QuickBooks 2014: The Missing Manual (2014)

Part II. Bookkeeping

Chapter 16. Making Journal Entries

Most of the time, you don’t need to know double-entry accounting (Accounting Basics: The Important Stuff) to use QuickBooks. When you write checks, receive payments, and perform many other tasks in QuickBooks, the program creates transactions that unobtrusively handle the double-entry accounting for you. But every once in a while, these transactions can’t help, and your only choice is moving money around directly between accounts.

In the accounting world, these direct manipulations are known as journal entries. For example, if you posted income to your only income account but have since decided that you need several income accounts to track the money you make, journal entries are the way to reclassify money in that original income account to the new ones.

TIP

Although journal entries are the only solution for some tasks in QuickBooks, it’s best to use QuickBooks transactions instead whenever possible. By using transactions, your QuickBooks reports will contain all the info you expect, and you’ll have the financial details you need if the IRS starts asking questions.

The steps for creating a journal entry are deceptively easy; it’s assigning money to accounts in the correct way that’s maddeningly difficult for weekend accountants. And unfortunately, QuickBooks doesn’t have any magic looking glass that makes these assignments crystal clear. This chapter gets you started by showing you how to create journal entries and providing examples of journal entries you’re likely to need. However, you’ll want to talk to your bookkeeper or accountant about the journal entries you need and the accounts to use in them.

NOTE

In the accounting world, you’ll hear the term “journal entry” and see it abbreviated JE. However, QuickBooks uses the term “general journal entry” and the corresponding abbreviation GJE. Don’t worry: Both terms and abbreviations refer to the same account register changes.

Balancing Debit and Credit Amounts

In double-entry accounting, both sides of any transaction have to balance, as the transaction in Figure 16-1 shows. When you move money between accounts, you increase the balance in one account and decrease the balance in the other—just as shaking some money out of your piggy bank decreases your savings balance and increases the money in your pocket. These changes in value are called debits and credits. (Whether the debit and credit increase or decrease the account balance depends on the type of account, as Table 16-1 shows.) If you commit anything about accounting to memory, it should be the definitions of debit and credit, because they’re the key to successful journal entries, accurate financial reports, and understanding what your accountant is talking about.

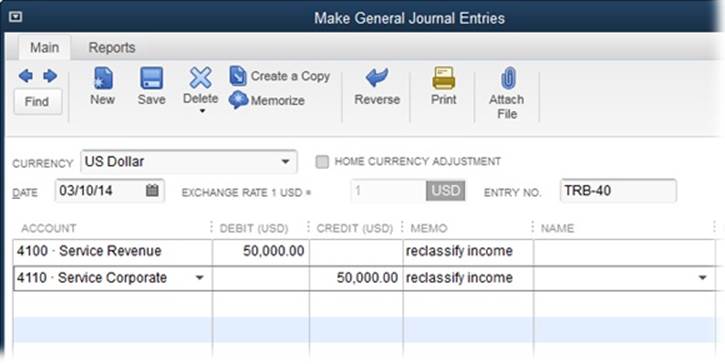

Figure 16-1. For each transaction, the total in the Debit column has to equal the total in the Credit column. To transfer money from one income account to another, you debit one account and credit the other.

Table 16-1 shows what debits and credits do for different types of accounts and can take some of the pain out of creating journal entries. For example, buying a machine is a debit to the equipment asset account because it increases the value of the equipment (assets) you own. A loan payment is a debit to your loan account because it decreases your loan balance (a liability). And (here’s a real mind-bender) a credit card charge is a credit to your credit card liability account because purchases on credit increase the amount you owe.

Table 16-1. How debits and credits change the values in accounts

|

ACCOUNT TYPE |

DEBIT |

CREDIT |

|

Asset |

Increases balance |

Decreases balance |

|

Liability |

Decreases balance |

Increases balance |

|

Equity |

Decreases balance |

Increases balance |

|

Income |

Decreases balance |

Increases balance |

|

Expense |

Increases balance |

Decreases balance |

NOTE

One reason that debits and credits are confusing is that the words have the exact opposite meanings when your bank uses them. In your personal banking, a debit to your bank account decreases its balance and a credit to that account increases its balance.

As you’ll see in examples in this chapter, you can have more than one debit or credit entry in one journal entry. For example, when you depreciate equipment, you can include a debit for the overall depreciation expense and a separate credit for the depreciation on each piece of equipment.

Some Reasons to Use Journal Entries

Here are a few of the more common reasons that businesses use journal entries:

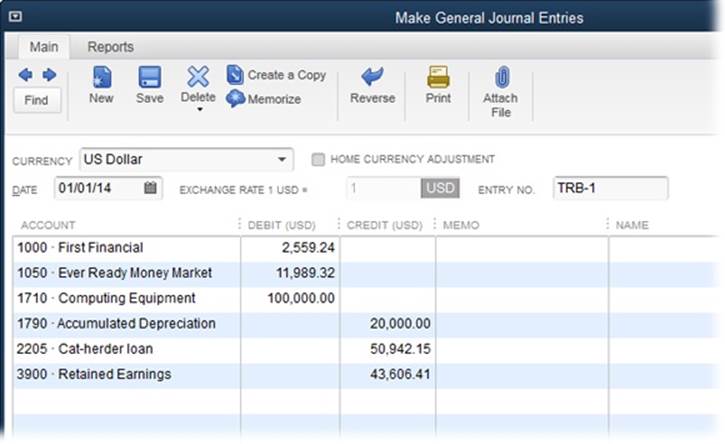

§ Setting up opening balances in accounts. You can fill in the opening balance for most of your balance sheet accounts with a single journal entry based on your trial balance from your previous accounting system. The box on Creating Opening Balances with Journal Entries explains how.

§ Reassigning accounts. As you work with QuickBooks, you might find that the accounts you originally created don’t track your business the way you want. For example, suppose you started with one income account for everything you sell—services and products alike. But now you want two income accounts: one for income from services and another for income from product sales. To move income from your original account to the correct new account, you debit the income from the original account and credit it to the new account, as described on Creating Journal Entries.

§ Correcting account assignments. If you assigned an expense to the wrong account, you or your accountant can create a journal entry to reassign the expense to the correct account. If you’ve developed a reputation for misassigning income and expenses, your accountant might ask you to assign any transactions you’re unsure about to an uncategorized income or expense account. That way, when she gets your company file at the end of the year, she can create journal entries to assign those transactions correctly. You can verify that the assignments and account balances are correct by running a Trial Balance report (Viewing Your Trial Balance).

§ Reassigning jobs. If a customer hires you for several jobs, that customer might ask you to apply a payment, credit, or expense from one job to another. For example, if expenses come after one job is complete, your customer might want to apply them to the job still in progress. QuickBooks doesn’t have a feature specifically for transferring money between jobs, but a journal entry does the trick, as Reclassifications and Corrections explains.

§ Reassigning classes. If you use QuickBooks’ class feature, journal entries can transfer income or expenses from one class to another. For example, nonprofits often use classes to assign income to programs. If you need to reassign money to a different program, create a journal entry that has debit and credit entries for the same income account but changes the class (see Creating Journal Entries).

§ Depreciating assets. Each year that you own a depreciable asset, you decrease its value in the appropriate asset account in your chart of accounts. Because no real cash changes hands, you use a journal entry to handle depreciation. As you’ll learn on Recording Depreciation with Journal Entries, a journal entry for depreciation debits the depreciation expense account (increasing its value) and credits the asset account (decreasing its value).

§ Recording transactions for a payroll service. If you use a third-party payroll service like Paychex or ADP, the payroll company sends you reports. You can then use journal entries to get the numbers from those reports into your company file where you need them. For example, you can reclassify some of your owners’ draw as salary and make other payroll-related transformations, as Reclassifying Shareholder’s Distribution to Salary explains in detail.

§ Recording year-end transactions. The end of the year is a popular time for journal entries, whether your accountant is fixing your more creative transactions or you’re creating journal entries for noncash transactions before you prepare your taxes. For example, if you run a small business out of your home, you might want to show a portion of your utility bills as expenses for your home office. When you create a journal entry for this transaction, you debit the office utilities account and credit an equity account for your owner’s contributions to the company.

Creating Journal Entries

In essence, every transaction you create in QuickBooks is a journal entry. For example, when you write checks, the program balances the debits and credits behind the scenes. The Make General Journal Entries window is the answer when you want to explicitly create journal entries in QuickBooks. Here are the basic steps:

1. Open the Make General Journal Entries window by choosing Company→Make General Journal Entries.

Or, if the Chart of Accounts window is open, right-click anywhere in the window and then choose Make General Journal Entries on the shortcut menu, or click Activities→Make General Journal Entries.

2. In the Make General Journal Entries window, choose the date you want associated with this journal entry.

If you’re creating a journal entry to reassign income or an expense to the correct account, use today’s date. However, when you or your accountant make end-of-year journal entries—to add the current year’s depreciation, say—it’s common to use the last day of the fiscal year instead.

NOTE

If you turn on QuickBooks’ multiple currency preference (Multiple Currencies), the Make General Journal Entries window includes boxes for the currency and the exchange rate. If you select an account that uses a foreign currency in a journal-entry line, QuickBooks fills in the exchange rate and asks you to confirm that the rate is correct. If it isn’t, open the Currency List (choose Lists→Currency List) and update the exchange rate for that currency.

3. Although QuickBooks automatically assigns numbers to journal entries, you can specify a different number by typing it in the Entry No. box.

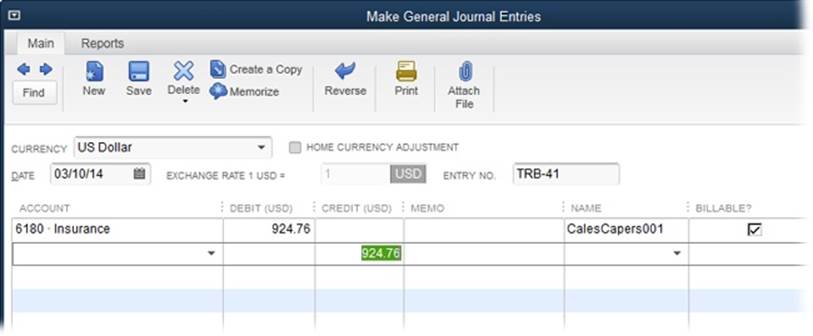

Entry numbers can contain letters, numbers, and punctuation. When you type an entry number value that includes a number, QuickBooks fills in the Entry No. box for your next journal entry by incrementing the one you typed. For example, suppose your accountant adds several journal entries at the end of the year and uses the numbers ACCT-1, ACCT-2, ACCT-3, and so on. When you begin using the file again, you can type a new number to restart your sequence, such as TRB-40 or 40TRB. When you create your next journal entry, QuickBooks automatically fills in the Entry No. box with TRB-41 or 41TRB, respectively.

TIP

If you don’t want QuickBooks to number journal entries automatically, you can turn off this feature in the Accounting preferences (Accounting).

4. In the Account cell, choose the account that you want to debit or credit.

Every line of every journal entry has to have an account assigned. When you click the Account cell in the next line, QuickBooks automatically enters the offsetting balance, as shown in Figure 16-2.

5. If you want to debit the account you just selected, on the same line in the window’s table, type the amount in the Debit cell. To credit the account instead, type the amount in the Credit cell.

The first line of your journal entry can be either a debit or a credit. However, most accountants start journal entries with a debit.

6. Fill in the Memo cell with a brief description of the journal entry’s purpose.

Entering a memo is a huge help when you go back to review your journal entries. For example, if you’re reclassifying an uncategorized expense, type something like “Reclassify expense to correct account.” For depreciation, you can include the dates covered by the journal entry.

Figure 16-2. The total in the Debit column has to match the total in the Credit column. So if the first line you enter is a debit, QuickBooks helpfully enters the same amount in the second line’s Credit column, as shown here. If your first line is a credit, QuickBooks puts the same amount in the second line’s Debit column.

NOTE

In QuickBooks Premier and Enterprise editions, the “Autofill memo in general journal entry” preference tells the program to fill each subsequent Memo cell with the text from the first one. To adjust this setting, choose Edit→Preferences→Accounting, and then click the My Preferences tab.

7. If you’re debiting or crediting an AR or AP account, choose an option in the Name cell, as explained in the box on Creating Opening Balances with Journal Entries.

You also fill in this cell if you’re creating a journal entry for billable expenses and want to assign the expenses to a customer or job. When you choose a name in this cell, QuickBooks automatically puts a checkmark in the “Billable?” cell, as shown in Figure 16-2, which reassigns some of your existing expenses to be billable to the customer or job. If you don’t want to make the value billable to the customer (for example, to assign expenses to a customer’s job to reflect its true profitability), then click the checkmark to turn it off.

8. If you use classes, choose a class for each line to keep your class reports accurate.

If you’re creating a journal entry to reassign income or expenses to a different class, select the same account on each line but different classes.

9. Repeat steps 4–8 to fill in the second line of the journal entry.

If the offsetting value that QuickBooks adds to the second line is what you want, all you have to do is choose the account for that line, fill in the other cells (if necessary), and then click Save & Close.

If the second line doesn’t balance the Debit and Credit columns, continue adding additional lines until you’ve added debit and credit amounts that balance.

10.When the debit and credit columns’ totals are the same, click Save & Close to save the journal entry and close the Make General Journal Entries window.

If you want to create another journal entry, click Save & New instead.

TIP

You can use QuickBooks’ Search and Find features to track down a journal entry. To use Search, choose Edit→Search (or press F3). In the Search window, click Transactions, and then click Journals. Finally, in the Search box at the top of the window, type keywords to search for.

To use Find, choose Edit→Find (or press Ctrl+F) to open the Find window. Click the Simple tab. In the Transaction Type drop-down list, choose Journal. Then fill in other fields that identify the journal entry you’re looking for, such as the name, date, entry number, or amount. Finally, click Find to display journal entries that match your criteria.

WORKAROUND WORKSHOP: CREATING OPENING BALANCES WITH JOURNAL ENTRIES

QuickBooks has rules about Accounts Payable (AP) and Accounts Receivable (AR) accounts in journal entries. Each journal entry can have only one AP or AR account, and that account can appear on only one line of the journal entry. And if you add an AP account, you also need to choose a vendor in the Name cell. (For AR accounts, you have to choose a customer’s name in the Name cell.)

These rules are a problem only when you want to use journal entries to set the opening balances for customers or vendors. The hardship, therefore, is minute, because the preferred approach for building opening balances for vendors and customers is to enter bills and customer invoices. These transactions provide the details you need to resolve disputes, determine account status, and track income and expenses.

You can get around QuickBooks’ AP and AR limitations by setting up the opening balances in all your accounts with a journal entry based on your trial balance (Creating an Account) from your previous accounting system. Simply create the journal entry without the amounts for Accounts Payable and Accounts Receivable, as shown in Figure 16-3.

Figure 16-3. When you use journal entries to create opening balances, you have to adjust the values in your equity account (like retained earnings) to reflect the omission of AP and AR. Then you can create your open customer invoices and unpaid vendor bills to build the values for Accounts Receivable and Accounts Payable. When your AP and AR account balances match the values on the trial balance, the equity account will also match its trial balance value.

Checking Journal Entries

If you stare off into space and start mumbling, “Debit entries increase asset accounts” every time you create a journal entry, it’s wise to check that the journal entry did what you wanted. Those savvy in the ways of accounting can visualize debits and offsetting credits in their heads, but for novices, thinking about the changes you expect in your Profit & Loss report or balance sheet is easier.

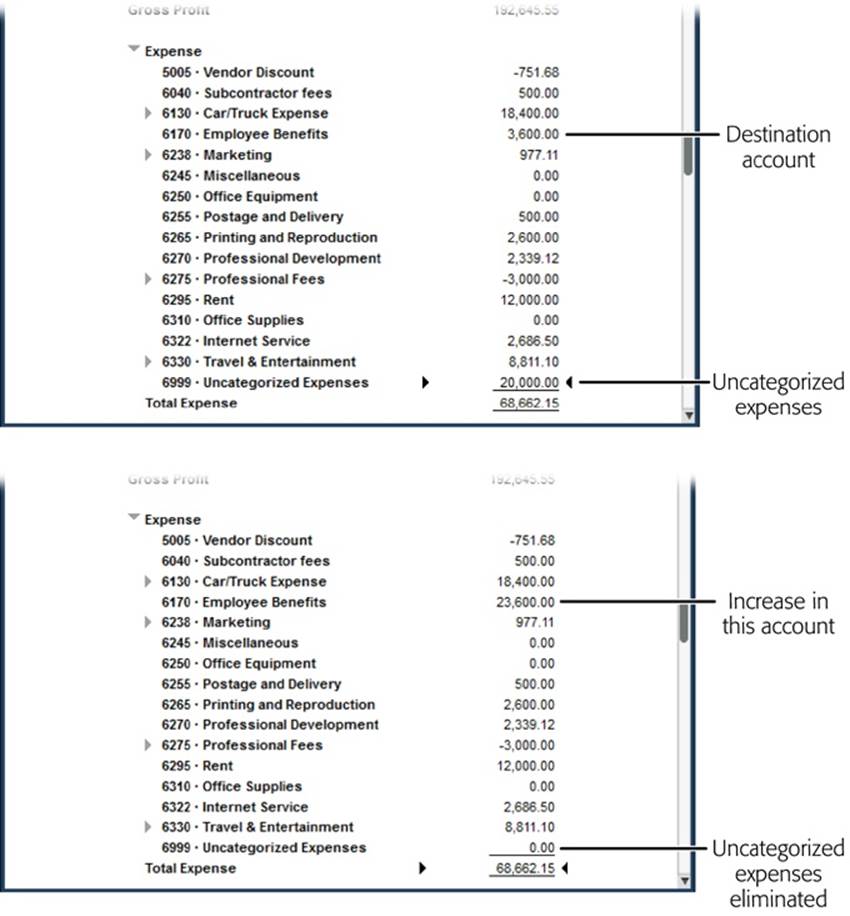

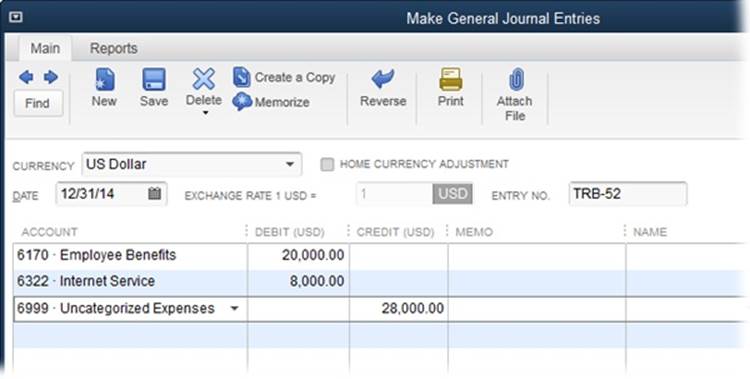

For example, if you plan to create a journal entry to reassign expenses in the Uncategorized Expenses account to their proper expense-account homes, you’d expect to see the value in the Uncategorized Expenses account drop to zero and the values in the correct expense accounts increase.Figure 16-4 shows how to use a Profit & Loss report (Generating Financial Reports) to check your journal entries.

Figure 16-4. Top: Before you create a journal entry, run a Profit & Loss report and look at the accounts that you expect to change. Here, the Uncategorized Expenses account has $20,000 in it and the Employee Benefits account, which is the destination for your uncategorized expenses, has $3,600. Bottom: After the journal entry reassigns the expenses, refresh the report (page 664) in its report window to see the journal entry’s effect. Here, you can see that the Uncategorized Expenses account’s balance decreased, as you’d expect, and the Employee Benefits account’s balance increased.

NOTE

Some journal entries affect both Balance Sheet and Profit & Loss reports. For example, as you’ll learn on Recording Depreciation with Journal Entries, a depreciation journal entry uses an asset account (which appears only in the Balance Sheet report) and an expense account (which appears only in the Profit & Loss report). In situations like this, you have to review both reports to verify your numbers.

Reclassifications and Corrections

As you work with your QuickBooks file, you might realize that you want to use different accounts. For example, as you expand the services you provide, you might switch from one top-level income account to several specific income accounts. Expense accounts are also prone to change—like when the Home Office account splits into separate accounts for utilities, insurance, and repairs, for example. Any type of account is a candidate for restructuring, as one building grows into a stable of commercial properties, say, or you move from a single mortgage to a bevy of mortgages, notes, and loans. Whatever the situation, journal entries can help you put funds in the proper accounts.

Reclassifying Accounts

Whether you want to shift funds between accounts because you decide to categorize your finances differently or you simply made a mistake, you’re moving money between accounts of the same type. The benefit to this type of journal entry is that you have to think hard about only one side of the transaction—as long as you pick the debit or credit correctly, QuickBooks handles the other side for you.

The debits and credits you choose are the opposite for income and expense accounts. For example, Figure 16-1 shows how to reclassify income, where you debit the original income account to decrease its value and credit the new income accounts to increase their value. Figure 16-5 shows how to reclassify expenses, in which you credit the original expense account to decrease its value and debit the new expense accounts to increase their value.

TIP

Accountants sometimes create what are known as reversing journal entries, which are journal entries that move money in one direction on one date and then move the money back to where it came from on another date. Reversing journal entries are common at the end of the year, when you need your books configured one way to prepare your taxes and another way for your day-to-day bookkeeping. To create a reversing journal entry that uses the same accounts—but with opposite assignments for debits and credits—first, in the Make General Journal Entries window, display the journal entry you want to reverse. Then, at the top of the window, click the Reverse icon.

Reassigning Jobs

If you need to transfer money between different jobs for the same customer, journal entries are the answer. For example, a customer might ask you to apply a credit from one job to another because the job with the credit is already complete.

Figure 16-5. The debits and credits for expense accounts are the opposite of those for income accounts: You credit the original expense account to decrease its value and debit new expense accounts to increase their value.

When you move money between jobs, you’re transferring that money in and out of Accounts Receivable. Because QuickBooks allows only one AR account per journal entry, you need two journal entries to transfer the credit completely. (Figure 10-34 shows what these journal entries look like.) You also need a special account to hold the credit transfers; an Other Expense account called something like “Clearing Account” will do. After you have the holding account in place, here’s how the two journal entries work:

§ Transfer the credit from the first job to the holding account. In the first journal entry, debit Accounts Receivable for the amount of the credit. (Choose the customer and job in the Name cell.) This half of the journal entry removes the credit from the job’s balance. In the second line of the journal entry, choose the holding account. The amount is already in the Credit cell, which is where you want it for moving the amount into the holding account.

§ Transfer the money from the holding account to the second job. In this journal entry, debit the holding account for the money you’re moving. Then the AR account receives the amount in its Credit cell. In the Name cell in the AR account line, choose the customer and the second job. This journal entry transfers the money from the holding account to the second job’s balance.

Recording Depreciation with Journal Entries

When you own an asset, such as the Deluxe Cat-o-matic Cat Herder, the machine loses value as it ages and clogs with fur balls. Depreciation is an accounting concept, intimately tied to IRS rules, that reduces the value of the machine and lets your financial reports show a more accurate picture of how the money you spend on assets links to the income your company earns. (See the box on How Depreciation Works for an example of how depreciation works.)

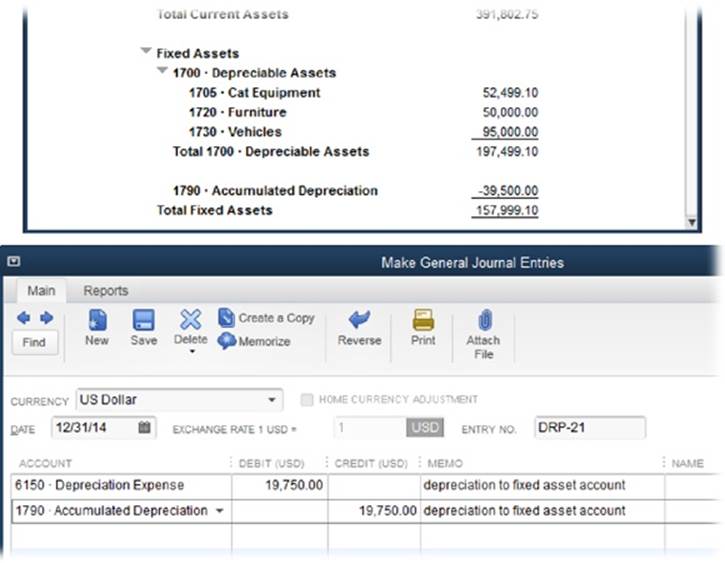

Typically, you’ll calculate depreciation in a spreadsheet so you can also see the asset’s current depreciated value and how much more it will depreciate. But depreciation doesn’t deal with hard cash, which is why you need to create a journal entry to enter it. Unlike some other journal entries, which can use a wide range of accounts, depreciation journal entries are easy to create because the accounts you can choose are limited. Here’s how it works:

§ The debit account is an expense account, usually called Depreciation Expense. (If you don’t have a Depreciation Expense account, see Creating Accounts and Subaccounts to learn how to create one.)

§ The credit account is a fixed asset account called something like “Less Accumulated Depreciation.” Figure 16-6 (top) shows how to set up your fixed asset accounts for things like machinery, vehicles, and furniture. You create a parent fixed asset account called Depreciable Assets, and then create separate fixed asset subaccounts within the Depreciable Assets account so you can see the total value of all your fixed assets on your balance sheet. The Accumulated Depreciation account (which you also create) appears after the depreciable asset accounts at the same level as the parent Depreciable Assets account, so you can see how much depreciation you’re deducting.

Figure 16-6. Top: A parent fixed asset account called Depreciable Assets acts as a container for all your fixed assets, so you can see the total fixed asset value on your balance sheet. The Accumulated Depreciation account follows the parent Depreciable Assets account, so you can see the depreciation you’ve deducted. Bottom: If you have several assets to depreciate, the commonly accepted approach is to create a spreadsheet showing the depreciation for each individual asset. In QuickBooks, you simply record a single Depreciation Expense debit for the total of all the depreciation credits, as shown here.

TIP

If you depreciate the same amount each year, memorize the first depreciation transaction you create (Memorizing Transactions). The following year, when it’s time to enter depreciation, press Ctrl+T to open the Memorized Transaction List window. Select the depreciation transaction, and then click Enter Transaction.

Another way to copy a journal entry is to open the Make General Journal Entries window and then click Previous until you see the journal entry you want. Then right-click the window and choose Duplicate Journal Entry from the shortcut menu. Make the changes you want, and then click Save & Close.

For a depreciation journal entry, you want to reduce the value of the fixed asset account and add value to the Depreciation Expense account. If you remember that debit entries increase the value of expense accounts, you can figure out that the debit goes with the expense account and the credit goes to the fixed asset account. Figure 16-6 shows how depreciation debits and credits work.

UP TO SPEED: HOW DEPRECIATION WORKS

When your company depreciates assets, you add dollars here, subtract dollars there—and none of the dollars are real. It sounds like funny money, but depreciation is an accounting concept that presents a more realistic picture of financial performance. To see how it works, here’s an example of what happens when a company depreciates a large purchase:

Suppose your company buys a Deep Thought supercomputer for $500,000. You spent $500,000, and you now own an asset worth $500,000. Your company’s balance sheet moves that money from your bank account to a fixed asset account, so your total assets remain the same.

The problem arises when you sell the computer, perhaps 10 years later when it would make a fabulous boat anchor. If you don’t depreciate the computer, the moment you sell it, its value plummets from $500,000 to your selling price—$1,000, say. The decrease in value shows up as an expense, putting a huge dent in your profits for the 10th year. Shareholders don’t like it when profits change dramatically from year to year—up or down. With depreciation, though, you can spread the cost of a big purchase over several years, which does a better job of matching expenses to the revenue generated by the asset. As a result, shareholders can see how well you use assets to generate income.

Depreciation calculations come in several flavors: straight-line, sum of the years’ digits, and double declining balance. Straight-line depreciation is the easiest and most common. To calculate annual straight-line depreciation over the life of the asset, subtract the salvage value (how much the asset will be worth when you sell it) from the purchase price, and then divide by the number of years of useful life, like so:

§ Purchase price: $500,000

§ Expected salvage value after 10 years: $1,000

§ Useful life: the 10 years you expect to run the computer

§ Annual depreciation: $499,000 divided by 10, which equals $49,900

Every year, you use the computer to make money for your business, and you show $49,900 as an equipment expense associated with that income. On your books, the value of the Deep Thought computer drops by another $49,900 each year, until the balance reaches the $1,000 salvage value at the end of the 10th year. This decrease in value each year keeps your balance sheet (The Balance Sheet) more accurate and avoids the sudden drop in asset value in year 10.

The other methods—which are more complex—depreciate assets faster in the first few years (called accelerated depreciation), making for big tax write-offs in a hurry. Recording Depreciation with Journal Entries explains how to record journal entries for depreciation, but your best bet is to ask your accountant how to post depreciation in your QuickBooks accounts.

Recording Owners’ Contributions

Most attorneys suggest that you contribute some cash to get your company off the ground. However, you might make noncash contributions to the company, like your home computer, printer, and other office equipment. Then, as you run your business from your home, you may want to allocate a portion of your mortgage interest, utility bills, homeowners’ insurance premiums, home repairs, and other house-related expenses to your company. In both these situations, journal entries are the way to get money into the accounts in your chart of accounts.

TIP

If you write a personal check to jump-start your company’s checking account balance, simply record a deposit to your business checking account and assign that deposit to your owners’ equity account.

Recording Initial Noncash Contributions

When you contribute equipment to your company, you’ve already paid for the equipment, so you want its value to show up in your company file. You can’t use the Write Checks window to make that transfer, but a journal entry can record that contribution:

§ Credit the owners’ equity account (or common stock account, if your company is a corporation) with the value of the equipment you’re contributing to the company.

§ Debit the equipment asset account so its balance shows the value of the equipment that now belongs to the company.

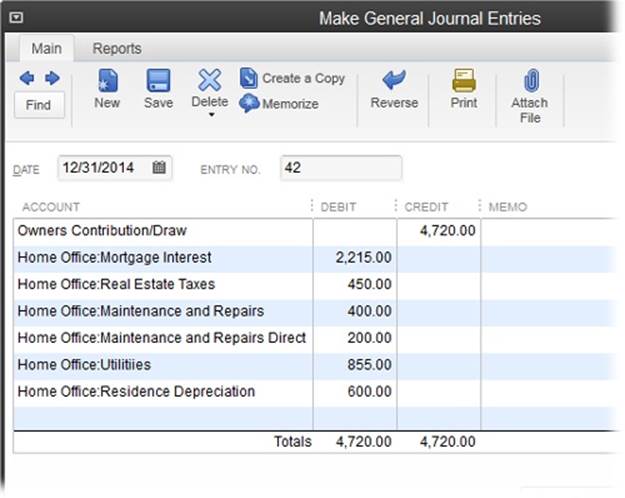

Recording Home-Office Expenses

If you use a home office for your work, the money you spent on home-office expenses is already out the door, but those expenditures are equivalent to personal funds you contribute to your business. If your company is a corporation, you credit your equity account with the amount of these home-office expenses. Here’s how you show this contribution in QuickBooks:

§ Credit the total home-office expenses to an equity account for your shareholders’ distribution or owner’s contributions to the company.

§ Debit the expense accounts for each type of home-office expense, as shown in Figure 16-7.

TIP

Another way to handle a home office is to charge your company rent for your office space. That way you, as the homeowner, have rental property, so you can depreciate the portion of your home rented to your company. (However, this depreciation complicates things down the road when you sell your home.) If your company is a corporation, it gets to take a tax deduction for rent on its corporate tax return.

Figure 16-7. After you credit the owner’s contribution account and debit the home-office expense accounts, your home-office expenses show up in the Profit & Loss report (page 453) and your owner’s contribution appears on the Balance Sheet (page 459).

If your business is a sole proprietorship, you handle home-office expenses differently: You write business checks to pay all your home expenses. When you do that, your Profit & Loss report shows your total home expenses as business expenses. But only a percentage of those expenses are business related, so you need a way to subtract the expenses that correspond to your personal use of your home. The solution? At the end of the year, create a journal entry to reallocate the personal percentage of home expenses to your owners’ draw equity account, so that only the business portion of your home expenses show up on the Profit & Loss report. Then you’ll have a section in your Profit & Loss report similar to Table 16-2.

Table 16-2. Business expenses for a sole proprietorship

|

ACCOUNT |

EXPENSE AMOUNT |

|

Business Use of Residence |

$17,800 (This is a summary account for the accounts starting with Mortgage Interest through Other Utilities) |

|

Mortgage Interest |

$9,000 |

|

Real Estate Taxes |

$2,250 |

|

Real Estate Insurance |

$750 |

|

Maintenance and Repairs |

$2,400 |

|

Maintenance and Repairs Direct |

$200 |

|

Other Utilities |

$3,200 |

|

Less 80.0% Personal Use |

$14,080 |

|

Residence Depreciation |

$1,000 |

|

Total Business Use of Residence |

$4,720 |

NOTE

The “Maintenance and Repairs Direct” line represents expenses directly related to the home office, so the full amount goes toward the home-office expenses. Similarly, the Residence Depreciation line is the amount of depreciation for the portion of the house used as a home office.