Building an Information Security Awareness Program: Defending Against Social Engineering and Technical Threats, First Edition (2014)

CHAPTER 6. Why Current Programs Don't Work

Bill Gardner Marshall University, Huntington, WV, USA

Abstract

The lecture as a teaching tool is dead. Current programs don't work because we rely on old models of teaching. People learn in different ways. Some people are visual learners, while others learn better from reading or discussing. We need to move away from canned web-delivered training to interactive, hands-on learning to build more effective security awareness programs.

Keywords

Visual

Audio

Hands-on

Training

Learning

Content delivery

Peer-instruction

The Lecture is Dead as a Teaching Tool

No one likes a lecture, except maybe the person giving it. For the lecturer, the act of giving a lecture is an active exercise. For those attending, the lecture is a passive exercise. Passive learning is shown to be not as effective as active learning when conveying information. In fact, many in higher education say that the lecture, a centuries-old teaching technique, is dead [1].

Research shows that we should do something that universities have been moving toward in the past few years: replacing passive learning with active learning. Active learning depending on how it is implemented has become known at “peer instruction” or “interactive learning.” These techniques make the student responsible for their own learning as well as fostering interaction with other students in interacting with the material to be learned [2].

“Peer instruction” and “interactive learning” take the form of giving students assignments to read or videos to watch and then splitting the students into groups to interact with the material. These interactions involve writing assignments, group discussion, completing assigned tasks as a team, and sometimes a group grade [3]. Sometimes, students play question and answer games based on popular game show formats to engage the material. Points can be awarded in candy or toward a group grade [4].

We know that what we are doing now isn't working because we see examples of breaches that involved exploiting a human in order to gain access to data on an almost daily basis. Users are also showing signs of message malaise. Most users think they will never be tricked into clicking on a link or opening an attachment, because they view themselves as savvy Internet users.

Bruce Schneier, chief security technology officer at BT, wrote an opinion piece for the website Darkreading.com in March 2013 saying that money spent on user awareness training would be better spent on better system design [5]. The post caused a firestorm in information security circles. Some people agree with him but most do not [6,7]. Everybody agrees we have to do something, even Schneier says, “Security is a process, not a product” [8]. If we never inform end users of threats, they will never know about them.

Security awareness has a lot in common with other awareness campaigns. Other awareness campaigns use memorable spokesmen like Smokey the Bear and McGruff the Crime Dog. They also have memorable slogans like “Only you can prevent forest fires,” and “Take a bite out of crime.” In the field of information security awareness, we fail at these two simple goals because we continue to have debates about the effectiveness of security awareness programs.

As Bruce Schneier says, “Security is a process, and not a product” [8]. The process of security is a long hard road that begins with getting management buy-in, drafting and enforcing policies that give the user expectations of what they can and cannot do with the organizations technological resources, building an effective security awareness program, and then measuring the effectiveness of that program using meaningful metrics.

Once metrics are gathered and processed, the cycle begins again with a review of policies, awareness program, and metrics, and changes are made based on the organization's needs.

Doing something is better than doing nothing. The main purpose behind this book is to give people the tools to do something rather than nothing. While there is value in making sure your organization has the latest security products and that your IT staff has proper security training, it is a waste of time and money if you ignore the human factor. Next-generation firewalls, antivirus, intrusion detection systems, intrusion prevention systems, and web application firewalls are all great productions, but these products do not provide protection against an employee making a poor decision about clicking links, opening attachments, and other nontechnical attacks employed by social engineers.

People have different learning styles based upon generational and educational background. The current generation currently entering the workforce learns much differently than those entering the workforce thirty years ago. Some people learn better from reading, others are visual learners, and some learn best from listening.

The Seven Learning Styles

■ Visual (spatial): You prefer using pictures, images, and spatial understanding.

■ Aural (auditory-musical): You prefer using sound and music.

■ Verbal (linguistic): You prefer using words, in both speech and writing.

■ Physical (kinesthetic): You prefer using your body, hands, and sense of touch.

■ Logical (mathematical): You prefer using logic, reasoning, and systems.

■ Social (interpersonal): You prefer to learn in groups or with other people.

■ Solitary (intrapersonal): You prefer to work alone and use self-study.

Why Learning Styles? Understand the basis of learning styles

Your learning styles have more influence than you may realize. Your preferred styles guide the way you learn. They also change the way you internally represent experiences, the way you recall information, and even the words you choose. We explore more of these features in this chapter.

Research shows us that each learning style uses different parts of the brain. By involving more of the brain during learning, we remember more of what we learn. Researchers using brain imaging technologies have been able to find out the key areas of the brain responsible for each learning style.

For example:

■ Visual: The occipital lobes at the back of the brain manage the visual sense. Both the occipital and parietal lobes manage spatial orientation.

■ Aural: The temporal lobes handle aural content. The right temporal lobe is especially important for music.

■ Verbal: The temporal and frontal lobes, especially two specialized areas called the Broca and Wernicke areas (in the left hemisphere of these two lobes).

■ Physical: The cerebellum and the motor cortex (at the back of the frontal lobe) handle much of our physical movement.

■ Logical: The parietal lobes, especially the left side, drive our logical thinking.

■ Social: The frontal and temporal lobes handle much of our social activities. The limbic system (not shown apart from the hippocampus) also influences both the social and solitary styles. The limbic system has a lot to do with emotions, moods, and aggression.

■ Solitary: The frontal and parietal lobes, and the limbic system, are also active with this style [9].

The best strategy is to teach to a mixture of learning styles to see what works best for your organization. Studies have shown that hands-on learning is retained more than other kinds of learning [10,11]. Hands-on learning is active learning. Traditional security awareness programs are composed of slide shows, lectures, and videos. If the slide shows, lectures, and videos are given in person rather than delivered via a website, it is a step toward more active learning since it gives opportunities for the trainer and the participants to interact.

“Active learning” is defined as “… an approach to classroom instruction in which students engage material through talking, writing, reading, reflecting, or questioning—in other words, through being active.” Active learning puts aside the old practices of simply lecturing employees on security best practices. The approach takes security awareness program to the next level through exercises involving talking, reading, writing, reflecting, and questioning [12].

For example, instead of telling users what a good password policy is, ask them if they can explain the best practices for passwords and discuss what makes a good password. Another example is for trainees to discuss the types of malware they have encountered in the past, how they think it got on their computers, and what they think the attacker was after. This will help to illustrate to users that malware isn't just an inconvenience that slows down their computer, but is an attempt by online criminals to steal data off of their computers, to use their computer as part of a botnet, to use their computer to hide child porn and other contraband, or to use their computer to gain a beachhead to further their attack on the organization's network and steal more data. Both of these examples involve discussion but both could make a good writing and discussion exercise if you ask them to write down their answers and then discuss them. Another exercise would be to have the trainees to read one or more of the organization's security policies and then to reflect on why the policy is in place and to question why the organization needs such a policy.

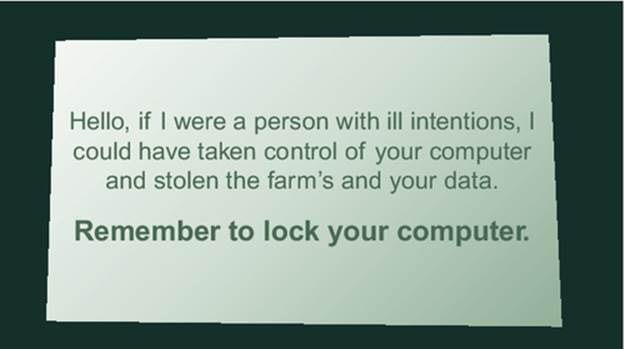

As you can see, this can be a process that takes more than a few minutes when an employee starts or an hour during the yearly security awareness day. Active learning exercises will require an organization to implement a continuous learning paradigm (Figure 6.1). One personal example of this is the reminder cards I left on people's desks when they did not lock their computer screens.

FIGURE 6.1 Screen locking reminder card.

While users found the reminder intrusive, over time, we had people become more compliant with the policy. Security awareness programs will become more effective if organizations place more time, money, and value in them. Once a year is not enough. A quick look at the news of continuing breaches because of social engineering attacks or a quick look at http://www.ponemon.org/ at the ongoing costs of data breaches should be enough to illustrate that while security awareness programs are getting better, we are not doing enough. Organizations spend millions of dollars a year on security products to protect their network edge. Organizations also need to start giving time and money to security awareness programs to protect themselves, their business partners, and their customers from social engineering attacks.

Building a security awareness program is a process. The most important thing one can do is to begin that process with the end in mind. No organization will be totally secure and no security awareness program will completely protect you from breaches. Breaches will still happen, but with the right amount of effort, you can make your organization more secure and hopefully less likely to suffer a breach from social engineering.

Notes

[1] Is the Lecture Dead? http://www.theatlantic.com/health/archive/2013/01/is-the-lecture-dead/272578/ [accessed on 24.10.2013].

[2] Twilight of the Lecture. http://harvardmagazine.com/2012/03/twilight-of-the-lecture [accessed on 24.10.2013].

[3] The Physics Suite: Peer Instruction Problems. http://www.physics.umd.edu/perg/role/PIProbs/ [accessed on 24.10.2013].

[4] How to Ignite Peer to Peer learning with Games http://www.quora.com/Michelle-Jaramilla/Posts/How-to-Ignite-Peer-to-Peer-Learning-with-GamesHow-to-Ignite-Peer-to-Peer-Learning-with-Games [accessed on 24.10.2013].

[5] On Security Awareness Training http://www.darkreading.com/hacked-off/on-security-awareness-training/240151108 [accessed on 29.11.2013].

[6] Does Security Awareness Training Actually Improve Enterprise Security http://www.safelightsecurity.com/does-security-awareness-training-actually-improve-enterprise-security/ [accessed on 29.11.2013].

[7] The Debate on Security Education and Awareness https://www.trustedsec.com/march-2013/the-debate-on-security-education-and-awareness/ [accessed on 29.11.2013].

[8] The Process of Security https://www.schneier.com/essay-062.html [accessed on 29.11.2013].

[9] Overview of Learning Styles http://www.learning-styles-online.com/overview/ [accessed on 24.05.2014].

[10] The use of learning style innovations to improve retention http://ieeexplore.ieee.org/xpl/login.jsp?tp=&arnumber=483166&url=http%3A%2F%2Fieeexplore.ieee.org%2Fxpls%2Fabs_all.jsp%3Farnumber%3D483166 [accessed on 24.05.2014].

[11] Do Hands-On, Technology-Based Activities Enhance Learning by Reinforcing Cognitive Knowledge and Retention? http://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ458788.pdf [accessed on 24.05.2014].

[12] University of Minnesota Center for Teaching and Learning http://www1.umn.edu/ohr/teachlearn/tutorials/active/ [accessed on 24.05.2014].