Information Security Management Handbook, Sixth Edition (2012)

DOMAIN 3: INFORMATION SECURITY AND RISK MANAGEMENT

Risk Management

Chapter 4. The Information Security Auditors Have Arrived, Now What?

Todd Fitzgerald

Introduction

Auditors perform an essential role in protecting the information assets of an organization, which should be embraced rather than feared. Many times, when an audit is scheduled, whether internally or externally initiated, the response is one of fear of what the auditors will find as gaps in the information security program. Analogous to how many people feel when they are scheduled for their annual performance review, anxiety is almost certain to be a normal response. Why is it that way? The answer is simple—no one likes to be criticized for what they have put their best efforts into, and just like the potentially stressful performance reviews, audits have the potential to be taken very personally and viewed as a negative experience.

The truth is that audits typically do cause anxiety and cause people’s stress levels and outward emotions to reflect the pressure of being “judged.” The truth is also that audits can be extremely valuable learning experiences by which those leading the information security programs can learn greatly from the auditors. Auditors are typically very detail oriented and as a result may see items that may be overlooked by the big-picture people. Auditors also typically follow a methodical, systematic approach to analyzing what the organization asserts are the controls that are in place. This systematic approach allows the auditors to uncover what may be assumed is actually occurring by the company. For example, a manager may assume that a policy in place requiring all access be terminated for an exiting employee within 72 hours is being followed. When the auditor reviews the policy, he may find that there was no documented standard operating procedure, thus raising doubts that a consistent procedure was actually being followed. The auditor may also find that while logical access was promptly removed, there was no equivalent procedure within physical security, thus creating a gap. Many times, the auditor will request a full population of employees and subsequently request a random sample, say 25, and test to determine if the requirement was consistently met.

How often do the operational departments within an organization perform an independent test of the product or service they are creating? Companies are doing their utmost best to just get the product or service out the door. This creates a situation where compliance with the company’s policies, procedures, standards, and guidelines is assumed, but is not regularly tested. In this respect, we should be welcoming the auditors with open arms!

A by-product of performing audits on a regular basis is that managers are more apt to pay attention to ensure that the standard operating procedures are actually accurate and reviewed on a periodic basis (minimally on an annual basis). Knowing that they will be judged on the basis of what process is written versus the current process, if different, even if the current process is better, will encourage managers to take the documentation more seriously. Documentation should be regarded as management directives to ensure that the appropriate activities are being performed at the right time.

From experience gained through dozens of audits involving the Big Four accounting firms, audit firms occupying the middle-market tier, and boutique technical auditing firms, it is safe to say that no two audits are conducted the same way or necessarily have the same goals in mind. However, there are some basic commonalities to the flow of an audit and how the information security department should interact with the auditors. The following sections discuss the anatomy of an IT audit and how the security professional should best prepare for the audit.

Anatomy of an Audit

From a security officer’s point of view, the audit can be separated into five phases: (1) Planning, (2) On-site arrival, (3) Audit execution, (4) Entrance/status/exit conferences, and (5) Report issuance and remediation. It is useful to look at the audit as a project, with a discrete set of steps, a beginning, and an end. Viewing the audit as an activity in this manner permits the prioritizing, scheduling, and resourcing of the audit similar to other projects within the company. The success of an audit depends upon having knowledgeable individuals available to answer the questions for which they are most qualified at the appropriate time.

External audits involve an upfront period of negotiation for the scope and pricing of the audit. This process is normally administered through the company’s internal audit department in response to a contractual requirement for a piece of awarded business (i.e., government contract with FISMA provisions or HIPAA compliance requirements). Because internal audit may have many internal/external audits scheduled during a given year, the audit may not occur at the best time for the IT department to have the resources available. Partnership with internal audit, information security, information technology, and compliance areas can help mitigate the scheduling disruptions that can occur. Once the external audit dates are set, there is typically limited flexibility to move the schedule, as the external audit firms must also balance their resources with the needs of other clients. Typically, teams are only put together a few weeks at the most for the audit firm, but once they are, they tend to be “locked in.”

The following phases assume that the contract and the schedule are now in place and Information security and the other departments need to prepare for the audit.

Planning Phase

Preparation of Document Request List

The first step is to establish an audit coordinator for the information security/IT portion of the audit. This individual is usually someone within the IT organization who understands the interoperability of the technical infrastructure, operations, and management of IT. Internal audit departments traditionally focus on the Financial and Operational audit areas and may or may not have the IT auditing skills. Even if they do have individuals with these skills, their role is to audit the organization. The role of the audit coordinator is to respond to the requests of the auditors, which may be internal or external. To mitigate any conflict of interest questions (auditors preparing responses to their own managed audits), an audit coordinator position is established. The function of this individual is to coordinate all audit requests, ensure timely receipt and delivery of the artifacts, schedule meetings, communicate issues, and generally ensure that a smooth process is followed.

Anywhere from 3 to 5 weeks ahead of the audit, the auditors will prepare and deliver a request for documentation. The request goes by such names as Prepared By Client (PBC) listing, Client Assistance List (CAL), Agreed-Upon Procedures (AUPs), etc. Regardless of the name, the intent of the request is the same—a document typically in the form of a Word document or a spreadsheet that contains the auditor’s request for documentation that they would like to have available when they start the audit. It is in everyone’s best interest to comply with the request and have 100 percent of the requested items available when the auditors start the audit. This permits the auditors to immediately start reviewing and understanding the materials provided. By supplying all of the information at the beginning, it can also reduce the stress level by avoiding hurry-up requests that must be immediately supplied to the auditors. There will also be additional requests by the auditors that will consume valuable time during the audit, so it makes sense to solicit the materials in advance and give the departments as much of the 3–5 weeks’ time as necessary to collect the artifacts. The failure to adequately allow ample preparation time causes the organization to respond “on the fly” and not necessarily provide the best responses due to the short time frame allowed during the audit to provide the responses.

If any of the audit requests are not clear, the audit coordinator may need to schedule a meeting to discuss the deliverables requested. The scope may not be clearly understood by the auditors or the client. As new auditors are brought into an engagement, they must quickly come up to speed with the organization, processes, and the business operations. Because the request list is typically based upon a generic template, assumptions may be made about the processing that is performed by the company being audited. For example, it may be assumed that the company is following a system development life cycle (SDLC) process to develop software, when in fact the organization may have outsourced the development and maintenance activities to a system integrator and is running these processes from a data center. If the audit of the data center is also in scope, the SDLC processes can be obtained through a separate audit of the data center.

The requests are usually organized into sections deemed important by the auditor and may or may not be numbered. The number of items requested varies, but typically 50–200 requests for different security elements are normal. There is little consistency between audit firms as to what is requested, as each audit firm has constructed their audit program based upon what they consider to be important, modified by the focus desired by the organization or the branch of government requesting the audit. The number of auditors and scope may dictate how much testing is performed within the audit. An audit that has 2–3 auditors on site for 1–3 weeks will involve substantially less testing than a 4-week audit with 10 auditors on site.

A description of the contents of the request, an associated control ID, dates requested and dates received, and a field for comments are typical components of a document request list. One item that is not stated is how this document will be used within the audit! The auditors do not necessarily tie the request to the control item being tested, nor do they necessarily want to make this clear. After all, this is an audit to test the operations, and if they are testing to determine if the controls are adequate to protect the information assets, then it should be irrelevant if the company knows what control is being tested when the documentation request is made—the organization should have the document in question. On the other hand, it helps to know the context of the request, to supply the correct documentation.

Once the request list is received, the items should be assigned an internal control number for tracking. This helps tremendously during the audit, to track and determine what has and what has not been provided. The next step is to determine which (1) Director, (2) Manager, and (3) Subject matter expert, or primary point of contact, is in the best position, in terms of knowledge, to respond to the request. The documentation request list can be modified to place these accountable and responsible positions in columns for each request so that it is clear who will own this deliverable. Although it may seem obvious, it is vitally important to establish who the correct owners are up front, or time ends up being wasted when a manager indicates the day before the deliverable is due that they are not the correct owner. This action is unfair to the manager who now needs to scramble to complete the request and does not promote the generation of a quality product.

The updated spreadsheet with the internal tracking numbers, accountable management, and subject matter experts is then distributed to the organization by the audit coordinator, typically within 1 week after receiving the initial request list. The managers should be given a couple of days to receive the listing and confirm that the items are theirs, and if not, recommend who should own the requested item. At this point, they are not fulfilling the request, but merely indicating whether or not it is theirs to supply. It is best to place the responsibility with the assigned manager to reach an agreement with the department manager on who should own the request and inform the audit coordinator. This avoids multiple conversations between the audit coordinator and each party, which can potentially increase the time to gain agreement due to the unavailability of all parties to the conversation.

Now that the documentation requests each have an owner associated with them, each owner can now begin the process of collecting the artifacts for submission. The audit coordinator should create an audit artifact repository of some sort to capture and organize the artifacts. This may be a simple directory structure, containing one folder for each item on the request list (the folder will most likely contain multiple documents to satisfy the request), or it may be a more elaborate homegrown database or vendor-created database. Either of these methods is preferred to subject matter experts sending the requests via e-mail, as the file sizes can typically exceed the internal 5/10MB limitations of the e-mail service or the storage of the audit participants. Additionally, when others need to look up the audit artifacts that have been supplied, without a central network storage area, they may or may not have been the recipient of the initial e-mail and will have to request that the information be forwarded again. This, in turn, increases the company’s storage requirements and is very inefficient.

Gather Audit Artifacts

Once each manager has accumulated all of the artifacts assigned to him for the audit, the manager needs to confirm with the audit coordinator that the collection is complete. At this point, the audit coordinator can review the contents and determine whether or not all of the information has been provided. This quality assurance process increases the likelihood that the information will not have to be re-requested. The auditor coordinator looks for such discrepancies as:

![]() Accuracy spot-check: Check to determine if the information supplied matches the information requested.

Accuracy spot-check: Check to determine if the information supplied matches the information requested.

![]() Empty folders: Contents may have been placed in a different audit directory, accidently deleted, moved to another folder, or misplaced. It all happens.

Empty folders: Contents may have been placed in a different audit directory, accidently deleted, moved to another folder, or misplaced. It all happens.

![]() An insufficient artifact: The audit coordinator has typically seen a similar request across audits over time and is usually in the best position to determine whether or not this artifact is complete.

An insufficient artifact: The audit coordinator has typically seen a similar request across audits over time and is usually in the best position to determine whether or not this artifact is complete.

![]() Time period not valid: If the audit is from 1 October 2012 to 31 March 2013 and a standard operating procedure updated on 4 August 2013 is supplied, the new procedure would not have been effective during the audit period.

Time period not valid: If the audit is from 1 October 2012 to 31 March 2013 and a standard operating procedure updated on 4 August 2013 is supplied, the new procedure would not have been effective during the audit period.

![]() Sizes too large: If the file sizes are too large, say >10MB, then it may be difficult if the files need to be subsequently e-mailed to the auditor. It is best to break these directories into subdirectories prior to the audit.

Sizes too large: If the file sizes are too large, say >10MB, then it may be difficult if the files need to be subsequently e-mailed to the auditor. It is best to break these directories into subdirectories prior to the audit.

![]() Outdated policies/procedures: A quick review of the last update date would indicate whether or not this might be an old artifact.

Outdated policies/procedures: A quick review of the last update date would indicate whether or not this might be an old artifact.

While the management and subject matter experts are responsible for ensuring that the audit artifacts are accurate and comply with the information request, the spot-checking by the audit coordinator is a value-added step that can find problems with the information prior to its presentation to the auditors.

Provide Information to Auditors

Once the audit coordinator has collected all the information for the items requested on the document request list, the audit coordinator can burn an initial CD/DVD containing all of the information. Because much of the information will be highly confidential (network diagrams, access control lists, employee listings, background checks, logs, etc.), the information must be encrypted. Encryption programs have fallen in price substantially in the past few years, so there is little justifiable reason not to protect this information. Programs such as WinZip, SecureZip, PKZip, or programs based upon the zip format are used by most audit firms and can be opened by their auditors. This should be verified with the auditors prior to starting the engagement, as not all encryption programs are compatible. For example, a file encrypted using Pointsec software cannot be opened by Winzip or SecureZip because it uses a proprietary nonzip internal format. A self-extracting file may need to be created if using this type of software. However, a file encrypted by Winzip (version 9.0 or greater) or SecureZip can be opened by either program, because the internal format used in both products is based on the zip format. Providing multiple copies for the auditors is typically appreciated to enable them to ramp up quickly while on site without having to spend time copying sizable files across a network or waiting for others to complete copying the files to their disks. While most auditors utilize encrypted hard disks on their PCs to store the client files, it is advisable to confirm this with the auditors before providing them with the information.

Preparation for On-Site Audit

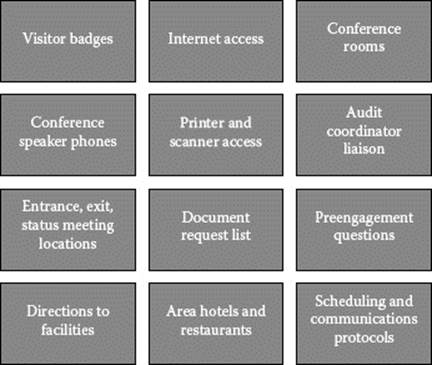

To ensure that the appropriate logistics have been taken care of, the auditors may schedule a pre–on-site meeting ahead of the audit. Figure 4.1 provides a complete listing of the items typically requested by the auditors in advance. The following sections discuss considerations for some of the key items requested by the auditors.

Figure 4.1 Listing of items typically requested in advance by auditors.

Internet Access

Even though the auditors are engaged at the client site, they still have responsibilities to their home office and need to communicate with other senior-level auditors and partners. They may need to share files, access e-mail, conduct conference calls, access home-office software, and so forth. One method of providing this access is to provide internal network access and subsequent access to the Internet. This involves setting up the auditors similar to how contractors may be connected to the system—with a user account on the network and access to the Internet. The problem with this configuration is that the auditors are now resident on the network and may have access to more network files than desired. Auditors should be treated with the same security “need-to-know” and “least-privilege” principles that are applied to other users of the organization’s information assets.

An alternative solution that serves to provide the access that the auditors need while simultaneously limiting the exposure of internal information outside the scope of the audit is to provide network access via a wireless broadband router. This relatively inexpensive solution provides the auditor with the access required and keeps the auditor from having to be set up on the organization’s computer network. Not only does this save time in setup, but it also provides a fast solution to deploy to the auditors. In other words, the day that the auditors arrive on site, the wireless broadband router can be plugged in and they are ready to begin work. The router also permits sharing of the broadband connection between the auditors. It is advisable to have one broadband router for every four auditors to ensure an adequate bandwidth when downloading/uploading large files.

Once the availability of this device is known within the company, it is not unusual for the IT department to have more requests than there are routers. Given the inexpensive nature of this piece of hardware (under $200 as of this writing) and the aircard monthly fees (generally $60/month or less depending upon pricing discounts and usage), it makes sense to ensure that there are extra routers that can be shipped to alternate audit locations to support the audit. The hidden costs of requesting accounts, setting up audit access, terminating accounts, requesting auditor names, etc., are greater than the one-time cost of the routers and monthly charges.

Reserve Conference Rooms

Depending upon the size and duration of the audit, a small or large conference room may be needed. The failure to provide a room with enough space for both the auditors and the auditees can create an environment that increases the stress levels of both parties. The proper size conference room for the interviews may not be known until the interview schedule has been created. Most organizations do not have extra conference rooms available, so these should be scheduled at the start of the audit.

The auditors may also request that a room be reserved for their private conversations, separate from the room reserved for the interviews and the other auditors. This permits sidebar discussions without disturbing the rest of the team. However, it is not unusual to see auditors with headphones on in large conference rooms to block out the distractions of the other auditors.

If possible, locate a conference room that is away from the individuals performing a bulk of the work that is being audited. This avoids embarrassing situations where someone may make a comment related to an aspect that is currently under audit and being overheard by the auditor. Although the comment may be accurate, it may be taken out of context by the auditor or substantiate an issue that the auditor was investigating. Staff should also be courteous to the auditors and respect the noise levels and conversations outside the conference room.

Temperature control is always a consideration. Although it may be tempting to smoke out or freeze the auditors, this strategy is ill-advised! While this may be obvious, keep in mind that there will be more individuals in the room at any onetime with the auditors and auditees and body heat will tend to raise the temperature.

Physical Access

The degree of physical access needs to be defined in advance: What building? What times? Must the auditors be escorted? How long can they keep their badges? Some auditors will be using their own experiences with the badging process to evaluate the physical visitor/consultant/employee/contractor security controls. If the visitor log policy indicates that an individual is supposed to obtain a badge and sign out at the end of each day and this function is not required of the auditors, then this may result in an audit finding based upon the lack of control enforcement. Or, if the policy is that the auditor must be escorted and the auditor finds that during the course of the audit, they were free to roam the building, this could also result in a finding.

Special auditor badges with predefined access and the requirement to conform to a separate auditor visitor policy are recommended. Auditors generally work until the early evening hours or start early, so a 7:00 a.m. to 7:00 p.m. access policy would satisfy most auditor needs. As far as escorting, auditors are being entrusted with vast amounts of confidential information to perform an audit, so the risk of damage by allowing the auditors into the building without an escort is low. Auditors could be granted access badges that permit entry during the week of their audit and be required to return the badges at the end of the fieldwork. Agreements with the auditors should be made that they will confine their activities to the conference rooms, restrooms, and break rooms without needing an escort, but if they need to visit other operational areas, then they must have an escort. The escort would preferably be the audit coordinator or his designate.

Conference Phones

Have you ever been on a phone conference call, seen someone shuffling papers, having a conversation on their cell phone, or heard dogs barking in the background? We all have, and it does not help the subject matter being discussed. A good quality conference phone, such as a Polycom, should be placed in each conference room where interviews will be held. Because interviews generally involve geographically dispersed individuals or will involve someone calling in while traveling, a phone will be required for the conference. The speakerphones on office phones are not designed to handle a room of people 4–8 ft. away from the phone. A better setup is to have a conference phone with two microphones attached by 3–4 ft. cords. The acoustics of the room should also be tested to ensure that outside, heating/air conditioning, or fan noise does not interfere with the sound quality level.

Schedule Entrance, Exit, Status Meetings

Each of these meetings should be scheduled at least 1 week in advance of the start of the audit, preferably 2 weeks or more, so that the appropriate management and technical staff can make themselves available to attend. Consideration should be given to those individuals who reside in different time zones, with the avoidance of a pre-8:00 a.m. meeting in any time zone if possible. Individuals should be at their best for the audit calls and for most staff, this would be during their normal workday hours.

Entrance Meeting

The audit entrance meeting provides the opportunity to ensure that the organization knows the scope of the audit, the expectations, and the key dates. The entrance meeting is often scheduled late Monday morning to early afternoon to allow for traveling. The auditors generally travel on Sunday night through Thursday evening or Monday morning through Friday evening to provide for some balance, because on-site auditors for the Big Four accounting firms are traveling 80–100 percent of the time, depending upon the contracts. Hopefully, the audit coordinator has communicated as much as possible to the organization prior to the arrival of the entrance meeting, as the preparation activities previously mentioned are needed to ensure that the documentation would be available for the entrance meeting. Some auditors will request that the documentation request list be provided as soon as possible, sometimes ahead of the entrance meeting, however, as is more often the case, the auditors tend to start looking at the materials after the entrance meeting has begun. Why? Because, their time is usually fully committed to a prior client during the weeks preceding this engagement. As a result, there is limited time to look at the files that may be provided to them, and most auditors will agree that receiving the files the day they are on site gives them plenty to keep busy. In addition, this also provides more time to ensure that the document request list has been adequately prepared, reviewed, and QA’d prior to providing it to the auditors. The exception to this may be when scripts are requested to be run against infrastructure devices, such as UNIX/Windows Servers, Firewalls, Routers, etc., and the output is needed for the auditors to begin their analysis.

Senior management should be invited to the entrance meeting so that they are aware of the scope and timeline of the audit. All managers that have a role in providing information, attending interviews, or providing staff should also be included. Depending upon the organization, it generally does not hurt to encourage everyone that has a key role in providing information to the auditors to attend as well. The entrance call is scheduled for 30 minutes to 1 hour; however, in practice, the call is normally 10–15 minutes as there is not much to discuss at this point. The scope has been agreed to per prior audit engagement contracts or conversations and should not be a surprise at this juncture. The meeting is more of a formality to kick off the audit project and answer any questions that need to be clarified.

From an organization’s point of view, the audit entrance meeting should not be considered complete if there are still lingering questions regarding (1) audit scope, (2) timing of fieldwork, (3) delivery dates of the draft and final reports (may be approximate), (4) documentation requested, (5) samples that will be requested, and (6) departments that must be involved. The failure to have an understanding of any of these items by this point can lead to unnecessary confusion.

Exit Meeting

An audit may have multiple exit meetings depending on the duration of the audit. If the audit involves on-site fieldwork of several weeks, but the audit itself takes several months to complete, the auditors may hold a site exit meeting to reaffirm the results of their fieldwork, while scheduling a formal exit conference at the end of their analysis and prior to the issuance of the audit report. The purpose of the exit meeting is to signal the end of the audit activities and ensure that both the auditor and auditee come away with the same understanding. These meetings are usually scheduled in late morning or midday on the final day of the audit, again permitting auditor cleanup and travel time in the afternoon.

Status Meetings

Status meetings provide a more frequent opportunity for the auditor and the auditee to ensure that there are no surprises or misunderstandings at the exit conference. Knowing what issues the auditors are facing early in the process provides an opportunity to provide other documentation that may better answer the auditors’ request or permit further dialogue to clarify the control in question. It also provides the opportunity for the audit coordinator to validate that the auditor has received the information requested and that the information provided was satisfactory.

Some organizations prefer a daily status meeting; however, in practice, if the audit coordinator is communicating on a frequent basis with the auditor, a formal meeting every other day should be sufficient. These are scheduled near the end of the normal workday (4:00 or 4:30 p.m.) for 30 minutes so that other management staff can attend. This is true even if the auditors may be working until 6:00 or 7:00 p.m., to ensure the most attendance possible. The meetings should focus on what observations/gaps/findings have been noted or what documentation has been requested and is still outstanding. An agenda and updated document request list should be provided by the auditor in advance of each status update meeting to ensure that the conversation is focused on the important issues.

Setup Interviews

As with the entrance, exit, and status meetings, as many setup interviews as possible should be scheduled prior to the start of the audit. The document request list provides the procedures, reports, samples, and other evidence, but does not have the element of human interaction or an explanation of what is written in the documents. The setup interview provides the auditor with the opportunity to ask clarifying questions of the information provided. This also represents an opportunity to provide an overall big-picture description of a control or management area. For example, the information security manager could provide an overview of access management or security administration and how user IDs and logins are obtained, the business continuity/disaster recovery manager could explain all the activities involved in ensuring continuity of operations, or the human resources manager could explain how a new hire is on boarded into the organization with reference checks, background checks, confidentiality statements, and PeopleSoft human resource/payroll transactions.

Interviews should be scheduled for 1–1.5 hours each with at least 30 minutes in between each interview to permit the auditors a chance to digest what they have heard and subsequently review their notes. They will also need time to prepare for the next interview. Generally, the interviews should be scheduled during the first week of a multiweek audit so that the environment controls and processes are understood by the audit early on in the process. This can avoid sample pulls of the wrong information or invalid assumptions when evaluating the documents provided, leading to rework for both parties. Given these constraints, it is generally advisable to spread the interviews out during the first week, with no more than two scheduled for a morning or an afternoon. Afternoon or morning status meetings will also be scheduled during these days. Given that the first day is a travel day, many auditors will request that no more than one interview is scheduled on the afternoon of the first day, in addition to the entrance meeting. The status meeting is typically not scheduled on the first day, as there is nothing to report. The auditors also prefer this time to begin reviewing the document request list items.

Finally, it is also useful to create a spreadsheet to map the individuals to the date and time of the interview to ensure that there are no availability issues. It should also be noted whether or not that person is required to be physically present for the interview. There is usually more interaction with a face-to-face interview and more rapport is established with the auditor. At a minimum, the primary point of contact should be present in the interview, with the secondary individuals available by phone. The audit coordinator should also be present in the interviews to monitor how the audit is performing as well as to initiate the conference calls, record the attendees, and continuously look for ways to improve the audit process.

Execution Phase

Additional Audit Meetings

With appropriate planning and scheduling, the meetings should flow from the entrance to the exit conference according to the schedule. Additional meetings will have to be scheduled as the auditor reviews the documents requested and performs tests of the audit plan. The security manager is best served by letting the auditor request these additional meetings, as they are only necessary if the auditor is having difficulty interpreting the information provided. In other words, volunteering to set up meetings to walk through every document requested when the auditor has not specifically requested such meetings, only takes away from the valuable audit time that the auditor has to complete the audit. The auditor may have reviewed the information provided and decided that the evidence was sufficient and therefore needed no further explanation.

Establish Auditor Communication Protocol

Messages on the Internet get from person A to person B through a standard communications protocol. Teenage text messages are sent by understanding an agreed-upon set of communications, some of which make us LOL. To be really effective in working with the auditors to ensure that they have the right information, at the right place, and at the right time, we need to establish an effective way of communicating. The failure to do so ends up with the auditor saying things like “I requested that information 5 days ago and haven’t seen it,” possibly evoking the response, “but we sent it to your team 3 times already.” Who is right? At this point, it does not really matter; what matters is that the process of communication failed. At the end of the day, if the auditor does not receive the information requested during the audit time period, they cannot validate that the documented control is in place and working.

To increase the likelihood that the above-mentioned scenario does not occur, the following activities should be agreed upon with the auditor no later than the first day of the audit. A good time to discuss this protocol is after the entrance meeting, between the audit coordinator and the lead auditor and the audit team.

![]() Track every information request from the auditor during the audit in a spreadsheet separate from the auditor document request list.

Track every information request from the auditor during the audit in a spreadsheet separate from the auditor document request list.

![]() Assign a unique number to each information request to enable tracking.

Assign a unique number to each information request to enable tracking.

![]() Ensure during the audit that it is clear which information request referred to is being analyzed by referring to the tracking number.

Ensure during the audit that it is clear which information request referred to is being analyzed by referring to the tracking number.

![]() Implement a scheme (i.e., a, b, c, 0.01, 0.02, 0.03) to track follow-up requests for information already provided. This helps keep the information organized together.

Implement a scheme (i.e., a, b, c, 0.01, 0.02, 0.03) to track follow-up requests for information already provided. This helps keep the information organized together.

![]() Require the auditors to put all requests in writing and assign a number to ensure that it is clear what the auditor is requesting.

Require the auditors to put all requests in writing and assign a number to ensure that it is clear what the auditor is requesting.

![]() Determine the number of times a day that the auditor would like to receive outstanding requests. Limiting the number to once or twice a day, unless there are many requests, increases both auditor and auditee efficiency.

Determine the number of times a day that the auditor would like to receive outstanding requests. Limiting the number to once or twice a day, unless there are many requests, increases both auditor and auditee efficiency.

![]() Require that all incoming and outgoing requests go through the audit coordinator so that they can be tracked.

Require that all incoming and outgoing requests go through the audit coordinator so that they can be tracked.

The net effect of these items is that all information is tracked and its status is immediately known. When the status meetings are held and the auditor and the audit coordinator have tracked the requests, they can be compared to see where the gaps are and reconciled. Accurate tracking by a central person avoids the “he said she said” discussion, as well as creating the impression that the company is working diligently to ensure that the auditor has the information on a timely basis. From an economic perspective, it is just better business to have to request and furnish the information onetime.

Establish Internal Company Protocol

Just as it is important to have a protocol established with the auditors, it is equally important that the following protocol is followed internally:

![]() All audit requests for additional information are sent only from the audit coordinator.

All audit requests for additional information are sent only from the audit coordinator.

![]() All responses to requests for additional information are sent to the auditor from the audit coordinator.

All responses to requests for additional information are sent to the auditor from the audit coordinator.

![]() E-mail subject lines contain the year, audit name, tracking number, and a brief description of the item to permit searching for requests.

E-mail subject lines contain the year, audit name, tracking number, and a brief description of the item to permit searching for requests.

![]() Information is placed in a directory related to the tracking number and a reply to the request from the audit coordinator from the person providing the information indicates that the information is complete and ready to provide to the auditor.

Information is placed in a directory related to the tracking number and a reply to the request from the audit coordinator from the person providing the information indicates that the information is complete and ready to provide to the auditor.

![]() A protocol is established for moving the request from “completed status” to “sent to the auditor” by the audit coordinator.

A protocol is established for moving the request from “completed status” to “sent to the auditor” by the audit coordinator.

![]() Audit requests are expected to be fulfilled within 24 hours (exceptions may be acceptable for items that must be retrieved from off-site or other contractors/outsourced operations).

Audit requests are expected to be fulfilled within 24 hours (exceptions may be acceptable for items that must be retrieved from off-site or other contractors/outsourced operations).

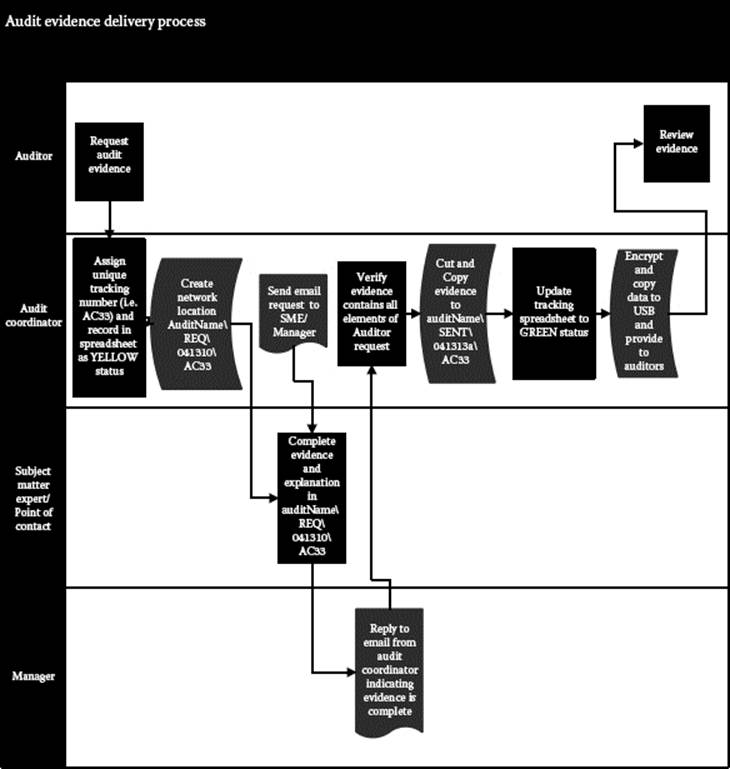

Figure 4.2 shows the flow of information from the initial request through fulfillment. By tracking each request in a spreadsheet and subsequently maintaining a tracking number throughout the process, information is less likely to be lost. As shown in the diagram, when the audit coordinator assigns the request, it is logged in a spreadsheet with a tracking number. The same number, in this case AC33, is used as the folder name under the directory REQ\041313, where 041313 is the date that the item was requested (13 April 2013). Once the audit coordinator receives the e-mail response from the point of contact assigned to fulfill the request in the folder that the information is complete, he proceeds to move the folder to the SENT\(today’s date) folder. He then provides this information to the auditor along with other items that are complete.

Figure 4.2 Flow of information from initial request through fulfillment.

Using this method of SENT and REQ folders (1) provides a mechanism (a place) for the point of contact to place the items requested and (2) provides knowledge that the information was subsequently provided to the auditor. The folder structure also serves as an additional validation of the tracking spreadsheet; i.e., no contents in the REQ folder indicates that the request was completed.

Media Handling

The documents provided for the auditor’s review during the course of an audit contain confidential information that could cause harm if disclosed outside the organization or beyond the audit firm. For this reason, all information provided to the auditors should be encrypted, preferably with a product that is FIPS 140-2 compliant. This greatly reduces the risk that this information will be disclosed during its useful life. Documents such as security plans, baseline configurations, script output, and firewall rules contain highly confidential information.

The media may be passed to the auditors on site by burning the information onto a CD or USB thumb drive. In either case, it is not necessary to encrypt each file individually, but rather each submission to the auditor could be encrypted by encrypting the high-level folder and all subdirectories. For example, if the contents were copied to an\InfoSecAudits\2013\SENT\041910a folder, where “a” is the first submission of the day to the auditors, then this folder could be encrypted and the contents copied to a CD or USB drive.

Establishing a common password for the entire project makes the encryption process much easier and also increases the probability that after the audit, the files will be readable because onetime passwords may not be well documented. The password should be communicated to the team in a separate e-mail. The password should also be constructed as a strong password due to the nature of the audit artifacts that are being collected. A password composed of at least 8 characters (preferably 10), at least one uppercase, one lowercase, one numeric, and one special character, should be sufficient. A password constructed in this way also tends to void the use of pets names, dictionary names, birthdays, etc.

It is not advisable to send the audit artifacts by e-mail, as the average user has a plethora of e-mails on a daily basis and tracking who sent what, when, and to whom becomes a challenge. As mentioned previously, the better approach is to use the e-mail system for the audit coordinator to distribute the requests to the points of contact, requesting that the audit artifacts be placed in the appropriate REQ\Date\ItemTrackingNo on the server for subsequent handling. These can be placed on the server in an unencrypted format, as the audit coordinator will encrypt the entire contents of the SENT\Date+suffix folder when the items are sent. It is also not uncommon for the size of many of these files or file collections to exceed the 10MB range, which is typically a constraint imposed on the e-mails today.

It is to the company’s advantage to provide as much information to the auditors while on site because these files easily fit on 16G/32G/64G USB drives. Once the auditor has left the site, the files may have to be broken into 10MB file sizes or less, the files encrypted, and multiple e-mails sent to the off-site auditors. This situation can be avoided by adequate preparation and confirmation that the auditors have received all the required documents during the status meetings and the site exit meeting. The file size may be so large (>100MB) that it only makes sense to burn this information onto a CD or copy it to a USB and send it via overnight mail. This is not desirable, as there are still delays for the auditor in receiving the information, plus this adds unnecessary expense in having to provide rework.

Audit Coordinator Quality Review

The point of contacts or the subject matter experts who are supplying the information are in the best position to ascertain whether or not they are meeting the audit request, as they are the ones closest to the business process. The audit coordinator still needs to briefly review the information provided to the auditors as a second look to catch errors similar to those previously noted in reviewing the initial document request list. Given that it may take an overnight process to extract the requested information, and the auditors may not review the information provided immediately, it behooves the organization to provide the information requested correctly the first time. The QA process helps ensure completeness of the response.

The Interview Itself

Auditees are expected to answer questions truthfully, and failure to do so may constitute obstruction of a federal audit with the U.S. government-initiated audits, or constitute a company or industry ethics violation. Audits are intended to improve the organization’s control environment and lying or misrepresenting the facts would serve little purpose and would not lead to making needed improvements in processes that would be identified by the audits.

With truthfulness as the foundation for the audit, the auditee respondent should only answer the questions that are asked. Providing details outside the request not only wastes the auditor’s time with “filler fluff” that may be irrelevant to the testing that the auditor is performing, but it may also expose other areas of vulnerability that are beyond the scope of the audit. Some auditors are known for going on fishing expeditions, whereby they may ask, “I have just one more question,” a line made famous by the TV show Columbo in the 1970s and 1980s. This line of questioning is primarily intended to reveal a flaw somewhere within the system by poking around. So why wouldn’t we want to know all the areas where we have issues? The answer is not so much that we don’t want to know, but rather we want to be on a fair-playing field with our competitors. Say, our firm is being audited for PCI compliance by a aualified auditor, or our contractual requirements mandate that an SAS070 be performed to get the business, we would want to be evaluated based upon an audit program that our competitors are being evaluated against. Therefore, it is important that individuals who are selected for interview are able to answer the questions posed by the auditors, but not so verbose that they start talking about unrelated items or bring up other vulnerabilities outside the scope of the audit. Most people are proud of their work and want to talk about it with whoever listens. An audit interview, outside the interview sections where overviews of the processes are provided, is not the time to explain all the details of a process unless requested by the auditor.

Mock interview sessions are advantageous for those individuals who have not been involved in an audit before, as well as a refresher for those who are engaged in them infrequently. In a mock interview, an individual can portray the auditor, asking a series of questions requesting evidence that a control activity was performed. This can help put the interviewee more at ease during the audit. The mock interview may also trigger additional information request ideas that were previously missed, to support the organization’s control position.

Reporting Phase

All control deficiencies should be known and communicated by the exit conference. If, for some reason, testing could not be completed, additional deficiencies could be noted after the auditors have left the site. If this is the case, for reasons mentioned in the Media Handling section, this complicates the audit and should be avoided. Proactive inquiry of the auditors to ensure that they have all the necessary information, especially by the start of the final week of the audit, should be done. The auditors should be focused on completing their workpapers in the final week of the audit versus performing additional testing. This usually occurs because of a disagreement in earlier testing or the selection of a new sample that was deemed insufficient (i.e., population was assumed to be both employees and contractors, but only employees were provided).

At the exit conference, the auditor should provide a listing of the control deficiencies (also referred to as gaps, observations, exceptions, findings, depending upon the nomenclature used by the auditor). These may or may not end up as findings on the final report. The auditors may have to evaluate the findings with other organizations that have been included in the scope of the audit. For example, for a chief financial officer’s (CFO’s) audit contracted by the federal government, the audit firm may wait until they have been to all the sites to ensure that they have been consistent in their approach and fair to each contractor. Another reason for not receiving the findings at the exit conference is that further peer reviews may need to be performed, or the senior partners may need to review the workpapers containing the audit testing and evidence collected.

A draft report is subsequently issued with the findings. There should be no surprises if the audit team and the organization have worked together. Usually, when surprises end up on the report, it is the result of (1) a lack of clear communication in the beginning as to what conditions would create a finding, (2) a prior issue surfaced but was not communicated that it was a finding, (3) documents requested were not provided, (4) misunderstanding whether or not an earlier agreement was reached when discussing a gap, or (5) the auditor held the issue to the end to avoid confrontation. Based on experience of many audits, item (5) does occur, but usually one of the other items is the primary reason for surprises. Surprises should be left for birthdays and holidays and not audit findings!

Once the draft report is received by the organization from the auditor, the auditee has 5–10 business days to provide a response. The response provides the auditee with an opportunity to agree or disagree with the audit finding and explain why. These comments are included in the reissued draft report, which should be issued 5–10 days after receipt of the auditee’s comments. If the organization agrees with the finding, it is best to also note a corrective action plan (CAP) at this time. The CAP explains at a high level what will be done to mitigate the deficiency and when this will be completed. The CAP will need to be submitted within 30 days after the final report is reissued with the auditee comments, so if there is agreement, this may as well be included in the draft report. This provides the reader who is not so familiar with the audit, with an early understanding of the steps that will be taken.

The final report issuance varies by audit firm and the contractual requirements. An internal review of the draft report and the workpapers adds off-site time after the fieldwork to ensure that the audit report is accurate. Sometimes, this process can take months between the issuance of the draft and the final report. Firms that are security conscious will not wait for the final report to begin taking action on the issues. CAPs are typically due within 30 days after the final report issuance, and it is preferable to mitigate the vulnerability within 90 days from the CAP due date. Obviously, long security implementations will be the exception, but should not be the rule. Ninety days should be sufficient to mitigate most vulnerabilities, given the appropriate priority. Each of the CAPs should be tracked to ensure that the person responsible is completing the milestones and that the target date is still on track. As the CAPs are completed, the audit artifacts, including changed processes, reports, project plans, and evidence of implementation, should be retained to provide to the auditor for next year’s review. The auditor will then take these items and use them as partial evidence to close the finding.

About the Author

Todd Fitzgerald, CISSP, CISA, CISM, CGEIT, PMP, HITRUST, ISO27000, ITILV3, National Government Services (WellPoint, Inc. Affiliate), is responsible for external technical audit and internal security compliance for one of the largest processors of Medicare claims. He has led the development of several security programs and actively serves as an international speaker and author of information security issues. He coauthored the 2008 ISC2 book entitled CISO Leadership: Essential Principles for Success. He graduated from the University of Wisconsin–La Crosse, serves as an advisor to the College of Business Administration, and holds an MBA with highest honors from Oklahoma State University.