PRACTICAL EMPATHY: FOR COLLABORATION AND CREATIVITY IN YOUR WORK (2015)

CHAPTER 1

Business Is Out of Balance

Data and Analytics Take Priority

What Makes a Person Tick?

Rebalance Your Organization with Empathy

Here’s the situation: most organizations are out of balance, but they don’t know it. They do know that creative ideas are important. They know that strong collaboration forges better solutions and execution. But they still scramble to make both creativity and collaboration produce a more reliable return on investment in their product development and operations. No matter how many agencies and management consultants they hire, no matter how many promising experts they bring on board, things still don’t go as beautifully as they hoped.

At a certain level, you know opportunities exist to enrich what you are creating and improve how people in the organization work together. But you’ve seen how reality gets messy and how your leaders don’t always make the decisions you’d hoped for. Improvements you’re trying to make for the good of other people aren’t happening. You hear similar stories from your peers, and it seems to all come down to one reason: you’re not being heard. You keep repeating what you know to be important, but nothing seems to improve.

A significant portion of this failure can be assigned to each person in the organization, from the very top of the hierarchy to the very bottom. Each person has, to one degree or another, a cloudy awareness of his own motivations and guiding principles. Each person has, in one way or another, failed to explore the deeper currents of reasoning in the people around him. Each person has spoken but failed to listen. It’s true that awareness of other people’s perspectives allows you to develop much stronger solutions together. Knowing someone’s perspective involves empathy. Empathy requires listening. It is empathy that will have a huge impact on how you work. It’s empathy that will bring balance to your business.

Data and Analytics Take Priority

Within most organizations, attempts to improve the services they create seem to follow traditional production and efficiency paths. Leaders use metrics to measure their confidence in a new idea so that business decisions are “based on solid data.” Analytics prove that specific things happened, like the findings from dating organization OkCupid about stated age preferences versus actual contacts with potential dates. “35-year-old heterosexual men ... typically search for women between the ages of 24 and 40 ... yet in practice they rarely contact anyone over 29.”1 The president of the company decided to use the data sitting on his servers “for direct introspection,”2 making conclusions about behavior by inference rather than by asking about people’s actual guiding principles. (And simultaneously adding to the heated debate about companies using member data for any purpose they choose.)

Organizations declare themselves to be “data-driven,” “evidence-based,” and even “engineering-focused” as a way of showing how reliable they are to potential investors, partners, shareholders, and customers. These numeric measurements tell the story of what is happening in myriad ways. There are rings and rings of data around what has happened, when it happened, how it happened, and who participated from where. For example, Amazon has mountains of quantitative data about who purchases what and when. They also have the resources to pick through these numbers and find places where they want to ask, “Why? What were those people actually thinking?” And they can go ask those people. But not many organizations have the resources or the awareness to go find out the story of why.

What is the story of why?

The story of why is about the purpose a person has for doing something. For example, you don’t just open a savings account to save money for a big holiday. You open a savings account because you’re thrilled that you’re finally in the right position to actually follow your dream, the one you had since you were 12, about studying ancient cultures and going on an archaeological dig. Your motivation feels much different than saving for a car or a house. A house and a car are things your culture says you ought to save for; this holiday is your passion, not anyone else’s. You make your contributions to the account differently. If the bank only knew why you were saving, it could give you better support than deducting a set amount from each paycheck or making an announcement on social media for you to try to pressure you to “own your goal.” If the bank knew, it could maybe allow an external service to move $15 from your checking account to your savings account based on a trigger, such as when you favorite any articles with the word “archaeology” in them. But the bank is stuck in its own perception of saving money for a goal.

Product strategy may have something to do with technology, but it has everything to do with people. Comprehending the human half of the picture is one of the major aspects missing from providing any service or product. The human half of the picture is an underlying foundation for creativity.3 It defines areas you can explore. Unfortunately, you can’t force creativity down a rational, numeric path; it is well documented as a right-brained activity. This is why organizations need to understand the story of why. If the bank only knew why you’re doing what you’re doing, it could use your story as real data to get creative about supporting you—and others driven by a similar passion.

Immature Data Practices

Contemporary uses of data are immature. People within organizations try hard to apply the numeric data they have collected, but their approaches don’t have the benefit of decades of experience. Part of the reason is that people are still struggling to grasp in a useful way the overwhelming amounts of data that the digital world can produce. So because of this, many organizations slide back into a comfortable routine. Instead of leaps of progress, they tend to focus on linear improvements in transaction conversion and on copying what other organizations are doing. Instead of exploring the actual reasons behind the numeric trends, organizations simply twist numeric metrics into hyperbole to grab market attention.4

Additionally, when organizations try to leverage the data they have to affect the human side of the picture, they often take a childish approach, improving the links to social media, for instance, but not focusing on anything deeper. It’s like the desire to show that “we use the data” is more powerful than using the data for real.5

Painting a Picture with Only One Color

People at your organization may think the story of why is not as solid as numeric data. Most professionals understand that people are not reducible to metrics and numbers, yet when they introduce qualitative methods to balance out the numbers, they get push-back.

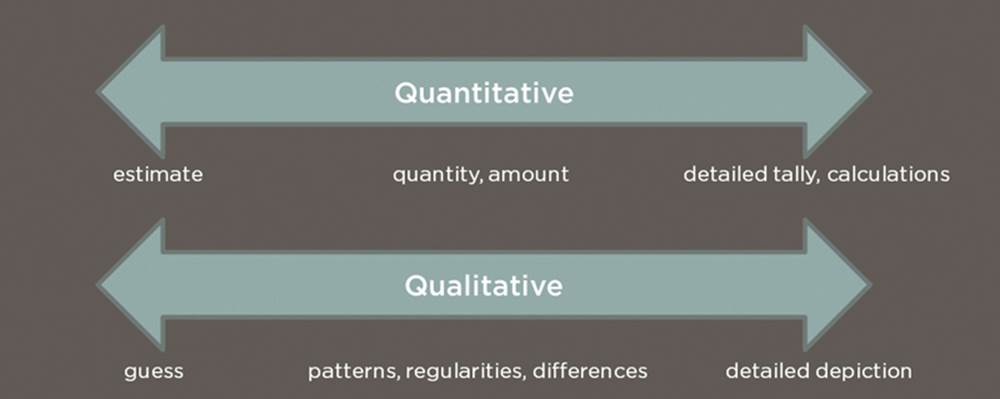

Here’s why they’re wrong. Unfortunately, the common assumption is that the qualitative and quantitative data are two extremes of the same spectrum (see Figure 1.1). Qualitative is suspected as a weaker, less-defined extreme. Quantitative and qualitative are not opposite ends of the same spectrum. They are two different spectrums.6 They measure two different things. Quantitative measures the numeric amount of something, and can run from estimates at one end of the spectrum to detailed calculations on the other. Qualitative represents patterns in data, often in terms of words instead of numbers, and can run from guesses at one end of the spectrum to detailed depictions at the other.

Humans describe their reasoning with words. Reasoning cannot be measured with numbers. But it can be analyzed for consistency and affinity. Qualitative and quantitative data are two different parts of the whole story. There are other systems in addition to these two, such as an emotional spectrum, or the spectrum of a certain demographic such as age. To use only one spectrum is to paint a picture with only one color.

FIGURE 1.1

Be ready to recognize if people in your organization perceive quantitative data as “solid” and qualitative data as “soft.” Both have valid and soft ends of their spectrums.

Abuse of Scientific Terminology

Another aspect of this fascination with the solidity of numbers is that people use (and abuse) scientific-sounding words in order to persuade people. Half the time people don’t even realize they are using the words for persuasion. This vocabulary has been used for decades in marketing, news, health, sports, and in the way that executives and leaders speak. People within organizations toss off phrases like, “Studies show that ...” and “Our tests verify ....” Rarely do these phrases actually indicate that a scientific process was followed. There was no hypothesis, no experiments disproving or supporting the premise, no alternative measurements and comparisons, no looking up similar studies that other people have done. No one outside the group tries to reproduce the results to make sure the conclusion is correct. So it’s not really science, but the vocabulary is pervasive. People respond to it.

For instance, if a decision-maker at your organization feels uncertain about the potential of an idea, he might ask you for “proof”—for numbers to clarify what decision he should make. You might conduct a quick survey, which feels scientific. Yet the results are only used to make people feel comfortable about heading in a certain direction. The results usually favor whatever you intend, of course, because it’s devilishly hard to write a survey that doesn’t represent your own perspective. Moreover, you’re converting people’s answers into numbers and ignoring the words. These converted numbers simply hoodwink everyone into feeling more confident.

Once you’re aware of it, you’ll hear and see scientific terminology everywhere. For example, as shown in Figure 1.2, a gym attracts customers with the phrase “sports health science.” The phrase seems to come directly from the name of a collegiate degree. There is probably legitimate science going on in that industry, with studies about professional sports players and about sedentary populations, but you don’t go to this gym to access that science. You go to access a professional who will motivate you to work out.

FIGURE 1.2

A gym is a gym—but this one is better, because it gives you “sports health science!”

Constrained Collaboration

Collaboration is hindered by differences in perspective. Divisions within larger organizations often measure and describe components of the same data differently, which makes their interpretations different and confusing. Not only is the picture half-painted, but the part that does get painted is represented with dissimilar vocabulary and diagrams. The marketing group wants everybody to make decisions based on the customer marketing segments they’ve defined, but the software folks want to pursue features in support of the search analysis they’ve done. Everybody’s busy explaining to each other how their perspective works—their definitions, vocabulary, and methods. Or worse, they’re ignoring other people’s perspectives or questioning their intelligence. Collaboration is not the smoothly oiled process you wish it could be.

Self-Focused Progress

Organizations forget to look beyond their own activities. In contemporary organizations, the energy of product strategy, creativity, and collaboration is focused only on efforts directly related to the things an organization delivers, rather than looking at people’s intents or purposes. Decision-makers try to understand employee, stakeholder, and customer “needs” and “requirements.” They focus on ways to get ahead of past failures and competition, how to keep up with external demands, or to predict future trends. They hope for a disruptive innovation.7 All these efforts are directed at how well the organization collaborates, puts together, and presents its solutions. They’re all derived from industrial roots.8

Decision-makers have very little solid knowledge about context beyond what they deliver. What’s going on in somebody’s mind? What is his motivation and larger purpose? There is very little effort put toward understanding the people involved. A product (or market) strategy was put in place a while ago and seems to be a foregone conclusion. Organizations feed their creative process with metrics about how things work currently. Only small groups that are actively attempting to pivot away from a direction that has not provided the expected returns take the time to look beyond the horizon of what’s in place already.

Lack of Listening

Anytime moving parts are out of alignment, it causes friction, which can shake your organization apart. Friction causes wear and tear on the people who work there and the people you serve. Everyone genuinely wants to prove his worth, impress people with great ideas, or just plain old fix things. Most of the time professionals are so busy trying to contribute their ideas and get other people to change that they don’t realize they’ve spent zero time understanding those other people and listening to them. No one is listening because everyone thinks others need to understand what he has to say. Consequently, understanding what is going on in other people’s minds is the first step toward counterbalancing the fascination of numbers and familiar perspectives.

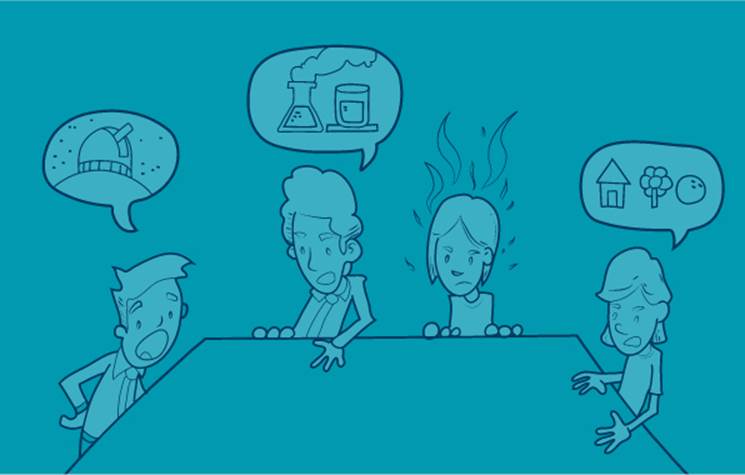

FIGURE 1.3

Everyone genuinely wants to contribute. No one is listening because everyone is talking at once.

What Makes a Person Tick?

Most organizations don’t try to understand people—there is too much variety and uniqueness in what drives decisions. For example, the reasons people get involved in a local civic issue depend upon the issue, the location, and the person. There could be 50 different reasons, which is far too many to address for any one organization—so the organization predefines two opinion groups to keep it simple and then assigns people to those groups.

• Open the park to professional baseball, for the benefit of local kids and local restaurants.

• Keep the park nonprofit so the constant crowds, litter, parking, or noise won’t despoil our neighborhood.

It turns out, though, that if you explore all the 50 reasons, there is more correspondence between the concepts than you’d expect. The deeper guiding principles that drive decision-making tend to cluster into just a few types of intentions.

• I intend to provide a service to a group, like kids, who need something more.

• I intend to make my neighborhood a safer/quieter/cleaner place to live.

• I intend to do something locally that will serve as a model and contribute to something larger.

• I intend to increase my property value.

• I intend to increase the profits to local small businesses so they can thrive.

You can see how the intent to increase my property value could be held by people in both opinion groups. Debating about how to fulfill some of these intentions might make better civic engagement than simply polarizing around the two opinions and whipping up a media firestorm.

The difficulty lies in getting past everybody’s habit of emphasizing opinions and using them to represent a person’s inner reasoning. This habit might be rooted in a mode of “hurriedness”—the desire of industrial cultures to accomplish more within each day.9 This desire results in quick but mostly shallow interactions that rely on assumptions you make about what the other person means. This speed also relies on shared cultural references or stereotypes that, even if meant in jest, symbolize philosophical stances. Saying “This project is on the road to nowhere; we are time-constrained, as always,” could actually mean you feel threatened by your manager, that you feel powerless to fix the process, or that you got distracted by a more exciting topic and didn’t actually make any progress on your assignment. Not many people take time to find out what’s underneath a statement like this, so communication remains shallow.

Some cultures fixate on preferences and opinions, letting those stand in for deeper reasoning. Other cultures tend to hold opinions more privately because it is considered impolite to thrust your opinion up against someone else’s publicly. When you look beyond preferences and opinions, you get a much more practical understanding of what a person is thinking. Going deeper than assumptions and opinions is what’s called empathy.

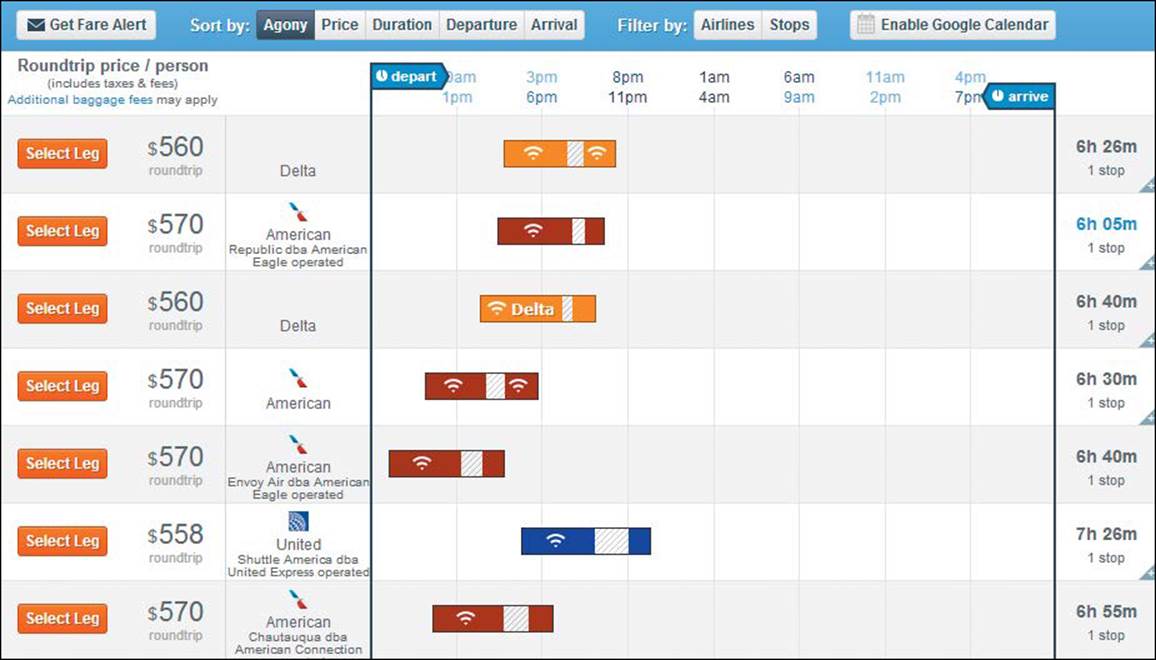

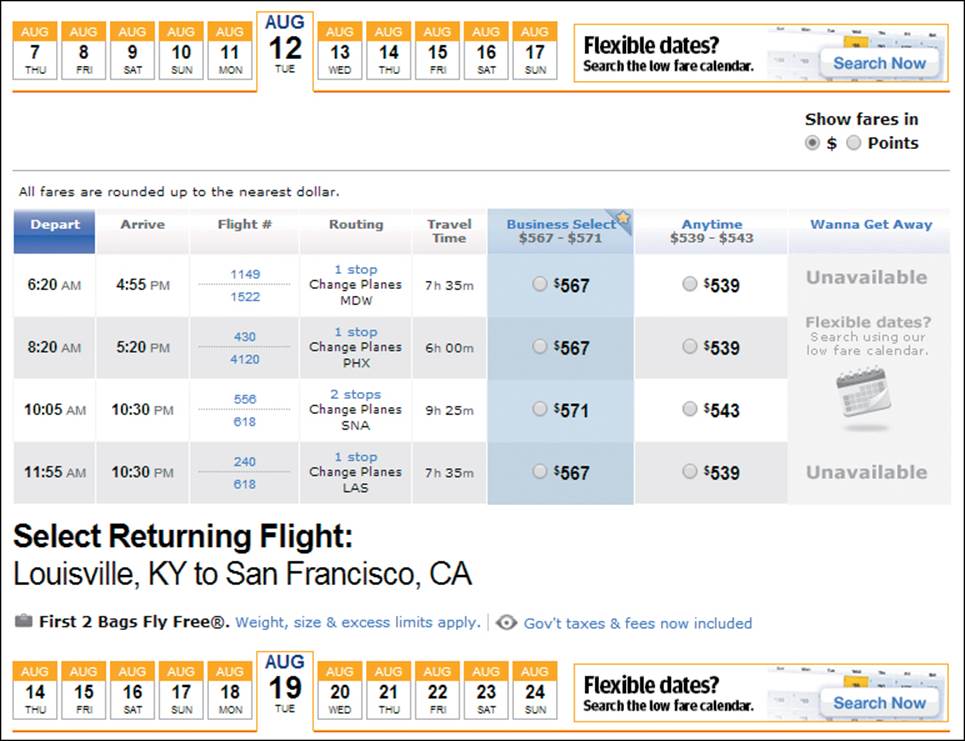

What does a deeper practical understanding look like for a business? Take the example of a service organization supporting external customers—say an airline and its passengers. Studying how someone books a flight, for example, uncovers the mechanics of looking for the cheapest, least painful routes. In Figure 1.4, they all appear to be painful.

FIGURE 1.4

Looking on Hipmunk for a flight from San Francisco to Louisville reveals that there are no direct flights. “Agony” already.

Going deeper and understanding why someone books a flight reveals some important reasoning. Based on many sessions listening to passengers, say the airline has divided them into four different sets of motivations and approaches, two of which are those who want the trip to be as quick as possible, and those who want to extend it. Some people feel obliged to take trips, while others look for opportunities to travel. Some people want to squeeze in other things to accomplish on the day they fly, get home to their toddlers as soon as possible, or sleep in their own beds. Others enjoy adding a weekend to a business trip to explore someplace new or to visit family. Although this behavior does change for certain individual trips, it appears to be a norm for most trips.

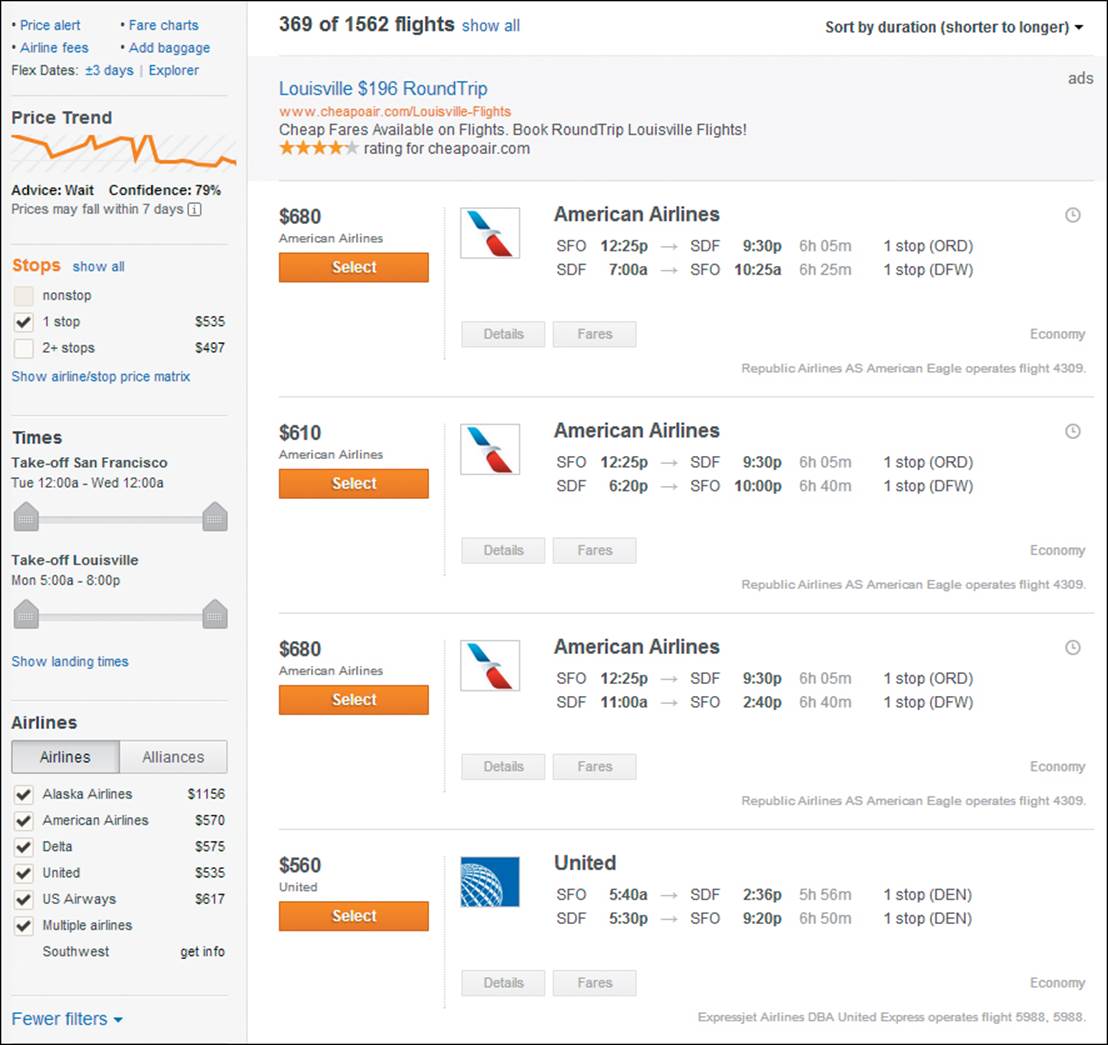

Passengers in both behavioral groups are forced to spend time searching for different combinations of flights, dates, and times that might fit their intentions. In Figure 1.5, passengers have to look through an overwhelming 369 options on Kayak to find that one magical, perfect flight. Additionally, since the destination requires a connection, passengers must consider the circumstances of each of the connecting airports. For example, the first five flights connect at airports known for delays during thunderstorm or snow season. In Figure 1.6, the airline encourages passengers to poke around on other dates just to make doubly sure there isn’t a better option.

FIGURE 1.5

Sorted by duration, there are still an overwhelming 369 number of options on Kayak to look through.

FIGURE 1.6

Southwest has a reasonably small number of options, but urges you to poke through the dates just to be sure there isn’t a better option.

Next, the airline reaches for its quantitative data: of these two behavioral types, which one spends the most money with the airline? Is there a reason to postpone working on a solution for one of the groups, in order to prioritize for the other? Maybe there’s a dip in spending during the winter on the part of the quick-trip types, or maybe they tend to take short-haul trips with no connections, which means less money spent overall.

In this example, it turns out there is no such correlation. The airline won’t prioritize one group over the other, but it will aim to create different approaches to better support each group.

To better support the quick-as-possible type of passenger, you could let him enter the dates and times of his must-attend events or places, either at home or away, and then offer three or four options instead of hundreds. This filtering down to just a few options based on the passenger’s situation and habits is what travel agents used to do for people. Additionally, you could show options outside your own service that fit the criteria better. Currently, none of the airlines or booking services shows you options that combine flights from airlines that are not partners. Even if there’s a chance of missing a connecting flight due to a delay, if the trade-off is a six-hour layover between flights, many people would be willing to take that risk.

Looking beyond the flight reservation tool itself allows the service organization to see opportunities to support someone more intimately. Imagine helping a passenger look at a custom list of options (including partners in rail and local ground transportation, say, for the trip-extenders) based on his travel philosophy, past trips, and activities scheduled on his calendar. Likewise, a different organization, like a bank, would be able to use the knowledge to aim its offers to earn miles toward free travel only to the trip-extenders. Sending these offers to the quick-trip types only telegraphs the message that the bank does not understand or care about this group’s motivations and reasoning. This additional data about what makes different people tick deeply affects the kinds of changes you make in your service offering.

Rebalance Your Organization with Empathy

Believe it or not, it’s not such a hard problem to get past the surface level. Once you get down to the deeper principles and reasoning that guides people’s actions, you can find solid, repeating patterns. These patterns will help you address specific concepts you had not acted in support of before. You can double-check a decision that was previously only based on numeric metrics. And your interactions with people can be improved. Communication with the intent to support your deeper understanding of someone can advance collaboration—both in your work group and across divisions. Empathy will play a role in rebalancing your organization’s clarity of purpose in the post-industrial, post-digital frontier creative age. You can be one of the people who pauses more often to listen and understand.

Taking time to be curious about people is key to the empathetic mindset.