Hacking Happiness: Why Your Personal Data Counts and How Tracking It Can Change the World (2015)

[PART]

1

Be Accountable

5

QUANTIFIED SELF

Wearable computing devices are projected to explode in popularity over the next year and, with a wave of new gadgets set to hit the consumer market, could soon become the norm for most people within five years. ABI Research forecasts the wearable computing device market will grow to 485 million annual device shipments by 2018.1

ABI RESEARCH

WE ALL CURRENTLY have wearable computing devices in the form of our smartphones. Slap a piece of Velcro on your iPhone and wear it on a headband and you’re good to go. In terms of history, if you wore an abacus on a necklace back in the day, you’d also technically be part of the wearable computing movement.

In a similar fashion, quantified self as a practice has been happening since time began. When Eve asked Adam, “Does this fig leaf make me look fat?” she was comparing herself to a previous measurement. If you’ve used pencil and paper to figure out your finances, that form of self-tracking also fits the bill (pun intended).

Quantified self (QS) is a term coined by Kevin Kelly and Gary Wolf of Wired in 2007. It refers to the idea of self-tracking, or “life-logging,” as well as the organization by the same name that helps coordinate hundreds of global meet-up groups around the world. According to the group’s website, the community offers “a place for people interested in self-tracking to gather, share knowledge and experiences, and discover resources.” Wolf wrote a defining piece about the notion of QS in the New York Times Magazine in 2010. In “The Data-Driven Life,” Wolf describes how improving efficiency is not the primary goal for self-trackers, as efficiency for an activity requires having a predetermined goal. Trackers pursue insights based on data collected in real time, where more questions may develop as part of an overall self-tracking process.2

This notion of collecting data with an unknown goal strikes most non-trackers as odd. In a world that typically rewards productivity above all, how could someone spend so much time measuring his or her actions with no set goal in mind? As with data scientists, self-trackers look for patterns in their actions to form insights versus approaching the data with hypotheses that could color the outcome of their findings.

Measuring your actions without a set goal in mind is hard. We’re trained to think that all of our actions must have a defined purpose resulting in improved productivity. I remember years ago working in a high-end café and getting admonished by my manager because she felt I was moving too slowly. She taught me how to look around the café and quickly assess multiple tasks that needed to be done based on walking clockwise around the room. The lesson stuck with me. To this day I still use this technique in my own kitchen, although the only patrons I need to take care of are my kids getting ready for school.

The downside of this type of harried productivity, however, comes in the toll it can take on your psyche. It’s very difficult not to gauge your success as defined by others, and the plethora of self-help guides touting increased productivity only adds to the stress.

We’re coming into a time, however, when the aggregation of our data will help us automatically become more productive. Analyzing patterns and offering recommendations based on behavior provide a huge increase in productivity and value via personalized algorithms (predictive computer equations based on past actions). Stephen Wolfram, a complexity theorist and CEO of Wolfram/Alpha, notes in an interview with MIT Technology Review that he stopped answering group e-mails in the morning because data showed the majority of the issues worked themselves out by the afternoon.3 Sound familiar?

Another key benefit Wolfram describes in the article is the idea of augmented memory, when the aggregate data of our lives will be made available to us at all times. Think of your life as if every word and action were an e-mail stored in a database, searchable in an instant—that’s the idea of augmented memory. The paradigm shift of fully augmented memory will have massive cultural repercussions, both positive and negative. Recording the experiences of our lives in photos and audio or video formats has been limited technically to this point due to battery life of hardware and lack of storage for content. Battery life is improving at a rapid rate, and the evolution of cloud computing (servers that access and store your data remotely, versus being stored on your hard drive) means if we can afford to pay for storage, it’s available. Augmented memory enabled by these technologies will provide for the following types of applications:

· You’re at a conference and someone you don’t recognize smiles and walks toward you. Using facial recognition technology, you can quickly scan past life-recordings to see how you know the person.

· You can run tests on your e-mails for the past year for keystroke data (how hard you hit the keys, serving as a proxy for anger/stress) and see what times of the day or week you tend to be emotional and how that affects people’s responses to your messages.

· You can cross-reference your GPS data with your e-mails, using sentiment analysis (technology that identifies certain words that infer positive, negative, or neutral language patterns) to identify the places where you are most productive.

These examples should show you why quantified self-analysis won’t stay only in the realm of life-loggers or health enthusiasts for long. Hacking H(app)iness, or owning your data in this context, isn’t just about protecting it—it’s about liberating it to be useful in ways it’s never been used before.

Objectivity in Action

Another aspect of self-measurement that’s a challenge for people is staying objective. There’s deep emotion tied to something like losing weight or keeping your house clean. But a key component to quantified self is the skill of articulated observation. I developed this skill over the years as a professional actor and writer. It takes practice to look at a person (or yourself) and simply record what you see. You would think stillness would be easy to achieve, but it’s actually very challenging. We are hard-coded toward bias and judging others. It’s in our DNA as a remnant from our ancient past when we relied on our fight-or-flight mechanisms to keep us safe.

Here’s an exercise you can try to cultivate your nonjudgmental observation skills. Record yourself on video standing and reading a passage of poetry or a passage of a play. Something you’re passionate about. Perform it. Have fun doing it and don’t worry about the caliber of your acting. The focus of the exercise is actually about your response to watching the video. If you cringe watching a recording of yourself, pretend you’re watching someone else and just describe what you see.

Most young actors (myself included) don’t realize how much energy is stored in their bodies that comes out when they recite a passage of a script until the first time they see themselves on video. For instance, “flappy hand” is a common occurrence with young actors: While saying lines from a scene, their whole body will remain unmoving but one hand will gesticulate wildly as if it’s caught on fire. A good acting teacher will point out the latent energy in the person’s hand and have the actor take a deep breath from their diaphragm (the power center for breathing versus your lungs/shoulders) before starting again. Typically after two or three repetitions of this exercise, “flappy hand” goes away and the actor delivers a more centered and powerful performance than before.

Observation is a powerful tool. A primary trait of a gifted actor is their well-honed ability to observe humans in action. As a young actor, you “play” a character—you want a quick laugh or to milk a dramatic scene and you try to coax a certain response from your audience. That’s death, because it’s fake. For instance, in a comedy, characters don’t think they’re funny. The audience laughs because they identify with the people in the play. A good actor will inhabit a character, without judging the person they’re playing and planning for a certain response. As a performer, they may genuinely feel terror in a role while the audience howls with delight.

Here’s a story along these lines from the world of acting. You’ve heard about Method actors so caught up in their roles that they fully believe they’ve become another person. That can happen, but these stories tend to be overblown. As a professional actor, you’ve got to show up for eight shows a week in theater or hit your mark in film or TV. It’s great to be Method and passionate, but if you lose touch with reality, you won’t continue to get hired. This pragmatic aspect of performance also relates to the idea of playing an action in a scene. For instance, you can’t “play” being sad in a scene—sadness is the result of not getting something you’re pursuing.

There’s a famous story of the renowned acting teacher and Moscow Art Theatre founder Constantin Stanislavski working with a group of young performers, teaching them the importance of playing an action in a scene. He asked one of his students to go onstage and sit in an armchair he’d placed there. Given no specific instruction, the young man sat and proceeded to make a series of faces that initially amused his classmates. As time wore on, however, the boy became flustered, unsure of what to do with himself. Nervous laughter from his friends faded into a tense silence. Stanislavski remained unmoving, watching with the rest of the class as a palpable sense of desperation exuded from the stage. After several more minutes, Stanislavski finally told the student he could sit down. The young man leapt back toward his seat, visibly relieved.

Then Stanislavski stopped. “Wait,” he said. “I seem to have misplaced my glasses. I believe they’re under the chair. Would you get them before sitting down?” The boy obliged, dropping to his knees and reaching under the chair. Then he removed the cushion, carefully examining to see if he’d inadvertently crushed the glasses by mistake. He continued looking for a few moments before Stanislavski spoke and said he realized his glasses had been in his pocket the whole time.

When the student sat down, Stanislavski revealed that the entire time the boy had been onstage, before and after looking for the glasses, had been a lesson in acting. When the boy pantomimed for his friends, he was going for an effect. When he was looking for Stanislavski’s glasses, he was pursuing an action. As Stanislavski noted to the class, when the student was actively en-gaged in trying to accomplish a goal, however mundane, he was riveting to watch.

This story illustrates a simple fact: Truth is revealed by action. The boy was initially uncomfortable because he was trying to fabricate an experience for his friends. This same principle applies to our lives and quantifying our actions. By taking action and measuring our data without judgment, we gain insights about our behavior we didn’t even necessarily set out to study.

But you won’t know until you start to measure.

The Numbers on the Numbers

The Pew Internet & American Life Project released the first national (U.S.) survey measuring health data tracking in their Tracking for Health report. Here are some of their top findings:

· 46 percent of trackers say that this activity [self-tracking] has changed their overall approach to maintaining their health or the health of someone for whom they provide care.

· 40 percent of trackers say it has led them to ask a doctor new questions or to get a second opinion from another doctor.

· 34 percent of trackers say it has affected a decision about how to treat an illness or condition.

Particularly interesting is information about how people handled their tracking:

Their tracking is often informal:

· 49 percent of trackers say they keep track of progress “in their heads.”

· 34 percent say they track the data on paper, like in a notebook or journal.

· 21 percent say they use some form of technology to track their health data, such as a spreadsheet, website, app, or device.4

These are some powerful statistics. Almost half of the people measured say self-tracking has changed their overall approach to help. That’s huge. While they track progress in their heads, the growing popularity of quantified self apps means technology will soon increase the number of people measuring and improving their health. Hacking H(app)iness in the form of health data is a great place to start seeing how valuable it can be to measure and optimize your life. However, QS goes beyond measuring just the physical components of your health data.

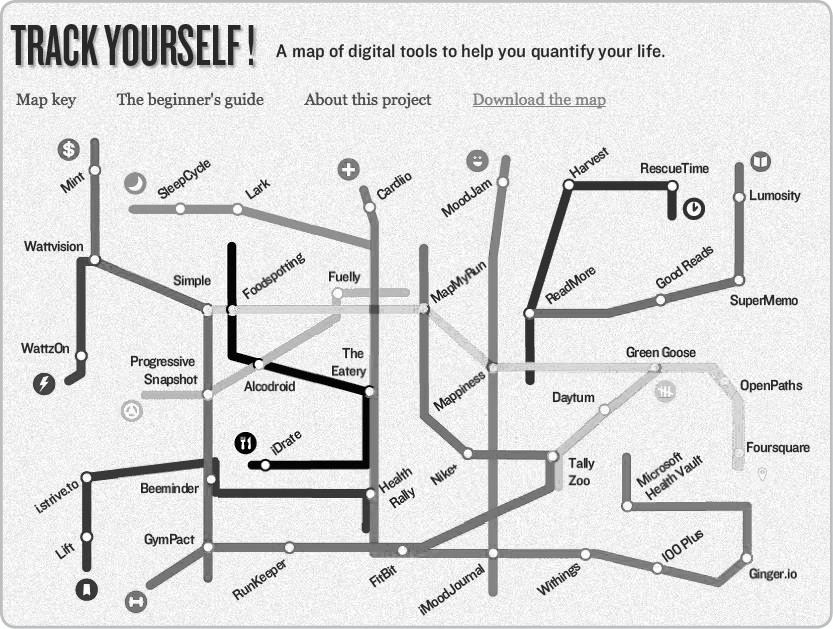

This Track Yourself image was created by Rachelle DiGregorio5 as part of her Track Yourself! project. Modeled after the London Underground, the different lines represent different verticals, or areas each quantified self app focuses on. The map provides a great visualization to remind the viewer how all of our behavior intersects at various points in our lives.

To get started on your own self-tracking journey, I recommend you check out the Quantified Self’s Guide to Self-Tracking Tools.6 At the time of writing, it contained 505 QS apps focused on everything from health and medicine to money and mood. Two of my favorite mood-focused apps are MoodPanda and MoodScope. MoodPanda is extremely popular, with over a million registered users regularly recording their emotions. MoodScope adds the unique and compelling feature of e-mailing your self-rated moods to friends in a model based on the “sponsor” model from Alcoholics Anonymous.

The first time I tracked behavior it was definitely empowering. It’s a digital declaration of sorts. But unlike a New Year’s resolution, you don’t have to feel crappy after you bail in four days because you’re looking for patterns that lead to bigger insights than “I like to eat a lot of bacon.”

If you want to get started with a great free tool to track yourself, try iDoneThis, designed for teams in a workplace. Simply write down what you did during the day in an e-mail that’s sent to you at six p.m. every evening. The company is focused on building software “you don’t have to remember to use” and lets you keep a digital diary that validates your actions or those of your team.

The Art of Doing Less

Ari Meisel’s life represents one of the most powerful stories I know in terms of applied life tracking. In 2007, he was diagnosed with Crohn’s disease, an incurable disease of the digestive tract. After hitting a low point in the hospital dealing wih multiple medications and discouraging results, Ari began focusing on improving his health with a combination of yoga, nutrition, and exercise. He also began optimizing, automating, and outsourcing daily activities to provide himself the time he needed to get healthy. Fast-forward a few years, and Ari was declared free of all traces of what is considered to be an incurable disease. He even competed in an Ironman competition in France in 2011. It’s a truly inspirational story.

Now Ari focuses on “Achievement Architecture,” working with clients to help them emulate his ability to optimize in various parts of their lives, something he calls the Art of Less Doing. Here’s an excerpt from one of his popular posts, “Don’t Try to Prioritize, Work on Your Timing,” that provides a great lesson for anyone thinking of how to track without the baggage of self-judgment:

Carpe Diem: This famous saying about seizing the day is actually part of a longer phrase, Carpe Diem Quam Minimum Credula Postero, which means Seize the Day and Put Minimum Faith in the Future. There will always be more tasks and more things that you need to get done. It would be foolish to think that simply arranging tasks in a pecking order will have any bearing on your productivity or your life tomorrow or even an hour from now . . . When it comes down to actually getting things done, we must live in the moment. You assign yourself a task at the relevant moment, you complete the task, and you move on. You don’t worry about what you have to do next because your system will “assign” it to you when the time comes. You are delegating the responsibility of worrying about these things to a system of productivity, the system of Less Doing.7

Technology can help us live more in the moment. Quantified self tools provide a path to help us study ourselves so, after we gain an insight about our behavior, we can optimize accordingly. We just have to get out of our own way to let it happen.

H(app)y and Healthy

As a way to provide more examples on how quantified self tools and other methodologies can increase your happiness and well-being, I’ve included an article I wrote for Mashable called “How Big Data Can Make Us Happier and Healthier.”8 My hope is that it will provide you with a number of ways you can Get H(app)y in your life.

HOW BIG DATA CAN MAKE US HAPPIER AND HEALTHIER

Big Data is getting personal. People around the globe are monitoring everything from their health, sleep patterns, sex, and even toilet habits with articulate detail, aided by mobile technology. Whether users track behavior actively by entering data or passively via sensors and apps, the quantified self (QS) movement has grown to become a global phenomenon, where impassioned users seek context from their Big Data identities.

Moreover, with services like Saga and Open Sen.se, users can combine multiple streams of data to create insights that inspire broader behavior change than by analyzing a single trait. This reflects a mixed approach design (MAD) research methodology that purposely blends quantitative and qualitative factors in a framework where numbers are driven by nuance. The science of happiness, for example, is now a serious study for business, as organizations combine insights of the head and heart to create environments where workers feel their efforts foster meaningful change.

However it’s studied, the desire to understand monitored behavior has reached a fever pitch, and the QS movement is attempting to meaningfully interpret our daily data.

The Power of Passivity

“We are moving towards a time when the ability to track and understand data is deeply woven into our daily lives,” says Ernesto Ramirez, community organizer for Quantified Self. “Sensors are becoming cheaper and connectivity is more ubiquitous by the day.”

This ever-present nature of data availability will become even more powerful when the general public begins to use apps that require little ongoing attention or input. Passive data collection is especially relevant in the health-care industry, for example.

“The data Quantified Self provides is not a replacement of any measurement to date—we haven’t had this type of measurement to date,” says Halle Tecco, cofounder and CEO of Rockhealth, the first seed accelerator for digital health startups. “Patients live very cautiously before trips to doctors, and this causes more trips to doctors. It’s better if physicians can get a more comprehensive view of people’s ongoing health.”

Tecco highlights the importance of passive monitoring. For instance, a mobile app can continuously measure glucose levels or other factors like heart rate over time. Spikes in those readings could immediately trigger a doctor, even remotely. “We can save money and improve outcomes by having data collection embedded in our everyday lives,” she adds.

Declaring Your Deeds

Nowadays, people are declaring their daily goals and intentions to peers and seeking their support via social media. Companies like Gympact and StickK operate on accountability-based influence (ABI), a scenario in which you’re judged on your actions versus your words. Beeminder, a “motivational tool that puts your money where your mouth is,” falls into this category too, according to cofounders Daniel Reeves and Bethany Soule. Users quantify a goal and pledge to pay money to Beeminder if they fall off the wagon.

“The platform lets users tweak their regimen at any time, with the caveat that any changes take effect with a one-week delay,” says Reeves, “so you can change your commitment, but you can’t change it out of laziness, unless you’re particularly forward-thinking about your laziness.”

According to Reeves and Soule, Beeminder is the only platform that combines the advantages of quantified self-tracking with a commitment contract, a compelling and self-binding form of digital declaration in which users risk a public pledge as a form of accountability for their goals.

Other companies in the QS space offer tangible ways to demonstrate action. A simple framework for tracking positive behavior is provided by uGooder wherein users gain badges for broadcasting good deeds they’ve completed. The service also lets users print a transcript of all the good deeds they’ve ever done using the platform.

“I thought someday this might be something people could take to a job interview or submit with a college ap-plication to show how much good they have done,” says Dan Lowe, uGooder’s creator. The idea is compelling—why shouldn’t employers or schools focus on overtly positive, community-supported behavior, versus an errant photo of high school revelry?

The rise of portfolio platforms like Pathbrite and LinkedIn’s volunteer profiles encourages people to professionally self-claim their positive behavior. The rise in ABI will eventually supplant trust networks built primarily on words.

The Advantage of Aggregation

“We are of the philosophy that data is versatile,” says Rafi Haladjian, cofounder of Sen.se. “Once you collect data from a source, you can decide how to use it later on.”

Haladjian seems more artist than engineer. He credits the muse of serendipity for guiding data in ways that maximize insights for enlightened users. Sen.se also proselytizes the “Internet of Everything” over the Internet of Things, supporting the idea of the interconnectivity of data when multiple passive sensors work in unison, versus one input alone.

“We need to create the culture of data mashups and we’re finding ways to make that easier,” he says. Demonstrating how to identify unique patterns via these mashups, Haladjian speaks of an elderly parent whose passive sensor placed in her favorite armchair measures how much time she spends sitting. The sensor is one of many placed throughout her home to gauge time spent in various locations or usage of different appliances, data the woman’s caretaker can use to measure her health.

In this instance, information is collected without its full purpose known beforehand. “If users start to simply collect data in this way,” notes Haladjian, “they can use all sorts of tools to discover the hidden meanings that lie behind the mundane.”

Esther Dyson, chairman of EDventure Holdings, also studies the concept of data mashing. Her concept of the quantified community interprets Big Data as a series of inputs, driven by individuals who wish to improve their communities and world. She describes her vision of quantified community in an article for Project Syndicate: “I predict (and am trying to foster) the emergence of a quantified community movement, with communities measuring the state, health and activities of their people and institutions, thereby improving them.”

For example, she says, when QS tools collect data about health, this data can and should be combined with local health statistics to generate new insights. She also notes the existence of civically minded apps like Street Bump that let users take photographs of or collect data around potholes or other citizen concerns.

This community focus shows how the QS movement can provide a new layer of qualitative data on top of quantified reporting. Think about an app wherein citizens could report their emotional state at seeing a pothole, as well as record its location. QS apps could easily aggregate these emotional tags with obvious economic repercussions. (If you look for good schools when buying a house, wouldn’t you also check the “emotional history” of a neighborhood as well?) Combine this tagging with the ability to search the virtual arena via augmented reality tools like Google Glass and it’s easy to see how the quantified community will usher in a transformative era of civic engagement.

Emotions in the Enterprise

“Altruism is alive and well on the Internet,” says Paul Marcum, director of global digital marketing and programming for GE and a driver of Healthy Share, a Facebook app that lets users announce health goals and use friends as sources of inspiration. “There is an opportunity to have users ‘pay it forward’ when they build themselves up by helping others,” he says.

The platform proves that the idea of quantified self has taken hold with brands and enterprise. Marcum points out that “sharing is a form of tracking,” that announcing actions via social media is akin to active monitoring via a QS device. “This is information people want to share, and we want to know how to capture that to spark behavior change,” says Marcum. Platforms wherein users are driven by intrinsic motivation and supported by a community let brands get out of the way and understand what truly drives a user base.

“Why is ethical integrity, why is character, not considered an economic asset in a time when trust and reputation are widely heralded as competitive advantages for companies?” asks Tim Leberecht, chief marketing officer of NBBJ, a global design and architecture firm, who while still at his previous role at Frog Design was a driver for the company’s Reinvent Business hackathon, an event to “create concepts and prototypes to help create a more social and human enterprise.”

In a post titled “Hope for the Quantified Self,” he refers to mounting evidence that shows well-being and happiness increase productivity and the bottom line. The result is organizations seeking to understand what truly makes employees happy, how to best blend qualitative along with quantitative metrics, a practice that may seem foreign to most corporate cultures.

Leberecht has a solution: “We need to find a way to measure the social value created by those whose contributions are outside of the common ROI vocabulary.”

He cites the CEO who inspires and instills hope for thousands of employees, but who has failed to meet the board’s growth expectations. “As hyper-connectivity and social networks tear down the boundaries between professional and private lives, only those who are complete will be able to compete.” Matching internal and external character, words and deeds, these new “whole selves” will no longer tolerate a chasm between idealism and pragmatism.

Leberecht’s observations point to a growing pressure for organizations to study happiness within the workplace. Corporate restrictions may soon lift to proactively embrace character traits from outside the workplace, and qualitative paradigms will gain the credibility of quantitative metrics.

“What if we were able to take the quantified use of metadata, a computing-based narrative of humanity, and integrate it with centuries of human narrative and storytelling?” asks Thanassis Rikakis, vice provost for design, arts and technology at Carnegie Mellon University. “That would provide a tremendous opportunity to understand humanity at a level that’s never been understood before.”

Rikakis is the founder of Emerge, an event that first took place at Arizona State University. Featuring noted science fiction writer Neal Stephenson and visionary geek Bruce Sterling, the event also brought together scientists, artists and designers. The primary goal was to bring together experts from multiple disciplines, recognizing that purely quantitative solutions can’t fully tackle the complex issues we’re faced with in the modern era.

Rikakis points out that QS technology allows us for the first time in human history to embed computing in every part of our lives. The value of the quantified self will be amplified when we recognize how qualitative measures complement Big Data.

For his work in interactive neurorehabilitation, Rikakis uses highly advanced tools to track forty-four kinematic parameters of the affected upper limbs of stroke survivors. He says data from these kinematic measures and their relation to functional outcomes is an essential step towards promoting recovery. But to be effective, this data needs to be combined with the qualitative observations of a therapist and filtered through the relationship of therapist-patient.

“We have to keep in mind that there’s information that does not go through data but via human interaction,” says Rikakis. “It goes from community to community and has a richness that’s hard to quantify.”

Don’t Worry, Be App-y

We’re in an era when sensor technology and the maturation of smartphones mean data is being collected about your actions in ways that have never existed before. There are no universal privacy and identity standards, which means your unwilling contributions to Big Data are being shaped by forces you can’t control.

The good news: Getting familiar with quantified self applications will benefit personal and community self-awareness. You’ll understand how to better shape your identity in this new virtual economy and learn the quantitative metrics that derive their fullest context when seen through a qualitative lens.