Digital Archaeology (2014)

21. The Business of Digital Forensics

One of the lessons a field archaeologist learns early on is that in order to remain in the field, it is necessary to find funding for each project. Since archaeology is rarely a profit center (not if it’s being done legally, anyway), funding must be acquired from sources outside of revenue.

This is true of a large majority of forensic centers as well. While digital forensic can be a very profitable endeavor, a large percentage of people who read this book are more likely to find themselves in the employ of a law enforcement organization or a corporation that is bringing forensics in-house. This chapter will cover four basic topics regarding the business aspects of a digital forensics organization:

• Starting a new forensics organization

• Maintaining an organization

• Generating revenue

• Obtaining an organizational certification

Not all of these topics will be applicable to every organization. Law enforcement is unlikely to generate much revenue. Likewise, it is unlikely that smaller law enforcement organizations and corporate departments will have the financial backing or the incentive to pursue certification for their team.

Starting a New Forensics Organization

Whether the seeds of a new division are planted in a local law enforcement facility or by the CIO of a regional bank, the vast majority of new departments begin with the question, “Can we save money by doing this ourselves?” In some cases, the question is about making money and not saving it, but the core concept remains the same. The startup phase can be considered to consist of two stages. In the initial planning stage, the powers that be brainstorm over the pros and cons of having their own shop. If the pros outweigh the cons, the initial planning stage moves into logistical planning stage.

Do We Build Our Own Shop?

The question of do we build our own shop isn’t as easily answered as one might think. While financial considerations are certainly a significant aspect of this decision, there are also issues of privacy, communications, and competitive edge. Cetina and Mihail (2007) identify several factors to consider when approaching the decision:

• Relative advantage: What is to be gained by the new offering? The implementation of an internal e-discovery/forensics division with properly trained personnel will reduce the organization’s reliance on third-party services in situations where current staff is not up to the task. Eliminating third-party access to private or privileged information significantly reduces the organization’s exposure to threat. More importantly, the risks of noncompliance or unsatisfactory response resulting from reliance on improperly trained personnel will be significantly reduced.

• Compatibility: Having internal staff members who know the needs, the processes, and the structure of the organization means that document searches and investigations can be completed in shorter time periods. Outside contractors spend many hours of otherwise productive time familiarizing themselves with the environment, connecting with the right people, and other preparatory tasks. Internal staff will only have to familiarize themselves with the current situation. Additionally, the organization can rest assured that the staff members are familiar with the infrastructure of the information systems and with the regulations that apply. An outside contractor whose last job was working with hospital systems will have to be diligent to make sure that banking regulations are followed.

• Marketing testability: This is one area where some imagination might be required to apply Cetina and Mihail’s factors to an internal division. However, it can still be done. By assessing the type of information stored in the organization’s file systems along with the past history of incident response, it is possible to apply third-party fees to a time and materials estimate for the value of having internal staff manage those incidents.

• Communication: When assessing a new product, the focus is on communicating the advantages of the product to potential customers. Existing customers are easier prospects because they are already familiar (and hopefully comfortable) with the organization’s products and services. Communication is equally critical to a new department such as the one being proposed. Regulatory agencies will be interested in learning that the organization is voluntarily assuming these responsibilities. Legal issues caused by improper procedure will be dramatically reduced. Risks of penalty will be lower.

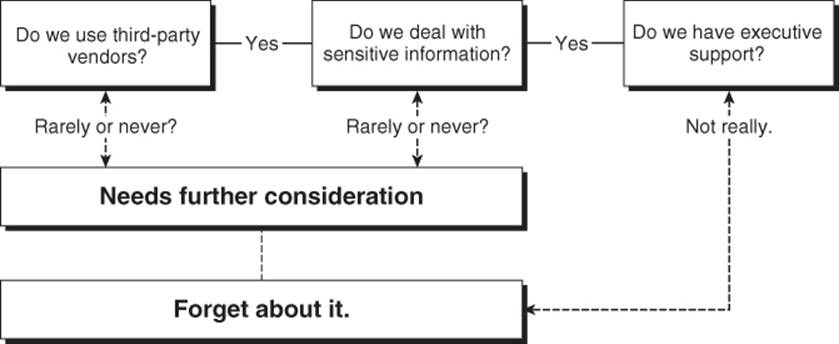

A factor not mentioned by Cetina and Mihail is that of preplanning. Internalizing all aspects of e-discovery and forensic services assures that complete control is maintained by the organization. Accomplishing this task will likely result in the side effect of the forensic team implementing processes and automated data collection tasks regarding computer usage and file system access. In the event of a discovery motion or requirement for investigatory services, the response time will be considerably faster and the process of collection information will be faster. Figure 21.1illustrates a somewhat tongue-in-cheek flowchart for making this critical decision.

Figure 21.1 Should we build our own?

In addition to the obvious benefits, Rowlingson (2004) notes that when an organization makes the effort to create a forensic department, the effort acts as a deterrent to internal fraud. It demonstrates a commitment by executive management to take internal security very seriously. It will only take one or two successful adventures by the new division for awareness of the organization’s new abilities to permeate the corporation.

Part of the planning stage consists of analyzing the scope of services to be offered. A law enforcement agency will be looking to extract criminal evidence from suspect computers, networks, and portable devices. A regional bank will be more interested in assuming e-discovery processes and assuming the ability to take on the responsibility of internal investigations. Ascertaining the type of work to be assumed by the entity will have a direct impact on the costs of establishing and maintaining the organization over time.

It should also be considered that there is a certain amount of risk involved in creating any new organizational entity. Success or failure depends on the organization’s ability to identify and mitigate those risks. Those specific to an expansion such as a new security division carry some unique problems:

• The right people in the wrong job

• Failure to provide sufficient training for personnel

• Not positioning the division for the greatest effectiveness

• Insufficient planning

• Insufficient funding

• Failure by management to “buy in”

Each of these risks will be discussed. It must be assumed that no single risk factor is of greater or of lesser import than any of the others. Consider them as threads of a single piece of fabric. When one begins to fray, the entire structure is in danger of unraveling.

When it comes down to the financial end of the decision making, it is necessary to have a good handle on what it is currently costing the organization to not have the internal capabilities in place. Such costs can be quite evident, as indicated by invoices received from third-party vendors for services rendered. They can also be more subtle. How much is it costing to not provide adequate or acceptable levels of service? Has the organization ever been hit with a penalty for an unacceptable response to e-discovery? If so, that is a cost that must be considered.

The Logistics of Building a Shop

Once the decision has been made to go ahead with the project, it is time to start the real planning. The creation of an entirely new department within the corporate structure is not a venture to be taken lightly. A skilled project manager will be necessary to oversee the process, or the department will fail before it ever takes on its first case. Kerzner (2004) points out that the addition of a new department significantly alters the corporate structure and, as such, also alters corporate culture. In a corporate environment, the simple addition of a department such as this will change the way employees think about security.

This does not have to be a negative thing. Part of the planning process must include some method by which corporate employees are introduced to the new department. If it is presented as another “Big Brother” entity that threatens their livelihood, people are likely to respond in a negative manner.

Wiles and Reyes (2007) identify four aspects of operation for which a forensics department must plan:

• Business operations

• Technology operations

• Scientific practice

• Artistic expression

Business operational planning is a part of logistical planning. Its core services must be strictly defined by executive management, and the department manager must understand and abide by the decisions made here. Conversely, decisions made by management should not adversely impact on the ability of the department to perform its duties. A budget must be planned that is sufficient for department operation, and the manager must work within that budget. Policies developed by executive management must not negatively impact on the ability of the department to protect the organization.

Technology operations for a forensics department are somewhat different than for conventional information technology departments. Specialized equipment is needed and must be budgeted (this is covered in a later section of this chapter). The technology available to the criminal evolves on a daily basis. The technology made available to the department must keep up, or the advantage will tip decidedly in favor of the criminal. Regular refresher training for personnel will be a necessity. While this is technically an aspect of maintaining the organization and not planning it, if this ongoing cost isn’t considered up front, executive management may well decide to drop the project after it is completed.

Acquiring, analyzing, and storing digital evidence requires specialized facilities as well. Secure data storage, secure physical storage, and at least one room isolated from wireless and cell phone signals will be required. Secure telephone lines, alarm systems, dry fire suppression systems, and structural renovation all must be considered.

Scientific practice may superficially appear to be similar to technology, but while the two concepts are interdependent, they are not the same thing. Scientific practice is the ability of department personnel to perform their tasks in a manner that is consistent with accepted forensic practice, is repeatable and verifiable, and is consistently objective. To the corporate department, this reduces the risk that their work will negatively impact the ability to pursue criminal prosecution at a later date. To the law enforcement agency, it is a critical element from the outset. To this end, the hardware and software selected play a significant role. More importantly, the talent and skills of personnel selected must be considered. Executive management plays a key role in this regard with the policies they define regarding operational management of the department.

Regarding the last element of Wiles and Reyes’ list, one may not immediately think of a digital forensics practice as being an artistic venue. Still, intuition and creativity play as big a role as technology when it comes to analyzing the data collected during an investigation. In most situations, the approach taken by an investigator to locate and extract data is an expression of artistic ability. While there is little, if anything, that the project manager can to do plan for this aspect of the department, there is a great deal that executive management can do. Their decisions regarding personnel selection and the degree of control they exert over operations will have a direct impact.

Estimating the Costs of Startup

The initial costs for launching the department will consist primarily of equipment and software acquisition. Another significant expense comes from infrastructure costs associated with the remodeling of office space to accommodate a secure forensic environment and outfitting the office for day to day functionality. This includes network and IT infrastructure necessary for operation. Even though many of these items will exist in inventory, it is still necessary to account for their costs.

The next few pages of this chapter are derived from an actual project on which I worked as a consultant. Please note that while specific brands of equipment and software were used in generating these estimates, it is not my intent, nor the intent of this book, to suggest they are the best solutions. They simply happen to be the ones selected by this particular client. For reasons of privacy, the client’s identity is not revealed, but the costs and products listed are derived from the final report as delivered to the CIO of the company. (Certain proprietary software that could conceivable help identify the client has been removed.) Keep in mind that dollar amounts listed in the tables are those in effect at the time of that effort. Since computer and software costs are such a volatile ingredient, it should be assumed that your actual costs will vary.

Hardware Acquisition

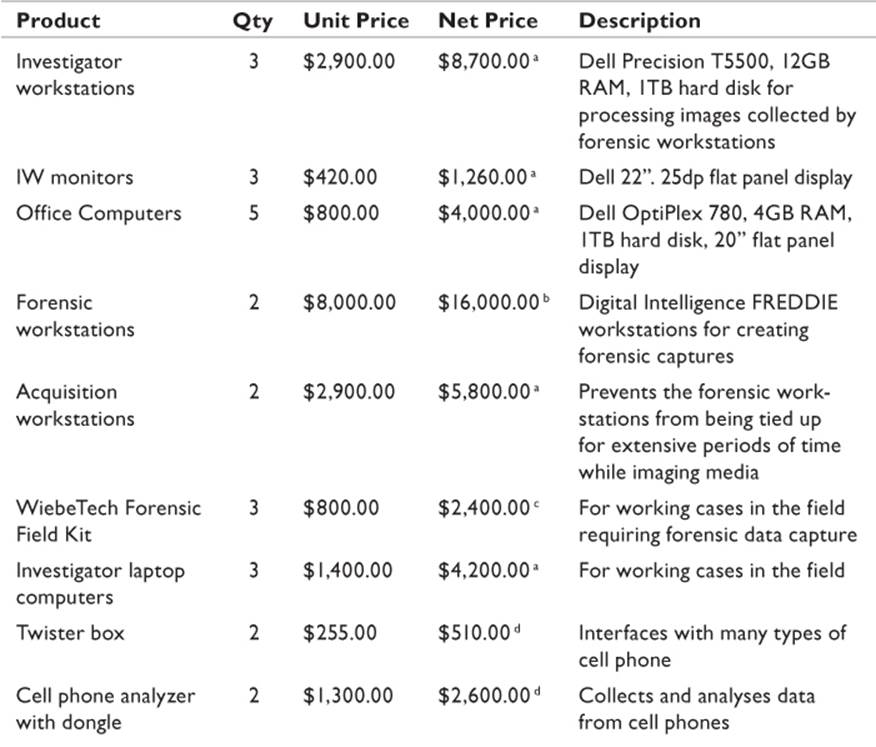

The tasks taken on by a forensics/digital discovery team are unique to the organization and require specialized equipment and software. While the general workstation used by staff for routine tasks can be drawn from a standard desktop image, the investigator workstations have specialized requirements. Likewise, there are some specific software requirements unique to the department. These initial costs are outlined in Table 21.1.

Table 21.1 Hardware Costs

Hardware requirements are relatively significant for the equipment used for forensic tasks. The workstations will perform processor-intensive and RAM-intensive tasks, and a slow machine with insufficient memory will be a handicap. Large amounts of secure storage are required. Evidence storage can be on the network SAN as long as adequate security is configured. Note that in Table 21.1, there are investigator workstations and forensic workstations. The investigator workstations are the computers on which employees will perform routine tasks, whereas the forensic workstations are specific to capturing and analyzing evidentiary material.

All costs were based on the premise that there would be five employees initially assigned to the department. It should be assumed that these numbers must be adjusted for variations in head count.

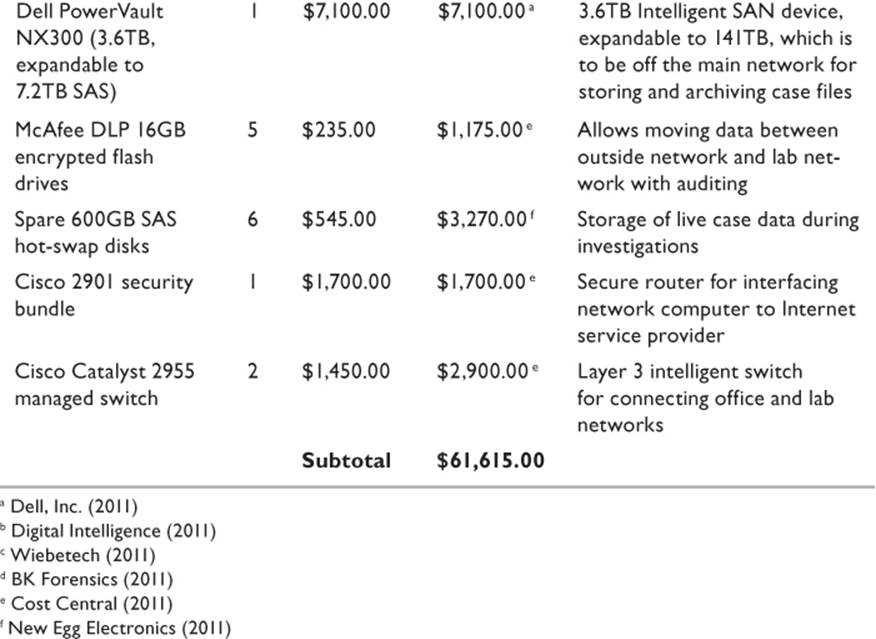

Software Acquisition

The workflow of a forensic department requires the services of several specialized applications as well as conventional office productivity applications. The forensic software selected for this project, shown in Table 21.2, was identified based on its ability to perform functions required by both the forensic investigator and by an electronic discovery specialist. However, to get maximum benefit out of the product, it will require training; it is highly recommend that each of the employees attend the introductory and intermediate classes for the product. The reasons for this include

• Each person will learn to perform tasks in a consistent manner.

• Procedures will be demonstrated by competent instructors.

• Trainees will learn how the application works, making them better candidates as expert witnesses, should the occasion arise.

• Learning proper case procedure will facilitate the capture, analysis, and presentation of evidence in a manner acceptable by the courts, should the necessity present itself.

• A formalized training program is likely to be more efficient, in that it provides incentive for the trainees to meet externally imposed deadlines.

• According to Bishop (1994), employees who receive on-the-job training in specialized fields realize an initial increase in productivity of 9.5%, whereas those who benefit from formal training see an increase of 16%.

Table 21.2 Software Costs

The necessity of the Microsoft Office licenses should be self-evident. The organization already possesses a site license for this product. However, the cost of the software was included in Table 21.2 for comparative purposes. This is also true of the McAfee Total Protection. The Adobe Acrobat is a nonstandard purchase that will be necessary for this project. The ability to create portable documents with security enforced on the front end will be critical to this department.

Facilities Improvement

A dedicated digital forensic/discovery laboratory will be needed for maximum efficiency. It will not be sufficient to simply assign team members to existing cubicles and tell them to get started. Some elements of laboratory design unique to this environment include

• A secure network—disconnected from the corporate network—for forensic and investigative work

• Secure digital storage that is not accessible from the Internet or the internal corporate network

• An evidence storage room that is continuously monitored and accessible only to authorized personnel

• A work room that is suitable for disassembly and reassembly of computers, but that is not accessible by unauthorized personnel

• A work area that cannot be penetrated by external wireless network or cellular telephone signals (for small devices this can be a simple Faraday cage)

Since contracting costs vary so widely from one area to the next, it didn’t seem logical to include any estimated or actual costs in this section. This would become a critical task for the project manager to either assume or to assign to the appropriate personnel.

Maintaining the Organization

Before the first floppy disk is searched, management must make sure that there are a number of policies in place. These must be clearly written out and in many cases signed by the people they affect. Other policies and procedures don’t necessarily have to be documented, but when push comes to shove, it is always better to have things in writing. Among items that should be documented are

• Hiring practices

• Job descriptions

• Investigatory practices

• Evidence handling procedures

• Reporting templates and procedures

• Certification and training policies (including maintenance)

• Organizational chart

• Employee policy handbook

All of these documents should be freely available to anyone with a need to know. That certainly includes those impacted by a specific document, and it also includes any regulatory agencies that may occasionally drop in for a quick compliance check. A signed policy statement is the organization’s best defense against the claim, “But you never told me that was the way we did things!”

There are certain services that are essential to keeping the organization flowing smoothly. In a corporate environment, things like accounting services and human resources are handled by other departments in the organization. This is likely to be the situation in a law enforcement agency as well. However, in a private enterprise, they must be factored into the equation separately. Smaller organizations are likely to outsource accounting services, and possibly even HR. Both require skills that are not mutually inclusive with those of the forensic investigator.

What it boils down to is that, as with any other business entity, a variety of disciplines are involved in order to be successful. In their effort to define a specific management model for a forensic organization, Grobler and Louwrens (2006) identify several critical skills that must be present for a digital forensic operation to enjoy a long-term existence:

• Corporate governance

• Policy

• Legal\Ethical

• Personnel

• Technology

While it is certainly possible that one individual can possess more than one of these skills, it is a rare person indeed who can claim all six of them.

Governance

Grobler and Louwrens tell us there are two factors of corporate governance, strategic and operational. In their efforts to maintain a scholarly approach to their study, I think they missed a critical third component of governance—that of creating and maintaining a corporate culture. Therefore, I am going add that factor to the discussion.

Every business entity needs to have a strategic focus. A mission is identified, and the methods by which that mission will be accomplished are clearly defined. Any business that lacks a focus is a business that is swimming upstream from the moment of its birth. Executive management has to have a precise understanding of the core competencies that exist within the organization. Taking on roles or responsibilities for which competencies do not exist will lead to failure.

Once the competencies are identified and evaluated, a solid set of processes and procedures can be developed that serve as a model of how each case handled by the organization will be managed. That is the function of operational governance. “Making it up as you go” works in the movies. It rarely leads to success in the real world. The approach to operational governance is likely to vary greatly from one organization to another. In a corporate environment where the focus is on internal investigations and e-discovery, the focus is likely to be on patching holes as they are discovered. A security breach costs money, and a quick and confidential resolution is likely to be the first priority. Catching the bad guy and serving justice are secondary. In law enforcement, these goals are completely reversed. The professional forensics agency must be able to shift focus from one priority to another, depending on where the assignment originates.

Operational governance leads directly into the next segment of this discussion. A solid and well-defined set of policies defines the focus of operational governance. Without them, the organization drops back into making it up as they go.

Policy

Probably the aspect of any job that elicits the most complaints is all those rules. Then again, where would we be without them? Real archaeologists have thousands of rules to follow. Where they dig, how they dig, what they can do with what they dig up, how they analyze . . . it goes on and on. And as much fun as a football game without rules might be, determining the winner by pinning a medal on the last man standing flies in the face of sportsmanship. In order to present evidence in a fair and unbiased manner, there are several areas of policy that the organization needs to address.

Hiring

Identify the key positions that must be filled. This is completely dependent on the types of work the organization will take on, the overall budget, and the focus of where those cases will end up. For each position, write a detailed job description identifying the type of skills required. Criminal investigation requires a different skill set than e-discovery response. A person with a solid background in civil litigation can certainly make the move into criminal investigation, but not without a degree of cross-training. There are psychological considerations as well. There are those who cannot handle continual exposure to graphic pornography. If a position involves stressful or strongly distasteful activities, applicants should be warned well in advanced. During the hiring process, a good screening procedure can eliminate candidates who are clearly unsuitable. For existing employees, the job description acts as a foundation for what each person will be expected to do in the course of their employment.

Training

Everybody who successfully navigates the hiring process will have demonstrated that they have the minimum education and experience to perform the tasks for which they were hired. However, the world and technology moves on. If the staff doesn’t keep up, then neither will the business. Most certifications require periodic renewal, which requires attending refresher courses. Your organization needs to have a policy that defines the ongoing training requirements for each position. The policy also needs to specify how such training will be scheduled and who will be paying for it. The organization’s annual budget needs to have a pool of funds from which it can draw for providing the essential training.

Accepting Assignments

It doesn’t seem as if there should be any hard and fast rules for the types of assignments your team takes on. Lack of such a policy can lead to disaster. If you already know you don’t have any people trained in searching iPads, it wouldn’t be a good idea to accept a commercial assignment involving several hundred of them. However, it isn’t just the technology that must be considered. Volume and speed are critical conditions to take into consideration. One person isn’t going to be able to take on a hundred hard disks in any reasonable period of time. An assignment that must be completed in a very short time must be studied carefully. Do you have the resources to do it well? If you can’t do it well, don’t do it at all. A good assignment policy will define several criteria. These include the types of assignments (criminal vs. civil or discovery, etc.) that will be accepted, the policy of the organization regarding rush assignments, what personnel can be used for specific assignments, and the types of digital information that can be examined.

Procedure

Procedural policy can get very complicated if you let it. Here is an area to be as general as possible while still being specific. It is possible to break procedure down into two categories, first response and investigation management. A generalized set of procedures should be written for each category. For example, it would be a good idea to have a set of guidelines that help decide when live response is preferred over hardware seizure followed by a search. Certain practices should be defined and itemized in the procedure. Do you photograph every “crime scene”? For a criminal investigation, this should be standard procedure, but how much does it help in an e-discovery response? What tools will be used for which procedures should be clearly defined. While there is certainly a time and place for using unconventional methods, the conditions that lead to such a practice should be a matter of policy. Methods and approach to case documentation must also be clearly defined.

Evidence Handling

Law enforcement agencies are very familiar with the strict guidelines established by the Federal Rules of Evidence. Every step that is taken during a criminal investigation must conform. Even a minor misstep can result in evidence being rejected by the court. Whether a private enterprise should follow such strict guidelines is a matter of governance. Does the organization have a vested interest in bringing internal investigations before the court? If so, then it is in the best interest of everyone involved if the evidence handling policy is as strict as that required by law enforcement. For a corporate entity, it could come down to a matter of considering each case by its independent merits. Before touching anything, decide on how much damage can be done if the case does wind up in court. And then be prepared for surprises. The evidence handling policy should define how materials are collected, how they are packaged and transported, how they are stored, and how chain of custody is maintained. This is a policy that must be strictly enforced.

Reporting

Reporting is relatively straightforward. Each person who works within the confines of an investigation should have general guidelines regarding case documentation. In Chapter 17, “Case Management and Report Writing,” this subject was covered in detail. In addition to what must be reported, it is necessary to define when it must be reported. What is the deadline from the end of a case to the due date for final documentation? Obviously, larger cases require more documentation, and therefore more time to prepare it.

Data Retention

What happens to data created during the investigatory process once the case is closed? There are several answers to that question, depending on what regulatory oversight is involved. This is an area where legal counsel should be sought. In addition to storing original data, it might be wise to consider how that data will be read several years from now. There is one case in which I am involved that, although I was not around when it was initiated, has been going on for many years. All of the original forensic images continue to be retained in a secure location on the corporate SAN. Throughout the course of a lengthy investigation, followed by an equally lengthy litigation process, it is now going into appeal. Even after the courts have their final say, it will be necessary to hold onto the data for at least seven more years in order to remain within regulatory compliance. One of the pieces of original optical media is so old that there is no longer a device on the market that can read the disk. Therefore, we are also retaining a drive that can read it.

How evidentiary materials will be retained is also a matter for consideration. In the example used in the previous paragraph, the data is stored in two separate locations. The forensic images are on the SAN, as mentioned, while the original media that were collected are stored in an evidence locker. When the time comes, it will be necessary to destroy the information. In criminal cases, the court will order the dispensation of materials. In civil matters, it will be a matter of either an agreement between parties or a court order.

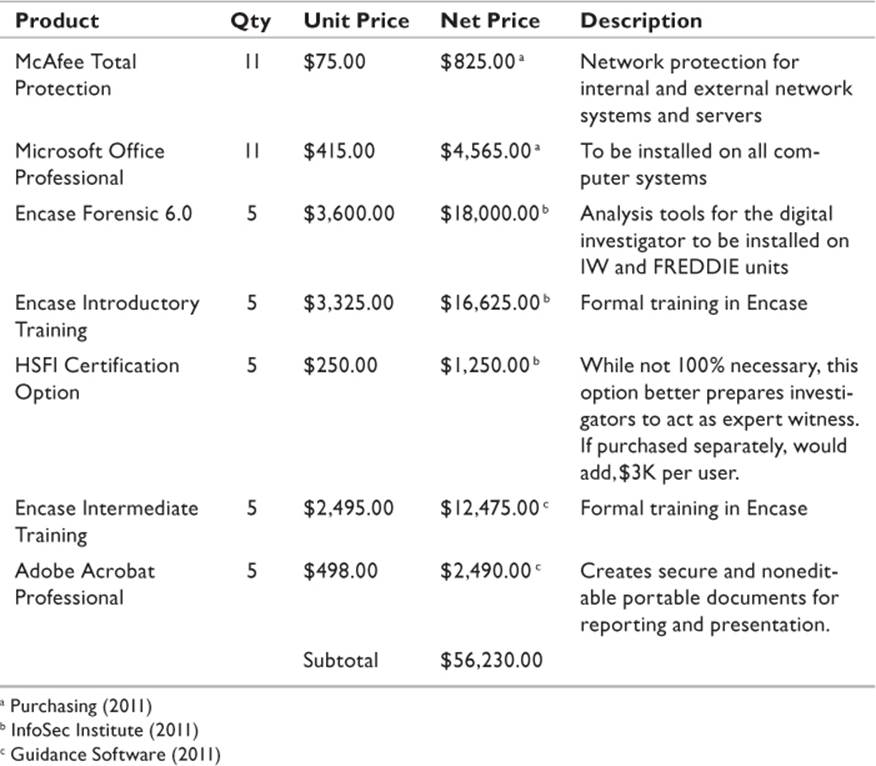

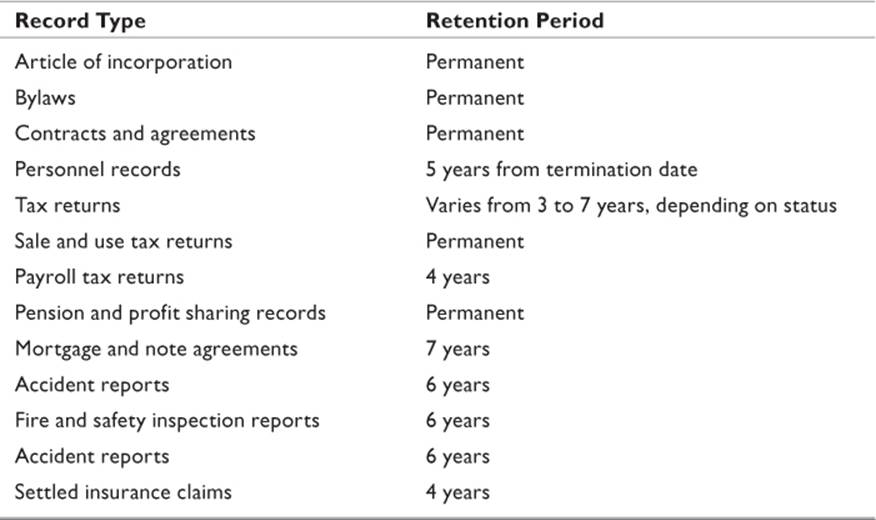

Records of cases that are not evidentiary material are likely to fall under different guidelines. These fall under the category of business records. As such, their retention will be covered under rules defined for the specific type of document. Tax records have one set of guidelines, while payment records have another. Several different organizations have compiled lists of document types along with how long each should be retained. While there is not 100% agreement among all the recommendations, there is general consensus for certain types of records. Table 21.3 is a compilation of recommendations from several government agencies.

Table 21.3 Document Retention Recommendations

Legal/Ethical

There is no point in trying to pretend that legal and ethical issues are one and the same. Truly understanding the law is the domain of the lawyer. However, to be successful, the digital investigator needs to have a rudimentary understanding of the laws affecting the profession. That is why this book has three chapters regarding legal issues. This is not just a responsibility of management. Every employee needs to consider the legal ramifications of every action they take.

Ethical issues require a completely different mindset. If you refer back to the previous chapter on licensing and certification, you will recall that several of the certification programs required that the candidate sign off on a code of ethics. This is but one of the latest efforts of industry players to create a mantra of ethical behavior that will cocoon the industry with an aura of respectability. Nelson et al. (2005) call for a national standard of ethics for the digital forensic industry. While this sounds good on paper, the concept begs the question, who will write these standards? A philosopher is likely to arrive at a different set of standards than a lawyer or a banker. Central to everything is a simple premise. Honesty and integrity are standards that everyone in the industry should bear, regardless of how heavy they might be.

Personnel

As was mentioned earlier in the chapter, one person is unlikely to possess all of the skills and talents required to successfully complete an investigation. When building an organization, you are building a team. Education and training are critical elements in selecting members for that team. Equally critical are personal attributes, such as patience, intuitiveness, and even humor. Never underestimate the value of a cohesive unit. Music lovers all know the stories of their favorite bands who split up because the members could no longer get along.

A digital forensics unit may consist of a single team or it may be several teams, each tasked with specific responsibilities. Regardless of the organizational makeup, in any team, there should be a single team leader. This person is the one who assigns responsibilities and interfaces with clients. In this regard, clients can either be external customers who come to the organization for its services, or they may be various departments within the organization. In a corporate entity, the division manager would be the team leader and would liaison between the unit and other management staff within the organization.

Such a unit as this will require several specialists. The person who is an expert cell phone analyst may be mediocre at hard disk investigation. Network specialists require a completely different skill set than either of these. And people who can do a thorough analysis of a memory image are hard to find. One specialist who is all too frequently overlooked is the person who is responsible for tracking evidence from beginning to end. If it is assumed that each person who handles evidence will be equally responsible for maintaining an accurate chain of custody log, then it can also be assumed that when the chain is broken nobody will be responsible. Regardless of the size of the team, only one person should be responsible for evidence handling. A large organization might have multiple evidence technicians, but if so, there needs to be yet another policy written. That policy should describe the steps to be taken to assure that all evidence technicians adhere to the same rigid procedures.

Occasionally, it may become necessary to outsource certain skills. A small organization that typically concentrates on hard disk acquisition will not be prepared when a case suddenly turns to the Internet. It is very bad policy to bid out each outsourced assignment and pick the lowest bidder. For outsourcing to be successful, there has to be a working relationship between the two organizations. Consider it essential to have a contract in place to define terms and conditions. For each assignment that the contractor takes on, there needs to be a separate statement of work, work order, and purchase order in place. A security agreement that defines how personally identifiable information (PII) is handled is a necessity when dealing with federally regulated industries such as banking, health, and education. All contracts and agreements need to be periodically reviewed and modified as needed. Regulations change.

Technology

The technology of this industry has been the focus of this book. However, there is an art to managing technology, just like there is for managing people. There are a few critical issues to be integrated into a technology management program:

• What technology should we use?

• Is there a solid support infrastructure for each piece of technology?

• How should we handle the testing of products (and upgrades)?

• What will be the decision process for adding new technology?

• What sort of change control should we incorporate to manage and track changes to applications?

What Technology Should We Use?

Simply buying a bunch expensive equipment and software and turning the team loose on it won’t be sufficient. Every new addition adds an element of training, a window for error, and additional potential for obsolescence. That last item is something that frequently gets lost in the excitement of acquiring a new toy. But the successful manager always considers what will happen if the company that manufactures and supports a critical element in workflow suddenly goes belly-up. What will be the costs of migrating the entire organization over to a different product that will perform the same functions?

Deciding on brands and levels of product require a great deal of research. There are several different forensic suites from which to choose and numerous hardware options. Together these all represent a significant financial investment, and most likely an equally significant investment in time and effort. Installation, testing, and training all take time and cost money. You only want to do it once. In researching the different software suites, you are going to discover that some products are very strong in one aspect of the investigation process—such as hard disk analysis—and weak in others—such as telephone analysis. If the plan is to cover all bases, will it make sense to purchase multiple suites? Many organizations do just that. However, keep in mind that this decision will also impact your personnel. It’s hard enough to go through the certification for one product. Do you want the same person to go through it again for another product, or is it better to have dedicated personnel for each one?

Is There a Solid Support Infrastructure for Each Piece of Technology?

The need for excellent support cannot be overstated. Software runs on computers, and computers are notoriously fickle. Most software suites require that support contracts be renewed periodically. Make sure these commitments are kept up. Everything will work perfectly until the biggest case of your career lands in your lap. About a third of the way through your first hard-disk acquisition for the Big Event, your copy of Forensic Disk Copier 3.7 reports a “File Not Found” error or the Massively Powerful Forensic Investigation Unit suddenly blue-screens. Who do you call? The sign of really bad technical support is when, after three hours on hold, the person who finally answers says, “It can’t be our software. It has to be the computer system.” And then hangs up. Good support staff does not hesitate to consider all possibilities and, when necessary, work with other vendors to resolve problems. You know you have good support when the staff of one company willingly works with the support staff of a competitor to resolve an issue.

How Should We Handle the Testing of Products?

Every new piece of software or hardware that is added to the technology infrastructure must be put through a standardized test procedure before it is allowed into the production environment. Larger organizations have test labs set up just for this purpose. Earlier in the book, I mentioned the importance of having test images just for this purpose. If you know exactly what hidden files, deleted files, malicious software, and other nefarious codes exist on the system, then you know when the new piece of software fails to find it. More importantly, if cross-examined on the witness stand about your test procedures, you can confidently answer the opposing counsel’s questions. Only after each new product has been submitted to a consistent testing script, using known data sets, should that product be introduced into production.

The same process applies to upgrades and patches. Anybody who has worked with computers and software for any length of time is fully aware that an “upgrade” is not always an improvement. Review any new upgrades and patches critically, applying the age-old philosophy that “if it ain’t broke, don’t fix it.” Don’t upgrade software unless the upgrade addresses a known issue or adds a new feature that is relevant or critical to your workflow. If a new patch only exists because it fixes a flaw in the FireWire interface—and you don’t own a single FireWire device—why do you care? Don’t install it. Because if you do install it, and don’t go through the process of testing the code change, you open the door for somebody else to claim that your failure to do so is a possible source for errors in your results.

What Will Be the Decision Process for Adding New Technology?

Adding new technology as time goes on requires a good deal of thought and analysis if it represents a significant alteration in work flow or capability. Picking up an extra write-blocker is no big deal. The rules above still apply—test, test, and then test again before you use it—but no major hurdles need to be overcome. Taking on something that changes the way you work requires deeper study. You can’t simply decide you want to suddenly have the ability to start acquiring and analyzing cell phone data. Not only is there a significant investment in hardware and software, but there are personnel issues to resolve. Do you have anyone who possesses the skill set necessary for this latest endeavor, or do you have to go out and hire someone new? What impact is the acquisition going to have on your annual budget? Will the resources be used with sufficient frequency to justify the cost and effort? It is in the organization’s best interest for someone to conduct a thorough study before you wave the checkered flag.

What Sort of Change Control Should We Incorporate?

Change control is a critical aspect of management that often gets overlooked by smaller organizations. Federally regulated organizations are quite familiar with the concept, because it is one of the things that are mandated in many situations. There are two aspects of change control that are necessary. Changes to the way your business works are treated differently in some regards than changes you make to the technological infrastructure. Both are equally critical.

Business Change Control

Business changes are those that affect work flow, the way employees are hired or evaluated, or the way the organization decides which cases to accept and which to refuse. These are just three examples. The list could go on forever. Making changes of this nature require planning. Larger organizations have a change control process that is documented and followed for virtually every modification made to the way it conducts business. It generally starts with someone identifying a need or a problem and then follows a series of events to conclusion. If this series of events is clearly documented and then carefully followed, fewer problems are encountered. The process borrows a lot from the field of project management. For a change to be made, there has to be a clearly defined reason to make the change and equally well-defined penalties for not making it.

You need to understand the current process. Know the purpose for that process and why it exists. Record this information in a change request form. Next, find out what the reasons are for requesting a change in the current process. What is wrong with the status quo, and how will the proposed change make things better? This is part two of your change request. Now, identify all the options for addressing the need or fixing the problem. There is generally more than one solution to any problem. Be certain that all viable options have been considered before committing to anything. Document what those options were, and identify the reasons one solution was accepted and all others were rejected.

If all these questions lead to the answer, “We must change,” then work with internal staff and (if applicable) outside vendors to put together a detailed plan of action. Here is where a skilled project manager becomes a valuable asset. This plan must include testing procedures and scripts, migration into production, and fallback scenarios in case of disaster. Never assume that all will go as well as the sales executive promises it will. Installation, testing, migration, and roll-back plans are now documented as part of the change control process.

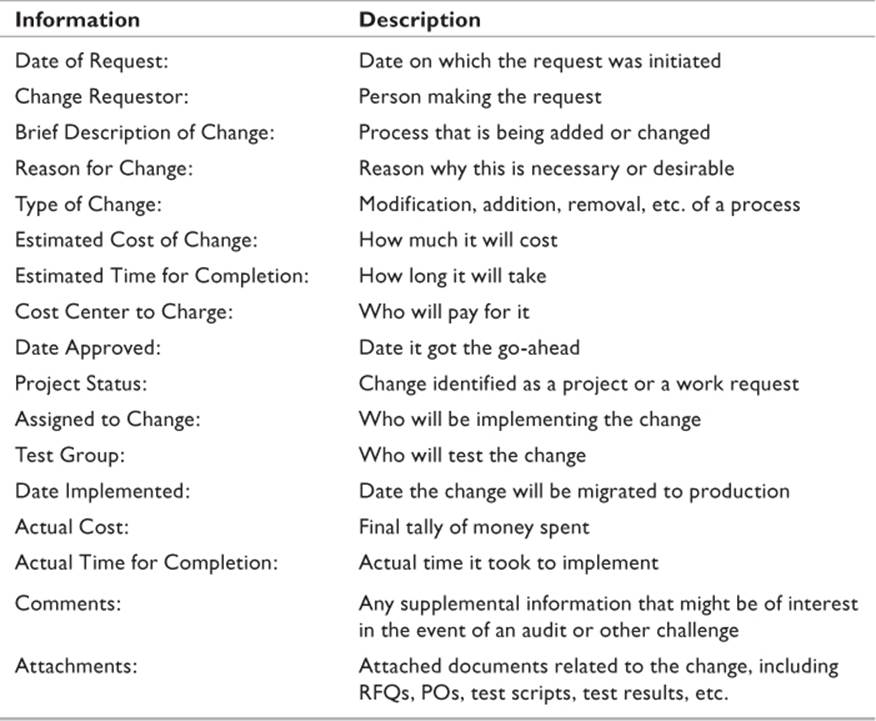

During the process of making the change, document each step taken. Identify individuals involved in specific tasks, and record the time and date that the change occurred. Table 21.4 is an example of what information should be recorded in a standard business change request.

Table 21.4 Sample Business Change Request

Software Change Control

Adding new software should be documented any time the change has a potential impact on the outcome of an investigation. In other words, if you add a new version of Microsoft Office, you probably won’t need to document the changes. If you add new forensics software, upgrade computer or network operating systems, or change core business applications, it is definitely in your best interest to document the changes. As with all other additions, new software must be tested. Therefore, install it into your test environment and give it the usual workout. Then when everyone is satisfied that it performs its job satisfactorily, move it into production.

The same holds true of software upgrades. As mentioned earlier in the chapter, don’t be upgrading simply because there is a new version out. Examine each upgrade or patch to see if it is needed, and then decide whether or not to proceed. A similar documentation process to the one used in a business change request should be used for every software addition, upgrade, or patch that involves network operating systems or core business applications. Some fields to be added to Table 21.4 would be version number, patch number, and release dates for each.

Generating Revenue

Whether the organization is for-profit, nonprofit, or an internal division to a larger corporation, in order to survive, it must maintain a continuing stream of revenue. When the revenue stops, so does the organization. Without revenue, salaries won’t be paid, the electricity and heat will be shut off, and the whole thing comes skidding to a stop. Where that revenue comes from is entirely dependent upon the type of organization. For-profit organizations must find clients willing to pay fees for its services. Nonprofits may depend on a combination of fees and external funding, such as grants or other government funding. The corporate division is entirely dependent on the mercies of executive management to continue funding the department. Since it is highly unlikely that a corporate forensic division is generating any revenue, it is a cost center and not a source of revenue. It is beholden upon the department manager to continue justifying each year’s budget.

For-Profit Organizations

The skills and infrastructure that make for a decent digital forensics organization can be put to use in a variety of ways. There is the obvious service of providing investigation services for clients who are involved in legal matters. This can include working as an expert witness for either side, collecting digital artifacts that will convince a court of the veracity of that side’s claims. For the most part, this will involve civil actions. However, in very small communities, it is not uncommon for law enforcement agencies to outsource certain forensic services to qualified organizations. Each agency will have its requirements for becoming a vendor for forensic services.

A lucrative source of revenue is the provision of electronic discovery services. This presupposes that the organization has properly trained personnel who understand the legal and regulatory issues that apply to specific types of clients. There is an entire chapter in this book specific to that subject. There is also a significant investment in specialized software and massive amounts of storage for each case undertaken.

Data recovery is a service that can provide a certain amount of revenue. This is not quite as significant as other sources, but is one that should be offered. There is a bit more chance involved here, as your organization will often have no control over the media where the lost data is stored.

Network intrusion analysis and penetration testing are two other services that can be offered by the company. Smaller organizations don’t have the tools or the capabilities to handle network intrusions internally. And penetration testing should always be performed by a third party. As with e-discovery, taking on these assignments requires that your organization is equipped and staffed appropriately.

For any job accepted, your organization assumes the mantel of agency for the client. A contract that clearly defines the responsibilities of the client as well as those of your organization is signed by both sides. The contract needs to specify payment terms, including hourly or per-job rates being charged and a payment schedule for remitting payments due. Clear definitions of liability are critical. What risks does the organization assume on behalf of the client? This becomes particularly important any time the courts are involved, whether the case is civil or criminal in nature.

Nonprofit Organizations

To start with, it should be clear that the term “nonprofit” does not mean that the firm doesn’t charge a fee for its services. Nor does it mean that it doesn’t charge more for those services than what it costs to perform them. A nonprofit simply collects surplus revenues and uses them for pursuing its stated goal.

With this in mind, it is easy to apply everything from the previous section to the nonprofit. It can perform any of the aforementioned services for the same level of fees. It simply does not distribute surplus funds to owners or shareholders. If the organization meets federal standards, it may be exempt from income tax.

Two other ways of funding a nonprofit are through charitable donations and through grants. Collecting donations for a digital forensics entity may be a bit of a challenge, but it certainly is not out of the realm of the imagination. It’s a matter of finding people with sufficient disposable income and an avid interest in what you are doing. Former beneficiaries of your services are always a good place to start.

Grants are available to forensics organizations in several places as well. Law enforcement agencies are generally funded under a variety of block grants. A block grant is generally issued by the state or federal government and is intended to cover general expenses. Some of this money can be used to fund a forensics department. Shortly after the financial crisis of 2008, the U.S. Government also started issuing stimulus grants. Some of these grants were administered by the Department of Homeland Security, while others are general grants for local government agencies.

Not all grants are targeted exclusively at law enforcement. Several educational institutions have been funded to establish forensic centers with the two-fold intent of establishing academic programs in digital forensics and to provide assistance to local government entities that do not have sufficient funding to support their own departments. The University of Wisconsin in Platteville received such a grant, as did Purdue University. To find sources of such grants, check with the National Institute of Justice and on the federal government’s grants.gov Web site.

Corporate Departments

Retaining funding in the corporate arena is possibly the biggest challenge of all. Most companies review every department’s budget annually to determine how much funding it will receive for the following year. During that review, the division manager asks for about twice as much as she needs and the Budget Committee gives it about half. However, it is up to the division manager to provide justification for those funds. A forensic division is not a profit center in the vast majority of cases.

If a department isn’t making more money than it is spending, then it somehow has to demonstrate that it is saving the corporation more money than it is costing. There must be a positive advantage/risk ratio or the department will be cancelled. There are several ways to justify the existence of such a department. The implementation of an internal e-discovery/forensics division with properly trained personnel will reduce the organization’s reliance on third-party services in situations where current staff is not up to the task. Eliminating third-party access to private or privileged information significantly reduces the organization’s exposure to threat. More importantly, the risks of noncompliance or unsatisfactory responses to e-discovery demands resulting from reliance on improperly trained personnel will be significantly reduced.

A dollar value can be applied to the services provided by an internal organization. A close estimate of actual costs can be obtained by looking at the company’s past history of incident response, reviewing the volumes and types of information stored, and then getting quotes from third-party vendors for their services in this regard. While these are not “real” charges that the company pays, they do have the advantage of making the value of the department apparent to executive management.

In addition to the aforementioned advantages, Rowlingson (2004) notes that when an organization makes the effort to create a forensic department, the effort acts as a deterrent to internal fraud. It demonstrates a commitment by executive management to take internal security very seriously. It will only take one or two successful adventures by the new division for awareness of the organization’s new abilities to permeate the corporation.

Organizational Certification

In the previous chapter, a great deal was said on the merits of individual certifications. There are also certification programs for organizations. The American Society of Crime Laboratory Directors/Laboratory Crediting Board (ASCLD/LAB) is an organization founded by the Scientific Working Group on Digital Evidence in 1998. The program is an offshoot of a program that has existed since 1982 that has certified laboratories that study physical forensic evidence.

In order to achieve ASCLD/LAB certification, the organization must demonstrate that it meets several criteria:

• Qualified personnel

• Demonstrably scientific procedure

• Strict levels of quality control

• Continued proficiency testing of personnel by outside parties

While these sound like relatively benign criteria, the definitions of these standards fill several hundred pages in ASCLD/LAB’s accreditation manual. Demonstrating the qualifications of personnel is not simply a matter of submitting curriculum vitae. Each individual must pass competency examinations specified by ASCLD/LAB. The results of those tests must be submitted as part of the certification process. The organization won’t even consider a lab that doesn’t meet the Industry Standards Organization’s (ISO) 17025:1999 standards.

ISO 17025:1999 includes supplemental requirements to meet international standards as well as U.S. government standards. They specify testing and calibration standards that a laboratory has to meet in order to qualify. Additionally, it defines minimum conditions that a facility must meet. To meet these standards, the physical facility is inspected and evaluated for its physical security, evidence storage and handling capabilities, and capacity.

ASCLD/LAB measures competency levels in multiple areas. A lab that does not focus on a particular area will not be tested in that discipline. Nor will it be allowed to practice it once certification is awarded. Doing so will get the certification suspended until the lab is recertified to include its new discipline. Following are the areas of investigation at the time of this writing:

• Computer forensics: Examination of digital evidence extracted from computers and computer networks

• Multimedia evidence: Evidence extracted from audio, magnetic media, film, and digital video

• Image analysis: Forensic analysis of digital images

• Forensic audio: Forensic analysis of voice and other forms of digital audio

• Video analysis: Forensic analysis of digital video files

Once a lab has achieved certification, it must undergo an annual conformance inspection. This will be scheduled, and your organization will have the opportunity to prepare for the visit. If during any one of these inspections, it is determined that standards have deteriorated below the minimum threshold, the certification can be suspended or even revoked.

What is the advantage of going to the trouble and expense of obtaining this piece of paper? The value of institutional certification has been a topic of discussion for many years. In 2003, the International Association of Arson Investigators posed the question of how we were supposed to put our faith in the practitioners of a science that few people understand (IAAI 2003). When two “expert witnesses” disagree on not just the conclusion but the actual results of the examination, there is good reason for laypeople—such as the members of the jury—to have reasonable doubt. Admittedly the object of their concern was physical evidence and not digital, but the core concept remains the same. A lab that has earned ASCLD/LAB certification is much more difficult to challenge. Everything about personnel, facilities, and workflow has been thoroughly examined and vetted by a knowledgeable team.

Therefore, for the law enforcement facility, the advantages of certification are relatively obvious. How does it benefit the private sector lab? ASCLD/LAB certification is not limited to labs run by law enforcement agencies. For the organization performing investigations for profit, the advantages are easier to see. When shopping around for third-party services that are critical to a client’s legal well-being, the ASCLD/LAB certification is a sign that the services being paid for will be effectively delivered. The vice president of sales will find it to be an excellent promotional tidbit. Perhaps more importantly, the fact that the facility and all of its employees passed muster for ASCLD is very likely to lead to greater success in providing the support that leads to winning cases for the home team when they reach court. Even better is the fact that solidly documented and irrefutable evidence can keep clients out of court to begin with.

Chapter Review

1. What are some advantages to having your organization build an in-house facility for performing digital forensic investigations? Are there any disadvantages?

2. Differentiate between one-time startup costs and recurring costs. Can you think of any one-time costs that will occasionally have to be repeated?

3. List at least three different policies that a diligent organization must create, publish, and enforce for its employees to follow. (There are far more than just three—be creative.)

4. What are some services that even a full-service organization may occasionally have to outsource? What risks does your organization assume when outsourcing services to another organization?

5. How can an in-house forensic department justify its value if it does not provide services on a for-hire basis? What can it use in place of actual revenue to demonstrate value?

Chapter Exercises

1. Write a brief policy, three to four paragraphs, that defines an employee’s responsibility to securing information in the organization.

2. Write a job description for your evidence handling technician, based on everything you’ve learned in the previous chapters, as well as what is covered in this chapter regarding policies and management procedure.