Hacking Happiness: Why Your Personal Data Counts and How Tracking It Can Change the World (2015)

[PART]

1

Be Accountable

2

ACCOUNTABILITY-BASED INFLUENCE

In the twentieth century, the invention of traditional credit transformed our consumer system and in many ways controlled who had access to what. In the twenty-first century, new trust networks and the reputation capital they generate will reinvent the way we think about wealth, markets, power, and personal identity in ways we can’t yet even imagine.1

RACHEL BOTSMAN

MY MOM RECENTLY decided to move, now that it’s been two years since my dad died. After decades of meticulous financial record-keeping and making payments on time, she learned she had to restart her credit score from scratch as a widow. Reminiscent of the gaping flaw in the GDP of not measuring women as primary caregivers, this practice also highlights the need to overhaul an outdated system.

Credit reporting’s history began more than a century ago, beginning with small retailers banding together to trade financial information about their customers. The early credit associations often focused on collecting negative financial information about people as well as data about sexual orientations and other private behavior. Oftentimes it was this private information that would justify associations’ denying services, reflecting negatively on people’s reputations.

Not exactly a hallowed past regarding our financial forefathers.

Just as harrowing as this fiscal bigotry from credit associations was their lack of transparency. As Malgorzata Wozniacka and Snigdha Sen noted in their article “Credit Scores: What You Should Know About Your Own,” it wasn’t until 2001 that people could gain direct access to their credit scores.2 This created a precedent for opaque collection practices around consumer information that data brokers have emulated in the online world. We have time in our Connected World, however, to wrest data back from brokers and control our identities and fates.

I wrote a piece for Mashable in 2011 called “Why Social Accountability Will Be the New Currency of the Web.”3 I was fascinated with online networks that had measurements reflecting trust generated by action where ratings were based on what people had done versus just how they were perceived as people.

One of the first places I looked was in the business world. Measuring performance is not a new idea, but typically it’s only managers who rate employees based largely on their productivity. New models have emerged, however, that aggregate peer-to-peer comparisons to form a picture of someone’s overall accountability, or reputation. One of these is Work.com, formerly known as Rypple and now a part of Salesforce.com. For my piece, I interviewed Nick Stein, who, at the time, was director of content and media for Rypple and is now senior director, marketing and communications, at Salesforce.com. A “social performance” platform, Work.com aggregates positive feedback (in the form of recognition) provided by colleagues. This recognition appears on an individual’s social profile, providing a snapshot of that person’s capabilities—as determined by their peers—thereby contributing to their reputation at work.

I asked Stein if he saw a day when someone’s Work.com score could become portable, meaning it would follow an employee from one job to the next. While he felt the number of variables dependent on the context of one organization might not translate to a second one, he did feel measures like Work.com would have an influence on reputation.

As we move toward a more social and transparent workplace environment, influence is becoming less dependent on your place in the org chart and more on the real, measurable impact you have on your colleagues. The idea is that all ongoing feedback, both positive and constructive, helps build an employee’s real reputation at work . . . This enables individuals to develop influence based on their real impact rather than a perception of where they sit in the company hierarchy.4

I want to focus on Stein’s idea of “real impact” now that the Connected World includes technology from sensors allowing quantified measurement. In the same way that brands will measure our emotional responses while watching TV, employers could track employees’ moods or physical data as a reflection of corporate culture or performance. Right now it may be creepy to think of intimate data being visible to employers or peers, and employment policies need to protect information about sensitive medical conditions or other data people don’t want to share in a work environment.

But let’s examine the rise and implementation of social media in the workplace as a precedent for how sensor data could be adopted in the future. When social media first arrived, privacy was of huge concern but didn’t keep the medium from becoming a mainstay of modern communication.

I began pitching the idea of blogs or podcasts for the business world in 2005, followed by Twitter, Facebook, and the like as soon as they became available. I sat in dozens of meetings where IT specialists warned about people using their own phones and devices at work, and managers expressed concern with employees wasting time on social media. I attended and spoke at hundreds of meetings and conferences discussing these issues and the merits of utilizing social media at work.

I think it’s safe to say social media in various iterations has now been universally adopted for the workplace. Social media policies are in place, employees know the distinction between their public and work personas, and brands understand the vital importance of engaging with consumers where they get their media. I don’t even use the term “social media” anymore—it’s simply “media,” and it’s all social. The process of this adoption of social media in the enterprise has taken roughly a decade.

This precedent of technology focused on our identities in the form of social media will expedite the adoption of sensor data in the workplace.

In 2006, Hitachi approached the MIT Media Laboratory Human Dynamics Group to investigate the opportunities for “social sensors” in the enterprise. The resulting research in Sensible Organization provides a fascinating sense of how wearable and proximity sensors could affect the workplace. Part of the research focuses on how social sensors allow employees to visualize aspects of behavior revealed through these technologies. For instance, sensors could reveal which employees are more socially connected in an office, giving managers a way to quantify how best to disseminate communications to their organizations. Employees could also see how their activities could better dovetail with colleagues to increase their effectiveness at work.5

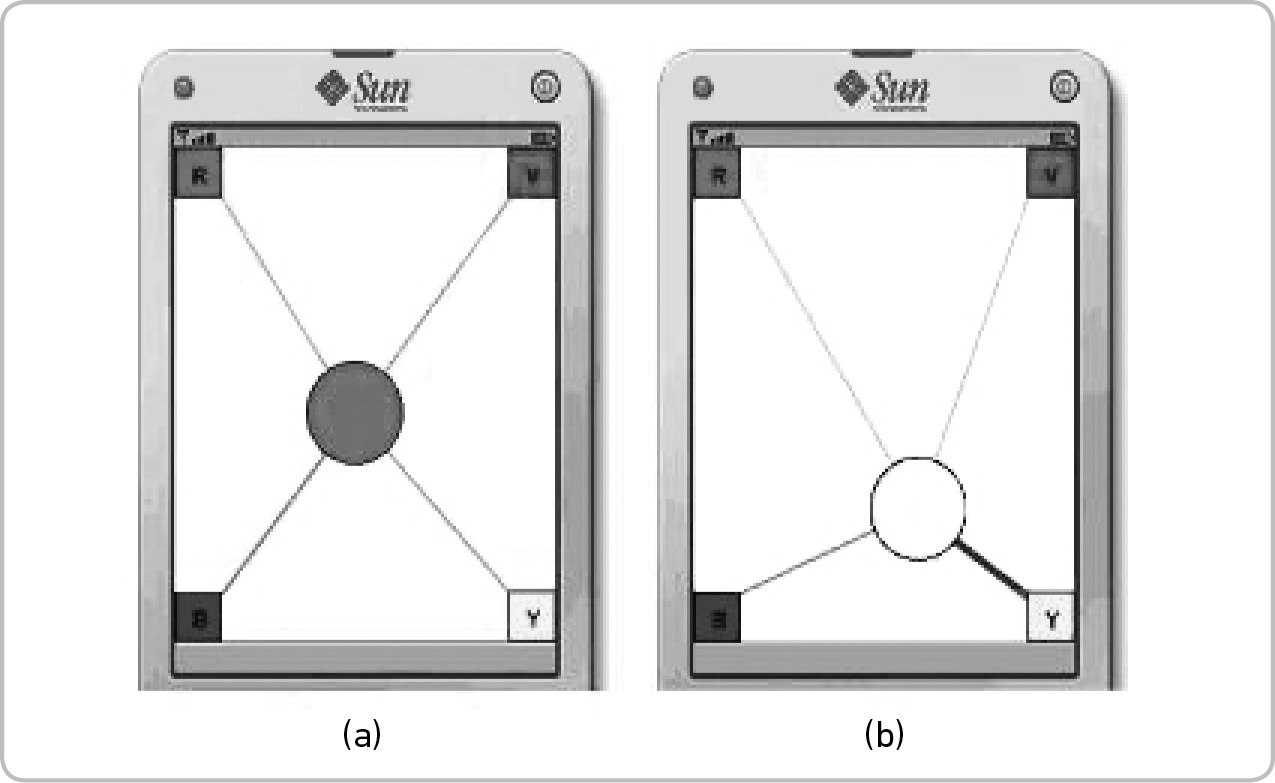

A more recent study of social sensors in the workplace from MIT, “Sensible Organizations: Technology and Methodology for Automatically Measuring Organizational Behavior,” provides other pragmatic examples of technology utilized to improve dynamics among employees. Of particular interest is the “meeting mediator,”6 which uses sociometric badges (lanyards worn by employees measuring vocal tone and proximity) to help people understand how they’re participating in a conversation. Displayed on a tablet or computer, employees are represented by shapes that equate to their physical location in a room. Depending on how often they speak and for how long, color patterns shift in the meeting mediator display, reflecting patterns in the conversation.

Fig. 1. Meeting mediator is an example of a mobile phone-sociometric badge application. Each square in the corner represents a participant. The position of the center circle denotes speech participation balance, and the color of the circle denotes the group interactivity level. Fig. 1(a) shows a well-balanced and highly interactive group meeting, whereas Fig. 1(b) shows that participant Y is heavily dominating the conversation with a low level of turn taking between the participants.

When people get used to the dynamics of seeing their conversations visualized in this way, this could become a powerful tool to combat the well-documented effect of meetings being dominated by certain personality types.

Accountability-based influence will begin to look a lot different in the coming years with the adoption of these types of methodologies. But along with privacy concerns, let’s focus on the positive for a moment. Think about the meeting mediator being adopted where you work. How many conversations have you not contributed to because a domineering colleague wouldn’t stop talking? Or if you’re like me (passionate and verbose), how would your work benefit from letting others contribute more to a meeting? If a visual aid encouraging them to speak would help them feel more appreciated, they’d be more likely to find meaning in their jobs. Taken to scale, multiple employees with this type of tool may feel more loyal toward an organization. This could result in lower attrition rates, providing a measurable return on investment (ROI) for an organization.

Similarly, I wonder how a device like Neumitra’s bandu stress bracelet could be utilized for the workplace. Imagine if a particularly nasty manager’s team of employees all wore the bandu for three months. Combined with proximity and voice analysis sensors, data could show when and how the manager interacted with his employees. Data from voice sampling might indicate a majority of meetings involved raised or angry tones. Data from stress sensors might indicate a majority of employees had stress levels that directly correlated with these raised tones.

It’s not rocket science—the data is simply reporting a visualization of the manager’s negative management style. More important, however, is the quantified data providing a record that the manager is adversely affecting the health of his employees. In the near future, measures of ROI or quarterly reporting will need to take into account whether a manager is contributing to the positive or negative health of their employees. Ongoing high stress levels could increase a company’s health insurance rates. In a world with sensors, manager accountability gets quantified.

Let’s take the opposite situation. A manager utilizing empowering feedback for their team uses the same technology, potentially coupled with a Cardiio heart monitor for added data value. In direct contrast to the other example, insights gained from time stamp data could show an employee who exhibited high levels of stress had their anxiety lowered because of meeting with their manager. If they measured their resting heart rate before and after the meeting, data might show lower numbers for employees correlating to better health. In this scenario, our positive manager could be rewarded for improving morale, employee health, and saving the company money on their premiums.

I learned about the mobile technology agency Citizen after reading about them in the Wired article “What if Your Boss Tracked Your Sleep, Diet, and Exercise?”7 The company has begun utilizing various sensor tools to measure employee health as a way to improve productivity. I interviewed Quinn Simpson, user experience director at Citizen, to discuss how he maintains a balance between privacy and innovation in his work. The team testing the implementation of sensors with Simpson are voluntarily providing data about their health, recognizing that it will take time for some colleagues to feel comfortable sharing various data. The company benefits from a strong corporate culture and a young demographic that is comfortable utilizing social media.

I asked Simpson about the idea of sensors with managers who might be overly negative (this is not a technology they’re currently providing, but might in the future). His perspective was on the potential value of measuring performance via multiple data points as a great indicator of employee burnout. Pushing staff too hard on an extended basis, especially in a creative setting like Citizen, could lead to high turnover and loss of productivity. As Simpson noted:

Because we keep track of what projects people are working on, we want to be able to look at data regarding their output and see when they risk burning out. Correlating relevant information points like this means you know when someone is not being as productive as they could be. So if I’m working too long on a project, both my manager and I want to know.8

What’s encouraging about this example is how sensors and data promote unity among the staff. If a manager can quantify when a star creative is heading toward burnout, they can ask the employee to go home early or head to the gym. They will have data supporting their actions that better sustain their organization for the long term. Likewise, if identity or reputation models exist in their organization, they may earn more trust from employees for making a smarter choice for long-term gain versus short-term profits.

The New Reputation Economy

While I’ve focused on measuring accountability at work, it’s easy to see how the technology explained in my earlier examples can live outside the enterprise. In a world with finite resources, we may soon enter a time when we’ll see “sensible governments” utilizing technology that measures citizen behavior in an effort to improve their lives. While it’s easy to consider this to be a Big Brother situation, where we’ll be spied on at all times, let me describe a more supportive scenario that could come to pass in our Connected World.

There’s a one-hundred-million-ton collection of plastic particles eddying about in the ocean known as the Great Pacific Garbage Patch.9 While the particles are very small and the ocean has high powers of self-restoration, we’d still be well advised to increase our focus on recycling. In the same way that Work.com has a rating for employees to evaluate peers, what would happen if citizens began evaluating one another based on their recycling efforts? Or what if the sensor environment around citizens could contribute to a person’s accountability rating as well?

Let’s say you buy a bottle of water at the convenience store. Mobile payment technology charges your debit card but also indicates the bottle is made of plastic from its bar code and should be recycled. A time and date stamp with that information is sent to your town’s local recycling facility. Let’s say the facility has done a study and gathered enough data to know that your town’s average length of time between buying a bottle of water and consuming it is one week. After seven days, if you haven’t recycled your bottle, you might get a text reminding you to do so. If you’re storing the water, you could indicate that in your response.

Citizens who recycled on a regular basis might receive a tax break at the end of the year because their efforts meant the town would receive money paid for bottles returned in bulk. But if you opted to chug your water and chuck the bottle in the parking lot, you might get a small fine for not recycling properly. If you left the bottle in a wildlife preserve as indicated via your GPS, you might get a larger fine. If your “recycling reputation” dropped low enough, retailers might be banned from selling you certain products.

It’s not fun thinking negatively. But it’s also not realistic to think our actions in the Connected World won’t have negative consequences depending on the context. Where a community agrees on the types of things to measure and how privacy can be respected regarding data collection, more positive than negative results will occur.

This notion of communal benefit is reflected in a focus on sharing with the rising trend of collaborative consumption, a term introduced in 1978. Rather than drive individual consumerism, collaborative consumption encourages distribution of goods, skills, or money in peer-to-peer networks to preserve natural re-sources and lower individuals’ costs for items they can share. Com-panies like Airbnb encourage home swapping, and Zilok enables rentals between individuals for everything from power tools to game consoles. Sharing and rating provide a robust platform for accountability and reputation models to emerge, buoyed by the advent of the Web.

As the Economist notes in “The Rise of the Sharing Economy,” “Before the Internet, renting a surfboard, a power tool, or a parking space from someone else was feasible, but was usually more trouble than it was worth. Now websites such as Airbnb, RelayRides, and SnapGoods match up owners and renters; smartphones with GPS let people see where the nearest rentable car is parked; social networks provide a way to check up on people and build trust; and online payment systems handle the billing.”10

If personal data can remain protected in these systems of open innovation, the sharing economy is a powerful move toward fulfillment in the Connected World and a positive example of how accountability-based influence can foster community versus self-focused gain.