PRACTICAL EMPATHY: FOR COLLABORATION AND CREATIVITY IN YOUR WORK (2015)

CHAPTER 3

![]()

Put Empathy to Work

Development Cycles

The Stages of Developing and Applying Empathy

The Logistics of Listening

When bringing the empathetic mindset into your practice at work, you need some structure. You need ways to explain the difference between developing and applying empathy, as well as how it hooks into your existing development and collaboration processes. You also need pointers on how to reach out to people and how to set up an interaction where you can earn their trust. These appear in this chapter.

Later in this book, there will be tips and guidelines, as well as some vocabulary to use, which will help you establish your capability to empathize with people in your work. The guidelines will also help you measure your improvement at applying empathy. The overall idea is to move beyond the lightning-strike epiphany form of emotional empathy, shifting to cognitive empathy, and turning that into harnessed electricity that helps your own practice, and that of your organization, run smoothly and dependably.

Development Cycles

When you create something, every project you undertake goes through cyclical stages of development as you mature and polish the ideas. One common representation of these stages is the Think-Make-Check cycle.

During the Think stage, you brainstorm ideas that could either become a solution or influence the solution you already have. All the details of developing the idea occur during the Make stage, even if that development is simply a sample or sketch of an idea.1 Then in the Check stage, the idea gets poked and prodded not only by the potential end customers (commonly referred to as “user research”), but also by the creators and the stakeholders.

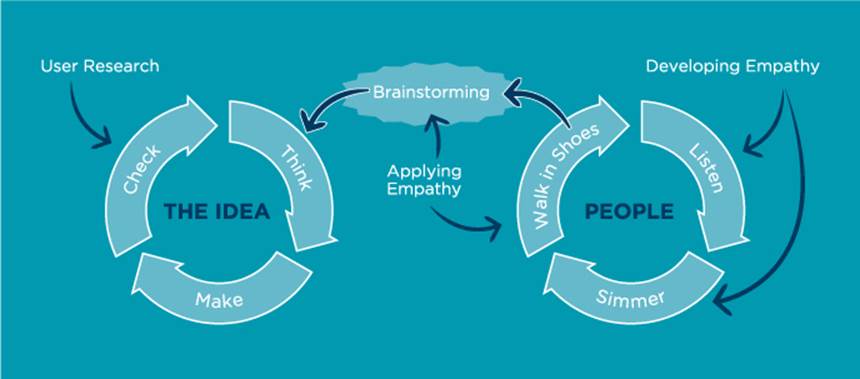

Typically, organizations focus hard on their development cycles, which means they spend most of their energy cycling around the ideas they have. The Think-Make-Check cycles all rotate around ideas or solutions. They do not rotate around people. If you’re going to balance out that focus on solutions, you can introduce a separate cycle of empathy that focuses on people and their purposes. In other words, study the problem space in addition to the solution space. This person-focused cycle will rotate more slowly than your development cycles, but you will always be reaching out, every few months, to people to add more understanding to your repository. Your understanding of the deeper reasoning and broader purpose of people will feed your empathetic mindset. Then it will be present in your mind during brainstorming—or during the Think stage of the cycle around an idea (see Figure 3.1).

FIGURE 3.1

When you create something, each project cycles around an idea you want to bring to fruition. Adding a parallel cycle that focuses on people brings much greater depth to your brainstorming.

The Stages of Developing and Applying Empathy

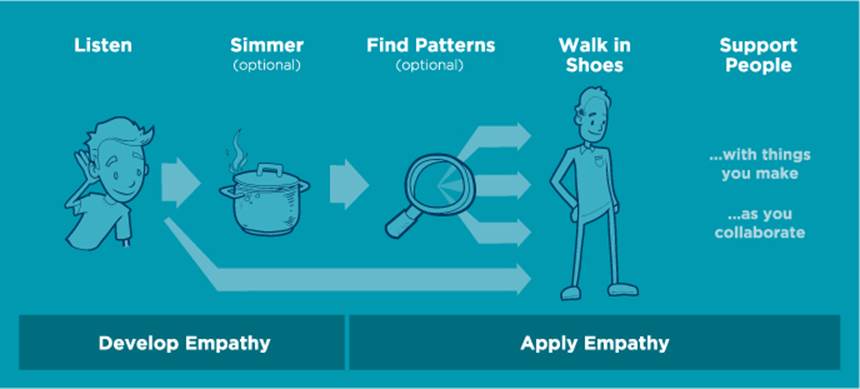

As you set out to adopt an empathic mindset at work, it might help to envision a set of stages that you pass through. The stages group into two parts: developing empathy and applying empathy. You cannot apply empathy before you have spent time developing it. You need one to do the other.

Developing empathy starts with listening, of course. Then there’s an optional period after listening during which you think through, reread, or summarize the things you heard. You let the information simmer, if you like, allowing yourself to build a much deeper, richer understanding of what you heard.

Types of Business Research

“User research,” where a solution is checked to see if it works for people who might “use” it, is one of many types of research done by organizations to guide decisions. There is also “market research,” where organizations seek to understand consumer preferences and trends, so they can craft their offerings to suit, or alternatively, where organizations assess the viability in the market of a new idea. There’s “competitive research,” where an organization seeks to understand the capabilities, both present and future, of competing organizations to possibly win customers away from them.

All the research projects that organizations perform, no matter which type of research it represents, tend to fall into two categories: evaluative or generative. Evaluative research seeks to judge how well something works for a person. Generative research seeks to collect knowledge about a person or context or market that can serve as a foundation for creating new ideas. The kind of empathy defined in this book is generative research.

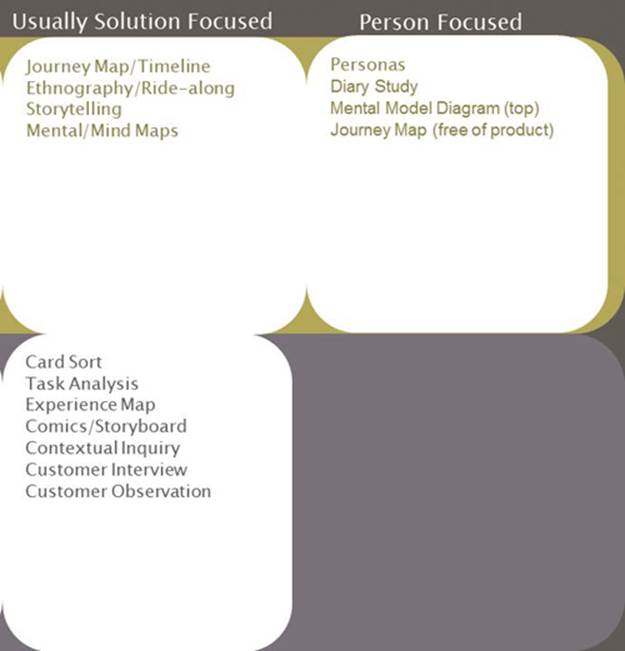

FIGURE 3.2

Most exploration in support of creative work is solution-focused. There is a need for more person-focused exploration.

For those who are involved with evaluative and generative research, there is one more distinction you may be interested in. Typically, all research that has to do with a “user” is really about the solution or idea that will be “used.” The word “feedback” disguises a similar meaning—feedback is hearing things about the solution or idea. Rarely does generative research focus only on a person, paying attention only to the person’s thoughts and reactions and purpose, as opposed to looking for opportunities to fit your idea into his life. Person-focused generative research is a powerful sibling to solution-focused research, telling you the story of why someone makes decisions the way he does (see Figure 3.2).

Applying empathy starts, in some contexts, by looking for patterns of thinking and decision-making and aggregating them across a whole set of people. In other contexts, like when you are trying to move fast, you skip this stage entirely. Either way, the next stage is to step into a person’s shoes and try on his reasoning processes (see Figure 3.3). The exercise is meant to help you decide about something you are creating, for example, a new hiring process for your division, or about some interaction with a person in your work, like when you face someone who seems to be obstructing your progress. These stages will be detailed in the next few chapters of this book.

FIGURE 3.3

The two parts of an empathetic mindset, developing and applying empathy, are distinct. They are intended to guide your decisions and actions in the things you create and the interactions you have with others.

Empathy is, ironically, often used for persuasion. In marketing, in politics, in the media—the purpose of understanding someone else is often to induce a change in his beliefs or behavior. This is not the only use of empathy. Empathy is also used to encourage growth or maturity in young people, teaching them to respect perspectives that are different than their own. Empathy is used to affect subject, tone, and vocabulary to be able to initiate communication with a person. Additionally, empathy is used literally to act like someone else, imagining how to behave in a series of situations.2 However, the application of empathy that has impact on your work is to use it in support of someone. Empathy in support is being willing to acknowledge another person’s intent and work with it, morphing your own intent because of the empathy you developed for the other person.

While you are developing empathy, what you learn is evergreen. People’s reasoning patterns do not change overnight. Patterns do not change as a result of tools and technology—mostly, only the frequency and speed of achieving a purpose changes. The knowledge you are building will last, foreseeably, the length of your career. Because the knowledge is long-lived, you don’t have to hurry through cycles of building it. It will always be there, and you can always add to it—even if a couple of years have passed by.

NOTE WHEN NOT TO SAY THE WORD “USER”

The word user is directly tied to a product, service, process, policy, or content. Indeed, you might say “patron,” “reader,” “guest,” “patient,” “passenger,” “member,” or any number of other nouns to describe a person who takes advantage of what you have created. It’s fine to use these nouns when applying empathy. But when you are in the stage of developing empathy, the person has no relation to what your organization delivers. The person is simply a human you are trying to understand more deeply. When developing empathy, avoid saying any of these “user” nouns. Say “person” or “human” or even the individual’s name instead.

The Logistics of Listening

There is a lot of flexibility with empathetic mindset listening. Here are some pointers. First, even though the word “listening” implies hearing someone, you can “listen” via written words. As long as you write back questions about what was written, to get a better idea of what lies underneath, writing is a perfectly acceptable way to “listen.”

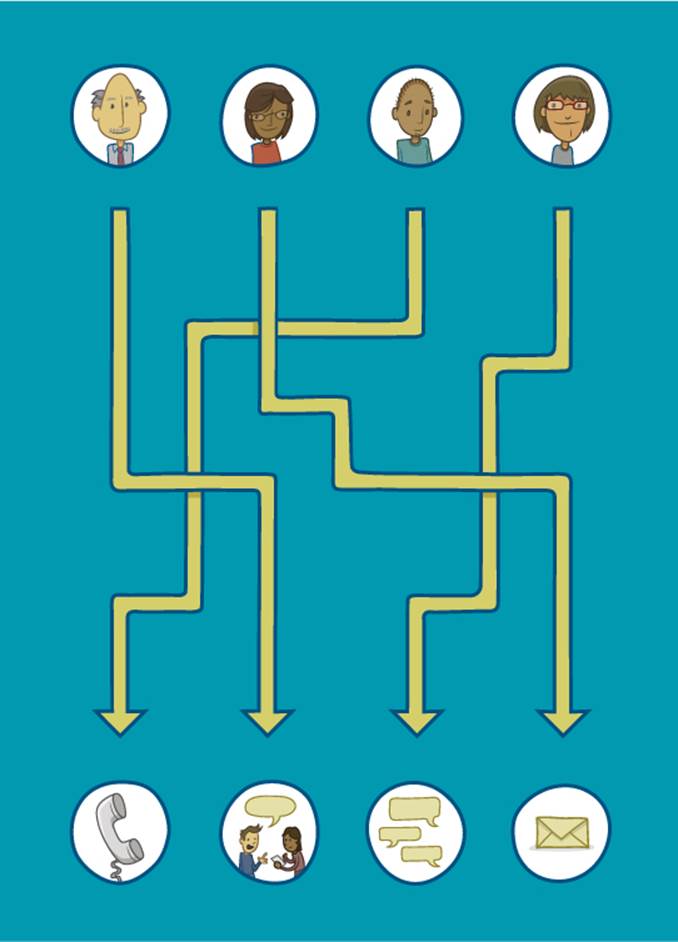

Ordinarily, though, you will listen by hearing someone speak. This listening implies synchronous speech, because you’ll want to go back and forth with the person in a conversation—talk, dig deeper, talk, dig deeper. You will connect with this other person face-to-face or remotely (seeFigure 3.4).

FIGURE 3.4

There is a lot of flexibility with listening. You can even “listen” via written words.

A Formal Listening Session

You can either drop into listening mode informally, during interaction you are having, say, in the hallway with a peer, or you can purposefully set up a time to listen to a person. If you set up a formal time, refer to the session either as “a conversation” or “a listening session.” The word “conversation” implies that dialogue will go back and forth, which isn’t strictly correct. But it’s a common enough word to describe what you are doing. Use “conversation” when setting up a session with the other person. In your own head, use the phrase “listening session.”3 This phrase attempts to get at the intention of following that person’s words, rather than contributing to the dialogue.

Just don’t think of a listening session as an interview. The word “interview” is so overloaded that when another person hears you say it, he is likely to be thinking of a different thing.

For formal sessions, you will necessarily go through the process of finding the right people to set up appointments with. You’ll want people who are comfortable describing things—skip those people with single-word answers. When you set up the appointment for a spoken listening session, you can mention the scope in advance, as well as any details you’d like about the project or your organization and the purpose of the listening session. For written sessions (essays with Q&A follow-up), you can do the same in your written introduction.

A formal listening session lends itself well to being recorded. A recording will make the next stage much easier, because you will be able to go back over what was said if you can’t remember it all. If you have a transcript made from the recording, then it is even easier to go back over what was said, and even search for certain words that you remember, so you can reacquaint yourself with the context. According to law in many countries, you must get a person’s permission to record the session. Verbal permission can be documented in the recording itself, for convenience. If a person unexpectedly does not want to be recorded, follow his wishes without complaint. You will still remember enough from the session for it to be worthwhile to continue.

Empathy Is Not an Interview

The word “interview” has so many meanings. Each interview type has a distinct purpose and format. So, to keep from confusing the meaning further, simply avoid the word, even though it’s true that listening sessions are a type of nondirected interview for the purpose of developing empathy.4

The English word “interview” can mean:

• A meeting between a potential employer and a candidate during which the employer tries to assess the skills and attitude of the candidate, and the candidate tries to decide if the job and coworkers are right for him

• A conversation that a radio, TV, studio, or panel host conducts with a guest for the purpose of entertaining or educating an audience with the guest’s answers

• The format in which a reporter collects statements from an expert or witness, with the potential to be used as quotes in his material

• The discussion a detective has with an expert or witness to gain an understanding of what might have truly occurred

• The way a design researcher understands how a person uses a product, service, content, or process, for the purpose of judging how well the item functions

• One format for a psychotherapy consultation

If you are engaged in a formal listening session via remote connection, you also have the opportunity to invite your peers to listen in. Again, according to law in most countries, you are required to ask permission for these peers to listen. These additional listeners must remain muted, but they can be connected via chat or shared documents for learning purposes or to exchange comments about what is said. Sometimes, when a person agrees to the additional listeners, he may be hesitant with his answers. Rarely does this hesitation last more than five minutes into the session, since the remote listeners are easily dismissed from his mind.

Why Is a Remote Connection Okay?

Among researchers, remote listening causes disagreement. Ethnographers lean toward observation as a superior method. Usability researchers cry out, “Get out of the building! Get in front of your users!” The prevailing sentiment is that in-person sessions provide richer information, because of body language and physical context. In-person sessions are praised as a way to help you understand little details a study participant wouldn’t think to report, or might feel inclined to report differently. For developing empathy, though, remote listening is equally as good. Depending on your own habits and comfort level, as well as the other person’s topics and context, remote listening is sometimes better than in person.

Remote listening is acceptable because of the phrase “get in front of your users!” For evaluative research—where people are using a solution or service—yes, get out into the real world. It can really deepen your understanding.5 However, developing empathy is not focused on a solution or experience. In a lot of cases, it’s not even research. It’s just you building your knowledge about how another person thinks his way toward a purpose. Even in the cases when you’re developing empathy with your organization’s customers—and it can be called research6—their purposes are much larger than any solution or experience your organization provides. You are exploring concepts with a person that have little to do with the use of any particular thing. The details reside completely within the person’s head, because you’re only exploring within the boundaries of the mind. Remote listening is perfect for connecting mind-to-mind.

Sometimes, it actually helps to have a remote connection. If you don’t feel like you have control over your facial expressions, or if you are afraid that aspects about the other person might inadvertently prejudice or distract you, then a remote connection will conveniently hide all of this.7Additionally, since you cannot see the other person’s environment, he will automatically include more descriptions of how his world affects his thinking in his speech. These descriptions give you more material to dig into. Because he is free of your potentially unskilled body language, he will feel free to honestly discuss his thinking on sensitive subjects, such as health or finance. Often, the person will undergo a little self-discovery as he makes sense of his interior thoughts in a way he hadn’t thought of before. The distance created by a remote connection gives you and the other person both space to be comfortable.

One at a Time

The only inflexible rule about listening is that you should listen to one person at a time. You need to concentrate, and you need time to explore this person’s deeper reasoning. And, if the other person is going to tell you his innermost thinking, he needs the opportunity to develop trust in you. There can’t be other people telling their stories at the same time. If there are other people, as is true for focus group studies, some members of a group will end up deferring to others, or even adopting their beliefs in an effort to fit in or make the session go more smoothly. You really don’t want group dynamics interfering with the depth of conversation you want to reach. So, listen to only one person at a time.

No List of Questions

If you have any familiarity with interviews, even if you reach back to your school journalism days, you know that great effort is put into forging a predetermined list of questions. But a listening session is not an interview. Throw out your list of questions. Don’t put effort into researching what topics might come up. Any forethought will distract you from what the other person will tell you. You’ll do fine without a list, just like you do well enough without a list of questions at conferences, parties, and weddings. There are more guidelines about how to run a formal listening session without a list of questions in the next chapter.

Remote Coaching

As a life coach, Zô De Muro has 25 years of experience listening to his clients as they explore how to make big changes in their behaviors to reach their health goals. Over time, he has come to the conclusion that the Observer Effect8 is most obvious in face-to-face sessions. “Clients often want to please coaches, so they’ll say things to elicit a positive reaction,” Zô says. To minimize the Observer Effect, Zô prefers to conduct client sessions by phone. The client can then focus on himself. “Having the physical distance allows clients to open up more completely.”

Zô has learned to pay close attention to a person’s voice. He listens to inflection, tone, speed, pitch, cadence, and pauses. Each has a spectrum of meanings—especially the silences. “Altogether, listening closely to a client’s voice tells me tons of information.”

Lastly, Zô wears hearing aids as a part of his everyday life. He embraces the technology that boosts a hearing aid when on a call. “When I’m on the phone, I can crank up my headset, so I hear nuances that would be lost in person because of ambient noise.”

Keep It Simple

The best part about listening is that you don’t have to be “a good facilitator” or a “skilled interviewer” to develop empathy. It’s more about just being yourself, in curiosity mode. Kids can do it. What it takes is the ability to let go of your own thoughts and really absorb what you hear.

So, now you’re ready to get into the details of this new way of listening. The next chapter contains a lot of tips. Give yourself space to take it all in; your mind will take a few months to absorb everything. Practicing these tips in tiny daily listening sessions will help you gain competence.

Developing empathy means focusing only on the peaks and valleys of what the person tells you, nothing else.