Platform Ecosystems: Aligning Architecture, Governance, and Strategy (2014)

Part I. The Rise of Platforms

Chapter 4. The Value Proposition of Platforms

Abstract

The three groups of participants in a platform ecosystem, platform owners, app developers, and end-users, have unique needs and motivations for participating in it. Therefore, a platform must uniquely appeal to each group in how it aligns with their interests relative to a product or service. To be sustainable, a platform-based business model must also satisfy their needs better than alternative business models. This chapter focuses on the distinctive value proposition that software platforms offer to platform owners, app developers, and end-users.

Keywords

value proposition; stakeholders; platform owners; app developers; end users; business ecosystems

I conceive that the great part of the miseries of mankind are brought upon them by false estimates they have made of the value of things.

Benjamin Franklin

In This Chapter

• The value proposition of software platforms for:

• Platform owners

• Complementors (app developers)

• End-users

The three groups of participants in a platform ecosystem—platform owners, app developers, and end-users—have unique needs and motivations for participating in it. Therefore, a platform must uniquely appeal to each group in how it aligns with their interests relative to a product or service. To be sustainable, a platform-based business model must also satisfy their needs better than alternative business models. This chapter focuses on the distinctive value proposition that software platforms offer to platform owners, app developers, and end-users.

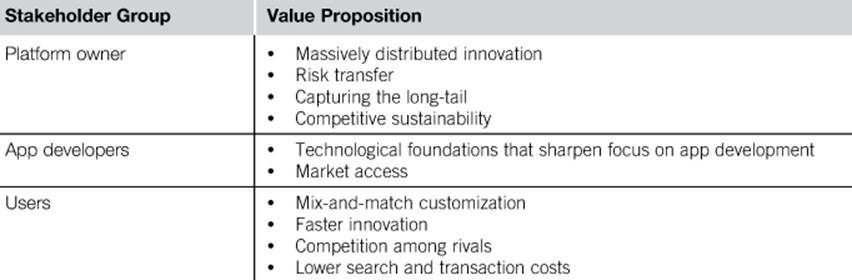

For platform owners, platforms enable massively distributed innovation on a scale that exceeds conventional product or service supply chains, transfer of the majority of costs and risks associated with innovating around the platform, allowing the platform owner to focus on doing more of what it does best and leaving the rest to its ecosystem partners, using self-interest and market incentives to align the interests of app developers with the platform’s interests, and increasing the prospects of surviving shifts, collisions, and disruptions in its markets. For app developers, platforms lower entry barriers by providing a shared foundation to use as a starting point for their own work. They also provide access to a prospective customer pool, which can find and transact with the app developers more easily through the platform than they could without it. For end-users, platforms can allow extreme levels of customization to their unique needs by enabling them to themselves mix-and-match apps that increase their personal utility of the platform. They are also the primary beneficiaries of competition among platforms and among app developers with the platform, potential usefulness-enhancing same-side network effects, and from the faster pace of innovation that can increase the usefulness of their initial investment in a platform over time. These value promotions are summarized in Table 4.1 and are discussed next.

Table 4.1

The Value Proposition of Platforms for Platform Owners, App Developers, and End-Users

4.1 Platform owners

The value proposition of a platform for the platform owner is fourfold: (1) massively distributed innovation, (2) risk transfer, (3) capturing the market’s long-tail, and (4) increased competitive sustainability.

4.1.1 Massively distributed innovation

The primary value proposition of platforms for platform owners is the potential to innovate on a scale and scope around the platform that are inconceivable in a traditional firm. Platforms allow the platform owner to infuse the power of competitive markets into traditional organizations. Instead of itself attempting to innovate in diverse markets and domains where the platform has potential applications, the platform owner can massively distribute innovation work to large numbers of app developers. Applications are where the real value in differentiating a platform from the end-users’ perspective comes. Such app developers are often closer to the pulse of their market, can bring deep and nuanced understanding of their customer segments and application domains to the table, and can collectively generate a constant stream of innovations that complement the platform. Mobilizing local insights of its complementors allows a platform to potentially penetrate diverse market domains, industries, and geographies, often far beyond what the platform owner might have been able to envision. Theoretically, all of this could be done inhouse by a single firm. But realistically, the economics of attempting it and the distraction from the firm’s core competence associated with it make it almost unfeasible.

As the old adage goes, producing good ideas requires producing more ideas. And the best way to produce more innovative ideas is to have many minds independently attack a problem space with diverse approaches. Platform-based ecosystems therefore have the potential capability to create entirely new platform capabilities through partitioning of innovation activities and their integration (Dougherty and Dunne, 2011). As long as the platform owner can successfully foster competition among application developers in the same space, it is likely that different developers will experiment using a variety of approaches, designs, and solutions to meet the needs of their own markets. This parallel approach to innovation and problem solving that rewards the survival of the fittest solution is a far cry from a single firm that typically can select only one approach for addressing a customer problem or emerging need. This increases the likelihood that some innovative solutions out of multiple competing ones will stick and help maintain the platform’s differentiation in the market. At the same time, it allows the platform owner to specialize in its core activities even more narrowly and deeply. The pursuit of innovation around the platform by many complementors can also accelerate the rate at which innovations are realized across the platform’s ecosystem. This acceleration of the innovation clock speed raises the bar for rival platforms and products.

4.1.2 Risk transfer

App developers bear most of the financial risk in pursuing their own ideas for apps for a platform. Therefore, unlike traditional product development, the costs and risks of developing new platform-specific innovations shift from the platform owner to app developers. These app developers are driven by the hunger to succeed, with the prospects of large payoffs if they do. App developers can therefore bolster the platform’s competitive advantage purely by pursuing their selfish self-interest (but only if governance is gotten right). Therefore market success and failure functions as a built-in disciplining device for app developers in platform markets. The platform owner’s fixed costs of developing and maintaining the platform also can be spread across many app developers and users.

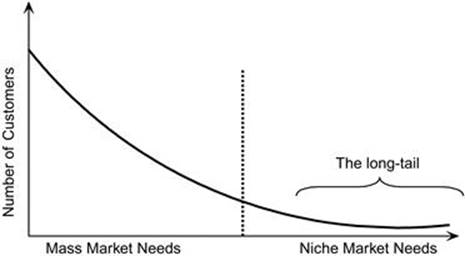

4.1.3 Capturing the long-tail

Platform markets have two pieces: a mass market that characterizes its average consumer and a niche market that demands functionality, which is so different from the typical consumer that relatively small incremental quantities of a product or service can be sold if the platform catered to that market (see Figure 4.1). Therefore, firms often must focus on the needs of the mass market in conceiving new products and services, which they can deliver with economies of scale and sell in large volumes. However, the long part of the tail—the niche markets with highly specialized and uncommon needs—are often more than one homogenous group of niche customers. There are often many small niche groups of customers with fairly unique needs that would be economically unfeasible for one firm to try to please. The many niche markets that are economically impractical for a firm to cater to can collectively add up to a substantial lost opportunity, sometimes adding up to exceed the size of the mass market. Companies like Amazon understand this, and have successfully addressed the long-tails of the markets that their real-world rivals such as Barnes and Noble cannot justify satisfying. Think of the likelihood of your local bookstore carrying a book on logistic regression that maybe two customers will buy in a year. This would take away from the space used to stock a popular bestseller that might sell a thousand copies a year.

FIGURE 4.1 Platform owners can use ecosystems to capture their market’s long-tail.

A platform strategy potentially allows the platform owner to capture such niche markets without having to attempt to create products and services for them. Instead, app developers might find the niche markets lucrative enough to pursue using the platform as a foundation. The platform owner can therefore penetrate many market niches without bearing the direct costs or risks of dabbling in them (Meyer and Selinger, 1998). By mobilizing a diverse army of complementary resources and expertise to tackle the long-tails of the platform’s market, the platform owner can remain focused in its core activities and on the mass market while bolstering the prospects that the platform will meet complex and diverse demands for specialized, customized solutions from customers in their market’s long-tail (Williamson and De Meyer, 2012). This allows mass customization taken to an extreme because it allows the platform’s end-users in microscopic segments of the long-tail to mix-and-match apps from the ecosystem to meet their unique needs.

A platform that successfully captures the long-tail of its markets using its ecosystem can create a win–win, pie-expanding payoff for everyone involved. Amazon, for example, had 300,000 outside developers and 2 million third-party sellers using its platform extensions, collectively accounting for 36% of its $18 billion revenue in 2012. Apple similarly has paid about $10 billion in royalties to its iOS developers—far exceeding what the entire U.S. book publishing industry annually pays in royalties to all of its authors combined.

4.1.4 Competitive sustainability

A platform-based strategy also has the potential to increase a platform’s competitive sustainability. Platforms can become exponentially more popular as they grow in popularity; success begets more success, at least in the short term. Rapid access to a diverse variety of complements increases the value of the platform to both existing and prospective end-users. Attracting a diversity of outsiders with deep domain expertise and intrinsic hunger to innovate around a platform can create a self-positive cycle: The more end-users can do using a platform, the more attractive it will be for them. The more users a platform has, the more attractive app developers are likely to find it. Platforms can therefore catalyze a virtuous cycle once the bedeviling problem of attracting both sides is overcome (Eisenmann et al., 2006). Once established, platforms can also be notoriously difficult to dislodge because a rival would not only have to deliver a better price–performance ratio but would also have to rally app developers around it. This ensures that once the positive cycle begins, the platform will be better able to evolve and dynamically reconfigure to shifting user bases and emerging needs. But this is just one of the many ways explored in this book that a platform can bolster its competitive sustainability. Many other design and governance tools can strengthen such network effects and create noncoercive, value-driven lock-ins for users.

4.2 App developers

The value proposition of platforms for app developers and external complementors are twofold: (1) a technological foundation that provides app developers the advantages of scale without ownership and (2) market access.

4.2.1 Technological foundations

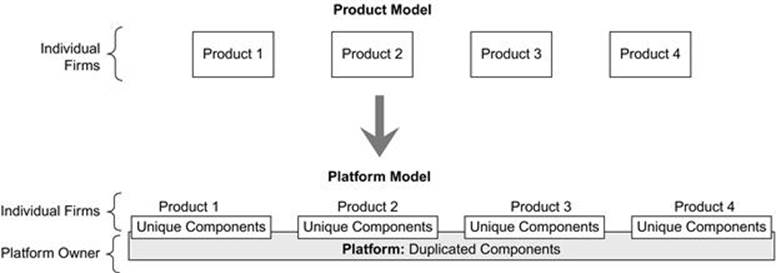

A software application has two broad functional elements: (1) those unique to the market niche of an individual app and (2) those that it shares in common with at least some other apps. The value of the app is mostly created from the unique functional elements, but the common, somewhat generic functional elements are necessary for the unique elements to function. A platform can aggregate the common elements of functionality and provide them as the foundation on which app developers can build unique elements. This is often accomplished in software platforms by services and interfaces through which apps can access the common functionality. In software platforms, the platform owner therefore contributes value by provisioning the base functionality on which app developers can build their work. For example, in video gaming and hand-held gaming systems, audio, graphic processing, and networking functionality is often provisioned by the platform (for example Valve Corporation's Steam game development platform). In contemporary smartphone platforms, network access, processing, and notification functionality is often provided by the platform. This allows thousands of developers to use that common functionality as the starting point for their own work. The scalable, investment-intensive shared assets, functionality, and services provided by the platform can be leveraged by many apps. This shift in moving from a standalone product model to a platform model is illustrated in Figure 4.2.

FIGURE 4.2 How migration to platforms increases specialization among firms.

The implications of this are twofold. First, as the duplicated elements of app functionality are collapsed into the platform, app developers can afford to specialize more exclusively on producing the unique functional elements of their apps where their expertise presumably lies and where they can create more distinctive value. The costs of the shared platform are spread across many app developers, so potentially massive scale economies can be created in the shared functionality. The primary value of platform-based development for app developers is therefore the elimination of non-value-adding duplication and reduction of development costs through large-scale sharing, all without the need to overtly coordinate with other app developers (Evans and Schmalensee, 2007;Evans et al., 2006, p. 17). Individual app developers no longer need to replicate the common functionality elements that do not directly differentiate them in the market, and also frees them from the responsibility and costs of provisioning this baseline infrastructure needed for their apps to function. This lowers the entry barriers for app developers, who no longer need to be able to make irreversible investments in creating that functionality on a large scale. An app developer can develop a new app without starting from scratch and without reinventing the wheel in creating shared functionality that does not directly differentiate or provide utility for its end-users. The emphasis therefore shifts toward greater specialization among app developers (Iansiti and Levien, 2004, p. 149). However, creating and maintaining a competitive advantage requires attention to evolving platforms and apps in the face of rivals and copycats—the focus of Part III and beyond in this book.

Second, the reduction in initial financial outlays by app developers makes it financially feasible to attack long-tails of markets that would have otherwise been economically unviable. This potentially creates a win–win proposition for platform owners who often cannot economically target niche user bases in their market’s long-tail and for app developers who can have some assurance that the platform owner will not invade their niche. (When it does happen, how platform owners and app developers can tackle it is subsequently discussed in Part IV of this book.) The true potential of the platform therefore comes not just from its native capabilities but from the many serendipitous applications that end-users can put it to. This is driven largely by the diversity of apps that end-users can mix-and-match in use. The attractiveness of a platform to prospective end-users is therefore influenced by the availability and diversity of apps that complement it. This creates a natural alignment between the vested self-interests of app developers and the platform owner.

4.2.2 Market access

Platforms potentially offer app developers access to existing markets that would have been inaccessible to an app developer working in isolation. App developers are often like mom-and-pop stores, but the market potential that platforms can open up to them is unprecedented as the popular ones sell millions, if not billions, of copies. Platforms can do this by making it easier for prospective consumers of the app to find it and to cost-effectively acquire and deploy it in their own instantiations of the ecosystem. Platforms can make it easier for a potentially large set of platform users to find complementary apps. Software production involves sharp economies of scale: The initial copy of an app requires a substantial investment to produce but subsequent copies can be costlessly created and distributed. Therefore, an app developer has strong incentives to make the investment only when there exists a prospective pool of buyers that is sufficiently large for the app developer to break even. Therefore, copies of an app sold after the breakeven point (i.e., where revenues from copy sales balance out the app developer’s cost of producing the app) largely represent profits. Without the platform providing access to a prescreened pool of prospective customers, it would be much harder for an app developer to be found by the same customers. As a platform’s user base grows in sheer numbers, across geographical markets, and across industry segments, so does the pool of prospective customers accessible to the app. The net effect of using a platform is the potential for expanding demand for the app developer’s work (Evans et al., 2006, p. 79). (Economists call these search costs.) However, once a willing customer finds the app, the app developer also incurs costs of actually selling and delivering the app. Economists call thesetransaction costs (Rochet and Tirole, 2006; Williamson, 1991), which are incurred during the transaction after a search by the customer has been completed. Platforms can potentially reduce such transaction costs. The most common among such mechanisms are a payment mechanism infrastructure, which are shared by all participants on both sides of the platform. The platform infrastructure can also lower app developers’ distribution costs.

4.3 End-Users

The value proposition of platforms for end-users is fourfold: (1) almost-perfect customization, (2) faster innovation with network benefits, (3) benefits of rivalry on the supply side of platforms, and (4) lower search costs and transaction costs.

4.3.1 Mix-and-match customization

Most products are designed with a mass market in mind, where the focus is on meeting the needs common to the average user. Any idiosyncratic needs of an end-user that are not shared with the average user are likely to go unmet. For example, most users would use email on a smartphone but very few users would need a bibliography management tool. Software-based platforms that have a large variety of complements available allow immense levels of customization to end-users’ unique needs from a platform. Mixing-and-matching apps deployed by an end-user on a platform allows for large-scale customization of the ecosystem to individual users’ diverse and unique needs. Platforms therefore can offer end-users the ability to get complex, highly customized bundles of product or service functionality from a platform. This user-driven bundling of apps with the platform to create a unique portfolio is different from a one-size-fits-all approach that has been mainstream in the software industry. (If a platform has a variety of apps available that users can readily integrate with it, the platform can be described as having high composability.)

4.3.2 Faster innovation and network benefits

Unlike buying a product whose features are likely to remain much like they were when an end-user purchased it, a platform can grow in its capabilities and functionality long after the end-user has adopted it. Like wine, a platform can appreciate in value in a competitive market after it has been adopted. Intraplatform competition among apps and interplatform competition among competing platforms delivers a faster rate of innovation that is likely to benefit the end-user most. This innovation dynamic can increase the value of adopting a platform dramatically over time. Both platform owners and app developers have strong incentives to increase the value of the platform to prospective end-users by exploiting network effects. The end-user is one of the primary beneficiaries of the consequences of this incentive. As platforms evolve through different stages of its lifecycle, as discussed in Chapter 2, the focus of competition can shift toward a race-to-the-bottom, price-based competition, which usually benefits end-users the most by lowering their out-of-pocket platform adoption costs.

4.3.3 Competition among rivals

Rival apps compete for end-users’ attention. Similarly, rival platforms compete with each other for end-users. This competition eventually rewards survival of the fittest. End-users benefit directly from this competition because it provides access to apps that survive the value that they offer vis-à-vis competing apps. End-users also benefit from competition among rival platforms, which rewards platforms that deliver the most value for money to end-users in the long run. Once a platform reaches a more mature stage of its evolutionary lifecycle (the post-dominant design phase), the focus of competition shifts toward price-based competition. This eventually lowers the ongoing costs of using the platform and increases their affordability to end-users.

4.3.4 Lower search and transaction costs

Platforms can potentially reduce end-users’ search costs—costs incurred by them prior to transacting with platform complementors. For example, end-users might need to ascertain the trustworthiness of an app supplier and the quality of an app. A platform can provide mechanisms for reducing such costs, for example, by aggregating reviews of past purchasers, screening and certifying apps, and by establishing itself as a trusted intermediary. Generally, reducing search costs involves the platform owner providing information about each side to the other side to facilitate screening. They can also reduce the costs incurred by the users during their transactions with app developers through platform-based transaction and exchange mechanisms.

4.4 Lessons learned

Software platforms offer distinctive value propositions for platform owners, app developers, and end-users. Each of these have distinctively different needs and motivations for participating in a platform ecosystem. Therefore, a platform-based business model must not only meet these distinctive needs but must also do so in a more compelling manner than a standalone product or service business model. A brief summary of the key points described in this chapter appears below.

• The value proposition for platform owners. Platforms enable platform owners to innovate on a scale that they could not by themselves. They do this by massively distributing innovation activities that would otherwise have to be done inhouse across a diverse pool of outsiders with strong market-based incentives, drive, and deeper expertise in narrow domains and market segments. This simultaneously allows the platform owner to do more of what it does best and sharpening its focus around what it perceives as its core competence. Doing this allows capturing of the underexploited long-tails of its core market, transferring the costs and risks of developing new innovations to app developers, and increasing the likelihood that the platform can evolve to competitively sustain in shifting market environments.

• The value proposition for app developers. Platforms enable app developers to use the baseline capabilities of the platform as the foundation for their own work. Instead of replicating the functionality that their apps share with other apps, their upfront investment is therefore limited to functionality that their apps do not share with others. This makes it economically viable to target long-tail markets that would otherwise have been difficult to justify targeting, and gives them the advantages of scale without the cost of ownership by piggybacking on the platform. Platforms also provide access to an existing pool of customers, who can more easily find the app developer’s work and more efficiently transact with them. Therefore, they reduce both search costs and transaction costs between app developers and their prospective customers.

• The value proposition for end-users. The primary value proposition of platforms for end-users is that they can more uniquely customize their instantiation of a platform to their idiosyncratic needs by mixing-and-matching from a diverse pool of apps that augment the utility of a platform. This resembles mass customization of a product or service with a customer segment of one customer. End-users also benefit from the accelerated pace of innovation around their investment in the platform, with the prospects of increasing value over time as well as network effects that are also in the best interests of platform owners and app developers in competitive platform markets. Finally, platforms lower search costs and transaction costs associated with finding and acquiring apps relative to doing the same without a platform in the middle.

In the next chapter, we delve into architecture in platform ecosystems. We explore the architecture of the core platform and the micro architecture of individual apps that complement it. We also explore how such architectural choices affect the dependencies between the platform and apps, and how they facilitate partitioning and integration of innovation activity in platform ecosystems.

References

1. Dougherty D, Dunne D. Organizing ecologies of complex innovation. Organ Sci. 2011;22(5):1214–1223.

2. Eisenmann T, Parker G, van Alstyne M. Strategies for two-sided markets. Harv Bus Rev. 2006;84(10):1–10.

3. Evans D, Schmalensee R. Catalyst Code. Boston, MA: Harvard Press; 2007.

4. Evans D, Hagiu A, Schmalensee R. Invisible Engines: How Software Platforms Drive Innovation and Transform Industries. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press; 2006.

5. Iansiti M, Levien R. Keystone Advantage: What the New Dynamics of Business Ecosystems Mean for Strategy, Innovation, and Sustainability. Boston, MA: Harvard Business Press; 2004.

6. Meyer M, Selinger R. Product platforms in software development. Sloan Manag Rev. 1998;40(1):61–74.

7. Rochet J, Tirole J. Two-sided markets: a progress report. RAND J Econ. 2006;37(3):645–667.

8. Williamson OE. Comparative economic organization: the analysis of discrete structural alternatives. Adm Sci Q. 1991;36(2):269–296.

9. Williamson P, De Meyer A. Ecosystem advantage: how to successfully harness the power of partners. Calif Manag Rev. 2012;55(1):24–46.

*“To view the full reference list for the book, click here or see page 283.”