Total Information Risk Management (2014)

PART 3 Total Information Risk Management Techniques

CHAPTER 13 Establishing Organizational Support and Employee Engagement for TIRM

Abstract

This chapter discusses strategies and concepts to overcome organizational resistance and increase employees’ support for TIRM.

Keywords

Overcoming Organizational Resistance for Information Risk Management; Establishing Employee Support for Information Risk Management; Organizational Culture; Change Management

What you will learn in this chapter

![]() How to overcome organizational resistance during TIRM implementation

How to overcome organizational resistance during TIRM implementation

![]() The reasons for organizational resistance

The reasons for organizational resistance

![]() How to change organizational culture

How to change organizational culture

![]() How to engage employees in information risk management

How to engage employees in information risk management

Introduction

TIRM is multidisciplinary and it should involve everyone in the organization rather than be the responsibility of a few key individuals. Not everyone will love your TIRM initiative from day one. There will be some people in every organization who feel threatened by the rising role of data and information assets and might do everything to stop you from succeeding. By involving people from the outset and making them feel that their contributions are valued, engagement and buy-in to the (new) processes will be easier to achieve. This chapter reviews techniques for managing change, how to overcome resistance, and how to engage employees to ensure the successful management of information risks.

Establish organizational support and changing organizational culture

Implementing a TIRM program within an organization will require changes that without doubt will create organizational resistance. Resistance to change is not uncommon, and those responsible for the implementation of change programs and procedures may have to work hard to overcome that resistance.

STRATEGIES FOR OVERCOMING ORGANIZATIONAL RESISTANCE

One model for reducing resistance to change is offered by Kotter and Schlesinger (1979). It has been well documented in the literature and has stood the test of time. They consider that people (employees) resist change for the following main reasons:

![]() Parochial self-interest—some people are concerned with the implication of the change for themselves. They think they will lose something of value as a result. People focus on their own best interests rather than considering the effects for the success of the business.

Parochial self-interest—some people are concerned with the implication of the change for themselves. They think they will lose something of value as a result. People focus on their own best interests rather than considering the effects for the success of the business.

![]() Misunderstanding and lack of trust—people resist change when they do not understand its implications. They perceive that they have more to lose rather than gain from the change. This often occurs when trust is lacking between those implementing change and the employees.

Misunderstanding and lack of trust—people resist change when they do not understand its implications. They perceive that they have more to lose rather than gain from the change. This often occurs when trust is lacking between those implementing change and the employees.

![]() Different assessments of the situation—employees assess the situation differently from the initiators of change. Initiators (i.e., change managers) assume that employees have all the relevant information, however, they may not, and as a consequence some employees may disagree on the reasons for the change and the advantages of the change process.

Different assessments of the situation—employees assess the situation differently from the initiators of change. Initiators (i.e., change managers) assume that employees have all the relevant information, however, they may not, and as a consequence some employees may disagree on the reasons for the change and the advantages of the change process.

![]() Low tolerance to change—some people are very keen on security and stability in their work and they prefer the status quo—that is, for things to remain as they are. Even when intellectually they understand that change is good, emotionally they are unable to make the transition.

Low tolerance to change—some people are very keen on security and stability in their work and they prefer the status quo—that is, for things to remain as they are. Even when intellectually they understand that change is good, emotionally they are unable to make the transition.

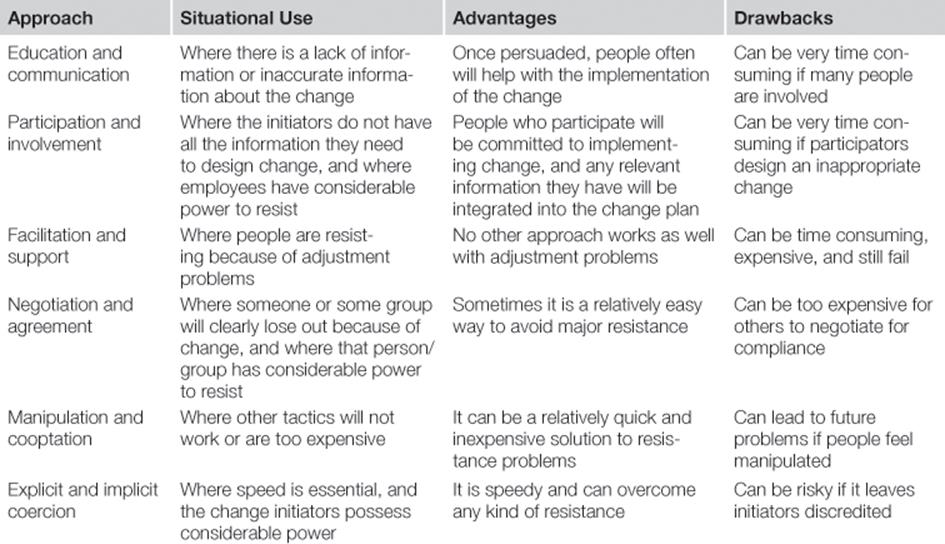

Kotter and Schlesinger set out six approaches to deal with resistance to change shown in Table 13.1.

Table 13.1

Methods of Reducing Resistance to Change

Source: Kotter and Schlesinger, 1979.

Organizational culture is a critical success factor in the roll out of any new initiative and TIRM will only succeed if the culture supports it. Developing the right cultural environment where TIRM could become embedded in organizational processes may be one of the biggest challenges that organizations could face. Establishing the desired organizational culture in which employees do the (right) things expected of them is critical in terms of making the most of your TIRM initiative. Some senior managers do not always appreciate or understand the impact of organizational culture and incorrectly assume that employees will behave in particular ways. Stories about the failure of new initiatives abound, and it is often due to the absence of prioritizing the work that needs to be done to create the right cultural characteristics. Even when an organization publishes its vision, mission, and articulates its values, the right behaviors need to be reinforced if these beliefs and practices are to become reality. This must be done through the development of a culture that underpins such standards and behaviors. Integrating TIRM and ensuring everyone in the organization adheres to the standards expected is only possible by developing and maintaining the right cultural environment.

![]() THEORETICAL EXCURSION: SCHOLARS OF ORGANIZATIONAL CULTURE

THEORETICAL EXCURSION: SCHOLARS OF ORGANIZATIONAL CULTURE

The term culture has its theoretical roots within social anthropology and was first introduced into the English language by Edward B. Tylor in 1871. He defined it as “that complex whole which includes knowledge, beliefs, art, morals, law customs and any other capabilities and habits acquired by man as a member of society” (Tylor, 1871). Since Tylor’s original conception of culture there have been many researchers who have built on his work and redefined his definition. In the late 1970s we began to see organizational culture and management appearing in the mainstream literature on organizational theory. Interest in organizational culture grew in the 1980s as researchers began to explore the factors underpinning Japan’s successful economic performance. Authors like Pascale and Athos (1981), Deal and Kennedy (1982), and Peters and Waterman (1982) moved attention away from national culture to organizational culture and wrote extensively about how organizations that had deeply embedded some shared values were far more successful than those that had not.

Hofstede (1980; Hofstede et al., 1990) and Trompenaars (Trompenaars and Prud’homme, 2009) are two of the leading authorities on managing organizational culture. Hofstede defines culture as ‘mental programming’ and Trompenaars defines it as

the pattern by which a company connects different value orientations (for instance, rules versus exceptions or a people focus versus a focus on goals) in such a way that they work together in a mutually enhancing manner. The corporate culture pattern shapes a shared identity which helps to make corporate life meaningful for the members of the organization and contributes to their intrinsic motivation for doing the company’s work.

Another well-regarded author, Schein (1985) defines culture as

the shared values, beliefs and practices of people in the organization. It is reflected in the visible aspects of the organization, such as its mission statement and espoused values. However, culture exists at a deeper level and is embedded in the way that people act, what they expect of each other, and how they make sense of each other’s actions. Culture is rooted in the organization’s core values and assumptions; often these are not only unarticulated but so taken for granted that they are hard to articulate and invisible to organizational members.

Organizational culture is shaped by a combination of explicit and implicit messages. Johnson (1992) suggests that organizations have a cultural paradigm that defines how they view themselves and their environment. The paradigm evolves over time and shapes strategy: managers draw on frames of reference that have been built up over time and are especially important at a collective organizational level. The notion of the paradigm lies within a cultural web and is represented in Figure 13.1.

FIGURE 13.1 Cultural web.

The cultural web is a tool that enables a cultural audit to be undertaken. By considering the beliefs and assumptions represented by the six outer circles, you can assess the current culture.

So, how can an organization create the right culture, one that supports the wider organizational goals and risk appetite? Does the culture need to change? Changing the culture may not be a matter of discarding the existing culture and implementing a new one, but rather building on what currently supports an initiative like TIRM and fine-tuning those aspects that currently hinder TIRM’s integration into day-to-day practices. An approach for a cultural change program has been proposed by Trompenaars and Prud’homme (see following box).

CORPORATE CULTURE CHANGE PROGRAM

Trompenaars and Prud’homme (2009) state that “the dilemma of change needs to be reconciled by ‘dynamic stability’ or ‘continuity through renewal.’” Despite the pressures for achieving change, it is important to ensure the strengths of current corporate culture do not get lost. A meaningful corporate culture is a mix of existing core values and new, aspirational ones. Therefore, it is necessary to know your existing culture and what you want to retain from it before embarking on a change project. Trompenaars and Prud’homme propose the following schedule for a corporate culture change program:

1. Assess current culture (through questionnaires, document analysis, interviews, focus groups).

2. Create input for future corporate culture and core values (including obtaining commitment from the top).

3. Discuss in organization (involving people at different levels, and working on business and organizational dilemmas).

4. Finalize definition of desired culture and target corporate values (including action plan to support implementation).

5. Implementation (embedding the corporate culture in processes and instruments and working on organizational/behavior change).

6. Monitor (live the corporate culture and learn from day-to-day experiences in the new culture).

Having assessed the current culture, the next step is to envisage what the ideal culture should look like. Define the ideal and ensure those aspects that are required to underpin the TIRM initiative are included. Finalize the ideal state; build a picture of what the future should look like. What are the main cultural characteristics that need to be embedded within the organization? How do you want employees to behave? How do you want them to manage information risk?

![]() Implementation should be led from the top; involve everyone and ensure that there are open lines of communication so that there is clarity about expectations.

Implementation should be led from the top; involve everyone and ensure that there are open lines of communication so that there is clarity about expectations.

![]() Consider using ”culture champions” to promote and embed new ways of working.

Consider using ”culture champions” to promote and embed new ways of working.

![]() Provide training, coaching, and mentoring, and help people abandon the behaviors associated with poor or inadequate risk management processes. Often the greatest challenge in changing behavior is not getting people to behave in new ways but getting them to stop behaving in established ways.

Provide training, coaching, and mentoring, and help people abandon the behaviors associated with poor or inadequate risk management processes. Often the greatest challenge in changing behavior is not getting people to behave in new ways but getting them to stop behaving in established ways.

![]() Consider reward and recognition strategies to incentivize the right behaviors.

Consider reward and recognition strategies to incentivize the right behaviors.

![]() Consider too what penalties or sanctions might be appropriate for behaviors that compromise risk management processes.

Consider too what penalties or sanctions might be appropriate for behaviors that compromise risk management processes.

Do not forget to monitor the progress. Track how effectively the new culture is evolving and how it is facilitating TIRM and take corrective action if required. Changing organizational culture and embedding new ways of working and behaving will take time. It may be difficult and indeed uncomfortable but it can be done.

Employee engagement in tirm

Employee engagement plays a significant role for the success of TIRM. Information is quite rightly seen as the lifeblood of many organizations, and it is vital that all employees see their role as one that encompasses the proper management of information risk. How then does an organization achieve this? How do all employees come to regard information risk management as an integral component of their day-to-day activities?

A report by PriceWaterhouseCoopers (PwC) (2009) suggests that there are four key steps that, if followed, will ensure that risk management (and by definition, information risk management) is part of the daily activities of everyone in the organization. Following these four steps will help improve employee engagement.

The four key steps are:

1. Focus on personal accountability.

2. Hold your business units accountable.

3. Lead from the front.

4. Refocus your risk management function.

Focus on personal accountability

![]() Clarify responsibility, authority, and accountability. Before asking people to do something, make sure you have given them the authority they need to complete the task and make it clear how they will be held accountable. It is not at all unusual to see employees being asked to do something without being given the necessary resources with which to achieve those tasks. Neither is it unusual to see employees failing to understand the repercussions they could face if a task or tasks are not carried out successfully. Clear communication and a full appreciation of one’s role are the keys here.

Clarify responsibility, authority, and accountability. Before asking people to do something, make sure you have given them the authority they need to complete the task and make it clear how they will be held accountable. It is not at all unusual to see employees being asked to do something without being given the necessary resources with which to achieve those tasks. Neither is it unusual to see employees failing to understand the repercussions they could face if a task or tasks are not carried out successfully. Clear communication and a full appreciation of one’s role are the keys here.

![]() Encourage staff to question the allocation of responsibility. Is your organization the type in which employees take responsibility for tasks even though the resources they need are not made available to them? Alternatively, is your organization one where staff shy away from taking responsibility because they are fearful of possible consequences? A free and open dialog is needed in both cases with employees knowing exactly what they are responsible for and the consequences of noncompliance.

Encourage staff to question the allocation of responsibility. Is your organization the type in which employees take responsibility for tasks even though the resources they need are not made available to them? Alternatively, is your organization one where staff shy away from taking responsibility because they are fearful of possible consequences? A free and open dialog is needed in both cases with employees knowing exactly what they are responsible for and the consequences of noncompliance.

![]() Watch out for blind spots. Encourage staff to speak out and challenge the status quo and the identification of any shortcomings in the risk management processes. Establish a “no-blame” culture so that employees are comfortable sharing their failures openly. This helps the organization learn quickly how to manage vulnerabilities and address risk incidents.

Watch out for blind spots. Encourage staff to speak out and challenge the status quo and the identification of any shortcomings in the risk management processes. Establish a “no-blame” culture so that employees are comfortable sharing their failures openly. This helps the organization learn quickly how to manage vulnerabilities and address risk incidents.

![]() Keep the door open. Invite employees to speak out if they suspect that something is wrong. You need employees to be comfortable in speaking up before a situation escalates to a position where it is not recoverable and does lasting damage to the organization.

Keep the door open. Invite employees to speak out if they suspect that something is wrong. You need employees to be comfortable in speaking up before a situation escalates to a position where it is not recoverable and does lasting damage to the organization.

![]() Reward the right behavior. Show that you value employees who behave responsibly and honestly by recognizing the contribution they make. There is a natural reticence to report errors for fear of misconduct proceedings being instigated and/or being seen as an informer. The danger is that when problems go unreported, the same mistakes get made repeatedly and are never addressed nor rectified. Reward employees who manage risks appropriately. It is unhealthy and indeed unwise to believe all risks are detrimental to the organization. The nature of business means that properly calculated risks should be taken, and where these lead to successful outcomes, employees should be rewarded. It may be that an incentive program would help ensure that the right behavior is rewarded.

Reward the right behavior. Show that you value employees who behave responsibly and honestly by recognizing the contribution they make. There is a natural reticence to report errors for fear of misconduct proceedings being instigated and/or being seen as an informer. The danger is that when problems go unreported, the same mistakes get made repeatedly and are never addressed nor rectified. Reward employees who manage risks appropriately. It is unhealthy and indeed unwise to believe all risks are detrimental to the organization. The nature of business means that properly calculated risks should be taken, and where these lead to successful outcomes, employees should be rewarded. It may be that an incentive program would help ensure that the right behavior is rewarded.

Hold your business units accountable

![]() Make your business units measure the maturity of their risk processes. Many organizations do not manage their information risks as well as they should because the underlying risk management processes are not well established (nor understood). Each business unit manager should assess the maturity of their risk management processes, identify any issues and shortcomings, then take steps to address these matters so that the unit (and the organization) is no longer vulnerable to risk/loss.

Make your business units measure the maturity of their risk processes. Many organizations do not manage their information risks as well as they should because the underlying risk management processes are not well established (nor understood). Each business unit manager should assess the maturity of their risk management processes, identify any issues and shortcomings, then take steps to address these matters so that the unit (and the organization) is no longer vulnerable to risk/loss.

![]() Get your managers to sign on the line. Insist that business unit managers sign off on the risks they have assumed. Regular reviews should be undertaken, with action plans devised and implemented to address identified risks. There should be open lines of communication with senior management who should be made aware of any new risks that have been identified.

Get your managers to sign on the line. Insist that business unit managers sign off on the risks they have assumed. Regular reviews should be undertaken, with action plans devised and implemented to address identified risks. There should be open lines of communication with senior management who should be made aware of any new risks that have been identified.

![]() Create robust controls. Each business unit should have controls in place that reflect the organization’s risk appetite, taking into consideration the legal and regulatory frameworks within the industry. Remain alive as well to changes in legislation and regulatory regime.

Create robust controls. Each business unit should have controls in place that reflect the organization’s risk appetite, taking into consideration the legal and regulatory frameworks within the industry. Remain alive as well to changes in legislation and regulatory regime.

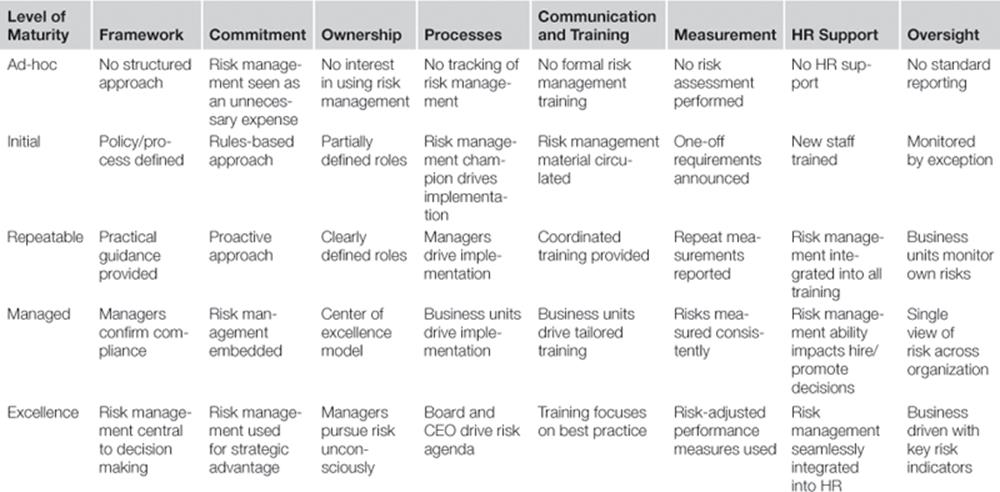

![]() In the report a model for measuring the maturity of an organization’s risk management process is offered as a starting point, shown in Table 13.2.

In the report a model for measuring the maturity of an organization’s risk management process is offered as a starting point, shown in Table 13.2.

Table 13.2

Model for Measuring the Maturity of an Organization’s Risk Management Processes

Lead from the front

![]() Make your presence felt. Show business unit managers that the organization is serious about information risks by reviewing on a regular basis how they address information risks.

Make your presence felt. Show business unit managers that the organization is serious about information risks by reviewing on a regular basis how they address information risks.

![]() Look at the big picture. Ask business unit managers which processes can be simplified or safely eliminated. Many large organizations have grown through mergers and acquisitions; they comprise a complex web of people, business practices, and IT systems that have never been fully integrated. This complexity may be supported by good business reasons, but it also adds to the information risks organizations face.

Look at the big picture. Ask business unit managers which processes can be simplified or safely eliminated. Many large organizations have grown through mergers and acquisitions; they comprise a complex web of people, business practices, and IT systems that have never been fully integrated. This complexity may be supported by good business reasons, but it also adds to the information risks organizations face.

![]() Capitalize on technology. Encourage business units to adopt new tools (e.g., data-mining software, scenario-planning software) to keep track of what is happening. Most business units collect a good deal of information, and such tools can help make better sense of the data and what additional information they need to know.

Capitalize on technology. Encourage business units to adopt new tools (e.g., data-mining software, scenario-planning software) to keep track of what is happening. Most business units collect a good deal of information, and such tools can help make better sense of the data and what additional information they need to know.

![]() Keep things consistent. Ensure that the information each business unit gives to senior management is consistent. Different business unit managers may have different risk appetites and different perceptions of risk. A consistent reporting framework will assist here.

Keep things consistent. Ensure that the information each business unit gives to senior management is consistent. Different business unit managers may have different risk appetites and different perceptions of risk. A consistent reporting framework will assist here.

![]() Dig down to the roots. Insist that any breakdown in a core process or breach of an internal code of practice is analyzed in depth to identify the root cause and correct it. Individuals who are responsible must be held accountable.

Dig down to the roots. Insist that any breakdown in a core process or breach of an internal code of practice is analyzed in depth to identify the root cause and correct it. Individuals who are responsible must be held accountable.

Refocus your risk management function

![]() Clarify the TIRM function’s role. Once the business units are in control of the risks they are taking, the risk management function can concentrate on what it should be doing—namely, providing information, advice, and assurance. Its remit should ensure that it is not continuing to assume the responsibilities the operational managers should be handling.

Clarify the TIRM function’s role. Once the business units are in control of the risks they are taking, the risk management function can concentrate on what it should be doing—namely, providing information, advice, and assurance. Its remit should ensure that it is not continuing to assume the responsibilities the operational managers should be handling.

![]() Listen and learn. The TIRM function’s first task is to identify and interpret any changes in the external environment including changes in the expectations of external stakeholders. Ensure that it keeps abreast of all new developments.

Listen and learn. The TIRM function’s first task is to identify and interpret any changes in the external environment including changes in the expectations of external stakeholders. Ensure that it keeps abreast of all new developments.

![]() Assess and advise. The TIRM function also has a key role to play in developing an information risk framework by giving the business units feedback on the effectiveness of the controls they are using and helping them to modify those controls where necessary. The risk management function should assess how the risk management processes the business units have established are performing. What progress have they made? What gaps remain and how should they be closed?

Assess and advise. The TIRM function also has a key role to play in developing an information risk framework by giving the business units feedback on the effectiveness of the controls they are using and helping them to modify those controls where necessary. The risk management function should assess how the risk management processes the business units have established are performing. What progress have they made? What gaps remain and how should they be closed?

![]() Tell the truth—be honest about risk; do not bury bad news. The TIRM function’s final duty is to check that the business units are doing what they claim and let you know what is really happening. That, in turn, means ensuring it has sufficient authority and mandate to talk to senior management on an equal footing and challenge the existing order where necessary.

Tell the truth—be honest about risk; do not bury bad news. The TIRM function’s final duty is to check that the business units are doing what they claim and let you know what is really happening. That, in turn, means ensuring it has sufficient authority and mandate to talk to senior management on an equal footing and challenge the existing order where necessary.

![]() Get it right. Putting information risk management back where it belongs—with business units and individual employees—enables the organization to create a lean information risk management function with lower overheads. More importantly, it helps to build a business that is as unsusceptible to risk as it can possibly be—that is, a business that is effective and efficient.

Get it right. Putting information risk management back where it belongs—with business units and individual employees—enables the organization to create a lean information risk management function with lower overheads. More importantly, it helps to build a business that is as unsusceptible to risk as it can possibly be—that is, a business that is effective and efficient.

![]() Never forget the importance of culture. What is promulgated above will not succeed unless the right organizational culture is in place.

Never forget the importance of culture. What is promulgated above will not succeed unless the right organizational culture is in place.

By following the four steps outlined in the report, an organization will be ensuring that accountability for information risk exists throughout the various different business units. Recognize that all employees have an important role to play, an important contribution to make, and that they are fully engaged in embedding TIRM in the organization.

Summary

As with all initiatives that require a change of mindset and thinking in organizations, the introduction of the TIRM process will face organizational resistance from different stakeholders within your organization. Overcoming individual and cultural resistance is probably the biggest challenge you will face when implementing the TIRM process. This chapter presented established strategies to overcome organizational resistance and increase employee support for TIRM.

References

1. Deal TE, Kennedy AA. Corporate Cultures: The Rites and Rituals of Corporate Life. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley; 1982.

2. Hofstede G. Culture’s Consequences: International Differences in Work-related Values. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage Publications; 1980.

3. Hofstede G, Neuijen B, Ohayv D, Sanders G. Measuring Organizational Cultures: A Qualitative Study across Twenty Cases. Administrative Science Quarterly. 1990;35:386–396.

4. Johnson G. Managing Strategic Change—Strategy, Culture and Action. Long Range Planning. 1992;25(1):28–36.

5. Kotter JP, Schlesinger LA. Choosing Strategies for Change. Harvard Business Review. 1979;57(2):106–114.

6. Pascale RT, Athos AG. The Art of Japanese Management. New York: Warner; 1981.

7. Peters TJ, Waterman RH. In: Search of Excellence: Lessons from America’s Best-run Companies. London: Harper and Row; 1982.

8. PriceWaterhouseCoopers. Hands Up! Who’s Responsible for Risk Management? 2009; Available at www.pwc.com/getuptospeed; 2009.

9. Schein EH. Organizational Culture and Leadership. San Francisco: Jossey Bass; 1985.

10. Trompenaars F, Prud’homme P. Managing Change across Corporate Cultures. London: Capstone; 2009.

11. Tylor EB. Cited in Brown, A. (1998) In: Organizational Culture. 2nd ed. London: Financial Times Management; 1871.