Understanding Context: Environment, Language, and Information Architecture (2014)

Part III. Semantic Information

Language as Environment

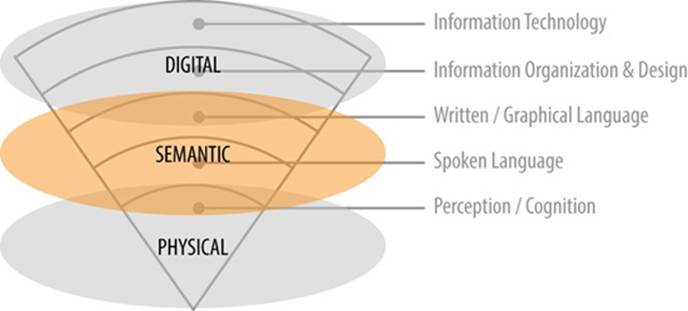

SEMANTIC INFORMATION IS WHAT WE ADD TO THE ENVIRONMENT TO MAKE IT EVEN MORE RELEVANT AND USEFUL FOR HUMANS; it’s a mirror we use to reflect upon our experience and create narratives for explaining our environments to ourselves; it’s the primary interface between humans and the complex systems that humans create. As we will see, semantic information is an inseparable and crucial part of how context is shaped in the human environment.[171]

Figure III.1. Semantic information

In Part III, we cover basic concepts about what language is and how it works. We will see how symbols give us amazing flexibility in our environment but also how they come with challenges. We’ll also see how language works as a kind of environment, functioning in ways similar to but different from physical information, and how writing enhances and changes those properties. Finally, we’ll look at how physical and semantic information intersect and how technology adds even more flexibility to the mix, with more challenges to overcome.

[171] Moving forward, I’ll be using semantic information and language interchangeably; this would not work in a linguistics classroom, but for our purposes here, it will suit fine.

Chapter 8. How Language Works

Thought is made in the mouth.

—TRISTAN TZARA

Looking at Language

TO UNDERSTAND HOW LANGUAGE FUNCTIONS AS SUCH A CRUCIAL PART of our environment, we need to look at how it manages to mean anything to begin with. That means understanding some basics about signs and symbols, the mechanisms of signification.

Language is so much a part of human life, we hardly ever think about it explicitly. Like fish in water, we just use it as a sort of natural human medium. That’s one reason language works so well. If we had to ponder the depths of meaning for every utterance, we wouldn’t get much done. In everyday usage, we frankly treat language in much the same way scholars of the sixteenth century believed language to be: that words are essentially copies of the objects they name.[172]

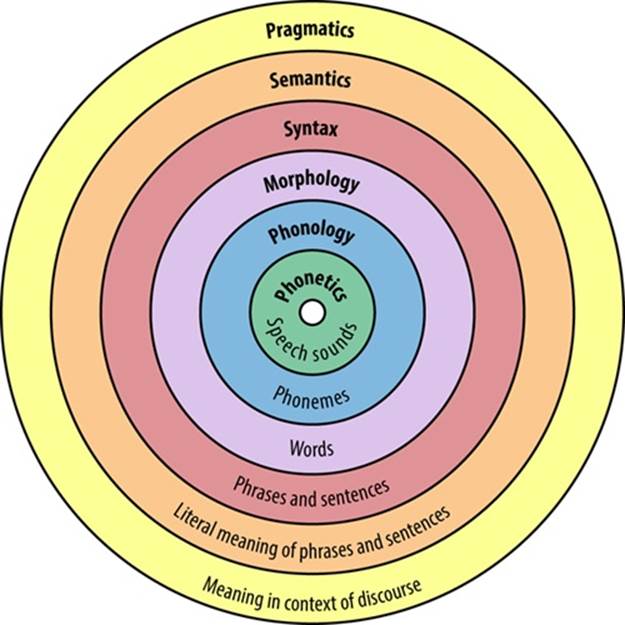

Eventually, though, the question of how language means anything became an obsession that nearly consumed the philosophical work of the twentieth century, and especially energized the field of linguistics. Over the years, linguistics experts have broken down the study of language into layers, as pictured in Figure 8-1.

Figure 8-1. Major levels of linguistic structure, from raw spoken sounds to the complexities of meanings influenced by context[173]

There is physical, ecological information involved in language, but only at the level of the center circle. (For writing, the equivalent is just the physical marks on a surface.) That is, we make phonetic sounds or physical marks, and those sounds and marks are physical structures, but they have meaning only because of the context in which they’re nested.

Language has meaning not because of its phonetic physicality but because of semantic convention. Meaning emerges from densely webbed systems of communication that have grown over millennia, built up in layers like the concentric circles of this diagram. Language is challenging to study partly because we have to use language to do so; it takes practice to pull ourselves out of the immersion within language to look at it objectively and parse its layers in this way.

Notice especially that outer layer—Pragmatics—which is the linguistic study of meaning in the context of discourse. The word “fire” literally means a number of different things, depending on where and how it is said. In the United States, there’s legal precedent constraining free public speech such that you’re not allowed to “yell fire in a crowded theater” (as the colloquial version goes), because yelling it loudly when there’s no fire can cause people to unnecessarily panic and cause injury. Ironically, many movies have people yelling “fire” in them, and it’s not a problem—same sound, same place, different context. Yelling it loudly is another factor, of course; merely whispering the word to your neighbor wouldn’t have the same effect.

Even though all of these layers are important for making understandable environments, in design work, it’s the pragmatics of linguistic meaning that often brings the biggest challenges.

Signs: Icons, Indexes, and Symbols

In the fields of linguistics and semiotics, a sign is something that can be interpreted as having a meaning other than its own form. Semantic information depends on references between a thing and what that thing means. In contrast, physical information has intrinsic meaning. Stairs mean, to my body, that I can walk up them: that relationship is directly perceived. But when I say the word “stairs,” the form of the word is not the same as the object; it only refers to the object. You can’t walk up the word “stairs.”

When we communicate with one another, we must use something other than the objects around us to make ourselves understood. Although signs exist that aren’t made by humans—for example, smoke coming from a forest is a sign that there is a fire—everything humans make to communicate meaning is a sign of one sort or another.[174]

Generally speaking, according to linguistics, there are three modes for signification—three ways in which human expression means what it means. It’s important to note that all the signifiers in the subsections that follow work, in part, because of their dependencies on other signifiers in an object or device, with icons, indices, and symbols all in the mix. Just as our environment is nested and contextual, our language use also never works as isolated parts.

Icons

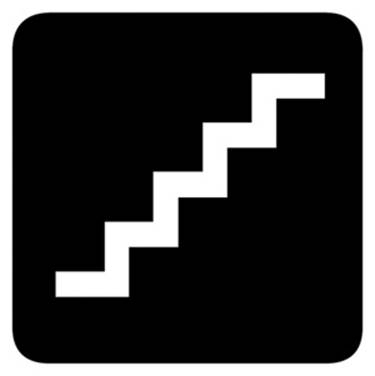

The signifier in an icon has some physical resemblance to its referent—it looks or behaves as portrayed by the signified. Many buildings have signage that depicts the shape of a stairway to mean there are stairs nearby, important for emergencies when the elevator isn’t working.

Figure 8-2. The standard icon for “stairs” from the AIGA “Symbol Signs” collection[175]

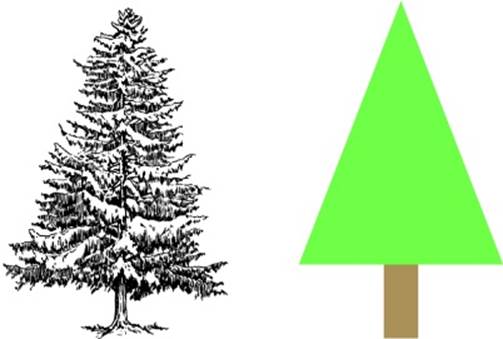

Iconic signifiers can be more or less realistically detailed. This book has a picture of a bird on the cover. That picture is an iconic reference to the type of bird—a green bee-eater. However, even a less detailed icon would work, such as a stick-figure bird, but it wouldn’t be sufficiently specific to iconically represent a particular species. Figure 8-3 demonstrates that a detailed drawing of a tree can resemble its subject down to the tiniest branch, but a simple pictograph with a green triangle and a descending brown rectangle also looks enough like a tree to be an effective iconic signifier, depending on the level of specificity required.

Figure 8-3. A line drawing of a tree represents that object iconically,6[176] but so can a simple, abstract shape

Indexes

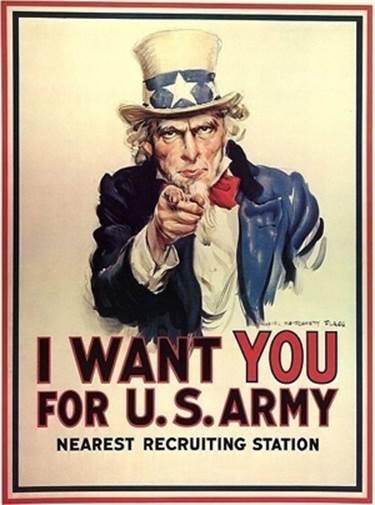

A sign that involves a direct temporal or spatial connection between signifier and signified is working as an index. An easy way to remember this one is to think of how we point at things with our index fingers. If you were to ask me where I found a pine cone, I might answer by pointing at a pine tree. My pointing at the tree is a spatial relationship between the direction of my pointing and the location of the tree. For objects small enough, we can actually pick up the object and show it; the act of showing it indicates that we are directing attention to the object. So, in answer to “which hammer did you use to repair the window?” I can grab the hammer and show it to you. In the famous World War I poster (Figure 8-4), Uncle Sam is pointing at the viewer. There are many signifiers at work in the image, but the finger pointing at the viewer indicates “You” as a potential recruit.

There can be temporal indices as well, which normally involve cause-and-effect relationships. When we see smoke, it is often an indexical signifier of a related fire. When we see a footprint in mud, we can surmise that a foot was once in that spot. And automobiles have fuel gauges, such as that illustrated in Figure 8-5, directly indicating the level of fuel in the tank—the level of fuel causes the effect of a change in the needle’s position on the gauge.

Figure 8-4. The famous World War I poster of Uncle Sam[177]

Figure 8-5. An automobile’s fuel gauge[178]

Like all signifiers, a fuel gauge means something because of its context. I can’t actually see the mechanism that is connecting this indicator with the level of fuel in my car’s tank; I have to interpret the connection. Also, the letters “F” and “E” are significant here because they are situated spatially along a continuum, with a needle that moves, in a car’s dashboard, and with a fuel-pump icon nested in the layout. Indexical and iconic signification both rely on some direct physical connection, either between the “pointer” and an object or between the physical form of a depiction and the physical form of what it portrays. In both of those modes, the signifier is specific to a particular signified referent. When I point at a pine tree, I’m not pointing at anything else. The fuel gauge is in a specific car, indicating a specific amount of fuel.

Symbols

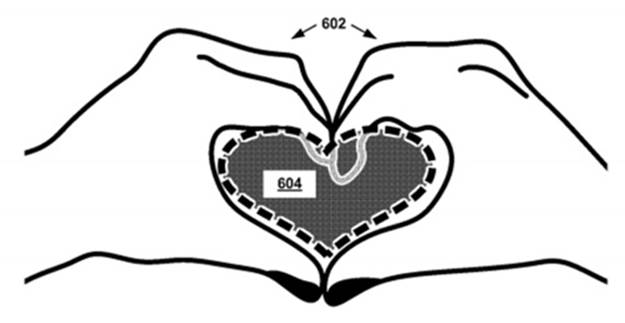

Symbols are different, in that they are signifiers that could mean anything, but have specific meaning only because of conventional usage in a given culture. We know what they mean only by experiencing their use in a system of other symbols and contexts, such as the “heart” symbol inFigure 8-6.

Figure 8-6. A gesture forming the symbol of a “heart” for “liking” something in the visual field of Google Glass (from Google’s 2013 patent)[179]

Back to our example of the stairs: I can point at a stairway in answer to the question, “Where are the stairs?” and be performing an indexical sign. Or I might see a picture that iconically represents the form of stairs, giving a clue that stairs can be found near the picture.

But if I say the word “stairs,” there is nothing in that phonetic sound that is intrinsically connected to an actual stairway; it has no uniquely bound connection other than through general agreement. Other languages don’t have to use the same words used in English; they have their own conventional combinations of different sounds, as shown in Figure 8-7.

![]()

Figure 8-7. The symbolic written signifiers for stairs, from English, Greek, Korean, and Urdu, respectively (captured from Google Translate)

The essence of a symbolic sign is that the signifier is essentially arbitrary. Any sound could have ended up as our term for stairs. Even within the same language, we have synonyms: “steps” or “stairway” or “flight,” as in, “I ran up 10 flights to get here!” That’s not to say that language is just generated randomly, like rolling dice. Etymologies often point to onomatopoeic origins, imitating the sounds of nature, such as “buzz” or “zap” or even “scream.” But most symbolic language is unmoored even from these tenuous literal connections.

The Superpowers of Symbols

Symbols are what make language so terrifically powerful: they can be variables that we can use with great flexibility to create new sorts of meaning. Here are just a few of the superpowers symbols give us:

Evocative expression

The symbolic mode gives us the capability to use words in evocative, novel ways as similes and metaphors. This can make communication much more efficient: if I say I saw a truck “jackknifed” on the freeway, it conveys a lot of meaning about the truck’s folded state that I would have otherwise needed to explain in detail. Symbols can also help us be more descriptive with language: I can describe an encounter with an attorney by saying, “That guy negotiates like a bulldog. I hate it that I got ripped off, but I swear I felt like I’d brought a banana to a knife fight.” Of course, there were no actual animals, ripping, fighting, fruit, or sharp objects involved in this situation. If all those words were confined to their more literal meanings, such a sentence would be impossible, and its replacement would be far less expressive.

Categories

Because they’re often used to point at physical objects, categories can still have an indexical flavor, but they’re freed from the tethers of specific reference. This allows us to combine concepts with other concepts. The word “mango” can mean the type of fruit rather than a specific mango I’m holding in my hand.

Categories have allowed us to organize the world around us to a scale that would’ve been impossible otherwise. The categorical label of an item makes it possible for us to find it more easily, but it can also change the way we perceive and understand that item, for good or ill.

Concepts

Symbols also allow us to work with concepts that are not categories of physical referent-objects but are new things that exist only in the realm of language and ideas. This might be the most super of our symbolic superpowers; we can create whole new environments of language-based things that we can use to solve problems, imagine new possibilities, and establish social agreements, boundaries, and expectations. In other words, symbols are the means by which we create new contexts out of nothing but language.

REIFICATION

When we reify, we take an abstraction and treat it as if it were singular and concrete. For example, we often speak of “the economy” as if it were a monolithic object we could go and touch, measure, and understand in all its dimensions. But the economy is actually made up of many millions of transactions that don’t necessarily have anything to do with one another. We do the same with concepts such as “nature,” “the media,” or “society.”

Reification is a sort of cognitive quirk that allows us to understand, communicate about, structure, and act upon the world with categories and symbols rather than having to ponder every scattered facet every time. It’s partly responsible for our ability to have language at all.

Still, like so many of our cognitive superpowers, it can also have a downside as a cognitive fallacy (called, you guessed it, the reification fallacy). We often confuse symbols or models we have created as the reality they represent. Treating the “economy” like it’s a singular thing can lead us to assume one part of it, such as the stock market, is the whole, to the detriment of all the other factors that contribute to a healthy economy, such as infrastructure, education, and healthcare. Likewise, treating “design” as a single entity with solid boundaries results in endless debates among designers online and elsewhere.

Or, take the Facebook Beacon example: here was a situation in which the idea of “friend” was reified by Facebook to mean just one narrowly defined entity. (In fact, reification is a term of art in computer science for doing pretty much this very thing.) In fact, “friend” is not unlike the idea of “the economy” or “work”—when you try pinning it down with any precision, it dissolves under your fingers, because “friend” is an abstraction we use as shorthand to describe many different sorts of relationships in many different contexts. But defining that abstraction so narrowly resulted in collapsing the contexts of many real-life relationship dimensions to a single point.

Reification is inevitable; it’s a core dynamic in how humans make meaning. So the trick is to pay attention to where it happens and ensure that it’s establishing meaning in the way we need it to.

Signification Conflation

The modes of signification help us understand how the artifacts we design can mean something to users. But in everyday life, we and our users conflate these modes all the time. We use language so naturally, with so little conscious thought, that we tend to use symbolic signs as if they were indexical or iconic.

In actual experience, we tend to reify symbols as real things because it’s quicker and easier. This is crucial to remember when we think about how we experience context: people make do in the world by satisficing. We reach for whatever tool, object, method, or mode of understanding that will get the job done with the least effort. This isn’t laziness so much as an evolutionary feature of all natural things.

This is why scholars until the sixteenth century tended to think of words as copies of what they signified; it seems obvious in the same way that it seems obvious that the sun orbits the earth. In daily life, we talk about a “sunrise”; we don’t say, “Let’s go out to the beach and watch the earth turn!” It’s only through thinking objectively about the whole system that we understand how something is actually working, rather than how we immediately perceive it. But that’s a lot of work. In the systems we design, it’s the designer’s responsibility to do that work as much as possible, so the user doesn’t have to. We want our users to be able to say “sunrise,” even if it doesn’t accurately reflect the “business rules” of how the solar system actually works. It wasn’t the users’ responsibility to comprehend the complexities of Beacon; and it wasn’t my responsibility as a user of Google Calendar to comprehend that others in my company could see some parts of my calendar but not others. It was the system’s responsibility to make its environmental invariants clear to the user.

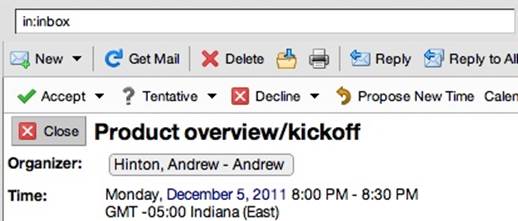

Understanding signification can help us work through everyday design issues, because digital interfaces are essentially language constructs, wherein one of the most important tasks is to disambiguate the meaning of symbols. For example, in the version of the Zimbra email interface presented in Figure 8-8, it can be hard to determine which of the red X icons one should click, if trying to do so in a hurry.

Figure 8-8. A version of the Zimbra email interface, showing an example of an email detail view

If you look at the interface closely enough and consciously ponder the layout and labels, it’s not too hard to figure out. The nested position of each X icon gives clues to its meaning, but that’s only when we pay explicit, deliberate attention. But in the heat of the workday, I found myself deleting or closing when I meant to decline an invitation, causing confusion between me and coworkers.

What was especially frustrating was that I didn’t get better at this over time, I actually got worse. Why?

My cognition’s “loop of least resistance” bends toward needing to learn an environment to the point at which I can do most or all of the actions tacitly, especially if it’s an environment I use a lot. Yet, this interface has invariant structures that look too much like one another, keeping me from being able to just mindlessly click the correct object. This environment resists learning, keeping the user in a frustrating oscillation between tacit and explicit action.

In nature, things can masquerade as other things, but it’s done for deception, allowing prey to better hide from predators, or for predators to fool their prey. Most flowers are actually flowers, not fly traps; most tree branches on the ground are wooden, not a snake. Our perception-action loop works best, and with the least confusion and explicit effort, when the environment allows us to conflate signifiers without having to solve referential puzzles.

Language Is Contextual

The contextual nature of language is something that makes semantic information fundamentally different from physical information. Language works entirely because of the context of what is said in relation to everything around it. We understand what a word means because we understand its relationship to its sentence, or the surface on which it is inscribed, or the character of the person talking. And, just as with our early diagrams of contextual relationships in Chapter 1, everything “around” a word also depends on context for its own meaning. We define words with other words or pictures of the things they name.

Shouting “fire” in a crowded theater is not the same as shouting “fire” during a military engagement. The phrase “Meet me on the bridge,” spoken by Star Trek’s Captain Kirk has a particular meaning involving space adventures and ship commands; but if spoken by Jimmy Stewart’s character in the movie It’s a Wonderful Life, “meet me on the bridge” would involve dark emotions and whimsical angels earning their wings.

Language isn’t just about words or pictures. It consumes much of what it touches, including many of the objects and surfaces in our environment. Take, for example, a simple object like the name tag in Figure 8-9.

If you see my name on a sticker affixed to my shirt, you can surmise that name is labeling me, not because of any intrinsic connection between the name and myself but through other means. There seems to be a direct indexical relationship between the written name “Andrew” and myself, because the name is “on me.” It’s one of the most straightforward ways we use language in everyday life. Yet, even that seemingly direct connection is constructed of many other elements in our surroundings:

Figure 8-9. Hello, my name is Andrew

§ The sticker is a common object for displaying one’s name at particular kinds of social functions at which strangers tend to meet and are expected to call one another by name.

§ The sticker’s layout fits a convention in which “Hello my name is” is pre-printed on the object, and participants write in their names (or the host runs the stickers through a printer, if neatness and RSVPs are high priorities).

§ If the “name” part of the sticker said “cantaloupe” and not “Andrew,” it would be ironic, because cultural convention dictates that name tags show people-names, and most people-names aren’t lowercase categories of melon.

§ At some gatherings, the cultural norm is that only newcomers wear temporary sticker name tags, which adds more context to the meaning of the object. Even these cultural norms are largely established through language use and then embodied in active ritual.

Here’s the bottom line: a name written on a person’s surface does not always mean that is the person’s name. Wearing a T-shirt that says only “Bob Dylan” on it would more likely be a minimalist concert souvenir. The words-on-person construct needs a lot more context in order to even mean something as simple as “this is my name.”

Yet, every time I see someone with a name tag, I don’t have to calculate all of this explicitly. It’s a learned feature of my environment. The name-tag object is an invariant cultural convention, learned in a system of other signifiers, just like language itself.

The Facebook “Like” is an example of a decontextualized gesture that lacks the clues I mentioned for the name tag. It’s a blunt instrument that can mean almost anything depending on what is being liked, by whom, at what time, and with what commentary. Yet, complicating it with more choices would certainly constrain user expression more than help it. In that sense, the “Like” works the way any language does.

As we will see in other examples, much of the human-made environment makes sense only because of the language that stitches its meanings together. Our physical-information environment is contextually transformed by the way we communicate about it.

[172] Chandler, Daniel. Semiotics: The Basics. New York: Taylor & Francis, 2007:71.

[173] Wikimedia Commons: http://bit.ly/1xay75J

[174] For clarity’s sake, we are skipping a lot of background here about the different schools of thought behind signification, particularly the difference between Saussure’s dyadic approach and Pierce’s triadic approach, and plenty of other important details. Beyond our scope here, these are still valuable details that I recommend curious readers investigate, because they help us think more rigorously how we design for meaning.

[175] http://www.aiga.org/symbol-signs/

[176] Wikimedia Commons: http://bit.ly/1yufIn2

[177] Wikimedia Commons: http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Unclesamwantyou.jpg

[178] Photo by author.

[179] https://www.google.com/patents/US8558759