Hacking Happiness: Why Your Personal Data Counts and How Tracking It Can Change the World (2015)

[PART]

1

Be Accountable

IDENTITY AND MEASUREMENT IN THE CONNECTED WORLD

NEVER CONFUSE MOVEMENT WITH ACTION.

—Ernest Hemingway

1

YOUR IDENTITY IN THE CONNECTED WORLD

I have preserved my identity, put its credibility to the test, and defended my dignity. What good this will bring the world I don’t know. But for me it is good.

VÁCLAV HAVEL

THE “CONNECTED WORLD” has three meanings in this book:

· The Internet

· The Outernet

· How we relate to one another as people

The Internet you know from using it on your computer. You’re probably also used to it living on your phone, and the concept of your car having Internet access is becoming familiar. But as a rule many think the Web is something that turns on and off with our computers, as we’ve become so used to it being in our lives. Unless Wi-Fi is down, we turn to the Internet and it’s there.

The Outernet refers to the combination of technologies affecting you away from your computer. Your mobile phone contains many of these—GPS, an accelerometer, a microphone. But there are also technologies referred to as the “Internet of Things,” which include sensors and devices in cars, buildings, and the world around us that we typically don’t see.

You’re aware of how your behavior is tracked on the Internet. Cookies are placed when you visit websites, leaving a digital trail that reflects who you are. In the Outernet, tracking happens the same way, but you’re less aware of its effects, many times because of its mundane nature. If you live in the Northeast, you likely have an E-ZPass, a device you place in your car to speed toll collection. Instead of slowing down to pay an attendant, you choose the lane that automatically deducts the highway fee from your bank account. You don’t think, “I’ve just left a point of data reflecting my identity” when you do so, but that’s the case. The time and location of when you were driving directly tied to your finances is registered in an instant. A little piece of you is recorded for the rest of time.

The more the world is connected around us, the more snapshots of our behavior are recorded to form a picture of our digital, or virtual, identities. And soon technologies like augmented reality, in the form of Google Glass or dozens of other wearable devices, will allow us to see other people’s data. How this will happen culturally is less clear than how the technology will work, but suffice it to say your actions in the Connected World will start to more directly affect your reputation and your well-being.

Well-being in the Connected World has three components:

· Subjective well-being—how you perceive your happiness and actions

· Avataristic well-being—how you project your happiness and actions

· Quantified well-being—how devices record your actions reflecting your happiness

These are critical distinctions that relate to other central themes in the book.

Taking a subjective measure of your happiness means I ask you to rate your perception of your mood in the moment. Your response, indicated typically as a number on a scale,1 reflects your truth. You may inflate your score due to survey bias, but when asked under the right circumstances, measures of subjective well-being provide a powerfully transparent way of assessing people’s perception of the world around them.

Avataristic well-being refers to how we broadcast ourselves, largely in the realm of social media. As an avatar is a manifestation of your character or alter ego in digital format, you can nurture or ignore it as you see fit. But the more engaging content you offer to online followers, the higher search rankings you’re likely to get. When people pass on what you say or share, your online influence increases as a reflection of activity associated with your identity.

This is the realm of Klout and dozens of other similar companies working to measure online influence. These tools provide the benefit of breaking through the massive amounts of online content to identify people focused on particular subjects who have a significant following. “Significant” refers to the number or scale of people following an influencer or the demographic makeup of those followers.

Measuring influence in this way is of particular interest for brands. Identifying potential evangelists for products and services can be as simple as approaching top influencers in a category. Critical advertising dollars can go to increasing the scale of a message via an influencer versus building up a unique online following for the brand. Sentiment analysis of people’s responses to messaging utilizing social analytics tools lets brands rapidly analyze how their marketing messages are faring with the audiences of the influencers with whom they’ve partnered. And all of it, the whole process, is tagged and ranked in search engines.

Klout and the like are not simply popularity mechanisms. Ranking via influence has direct impact on commerce, as reflected by where you appear in search. You may be the deepest-thinking mommy blogger on the planet, but if you don’t show up on the first page of a Google search, then you’re invisible.

Quantity of content is also a key indicator of influence. While it’s assumed the quality of someone’s tweets or posts is of a caliber to gain a large audience, the nature of following online is highly subjective. In this sense, we’re encouraged to always create fresh content over and above if we have anything relevant to say. Increased productivity fuels the insatiable drive for salable data in the current model of the Web.

Christopher Carfi is VP of platform products for Swipp, a social intelligence platform company focused on measuring sentiment. He gave a talk with Robert Moran of the Brunswick Group for the World Future Society called “Rateocracy: When Everyone and Everything Has a Rating”2 that touches on these ideas of influence. Moran’s definition of rateocracy focuses on the ease with which people can create digital versions of their thoughts or feelings for others to see in the future—a global sentiment stream that can give the pulse of the planet. However, as Carfi points out, these sentiment streams provide a different form of benefit than influence measures like Klout.

There are a number of tools that use opaque algorithms in order to try to determine the level of “influence” an individual has in a social network. Unfortunately, these types of systems are easily gamed, often relating “influence” to frequency of social network posting activity. In contrast, future rating systems aggregate the feedback of large numbers of individuals to create a comprehensive picture of what various constituencies think about the world around them. Instead of trying to predict influence, the future of rating systems is more about better decision making at various levels of granularity. For example, if one was in the market for a new car, you might not care about what the auto critics think about that car. Instead, you might want to know what your friends who owned that model thought of it, or what the sentiment on that model was from others who had a family with similar demographics to your own.3

This form of crowdsourced rating system is becoming more common in the form of Yelp or other networks people have come to rely on in our digital age. However, modern behavior has still led a large majority of people to utilize digital sites to express opinions in hopes of peer approval. And when our primary focus for networking becomes the need to increase influence, we invariably suffer by comparison. LiveScience magazine describes this dilemma in “Facebooking and Your Mental Health.” Author Stephanie Pappas cites recent research, pointing out the ironic fact that having too many friends on Facebook can lead to depression when people compare themselves with others’ achievements. While the site itself isn’t harmful, it’s leading many users to feel worse about their own lives after using it.4

Here’s a deep connection in the measures of online influence and wealth: When either is pursued only as a means to itself, people lose a balanced vision of what brings well-being. Klout and the GDP aren’t evil. They’re simply inefficient measures of holistic value for a person or a nation. The drive for increased influence or productivity alone becomes exclusionary for those who don’t have resources relevant for improvement.

Kids are a part of the growing group of people without adequate resources to deal with identity issues in our modern digital environment. Along these lines, I interviewed Howard Gardner, Hobbs Professor of Cognition and Education at the Harvard Graduate School of Education, best known for his theory of multiple intelligences and education reform. His book The App Generation: How Today’s Youth Navigate Identity, Intimacy, and Imagination in a Digital World provides deep insight into how kids relate to software applications and how apps can increase creativity and a strong sense of identity when viewed beyond the often limiting ways they’re designed to be used. I asked Gardner how apps were shaping identity for kids in regard to influence issues.

Social media like Facebook encourage individuals to “package themselves” so that they look as good, as perfect as possible. Not only does that inhibit exploration of identity, but it also makes youths feel inadequate, because they cannot live up to the apparently perfect lives of their peers. Of course, there were “role models” in earlier times, including ones taken from TV, but they were far more remote; one could not interact with them, and they did not change several times a week!5

The stress involving upkeep of one’s avataristic well-being is affecting us at an early age. Kids aren’t allowed the time needed to understand identity issues, let alone know how to fabricate a perfect persona online.

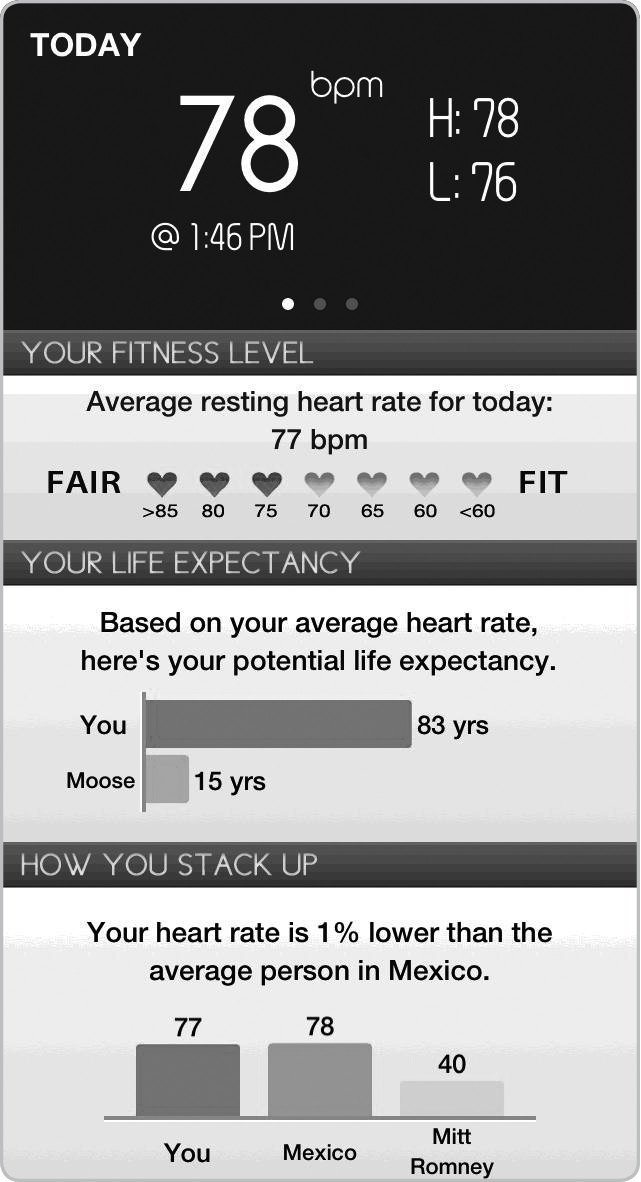

Quantified well-being in the Connected World refers to how data is collected about a person that can be uniformly measured. For instance, the iPhone app Cardiio measures your heart rate as indicated by a change of color in your face via reflected light not visible to the human eye. The data is aggregated to a dashboard allowing you to share it or compare it with others. One can question the accuracy of the tool, but if it matches up to other modes of collection you can log your heart rate as an objective, quantified measure.

What becomes fascinating regarding your well-being and digital identity is when you start to compare more than one quantified data stream. Where it would be possible to create a longitudinal study, or repeated observations over a long period of time about the same variables in an experiment, you could start to see patterns that could lead to insights when comparing relevant data points.

A simple experiment would be running along the same route every day for a year and taking your heart rate at the same locations along the way. If you utilized your GPS data to track your location, time, and date stamps, patterns would emerge demonstrating which parts of the track spiked your heart rate. You’d see that the point in time at which you ran also affected your results (after a meal, late in the day). If you incorporated weather data in the mix, you might see how atmospheric pressure affected your runs and health.

I conducted a highly nonscientific test to show how emotions, or quantified happiness, may someday end up in the mix of measuring well-being. I used the Cardiio app and took my resting heart rate (see below) and got a reading of seventy-eight. Then, without moving from my chair, I watched Kmart’s Ship My Pants6 commercial on YouTube. (It’s really funny; it involves multiple people saying “I shipped my pants” so you think they’re saying something else.) My heart rate after watching the video once was seventy. By the third viewing (I was guffawing at this point), my reading was fifty-two.

Does this prove I’ve quantified happiness in some way? Not at all, but it’s a start. Keep in mind I only used one data point—my heart rate—to measure my reaction to the video. If I used an app like Emotion Sense, I would also get time-stamped data relating to my mood and the tone of my voice. If I utilized a service like WeMo with home automation technology and utilized their motion sensors, I could send a text to my wife if I slapped the table hard enough while laughing. We’ll get to the point when we may feel machines know our emotions better than we do.

Note that my lowered heart rate finding due to smiling does have scientific precedent. In “De-Stress in Three Seconds,” author Cassie Shortsleeve reports about a study conducted by Sarah Pressman and other researchers from the University of Kansas in which college students were asked to hold chopsticks in their mouths to simulate a smile before facing a stressful situation. Compared to their non-chopstick counterparts, smilers had lower heart rates and reduced stress, leading researchers to believe the physical triggering of facial muscles to smile sends a message to your brain that says, “You’re happy—calm down.”7

So what if I did a longitudinal study around my Cardiio experiment for a year, adding in whatever sensors I could think of? Would there come a point where I could prove to you that a certain amount of data proved I was experiencing a certain emotion? Probably. Keeping in mind, as in the case of taking a survey, that I know I’m recording myself and have a bias toward laughing.

But my point is not to quantify emotion for its own sake. My goal is to demonstrate how intimately connected we are to the data we’re outputting and capturing in ways we’ve never done before. Mobile and home sensor technology is fairly cutting-edge, as is the trend of average consumers being able to capture their data. And remember, data is a currency. People pay for it. Think how Kmart’s PR value would go up if they could prove that a thousand people doing my Cardiio test watching their commercial lowered their heart rates over time and significantly improved their health.

The idea may seem far-fetched until you hear about a company like Neumitra, featured in the MIT Technology Review article “Wrist Sensor Tells You How Stressed Out You Are,” written by David Talbot. Neumitra has a device called bandu that’s compatible with smartphones that can measure stress via increased perspiration or elevated skin temperature.8 To research the piece, Talbot wore the device and tried to recite the alphabet backward in front of a group of strangers, resulting in his stress increasing by 50 percent as measured by wrist sweat and temperature.

Companies like Affectiva have also developed technology along these lines to recognize human emotions in the form of facial cues, letting brands test to see whether ads are engaging with consumers.9 Much like my Kmart example, if a thousand people watching a certain video don’t laugh as measured by Affectiva, it’s a good sign the commercial is a clunker. I see this model moving to the social TV arena,10 which is the trend of people interacting with live television programs or with other fans during prerecorded shows.

Whether facial recognition technology employed by Affectiva or Microsoft Kinect is reading our expressions during a show or our phones are measuring our reactions, our emotional output will be captured in one form or another. In terms of measuring stress, I think about watching a show like 24 and wonder at what point the TV would shut off if my heart rate got too high. Or when I’d get a call from my insurance carrier telling me to watch Modern Family to calm down before my rates got increased.

The emergence of quantified tracking of behavior signals that the avataristic form of well-being is fading in importance. While people will always follow influencers and repeat what they say, as we grow more comfortable with our actions being tracked, we’ll be able to quantify emotions, or at least agree on the proxies for emotion based on physiology. Our actions will reveal our true characters. And reputation will more closely mirror our true selves versus the avatars we currently broadcast to the world.