HCISSP Study Guide (2015)

Chapter 3. Regulatory Environment

Abstract

This chapter discusses the fundamental legal and regulatory requirements that govern healthcare information. It will also review the importance of policies and procedures used by the organization when protecting healthcare information during data exchange.

Keywords

Data breach regulations

HIPAA

HITECH Act

Information flow

Policies

Procedures

Standards

Compensating controls

Residual risk

Code of Ethics

This chapter will help candidates

![]() Understand the legal and regulatory environment for health information

Understand the legal and regulatory environment for health information

![]() Understand healthcare-related security and privacy frameworks

Understand healthcare-related security and privacy frameworks

![]() Understand regulatory requirements and controls

Understand regulatory requirements and controls

![]() Understand code of conduct and ethics in a healthcare information environment

Understand code of conduct and ethics in a healthcare information environment

Legal issues that pertain to information security and privacy for healthcare organizations

Under the wide array of legal issues, healthcare organizations face several challenges around information security and privacy. In addition to there being high-level governance frameworks, many of the specific security and privacy requirements impact the operations of healthcare organizations. Although all healthcare organization employees have the responsibility for properly safeguarding healthcare information, security, and privacy, professionals are at the forefront of compliance with legal and regulatory requirements associated with healthcare delivery.

Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 (HIPAA)

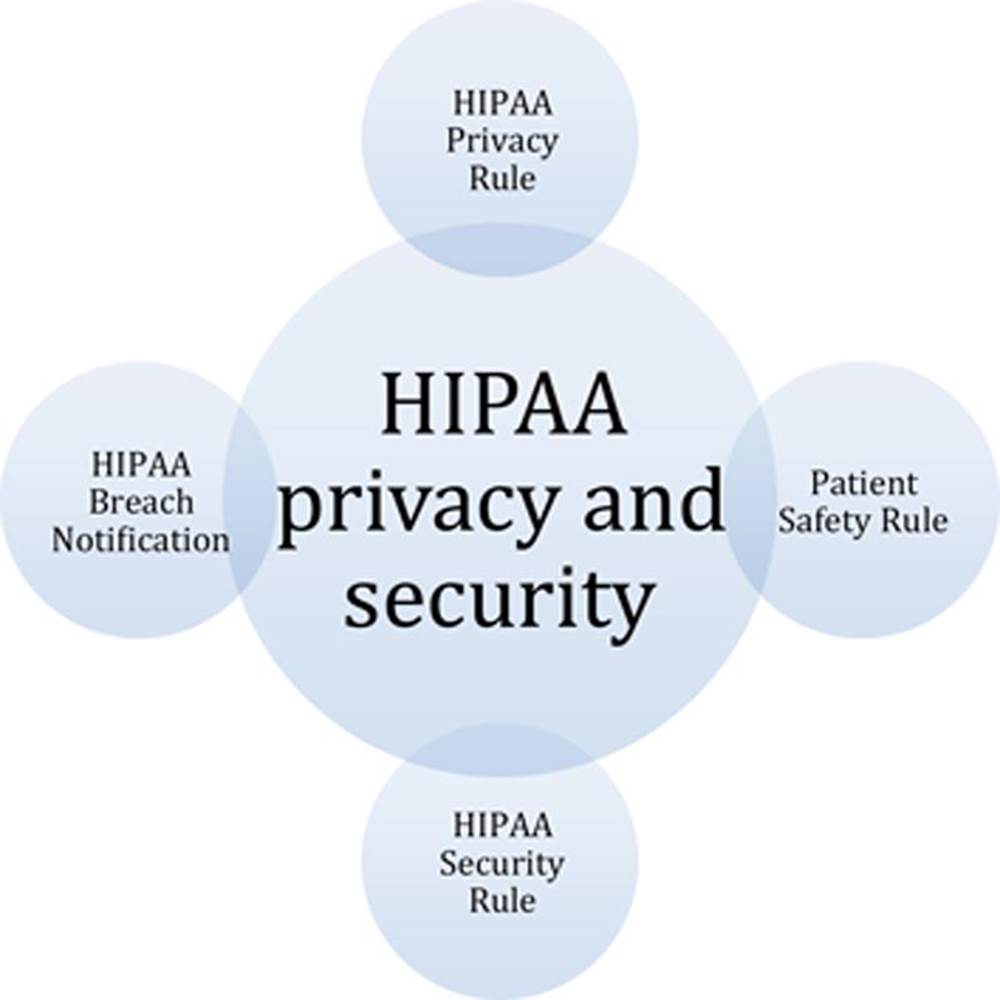

In the United States, one of the most important healthcare laws is HIPAA. According to the Office for Civil Rights, “The Office for Civil Rights enforces the HIPAA Privacy Rule, which protects the privacy of individually identifiable health information; the HIPAA Security Rule, which sets national standards for the security of electronic protected health information; the HIPAA Breach Notification Rule, which requires covered entities and business associates to provide notification following a breach of unsecured protected health information; and the confidentiality provisions of the Patient Safety Rule, which protect identifiable information being used to analyze patient safety events and improve patient safety.” Although HIPAA contains several legislative mandates, the most relevant section to information security is the Administrative Simplification section. This section includes the standards for privacy, security, and enforcement. Figure 3.1 shows the relationship between the various elements of HIPAA.

FIGURE 3.1 Elements of HIPAA.

Select elements and definitions

As stated earlier, HIPAA has several elements and covers a number of issues that healthcare organizations must comply with. However, for exam preparation purposes we would like to highlight some select elements and definitions from HIPAA. According to the HIPAA, Public Law 104-191 (August 21, 1996), Subtitle F Administrative Simplification, Part C, Section 1171, the term “health information” means any information, whether oral or recorded in any form or medium, that:

1. Is created or received by a health care provider, health plan, public health authority, employer, life insurer, school or university, or health care clearinghouse; and

2. Relates to the past, present, or future physical or mental health or condition of an individual; the provision of health care to an individual; or the past, present, or future payment for the provision of health care to an individual.

Individually identifiable health information is information that is a subset of health information, including demographic information collected from an individual, and:

1. Is created or received by a health care provider, health plan, employer, or health care clearinghouse; and

2. Relates to the past, present, or future physical or mental health or condition of an individual; the provision of health care to an individual; or the past, present, or future payment for the provision of health care to an individual; and:

a. That identifies the individual; or

b. With respect to which there is a reasonable basis to believe the information can be used to identify the individual.

Additionally, protected health information is defined by 45 CFR 160.103, and, as defined, is referenced in Section 13400 of Subtitle D (“Privacy”) of the Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health Act (HITECH Act).

“Protected health information means individually identifiable health information [defined above]:

(1) Except as provided in paragraph

(2) of this definition, that is:

(i) Transmitted by electronic media;

(ii) Maintained in electronic media; or

(iii) Transmitted or maintained in any other form or medium.

(2) Protected health information excludes individually identifiable health information in:

(i) Education records covered by the Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act, as amended, 20 U.S.C. 1232g;

(ii) Records described at 20 U.S.C. 1232g(a)(4)(B)(iv); and

(iii) Employment records held by a covered entity in its role as employer.”

The American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (ARRA) of 2009

The ARRA of 2009 was enacted to provide stimulus and recovery mechanisms in response to the great recession. Although there are many elements to ARRA, most of which are outside the scope of this book, we focus our discussions on select healthcare domains, specifically the HITECH Act and amendments to HIPAA.

The most significant changes to HIPAA now include:

![]() The final Breach Notification Rule

The final Breach Notification Rule

![]() Updates to business associate responsibilities

Updates to business associate responsibilities

![]() Expansion of the penalty consequences

Expansion of the penalty consequences

![]() Investigative authority for potential violations to the Attorney General of each state

Investigative authority for potential violations to the Attorney General of each state

With these changes to HIPAA, healthcare organizations were required to expand and enforce their own privacy and security structures as well as expand the controls to their business relationships and partners with whom they share healthcare information.

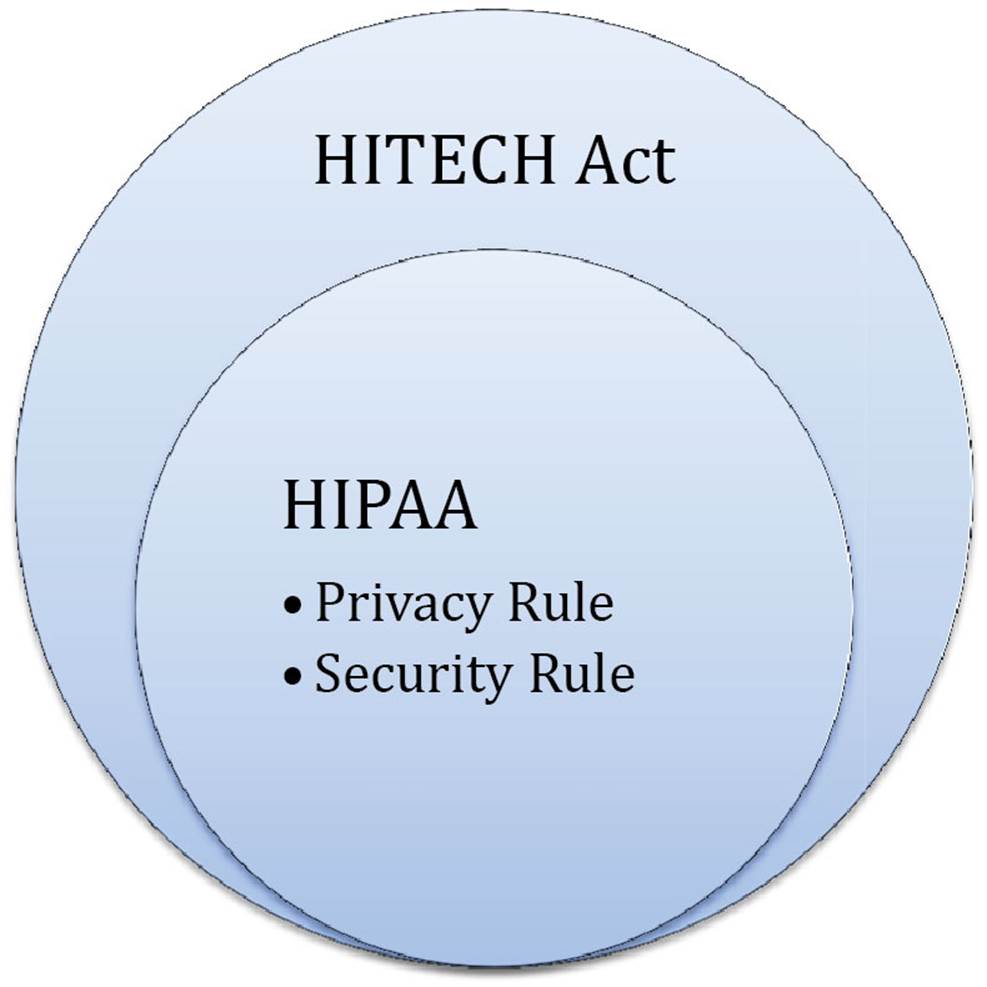

According to the Office for Civil Rights, “The Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health (HITECH) Act, enacted as part of the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009, was signed into law on February 17, 2009, to promote the adoption and meaningful use of health information technology. Subtitle D of the HITECH Act addresses the privacy and security concerns associated with the electronic transmission of health information, in part, through several provisions that strengthen the civil and criminal enforcement of the HIPAA rules.” Figure 3.2 demonstrates the relationship between HITECH Act and HIPAA privacy and security rules. Specifically, they work together to ensure privacy and security concerns are properly addressed as healthcare organizations adopt and extend the meaningful use of health information technology (IT).

FIGURE 3.2 Relationship between HITECH and HIPAA.

International standards

When looking outside of U.S. boundaries, many international healthcare organizations face similar legal and regulatory challenges. Several countries are developing or adhering to regulations that require the protection of personally identifiable information used by healthcare organizations. Some of the more common laws and regulations include:

![]() Canada’s Personal Information Protection and Electronic Documents Act (PIPEDA) – Sets out ground rules for how private sector organizations may collect, use, or disclose personal information in the course of commercial activities.

Canada’s Personal Information Protection and Electronic Documents Act (PIPEDA) – Sets out ground rules for how private sector organizations may collect, use, or disclose personal information in the course of commercial activities.

![]() European Commission Data Protection Legislation – Various legislation, documents, and guidance on the protection of personal data within the European Union.

European Commission Data Protection Legislation – Various legislation, documents, and guidance on the protection of personal data within the European Union.

![]() UK Data Protection Act 1998 – Controls how organizations, businesses, or the government uses your personal information.

UK Data Protection Act 1998 – Controls how organizations, businesses, or the government uses your personal information.

A culture of privacy and security

It is important to remember that employees take their cues from the organization’s senior leadership. When senior leaders place importance on proactive security and privacy programs, healthcare organizations can properly safeguard the personal health information (PHI) entrusted to them by the patients they serve. This “tone at the top” not only enables the right attitude when delivering patient care services but also ensures that privacy and security professionals have the resources they need. Although it is important to remember that every employee at a healthcare organization is responsible for safeguarding PHI, privacy and security professionals are charged with the protection of PHI on a daily basis. Although there can be subtle differences between the specific roles of privacy and security professionals, we think it is best to focus on the intent and key principles needed to support effective privacy and security programs and leave organizational structure and job roles to be managed by individual healthcare organizations. Both privacy and security efforts should be thoroughly documented in policies, procedures, and standards within the organization. Additionally, those efforts need to be supported by the organization’s senior leadership.

Organizational-level privacy and security requirements

Many organizations find it is best to focus on the successful implementation and management of comprehensive privacy and security programs based on industry best practices. A majority of the time, doing so complies with most specific regulatory or legal requirements and provides greater program efficiency as opposed to chasing various fragmented regulatory requirements as disparate compliance activities. Some of the key privacy and security principles organizations should focus on include the following:

![]() The PHI must be collected by an organization for a specific purpose and used only for that purpose.

The PHI must be collected by an organization for a specific purpose and used only for that purpose.

![]() PHI must be kept isolated from any persons who are not authorized by the organization or the original data owner.

PHI must be kept isolated from any persons who are not authorized by the organization or the original data owner.

![]() The information must be deleted at an appropriate time (i.e., when no longer needed for its intended purpose).

The information must be deleted at an appropriate time (i.e., when no longer needed for its intended purpose).

Data breach regulations

Unfortunately, even with all of a healthcare organization’s privacy and security controls in place, there is a good chance a data breach will occur. Organizations are obligated to take certain steps when a data breach has been believed to occur. Understanding the definition of a data breach and the required steps after a breach is critical for healthcare organizations. This knowledge and understanding enables compliance with various regulatory and legal requirements. According to the U.S. Health and Human Services Office for Civil Rights, “A breach is, generally, an impermissible use or disclosure under the Privacy Rule that compromises the security or privacy of the protected health information. An impermissible use or disclosure of protected health information is presumed to be a breach unless the covered entity or business associate, as applicable, demonstrates that there is a low probability that the protected health information has been compromised based on a risk assessment of at least the following factors:

1. The nature and extent of the protected health information involved, including the types of identifiers and the likelihood of re-identification;

2. The unauthorized person who used the protected health information or to whom the disclosure was made;

3. Whether the protected health information was actually acquired or viewed; and

4. The extent to which the risk to the protected health information has been mitigated.”

In addition to understanding how data breaches are defined, healthcare organizations must also understand their reporting responsibilities. Specifically, the Office for Civil Rights declares that “The HIPAA Breach Notification Rule, 45 CFR §§ 164.400-414, requires HIPAA covered entities and their business associates to provide notification following a breach of unsecured protected health information. Similar breach notification provisions implemented and enforced by the Federal Trade Commission apply to vendors of personal health records and their third party service providers, pursuant to section 13407 of the HITECH Act.” From an operational perspective, this means that organizations must have policies and procedures in place to detect and respond to data breaches and have the capabilities for proper notification in accordance with industry best practices and in adherence with legal and regulatory requirements.

Penalties and fees

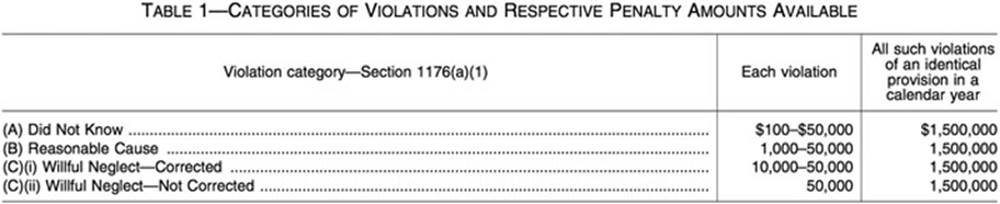

Healthcare organizations should not only focus on proactive measures to avoid privacy and security problems but also need to understand the consequences of not having effective privacy and security programs and noncompliance with regulatory requirements. Many legal and regulatory requirements have specific penalties and fines for noncompliance. One stringent example is ARRA of 2009, which included updates to HIPAA and increased the penalties for unauthorized disclosure of PHI. Fines can be levied up to $1.5 million per annum. Figure 3.3 from the Federal Register (Vol. 74, No. 209, Friday, October 30, 2009) depicts the specific penalties.

FIGURE 3.3 HIPAA violation and corresponding penalties.

45 CFR 164.514: HIPAA Privacy Rule (the de-identification standard and its two implementation specifications)

As part of understanding and complying with the HIPAA Privacy Rule, careful consideration must be given to data de-identification and the associated implementation specifications. The focus of this chapter is on the healthcare regulatory environment and at this point in the exam preparation process, it is only important to note that there are 18 personal data identifiers and the standard requires that data be de-identified following the 2-implementation specifications. Additional, specific information on the 18 personal data identifiers and the implementation standards are discussed in Chapter 4.

In common practice, the list of the 18 personal data identifiers helps organizations understand that if a document or set of information contains any of these characteristics or combinations of personal data identifiers, about an individual or a number of individuals, then that set of information should be considered PHI and protected accordingly.

Information flow mapping

Given the inordinate and ever-growing amount of data most healthcare organizations have in their possession, managing data and information flows is of the utmost importance. This often proves to be challenging for many healthcare organizations given the volume and types of data within their environment. Specifically, organizations need to determine what data are considered PHI and where they are located on their infrastructure, which commonly includes servers, storage, and endpoint devices. Unfortunately, many data breaches occur when organizations do not properly identify the entire range of PHI that flows through their environment and therefore cannot implement the appropriate safeguards. Ignorance of where PHI is located within an organization’sboundaries does not exonerate the organization from legal and regulatory compliance. This is why information flow mapping is critical to healthcare organizations protecting PHI in their possession.

Monitoring PHI information flows

After a healthcare organization identifies PHI and implements appropriate safeguards, they must also continuously monitor the information flow and access to the information, and report any breaches if the information is inappropriately accessed or otherwise compromised. For many organizations this means the need to institute information security practices and associated technology that can identify and protect the stored PHI, control access to the PHI, and manage the information flow inside and outside the organization’s physical, logical, and legal boundaries.

Jurisdictional implications

In addition to organizations needing to understand the relationship that PHI has within their physical, logical, and legal boundaries, they must also be aware of any jurisdictional issues. Healthcare organizations in today’s digitally connected world have many external, but interconnected business relationships associated with their healthcare delivery services. This requires healthcare organizations to be aware of any data sharing issues, particularly when transacting with other organizations across local, state, national, or international boundaries. Understanding the jurisdictional implications of sharing data from one organization to another ahead of time is essential so that each organization can understand any liabilities and responsibilities involved in the exchange of healthcare information. However, understanding is just the first step, and healthcare entities must implement the appropriate privacy and safeguards.

Data Use and Reciprocal Support Agreement (DURSA)

The DURSA is a common data sharing agreement that enables healthcare organizations to share information. Prior to the development of DURSA, many organizations struggled with sharing information due to the lack of uniform standards across various state and local healthcare privacy and security laws. The Office of the National Coordinator for Health IT developed the DURSA for organizations participating in electronic health information exchanges (HIEs). It was built upon the legal requirements of the participants and seeks to provide a framework that insures protection for health information during exchanges. The Agreement reflects consensus among the state-level, federal-level, and private entities regarding the following issues:

![]() Multiparty agreement

Multiparty agreement

![]() Participants actively engaged in HIE

Participants actively engaged in HIE

![]() Privacy and security obligations

Privacy and security obligations

![]() Requests for information based on a permitted purpose

Requests for information based on a permitted purpose

![]() Duty to respond

Duty to respond

![]() Future use of data received from another participant

Future use of data received from another participant

![]() Respective duties of submitting and receiving participants

Respective duties of submitting and receiving participants

![]() Autonomy principle for access

Autonomy principle for access

![]() Use of authorizations to support requests for data

Use of authorizations to support requests for data

![]() Participant breach notification

Participant breach notification

![]() Mandatory nonbinding dispute resolution

Mandatory nonbinding dispute resolution

![]() Allocation of liability risk

Allocation of liability risk

Data subjects

The specific data elements of human subjects commonly contained in PHI entrusted to healthcare organizations are extremely valuable. These data have tremendous value on the black market and are therefore highly valued and targeted by cybercriminals. With the ubiquitous nature of today’s PHI being made available electronically, organizations find themselves as primary targets and face an ever-increasing amount of cyber attacks.

Data ownership

Although a patient is the ultimate owner of their personal healthcare information, there are many individuals (e.g., controllers, custodians, processors) within a healthcare organization who collectively have responsibilities for protecting PHI and act on the owner’s behalf. Any sharing of PHI that is in possession of a healthcare organization must be done with appropriate consent. Additionally, even if the patient is not currently receiving treatment or is otherwise a current patient of the provider, the healthcare organization is still responsible for safeguarding the PHI.

Legislative and regulatory updates

Since the legal and regulatory environments are constantly changing with various updates to address constant changes in society, technology, and healthcare, organizations must stay abreast of changes and revise their policies, procedures, and operations to remain compliant and in good standing. It is important to know that organizations are also responsible for providing training and awareness on said changes to ensure that all of the employees are compliant with the most up-to-date legal and regulatory requirements when delivering healthcare.

Treaties

With an increase in globalization, countries are often compelled by businesses and healthcare organizations to find ways to conduct business despite country-specific legal and regulatory requirements. To accomplish such undertakings, countries collaborate on international agreements to address any of the differences in how PHI is used and protected. Additionally, there are many country-specific requirements, and sometimes organizations will create legal agreements that exclusively govern the partnerships and exchanges between two specific organizations. Therefore, it is best for each organization to be aware of their specific requirements and create agreements accordingly. However, there are other instances where healthcare organizations need to be aware of broader privacy and security agreements, such as Safe Harbor.

International Safe Harbor Principles

The U.S.–EU Safe Harbor is an agreed-upon process that enables U.S. companies to comply with the EU Directive 95/46/EC (the protection of personal data). Organizations operating in the European Union cannot send personal data outside of the European Economic Area (EEA) unless the organizations outside of the EEA are compliant with the Safe Harbor Privacy Principles. The seven privacy principles include:

![]() Notice – Organizations must notify individuals about the purposes for the data collection.

Notice – Organizations must notify individuals about the purposes for the data collection.

![]() Choice – Organizations must give individuals the opportunity to choose (i.e., opt out and opt in – an affirmative choice is required when dealing with sensitive data) if their information is to be shared with a third party or used for purposes other than it was originally collected for.

Choice – Organizations must give individuals the opportunity to choose (i.e., opt out and opt in – an affirmative choice is required when dealing with sensitive data) if their information is to be shared with a third party or used for purposes other than it was originally collected for.

![]() Onward transfer (transfers to third parties) – Prior to transfer organizations must follow the principles of notice and choice.

Onward transfer (transfers to third parties) – Prior to transfer organizations must follow the principles of notice and choice.

![]() Access – Individuals must have access to personal information about them that an organization holds and be able to correct, amend, or delete that information where it is inaccurate.

Access – Individuals must have access to personal information about them that an organization holds and be able to correct, amend, or delete that information where it is inaccurate.

![]() Security – Organizations must take reasonable precautions to protect personal information from loss, misuse, and unauthorized access, disclosure, alteration, and destruction.

Security – Organizations must take reasonable precautions to protect personal information from loss, misuse, and unauthorized access, disclosure, alteration, and destruction.

![]() Data integrity – An organization should take reasonable steps to ensure that data are reliable for their intended use, accurate, complete, and current.

Data integrity – An organization should take reasonable steps to ensure that data are reliable for their intended use, accurate, complete, and current.

![]() Enforcement – There must be (a) readily available and affordable independent recourse mechanisms so that each individual’s complaints and disputes can be investigated and resolved and damages awarded where the applicable law or private sector initiatives so provide; (b) procedures for verifying that the commitments companies make to adhere to the Safe Harbor principles have been implemented; and (c) obligations to remedy problems arising out of a failure to comply with the principles.

Enforcement – There must be (a) readily available and affordable independent recourse mechanisms so that each individual’s complaints and disputes can be investigated and resolved and damages awarded where the applicable law or private sector initiatives so provide; (b) procedures for verifying that the commitments companies make to adhere to the Safe Harbor principles have been implemented; and (c) obligations to remedy problems arising out of a failure to comply with the principles.

Industry-specific laws

There are several industry-specific laws and regulations that may also be applicable to a healthcare organization; many are out of scope for this discussion and preparation for the HCISPP preparation. However, the following section will review some of the more common compliance requirements facing today’s organizations. Having a basic familiarity of similar legal and privacy requirements facing most organizations is beneficial to healthcare organizations, particularly when considering their scope of compliance and ensuring safeguards can be applied to other compliance requirements. However, we recommend that each organization take the time to consider any additional laws at the local, state, or federal level that may be relevant to an organization’s specific business and operations models. Although not exhaustive, the following list highlights some of the more common legal and regulatory requirements facing today’s healthcare organizations beyond healthcare-specific regulatory requirements:

![]() Occupational Safety and Health Act of 1970 (OSH Act) – Under the OSH Act, employers are responsible for providing a safe and healthful workplace.

Occupational Safety and Health Act of 1970 (OSH Act) – Under the OSH Act, employers are responsible for providing a safe and healthful workplace.

![]() Payment Card Industry Data Security Standards (PCI DSS) – Provides an actionable framework for developing a robust payment card data security process, including prevention, detection, and appropriate reaction to security incidents.

Payment Card Industry Data Security Standards (PCI DSS) – Provides an actionable framework for developing a robust payment card data security process, including prevention, detection, and appropriate reaction to security incidents.

![]() Sarbanes–Oxley Act (SOX) – The Act mandated a number of reforms to enhance corporate responsibility, enhance financial disclosures, and combat corporate and accounting fraud, and created the Public Company Accounting Oversight Board.

Sarbanes–Oxley Act (SOX) – The Act mandated a number of reforms to enhance corporate responsibility, enhance financial disclosures, and combat corporate and accounting fraud, and created the Public Company Accounting Oversight Board.

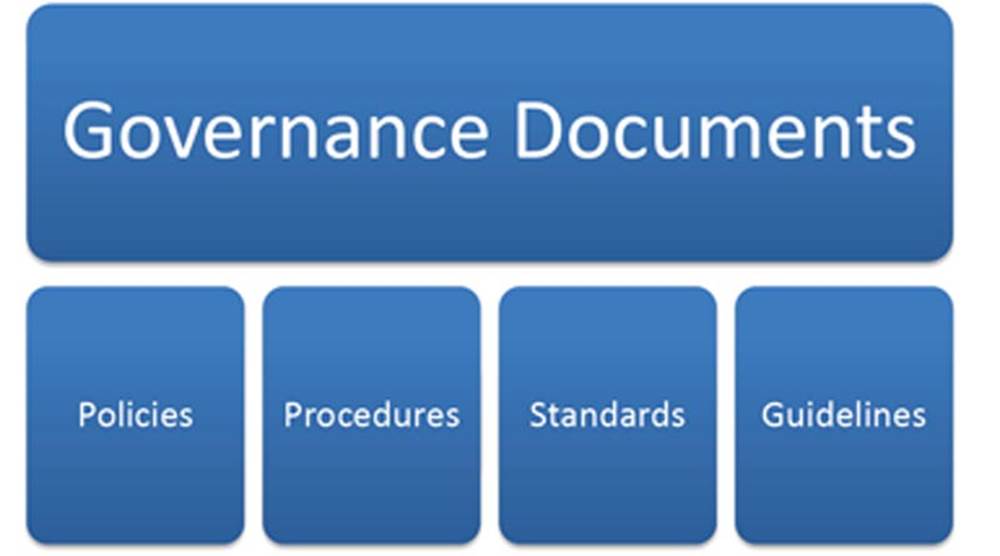

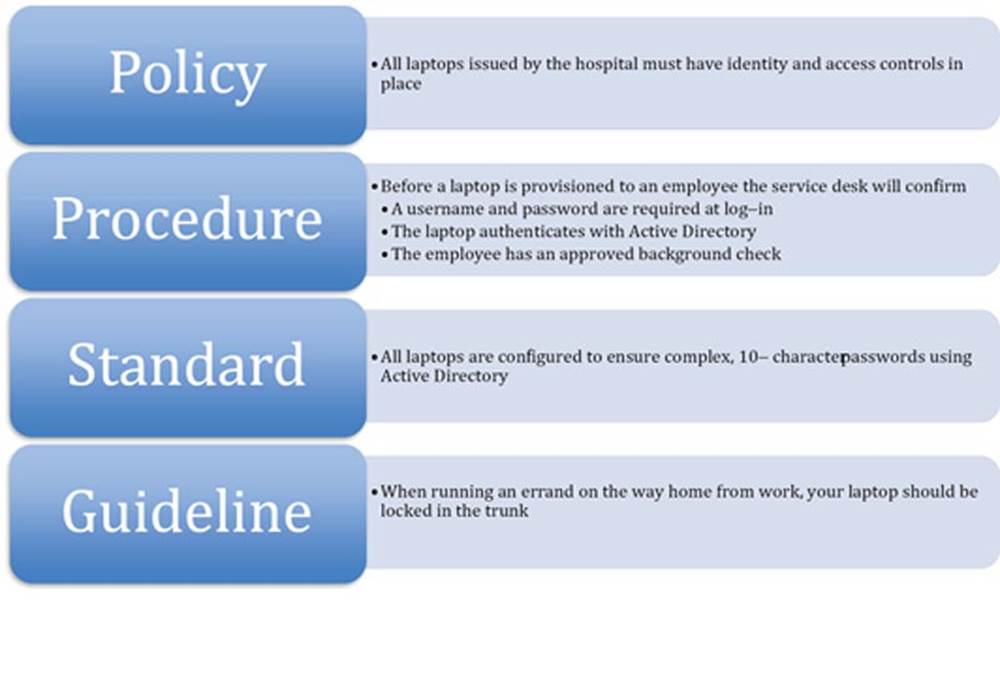

Policies, procedures, standards, and guidelines

At the surface, policies, procedures, standards, and guidelines sound synonymous. However, there are distinct differences and organizations must understand these subtleties as well as manage the relationship among these governance tools in order to ensure a successful privacy and security program within a healthcare organization. In Figure 3.4 is given the relationship between each distinct governance document (e.g., policy, procedure).

FIGURE 3.4 Relationship between policies, procedures, standards, and guidelines.

Now that we understand the relationship between policies, standards, and guidelines and how they support an organization’s privacy and security program, we can examine the specifics of each.

Policies

Policies are high-level formal documents that briefly state the organization’s perspective on a particular topic. Typically these are approved by senior management and help enforce the “tone at the top” for the organization. Since they are written at a high level, they focus on organizational objectives, rather than specific guidance on how to achieve said objectives.

Procedures

Procedures are the detailed sequential steps that are documented and inform the healthcare organization’s employees on how to perform specific actions. Since policies are written at a high level and only state what the organization is trying to accomplish, procedures are needed to tell employees how to specifically accomplish the organizational objectives.

Standards

A standard is a set of specifications that must be followed by the healthcare organization’s employees and typically addresses a system or technical configuration. For example, the organization might have a standard for all employee laptops using the Microsoft Windows operating system. This would specify how the operating system and laptop are configured throughout the entire organization. Standards enable organizations to have consistency. Having organizational consistency supports policies and ensures that privacy and security objectives are achieved uniformly within the organization. Standards are not optional and are required throughout the organization.

Guidelines

Guidelines are documented recommendations or suggestions that offer topic-specific guidance based on industry best practices. Most healthcare organizations provide guidelines to employees to help them make reasonable choices and guide them toward decisions and producing outcomes that align with industry best practices.

A Practical Example

The following scenario can be used to exemplify the relationship between a policy, procedure, standard, and guideline. The senior leadership team at a healthcare organization is concerned about restricting access to PHI and preventing unauthorized users from accessing PHI from the organization’s laptops. The senior leadership team recognizes that they need to provide information on ensuring this objective is met and know that many end users will require specific information on how to comply with the objective. Also, they recognize the controls will be more successful and easier to manage when deployed consistently across the organization. Figure 3.5 demonstrates how the earlier scenario flows across an organization’s policies, procedures, standards, and guidelines.

FIGURE 3.5 A practical example of a policy, procedure, standard, and guideline.

Common security and privacy compliance frameworks

There are a number of security and privacy compliance frameworks available to healthcare organizations that can be used to ensure PHI is properly safeguarded and organizations are compliant with privacy and security, legal, and regulatory requirements. Each organization must decide which framework best suits their specific business and regulatory requirements, but the following is a list and brief description of the most common security and privacy compliance frameworks available to healthcare organizations. Since there are advantages and disadvantages between the various frameworks, we recommend taking a “best-breed” or hybrid approach and selecting the combination of frameworks that best suits your healthcare organization’s specific needs.

ISO

The International Standards Organization (ISO) is recognized across the world and has over 30 standards related to information security best practices and audit. In addition to being a comprehensive privacy and security framework, healthcare organizations conducting business internationally often select this framework. Healthcare organizations either are required or find it to be a well-respected common ground by their international partners.

National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST)

Similar to the ISO, the NIST provides a comprehensive list of standards. The most significant difference between ISO and NIST is that ISO targets the international community, while NIST is U.S. centric. The NIST Special Publication (SP) 800 series are most relevant to privacy and security. While focused on the federal government, they are free to use and can be applied to the private sector. One of the most useful SPs for healthcare organizations is SP 800-66. SP 800-66, An Introductory Resource Guide for Implementing the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) Security Rule, is an invaluable resource for healthcare organizations concerned with the HIPAA Security Rule.

The remainder of the SPs offer suite of comprehensive privacy and security-related guidance. The NIST SPs can be used individually to address specific technology and security issues, but are also designed to work in conjunction (many of the documents reference other documents) so that an organization can accomplish all of its privacy and security goals within a single framework. Although the range of coverage is broad reaching, many healthcare organizations will benefit from the more commonly used documents that address areas such as encryption, security controls, risk management, and awareness and training.

NIST Interagency Reports (IRs)

Another important resource for healthcare organizations that is provided by NIST is the NIST IRs. The NIST IRs are research reports that provide detailed technical information on a specific topic. Healthcare organizations involved in HIEs should review the IR on the secure exchange of health information:

• NISTIR 7497 – Security Architecture Design Process for Health Information Exchanges (HIEs)

Common Criteria

Another widely accepted framework is the Common Criteria. According to the official Common Criteria Arrangement, “The purpose of this Arrangement is to advance those objectives by bringing about a situation in which IT products and protection profiles which earn a Common Criteria certificate can be procured or used without the need for further evaluation.” They also state that the participants in the arrangement share the following objectives:

1. To ensure that evaluations of IT products and protection profiles are performed to high and consistent standards and are seen to contribute significantly to confidence in the security of those products and profiles;

2. To improve the availability of evaluated, security-enhanced IT products and protection profiles;

3. To eliminate the burden of duplicating evaluations of IT products and protection profiles;

4. To continuously improve the efficiency and cost-effectiveness of the evaluation and certification/validation process for IT products and protection profiles.

It is important to note that the Common Criteria is formally known as Common Criteria for Information Technology Security Evaluation (CC). It works with the Common Methodology for Information Technology Security Evaluation (CEM). When organizations adhere to the CC and CEM, they are well positioned to work with another organization under an internationally recognized framework. Specifically, the Common Criteria Recognition Arrangement (CCRA) manages this partnership and framework. The CCRA provides the technical basis for an international agreement among member countries. The standards and the operating methodology are based on the agreement among participating members. It is also important to note that the Common Criteria includes three distinct sets of documentation including the general model, the security functional requirements, and the security assurance requirements. This is further supported by the CEM, which describes the activities performed by an evaluator assessing the implementation of the functional and assurance requirements.

Common criteria–certified product categories

The Common Criteria certifies products under the following categories, to assist participating organizations in their selection process:

![]() Access control devices and systems

Access control devices and systems

![]() Biometric systems and devices

Biometric systems and devices

![]() Boundary protection devices and systems

Boundary protection devices and systems

![]() Data protection

Data protection

![]() Databases

Databases

![]() Detection devices and systems

Detection devices and systems

![]() ID cards, smart cards, and smart card–related devices and systems

ID cards, smart cards, and smart card–related devices and systems

![]() Key management systems

Key management systems

![]() Multifunction devices

Multifunction devices

![]() Network and network-related devices and systems

Network and network-related devices and systems

![]() Operating systems

Operating systems

![]() Products for digital signatures

Products for digital signatures

![]() Trusted computing

Trusted computing

The Information Governance (IG) Toolkit

The IG Toolkit is an online self-assessment tool that enables the National Health Service (NHS) organizations and partners in the United Kingdom to comply with the Department of Health Information Governance policies and standards.

Although there are different standards for different types of organizations, the IG Toolkit assesses all organizations against the following governance requirements:

![]() Management structures and responsibilities (e.g., assigning responsibility for carrying out the IG assessment, providing staff training)

Management structures and responsibilities (e.g., assigning responsibility for carrying out the IG assessment, providing staff training)

![]() Confidentiality and data protection

Confidentiality and data protection

![]() Information security

Information security

Generally Accepted Privacy Principles (GAPP)

The GAPP is a set of privacy principles that are jointly defined by the American Institute of Certified Public Accountants (AICPA) and the Canadian Institute of Chartered Accountants (CICA). The principles are based on commonly accepted privacy standards for protecting personal information. Further discussion and additional details of GAPP are in Chapter 4.

Health Information Trust Alliance (HITRUST)

According to HITRUST, “The Health Information Trust Alliance (HITRUST) was born out of the belief that information security should be a core pillar of, rather than an obstacle to, the broad adoption of health information systems and exchanges.”

HITRUST bases its program on the Common Security Framework (CSF). The CSF can be used by any and all organizations that create, access, store, or exchange personal health and financial information. One of the benefits of the CSF is that it was designed to align with many existing requirements. HITRUST states, “The CSF is an information security framework that harmonizes the requirements of existing standards and regulations, including federal (HIPAA, HITECH), third party (PCI, COBIT) and government (NIST, FTC).”

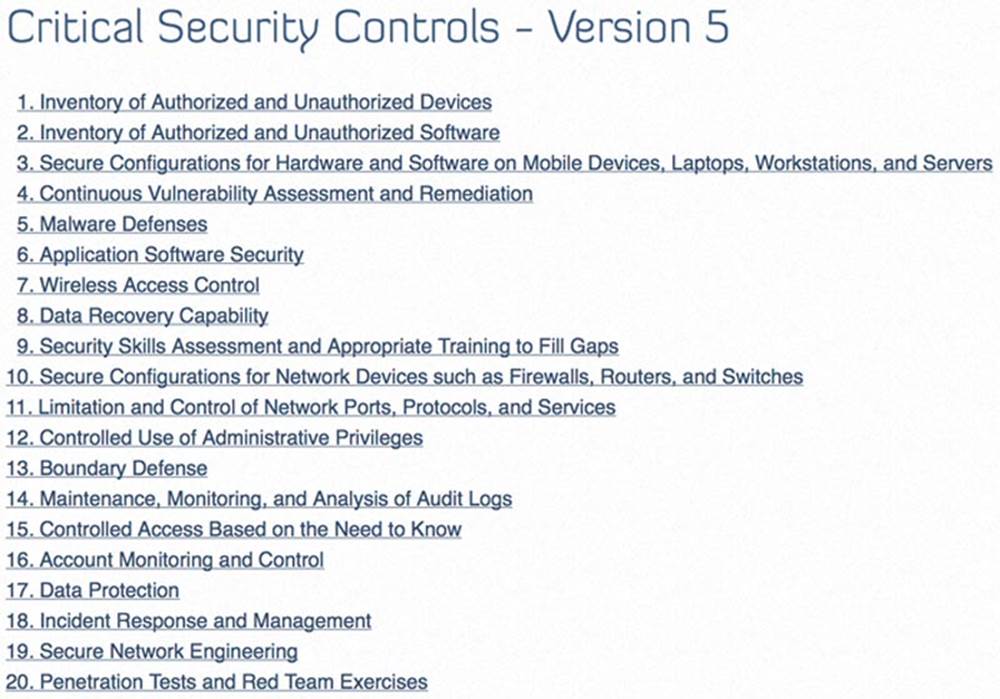

SANS critical security controls

The SANS 20 Critical Security Controls are essentially a subset of the NIST SP 800-53 Controls. They are a selection of the 20 most critical controls that organizations “must have in place.” They are viewed as “must haves” because they are the most critical and broad-reaching controls that, when implemented correctly, provide the most value for organizations with the fewest number of control implementations. We do not advocate limiting your organization’s security control framework to only 20 controls, but agree this is a great starting point, with fundamental security controls, covering a broad area of security risk. Organizations may use the SANS 20 Critical Security Controls under the Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License. In accordance with the license (http://www.sans.org/critical-security-controls/) Figure 3.6 displays the latest version of the SANS 20 Critical Security Controls.

FIGURE 3.6 SANS Critical Security Controls – Version 5.

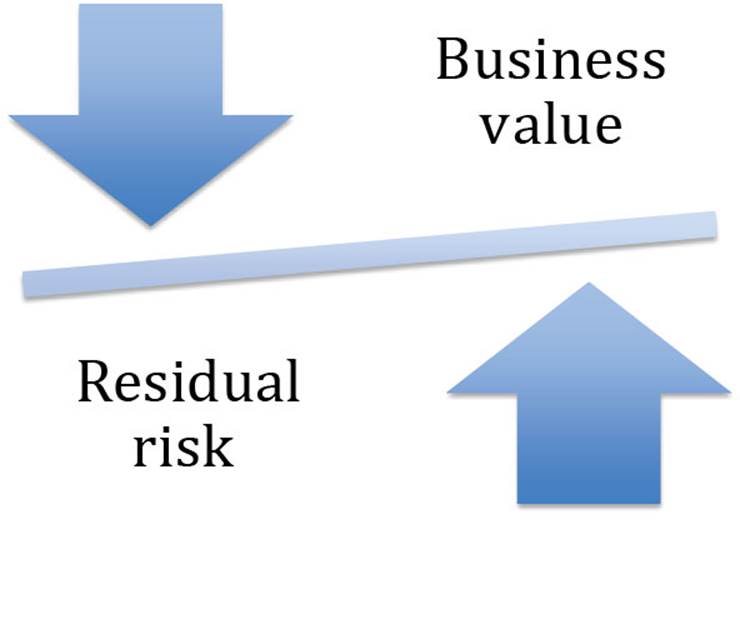

Risk-based decision making

Although Chapter 5 will detail specific risk management methodologies and life cycles for healthcare organizations, a brief discussion on risk-based decision making is warranted in our discussion of the regulatory environment. At a high level, the outcome of risk management activities for organizations is identifying a risk, implementing appropriate controls to reduce the identified risk, and managing any residual risk so that the organizations can achieve their business and organizational-level goals and objectives. Since there is no such thing as zero risk, healthcare organizations must take a risk-based approach and balance the identified risks against the rewards of business and financial objectives when delivering healthcare services. Figure 3.7 demonstrates the cost–benefit perspective organizations must consider when delivering today’s information-based healthcare services.

FIGURE 3.7 Balance of risk versus reward when delivering information-based healthcare.

We are not advocating that healthcare organizations are reckless with PHI when achieving financial and business goals. In fact, we are taking the opposite perspective. The following discussions on compensating controls and managing residual risk will allow organizations to properly safeguard PHI while balancing the business benefits with identified risks when delivering technology-based healthcare services.

Compensating controls

In Chapter 4, we will detail specific types of controls that organizations can use to safeguard PHI. From a high-level perspective a control is implemented by an organization to address an identified vulnerability or risk that could be exploited by a threat. Healthcare organizations should implement a comprehensive set of primary controls to address any risks identified in their governance and risk management process. Fundamentally, there are three categories of controls (administrative, technical, and physical) with three possible implementation types (preventive, detective, and corrective) that can be applied to each category. For example, a healthcare organization can have a series of technical controls that are implemented with an end result of a preventive technical control, a detective technical control, and a corrective technical control. There is no limit on the combination of categories or implementation types a healthcare organization can have, but the organization must have a comprehensive and layered set of controls that addresses any identified risks. To better understand the possible range of combinations, types, and implementations available to healthcare organizations, each control category and implementation type is defined as follows:

![]() Administrative – A senior management–driven control, such as policy.

Administrative – A senior management–driven control, such as policy.

![]() Logical – System software–level control that limits access, such as role-based access controls.

Logical – System software–level control that limits access, such as role-based access controls.

![]() Physical – Provides access control at a physical layer, such as door locks.

Physical – Provides access control at a physical layer, such as door locks.

![]() Preventative – Prevents a threat from exploiting vulnerabilities, such as a firewall.

Preventative – Prevents a threat from exploiting vulnerabilities, such as a firewall.

![]() Detective – Alerts the organization that an unauthorized activity has occurred, such as an intrusion detection system.

Detective – Alerts the organization that an unauthorized activity has occurred, such as an intrusion detection system.

![]() Corrective – Corrects or reduces the harmful activity from further exploiting the vulnerability, such as a patch management tool that fixes identified system issues.

Corrective – Corrects or reduces the harmful activity from further exploiting the vulnerability, such as a patch management tool that fixes identified system issues.

Figure 3.8 displays the relationship between the three control categories (administrative, technical, and physical) and the implementation types (preventive, detective, and corrective) typically included in a set of comprehensive primary controls.

FIGURE 3.8 Relationship between control categories and implementation types.

According to SANS, “Compensating controls are alternate controls designed to accomplish the intent of the original controls as closely as possible, when the originally designed controls can not be used due to limitations of the environment. These are generally required when our activity phase controls are not available or when they fail.” After an organization implements their primary comprehensive control framework, other controls may be needed to address any residual risk, control failures, and gaps. Compensating controls should be implemented by healthcare organizations to address any primary control failures or shortcomings. They should be used to address any residual risk after primary controls have been implemented. Compensating controls can also allow a healthcare organization an additional layer of protection and support a defense-in-depth approach to privacy and security.

Control variance documentation

In a majority of circumstances healthcare organizations should be adhering to the security and privacy controls outlined in their selected framework. However, there are times where it makes sense to deviate from program specifics. Organizations must do so by leveraging a risk-based approach. These types of operational deviations should not be considered lightly or approached haphazardly. Prior to being in an actual situation that requires an operational variance to the privacy and security program, organizations must have a specific process in place that allows them to deviate from the standard program. This must occur in a controlled manner, but still accomplish the overall privacy and security goals. Most organizations will find this is best achieved by having a formal risk management and documentation process. This should be in place and designed to address operational variances, emergencies, and other unplanned events. When organizations properly document action plans and strategies ahead of an actual event, they are better prepared to deal with the situation at hand. Even with a proactive process and documentation, there still may be operational challenges, unintended consequences, and residual risk. However, if the process is comprehensive in nature and deviations are properly documented, organizations will be positioned to successfully deviate from their primary security and privacy programs, while addressing special circumstances or unplanned events. Another benefit of the documentation is that it can be used for a retrospective and organizational lessons learned. Often, during an unplanned event, organizations are consumed by managing the event at a tactical level. After the event, healthcare organizations can take a strategic perspective, and implement any required program changes identified during the retrospective. These changes can be used to enhance the existing privacy and security program.

Residual risk tolerance

As we have already stated there is no such thing as zero risk. Organizations must accept a certain level of residual risk (after implementing a comprehensive set of security controls to address the initial risk that has been identified) when delivering information-driven healthcare services. Since each healthcare organization’s senior leadership team has a different level of risk acceptance, residual risk tolerance will vary greatly among organizations. Therefore, each organization must carefully consider their culture, business model, and the types of healthcare services they deliver. Although the specific business and operating requirements vary significantly among healthcare organizations, there are some common elements that impact the acceptance of residual risk. These typically include cost considerations, the regulatory environment, and technology and resource limitations. Since healthcare organizations constantly face an ever-changing threat landscape, they must continuously review their risk management programs. When doing so, they must also ensure the residual risk they accept is appropriate for the healthcare services they deliver. Finally, it is important that the senior leadership team fully understands and is accountable for the residual risk they have accepted on behalf of the organization and healthcare recipients.

Organizational code of ethics

A healthcare organization that is in possession of PHI has an ethical duty to properly safeguard PHI and associated sensitive data. Healthcare organizations are in a position of trust and the recipients of their services demand the highest ethical standards when entrusting their most personal information to a healthcare organization. Since organizations have access to the vast amounts of PHI, it is important that all employees embrace ethical behavior. Additionally senior managers must lead by example and with an ethical “tone at the top.” An import step toward creating an ethical culture is for healthcare organizations to have policies, procedures, standards, training, and awareness that document and communicate the organization’s Code of Ethics.

(ISC)2 code of ethics

Since the HCISPP is sponsored by the (ISC)2, there is expectation that all members and certificate holders adhere to the highest level of professional standards and ethics. Specifically, the (ISC)2 has a Code of Ethics that must be followed.

Code

The (ISC)2 Code states the following:

“All information systems security professionals who are certified by (ISC)2 recognize that such certification is a privilege that must be both earned and maintained. In support of this principle, all (ISC)2 members are required to commit to fully support this Code of Ethics (the “Code”). (ISC)2 members who intentionally or knowingly violate any provision of the Code will be subject to action by a peer review panel, which may result in the revocation of certification. (ISC)2 members are obligated to follow the ethics complaint procedure upon observing any action by an (ISC)2 member that breaches the Code. Failure to do so may be considered a breach of the Code pursuant to Canon IV.

There are only four mandatory canons in the Code. By necessity, such high-level guidance is not intended to be a substitute for the ethical judgment of the professional.”

Code of Ethics Preamble

(ISC)2 states the following for their Code of Ethics Preamble:

![]() “The safety and welfare of society and the common good, duty to our principals and to each other, requires that we adhere, and be seen to adhere, to the highest ethical standards of behavior.

“The safety and welfare of society and the common good, duty to our principals and to each other, requires that we adhere, and be seen to adhere, to the highest ethical standards of behavior.

![]() Therefore, strict adherence to this Code is a condition of certification.”

Therefore, strict adherence to this Code is a condition of certification.”

Code of Ethics cannons

The (ISC)2 contains the following mandatory canons in the Code:

![]() “Protect society, the common good, necessary public trust and confidence, and the infrastructure.

“Protect society, the common good, necessary public trust and confidence, and the infrastructure.

![]() Act honorably, honestly, justly, responsibly, and legally.

Act honorably, honestly, justly, responsibly, and legally.

![]() Provide diligent and competent service to principals.

Provide diligent and competent service to principals.

![]() Advance and protect the profession.”

Advance and protect the profession.”

Sanctions

(ISC)2 has a formal set of complaint procedures for members to address concerns of potentially unethical behavior of any member or certification holder. The procedures enable a process for reporting observations, while assuring appropriate levels of confidentiality. This includes the protection of identity from the general public of the reporting individual and the individual involved in the questionable behavior or practices. Additionally, the (ISC)2 Board of Directors has appointed an Ethics Committee to hear all ethics complaints and make recommendations to the board. The board has final decision-making authority and the ability to provide disciplinary actions for confirmed ethical violations.

Definitions

|

Term |

Definition |

|

Breach |

An impermissible use or disclosure under the Privacy Rule that compromises the security or privacy of the protected health information |

|

Common Criteria |

An internationally recognized technical evaluation and standards program. It is governed by agreement among member countries, using the Common Criteria Recognition Arrangement (CCRA) |

|

Compensating controls |

The additional controls that can be implemented to address any primary control failures, shortcomings, or residual risk |

|

Data controller |

The senior person in charge of managing the data systems used in capturing, storing, or analyzing the PHI of patients under care of the organization. They have the responsibility for authorizing access of internal and external workforce members to the data system and its included PHI |

|

Data custodian |

The staff responsible for the maintenance and integrity of the data system – software and hardware – that houses and processes data containing PHI. This will include keeping the systems updated, backing up stored data, and maintaining and monitoring network activity for potential vulnerabilities |

|

Data owner(s) |

Two types: 1. The person to whom the actual data pertain, i.e., the patient receiving treatment for which the record is being created. This is the individual who has the final determination for how the data are used and by whom the data can be used or disclosed 2. The healthcare organization that provides the treatment services for the patient and captures information during treatment services has an ownership of the health record for the legally specified time period after the treatment has ended |

|

Data processors |

Staff who are involved in implementing the software systems that support health information processing on behalf of the data controller |

|

Guidelines |

Provide suggestions for organizational desired outcomes that align with industry best practices |

|

Health information |

The data collected about a specific person potentially across a number of treatment services from a number of healthcare organizations |

|

Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 (HIPAA) |

HIPAA is the federal Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996. The primary goal of the law is to make it easier for people to keep health insurance, protect the confidentiality and security of healthcare information, and help the healthcare industry control administrative costs |

|

Health record |

The collection of health information based on treatment services provided by a healthcare organization on behalf of a patient receiving the services at that organization |

|

IG Toolkit |

A set of self-assessment steps to enable UK healthcare organizations to comply with the Department of Health Information Governance policies and standards |

|

ISO |

The International Standards Organization (ISO) is recognized across the world and has over 30 standards related to information security best practices and audit |

|

NIST |

National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) addresses the measurement infrastructure within science and technology efforts for the U.S. federal government |

|

Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) |

A unit of the U.S. Department of Labor and addresses safety and protection of workers in organizations that involve hazards and hazardous wastes as potential sources of injuries and health-related problems |

|

Personally identifiable information (PII) |

Any information that allows positive identification of an individual, usually as a combination of several characteristics |

|

Personal health information (PHI) |

The PII involved with the healthcare and treatment of an individual |

|

Policies |

The high-level formal documents that briefly state the organization’s perspective and are driven by senior management to set a “tone at the top” for the organization |

|

Primary control |

The initial set of controls implemented by an organization to protect organizational vulnerabilities from being exploited by threats |

|

Procedures |

The detailed sequential steps that are documented and inform the healthcare organization’s employees on how to perform specific actions |

|

Standards |

Are consistent sets of detailed specifications followed throughout the entire healthcare organization and typically address a system or technical configuration |

Practice Exam

1. ARRA is an acronym for:

a. American Recovery and Reinvestment Act

b. Availability, Resilience, and Readiness Act

c. Applicable Regulations and Requirements Act

d. American Accessibility and Readiness Act

2. HITECH Act is an acronym for:

a. Health Information Technology for Equality and Child Health Act

b. Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health Act

c. Health Information Transfer for Emergency and Clinical Health Act

d. Health Information Technology for Education and Clinical Health Act

3. When U.S. healthcare organizations conduct business internationally, they do not need to be concerned with:

a. HITECH Act

b. UK Data Protection Act

c. PIPEDA

d. Safe Harbor

4. Safe Harbor is based on:

a. HITECH Act and HIPAA

b. Seven privacy principles

c. EU Directive 95/46/EC

d. Both b and c

5. DURSA is an acronym for:

a. Data Use and Reciprocal Support Agreement

b. Data Use and Regulatory Systems Act

c. Data Use and Reciprocal Support Act

d. Data Use and Regulatory Systems Agreement

6. Which of the following is not a principle of Safe Harbor?

a. Access

b. Enforcement

c. Encryption

d. Onward transfer

7. Additional regulatory requirements healthcare organizations are likely to face include:

a. OSH Act

b. PCI–DSS

c. GLBA

d. Both a and b

8. A policy:

a. Does not apply to covered entities

b. Details the sequential steps for healthcare employees to follow

c. Is synonymous with a procedure

d. Is a high-level formal document approved by senior management

9. A procedure:

a. Is a suggestion intended to streamline a healthcare process

b. Details the sequential steps for healthcare employees to follow

c. Is synonymous with a guideline

d. Is a high-level formal document approved by senior management

10. ISO:

a. Is the International Standards Organization

b. Offers over 30 standards related to information security best practices

c. Provides U.S.-approved healthcare security best practices

d. Both a and b

11. NIST:

a. Can only be used by the U.S. government

b. Does not apply to covered entities

c. Can only be used for Safe Harbor compliance

d. None of the above

12. NISTIR 7497:

a. Must be followed according to DURSA

b. Provides required HIPAA security controls for covered entities

c. Is the guide for implementing the HIPAA Security Rule

d. Is Security Architecture Design Process for Health Information Exchanges

13. Common Criteria:

a. Certifies IT products

b. Is a widely accepted framework

c. Is managed under the CCRA

d. All of the above

14. The IG Toolkit:

a. Is an online self-assessment tool

b. Allows organizations in the United Kingdom to comply with DHIG policies and standards

c. Can be used by all types and sizes of organizations

d. All of the above

15. The IG Toolkit assesses organizations against the following governance requirements:

a. Management structures and responsibilities

b. Confidentiality and data protection

c. Information security

d. All of the above

16. GAAP is the acronym for:

a. Globally Accepted Privacy Principles

b. Generally Accepted Privacy Principles

c. Globally Accepted Privacy Practices

d. Generally Accepted Privacy Practices

17. HITRUST:

a. Is only recognized in the United Kingdom

b. Cannot be used with other security frameworks

c. Is required under HITECH Act

d. None of the above

18. SANS 20 Critical Security Controls:

a. Can be used by any organization

b. Supersede NIST SP 800-53 Controls when complying with the HITECH Act

c. Provide the most value with the fewest number of control implementations

d. Both a and b

e. Both a and c

19. Compensating controls:

a. Should not be used by covered entities

b. Should be implemented as part of a comprehensive control framework

c. Are required under HIPAA but not the HITECH Act

d. None of the above

20. The (ISC)2 Code of Ethics:

a. Applies to all members and certificate holders

b. Holds individuals to the highest level of professional standards

c. Has a preamble and four canons

d. All of the above

Practice Exam Answers

1. a

2. b

3. a

4. d

5. a

6. c

7. d

8. d

9. b

10. d

11. d

12. d

13. d

14. d

15. d

16. b

17. d

18. e

19. b

20. d

References

http://www.hhs.gov/ocr/privacy/.

http://www.hhs.gov/ocr/privacy/hipaa/administrative/enforcementrule/hitechenforcementifr.html.

http://www.hhs.gov/ocr/privacy/hipaa/administrative/breachnotificationrule/.

http://ico.org.uk/for_organisations/guidance_index/∼/media/documents/library/Data_Protection/Detailed_specialist_guides/data-controllers-and-data-processors-dp-guidance.pdf.

https://www.priv.gc.ca/leg_c/leg_c_p_e.asp.

http://health.state.tn.us/hipaa/.

http://eurlex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=OJ:L:2009:337:0011:0036:en:PDF.

http://ec.europa.eu/justice/data-protection/index_en.htm.

http://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/1998/29/contents.

http://www.hhs.gov/ocr/privacy/hipaa/administrative/breachnotificationrule/.

http://www.hhs.gov/ocr/privacy/hipaa/administrative/enforcementrule/enfifr.pdf.

http://www.healthit.gov/sites/default/files/dursa-2009-version-for-production-pilots-20091118-1.pdf.

http://www.healthit.gov/sites/default/files/pdf/privacy/privacy-and-security-guide.pdf.

http://www.export.gov/safeharbor/eu/eg_main_018365.asp.

https://www.osha.gov/.

https://www.pcisecuritystandards.org.

http://www.sec.gov/about/laws.shtml#sox2002.

http://www.sec.gov/about/laws/soa2002.pdf.

http://www.sans.org/security-resources/policies/Policy_Primer.pdf.

http://www.iso.org/iso/home.htm.

http://nist.gov/.

http://csrc.nist.gov/publications/nistpubs/800-66-Rev1/SP-800-66-Revision1.pdf.

http://www.hpa.org.uk/web/HPAweb&HPAwebStandard/HPAweb_C/1195733746440.

http://csrc.nist.gov/publications/nistir/ir7497/nistir-7497.pdf.

https://www.commoncriteriaportal.org/.

https://www.igt.hscic.gov.uk/.

http://hitrustalliance.net/.

http://www.sans.edu/research/security-laboratory/article/security-controls.

https://www.isc2.org/ethics/default.aspx.