Fire in the Valley (2014)

Chapter 10

The Post-PC Era

The introduction of the iPad was a huge moment. As soon as I saw Steve take that thing and sit down in a comfy brown leather armchair and kick back and start flicking his finger across the screen, I tweeted, “Goodbye, personal computer.” Because I recognized that moment as the beginning of the end.

Chris Espinosa

When Steve Jobs returned to Apple in 1997, both he and the company had changed. But the industry itself was changing, and computer companies that wanted to survive were going to have to deal with the new realities.

The Big Turnaround

When Steve came back to Apple, he told me that Microsoft had won the PC battle and that was irreversible, over and done with. But he thought that if he could get Apple healthy enough to persist until the next major tech dislocation, Apple could win at that.

-Andy Hertzfeld

Apple was a company in dire trouble, struggling very publicly for survival. Its already small market share was eroding, developers were building applications for Macs second if at all, the stock was dropping, and nobody seemed to have a plan for changing any of that. In 1996 Business Week headlined Apple’s troubles as “The Fall of an American Icon.”

But Apple wasn’t simply short of cash. It was in an existential struggle to rediscover its identity and to find relevance in the market.

Even before the Mac, Apple had distinguished itself from the rest of the market by virtue of a greater emphasis on design and graphics and top-to-bottom control of the computer’s hardware and software. But Apple’s "thinking different" was a double-edged sword. The design sense and the coherence of a single-source model were advantages. But the proprietary approach frustrated third-party developers and premium pricing kept Apple’s market relatively small. Apple had defined itself as a niche player in a market that was increasingly nicheless. Microsoft had kept improving Windows, to the point where most consumers couldn’t see much difference between a Mac and a PC—except for the price. Windows was undermining Apple’s positives, and the negatives were looming larger.

Retaining its identity and relevance were both critical because while an Apple that tried to be a me-too company would fail, so would an Apple that remained marginalized by its increasingly undesirable differences.

Apple also suffered from internal problems, including lack of focus. “[John Sculley] never really did any technology transitions,” Chris Espinosa recalls, “and Michael Spindler had so many long, flat gestation periods, investing in everything, that he starved everything and nothing ever really took off. I think…that they thought too strategically and too abstractly about technologies and markets, and they took their eye off the ball of ‘real artists ship.’ That what matters is the product that you put into people’s hands.” Jean-Louis Gassée concurs: “They had the wrong leadership in software. And also the culture had become…for a while it had been soft.”

But leaders can lead only in a receptive environment. “John Sculley did a lot of great things,” Espinosa explains. “He came into a company that was headed south fast, and he got it on a firm bearing. One of the problems with Apple from 1985 through 1997 when Steve came back is not that we had poor leaders. It’s that we had extremely crappy followers…the culture of Apple had been designed to follow Steve, and Sculley wasn’t Steve.”

But Jobs, too, had changed in the intervening years.

Espinosa was leery of Jobs when he returned: “I remembered my experience on the Mac team fairly vividly, and frankly, I didn’t really want to create it again. So I hid out in developer tools.”

But Espinosa soon found that he, at least, needn’t fear Jobs’s outbursts. “He was extremely congenial [to me]. I kept hearing the terror stories of the elevator interviews and the screaming fits, which were the good old Steve. But I got the general feeling that those were kind of for show—that it was him exercising reputation maintenance. You know, that used to be an uncontrollable part of his character, and I got the feeling, in later years, that it was an act that he could put on when he needed to. I saw much, much more of the gentle, appreciative, wistful Steve in his later years.”

Most crucially, Jobs had become more effective. The Pixar success, and his role in supporting the Pixar crew and then in negotiating deals for their work, had impressed observers. And there was the money: billionaires tend to be taken seriously. “He was,” Espinosa points out, “the most successful studio CEO since Samuel Goldwyn.”

Legitimacy

But as much as Apple and Jobs had changed, the industry had changed even more.

When Jobs left Apple in 1985, the personal-computer market was less than a tenth the size it would be by 1997, when he returned.

Remember that Apple ad welcoming IBM? It was the one that began, “Welcome, IBM. Seriously.” It got some attention when it ran in 1981, acknowledging that IBM’s entry brought legitimacy to the personal-computer industry. What wasn’t widely recognized even at the time was that the ad channeled an edgier ad from an earlier era. When IBM entered the minicomputer industry a generation earlier, Data General CEO Edson de Castro commissioned an ad that read, “They Say IBM’s Entry into Minicomputers Will Legitimize the Market. The Bastards Say, Welcome.”

That ad never ran, but the sentiment was clear. De Castro was saying that Data General didn’t want to be legitimate. It didn’t want to be IBM. That’s akin to what Jobs was conveying in 1984, when he told the Mac team, “It’s more fun to be a pirate than to join the Navy.”

But legitimacy had won out. There were no more bastards, no more pirates. At least not making personal computers. As a consequence, the computers themselves were becoming commodities.

It seems rapid in retrospect but felt slow as it happened. The GUI—created at PARC, brought to market by Apple, and made essential by Microsoft—made computers easy enough for anyone to use. The electronic spreadsheet, created by Dan Bricklin and Bob Frankston and made essential by Lotus, became the killer app that got personal computers into every business. The IBM name, as it had before, made the purchase of personal computers justifiable to the corporate numbers people. Personal computers had achieved legitimacy.

And what was legitimized was specifically personal computers. Putting a computer on an employee’s desk required new thinking about job requirements, budgeting, internal tech support, maybe even new desks. It challenged entrenched company thinking.

But by 1997 that battle was won. The legitimization of the personal computer, ironically, even drove IBM out of the market. Although IBM had legitimized the business by entering it, “then the dragon’s tail flopped,” as Jean-Louis Gassée puts it, “and IBM got maimed.” IBM had more experience selling computers than anyone else, but it was experience in selling computers one at a time, experience with premium pricing and with strong support. None of that matched well with selling generic boxes off the shelves at Walmart.

In the interim, while the market was expanding by a factor of ten, Apple’s market only tripled. Apple executives could do the math. They were trying to keep the company relevant. Chris Espinosa was there through it all, and reflected on it later:

“I remember [John Sculley] talking about ‘technology S-curves’.… The idea was that a technology would have a long, flat gestation period and then a sudden period of hypergrowth, and then it would top out as the market got saturated or the technology got mature. And at that point the technology in the market would really cease to be interesting, and if you were a company that had bet everything on that technology…you were eventually going to get picked to death by the clones.

“So in order to be a constantly innovative company, you needed to stack up those S-curves. While you had one product that was in a vertical growth period, you had to be developing other products in that long, slow, flat gestation stage that would take off on the next S-curve.

“That was his theory,” Espinosa concludes. “He couldn’t implement it.”

The iCEO

In this environment began the turnaround year for Apple. Most of the changes Jobs implemented had been planned on Gilbert Amelio’s watch, and many had been the ideas of chief financial officer Joseph Graziano, but Jobs made them happen. He shut down the licensing program, which had come too late and had allowed clone makers to cut into Apple’s own sales, as Gassée had feared. Jobs laid off employees, dropped 70 percent of the projects, radically simplified the product line, instituted direct sales on the Web, and stripped down the sales channel.

Most of the decisions ruffled at least some feathers, but one move shocked the Apple faithful and drew boos from the crowd when it was announced at Macworld Expo in January 1997. As Jobs stood on stage, the face of Bill Gates appeared on the enormous screen behind him, looking down like Big Brother in the movie version of George Orwell’s 1984. Jobs announced that Microsoft was investing $150 million in Apple. Jobs recovered by assuring the crowd that it was a nonvoting stake. The investment gave Apple an infusion of needed capital and the good public relations of the endorsement of Microsoft, but Microsoft exacted a heavy price: the rights to many Apple patents and the agreement that Apple would make Microsoft’s web browser its browser of choice. Microsoft was enlisting Apple in its war to control the key software used to browse the Internet.

In the same year that his image was looming ominously over the Macworld show, Bill Gates started the William H. Gates Foundation with an initial investment of $94 million. Later renamed the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, Gates’s further investments soon grew it into one of the largest private foundations in the world, focused on enhancing healthcare and reducing extreme poverty internationally, as well as expanding educational opportunities and access to information technology in the United States.

Within three years Gates would step down as CEO of Microsoft, turning over the reins to his old friend Steve Ballmer. In the ensuing years he would ease himself out of any role at Microsoft to devote himself full time to the foundation. But in 1997, Gates still seemed like the enemy to the Apple faithful.

Despite the plan laid out in the earlier Macworld keynote address, Jobs didn’t retire the Mac operating system. Instead he folded the NeXT technology into an improved OS that was still Macintosh. It would be easy to think, knowing Jobs, that the whole NeXT acquisition had been a Machiavellian scheme, but it wasn’t that simple. Jobs was not at all convinced that Apple could be saved when he sold NeXT. He unloaded the 1.5 million Apple shares he got in the NeXT deal cheaply, convinced that the stock wasn’t going up. “Apple is toast,” he said to a friend in an unguarded moment. But within months Apple had gone from a zero to a one in Jobs’s mind, and he threw himself into saving it. The board was willing to give him anything he wanted, repeatedly offering him the CEO job and chairmanship. He turned them down but still ran the company dictatorially, inserting himself into any department at any level he thought necessary, under the title of interim CEO. He wasn’t getting any significant compensation and, having sold his Apple stock almost at its lowest point, wasn’t getting any financial benefit from Apple’s success, either.

Merging the NeXT operating system with Apple’s was an extremely complicated and chancy endeavor, like fixing an airplane engine while flying. And it took time: it was three years before what was called OS X finally came out.

Meanwhile the hardware line was also being revamped. Conceding that personal computers had become commodities, Jobs embraced that model and used commodity features to sell computers. The iMac and the new desktop Mac computers that came out in 1998 and 1999, designed by Jony Ive, brought color and a sense of style to computers to a degree that had never been attempted before. The market ate them up. The iMac not only sold well; it became the best-selling computer on the market for several months running. Apple began making consistent profits again, and analysts pronounced that the slide had been halted and Apple was a good investment once more.

Jobs was remaking Apple into a company that had at least a chance of surviving in a market hemmed in by consolidation and cloning, heavily commoditized, being reshaped by cyberspace, and dominated by Microsoft and Windows.

Getting Really Personal

Today the computer is not a bag of parts being shipped to us; it is integrated into our telephone and automobile and refrigerator and we don’t need to think about the software because it has become so intuitive and embedded in the product that all we have is life itself.

—Paul Terrell

If the war for control of the PC industry was over, Apple’s hope, Jobs believed, was to stay alive long enough to be a player in the next big movement.

Some significant change was coming, it was clear; but guessing just what its form would be was the challenge. What happened was that the core of the computing universe began to move away from the desktop and onto mobile devices and the Internet. In the first of these shifts, Jobs and Apple played well and delivered a series of category-defining products. It was one of the most remarkable recoveries in corporate history, and was to be one of the most impressive instances of market domination. Starting in 2001, Apple began to set the mark that the rest of the industry had to hit in one new device category after another.

But as the 1990s came to a close, the world of mobile devices was looking very different.

Windows was not just the operating system of the great majority of personal computers. It was also behind the scenes in everything from point-of-sale terminals and automobiles to early smartphones.

These phones, which came on the scene at the end of the 1990s, were a niche product, the top end of the cell-phone market. They featured extra capabilities like a camera, media player, GPS, and to-do lists and other personal-productivity tools. BlackBerry smartphones from RIM set the bar with email, messaging, and web browsing, and they were the phone of choice for government workers. These phones weren’t full-fledged computers, but they delivered some of the same functionality.

Another popular device category was the digital music player, almost always called an MP3 player (after the widely popular digital music format). There were already analog cassette players, the category-defining example being Nobutoshi Kihara’s Sony Walkman. But British inventor Kane Kramer came up with a design for a digital audio player, along with the means to download music, plus digital-rights-management (DRM) technology, clear back in 1979. He lost the rights to his inventions when he couldn’t afford to renew patents, but his ideas were not lost. By late 1997 the first production-volume commercial digital music player from Audible.com went on sale. Through the end of the millennium the MP3 player market blossomed with many new players, including the Diamond Rio and the Compaq HanGo Personal Jukebox.

The recording industry was terrified. Its trade association, the Recording Industry Association of America (RIAA), regarded these devices as tools for music piracy. The RIAA sued Rio but lost. Although Rio prevailed, other companies didn’t fare as well in the clash between the music industry and Internet culture. Napster was a peer-to-peer file-sharing service primarily used for sharing music MP3s. Founded by Shawn Fanning, John Fanning, and Sean Parker, it prospered from June 1999 to July 2001, peaking at 80 million registered users. Then Metallica and Dr. Dre and several record labels sued, and Napster was shut down by court order.

Napster doubtless hurt some musicians, but it was arguably instrumental in making others, such as Radiohead and Dispatch. These new services and devices challenged traditional thinking in many ways, and they were creating new market niches. Again, the devices were not computers—but they had microprocessors in them and, like the BlackBerry, they could do some of what a computer could do.

The idea of such smart devices predates personal computers. As semiconductor designers had understood back in the 1970s, the chips were the computers. All the other bulky stuff was just there to communicate with humans. For many applications, the level of human interaction expected was relatively minimal. If it didn’t have to do all that a computer did, a device could deliver a lot of capability in a very small package. And significant new markets were finally developing around certain kinds of devices.

Apple was not a player in any of these markets. But in the MP3 devices, Jobs saw an opportunity.

The Player

Technologically, music players were a solved problem. And the market for them was well established. The problem was, it wasn’t exactly a legal market. Jobs had sung the virtues of being a pirate, but getting shut down for music piracy wasn’t what he had in mind.

But Jobs had clout now. As the CEO of Pixar, he was a player in the entertainment industry. Under contract to Disney, Pixar had released Toy Story in 1995 and had gone public the same year. Jobs became an instant billionaire and someone to pay attention to in Hollywood. But it remained to be seen whether his newly minted Hollywood cred would buy him any time with music-industry executives.

And he needed face time with those executives for what he had in mind. There were several pieces to the plan: a music player, a new model for selling music, and buy-in from the music industry.

Somehow, he got it. Somehow he convinced the big players in the industry to license music to Apple under terms never before considered.

But first came the device. The original iPod introduced a scroll wheel as its primary input device, and it had a monochrome LCD display and earbuds. It was marketed with the slogan “1,000 songs in your pocket.” It was basically Kane Kramer’s (now public domain) digital player.

For the selling model, Apple purchased Bill Kinkaid’s SoundJam MP from Casady & Greene in 2000, renamed it iTunes, and released it in 2001. By 2003 iTunes had developed into the first fully legitimate digital music store. DRM software within the store protected the industry from piracy, and a radical pricing model made piracy elsewhere far less appealing. The pricing model made music sales a meritocracy, leveled the playing fields for indies, and destroyed the album. Everything would now be a single, Jobs dictated, and the new price for every song was the same: 99 cents.

The streamlined processing of the iTunes store meant that labels and artists got paid faster than in the past. Much of technology was inherent in Napster and the MP3 format, but Apple put it all together. In the first week the store was open, it sold a million song files.

Sales for the iPod took off more slowly, but by the end of 2004 Apple and its iPod owned some two-thirds of the growing market for digital music players. Margins were big and the profits huge. By 2007 iPod sales were making up roughly half of Apple’s revenue. Apple had, as Jobs knew it must, identified an emerging market and dominated it.

But Apple was not resting on its laurels.

The Phone

As far back as 1983 Jobs knew what he wanted the next product after the desktop or portable personal computer to be. At an offsite meeting for the Mac team, the one where he told them that “real artists ship” and “it’s more fun to be a pirate than to join the Navy,” he also challenged the Mac team to do a “Mac in a book by 1985.”

In a book? Apple would later produce portables called MacBooks, but Jobs wasn’t talking about a portable computer. What he was really talking about was Alan Kay’s Dynabook.

Kay, a Xerox PARC legend, had conceived of the Dynabook years earlier. It was in effect the prototype for every tablet device since created. It was a thin, flat display. Viewing it, you felt like you were reading from a piece of paper rather than a screen. It had no physical keyboard. It was a ubiquitous information and communication device that wasn’t necessarily a computer.

Jobs wanted the Mac team to wrap up the Macintosh quickly and get started on this next big (or little, really) thing, this tablet. But it didn’t happen then or in all the time he was gone, really. In the early 2000s, on the heels of iTunes and the iPod, he was ready to make it Apple’s next product.

It didn’t play out that way, though.

At the January 2007 Macworld show, Jobs announced “three revolutionary products…a wide-screen iPod with touch controls…a revolutionary mobile phone…[and] a breakthrough Internet communications device.” After getting cheers for each of these “devices,” he confided that they were all one product: the iPhone. The iPhone was essentially the tablet device shrunk to handheld size and with a phone packed into it.

It wasn’t the Dynabook, but neither was it a traditional smartphone. One of the things that set it apart from smartphones was the groundbreaking user interface. Another was that it ran Apple’s OS X, a full computer operating system. That didn’t make it a full computer, but it was impressive for the capability it promised.

Jean-Louis Gassée understood how impressive and powerful that was. “I thought Steve was lying. He was saying that OS X was inside the phone. I thought, He’s going to get caught. This time, he’s going to get caught. Well, no. When the geeks had their way with the first iPhones and looked at it…it was genuinely OS X.”

To really make use of a computer operating system in a phone, you had to figure out how to let the user do most of what could be done with a keyboard and a mouse on a device that had neither. The user-interface team, led by Greg Christie, had to invent a whole language of finger gestures. From there, the potential of the device was far beyond what had ever been delivered in a phone.

At the time of the demo, much of that was still potential. The iPhone was nowhere near ready to release when Jobs demoed it. But when it was released a few months later, somewhere around half a million iPhones were sold in the first weekend.

But Apple wasn’t alone in the new market for extra-smart phones. Microsoft had been probing this market with its Windows CE and later its Pocket PC platforms for over a decade. And back in 2003, four entrepreneurs—Andy Rubin, Rich Miner, Nick Sears, and Chris White—started a company named Android to create a new operating system based on the Linux kernel and emphasizing a touch-based interface for tablets, smartphones, and the like. Two years later, the company was acquired by Google, which had been investing its huge income from its search business in various enterprises. The Android project remained in stealth mode, with no hint of any intent to produce a new operating system to compete with Windows Mobile and Symbian—which were the players to beat.

When Apple released the iPhone, the developers recognized that Windows Mobile and Symbian were not the target; Apple’s iOS mobile operating system was. They regeared and, within months, unveiled Android. But arguably more interesting than the technology was the fact that Google announced Android as the first product of a consortium of companies committed to developing open standards for mobile devices. Apple’s iOS was Apple’s own proprietary platform. Two different models for mobile devices were now in competition: the open Android model and the closed iOS model.

Delivering the Tablets

Jobs hadn’t forgotten the Mac-in-a-book dream, though. And he wasn’t alone. Technology companies had been exploring the Dynabook concept for 20 years, since well before Jobs said anything to the Mac team about a Mac in a book. The concept required several innovations: flat-panel displays, the display as input device, and advances to get the machines small enough to carry.

Back in January 1979, inspired by the Dynabook, Xerox PARC researcher John Ellenby left to start a company with friends Glenn Edens, Dave Paulsen, and Bill Moggridge. Working without publicity, they delivered a computer, the GRiD Compass, in 1981—the same year IBM introduced its PC. It was an impressive machine, the first laptop computer, the first with the later ubiquitous foldable “clamshell” design, featuring a novel bit-mapped flat-panel display and a rugged magnesium case. It was a product driven by technological challenge, not budget constraints, and it was priced at $9,000. Fortune magazine named it a product of the year and it found a ready market in the military. It was reputed to be the first piece of consumer equipment (except for the powdered drink Tang) used on the space shuttle.

Although the GRiD Compass inspired an entire industry of laptop computers and its magnesium case was an idea that Steve Jobs picked up on at NeXT, the GRiD machine was no Dynabook. In particular, it used a keyboard for input. But if you could use the screen for input as well as output, you could immediately eliminate half the bulk of the device. A number of companies moved the idea forward over the years.

But while these companies pushed the technology for Dynabook-like devices, many of them were designed to be computers. Part of the genius of the Dynabook, though, was that it didn’t necessarily aspire to that. It was something new—something that didn’t yet exist.

Jerry Kaplan (Symantec Q&A and Lotus Agenda developer), Robert Carr (Ashton-Tate Framework developer), and Kevin Doren (music synthesizers) started Go Corp in 1987 to build on the flat-screen idea by producing a portable computer that used a stylus for input. Their product, the EO Personal Communicator, didn’t take the world by storm, but it did solve a lot of technical problems, and to those in the industry it was at least a proof of concept.

Another personal-computer pioneer who believed in the possibility of these no-keyboard devices was VisiCalc designer Dan Bricklin. In 1990 he and some colleagues founded Slate Corporation with a mission of developing software for pen-based computers.

Then Jeff Hawkins, who had worked at GRiD, started Palm Computing in 1992 to develop handheld devices that were not necessarily computers. He and his team had varying degrees of success with personal digital assistants, smartphones, handwriting-recognition software called Graffiti, and a mobile operating system called WebOS.

Apple, under the leadership of John Sculley, embraced the idea and fielded a whole line of pen-based products under the Newton label. Newton was a handheld computer with its own operating system and some groundbreaking technology. After bad publicity for its iffy handwriting recognition, Apple replaced it with a highly regarded handwriting-recognition system developed in-house by Apple researcher Larry Yaeger and others.

As a demonstration of the achievements of Apple research and development it was wonderful, but it fell somewhat short as a successful consumer product. Consumers were not clamoring to enter data via handwriting. Neither Newton nor any of the other tablet devices from the 1990s succeeded. It would be a decade before the tablet market would truly catch fire.

When Apple finally returned to the tablet market in 2010, its iPad was another category-defining product, like the iPod and iPhone. Skeptics pointed out that it did less than a personal computer, and questioned what the market was for such a device. But that was the point. It was something else, and if it found a market it would be plowing fresh soil. Jobs would again have succeeded in opening a new market.

And the market was there. By mid-2010 Apple had sold a million iPads, and a year later the total was 25 million. The tablet market was booming for other companies as well. Amazon had released a handheld reader called the Kindle in 2007, and it staked out a somewhat different market, being specifically a book-reading device. Google’s mobile operating system, Android, was in use in phones and tablets from many companies, and the Android slice of the tablet market soon surpassed Apple’s. With Android, developers saw the re-emergence of an open platform.

The idea of browser as operating system came to fruition when Google released its Chrome OS in 2009. Built on top of a Linux kernel, its user interface was initially little more than the Google Chrome web browser. Chrome OS was the commercial version of an open source project, Chromium, which opened the source code for others to build on. Laptop computers were soon being built to run Chrome OS natively.

Although Apple was setting the bar in each of these new product categories and profiting greatly from them, it wasn’t necessarily leading in sales. By 2011 Android devices were outselling all others. By 2013 they were outselling all other mobile devices and personal computers combined. Nearly three-quarters of mobile developers were developing for Android. Google’s open model had been a highly successful play.

Meanwhile, sales for personal computers were flat or declining. The center of the computing universe had shifted to these new mobile devices. To be sure, the market for some of these mobile devices may already have been reaching saturation by 2014, as evidenced by a general decline in iPod sales and the hint of a decline in iPad sales. But the trend toward new specialized devices was not dependent on any particular device. New ones were being planned and launched. The personal computer was being deconstructed, its capabilities allocated to more specialized products.

The other major trend away from the desktop wasn’t about physical products, though, and it wasn’t led by Apple.

Into the Cloud

I was always clear, from like 1970, that networked computers were going to be necessary for sustainability of communities. So, then it was a matter of figuring out how to implement that. And it’s not like I suddenly woke up and said, Oh, this is important stuff. No, it was always important stuff for me.

—Lee Felsenstein

By 2000 the Internet was an integral part of life for millions of people. Indeed, 350 million or more people were online, the majority of them in the United States. That figure would grow by an order of magnitude over the next decade and a half, and more closely match the relative populations of countries. By 2014, China was home to the most Internet users.

Robert Metcalfe’s 1995 prediction that the web browser would become the operating system for the next era had largely come true. If, as Sun Microsystems had famously claimed, the network was the computer, then the browser was the operating system, and single-computer-based operating systems were irrelevant. It wasn’t quite that simple, but websites were becoming more like applications, powered by JavaScript. But even if the network was (sort of) the computer, that didn’t mean the actual computer could be turned into a glorified terminal, as Larry Ellison had discovered back in 1996 (when Oracle and Netscape were unsuccessful with what they called a network computer, or NC). A new model of computing was emerging, but the NC model wasn’t it.

In the 21st century, that new model revealed itself in the ubiquity of e-commerce and social media, and it grew on top of new algorithms and technologies designed to process data in new ways. Beneath all that was the data—data being collected and stored and processed on a scale far beyond anything human beings had ever experienced.

E-commerce as presently known didn’t happen until 1991, when the National Science Foundation lifted its restrictions on commercial use of the Internet. But with the launch of Amazon and eBay in 1995 and PayPal in 1998, online shopping was soon threatening the viability of brick-and-mortar stores.

The easiest product to sell online was software. Gone were the shrink-wrapped boxes on shelves in computer stores. And with the dominance of portable devices, the programs got smaller. Even the name got smaller: the biggest category of computer software used to be called application software, but now it was just apps. The average price dropped even more, from tens, hundreds, or even thousands of dollars to a couple of bucks.

What made it possible to write and sell two-dollar apps was the shift of processing to the Internet. Mobile apps often functioned simply as interfaces to web-based applications. And in that online market there were huge opportunities, with venture capitalists throwing money at every new instance of Gates’s bright young hacker. And while e-commerce was booming, the biggest opportunity to make your first billion was in the emerging market of social media.

Since the earliest days of personal computing, the online element of it had been at least in part about community. This online community, which Ted Nelson had called “the future intellectual home of mankind” in Computer Lib, Lee Felsenstein was working to build through projects like Community Memory. Later, online systems such as CompuServe and AOL succeeded because they provided that sense of a community. With its eWorld, Apple went so far as to build an online service around a cartoon town.

The World Wide Web put an end to these isolated services and opened up the world, but it was not a single community. New web-based services emerged, like MySpace and Friendster, each acutely aware of the huge opportunity there was for those who could successfully create that sense of community.

The most successful of these was Facebook, started by a bright young hacker at Harvard in 2004. Within ten years its community would have more members than there were people on the Internet in 2000.

A spate of new companies started by recent grads with major backing were all defining themselves against Facebook, with many of them successfully identifying communities of professionals, photographers, videographers, and devotees of various crafts. These overnight successes did not produce products in the sense that the iPod was a product. But just as Apple succeeded by designing products that people would want, these social-media companies succeeded by understanding key facts about how people connected. Their sites were highly personal.

The booming e-commerce and social-media sites had a serious problem, though: they made demands on storage and processing that existing hardware and software couldn’t deliver. In 2014 Amazon required some half a million servers to process its orders. Facebook had about half that many. The services had grown far beyond the point where a single computer of any size could do the job. But connecting any two individuals in a massive network or keeping inventory current across so many orders required new tools. The established ones simply did not scale. The work had to be distributed. New programming tools came on board, better suited to the parallelization of work to allocate it among many widely distributed processors.

Big as Facebook and Amazon were, their needs were dwarfed by those of the biggest dot-com company. This was neither an e-commerce site nor a social-media site; it was a search engine. The Web was huge, and just searching it was an even bigger job than the task facing an Amazon or a Facebook. Many search engines had been developed, but one was dominant in the 21st century: Google. Its processing and storage needs were massive, requiring huge warehouses with hundreds of thousands of servers at each one of these “server farms.”

A new term began to gain popularity: cloud computing. It was an old idea, but the technology to make it work was now in place. The distributed computing technology worked. It scaled. And soon you didn’t have to be an Amazon or a Facebook or a Google to benefit from these innovations. Google, HP, IBM, and Amazon turned this in-house technology into a marketable service. They made it possible for any business to distribute processing and storage with maximum efficiency. Amazon Web Services, or AWS, began renting Amazon’s distributed computing capability. You could rent computers, storage, the processing power of computers—virtually any definable capability of computers—on an as-needed basis. If your business grew rapidly and you needed ten times the capability tomorrow as today, you just bought more.

By 2014, seven out of eight new applications were being written for the cloud.

Meanwhile, the increases in computers’ storage capacity were continuing to redefine what computer technology was capable of. “Big data” is the term applied to the new collections of data emerging from the data-gathering of search engines—from online transactions with humans and from Internet-connected sensors gathering data like temperatures—collections so large that no traditional database tool could process them.

Computing had changed. People were now interacting with a growing variety of devices, only a fraction of which were personal computers as traditionally understood—devices that more often than not simply mediated interaction with an e-commerce or social-media site elsewhere, which in turn stored its data and executed its code in a virtual cloud, the physical location of which was not only shifting and hard to pin down but, in practice, unimportant. The model of a personal computer on your desk or lap had become quaint. The personal-computer era was giving way to something else: a post-PC era.

Paralleling this shift away from the personal computer has been a general changing of the guard among the players.

Leaving the Stage

In 2011, at the age of 56, Steve Jobs died due to complications from pancreatic cancer. A few months earlier he had stepped down as CEO, telling the board, “I have always said if there ever came a day when I could no longer meet my duties and expectations as Apple’s CEO, I would be the first to let you know. Unfortunately, that day has come.” COO Tim Cook was named CEO.

In 2013, Steve Ballmer retired as CEO of Microsoft. The company had been struggling to find its way in recent years, failing to secure a significant market share in the new product categories. Satya Nadella, a 22-year Microsoft veteran, would become only the third CEO in Microsoft’s history. Tellingly, Microsoft turned to cloud computing to lead it into the future.

In 2014, Oracle’s Larry Ellison stepped down as CEO of the company he founded. Many of the companies that had helped to define the personal-computer era were gone now, including Sun Microsystems, which Oracle acquired. In Silicon Valley there was a pervading sense that the old guard was gone and that the industry was in the hands of a freshman class of bright young hackers. And in terms of products, those bright young hackers were driving the vehicle of technology to a new era.

In this new era, handheld devices have become wearable, and are moving past wearable to embedded. We’re in that era now. From a device that you can put down when you’re done with it to a device that you take off like jewelry to a device that would require outpatient surgery to disconnect, smart devices are going beyond the personal, to the intra-personal. At the same time, these devices are deeply entwined with the Internet, talking to other devices in a new “Internet of things,” bypassing their slow fleshy hosts.

The two trends of smaller and more intimate devices and of an increasingly ubiquitous network are coming together to produce something that transcends either individual technology. The results will be interesting.

Looking Back

It’s a brave new world we are embarking on with all of our embedded personal computers that have been programmed by others who hopefully have our well being in mind.

—Paul Terrell

What is a personal computer?

To those who first built them, a personal computer meant a computer of your own. It meant a lot. That was the promise of the microprocessor: that you could have a computer of your own.

And that, to some—the time in question being the tail end of the idealistic ’60s—implied empowering others as well. "Computer power to the people" was not just a slogan heard in those days; it was a motivating force for many personal-computer pioneers. They wanted to build computers to be used for the betterment of mankind. They wanted to bring the power of computers to everyone.

This humanitarian motive existed alongside other, more self-centered motives. Having your own computer meant having control over the device, with the sense of power that brought. If you were an engineer, if you were a programmer, it specifically meant control over this necessary tool of your trade.

But control over the box was just the start; what you really needed was control over the software. Software is the ultimate example of building on the shoulders of others. Every program written was either pointlessly reinventing the wheel or building on existing software. And nothing was more natural than to build on other programs. A program was an intellectual product. When you saw it and understood it, you had it; it was a part of you. It was madness to suggest that you couldn’t use knowledge in your own head—and only slightly less mad to try to prevent you from acquiring knowledge that would help you do your job.

The idea of owning your own computer, paradoxically, fed the idea of not owning software, the idea that software should be open to be observed and analyzed, independently tested, borrowed, and built on. It supported the ideas of open source software and nonproprietary architectures, a collaborative perspective that John “Captain Crunch” Draper had called “the Woz principle” (for Steve Wozniak).

How have these ideas—the Woz principle and computer power for the people—fared with the deconstruction of the personal computer?

The Woz Principle

There was once an ongoing debate about the merits of proprietary versus open source software. Supporters of open source argued that it was better than the commercial kind because everyone was invited to find and fix bugs. They claimed that in an open source world, a kind of natural selection would ensure that only the best software survived. Eric S. Raymond, an author and open source proponent, contended that in open source we were seeing the emergence of a new nonmarket economy, with similarities to medieval guilds.

The debate is effectively over. Open source software didn’t drive out proprietary software, but neither is open source going away. This open source idea, what John Draper had called the Woz principle, is really just an elaboration of the sharing of ideas that many of the pioneers of the industry had enjoyed in college, and that scientifically trained people understood was the key to scientific advance. It was older than Netscape, older than Apple, older than the personal-computer revolution. As an approach to developing software, it began with the first computers in the 1940s and has been part of the advance of computer-software technology ever since. It was important in the spread of the personal-computer revolution, and now it powers the Internet.

The market for post-PC devices is different from the market for personal computers. The personal computer started as a hobbyist product designed by tech enthusiasts for people like themselves. Commoditization began in just a few years, but the unique nature of the computer—a device whose purpose is left to the user to define—allowed it to resist commoditization for decades. In the post-PC era, even though the devices are still really computers they are designed around specific functions. So the forces of commoditization that had been held at bay are now rushing in. The mainstream market for these devices doesn’t want flexibility and moddability and choices to make once they’ve purchased a device. They want it all to be simple, clear, consistent, and attractive. They don’t care about open source, but they like free. They want security but they don’t want to have to do anything about it. Their values are not the values of the people making the devices or the apps. They’re normal consumers, something the companies in the early personal-computer industry never really had to acknowledge.

If you look only at commercial apps, you will conclude that proprietary software, locked-down distribution channels, and closed architectures have won. If you look at the Internet and the Web and at the underlying code and practices of web developers, on the other hand, it is clear that open source and open architecture and standards are deeply entrenched.

And even in the device space, the differing models of Android and Apple suggest that things may shift further in the direction of the Woz principle. In this revolution, the workers have often succeeded in controlling the tools of their trade.

The implications go beyond the interests of software developers. Google’s Android model has allowed the development of lower-priced platforms that benefit the developing world, where personal computers and iPhones are out of the price range of many people.

As for the developers, a change has occurred in the makeup of that community. Hobbyists, who comprised the bulk of early personal-computer purchasers and developers, are harder to find in the post-PC era. When new phones and tablets hit the market now, they don’t come with BASIC installed, as the Apple II did. The exceptions are in programmable microcomputers used to program devices. The low-budget Arduino and Raspberry Pi being used by electronics hobbyists of today are rare examples of computers that are still intended to be programmed by their users. Perhaps the shift away from hobbyist programming is balanced by the growth in website development, which has a very low barrier to entry.

The industry has changed, but for one player the change had come much earlier, and he decided he didn’t want to be a part of it any longer.

The Electronic Frontier

At the height of his power and influence at Lotus Development Corporation, Mitch Kapor walked away from it all.

Lotus had grown large very quickly. The first venture capital arrived in 1982, Lotus 1-2-3 shipped in January 1983, and that year the company made $53 million in sales. By early 1986 some 1,300 people were working for Lotus. Working for Mitch Kapor.

The growth was out of control, and it was overwhelming. Rather than feeling empowered by success, Kapor felt trapped by it. It occurred to him that he didn’t really like big companies, even when he was the boss.

Then came a day when a major customer complained that Lotus was making changes in its software too often: that it was, in effect, innovating too rapidly. So what was Lotus supposed to do, slow down the pace of innovation? Exactly. That’s what the company did. It was perfectly logical. Kapor didn’t really fault it as a business decision. But what satisfaction was there in dumbing down your company?

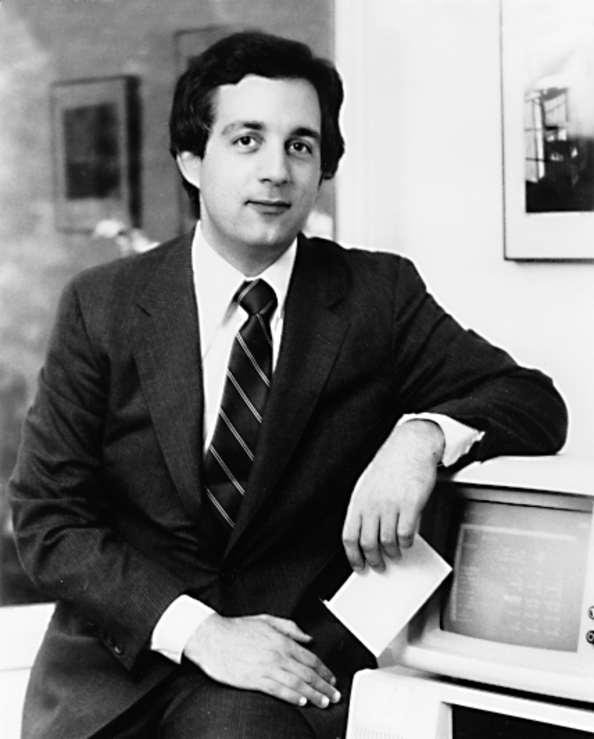

Figure 94. Mitch Kapor Kapor went from teaching transcendental meditation to founding one of the most successful companies in personal computing’s boom days to defending individual rights in the information age.

(Courtesy of Mitch Kapor)

Lotus just wasn’t fun anymore. So Kapor resigned. He walked out the door and never looked back.

This act left him with a question: what now? After having helped launch a revolution, what should he do with the rest of his life? He didn’t get away from Lotus cleanly. He had spent a year completing work on a Lotus product called Agenda while serving as a visiting scientist at MIT. After that he jumped back in and started another firm, the significantly smaller On Technology, a company focusing on software for workgroups.

And in 1989 he began to log on to an online service called The Well. The Well, which stood for Whole Earth ’Lectronic Link, was the brainchild of Stewart Brand, who had also been behind The Whole Earth Catalog. The Well was an online community of bright, techno-savvy people.

“I fell in love with it,” Kapor said later, because “I met a bunch of people online with similar interests who were smart that I wanted to talk to.” He plunged headlong into this virtual community.

One day in the summer of 1990, he even found himself on a cattle ranch in Wyoming talking computers with John Perry Barlow, a former lyricist of the Grateful Dead.

What led to that unlikely meeting was a series of events that bode ill for civil liberties in the new wired world. A few months earlier, some anonymous individual, for whatever motive, had “liberated” a piece of the proprietary, secret operating-system code for the Apple Macintosh and had mailed it on floppy disks to influential people in the computer industry. Kapor was one of these people; John Perry Barlow—the former Grateful Dead lyricist, current cattle rancher, and computer gadfly—was not. But apparently because Barlow had attended something called The Hacker’s Conference, the FBI concluded that Barlow might know the perpetrator.

The Hacker’s Conference was a gathering of gifted programmers, industry pioneers, and legends, organized by the same Stewart Brand who had launched The Well. Hacker in this context was a term of praise, but in society at large it was coming to mean “cybercriminal”—that is, one who illegally breaks into others’ computer systems.

An exceptionally clueless G-man showed up at Barlow’s ranch. The agent demonstrated his ignorance of computers and software, and Barlow attempted to educate him. Their conversation became the subject of an entertaining online essay by Barlow that appeared on The Well.

Soon afterward, Barlow got another visitor at the ranch. But this one, being the founder of Lotus Development Corporation, knew a lot about computers and software. Kapor had received the fateful disk, had had a similar experience with a couple of clueless FBI agents, had read Barlow’s essay, and now wanted to brainstorm with him about the situation.

“The situation” transcended one ignorant FBI investigator or a piece of purloined Apple software. The Secret Service, in what they called “Operation Sun Devil,” had been waging a campaign against computer crime, chiefly by storming into the homes of teenaged computer users at night, waving guns, frightening the families, and confiscating anything that looked like it had to do with computers.

“The situation” involved various levels of law enforcement responding, often with grotesquely excessive force, to acts they scarcely understood. It involved young pranksters being hauled into court on very serious charges in an area where the law was murky and the judges were as uninformed as the police.

It did not escape the notice of Barlow and Kapor that they were planning to take on the government, to take on guys with guns.

What should they do? At the very least, they decided, these kids needed competent legal defense. They decided to put together an organization to provide it. As Kapor explained it, “There was uninformed and panicky government response, treating situations like they were threats to national security. They were in the process of trying to put some of these kids away for a long time and throw away the key, and it just felt like there were injustices being done out of sheer lack of understanding. I felt a moral outrage. Barlow and I felt something had to be done.”

In 1990 they cofounded the Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF). They put out the word to a few high-profile computer-industry figures who they thought would understand what they were up to. Steve Wozniak kicked in a six-figure contribution immediately, as did Internet pioneer John Gilmore.

Merely fighting the defensive battles in the courts was a passive strategy. EFF, they decided, should play an active role. It should take on proposed and existing legislation, guard civil liberties in cyberspace, help open this new online realm to more people, and try to narrow the gulf between the “info haves” and the “info have-nots.”

The pace picked up when they hired Mike Godwin to head their legal efforts. “Godwin was online a lot as he was finishing law school at the University of Texas,” Kapor remembers. “I was impressed by him.”

EFF evolved quickly from a legal defense fund for some kid hackers to an influential lobbying organization. “In a way it was an ACLU of cyberspace,” Kapor now says. “We quickly found that we were doing a lot of good raising issues, raising consciousness [about] the whole idea of how the Bill of Rights ought to apply to cyberspace and online activity. I got very passionate about it.”

By 1993, EFF had an office in Washington and the ear of the Clinton administration, especially Vice President Al Gore, who dreamed of an information superhighway analogous to his father’s (Senator Albert Gore, Sr.) favorite project, the interstate highway system. Also addressing the issues were organizations such as Computer Professionals for Social Responsibility, which EFF was partly funding.

To a personal-computer pioneer intent on using the power of computers to benefit people and exorcising the shibboleth of the computer as an impersonal tool of power over the masses, this looked promising. It looked like dumb, slow, old power structures on one side and clever, agile, new techno-savvy revolutionaries on the other.

And since those heady days? It is easy to conclude that the problems EFF was created to address are growing faster than the efforts of such organizations can handle. Revelations that the US government is, with the help of huge cloud corporations, tapping into the massive stores of data they collect on citizens of the United States, on foreign countries, and on foreign heads of state, have undermined confidence not just in government but in technology. Once again, as before the personal-computer revolution, computer technology is starting to be seen as power that can be used by the powerful against regular people.

Ironically, the social networks built by the cloud-based companies have become the means of circulating both facts and wild rumors about these surveillance horrors. As the industry rushes gleefully into a networked world of embedded devices and lives lived in public, the public is increasingly convinced that we are being sucked into some nightmare science-fiction future of mind control, tracking devices embedded in newborns, and a Big Brother who sees your every act and knows your every thought. Mary Shelley could do a lot with that material.

But the fears are not groundless. Computers actually have given great power to individuals, and they will continue to do so. But this question cannot be avoided: can we keep them from taking away our privacy, our autonomy, and our freedom?

Looking Forward

The revolution that produced the personal computer is over. It grew out of a unique mixture of technological developments and cultural forces and burst forth with the announcement of the Altair computer in 1975. It reached critical mass in 1984, with the release of the Apple Macintosh, the first computer truly designed for nontechnical people and delivered to a broad consumer market. By the 2000s the revolutionaries had seized the palace.

The technology carried in on this revolutionary movement is now the driving force of the economies of most developed countries and is contributing to the development of the rest. It has changed the world.

Changing the world. By 1975, time and again crazy dreamers had run up against resistance from accepted wisdom and had prevailed to realize their dreams. David Ahl trying to convince Digital Equipment Corporation management that people would actually use computers in the home; Lee Felsenstein working in post-1965 Berkeley to turn technology to populist ends; Ed Roberts looking for a loan to keep MITS afloat so it could build kit computers; Bill Gates dropping out of Harvard to get a piece of the dream; Steve Dompier flying to Albuquerque to check up on his Altair order; Dick Heiser and Paul Terrell opening stores to sell a product for which their friends told them there was no market; Mike Markkula backing two kids in a garage—dreamers all. And then there was Ted Nelson, the ultimate crazy dreamer, envisioning a new world and spending a lifetime trying to bring it to life. In one way or another, they were all dreaming of one thing: the personal computer, the packaging of the awesome power of computer technology into a little box that anyone could own.

Changing the world. It’s happening all the time.

Today that little box is taken for granted at best, and just as often supplanted by new devices, services, and ideas that will, in turn, be supplanted by newer, possibly better ones. Technological innovation on a scale never seen in human history is simply a fact of life today.

Perhaps the lesson of the personal-computer revolution is that technological innovations are never value-neutral. They are motivated by human hopes and desires, and they reflect the values of those who create them and of those who embrace them. Perhaps they are a reflection of who and what we are. If so, are we happy with what they show us?

In any case, we seem to be in an era of unbridled technological innovation. You can’t guess what new technological idea will shake the world, but you can be sure it is coming. Some bright young hacker is probably working on it today.

She may even be reading this book right now.