Pragmatic Enterprise Architecture (2014) Strategies to Transform Information Systems in the Era of Big Data

PART II Business Architecture

Abstract

This part maintains a business focus into an area that few organizations consider because they fail to see the value, whereas the costs are readily apparent referred to as business architecture. It is somewhat shocking that the benefits of business architecture are never questioned when entrepreneurs create an organization with a business purpose. The need to focus on business capabilities from an architectural perspective is inherent in the mindset of entrepreneur as they determine their business model and design the operation. However, once the organization is up and operational, the managers who conduct the day-to-day activities often do not perceive the value of business architecture to address the pressures for change as the organization and business climate evolve.

Keywords

business architecture

business process model

product hierarchy

business capability model

enterprise business review board

business subject matter expert

BSME

hedgehog concept

metrics

sheep

frameworks

guidelines

business SME

business functional architecture

core business capabilities

hedgehog capabilities

ideal business capabilities

outsourcing

core competencies

core competency

personally identifiable information

redundant automation systems

understanding the brain

marketing techniques

direct marketing

CCO

social media marketing

Web-based marketing

mass marketing

customer experience

wordtracker.com

ads

links

banners

business continuity

OCC

Office of the Comptroller of the Currency

US Treasury

second data center

storm track

flood zone

geologic fault line

volcanic hot spot

military and political hot spot

complete suite of applications

sequence of automation systems

business continuity planning

business continuity architecture

business operation

audit

reputation

risk architecture

risk data aggregation

risk categories

financial contagions

comprehensive risk framework

risk model

hedgehog principle

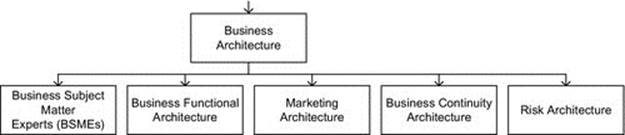

DIAGRAM Business architecture overview.

2.1 Business Architecture and Governance Summary

The number of architectural disciplines with business architecture can fluctuate significantly depending upon a number of factors, such as the number of lines of business, mergers, acquisitions, divestitures, outsourcing and insourcing initiatives, number of IT development initiatives, number of information systems architects requiring business support, and degree of corporate restructuring that may be underway.

If the reader takes one hedgehog principle away from the section about business architecture, it is the flexibility that business architecture has in supplying business subject matter expertise to the parts of the organization that need it most at the right periods of time to properly align activities across the enterprise with the hedgehog principle of the business, including its strategic direction, and priority pain points.

2.1.1 Business Subject Matter Experts

A young man who lives in Manhattan takes his new expensive sports car for a drive through the hills and farmlands of New Jersey. While driving he sees a sheep farm and on the side of the road he sees the farmer mending the fence. Being a talkative fellow the young man pulls off the road to chat with the farmer.

The young man says to the farmer, “I bet you one of your sheep that I can tell you exactly how many sheep you have across these hills.” The farmer somewhat surprised exclaims to the young man that that would be a good trick, and agrees.

The young man with his fingers forming a triangle scans the hills spotted with sheep, and after a moment he concludes that there are eight hundred and thirty two sheep.

The farmer says, “That’s amazing! That’s right, and it looks like you’ve won yourself a sheep.”

The young man then picks up an animal and puts it into the trunk of his car.

The farmer then says to the young man, “I bet I can tell you what you do for a living.”

The young man, surprised, knowing that there is nothing visible on his clothes or in his car that could reveal his profession agrees.

The farmer then tells the young man that he is an enterprise architect by profession.

The young man startled, says, “That’s right! How did you know?”

And the farmer says, “Because that’s my dog you put in your trunk.”

The point of this story is simple. A common theme that you see in large organizations is that no matter how smart IT is, they don’t impress business users when they demonstrate that they don’t really know the business.

Make no mistake about it, business people are the prerequisite for any company’s success. The best business people will command the resources of a company to make it thrive, mediocre business people will generally keep a company afloat as long as there is no stiff competition, and poor business people will cause a company to bleed its capital and market share until it sells the assets of the company to another or is forced to do so in bankruptcy court. The point here is that without good knowledgeable business people, a company does not have long-term survival prospects.

At the same time, we must consider that to better compete, many aspects of the business have been automated with their associated business rules buried within computer programs, allowing companies to hire fewer and less knowledgeable business people. These factors permit companies to handle more business transactions, faster, more consistently, and at a reduced cost.

The challenges that today’s companies face, however, are that the IT people are not business people, to a significant degree they are not business minded, and the further away they are from the revenue producing activities they are, the harder it is for them to quickly relate to the interests of the business. Instead of relating to the business, IT people think of ways of improving their lives with technology, desiring more financial resources to purchase or build additional software and faster hardware that naturally address their own direction and pain points.

That said, spending the resources of business in ways that do not coincide with the direction of the enterprise, or does not address a critical business pain point only serves to squander the limited resources of the business that could have been available to business to better carry out its mission.

In light of these facts, the business sensibilities that are most critical to infuse within the frameworks and guidelines of enterprise architecture are the sensibilities that are not well represented among most architecture teams and less so in most other areas of IT. As a result, it is important that each business subject matter expert (BSME) be just that, an expert in business to convey the hedgehog concept for each area of the business as a steady beat of the drum for each individual to follow.

As such, BSMEs must be extremely knowledgeable about their particular line of business, including awareness of which stakeholders, internally and externally, have interests that must also be taken into consideration. Ideally, it is best to find a BSME that previously owned and operated a small company in the particular line of business, as that would have caused them to be extremely knowledgeable in most aspect of that business.

With this in mind, the next factor is to determine in which business areas there would be an appropriate return on investment for a BSME. If the expenditures and activities of IT to support a particular line of business exceed 10 million dollars annually, which is typically the situation for any line of business in a large enterprise, then a BSME is likely to prove invaluable in either preventing expenditures that were not in alignment with business interests or influencing the activities to achieve a suitably realistic return on investment.

2.1.2 Business Functional Architecture

Companies have numerous business capabilities. Some of them are basic business capabilities that most every company has, such as corporate actions, personnel, finance, accounting, vendor management, procurement, employee communications, IT services, and sales and marketing. The additional business capabilities that would be present are those that are specific to the particular lines of business that the company engages in, and among those there will be core business capabilities.

Core business capabilities are the business capabilities that differentiate your business in its present lines of business. They are not necessarily what your enterprise can do best given its talent and market conditions, but they are the main strengths that support your business that you would not be able to outsource to compete effectively as they may be the reason that customers come to you. In contrast, existing business capabilities that are not core business capabilities have the potential of being outsourced to someone that may do them better.

Business capabilities that do represent what the talent of your enterprise can do best given the market conditions are your true hedgehog capabilities that you can discover and foster as your ideal core business capabilities. These ideal business capabilities is what should drive corporate restructures that would align the assets and interests of the enterprise into what the enterprise can best excel at. If the restructuring is ultimately successful, it will be declared that you have successfully found your hedgehog concept and bravely steered in its direction.

For example, in the credit card industry, the core capability could be limited solely to the assessment of credit worthiness of an applicant. In this situation, the company may perform this business capability better and faster than any of its competition, without possessing an advantage in any other major step within that business such as supporting purchases, billing, or payment processing. In such an example, it can be worth considering the outsourcing the business capabilities that complete the business process but that do not provide a competitive advantage to the enterprise.

When outsourcing business capabilities to an external vendor, organizations must be careful not to also outsource their data. Whether a need for the data is perceived up front or not, organizations must always arrange for the transfer of data back to the enterprise as near real time as is possible within the necessary cost constraints.

Core business capabilities, also commonly referred to as “core competencies,” are initially acquired from the company founders. Core competencies can be developed from within, and they may also be acquired through acquisition:

1. The first objective of business functional architecture should be to recognize existing and potential core competencies, and whether they are opportunities for consolidation or yet unrealized potential core competencies, they should be presented to the enterprise business review board (EBRB) for consideration by executive management.

For example, most large enterprises have large amounts of data that if cleansed of personally identifiable information and proprietary information, may prove to be a source of revenue in the data reseller market:

2. The second objective of business functional architecture should be to recognize a common capability that is redundantly distributed across many applications. In one of the largest educational testing and assessment organizations, common capabilities were found across hundreds of test administration systems. It is the role of the business functional architect to understand the business and how it has been automated across the enterprise, and then present it to the EBRB for consideration by executive management as a potential long-term infrastructure investment.

Simplification by building out a core business capability that can replace disparate versions of redundant automation can be deployed various ways; a core competency may be automated from a global perspective and be shared and centrally deployed, or the code base of the core competency can be shared and then deployed regionally or locally.

Redundant automation systems, however, cannot be completely consolidated until every one of their major capabilities has been taken over by a shared business capability that both supports its business needs and integrates into the business operation. Hence, the management of the enterprise must have interest in considering the long view.

However, architecting a core capability across multiple silo applications, not to mention hundreds or thousands of them, is anything but trivial. As such, the role of business functional architect requires exactly the right combination of experience, a mature enterprise architecture organization comprised the right architectural disciplines, and a mature global application development capability.

For example, a core capability in an organization that makes payments from hundreds of applications to individuals and organizations around the world may be an individual well versed in “global payments processing.”

2.1.3 Marketing Architecture

When this author was a teenager, everyone watched the same few programs on the same few television stations. With the advent of cable television, satellite television, and Internet, choices for media content began to multiply, and today, there is no end in sight to the number of specialty channels that can exist to address the many interests of viewers around the world. My parents listened to radio programs when they were teenagers, and advertisers had what seem like quaint commercials today interspersed within various radio programs, such as “The Shadow.”

It wasn’t that people have recently splintered into having many different interests that can now choose from a large selection of possibilities. It is actually that people have always had many interests and now there are outlets that are satisfying those interests.

Marketing, therefore, had to adapt to the rapid increase of media outlets, ever evolving in an attempt to get our attention. The difference today is that advertising is evolving at the speed of the technologies that we use every day, across our many interests, across the many media.

Today, scientific breakthroughs in understanding the brain are driving marketing techniques over the Internet. Our behaviors and interests are being collected for companies to purchase to predict our preferences for products and services, including when we will want them.

Traditional mass marketing outlets are rapidly falling out of favor as new outlets continue to emerge, attracting our attention to more specialized media outlets that better match our interests. What were once near monopolies, like newspapers and magazines, and nationwide network television and radio networks, are losing subscribers and advertisers by the droves and going out of business.

While global businesses are able to take advantage of the new world of marketing to drive customers to them from across the country and the world, local businesses are finding ways of using the same technologies to attract local customers.

Direct marketing via the US Postal System has mail delivery into a sorting ritual next to the waste paper basket or supply of kindling for the fireplace. The telemarketing industry has popularized telephone caller ID and screening techniques.

Today, marketing must deal with Web site design for computers as well as for smart phones and tablets, and ways to keep them rapidly synchronized with one another.

They must have knowledge of the various techniques for advertising on the Internet, including on search engines, professional networking platforms, encyclopedias, dictionaries, online language translation, and news and social sites. They must have awareness of click stream analysis, real-time feeds that are available from Twitter and Facebook, especially to search for conversations that may be tarnishing your brand with messages that spread geometrically in hours or minutes.

Given the media and information explosion, the growth in high-technology marketing options and emerging sources of information, companies have been creating a Chief Customer Officer (CCO) position with global oversight and direct access to the CEO.

In support of the CCO, marketing architecture is intended to develop standards and frameworks to accelerate implementation of the CCO’s strategy, and to address the myriad of technology issues that must be woven into their global marketing strategy.

In its mature state, marketing architecture is a discipline of business architecture that develops and maintains an overall automation strategy with principles, standards, and frameworks that guide and coordinate social media marketing, Web-based marketing, and the new forms of direct marketing and mass marketing by considering the combination of the latest information available from the behavioral sciences and technology to adapt to the rapid population fragmentation that is occurring across media outlets today.

Advertisements are no longer placed for the greatest number of impressions. Instead, customized messages are strategically placed with the appropriate niche content at the appropriate niche location to get the attention of the precise population that marketing business users wish to target, when, where, and how using proven techniques for getting the attention of the target audience in coordination with marketing activities in various other venues.

Introductory offers for products and services are now more frequently free during introductory periods. Customer experiences are carefully designed by business executives to be carried out across business operational areas and automation across the company. Marketers must use technologies such as “wordtracker.com” to determine the most appropriate words and terms to associate with their Web pages.

As such, the role of a marketing architect requires a broad combination of knowledge and experience in social marketing, Web-based marketing, direct marketing and mass marketing with knowledge of all common electronic communities and numerous electronic communities that are pertinent to the industry, and products and services of their enterprise. They must also have the ability to determine where their competitors place their ads, links, banners, and content.

2.1.4 Business Continuity Architecture

Not long ago any planning for the advent of a major business disruption was an afterthought and was even thought of as a luxury. While many responsible companies recognized early on that a significant business disruption, although unlikely, represented a potential means of going out of business, many of them also realized that even a moderate disruption could cause them reputational damage with their customers that could potentially put them out of business as well.

In the post-9-11 period, more companies have been threatened by terrorism, further raising the risk of business disruption, not to mention the possibilities of loss of life and property damage. This has led to higher insurance premiums for business as well as for federal regulatory oversight to reduce risk to the economy in the event that business centers were attacked.

As a result, minimum standards and frameworks have been established legislatively to facilitate a reasonable rate of recovery of commerce across entire industries. This is particularly true of businesses that have been incorporated under a banking charter as they are regulated and supervised by the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (OCC) within the Department of the US Treasury. The supervision is such that milestones for meeting minimum standards are negotiated with the Compliance Officer of companies, including the scheduling of business continuity tests with representatives from the OCC present to verify that the company has met each milestone. Noncompliance through neglect, mismanagement, or contempt can lead to fines and even a business shutdown.

In addition to ensuring that companies implement specific capabilities within their business operations and data centers, companies are also required to verify that the vendors that they outsource business capabilities also meet similar criteria. However, business continuity has evolved to include a few basics that companies need to know.

In the recent past, it was common to find business users and the automation systems that supported them housed within a data center that was colocated in the same building. Although convenient for the network engineers, this provided an easy way to lose the company’s automation capabilities, business users, and often data in a single event.

As a result, it is now common to separate the location of business users from the location of the data center, as well as to separate business users to multiple locations and have the additional data center strategically distant from the first. This generally translates to the second business office and second data center having to be on a different power grid, on a different coast, and away from the same storm track, flood zone, geologic fault line, volcanic hot spot, and military and political hot spot.

However, having an alternate data center that is safe is just the beginning. Even after IT ensures that there is a high-speed communication link between the remaining data centers and the remaining business offices, the equipment and configuration information must also be present, as well as up-to-date data to allow a disaster recovery process to begin. Probably most important, business continuity must have a well thought through plan.

When considering the variety and complexity of applications that support the automation needs of a particular line of business, the number of applications involved is almost never limited to a single system. In fact, the number of applications involved to support a single line of business end to end is often dozens of all types, shapes, and sizes.

One of the most challenging components of a good plan is the realization that recovering some applications while not others often leaves that particular line of business unable to operate. As such, the sooner that a complete suite of applications are recovered that are used to support a line of business, the sooner that particular business line will be back in action.

Ensuring this level of preparedness requires detail planning, which is planning that we have seen a number of Fortune 100 companies fail to do. The consequence of improper planning the sequence of automations systems within each line of business and their relative priority is that when applications are recovered randomly, effectively no line of business is able to be back in business until nearly all applications have been recovered. Given the resources available to recover applications and the rate at which they can recover applications when a disaster has not occurred, the recovery of all applications in a true disaster scenario can be an unusually long time.

It is like having flat tires on an entire fleet of fully loaded 18 wheeler trucks, and then randomly repairing the tires across all of the trucks, instead of focusing on a particular truck first, perhaps the one with the most perishable cargo. If one were to address all of the tires on the particular truck with the most important loads first, those trucks would be back in service to deliver their cargo with little delay. The alternative is to have trucks and their drivers lingering for a prolonged period of time until the trucks with the most perishable cargo just happened to have all of their tires repaired through a slow random process.

Believing that the necessary equipment and plan are in place is one thing, but testing them to prove it is quite another. The most important reason for frequent testing of business continuity plans is that even great plans are subject to a constant disruption due to the unrelenting onslaught of change.

Change comes in many forms and sizes, and each must be carefully provided for. The smallest change that gets lost can prevent a line of business from being unable to operate. There is the flow of steady change of all types. There are changes in business personnel, IT personnel, and vendor personnel, including their associated access rights to systems and infrastructure. There are changes in facilities, business facilities, IT facilities, and vendor facilities. The only thing that doesn’t change is the steady flow of change.

Automation systems themselves are constantly changing at various levels of their infrastructure, such as their compiled instructions, their interpreted procedural statements, and rules within their rules engines. There are patches to database management system components, operating system components, communications software, and changes to configuration parameters for each. There are updates to drivers, new versions of software, as well as changes within the network infrastructure, security infrastructure, and performance monitoring infrastructure. In addition, there can also be changes in business volume, resulting in changes to data volume and resulting in changes to system load and total available system capacity.

As a result, business continuity planning must regularly test alternate work sites to ensure that business personnel have access to telephone services, Web-based services, communications links to data centers, access to application systems, communications links to vendors that participate in their business process, and access to third-party application systems with the appropriate bandwidth from the appropriate locations.

Each location must have personnel that possess the appropriate instructions and technical expertise to troubleshoot when those instructions fail, not to mention the business personnel to operate these capabilities. Also present at each alternate site must be a reasonable set of spare parts and equipment to troubleshoot and operate the needed capabilities.

As such, the role of a business continuity architect requires a broad combination of knowledge and cumulative experience about the business operation. They must be intimately familiar with the change control process for each type of operational component that can change, which they need to audit periodically between tests.

The business continuity architect in business architecture must work closely with the disaster recovery architect in operations architecture to identify the production assets that support each inventoried infrastructural capability and business application, including databases, networks, operating environments, and the servers associated with them.

In collaboration with the disaster recovery architect, the business continuity architect must ensure the most orderly and coordinated process possible so that business operation recovery occurs in a corresponding recovery of the correctly prioritized IT automation systems and infrastructure. The business value of bringing a line of business back online sooner to serve customers can make a big difference to the reputation of a given enterprise.

2.1.5 Risk Architecture

Risk architecture, also referred to as risk data aggregation (RDA) in the banking industry, is a means of defining, gathering, and processing risk-related data to facilitate measurement between company performance against the levels of tolerance the company has toward each category of risk.

One of the most significant lessons relearned in each global financial crisis is that the scope of information under consideration was inadequate to establish appropriate preparedness. Each time, organizations lacked the ability to aggregate risk exposures and identify concentrations quickly and accurately at the enterprise level, within lines of business and between legal entities. Some organizations were unable to manage their risks properly because of weak RDA capabilities and risk reporting practices. This had severe consequences to these organizations and to the stability of the global financial system.

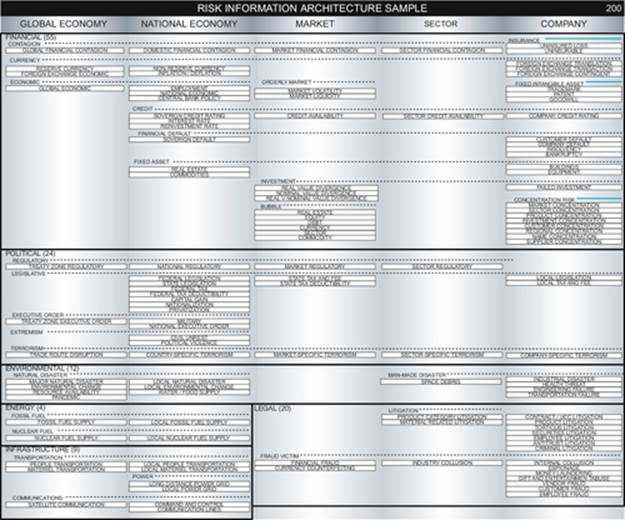

Every enterprise has a particular tolerance for risk and strategy for managing it, although few enterprises have a global view of the risks that influence their economic condition. The role of risk architecture is to develop and maintain a framework of the various categories of risk that can affect an enterprise from the perspective of a global economy, national economies, market economies, industry sectors, and individual companies, including creditors, insurers, customers, vendors, and suppliers.

The role of a risk architect within business architecture is to maintain such a framework and track the various tools, techniques, and vendors that offer risk measuring and tracking techniques.

2.1.5.1 Routine Risk Categories

The areas of risk that are commonly addressed by an enterprise involve financial, political, and legal risks.

Financial risks are usually measured by analyzing investments and credit markets, often using insurance to help mitigate those risks. A moderately more advanced enterprise may evaluate their global exposure to customers and insurers, while a relatively advanced enterprise will monitor the effect of contagions across the various financial markets with a good degree of preparedness to react to recognizable events.

2.1.5.2 Financial Contagions

A contagion is generally understood as a price movement in a market that is the result of a price movement in another market, where the secondary price movement exceeds the threshold that would be considered a comparable price adjustment when based upon an accurate understanding of the underlying fundamentals. Market knowledge and understanding, particularly knowledge about a specific industry or company, is highly asymmetric. Some individuals simply know more or their background allows them to intuit more information than what was communicated publicly.

The types of contagions relate to the ways that they can be initiated, such as significant informational changes about sector or company fundamentals, significant changes in the credit market or market liquidity, a significant unrelated market opportunity, or a simple portfolio adjustment involving large positions involving specific securities.

The market participants usually include informed traders/investors, uninformed traders/investors, portfolio managers, and liquidity traders including program trading automation. The degree of contagion is determined by various market pressures and the buildup of anticipated changes in market direction, but also informational asymmetries and the reaction across less sophisticated emerging markets exacerbate contagion. This is not to say that contagions only represent downward trends, as contagions can also represent an upward movement that attracts mass appeal.

For example, the life cycle of a contagion related to a change in information is often described as new information reaches informed traders/investors whereby then uninformed traders/investors react to the adjustment, thereby amplifying the price movement and volatility. Similarly, liquidity traders, who trade irrespective of fundamentals, can inadvertently trigger uninformed traders and investors to incorrectly attribute price fluctuations as having been initiated by informed traders/investors.

2.1.5.3 Comprehensive Risk Framework

The most advanced enterprises monitor the cascade effect of contagions from the global economy, national economies, market economies, industry sectors, and individual companies to their enterprise, while monitoring a wider array of risk categories, subcategories, and then approximately 200 distinct subject areas of risk depending on the particular lines of business and industries their enterprise operates within.

Some of the risk categories that these risk subject areas belong to include:

- financial risks,

- political,

- environmental,

- energy,

- infrastructure,

- legal,

- informational,

- psychological,

- technological, and

- business.

As an example, the infrastructure category can contain subcategories, such as:

- transportation,

- power, and

- communications.

As an example, the power subcategory can contain distinct subject areas of risk, such as:

- long distance power grid,

- metropolitan power grid, and

- local power grid, power substations and lines.

The value of a risk framework is that it gives the enterprise the ability to consciously determine which categories and subcategories it wishes to monitor, measure, and prepare for.

2.1.5.4 Risk Model Steps

An example of the steps that can be used to approach a comprehensive risk framework includes:

- Identification of stakeholders for the following areas

i. Enterprise risk management (e.g., financial risk, cyber security, operational risk, hazard risk, strategic risk, and reputational risk)

ii. Investment risk management (e.g., portfolio management)

iii. Compliance risk management (e.g., treaty zone, national, and subordinate jurisdictions)

iv. Legal risk (e.g., legal holds by category by jurisdiction)

v. Regulatory risk (e.g., RIM and regulatory reporting by jurisdiction)

vi. Business risk management (e.g., M&A, product development, economic risk, insurance risk, vendor risk, and customer exposure)

- Review of risk framework

i. Identify which risk areas in which each stakeholder perceives value

ii. Determine unambiguous scope and definition

iii. Present an information architecture (IA)-driven framework for assessing them

iv. Identify indicators of those risks

v. Identify sample sources (real time, near real time, and batch)

vi. Propose a scoring framework

- Present opportunities for developing a customized IA-driven model

i. Propose a process with which to evolve

1. source discovery

2. source evaluation

3. source integration

4. scoring

5. analytics

6. forecasting

ii. Identify services that can be offered enterprise-wide

iii. Identify services that can be offered externally

iv. Identify where analytics and forecasting models can be used enterprise-wide

v. Propose a change control refresh process for redeployment of forecasting models

- Technology framework

i. Forecast model technologies

ii. Reporting technologies

iii. Data mining technologies

iv. Mashup technologies

- Data persistence technologies

DIAGRAM Risk architecture (sample).

2.1.6 Business Architecture and Governance

Traditionally, the role of business architecture has been to develop business process models, product hierarchies, and business capability models, all with their corresponding taxonomies and business definitions:

- Business process models are diagrams that illustrate the flow of steps that are performed. At a high level, they may depict the sequence of departments that support a line of business, or at a low level, they may depict the steps that are performed within a particular business capability found within a particular department. Business process models should also depict a consistent taxonomy.

- Product hierarchies are taxonomies, usually shown in diagrams that illustrate the various ways that products and services are rolled up into subtypes and types of products and services by the different constituents of the enterprise. In a large enterprise, there is sometimes a different product hierarchy for marketing, versus sales, versus accounting, and versus legal.

- Business capability models have been illustrated in various ways, but we prefer the forms that most represent a hierarchy of business capabilities that are most similar to a functional decomposition that starts at the top. This method establishes a taxonomy starting with the overall industry, or industries, of the enterprise (e.g., insurance and banking) and then decomposing them into increasingly smaller more numerous business capabilities (e.g., property and casualty, health, life, retail banking, wholesale banking, and dealer banking) eventually down to individual services that support the business capabilities of the enterprise.

While this has its uses in facilitating communication using a shared set of terms and concepts, when limited to these activities, business architecture does not realize its full potential. In the modern enterprise architecture, business architecture must also help the organization adapt to the evolving marketplace, address the needs and expectations of existing and future customers, counter the activities of existing and emerging competition, look to adopt innovations in technology that can transform business, and comply with the evolving regulatory landscape.

To best manage the extended capabilities of business architecture, it can be useful to create an EBRB to facilitate discovery and recommendations regarding a coordinated global business strategy. The enterprise architecture review board would address the following needs:

- determine the most appropriate team of BSMEs necessary to support the business topics that are of great strategic importance to the enterprise or line of business, staffing periods, staffing levels, funding levels, and staff selection;

- assess the efficacy of BSMEs supporting the other areas (e.g., information systems architecture, operations architecture, global application development, and local application development teams)

Staffing of BSMEs also works well as part of and within information systems architecture, as we have done because we did not have official control of business architecture within our area which encompassed the banking lines of business. However, as a coordinated effort across the enterprise, it could better focus on the hedgehog concepts that best define the enterprise and each line of business.

As with the other disciplines of enterprise architecture, the disciplines of business architecture must have readily identifiable metrics that can measure the productivity of each architectural discipline and each individual within business architecture. Together, metrics and planning will provide the necessary lead time in preparing management when to increase, decrease, or replace resources.