The Basics of Web Hacking: Tools and Techniques to Attack the Web (2013)

Chapter 1. The Basics of Web Hacking

Chapter Rundown:

■ What you need to know about web servers and the HTTP protocol

■ The Basics of Web Hacking: our approach

■ Common web vulnerabilities: they are still owning us

■ Setting up a safe test environment so you don’t go to jail

Introduction

There is a lot of ground to cover before you start to look at specific tools and how to configure and execute them to best suit your desires to exploit web applications. This chapter covers all the areas you need to be comfortable with before we get into these tools and techniques of web hacking. In order to have the strong foundation you will need for many years of happy hacking, these are core fundamentals you need to fully understand and comprehend. These fundamentals include material related to the most common vulnerabilities that continue to plague the web even though some of them have been around for what seems like forever. Some of the most damaging web application vulnerabilities “in the wild” are still as widespread and just as damaging over 10 years after being discovered.

It’s also important to understand the time and place for appropriate and ethnical use of the tools and techniques you will learn in the chapters that follow. As one of my friends and colleagues likes to say about using hacking tools, “it’s all fun and games until the FBI shows up!” This chapter includes step-by-step guidance on preparing a sandbox (isolated environment) all of your own to provide a safe haven for your web hacking experiments.

As security moved more to the forefront of technology management, the overall security of our servers, networks, and services has greatly improved. This is in large part because of improved products such as firewalls and intrusion detection systems that secure the network layer. However, these devices do little to protect the web application and the data that are used by the web application. As a result, hackers shifted to attacking the web applications that directly interacted with all the internal systems, such as database servers, that were now being protected by firewalls and other network devices.

In the past handful of years, more emphasis has been placed on secure software development and, as a result, today’s web applications are much more secure than previous versions. There has been a strong push to include security earlier in the software development life cycle and to formalize the specification of security requirements in a standardized way. There has also been a huge increase in the organization of several community groups dedicated to application security, such as the Open Web Application Security Project. There are still blatantly vulnerable web applications in the wild, mainly because programmers are more concerned about functionality than security, but the days of easily exploiting seemingly every web application are over.

Therefore, because the security of the web application has also improved just like the network, the attack surface has again shifted; this time toward attacking web users. There is very little that network administrators and web programmers can do to protect web users against these user-on-user attacks that are now so prevalent. Imagine a hacker’s joy when he can now take aim on an unsuspecting technology-challenged user without having to worry about intrusion detection systems or web application logging and web application firewalls. Attackers are now focusing directly on the web users and effectively bypassing any and all safeguards developed in the last 10 + years for networks and web applications.

However, there are still plenty of existing viable attacks directed at web servers and web applications in addition to the attacks targeting web users. This book will cover how all of these attacks exploit the targeted web server, web application, and web user. You will fully understand how these attacks are conducted and what tools are needed to get the job done. Let’s do this!

What Is a Web Application?

The term “web application” has different meanings to different people. Depending on whom you talk to and the context, different people will throw around terms like web application, web site, web-based system, web-based software or simply Web and all may have the same meaning. The widespread adoption of web applications actually makes it hard to clearly differentiate them from previous generation web sites that did nothing but serve up static, noninteractive HTML pages. The term web application will be used throughout the book for any web-based software that performs actions (functionality) based on user input and usually interacts with backend systems. When a user interacts with a web site to perform some action, such as logging in or shopping or banking, it’s a web application.

Relying on web applications for virtually everything we do creates a huge attack surface (potential entry points) for web hackers. Throw in the fact that web applications are custom coded by a human programmer, thus increasing the likelihood of errors because despite the best of intentions. Humans get bored, hungry, tired, hung-over, or otherwise distracted and that can introduce bugs into the web application being developed. This is a perfect storm for hackers to exploit these web applications that we rely on so heavily.

One might assume that a web application vulnerability is merely a human error that can be quickly fixed by a programmer. Nothing could be further from the truth: most vulnerabilities aren’t easily fixed because many web application flaws dates back to early phases of the software development lifecycle. In an effort to spare you the gory details of software engineering methodologies, just realize that security is much easier to deal with (and much more cost effective) when considered initially in the planning and requirements phases of software development. Security should continue as a driving force of the project all the way through design, construction, implementation, and testing.

But alas, security is often treated as an afterthought too much of the time; this type of development leaves the freshly created web applications ripe with vulnerabilities that can be identified and exploited for a hacker’s own nefarious reasons.

What You Need to Know About Web Servers

A web server is just a piece of software running on the operating system of a server that allows connections to access a web application. The most common web servers are Internet Information Services (IIS) on a Windows server and Apache Hypertext Transfer Protocol (HTTP) Server on a Linux server. These servers have normal directory structures like any other computer, and it’s these directories that house the web application.

If you follow the Windows next, next, next, finish approach to installing an IIS web server, you will end up with the default C:\Inetpub\wwwroot directory structure where each application will have its own directories within wwwroot and all vital web application resources are contained within it.

Linux is more varied in the file structure, but most web applications are housed in the /var/www/ directory. There are several other directories on a Linux web server that are especially relevant to web hacking:

■ /etc/shadow: This is where the password hashes for all users of the system reside. This is the “keys to the kingdom”!

■ /usr/lib: This directory includes object files and internal binaries that are not intended to be executed by users or shell scripts. All dependency data used by the application will also reside in this directory. Although there is nothing executable here, you can really ruin somebody’s day by deleting all of the dependency files for an application.

■ /var/*: This directory includes the files for databases, system logs, and the source code for web application itself!

■ /bin: This directory contains programs that the system needs to operate, such as the shells, ls, grep, and other essential and important binaries. bin is short for binary. Most standard operating system commands are located here as separate executable binary files.

The web server is a target for attacks itself because it offers open ports and access to potentially vulnerable versions of web server software installed, vulnerable versions of other software installed, and misconfigurations of the operating system that it’s running on.

What You Need to Know About HTTP

The HTTP is the agreed upon process to interact and communicate with a web application. It is completely plaintext protocol, so there is no assumption of security or privacy when using HTTP. HTTP is actually a stateless protocol, so every client request and web application response is a brand new, independent event without knowledge of any previous requests. However, it’s critical that the web application keeps track of client requests so you can complete multistep transactions, such as online shopping where you add items to your shopping cart, select a shipping method, and enter payment information.

HTTP without the use of cookies would require you to relogin during each of those steps. That is just not realistic, so the concept of a session was created where the application keeps track of your requests after you login. Although sessions are a great way to increase the user-friendliness of a web application, they also provide another attack vector for web applications. HTTP was not originally created to handle the type of web transactions that requires a high degree of security and privacy. You can inspect all the gory details of how HTTP operates with tools such as Wireshark or any local HTTP proxy.

The usage of secure HTTP (HTTPS) does little to stop the types of attacks that will be covered in this book. HTTPS is achieved when HTTP is layered on top of the Secure Socket Layer/Transport Layer Security (SSL/TLS) protocol, which adds the TLS of SSL/TLS to normal HTTP request and responses. It is best suited for ensuring man-in-the-middle and other eavesdropping attacks are not successful; it ensures a “private call” between your browser and the web application as opposed to having a conversation in a crowded room where anybody can hear your secrets. However, in our usage, HTTPS just means we are going to be communicating with the web application over an encrypted communication channel to make it a private conversation. The bidirectional encryption of HTTPS will not stop our attacks from being processed by the waiting web application.

HTTP Cycles

One of the most important fundamental operations of every web application is the cycle of requests made by clients’ browsers and the responses returned by the web server. It’s a very simple premise that happens many of times every day. A browser sends a request filled with parameters (variables) holding user input and the web server sends a response that is dictated by the submitted request. The web application may act based on the values of the parameters, so they are prime targets for hackers to attack with malicious parameter values to exploit the web application and web server.

Noteworthy HTTP Headers

Each HTTP cycle also includes headers in both the client request and the server response that transmit details about the request or response. There are several of these headers, but we are only concerned with a few that are most applicable to our approach covered in this book.

The headers that we are concerned about that are set by the web server and sent to the client’s browser as part of the response cycle are:

■ Set-Cookie: This header most commonly provides the session identifier (cookie) to the client to ensure the user’s session stays current. If a hacker can steal a user’s session (by leveraging attacks covered in later chapters), they can assume the identity of the exploited user within the application.

■ Content-Length: This header’s value is the length of the response body in bytes. This header is helpful to hackers because you can look for variation in the number of bytes of the response to help decipher the application’s response to input. This is especially applicable when conducting brute force (repetitive guessing) attacks.

■ Location: This header is used when an application redirects a user to a new page. This is helpful to a hacker because it can be used to help identify pages that are only allowed after successfully authenticating to the application, for example.

The headers that you should know more about that are sent by the client’s browser as part of the web request are:

■ Cookie: This header sends the cookie (or several cookies) back to the server to maintain the user’s session. This cookie header value should always match the value of the set-cookie header that was issued by the server. This header is helpful to hackers because it may provide a valid session with the application that can be used in attacks against other application users. Other cookies are not as juicy, such as a cookie that sets your desired language as English.

■ Referrer: This header lists the webpage that the user was previously on when the next web request was made. Think of this header as storing the “the last page visited.” This is helpful to hackers because this value can be easily changed. Thus, if the application is relying on this header for any sense of security, it can easily be bypassed with a forged value.

Noteworthy HTTP Status Codes

As web server responses are received by your browser, they will include a status code to signal what type of response it is. There are over 50 numerical HTTP response codes grouped into five families that provide similar type of status codes. Knowing what each type of response family represents allows you to gain an understanding of how your input was processed by the application.

■ 100s: These responses are purely informational from the web server and usually mean that additional responses from the web server are forthcoming. These are rarely seen in modern web server responses and are usually followed close after with another type of response introduced below.

■ 200s: These responses signal the client’s request was successfully accepted and processed by the web server and the response has been sent back to your browser. The most common HTTP status code is 200 OK.

■ 300s: These responses are used to signal redirection where additional responses will be sent to the client. The most common implementation of this is to redirect a user’s browser to a secure homepage after successfully authenticating to the web application. This would actually be a 302 Redirect to send another response that would be delivered with a 200 OK.

■ 400s: These responses are used to signal an error in the request from the client. This means the user has sent a request that can’t be processed by the web application, thus one of these common status codes is returned: 401 Unauthorized, 403 Forbidden, and 404 Not Found.

■ 500s: These responses are used to signal an error on the server side. The most common status codes used in this family are the 500 Internal Server Error and 503 Service Unavailable.

Full details on all of the HTTP status codes can be reviewed in greater detail at http://www.w3.org/Protocols/rfc2616/rfc2616-sec10.html.

The Basics of Web Hacking: Our Approach

Our approach is made up of four phases that cover all the necessary tasks during an attack.

1. Reconnaissance

2. Scanning

3. Exploitation

4. Fix

It’s appropriate to introduce and discuss how these vulnerabilities and attacks can be mitigated, thus there is a fix phase to our approach. As a penetration tester or ethical hacker, you will get several questions after the fact related to how the discovered vulnerabilities can be fixed. Consider the inclusion of the fix phase to be a resource to help answer those questions.

Our Targets

Our approach targets three separate, yet related attack vectors: the web server, the web application, and the web user. For the purpose of this book, we will define each of these attack vectors as follows:

1. Web server: the application running on an operating system that is hosting the web application. We are NOT talking about traditional computer hardware here, but rather the services running on open ports that allow a web application to be reached by users’ internet browsers. The web server may be vulnerable to network hacking attempts targeting these services in order to gain unauthorized access to the web server’s file structure and system files.

2. Web application: the actual source code running on the web server that provides the functionality that web users interact with is the most popular target for web hackers. The web application may be susceptible to a vast collection of attacks that attempt to perform unauthorized actions within the web application.

3. Web user: the internal users that manage the web application (administrators and programmers) and the external users (human clients or customers) of the web applications are worthy targets of attacks. This is where a cross-site scripting (XSS) or cross-site request forgery (CSRF) vulnerabilities in the web application rear their ugly heads. Technical social engineering attacks that target web users and rely on no existing web application vulnerabilities are also applicable here.

The vulnerabilities, exploits, and payloads are unique for each of these targets, so unique tools and techniques are needed to efficiently attack each of them.

Our Tools

For every tool used in this book, there are probably five other tools that can do the same job. (The same goes for methods, too.) We’ll emphasize the tools that are the most applicable to beginner web hackers. We recommend these tools not because they’re easy for beginners to use, but because they’re fundamental tools that virtually every professional penetration tester uses on a regular basis. It’s paramount that you learn to use them from the very first day. Some of the tools that we’ll be using include:

■ Burp Suite, which includes a host of top-notch web hacking tools, is a must-have for any web hacker and it’s widely accepted as the #1 web hacking tool collection.

■ Zed Attack Proxy (ZAP) is similar to Burp Suite, but also includes a free vulnerability scanner that’s applicable to web applications.

■ Network hacking tools such as Nmap for port scanning, Nessus and Nikto for vulnerability scanning, and Metasploit for exploitation of the web server.

■ And other tools that fill a specific role such as sqlmap for SQL injection, John the Ripper (JtR) for offline password cracking, and the Social Engineering Toolkit (SET) for technical social engineering attacks against web users!

Web Apps Touch Every Part of IT

Another exciting tidbit for web hackers is the fact that web applications interact with virtually every core system in a company’s infrastructure. It’s commonplace to think that the web application is just some code running on a web server safely tucked away in an external DMZ incapable of doing serious internal damage to a company. There are several additional areas of a traditional IT infrastructure that need to be considered in order to fully target a system for attack, because a web application’s reach is much wider than the code written by a programmer. The following components also need to be considered as possible attack vectors:

■ Database server and database: the system that is hosting the database that the web application uses may be vulnerable to attacks that allow sensitive data to be created, read, updated, or deleted (CRUD).

■ File server: the system, often times a mapped drive on a web server, that allows file upload and/or download functionality may be vulnerable to attacks that allow server resources to be accessed from an unauthorized attacker.

■ Third-party, off-the-shelf components: modules of code, such as content management systems (CMSs), are a definitely a target because of the widespread adoption and available documentation of these systems.

Existing Methodologies

Several attack methodologies provide the processes, steps, tools, and techniques that are deemed to be best practices. If you’re a white hat hacker, such activities are called penetration testing (pen test for short or PT for even shorter), but we all realize they are the same activities as black hat hacking. The two most widely accepted pen test methodologies today are the Open-Source Security Testing Methodology Manual (OSSTM) and the Penetration Testing Execution Standard (PTES).

The Open-Source Security Testing Methodology Manual (OSSTM)

The OSSTM was created in a peer review process that created cases that test five sections:

1. Information and data controls

2. Personnel security awareness levels

3. Fraud and social engineering levels

4. Computer and telecommunications networks, wireless devices, and mobile devices

5. Physical security access controls, security process, and physical locations

The OSSTM measures the technical details of each of these areas and provides guidance on what to do before, during, and after a security assessment. More information on the OSSTM can be found at the project homepage athttp://www.isecom.org/research/osstmm.html.

Penetration Testing Execution Standard (PTES)

The new kid on the block is definitely the PTES, which is a new standard aimed at providing common language for all penetration testers and security assessment professionals to follow. PTES provides a client with a baseline of their own security posture, so they are in a better position to make sense of penetration testing findings. PTES is designed as a minimum that needs to be completed as part of a comprehensive penetration test. The standard contains many different levels of services that should be part of advanced penetration tests. More information can be found on the PTES homepage at http://www.pentest-standard.org/.

Making Sense Of Existing Methodologies

Because of the detailed processes, those standards are quite daunting to digest as a beginning hacker. Both of those standards basically cover every possible aspect of security testing, and they do a great job. Tons of very smart and talented people have dedicated countless hours to create standards for penetration testers and hackers to follow. Their efforts are certainly commendable, but for beginning hackers it’s sensory overload. How are you going to consider hacking a wireless network when you may not even understand basic network hacking to begin with? How are you going to hack a mobile device that accesses a mobile version of a web application when you may not be comfortable with how dynamic web applications extract and use data from a database?

What is needed is to boil down all the great information in standards such as the OSSTM and PTES into a more manageable methodology so that beginning hackers aren’t overwhelmed. That’s the exact goal of this book. To give you the necessary guidance to get you started with the theory, tools, and techniques of web hacking!

Most Common Web Vulnerabilities

Our targets will all be exploited by attacking well-understood vulnerabilities. Although there are several other web-related vulnerabilities, these are the ones we are going to concentrate on as we work through the chapters.

Injection

Injection flaws occur when untrusted user data are sent to the web application as part of a command or query. The attacker’s hostile data can trick the web application into executing unintended commands or accessing unauthorized data. Injection occurs when a hacker feeds malicious, input into the web application that is then acted on (processed) in an unsafe manner. This is one of the oldest attacks against web applications, but it’s still the king of the vulnerabilities because it is still widespread and very damaging.

Injection vulnerabilities can pop up in all sorts of places within the web application that allow the user to provide malicious input. Some of the most common injection attacks target the following functionality:

■ Structured query language (SQL) queries

■ Lightweight directory access protocol (LDAP) queries

■ XML path language (XPATH) queries

■ Operating system (OS) commands

Anytime that the user’s input is accepted by the web application and processed without the appropriate sanitization, injection may occur. This means that the hacker can influence how the web application’s queries and commands are constructed and what data should be included in the results. This is a very powerful exploit!

Cross-Site Scripting (XSS)

Cross-Site Scripting (XSS) occurs when user input is accepted by the application as part of a request and then is used in the output of the response without proper output encoding in place for validation and sanitization. XSS allows attackers to execute scripts in the victim’s browser, which can hijack user sessions, act as a key logger, redirect the user to malicious sites, or anything else a hacker can dream up! A hacker can inject malicious script (often times JavaScript, but it also could be VBScript) that is then rendered in the browser of the victim. Because this script is part of the response from the application, the victim’s browser trusts it and allows the script to run.

XSS comes in two primary “flavors”: reflected and stored. Reflected XSS is much more widespread in web applications and is considered to be less harmful. The reason that reflected XSS is considered less harmful isn’t because of what it can do, but because it’s a one-time attack where the payload sent in a reflected XSS attack is only valid on that one request. Think of reflected XSS as “whoever clicks it, gets it.” Whatever user clicks the link that contains the malicious script will be the only person directly affected by this attack. It is generally a 1:1 hacker to victim ratio. The hacker may send out the same malicious URL to millions of potential victims, but only the ones that click his link are going to be affected and there’s no connection between compromised users.

Stored XSS is harder to find in web applications, but it’s much more damaging because it persists across multiple requests and can exploit numerous users with one attack. This occurs when a hacker is able to inject the malicious script into the application and have it be available to all visiting users. It may be placed in a database that is used to populate a webpage or in a user forum that displays messages or any other mechanism that stores input. As legitimate users request the page, the XSS exploit will run in each of their browsers. This is a 1:many hacker to victim ratio.

Both flavors of XSS have the same payloads; they are just delivered in different ways.

Broken Authentication And Session Management

Sessions are the unique identifiers that are assigned to users after authenticating and have many vulnerabilities or attacks associated with how these identifiers are used by the web application. Sessions are also a key component of hacking the web user.

Application functions related to authentication and session management are often not implemented correctly, allowing attackers to compromise passwords, keys, session tokens, or exploit other implementation flaws to assume other users’ identities. Functionality of the web application that is under the authentication umbrella also includes password reset, password change, and account recovery to name a few.

A web application uses session management to keep track of each user’s requests. Without session management, you would have to log-in after every request you make. Imagine logging in after you search for a product, then again when you want to add it to your shopping cart, then again when you want to check out, and then yet again when you want to supply your payment information. So session management was created so users would only have to login once per visit and the web application would remember what user has added what products to the shopping cart. The bad news is that authentication and session management are afterthoughts compared to the original Internet. There was no need for authentication and session management when there was no shopping or bill paying. So the Internet as we currently know it has been twisted and contorted to make use of authentication and session management.

Cross-Site Request Forgery

CSRF occurs when a hacker is able to send a well-crafted, yet malicious, request to an authenticated user that includes the necessary parameters (variables) to complete a valid application request without the victim (user) ever realizing it.

This is similar to reflected XSS in that the hacker must coerce the victim to perform some action on the web application. Malicious script may still run in the victim’s browser, but CSRF may also perform a valid request made to the web application. Some results of CSRF are changing a password, creating a new user, or creating web application content via a CMS. As long as the hacker knows exactly what parameters are necessary to complete the request and the victim is authenticated to the application, the request will execute as if the user made it knowingly.

Security Misconfiguration

This vulnerability category specifically deals with the security (or lack thereof) of the entire application stack. For those not familiar with the term “application stack,” it refers to operating system, web server, and database management systems that run and are accessed by the actual web application code. The risk becomes even more problematic when security hardening practices aren’t followed to best protect the web server from unauthorized access. Examples of vulnerabilities that can plague the web server include:

■ Out-of-date or unnecessary software

■ Unnecessary services enabled

■ Insecure account policies

■ Verbose error messages

Effective security requires having a secure configuration defined and deployed for the application, frameworks, application server, web server, database server, and operating system. All these settings should be defined, implemented, and maintained, as many are not shipped with secure defaults. This includes keeping all software up to date, including all code libraries used by the application.

Setting Up a Test Environment

Before you dig into the tools and techniques covered in the book, it’s important that you set up a safe environment to use. Because this is an introductory hands-on book, we’ll practice all the techniques we cover on a vulnerable web application. There are three main requirements you need to consider when setting up a testing environment as you work through the book.

1. Because you will be hosting this vulnerable web application on your own computer, it’s critical that we configure it in a way that does not open your computer up for attack.

2. You will be using hacking tools that are not authorized outside of your personal use, so it’s just as critical to have an environment that does not allow these tools to inadvertently escape.

3. You will surely “break” the web application or web server as you work your way through the book, so it’s critical that you have an environment that you can easily set up initially as well as “push the reset button” to get back to a state where you know everything is set up correctly.

There are countless ways that you could set up and configure such an environment, but for the duration of this book, virtual machines will be used. A virtual machine (VM), when configured correctly, meets all three of our testing environment requirements. A VM is simply a software implementation of a computing environment running on another computer (host). The VM makes requests for resources, such as processing cycles and RAM memory usage, to the host computer that allows the VM to behave in the same manner as traditionally installed operating systems. However, a VM can be turned off, moved, restored, rolled back, and deleted very easily in a matter of just a few keystrokes or mouse clicks. You can also run several different VMs at the same time, which allows you to create a virtualized network of VMs all running on your one host computer. These factors make a virtualized testing environment the clear choice for us.

Although you have plenty of options when it comes to virtualization software, in this book we’ll use the popular VMWare Player, available for free at http://www.vmware.com. Owing to its popularity, there are many preconfigured virtual machines that we can use. Having systems already in place saves time during setup and allows you to get into the actual web hacking material sooner and with less hassle.

If VMWare Player is not your preferred solution, feel free to use any virtualization product that you are comfortable with. The exact vendor and product isn’t as important as the ability to set up, configure, and run the necessary virtualized systems.

In this book, we’ll work in one virtual machine that will be used both to host the vulnerable web application (target) and to house all of our hacking tools (attacker). BackTrack will be used for this virtual machine and is available for download at the BackTrack Linux homepage, located at http://www.backtrack-linux.org/downloads/.

Today, BackTrack is widely accepted as the premiere security-oriented operating system. There are always efforts to update and improve the hacker’s testing environment and the recent release of Kali Linux is sure to gain widespread popularity. However, we will be sticking to BackTrack throughout the book. BackTrack includes hundreds of professional-grade tools for hacking, doing reconnaissance, digital forensics, fuzzing, bug hunting, exploitation, and many other hacking techniques. The necessary tools and commands in BackTrack applicable to our approach will be covered in great detail as they are introduced.

Target Web Application

Damn Vulnerable Web Application (DVWA) will be used for the target web application and can be researched further at its homepage at http://www.dvwa.co.uk/. DVWA is a PHP/MySQL web application that is vulnerable by design to aid security professionals as they test their skills and tools in a safe and legal environment. It’s also used to help web developers better understand the processes of securing web applications.

However, DVWA is not natively available as a VM, so you would have to create your own VM and then set up and configure DVWA to run inside this new VM. If that interests you, installation instructions and the files necessary to download are available on the DVWA web site.

For our purposes, we will be accessing DVWA by having it run locally in the BackTrack VM via http://localhost or the 127.0.0.1 IP address. We will be hosting both our target application (DVWA) and the hacking tools in our BackTrack VM. This means you will have everything you need in one VM and will use less system resources.

Installing The Target Web Application

In order to set up our safe hacking environment, we first need to download a BackTrack VM and configure it to host the DVWA target web application. The following steps ready the BackTrack VM for installation of the DVWA.

1. Download a BackTrack virtual machine from http://www.backtrack-linux.org/downloads/.

2. Extract the. 7z file of the BackTrack virtual machine.

3. Launch the BackTrack VM by double-clicking the .vmx file in the BackTrack folder. If prompted, select I copied it and select OK.

4. Login to BackTrack with the root user and toor password.

5. Use the startx command to start the graphical user interface (GUI) of BackTrack.

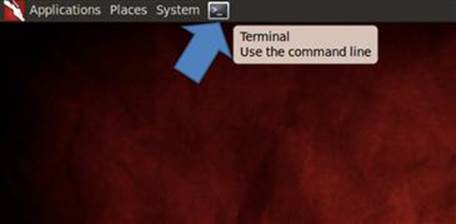

6. Open a terminal by clicking on the Terminal icon in the upper left-hand corner of the screen. It’s the one that looks like a computer screen with > _ on it as shown in Figure 1.1. This is where we will be entering commands (instructions) for a myriad of BackTrack tools!

FIGURE 1.1 Opening a terminal in BackTrack.

Once you have successfully logged into BackTrack, complete the following steps to install DVWA as the target application. This will require a live Internet connection, so ensure that your host machine can browse the Internet by opening a Firefox browser to test connectivity.

Alert

For trouble-shooting your VM’s ability to make use of the host machine’s Internet connection, check the network adapter settings for your VM in VM Player if necessary. We are using the NAT network setting.

1. Browse to http://theunl33t.blogspot.com/2011/08/script-to-download-configure-and-launch.html in Firefox (by clicking on Applications and then Internet) in your BackTrack VM to view the DVWA installation script created by the team at The Unl33t. A link to this script is also included later in the chapter for your reference.

2. Select and copy the entire script starting with #/bin/bash and ending with last line that ends with DVWA Install Finished!\n.

3. Open gedit Text Editor in BackTrack by clicking on Applications and then Accessories.

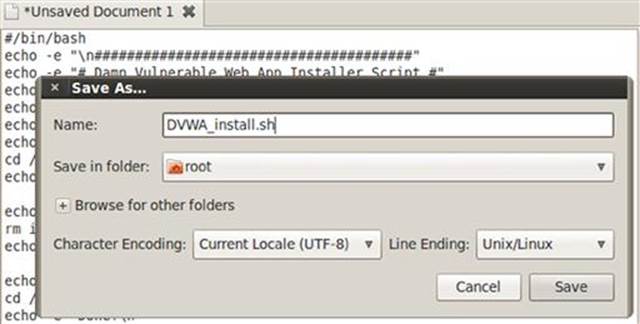

4. Paste the script and save the file as DVWA_install.sh in the root directory as shown in Figure 1.2.

FIGURE 1.2 Saving the DVWA install script in the root directory.

5. Close gedit and Firefox.

6. Open a terminal and run the ls command to verify the script is in the root directory.

7. Execute the install script by running the sh DVWA_install.sh command in a terminal. The progress of the installation will be shown in the terminal and a browser window to the DVWA login page will launch when successfully completed.

Configuring The Target Web Application

Once DVWA is successfully installed, complete the following steps to login and customize the web application:

1. Login to DVWA with the admin username and password password as shown in Figure 1.3.

FIGURE 1.3 Logging into DVWA as an application administrator.

Alert

The URL is 127.0.0.1 (this is localhost; the web server running directly in BackTrack).

2. Click the options button in the lower right of Firefox if you are prompted about a potentially malicious script. Remember DVWA is purposely vulnerable, so we need to allow scripts to run.

3. Click Allow 127.0.0.1 so scripts are allowed to run on our local web server.

4. Click the Setup link in DVWA.

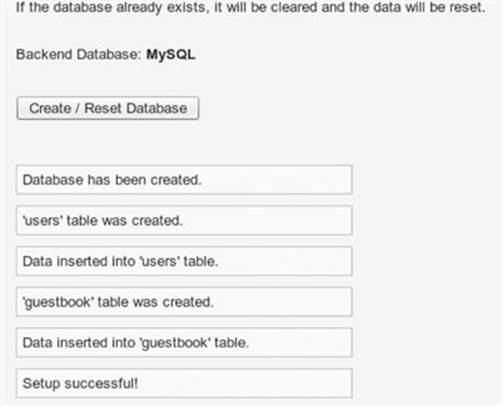

5. Click the Create / Setup Database button to create the initial database to be used for our exercises as shown in Figure 1.4.

FIGURE 1.4 Confirmation that the initial database setup completed successfully.

6. Click the DVWA Security link in DVWA and choose low in the drop-down list as shown in Figure 1.5.

FIGURE 1.5 Confirmation that the initial difficulty setup completed successfully.

7. Click the submit button to create these initial difficulty settings to be used for our exercises. If the exercises are too easy for you, feel free to select a more advanced difficulty level!

You are now ready to use hacking tools in BackTrack to attack the DVWA web application. You can revisit any of these steps to confirm that your environment is set up correctly. It is not necessary to shut down the VM every time you want to take a break. Instead, you can suspend the VM, so the state of your work stays intact. If you choose to shut down the VM to conserve system resources (or for any other reason), you can easily follow the steps above to prepare your VM. It’s probably worth noting that you are now running an intentionally vulnerable and exploitable web application on your BackTrack machine. So it’s probably not a good idea to use this machine while connected to the Internet where others could attack you!

DVWA Install Script

#/bin/bash

echo -e "\n#######################################"

echo -e "# Damn Vulnerable Web App Installer Script #"

echo -e "#######################################"

echo " Coded By: Travis Phillips"

echo " Website: http://theunl33t.blogspot.com"

echo -e -n "\n[*] Changing directory to /var/www..."

cd /var/www > /dev/null

echo -e "Done!\n"

echo -n "[*] Removing default index.html..."

rm index.html > /dev/null

echo -e "Done!\n"

echo -n "[*] Changing to Temp Directory..."

cd /tmp

echo -e "Done!\n"

echo "[*] Downloading DVWA..."

wget http://dvwa.googlecode.com/files/DVWA-1.0.7.zip

echo -e "Done!\n"

echo -n "[*] Unzipping DVWA..."

unzip DVWA-1.0.7.zip > /dev/null

echo -e "Done!\n"

echo -n "[*] Deleting the zip file..."

rm DVWA-1.0.7.zip > /dev/null

echo -e "Done!\n"

echo -n "[*] Copying dvwa to root of Web Directory..."

cp -R dvwa/* /var/www > /dev/null

echo -e "Done!\n"

echo -n "[*] Clearing Temp Directory..."

rm -R dvwa > /dev/null

echo -e "Done!\n"

echo -n "[*] Enabling Remote include in php.ini..."

cp /etc/php5/apache2/php.ini /etc/php5/apache2/php.ini1

sed -e 's/allow_url_include = Off/allow_url_include = On/' /etc/php5/apache2/php.ini1 > /etc/php5/apache2/php.ini

rm /etc/php5/apache2/php.ini1 echo -e "Done!\n"

echo -n "[*] Enabling write permissions to /var/www/hackable/upload..."

chmod 777 /var/www/hackable/uploads/

echo -e "Done!\n"

echo -n "[*] Starting Web Service..."

service apache2 start &> /dev/null

echo -e "Done!\n"

echo -n "[*] Starting MySQL..."

service mysql start &> /dev/null

echo -e "Done!\n"

echo -n "[*] Updating Config File..."

cp /var/www/config/config.inc.php /var/www/config/config.inc.php1

sed -e 's/'\'\''/'\''toor'\''/' /var/www/config/config.inc.php1 > /var/www/config/config.inc.php

rm /var/www/config/config.inc.php1

echo -e "Done!\n"

echo -n "[*] Updating Database..."

wget --post-data "create_db=Create / Reset Database" http://127.0.0.1/setup.php&> /dev/null

mysql -u root --password='toor' -e 'update dvwa.users set avatar = "/hackable/users/gordonb.jpg" where user = "gordonb";'

mysql -u root --password='toor' -e 'update dvwa.users set avatar = "/hackable/users/smithy.jpg" where user = "smithy";'

mysql -u root --password='toor' -e 'update dvwa.users set avatar = "/hackable/users/admin.jpg" where user = "admin";'

mysql -u root --password='toor' -e 'update dvwa.users set avatar = "/hackable/users/pablo.jpg" where user = "pablo";'

mysql -u root --password='toor' -e 'update dvwa.users set avatar = "/hackable/users/1337.jpg" where user = "1337";'

echo -e "Done!\n"

echo -e -n "[*] Starting Firefox to DVWA\nUserName: admin\nPassword: password"

firefox http://127.0.0.1/login.php &> /dev/null &

echo -e "\nDone!\n"

echo -e "[\033[1;32m*\033[1;37m] DVWA Install Finished!\n"

All materials on the site are licensed Creative Commons Attribution-Sharealike 3.0 Unported CC BY-SA 3.0 & GNU Free Documentation License (GFDL)

If you are the copyright holder of any material contained on our site and intend to remove it, please contact our site administrator for approval.

© 2016-2026 All site design rights belong to S.Y.A.