Understanding Context: Environment, Language, and Information Architecture (2014)

Part III. Semantic Information

Chapter 10. The Written Word

To imagine a language is to imagine a form of life.

—LUDWIG WITTGENSTEIN

The Origins of Writing

MOST OF WHAT WE DESIGN INVOLVES WRITING IN ONE WAY OR ANOTHER, and writing has properties that are different from aural communication. Writing is much newer, but it’s no less fundamental to our daily reality.

Writing as we know it emerged as an elaborate game of charades using scribbled and imprinted signs to create a mélange of evocations—some representational pictures, some phonetic, some a combination of both. Eventually writing became much more about encoding the richness of verbal language than mere pictorial representation, because the pictures were quickly co-opted into representations of the sounds of oral language, instead.[210] That is, pictograms were transformed into phonograms. After all, oral language was already a much more sophisticated and capable ability: why keep using clunky pictures strung together when so much nuance was possible by mimicking the sound of just talking?

Enter the use of phonetic writing. For example, a picture of a bull with horns might be co-opted to stand for a spoken sound that means “king.” When that innovation happens, the flood gates open: writing starts being used mainly as a way to encode verbal language.[211] Chapter 9 relates how research has shown that our nervous systems fire signals for reading aloud even when we’re reading silently. When we read the written word, we are picking up information from the marks on a surface representing the bodily sounds we make when speaking; and because we’ve been taught (usually from an early age) how to decipher these marks, we have learned how to translate the physical affordance of “seeing marks on a surface” into the mediated meaning we get from “reading.” As we become more practiced readers, we hardly notice that this sound-deciphering is going on. It feels as if we are directly perceiving the meaning on the page.

What Writing Does

In the terms of environmental elements, writing changes language from an oral variant event to a written invariant object. And that affords abilities that did not exist previously.

Oral language is trapped within an event-based, physically constrained mode of experience. Prior to writing, the only way to store and retrieve semantic information was to memorize it. In The Art of Memory (Pimlico), Frances A. Yates famously explains that orators developed elaborate mnemonic methods for retaining long speeches.

They imagined a huge house with many rooms, and then placed images or objects in the rooms that reminded the orator of the language that is to come next in the oration. “We have to think of the ancient orator as moving in imagination through his memory building whilst he is making his speech, drawing from the memorized places the images he has placed on them.”[212] This strategy of using imagined rooms—physical information about places and connections between them—makes sense, given that we know memory is built up from physical experience of structural patterns in the environment. Yet, even for these incredibly adroit memorizers, the information was only “inside their heads” and could be expressed only orally, part of a linear narrative, spoken as an event of sound vibrating the air and disappearing.

Eventually some of these orators wrote down what they had memorized, which moved the cognitive work from the body to the surfaces of the environment. Writing meant that language wasn’t just a stream of sounds that came and went; it allowed communication to be encoded into actual objects.

Even in the most advanced digital devices and software, spoken words are under event-based, linear constraints. When I use my car’s GPS, the device speaks the directions, but if I’m distracted and don’t hear them clearly, too bad—they’re gone. I have to look at the written information on the screen (as well as the graphical semantic information, such as the map and status icons) to reference and analyze where I’m going. The entire concept of referencing information or “looking it up” wouldn’t exist without writing.

Writing enabled us to freeze our ideas in time and space and then dissect and study them.[213] By separating the communicated thought from the moment, we can organize our experience in a different way. Writing brings the ability for us to be “meta” about our experience; to not just share knowledge but to make knowledge, and then make knowledge about knowledge itself. This turn brings with it the ability to organize information in completely new and innovative ways, untethered from the tyranny of linear, ephemeral speech.

The practical implications of this shift are significant. Here are some of the abilities with which writing imbues us that we did not have before:

Categories, and categories of categories

Oral language already uses categorical concepts. As philosopher and author Andy Clark told us in Chapter 9, labels give us “cheap” ways to group elements of the environment without having to actually move them physically, and to group things together that we wouldn’t be able to move to begin with. But with writing, categorization really comes into its own. Classification moves from being something we use for organizing language about elements of our environment (animals, plants, and so on) to also being a way for us to organize the objects we’ve written upon, and even the ideas written about.

Abstraction

Categorization introduces a whole new dimension of abstraction; the power it gives us to organize also results in further distancing information from its original signification. Classifying ideas produces semantic information that’s even more abstract. We can make symbols for classes of symbols, which can then be classified yet again, ad infinitum.

Proliferation

Writing means that the semantic information we create persists in the environment; it doesn’t go away unless its medium decays or we lose it or destroy it. Before long, the written artifacts really start to pile up. We eventually have a big challenge for what to do with all this written information that would have previously vanished into the air.

Storage and retrieval

Classification helps us devise ways to organize all these artifacts so that we can find them later. But the manner in which we classify information into categories is, in and of itself, a new sort of infrastructure that adds new information—new environment—to what already exists. Semantic information ushers in new activities of storing, and then retrieving (by first finding) information. These were activities humans previously performed only with physical elements of the environment. Hunting, gathering, storing, consuming—all the embodied actions we used for millions of years for survival, now being employed in the meta-dimension of the information we created for ourselves. But instead of objects being nested within features of the terrain, we create our own nested terrain made of lists and categories. The way in which we organize information in mechanisms such as databases matters with respect to how we can interact and have conversations with it, and how it can help us understand the world it represents.[214]

Logic

The ability to write down ideas and analyze them, seek out their structures and reconfigure them into new combinations is a necessary condition for formal logic. Author and historian James Gleick explains, “Logic descended from the written word, in Greece as well as India and China, where it developed independently. Logic turns the act of abstraction into a tool for determining what is true and what is false: truth can be discovered in words alone, apart from concrete experience.”[215] The ability to embody logical operations in language also helps set the stage for digital information—abstractions used as building blocks for new structural realities.

Complexity of thought

Being able to put our thoughts into the world as marks on surfaces gives us the ability to reflect on what we’ve written as reified objects. We can forget about them and come back to them, or we can add to them later. It supercharges our ability to create elaborate, vast conceptual systems. And it makes it possible for us to have thoughts that simply wouldn’t have been possible otherwise.[216]

Transmission

Rather than sending a human with a memorized oral message, writing facilitates the message to be sent as an object, like any other cargo. It can be written in someone’s “own hand” and sealed with a representation of their physical presence. That is, it affords a person the ability to be represented more intimately and directly to another, across time and space. And it allows these messages to take the form of infrastructure, stitching together cities and towns with invariant structures rather than variant events.

Writing enables us to create logically structured, transmittable, stored and retrieved semantic information. It brings a whole new dimension of communication and understanding, and gives us the capability to create persistent linguistic scaffolding for enhancing the natural and built physical environment. The ability to label, direct, and instruct through written language and semantic graphics is a huge boon to creating the context of inhabited environments; it is part of what makes civilization possible.[217]

But writing also opens a sort of Pandora’s box of environmental abstraction because it allows us to (in a sense) create scaffolds for scaffolds: environments that are mostly language referring to language—and ideas built on top of ideas—where there’s little (if any) physical information to orient us to something concrete. The less physical information available to us, the less we can rely on the most ancient and capable aptitudes of our perceptual systems. It’s this quality of writing that eventually leads to the characteristics of the digital mode of information, which we will explore in Chapter 11.

LISTS

The list is the origin of culture. It’s part of the history of art and literature. What does culture want? To make infinity comprehensible.

—UMBERTO ECO[218]

Plain, mundane lists are one of the oldest (see Figure 10-1) and most useful forms of written language ever invented—and a prime example of how we use language as environmental infrastructure. They make labels—names of things—into structures that allow us to move the world around with only a pencil and paper (or a stylus and a slab of clay). Lists were among the first written artifacts ever made, and were possibly a main driver behind the invention of writing in the first place.

Paris)Wikimedia Commons “List of possessions of a temple,” ()." width="250" height="375" />

Paris)Wikimedia Commons “List of possessions of a temple,” ()." width="250" height="375" />

Figure 10-1. A cuneiform tablet listing a temple’s possessions (shown at the Louvre, Paris)[219]

We take them for granted, but they still have an important role in everything we do. Especially in complex, high-stress situations, lists can literally save lives. In 1935, the United States Army was losing a depressing number of the new, complex Boeing B-17s—not to mention its pilots—to human error during takeoff and landing. Then, bomber crews were required to use procedural checklists: accident rates dropped to nearly zero. The requirement eventually had a major effect on Allied efforts in World War II.

Skip to 50 years later, and this ancient bit of infrastructure saved the day yet again, this time in hospitals, which were suffering from high infection rates and mortality due to infections from routine procedures. In a single initiative within Michigan alone, requiring checklists for such procedures saved “an estimated hundred and seventy-five million dollars in costs and more than fifteen hundred lives.”[220]

In both of these cases, the people who were making life-endangering errors were experts. The army pilots, doctors, and nurses all had thousands of hours of experience. Ironically, it was their experience that was the problem: the more we do something, the more we satisfice, taking shortcuts without realizing it.

For simple physical tasks, where any harm is evident immediately through feedback, negative consequences can be calibrated against by our bodies. But when complex systems are involved (whether vast, complicated bomber aircraft or organic, invisible systems such as bacteria)—systems we can’t perceive all at once and react to naturally—we need to add environmental structure to keep us on track.

The Structure of Writing

Oral language relies on the rhythms of speech for a lot of its context, and its form comes from how we express it with our bodies—our breathing, pitch, gestures, and more. Thus, writing requires even more care with how we structure sentences to ensure that we convey the full meaning of a message.

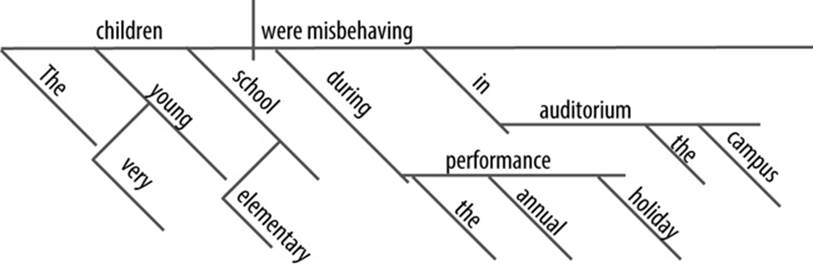

This is why many languages developed more standardized grammatical conventions. At one time, it was common practice for schools to teach grammar by using sentence diagrams, such as that shown in Figure 10-2.

Figure 10-2. A sentence about elementary school children misbehaving in a performance, broken into a standard English sentence diagram format[221]

Writing gives us the ability to put what we say onto a surface and analyze it in a way that wasn’t possible with oral speech. It makes it possible for us to have invariant objects that show these patterns, so we can point to them and agree on not just the structure, but what names we use to categorize the parts. Standardization is possible only because writing takes the tacitly nested parts of oral speech and makes them into explicitly manifested objects.

Eventually, many languages also had to develop punctuation, which brings bodily context to writing, indicating where we should pause, breathe, modulate tone up or down to indicate a question, statement, or exclamation. It adds environmental information that provides needed context that we lose without hearing it spoken.

The following joke about a panda is an often-referenced example of how punctuation changes the meaning of a statement:[222]

A panda walks into a café. He orders a sandwich, eats it, and then draws a gun and proceeds to fire it at the other patrons.

“Why?” asks the confused, surviving waiter amidst the carnage, as the panda makes toward the exit. The panda produces a badly punctuated wildlife manual and tosses it over his shoulder.

“Well, I’m a panda,” he says, at the door. “Look it up.”

The waiter turns to the relevant entry in the manual and, sure enough, finds an explanation. “Panda. Large black-and-white bear-like mammal, native to China. Eats, shoots and leaves.”

Like the quip in Chapter 9 by Groucho Marx about the elephant in pajamas, this works pretty well as joke, but it’s also a surreal and silly contrivance that doesn’t quite mirror real life. Pandas don’t talk, for one thing. And even though they have thumbs, they would have trouble getting guns into cafés.

We know the phrase “eats, shoots and leaves” is silly because we’re reading it in the context of the joke. But remove that context and put the written phrase under the pressure of literal interpretation, and it’s not unreasonable for a reader to assume it describes someone eating something, shooting something (a gun? A basketball? Or slamming back a dram of whiskey?), and then departing the premises. The more decontextualized an expression, the more important grammar becomes, meaning that a single comma—something that could be mistaken for a bit of lint—changes the nature of the world that phrase describes. This is true for human readers, but it’s especially true for language-parsing computers, which rely heavily on standard structural patterns for comprehending text.

Turning language into the infrastructure we live in, whether laws or digital systems, puts a great deal of pressure on contextual meaning. Writing is a sort of proto-technology beneath all information technology. It’s with writing that humans invented a way to encode speech for consumption outside its initial utterance. Now that we’re encoding so much of the rest of the world we live in, we find that what’s true for the context of language is also true for these other encoded “meanings”—everything from the labels on an entry form to the implied privacy of a social media conversation.

Language is not “extra”—it is central and vital. I’ve seen large corporations nearly crippled operationally because the categories used for incoming customer calls were poorly designed, and entire product categories fail because of fanciful labeling. When we sweat over content inventories and taxonomies, or we devise iconography standards and style guides, we are actually working with the beams, girders, ducts, and panels that create invariant structure for organizations, markets, and user experiences.

Rules and Systems

The structures we create with language are not only static frameworks and foundations, but conditional systems of logic and cause-and-effect that guide our actions, individually and collectively. We use them to construct cultural machinery made of rule-systems. Whether it’s the “Terms and Conditions” listed on an e-commerce website, or the way a social network platform gives us the option to “like” something but provides no equivalent function for “hating” it, rules form essential functional elements of semantic environments.

When I was a kid, I played various sorts of stickball with neighborhood friends. Each time we played, we would need to have a discussion to decide on the rules. We’d either use the rules we’d agreed upon already, or we would adjust them. We’d go over them for new players and take suggestions on improving the structures of the game. We’d inhabit that rule system together for a while, play some innings, and then break off to do something else. We didn’t have to write any of it down, because the group kept a collective recollection of the system well enough, and it kept adjusting and iterating anyway, adding to the fun.

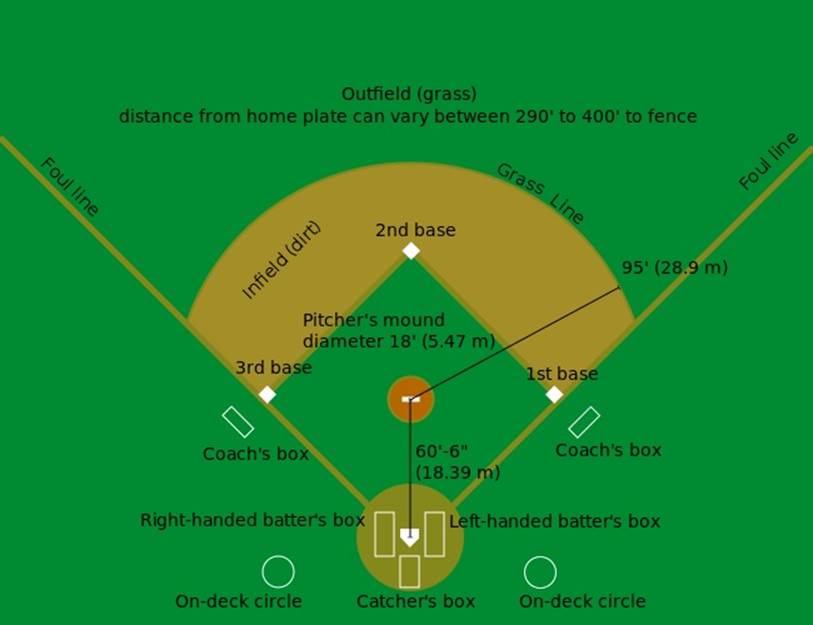

But, what if we wanted to expand the game to other neighborhoods and have some kind of official tournament? That’s how baseball emerged as a professional sport, with officially defined rules, such as those illustrated in Figure 10-3, which facilitated the game’s scaling far beyond a group of kids playing stickball.

Writing allows us to officially record rules and share them as copies far and wide. It’s the only way we can now have what we call “organized sports” at all.

Ever-expanding scale is something writing can accommodate nicely. As trade expanded thousands of years ago, it required writing to record inventories, prices, and negotiated transactions. Cities, commerce, expanding empires—all these reached a tipping point at which the “fittest” groups developed ways of keeping records, not only tallies but the agreements around the tallies as well as lots of other contextual information such as timelines and important stakeholders. Writing isn’t just a by-product of wide-scale commerce; it’s a necessary condition for having that level of commerce to begin with.[223]

Through writing, agreements can be taken out of immediate oral expression and fragile memory and made into actual, physical objects that not only contain but embody the agreements in documents. Furthermore, because documents can be copied, writing provides an infrastructure that can scale across great reaches of time and space, to an unlimited number of people, over generations.

Figure 10-3. A diagram describing the semantics of physical layout for a baseball field[224]

When you watch a team play a game of cricket or baseball, just imagine the invisible mechanisms out on the field that form the boundaries for where players can run, when they can hit the ball, and how they can throw it, what constitutes a “point” in a team’s score and what doesn’t. There’s almost nothing physical dictating these constraints—hardly any walls to speak of, no limb-restricting armatures, no team-switching mechanical apparatus. It’s just people co-inhabiting a shared understanding of a set of rules. We’re so used to it that it’s hard to realize what a miraculous and amazing invention this is.

Like perception, symbols, and context itself, this shared environment exists because of people’s actions. The teams, scorekeepers, umpires, and the rest are what make these games real. The rules in the rulebook stand as the definitive conceptual structure—a map defining the architecture for play. The game is an embodiment of the structures the rules describe. So, it doesn’t take advanced technology to blur the lines between physical and semantic information; organized sports have been around at least as long as Olympians, and they’re still an example of how the semantic system of the map and the embodied action of the territory overlap.

This overlapping and integrated reality of written language and physical action is why semantic information is so thoroughly, inseparably part of context. For humans, there’s effectively no environment that isn’t fundamentally semantic.

[210] Boulton, David, Interview with Terrence Deacon, childrenofthecode.org. September 5, 2003 (http://bit.ly/ZDcsJq).

[211] This way of interpreting signs is called the “rebus principle.” Even literal pictographic representations were quickly co-opted, transforming pictograms into what are called phonograms. A nice summary of these ideas is provided by the Metropolitan Museum of Art at http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/wrtg/hd_wrtg.htm.

[212] Yates, Frances A. The Art of Memory London: Pimlico, 1966:18.

[213] Gleick, James. The Information: A History, a Theory, a Flood. New York: Random House, 2011, Kindle locations: 622-3.

[214] Dourish, Paul, and Melissa Mazmanian (Department of Informatics, University of California, Irvine Irvine, CA). “Media as Material: Information Representations as Material Foundations for Organizational Practice.” Working Paper for the Third International Symposium on Process Organization Studies Corfu, Greece, June 2011. jpd@ics.uci.edu, m.mazmanian@uci.edu.

[215] Gleick, James. The Information: A History, a Theory, a Flood. New York: Random House, 2011, Kindle locations: 672-4.

[216] Barrett, Louise. Beyond the Brain: How Body and Environment Shape Animal and Human Minds. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2011:194-5.

[217] Wiener, Norbert The Human Use of Human Beings: Cybernetics and Society Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1954.

[218] Beyer, Susanne and Gorris, Lothar. “Spiegel Interview with Umberto Eco: ‘We Like Lists Because We Don’t Want to Die’,” Spiegel Online International (spiegel.de) November 11, 2009 (http://bit.ly/ZLUzc1).

[219] Wikimedia Commons “List of possessions of a temple,” (http://bit.ly/1wkj4HO).

[220] Gawande, Atul. “The Checklist,” The New Yorker, December 10, 2007.

[221] Based on an example from Wikimedia Commons: http://bit.ly/1DtzCkI.

[222] Truss, Lynne. Eats, Shoots and Leaves: The Zero Tolerance Approach to Punctuation. New York: Penguin, 2003.

[223] Gleick, James. The Information: A History, a Theory, a Flood. New York: Random House, 2011, Kindle locations: 759-60.

[224] Wikimedia Commons: http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Baseball_diamond.svg