFE program, there were currently no equivalent classes listed. Additionally, the candidate must provide documentation of at least six months of experience examining mobile devices.

Once accepted into the program, the candidate must pass a proctored written exam and four practical exams. All exams must be passed with a score of 80% or higher.

Digital Forensic Licensing Requirements

While not obtaining a certification can keep you from getting a job, not getting the proper licenses can get you in trouble. As of this writing there is no licensing requirement on a national level. However, many states have specific licensing requirements for those who wish to open a private practice performing digital investigation. Unfortunately, there is currently no national registry of individual state requirements.

The majority of states that maintain licensing requirements for this profession treat it as though the digital investigator is a private investigator. Some states maintain a separate licensing procedure for digital investigators.

Kessler International conducted a survey in 2008 reviewing the licensing requirements of all 50 states (Kessler 2012). Questionnaires were sent to various state agencies and the results compiled. Only four states failed to respond. The results can be reviewed atwww.investigation.com/surveymap/surveymap.asp. Three states reported having no licensing requirements: Colorado, Idaho, and South Dakota. Alabama, Alaska, and Wyoming do not have general statewide requirements, but enforce licensing requirements in certain cities. Delaware and Rhode Island specifically exempt digital investigators from Private Investigator licensing requirements.

If this isn’t confusing enough, even within states that maintain licensing programs, there are some municipalities that have their own requirements as well. Insomuch as laws can change at the drop of a governor, it would be wise to check with your specific state and locality to determine what the specific requirements in your area might be.

Unlike realtor, bar, or medical licenses, there is little or no reciprocity between states regarding licenses. If you know for certain that you will be practicing in more than one state, it will be necessary to comply with the requirements of each state.

Licensing requirements vary from state to state as well. Some states require minimum educational levels in the field, in-state testing, or some other apparatus by which qualifications can be documented. Other states simply require a background check and a fee. Some of the licensing requirements even mandate firearm training because the requirement is a subset of the private investigator’s license.

The disparity in requirements from state to state prompted the American Bar Association to publish an open letter requesting that licensing for digital investigators and electronic discovery agencies be abolished (ABA 2008). Lack of standards complicated the issue of applying precedents from one state court to similar cases being tried in other states. But for now, the issue of licensing remains one of the most convoluted legal issues an individual or organization faces.

Chapter Review

1. What are three areas of competency that a good certification program evaluates? What different categories of certification program exist?

2. What are two programs that are available from GIAC? How do they differ from one another, both in scope and in requirements?

3. The CDFE tests both hard skills and soft skills. Define each of these terms, and give some examples of each.

4. What certification programs does Guidance Software offer? Which one is targeted for the entry-level examiner, and which is more advanced?

5. Why is it difficult to ascertain whether your state license to practice digital forensics will be recognized in another state? How can you find out for sure?

Chapter Exercises

1. Find three different training providers for different digital forensic certifications. List the classes they offer, and estimate the cost of final certification.

2. Write a couple of paragraphs listing your own state’s requirements for licensing, should you desire to become a private digital forensic investigator.

References

ABA. 2008. Report to the House of Delegates, Recommendation. www.abavideonews.org/ABA531/pdf/hod_resolutions/301.pdf (accessed April 13, 2012).

BusinessWire. 2009. AccessData[R] becomes fastest growing digital forensics software company. www.thefreelibrary.com/AccessData%5bR%5d+Becomes+Fastest+Growing+Digital+Forensics+Software...-a0196137341 (accessed April 15, 2012).

DFCB. 2012. Digital Forensics Certification Board. www.dfcb.org/certification.html (accessed April 13, 2012).

GIAC. 2012a. Certification: GFCA. www.giac.org/certification/certified-forensic-analyst-gcfa (accessed April 13, 2012).

GIAC. 2012b. Certification: GFCE. www.giac.org/certification/certified-forensic-examiner-gcfe (accessed April 13, 2012).

Guidance. 2012a. Encase Certified eDiscovery Practitioner. www.guidancesoftware.com/computer-forensics-training-encep-certification.htm (accessed April 15, 2012).

Guidance. 2012b. EnCE Certification Program. www.guidancesoftware.com/computer-forensics-training-ence-certification.htm (accessed April 15, 2012).

IACRB. 2012. Certified Computer Forensics Examiner (CCFE). www.iacertification.org/ccfe_certified_computer_forensics_examiner.html (accessed April 13, 2012).

ISFCE. 2012. CCE Certification. www.isfce.com/certification.htm (accessed April 13, 2012).

Kessler International. 2012. Computer forensics and forensic accounting licensing survey. www.investigation.com/surveymap/surveymap.asp (accessed April 12, 2012).

Meyers, M., and M. Rogers. 2004. Computer forensics: The need for standardization and certification. International Journal of Digital Evidence 3(2):2.

MFI. 2012. Mobile Forensics Certified Examiner Program. www.mfce.us/ (accessed April 13, 2012).

Paraben. 2012. PCFE: Paraben Certified Forensic Examiner. www.paraben-training.com/pcfe.html (accessed April 15, 2012).

PRNewswire. 2011. Guidance Software and KPMG LLP announce alliance to provide customers with a comprehensive eDiscovery service offering. www.prnewswire.com/news-releases/guidance-software-and-kpmg-llp-announce-alliance-to-provide-customers-with-a-comprehensive-ediscovery-service-offering-78413337.html (accessed April 13, 2012).