Information Security Management Handbook, Sixth Edition (2012)

DOMAIN 3: INFORMATION SECURITY AND RISK MANAGEMENT

Risk Management

Chapter 5. Continuous Monitoring: Extremely Valuable to Deploy within Reason

Foster J. Henderson and Mark A. Podracky

Introduction

Given the media coverage of the U.S. government’s information technology (IT) continuous monitoring requirements over the last 12 months, it is understandable how some individuals may have been led to believe that continuous monitoring is something new. The requirement to perform continuous monitoring has been around even before the Federal Information Security Management Act (FISMA) of 2002 was enacted. For example, the Department of Defense (DoD) Information Technology Security Certification and Accreditation Process (DITSCAP) Application Manual (2000, 113) stated, “effective management of the risk continuously evaluates the threats that the system is exposed to, evaluates the capabilities of the system and environment to minimize the risk, and balances the security measures against cost and system performance.” Furthermore, the document stated that the Designated Approving Authority, users, security practitioners, etc., continuously perform evaluations as a method to ensure secure system management (DoD, 2000). It is safe to say that the Office of Management and Budget’s (OMB) Circular A-130 Appendix III intended the requirement for continuous monitoring (NIST, 2010a, 2010b).

Continuous monitoring, implemented with sound rationale and procedures (i.e., an organization’s goals and level of risk acceptance taken into consideration against an organization’s functional business practices/mission objectives), is a powerful capability to assist IT security practitioners, authorizing officials (AOs), or designated accrediting authorities (DAAs) in their respective decision-making processes. That is in contrast to individuals who incorrectly contend that continuous monitoring will supplant the current certification and accreditation (C&A) process within the U.S. federal government, “… continuous monitoring can support ongoing authorization decisions. Continuous monitoring supports, but does not supplant, the need for system reauthorization” (NIST, 2010a, 2010b, p. 1). The intent of this chapter is to discuss the key components of continuous monitoring, provide recommendations to assist others with continuous monitoring planning, and provide rationale for why continuous monitoring will not supplant existing authorization (i.e., accreditation) procedures.

Background

In the past, the U.S. federal government has released several key IT regulatory provisions. The following is a list of key IT regulatory policies provided in chronological order:

1. Computer Security Act of 1987

2. Paper Reduction Act 1995

3. Clinger–Cohen Act of 1996

4. OMB Circular A 130 Appendix III, 1997 (NIST, 2010a, 2010b)

5. Government Information Security Reform Act (GISRA) enacted 2000

6. FISMA

GISRA’s requirements leveraged the key existing requirements from earlier regulatory governance predecessors (What is.com, 2008). The main difference with the early predecessors of GISRA is that the annual compliance reporting of federal departments and agencies was to be tied to their budgetary cycles. Specifically, noncompliance threatened organizations with having portions of their IT fiscal budgets removed. However, the problem with GISRA is that

![]() It lacked detailed guidance provided to federal agencies to meet its goals (i.e., lack of a uniform set of IT controls across the government) (What is.com, 2008).

It lacked detailed guidance provided to federal agencies to meet its goals (i.e., lack of a uniform set of IT controls across the government) (What is.com, 2008).

– “Specific standards for defined risk levels would not only have helped agencies ensure compliance, but provide a standard framework for assessment, ensure the adequate protection of shared data and reduce the effort—and resources—required to achieve GISRA compliance” (What is.com, 2008, para 4).

![]() It produced labor-intensive data calls (i.e., calling/e-mailing agency’s subordinate units in an attempt to populate the data fields of GISRA and stop work on other priority activities within the organization).

It produced labor-intensive data calls (i.e., calling/e-mailing agency’s subordinate units in an attempt to populate the data fields of GISRA and stop work on other priority activities within the organization).

– The absence of automated tools to assist in populating data fields was a consistently recognized problem.

![]() Organizations eventually discovered that being noncompliant would not result in the OMB or Congress withholding their IT budgets.

Organizations eventually discovered that being noncompliant would not result in the OMB or Congress withholding their IT budgets.

To say that 11 September 2001, changed many procedures within the federal government is a humble understatement. One of the by-products of 9/11 was the replacement of GISRA with FISMA in October 2002. My intent is not to discuss FISMA at the granular level, as there are several papers and articles addressing the topic. The nine key components of FISMA are as follows:

1. Risk assessment—categorize the IT and information according to the risk.

2. Inventory of IT systems

3. System security plans (SSPs)

4. Security awareness training

5. Security controls

6. C&A

7. Incident response/reporting security incidents

8. Continuity planning

9. Continuous monitoring (NIST, 2010a, 2010b)

Federal Desktop Core Configuration

The Federal Desktop Core Configuration (FDCC) is an OMB-mandated security configuration. The FDCC settings currently exist for Microsoft’s Windows XP service pack 3 and Vista operating system (OS) software. Although not addressed specifically as the FDCC, the requirement is within OMB memorandum M-07-11 (OMB, 2007). Memorandum M-07-11 was addressed to all federal agencies and department heads and a corresponding memorandum from OMB was addressed to all federal agencies and department chief information officers (CIOs).

How Was FDCC Created?

The National Security Agency’s (NSA’s) Red Team visited the Armed Forces during one of their periodic network exercises. Subsequently, in the early 2000s, the Air Force CIO requested assistance to develop standard desktop configurations and hardening guidance with assistance from NSA and the Defense Information Security Agency (DISA) as remediation based upon the action items from the recent NSA Red Team exercise. It was later realized that a very large percentage of network incidents could have been avoided if the available patches had been applied or the available hardening guidance had been used. From tracking information assurance vulnerability alert (IAVA) (i.e., U.S. Strategic Command’s Joint Task Force—Computer Network Operations vulnerability messages based upon the Common Vulnerabilities Exposures [CVEs]) compliances, the Air Force leadership realized that the time to apply a software patch took well over 100 days in some instances. An internal lean engineer process meeting was held; recommendations and a list of action items were tracked and that number shrank to 57 days. Later, through an enterprisewide standard desktop configuration deployment, that time was reduced from 57 days to less than 72 hours. In 2007, a group of cyber security experts stated that this U.S. Air Force proof of concept was one of the most significant successes in cyber security (Mosquera, 2007).

U.S. Government Configuration Baseline

The FDCC mandate later evolved into the U.S. Government Configuration Baseline (USGCB). USGCB is a federal governmentwide initiative that provides guidance on what can be done to improve and maintain effective configuration settings, focusing primarily on security. Specifically, its charge is to create security configuration baselines for IT products deployed across federal agencies. USGCB is now a required task under the latest FISMA guidance from OMB.

The Requirement (Continuous Monitoring)

IT Security in the federal government has undergone a paradigm shift to continuous monitoring, as indicated by the slew of recent National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) and OMB communications. For example, the OMB’s memorandum M-10-15, titled FY 2010 Reporting Instructions for the FISMA and Agency Privacy Management, mandated continuous monitoring. This document placed the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) in charge of continuous monitoring (i.e., the monitoring and reporting of federal agencies’ compliance) (OMB, 2010). NIST recently defined continuous monitoring as

…maintaining ongoing awareness of information security, vulnerabilities, and threats to support organization risk management decisions. The objective is to conduct ongoing monitoring of the security of an organization’s network, information and systems, and respond by accepting, avoiding/rejecting, transferring/sharing, or mitigating risk as situations arise (NIST, 2010a, 2010b, p. 1).

NIST provides excellent guidance on continuous monitoring within Special Publications (SP) (draft) 800-137, Information Security Continuous Monitoring for Federal Information Systems. Rather than recite and repackage the draft SP contents for the reader, this chapter restates the high-level aspects and provides specific examples to better assist individuals in their specific continuous monitoring implementations. For additional details, it is recommended to reference draft SP 800-137.

Reviewing NIST’s executive summary (i.e., SP 800-137), continuous monitoring can be explicated using the following list.

1. Define the strategy.

2. Establish measures and metrics.

3. Establish monitoring and assessment frequencies.

4. Implement a continuous monitoring program.

5. Analyze the data and report the findings.

6. Respond with mitigating strategies.

7. Review and improve the program (NIST, 2010a, 2010b).

Admittedly, this may be overly simplistic, as there are many underlying disciplines to support the above categories—the majority of those disciplines are addressed in the next section.

Define the Strategy

Plan the work and do the work according to the plan—this is a basic project management statement. An individual has to understand that continuous monitoring is more of a system engineering/project management effort that is processing IT security data than being a purely information security effort. For example, what are the needs and requirements of the stakeholders? What is the overall purpose or objective of the task? The answers are fundamental project management principles. SP 800-137 discusses a three-tiered approach for applying continuous monitoring throughout an organization.

1. Tier 1 is described as those tasks that provide governance/risk management for an organization; e.g., policies, strategic planning, vision, and overall risk management governing the entire organization.

2. Tier 2 is the core business functional requirements or mission objectives/goals for an organization.

3. Tier 3 is the information system and the user requirements that the IT system is fulfilling. Specifically, the technical, administrative (i.e., training), and physical controls required for protecting IT systems and enabling the users (NIST, 2010a, 2010b).

This may sound complicated, but it is actually simple, considering that this approach is further broken down into work breakdown structures (WBS) and the realization that a large portion of the WBS should have been accomplished by the organization’s CIO (federal side). For example, NIST separates the continuous monitoring process into nine steps, as documented by the Risk Management Framework (RMF) from SP 800-37 Revision 1: Applying the RMF to federal information systems. Step 1 of the RMF states to categorize the information system.

Any security practitioner with at least 3–4 years of experience securing federal IT systems should know to review the Federal Information Processing Standards (FIPS) 199, Security Categorization of Federal Information and Information Systems, codes within their organization’s respective portfolio management directory, database, or their cloud. For clarification, simply reviewing an organization’s FIPS 199 categorization codes for those individual IT systems used to fulfill its mission or goal would meet that requirement. The DoD terms it Mission Assurance Category (MAC) codes in accordance with DoD Instruction 8510.01, DoD Information Assurance Certification and Accreditation Process for top secret and below classified rated systems.

Steps 2–4 of NIST’s RMF process include selecting, implementing, and assessing the security controls, respectively. As previously mentioned in the section: U.S. Government Configuration Baseline, the OMB has mandated NIST’s USGCB (i.e., addresses the desktop controls suggested within NIST’s RMF Steps 2 and 3). To further streamline and define the strategy, a continuous monitoring strategy recommendations are listed. However, the recommendations must be based upon the organization’s “as is” architecture model or must support the “to be” architecture model (i.e., depending on the current status of the architecture model if it is going through a transition process).

1. Identify the best tool or available tools for the job (understand the continuous monitoring capability from each vendor and their tools. Security Content Automation Protocol Validated Products use is critical to not making one’s life difficult). (Reference NIST’s http://nvd.nist.gov/scapproducts.cfm URL for additional details.) In addition, the SPAWAR tool is a government off-the-shelf tools (GOTS) product and it is free to federal government entities.

2. Install/deploy network-monitoring tools currently not available.

3. Connect those tools’ output to a central repository.

4. Determine which process to conduct (manual or automated collection).

5. It is recommended to initially conduct continuous monitoring on a monthly basis until the system administrators, the leadership’s expectation, and the reporting process become fairly routine. This assumes that the reporting process (i.e., the data output) adjustments were made. For example, the data were reviewed (no issues) and the processes were streamlined internally.

For further clarification, the Common Platform Enumeration (CPE) (i.e., the list of OS by version), the CVE (i.e., the false-positives from the scanning tool are validated), and the Common Configuration Enumeration (CCE) values are properly reconciled. That is, they are compliant with NIST’s USGCB and the respective OS hardening guidance from NSA or DISA’s Security Technical Implementation Guides (STIGs). Was the scanning tool’s latest signature pulled down from the vendor? What is the frequency of those updates? These are the types of issues that have to be considered within the continuous monitoring strategy.

Based upon experience, these items are communicated within the existing C&A plan, the SSP, and the organization’s standard operating procedures. By now, it should be apparently clear why continuous monitoring supports, but will not supplant, the C&A process.

Based upon the current commercial monitoring technologies used within the federal government (i.e., admittedly excluding Einstein, NSA, or other GOTS tools), the following are the recommended continuous monitoring automated process areas to adapt.

1. Asset management

2. Vulnerability management

3. Configuration management

a. It is critical that an organization has an internal mature configuration control process. For example, a current client has an exorbitant number of printers that need to be phased out and reduced. The USGCB Windows 7 setting breaks a large portion of those printers. To make matters worse, the vendor’s universal printer drive does not work, but it is stated as USGCB compliant. The only solution is to use Windows update to get the driver directly from Microsoft. Therefore, one is faced with either not supporting those printers (i.e., legacy) or providing a list of approved printers to users during a continuing resolution (as of writing this chapter) when we cannot purchase Jack Schmidt! The problem in this example is that the configuration management process was not being followed nor was there any guidance provided.

b. It is literally akin to the Wild Wild West with purchases being made in FY 10 not supporting the Windows 7 USGCB images. The second issue includes JAVA runtime updates that are frequently pushed. It has been our experience that this breaks several USGCB settings and increases trouble tickets within the organization. It is thus recommended to place these updates in a control approval process as well.

4. Malware detection

5. Patch management

6. Log integration

7. Security information and event management (SIEM)

As previously mentioned in this section, it is recommended that a manual process from the various tools collected data be used first, before fully automating the continuous monitoring reporting. This way it is easier to make comparisons between the automated process’ output and the earlier collected manual feeds (i.e., placed in an Excel spreadsheet and then pushed via an XML format) and make the necessary adjustments, because there is a working experience and baseline in which to perform an initial comparison (i.e., after the initial investigations/verification have been performed to validate the information).

Establish Measures and Metrics

Guidance on the specific metrics within the federal government related to FISMA compliance comes from OMB. The issue is that OMB yearly FISMA guidance is usually released 5–6 months into the fiscal year’s reporting cycle. It is recommended to have a list of metrics for internal stakeholders and external stakeholders. The external stakeholders would be OMB, the U.S. Computer Emergency Response Team, DHS, etc. The internal stakeholders are the organization’s internal leadership and the IT security practitioners (CIO, chief information security officer, information system security manager, etc.). The following are possible metrics based upon the seven earlier recommended continuous monitoring automated processes.

Asset Management

![]() Blocking of unauthorized network connections.

Blocking of unauthorized network connections.

![]() Blocking of unauthorized devices (mobile phones [excludes BlackBerry given its prevalent use within the federal government], unapproved unencrypted USB flash drives, cameras, etc.). Don’t you love your users’ colleagues?

Blocking of unauthorized devices (mobile phones [excludes BlackBerry given its prevalent use within the federal government], unapproved unencrypted USB flash drives, cameras, etc.). Don’t you love your users’ colleagues?

Vulnerability Management

![]() Know the list of vulnerabilities marked by criticality codes.

Know the list of vulnerabilities marked by criticality codes.

Configuration Management

![]() FDCC/USGCB compliance (scan for compliance with NIST’s latest guidance)

FDCC/USGCB compliance (scan for compliance with NIST’s latest guidance)

![]() DISA STIG, SANS, or NSA hardening guidance compliance

DISA STIG, SANS, or NSA hardening guidance compliance

![]() Port and Protocol compliance (based upon deny all, allow by exception)

Port and Protocol compliance (based upon deny all, allow by exception)

![]() Prohibit authorized remote connections not meeting the configuration guidance (i.e., place in demilitraized zone (DMZ) or some similar quarantined area until all patches are applied)

Prohibit authorized remote connections not meeting the configuration guidance (i.e., place in demilitraized zone (DMZ) or some similar quarantined area until all patches are applied)

![]() Data feed of connected network devices (includes wireless devices)

Data feed of connected network devices (includes wireless devices)

Malware Detection

![]() Age of virus signatures against current baseline

Age of virus signatures against current baseline

Patch Management

![]() Compliance with NIST’s national CVE database or U.S. Cyber Command IAVAs (percentage-based)

Compliance with NIST’s national CVE database or U.S. Cyber Command IAVAs (percentage-based)

Log Integration/SIEM

![]() Viruses not deleted (my client has over 1 million events per day so my colleagues’ pain is clearly understood)

Viruses not deleted (my client has over 1 million events per day so my colleagues’ pain is clearly understood)

![]() Enabling or disabling of accounts (user and admin)

Enabling or disabling of accounts (user and admin)

Establish Monitoring and Assessment Frequencies

This was sufficiently covered earlier as an individual can see that there were some overlaps mentioned from the previous section and within the section: Define the Strategy. One lesson learned is to use a test Active Directory organization unit (OU) to monitor how a patch or other software will impact the USCGB settings. Specifically, it is recommended to create a baseline before installation, during the installation, and on removal of the software to see how the USGCB settings are changed. This needs to be monitored, otherwise an individual will increase the help desk calls when an unexpected value changes the USGCB settings. It should be noted that a large portion of applications (i.e., commercial) are okay, but it was the custom applications that generally wreaked havoc upon our organization.

Implement Continuous Monitoring Program

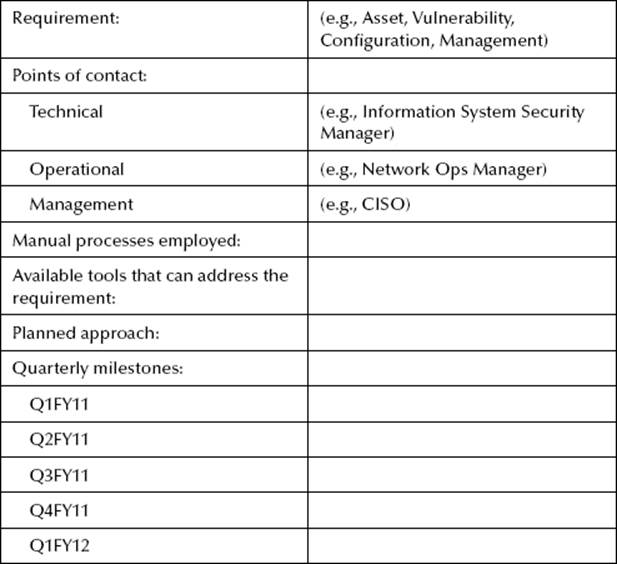

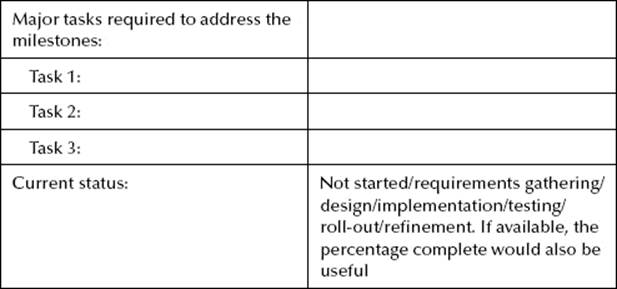

After the organizational continuous monitoring strategy has been completed (internally) or provided from a higher level (i.e., headquarters or the parent organization level), it is suggested that a continuous monitoring implementation plan be drafted to communicate to internal stakeholders the “who, what, when, where, and with what” tools that are going to be used. This document needs to be agreed upon and approved internally. The following chart was provided by a colleague to communicate the high-level functions, milestone dates, and other pertinent information. For clarification, each area—i.e., of the seven earlier recommended continuous monitoring automated processes—data fields need to be completed. This assumes that the deficiencies are being tracked and mitigated, although this is not communicated within the chart (by the respective owners). For example, the plans of action of milestones (i.e., the get-well plan to eliminate the issues or trends from the scans impacting the organization) are being tracked until resolved.

Limitation of Continuous Monitoring

At the beginning of the chapter, I noted that continuous monitoring cannot supplant existing authorization procedures. Instead, it supports the process. By now, it is apparent that continuous monitoring cannot present an overall comprehensive risk management plan for an entire organization. Specifically, not all of NIST’s SP 800-53 Revision 3: Recommended security controls for federal information systems and organizations can be fully automated. As examples, contingency planning, other similar administrative controls, and some physical controls cannot be automated when performing a C&A. Yes, although the expiration dates can be tracked in C&A tools, such as Trusted Agent FISMA, Xacta’s IA Manager, Enterprise Mission Assurance Support Service (eMASS), etc., those respective disciplines and procedures involve people and processes and will remain a manual process.

It is not my intent to embarrass an organization or fellow colleague. Rather, the following example is used to illustrate a point. I recall reading Federal Computer Weekly and a similar article, which stated how the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) had saved money by doing away with the old C&A process and adopting a continuous monitoring procedure. They testified about their “success” before the Congress (FCW, 2010). Several months passed and I happened to notice a rather interesting article, which described how NASA failed to remove or sanitize sensitive data when it released 14 previously used computers to the public (Gooding, 2010). Furthermore, at a disposal facility, auditors discovered computers containing NASA’s Internet Protocol addresses as well as the fact that NASA had authorized the release of other computers that were subject to export controls (Gooding, 2010).

Recently, an article by Jackson (2010) detailed a State Department report that its “… high-risk security vulnerabilities were reduced by 90 percent from July 2008 to July 2009 and the cost of certifying and accrediting IT systems required under FISMA was cut by 62 percent by continuously updating security data” (para 8). That is an excellent accomplishment and an excellent success story. The point is that metric is addressing technical controls. It is not the total picture. And to take this a step further, one need to look no further than the State Department’s recent issue with Wikileaks. Yes, an Army private first class was responsible for the damage, but a substantial portion of the files that he retrieved were from the State Department. IT experts have indicated that this would not have happened had we (as a community) done “X, Y, and Z.” This should have been in place, etc. “You hypocrite, first cast out the beam out of your own eye; and then shall you see clearly to cast out the mote out of your brother’s eye” (Matt. 7:5 King James Version). Most of the commercial sector does not even perform background investigations (it costs money) on employees unless their work requires a U.S. government clearance. Almost every other month there seems to be some “Insider” article about someone who has burned a commercial organization. The Computer Security Institute’s annual Computer Crime and Security Surveys and Verizon’s 2008–2010 data breach reports should validate my claim (i.e., growing insider threat) (Verizon, 2009).

Conclusion

Continuous monitoring is a very important key to successfully strengthen and validate the FISMA reporting, and this is an improvement over what has occurred in the past. However, its mandated use should be expedited throughout the federal government as OMB intends. As communicated several times throughout this chapter, continuous monitoring is a key component to leverage the accreditation process.

References

DoD. Department of Defense Manual 8510.1-M, Department of Defense Information Technology Security Certification and Accreditation Process (DITSCAP). Assistant Secretary of Defense Command, Control, Communications, and Intelligence, 2000.

DoD. Department of Defense Instruction 8510.01, DoD Information Assurance Certification and Accreditation Process (DIACAP). Assistant Secretary of Defense Networks and Information Integration (ASD NII), 2007.

Federal Computer Weekly News. NASA FISMA stance stirs up a debate: Readers still see value in certification and accreditation, 2010. http://fcw.com/articles/2010/06/14/fcw-challenge-fisma-nasa.aspx (accessed February 27, 2010).

Gooding, D. NASA sells PC with restricted space shuttle data: Disk wiping? We’ve heard about it. The Register, 2010. http://www.theregister.co.uk/2010/12/08/nasa_disk_wiping_failure/ (accessed February 26, 2010).

Jackson, W. FISMA’s future may lie in state department security model: FISMA re-working is increasingly likely. Government Computer News, 2010. http://gcn.com/articles/2010/03/03/rsa-futue-of-fisma.aspx (accessed January 23, 2011).

Mosquera, M. Air force desktop initiative named top cybersuccess story. Federal Computer Weekly, 2007. http://fcw.com/articles/2007/12/13/air-force-desktop-initiative-named-top-cybersecurity-success-story.aspx (accessed January 23, 2011).

National Institute of Standards and Technology. Special Publications 800-137 DRAFT Information Security Continuous Monitoring for Federal Information Systems and Organizations, 2010a. http://csrc.nist.gov/publications/drafts/800-137/draft-SP-800-137-IPD.pdf (accessed February 6, 2011).

National Institute of Standards and Technology. FISMA detailed overview, 2010b. http://csrc.nist.gov/groups/SMA/fisma/overview.html (accessed February 20, 2011).

Office of Management and Budget. OMB Memo 07-11, Implementation of Commonly Accepted Security Configurations for Windows Operating Systems, 2007. http://www.whitehouse.gov/sites/default/files/omb/assets/omb/memoranda/fy2007/m07-11.pdf (accessed February 12, 2011).

Office of Management and Budget. OMB Memo 10-15, FY 2010 Reporting Instructions for the Federal Information Security Management Act and Agency Privacy Management, 2010. http://www.whitehouse.gov/sites/default/files/omb/assets/memoranda_2010/m10-15.pdf (accessed February 20, 2011).

Verizon. Data breach investigation report, 2009. http://www.verizonbusiness.com/resources/reports/rp_2010-data-breach-report_en_xg.pdf (accessed March 1, 2011).

Whatis.com. Government Information Security Reform Act, 2008. http://whatis.techtarget.com/definition/government-information-security-reform-act.html (accessed February 20, 2011).