Product Details Lean Enterprise: How High Performance Organizations Innovate at Scale (2015)

Part I. Orient

The purpose of an organization is to enable ordinary human beings to do extraordinary things.

Peter Drucker

Shareholder value is the dumbest idea in the world…[it is] a result, not a strategy…Your main constituencies are your employees, your customers, and your products.8

Jack Welch

We begin by offering our definition of an enterprise: “a complex, adaptive system composed of people who share a common purpose.” We thus include non-profits and public sector companies as well as corporations. We will go into more detail on complex, adaptive systems in Chapter 1. However, the idea of a common purpose known to all employees is essential to the success of an enterprise. A company’s purpose is different from its vision statement (which describes what an organization aspires to become) and its mission (which describes the business the organization is in). Graham Kenny, managing director of consultancy Strategic Factors, describes the purpose of an organization as what it does for someone else, “putting managers and employees in customers’ shoes.”9 He cites as examples the Kellogg food company (“Nourishing families so they can flourish and thrive”) and the insurance company IAG (“To help people manage risk and recover from the hardship of unexpected loss”), to which we add our favorite example: SpaceX, “founded in 2002 by Elon Musk to revolutionize space transportation and ultimately make it possible for people to live on other planets.”10

Creating, updating, and communicating the company’s purpose is the responsibility of the enterprise’s executives. Their other responsibilities include creating a strategy through which the company will achieve its purpose and growing the culture necessary for that strategy to succeed. Both strategy and culture will evolve in response to changes in the environment, and leaders are responsible for directing this evolution and for ensuring that culture and strategy support each other to achieve the purpose. If leaders do a good job, the organization will be able to adapt, to discover and meet the changing customer needs, and to remain resilient to unexpected events. This is the essence of good governance.

In the context of corporations, the idea of a common purpose other than profit maximization may seem quaint. For many years, the conventional wisdom held that corporate executives should focus on maximizing shareholder value, and this goal was reinforced by compensating executives with stocks.11 However, these strategies have a number of flaws. They create a bias towards short-term results (such as quarterly earnings) at the expense of longer-term priorities such as developing the capabilities of employees and the relationships with customers. They also tend to stifle innovation by focusing on tactical actions to reduce costs in the short term at the expense of riskier strategies that have the potential to provide a higher payoff over the lifetime of the organization, such as research and development or creating disruptive new products and services. Finally, they often ignore the value of intangibles, such as the capabilities of employees and intellectual property, and externalities such as the impact on the environment.

Research has shown that focusing only on maximizing profits has the paradoxical effect of reducing the rate of return on investment.12 Rather, organizations succeed in the long term through developing their capacity to innovate and adopting the strategy articulated by Jack Welch in the above epigraph: focusing on employees, customers, and products. Part I of this book sets out how to achieve this.

8 http://on.ft.com/1zmWBMd

9 http://bit.ly/1zmWArB

10 In the copious free time left over from SpaceX, Musk co-founded Tesla Motors along with “a group of intrepid Silicon Valley engineers who set out to prove that electric vehicles could be awesome.”

11 This strategy originates from Jensen and Meckling’s “Theory of the Firm” (Journal of Financial Economics, 3, no. 4, 1976).

12 John Kay’s Obliquity (Penguin Books) provides detailed research and analysis supporting what he describes as the “profit-seeking paradox.”

Chapter 1. Introduction

It’s possible for good people, in perversely designed systems, to casually perpetrate acts of great harm on strangers, sometimes without ever realizing it.

Ben Goldacre

On April 1, 2010, California’s only motor vehicle plant, New United Motor Manufacturing, Inc. (NUMMI), shut down. NUMMI, which opened in 1984, had been a joint venture between GM and Toyota. Both companies stood to benefit from the partnership. Toyota wanted to open a plant in the US to escape import restrictions threatened by the US Congress in reaction to the inexorably falling market share of US auto manufacturers. For GM, it was a chance to learn how to build small cars profitably and to study the Toyota Production System (TPS) that had enabled Japanese auto manufacturers to consistently deliver the highest quality in the industry at costs that undercut those of US manufacturers.13

For the joint venture, GM chose the site of their shuttered Fremont Assembly plant. GM’s Fremont plant was one of their worst in terms of both the quality of the cars produced and the relationship between managers and workers. By the time the plant closed in 1982, labor relations had almost completely broken down, with workers drinking and gambling on the job. Incredibly, Toyota agreed to the demand of United Auto Workers’ negotiator Bruce Lee to rehire the union leaders from Fremont Assembly to lead the workforce at NUMMI. The workers were sent to Toyota City in Japan to learn the TPS. Within three months, the NUMMI plant was producing near-perfect quality cars—some of the best quality in America, as good as those coming from Japan—at much lower cost than Fremont Assembly had achieved. Lee had been right in his bet that “it was the system that made it bad, not the people.”

Much has been written about the TPS, but one recurring theme, when you listen to the Fremont Assembly workers who ended up at NUMMI, is teamwork. It might seem banal, but it was an incredibly powerful experience for many of the UAW employees. The TPS makes building quality into products the highest priority, so a problem must be fixed as soon as possible after it’s discovered, and the system must then be improved to try and prevent that from happening again. Workers and managers cooperate to make this possible. The moment a worker discovers a problem, he or she can summon the manager by pulling on a cord (the famous andon cord). The manager will then come and help to try and resolve the problem. If the problem cannot be resolved within the time available, the worker can stop the production line until the problem is fixed. The team will later experiment with, and implement, ideas to prevent the problem from occurring again.

These ideas—that the primary task of managers is to help workers, that workers should have the power to stop the line, and that they should be involved in deciding how to improve the system—were revolutionary to the UAW employees. John Shook, the first American to work in Toyota City, who had the job of training the NUMMI workers, reflects that “they had had such a powerful emotional experience of learning a new way of working, a way that people could actually work together collaboratively—as a team.”

The way the TPS works is in sharp contrast to the traditional US and European management practice based on the principles of Frederick Winslow Taylor, the creator of scientific management. According to Taylor, the job of management is to analyze the work and break it down into discrete tasks. These tasks are then performed by specialized workers who need understand nothing more than how to do their particular specialized task as efficiently as possible. Taylorism fundamentally thinks of organizations as machines which are to be analyzed and understood by breaking them down into component parts.

In contrast, the heart of the TPS is creating a high-trust culture in which everybody is aligned in their goal of building a high-quality product on demand and where workers and managers collaborate across functions to constantly improve—and sometimes radically redesign—the system. These ideas from the TPS—a high-trust culture focused on continuous improvement (kaizen), powered by alignment and autonomy at all levels—are essential to building a large organization that can adapt rapidly to changing conditions.

A key part of the success of the TPS is in its effect on workers. Taylorism makes workers into cogs in a machine, paid simply to perform preplanned actions as quickly as possible. The TPS, instead, requires workers to pursue mastery through continuous improvement, imbues them with a higher purpose—the pursuit of ever-higher levels of quality, value, and customer service—and provides a level of autonomy by empowering them to experiment with improvement ideas and to implement those that are successful.

Decades of research have shown that these intrinsic motivators produce the highest performance in tasks which require creativity and trial-and-error—where the desired outcome cannot be achieved simply by following a rule.14 In fact, extrinsic motivators such as bonuses and rating people in performance reviews actually decrease performance in such nonroutine work.15 Rick Madrid, who worked at the Fremont plant both before and during the NUMMI era, says of the TPS that “it changed my life from being depressed, bored—and like my son said, it changed my attitude. It changed me all for the better.” Giving people pride in their work rather than trying to motivate them with carrots and sticks is an essential element of a high-performance culture.16

Although the principles at the heart of the TPS might seem relatively straightforward, they were very hard to adopt. Indeed, GM utterly failed in taking what it had achieved at NUMMI and reproducing it in other GM plants. Some of the biggest obstacles were changes to the organizational hierarchy. The TPS does away with the concept of seniority in which union workers are assigned jobs based on how many years of service they have, with the best jobs going to the most senior. Under the TPS, everybody has to learn all the jobs required of their team and rotate through them.The TPS also removes the visible trappings and privileges of management. Nobody wore a tie at the NUMMI plant—not even contractors—to emphasize the fact that everybody was part of the same team. Managers did not receive perks accorded to them at other GM plants, such as a separate cafeteria and car park.

Finally, attempts to improve quality ran up against organizational boundaries. In the TPS, suppliers, engineers, and workers collaborate to continuously improve the quality of the parts and to make sure workers have the tools they need to do their job. This worked at NUMMI because the engineers were in-house and the parts came from Japanese suppliers that had a collaborative relationship with Toyota. In the US supply chain, things were different. If the parts that came in to GM assembly plants were of poor quality, or didn’t fit, there was simply no mechanism to fix the problem.

Ernie Schaefer, manager of GM’s Van Nuys plant—which faced many of the same problems as Fremont Assembly—describes what was different about NUMMI: “You can see a lot of things different. But the one thing you don’t see is the system that supports the NUMMI plant. I don’t think, at that time, anybody understood the large nature of this system. General Motors was a kind of throw it over the wall organization. Each department, we were very compartmentalized, and you design that vehicle, and you’d throw it over the wall to the manufacturing guys.” This is the legacy of a Taylorist management approach. The TPS exists—and can only succeed—within an ecosystem of organizational culture, supplier relations, financial management, HR, and governance designed around its philosophy.

GM tried to implement the TPS at Van Nuys, but failed. Workers and managers rebelled in the face of changes in status and behavior that were required of them, despite the threat of closure (which was ultimately carried out). According to Larry Spiegel, a veteran of NUMMI who had been sent to Van Nuys to help implement the TPS, people at the plant simply didn’t believe the threats to shut it down: “There were too many people convinced that they didn’t need to change.”

This lack of urgency acted as a barrier to adoption across GM—and is perhaps the biggest obstacle to organizational change in general.17 The US division of GM took about 15 years to decide they needed to seriously prioritize implementing the TPS, and a further 10 years to actually implement it. By this time any competitive advantage they could have gained was lost. GM went bankrupt and was bailed out by the US government in 2009, at which point it pulled out of NUMMI. Toyota shut down the NUMMI plant in 2010.

The story of NUMMI is important because it illustrates the main concern of this book—growing a lean enterprise, such as Toyota—and many of the common obstacles. Toyota has always been very open about what it is doing, giving public tours of its plants, even to competitors—partly because it knows that what makes the TPS work is not so much any particular practices but the culture. Many people focus on the practices and tools popularized by the TPS, such as the andon cords. One GM vice president even ordered one of his managers to take pictures of every inch of the NUMMI plant so they could copy it precisely. The result was a factory with andon cords but with nobody pulling them because managers (following the principle of extrinsic motivation) were incentivized by the rate at which automobiles—of any quality—came off the line.

A Lean Enterprise Is Primarily a Human System

As the pace of social and technological change in the world accelerates, the lean approach pioneered by Toyota becomes ever more important because it sets out a proven strategy for thriving in uncertainty through embracing change. The key to understanding a lean enterprise is that it is primarily a human system. It is common for people to focus on specific practices and tools that lean and agile teams use, such as Kanban board, stand-up meetings, pair programming, and so forth. However, too often these are adopted as rituals or “best practices” but are not seen for what they really are—countermeasures that are effective within a particular context in the pursuit of a particular goal.

In an organization with a culture of continuous improvement, these countermeasures emerge naturally within teams and are then discarded when they are no longer valuable. The key to creating a lean enterprise is to enable those doing the work to solve their customers’ problems in a way that is aligned with the strategy of the wider organization. To achieve this, we rely on people being able to make local decisions that are sound at a strategic level—which, in turn, relies critically on the flow of information, including feedback loops.

Information flow has been studied extensively by sociologist Ron Westrum, primarily in the context of accidents and human errors in aviation and healthcare. Westrum realized that safety in these contexts could be predicted by organizational culture, and developed a “continuum of safety cultures” with three categories:18

Pathological organizations are characterized by large amounts of fear and threat. People often hoard information or withhold it for political reasons, or distort it to make themselves look better.

Bureaucratic organizations protect departments. Those in the department want to maintain their “turf,” insist on their own rules, and generally do things by the book—their book.

Generative organizations focus on the mission. How do we accomplish our goal? Everything is subordinated to good performance, to doing what we are supposed to do.

These cultures process information in different ways. Westrum observes that “the climate that provides good information flow is likely to support and encourage other kinds of cooperative and mission-enhancing behavior, such as problem solving, innovations, and interdepartmental bridging. When things go wrong, pathological climates encourage finding a scapegoat, bureaucratic organizations seek justice, and the generative organization tries to discover the basic problems with the system.” The characteristics of the various types of culture are shown in Table 1-1.

|

Pathological (power-oriented) |

Bureaucratic (rule-oriented) |

Generative (performance-oriented) |

|

Low cooperation |

Modest cooperation |

High cooperation |

|

Messengers shot |

Messengers neglected |

Messengers trained |

|

Responsibilities shirked |

Narrow responsibilities |

Risks are shared |

|

Bridging discouraged |

Bridging tolerated |

Bridging encouraged |

|

Failure leads to scapegoating |

Failure leads to justice |

Failure leads to enquiry |

|

Novelty crushed |

Novelty leads to problems |

Novelty implemented |

|

Table 1-1. How organizations process information |

||

Westrum’s typology has been extensively elaborated upon, and has a visceral quality that will appeal to anybody who has worked in a pathological (or even bureaucratic) organization. However, some of its implications are far from academic.

In 2013, PuppetLabs, IT Revolution Press, and ThoughtWorks surveyed 9,200 technologists worldwide to find out what made high-performing organizations successful. The resulting 2014 State of DevOps Report is based on analysis of answers from people working in a variety of industries including finance, telecoms, retail, government, technology, education, and healthcare.19 The headline result from the survey was that strong IT performance is a competitive advantage. Analysis showed that firms with high-performing IT organizations were twice as likely to exceed their profitability, market share, and productivity goals.20

The survey also set out to examine the cultural factors that influenced organizational performance. The most important of these turned out to be whether people were satisfied with their jobs, based on the extent to which they agreed with the following statements (which are strongly reminiscent of the reaction of the NUMMI workers who were introduced to the Toyota Production System):

§ I would recommend this organization as a good place to work.

§ I have the tools and resources to do my job well.

§ I am satisfied with my job.

§ My job makes good use of my skills and abilities.

The fact that job satisfaction was the top predictor of organizational performance demonstrates the importance of intrinsic motivation. The team working on the survey wanted to look at whether Westrum’s model was a useful tool to predict organizational performance.21 Thus the survey asked people to assess their team culture along each of the axes of Westrum’s model as shown in Table 1-1, by asking them to rate the extent to which they agreed with statements such as “On my team, failure causes enquiry.”22 In this way, the survey was able to measure culture.

Statistical analysis of the results showed that team culture was not only strongly correlated with organizational performance, it was also a strong predictor of job satisfaction. The results are clear: a high-trust, generative culture is not only important for creating a safe working environment—it is the foundation of creating a high-performance organization.

Mission Command: An Alternative to Command and Control

High-trust organizational culture is often contrasted to what is popularly known as “command and control”: the idea from scientific management that the people in charge make the plans and the people on the ground execute them—which is usually thought to be modelled on how the military functions. In reality, however, this type of command and control has not been fashionable in military circles since 1806 when the Prussian Army, a classic plan-driven organization, was decisively defeated by Napoleon’s decentralized, highly motivated forces. Napoleon used a style of warknown as maneuver warfare to defeat larger, better-trained armies. In maneuver warfare, the goal is to minimize the need for actual fighting by disrupting your enemy’s ability to act cohesively through the use of shock and surprise. A key element in maneuver warfare is being able to learn, make decisions, and act faster than your enemy—the same capability that allows startups to disrupt enterprises.23

Three men were especially important to the reconstruction of the Prussian Army following its defeat by Napoleon: Carl von Clausewitz, David Scharnhorst, and Helmuth von Moltke. Their contributions not only transformed the military doctrine; they have important implications for people leading and managing large organizations. This particularly applies to the idea of Auftragstaktik, or Mission Command, which we will explore here. Mission Command is what enables maneuver warfare to work at scale—it is key to understanding how enterprises can compete with startups.

Following the eventual defeat of Napoleon, General David Scharnhorst was made Chief of the newly established Prussian General Staff. He put together a reform commission which conducted a postmortem and began to transform the Prussian Army. Scharnhorst noted that Napoleon’s officers had the authority to make decisions as the situation on the ground changed, without waiting for approval through the chain of command. This allowed them to adapt rapidly to changing circumstances.

Scharnhorst wanted to develop a similar capability in a systematic way. He realized this required the training of a independent, intelligent cadre of staff officers who shared similar values and would be able to act decisively and autonomously in the heat of battle. Thus military schools were set up to train staff officers, who for the first time were accepted from all social backgrounds based on merit.

In 1857, Helmuth von Moltke, perhaps best known for his saying “no plan survives contact with the enemy,” was appointed Chief of the General Staff of the Prussian Army. His key innovation, building on the military culture established by Scharnhorst, was to treat military strategy as a series of options which were to be explored extensively by officers in advance of the battle. In 1869 he issued a directive titled “Guidance for Large Unit Commanders” which sets out how to lead a large organization under conditions of uncertainty.

In this document, von Moltke notes that “in war, circumstances change very rapidly, and it is rare indeed for directions which cover a long period of time in a lot of detail to be fully carried out.” He thus recommends “not commanding more than is strictly necessary, nor planning beyond the circumstances you can foresee.” Instead, he has this advice: “The higher the level of command, the shorter and more general the orders should be. The next level down should add whatever further specification it feels to be necessary, and the details of execution are left to verbal instructions or perhaps a word of command. This ensures that everyone retains freedom of movement and decision within the bounds of their authority…The rule to follow is that an order should contain all, but also only, what subordinates cannot determine for themselves to achieve a particular purpose.”

Crucially, orders always include a passage which describes their intent, communicating the purpose of the orders. This allows subordinates to make good decisions in the face of emerging opportunities or obstacles which prevent them from following the original orders exactly. Von Moltke notes that “there are numerous situations in which an officer must act on his own judgment. For an officer to wait for orders at times when none can be given would be quite absurd. But as a rule, it is when he acts in line with the will of his superior that he can most effectively play his part in the whole scheme of things.”

These ideas form the core of the doctrine of Auftragstaktik, or Mission Command, which, in combination with the creation of a professionally trained cadre of staff officers who understood how to apply the doctrine operationally, was adopted by multiple elite military units, including the US Marine Corps as well as (more recently) NATO.

The history of the Prussian Army’s development of Auftragstaktik is described in more detail in Stephen Bungay’s treatise on business strategy, The Art of Action (from which the above quotations from “Guidance for Large Unit Commanders” are taken).24 Bungay develops a theory of directing strategy at scale which builds on the work of Scharnhorst, von Moltke, and another Prussian general, Carl von Clausewitz. As a 26-year old, Clausewitz had fought against Napoleon in the fateful battles of Jena and Auerstadt. He subsequently served on Scharnhorst’s reform commission and bequeathed us his unfinished magnum opus, On War. In this work he introduces the concept of the “fog of war”—the fundamental uncertainty we face as actors in a large and rapidly changing environment, with necessarily incomplete knowledge of the state of the system as a whole. He also introduces the idea of friction which prevents reality from behaving in an ideal way. Friction exhibits itself in the form of incomplete information, unanticipated side effects, human factors such as mistakes and misunderstandings, and the accumulation of unexpected events.

FRICTION AND COMPLEX ADAPTIVE SYSTEMS

Clausewitz’ concept of friction is an excellent metaphor to understand the behavior of complex adaptive systems such as an enterprise (or indeed any human organization). The defining characteristic of a complex adaptive system is that its behavior at a global level cannot be understood through Taylor’s reductionist approach of analyzing its component parts. Rather, many properties and behavior patterns of complex adaptive systems “emerge” from interactions between events and components at multiple levels within the system. In the case of open systems (such as enterprises), we also have to consider interactions with the environment, including the actions of customers and competitors, as well as wider social and technological changes.25 Friction is ultimately a consequence of the human condition—the fact that organizations are composed of people with independent wills and limited information. Thus friction cannot be overcome.

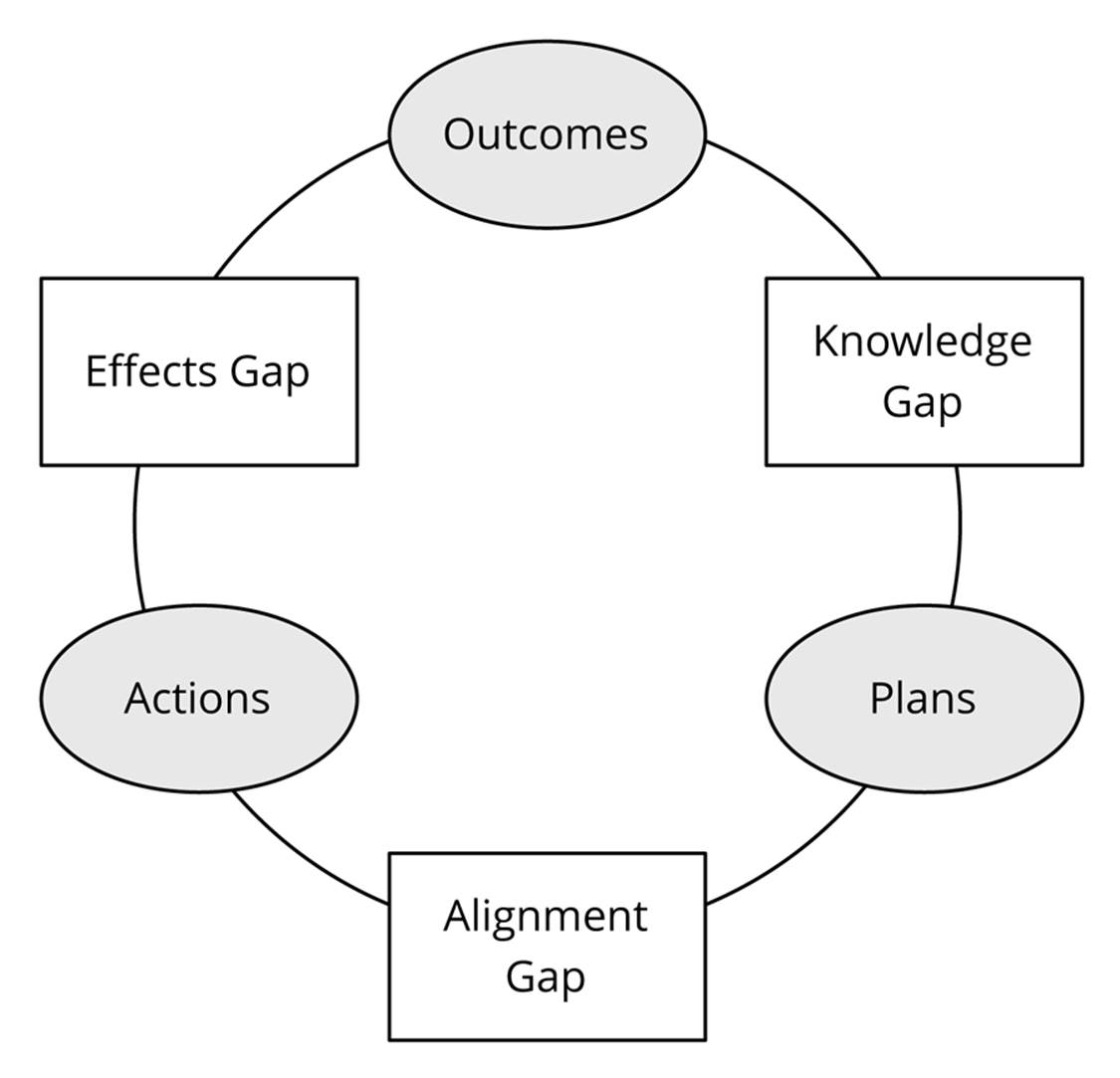

Bungay argues that friction creates three gaps. First, a knowledge gap arises when we engage in planning or acting due to the necessarily imperfect state of the information we have to hand, and our need to making assumptions and interpret that information. Second, an alignment gap is the result of people failing to do things as planned, perhaps due to conflicting priorities, misunderstandings, or simply someone forgetting or ignoring some element of the plan. Finally, there is an effects gap due to unpredictable changes in the environment, perhaps caused by other actors, or unexpected side effects producing outcomes that differ from those we anticipated. These gaps are shown in Figure 1-1.

Figure 1-1. Gaps in complex adaptive systems, from The Art of Action: How Leaders Close the Gaps between Plans, Actions, and Results by Stephen Bungay (reprinted by permission of Nicholas Brealey Publishing)

Bungay then goes on to describe the usual scientific management remedy applied by enterprises, the alternative proposed by the doctrine of Auftragstaktik, and his own interpretation of Mission Command as applied to business, which he terms “directed opportunism.” These are shown inTable 1-2.

|

Effects gap |

Knowledge gap |

Alignment gap |

|

|

What is it? |

The difference between what we expect our actions to achieve and what they actually achieve |

The difference between what we would like to know and what we actually know |

The difference between what we want people to do and what they actually do |

|

Scientific management remedy |

More detailed controls |

More detailed information |

More detailed instructions |

|

Auftragstaktik remedy |

“Everyone retains freedom of decision and action within bounds” |

“Do not command more than is necessary or plan beyond the circumstances you can foresee” |

“Communicate to every unit as much of the higher intent as is necessary to achieve the purpose” |

|

Directed opportunism remedy |

Give individuals freedom to adjust their actions in line with intent |

Limit direction to defining and communicating the intent |

Allow each level to define how they will achieve the intent of the next level up, and “backbrief” |

|

Table 1-2. The three gaps, and how to manage them |

|||

It is crucial to understand that when we work in a complex adaptive system where friction dominates, the scientific management remedies cannot work. In fact, they make things worse. Creating ever more detailed plans delays the feedback that would tells us which of our assumptions are invalid. Complex sets of rules and controls punish the innocent but can be evaded by the guilty, all the while destroying morale, innovation, and entrepreneurialism. Intelligence gathering fails in the face of bureaucratic or pathological organizations which hide or distort information in order to protect their turf. Organizations unable to escape the grip of scientific management are perfect targets to be disrupted by organizations that understand how to move fast at scale.

Create Alignment at Scale Following the Principle of Mission

The most important concern leaders and managers operating within a complex adaptive system face is this: how can we enable people within the organization to make good decisions—to act in the best interests of the organization—given that they can never have sufficient information and context to understand the full consequences of their decisions, and given that events often overtake our plans?

In The Principles of Product Development Flow,26 Donald Reinertsen presents the Principle of Mission, based on the doctrine of Mission Command, in which we “specify the end state, its purpose, and the minimum possible constraints.” According to the Principle of Mission, we create alignment not by making a detailed plan of how we achieve our objective but by describing the intent of our mission and communicating why we are undertaking it.

The key to the Principle of Mission is to create alignment and enable autonomy by setting out clear, high-level target conditions with an agreed time frame—which gets smaller under conditions of greater uncertainty—and then leaving the details of how to achieve the conditions to teams. This approach can even be applied to multiple levels of hierarchy, with each level reducing the scope while providing more context. In the course of the book, this principle is applied in multiple contexts:

Budgeting and financial management

Instead of a traditional budgeting process which requires all spending for the next year to be planned and locked down based on detailed projections and business plans, we set out high-level objectives across multiple perspectives such as people, organization, operations, market, and finance that are reviewed regularly. This kind of exercise can be used at multiple levels, with resources allocated dynamically when needed and the indicators reviewed on a regular basis.

Program management

Instead of creating detailed, upfront plans on the work to be done and then breaking that work down into tiny little bits distributed to individual teams, we specify at the program level only the measurable objectives for each iteration. The teams then work out how to achieve those objectives, including collaborating with other teams and continuously integrating and testing their work to ensure they will meet the program-level objectives.

Process improvement

Working to continuously improve processes is a key element of the TPS and a powerful tool to transform organizations. In Chapter 6 we present the Improvement Kata in which we work in iterations, specifying target objectives for processes and providing the people who operate the processes the time and resources to run experiments they need to meet the target objectives for the next iteration.

Crucially, these mission-based processes must replace the command and control processes, not run alongside them. This requires people to behave and act in different ways and to learn new skills. It also requires a cultural change within the organization, as we discuss in Chapter 11. Discussing how to apply Mission Command in business, Stephen Bungay reflects on a culture that enables Mission Command—which, not coincidentally, has the same characteristics that we find in the generative organizations described by Westrum in Table 1-1:

The unchanging core is a holistic approach which affects recruiting, training, planning, and control processes, but also the culture and values of an organization. Mission Command embraces a conception of leadership which unsentimentally places human beings at its center. It crucially depends on factors which do not appear on the balance sheet of an organization: the willingness of people to accept responsibility; the readiness of their superiors to back up their decisions; the tolerance of mistakes made in good faith. Designed for an external environment which is unpredictable and hostile, it builds on an internal environment which is predictable and supportive. At its heart is a network of trust binding people together up, down, and across a hierarchy. Achieving and maintaining that requires constant work.27

Your People Are Your Competitive Advantage

The story of the Fremont Assembly site doesn’t stop with NUMMI. It is in fact the locus of two paradigm shifts in the US auto manufacturing industry. In 2010, the NUMMI plant was purchased by Tesla Motors and became the Tesla Factory. Tesla uses continuous methods to innovate faster than Toyota, discarding the concept of model years in favor of more frequent updates and in many cases enabling owners of older cars to download new firmware to gain access to new features. Tesla has also championed transparency of information, announcing it will not enforce its patents.In doing so, it echoes a story from Toyota’s origins when it used to build automatic looms. Upon hearing that the plans for one of the looms had been stolen, Kiichiro Toyoda is said to have remarked:

Certainly the thieves may be able to follow the design plans and produce a loom. But we are modifying and improving our looms every day. So by the time the thieves have produced a loom from the plans they stole, we will have already advanced well beyond that point. And because they do not have the expertise gained from the failures it took to produce the original, they will waste a great deal more time than us as they move to improve their loom. We need not be concerned about what happened. We need only continue as always, making our improvements.28

The long-term value of an enterprise is not captured by the value of its products and intellectual property but rather by its ability to continuously increase the value it provides to customers—and to create new customers—through innovation.

A key premise of this book—supported by the experience of companies such as Tesla, among many, many others—is that the flexibility provided by software can, when correctly leveraged, accelerate the innovation cycle. Software can provide your enterprise with a competitive advantage by enabling you to search for new opportunities and execute validated opportunities faster than the competition. The good news is that these capabilities are within the reach of all enterprises, not just tech giants. The data from the 2014 State of Devops Report shows that 20% of organizations with more than 10,000 employees fall into the high-performing group—a smaller percentage than smaller companies, but still significant.

Many people working in enterprises believe that there is some essential difference between them and tech giants such as Google, Amazon, or Netflix that are held up as examples of technology “done right.” We often hear, “that won’t work here.” That may be right, but people often look in the wrong places for the obstacles that prevent them from improving. Skeptics often treat size, regulation, perceived complexity, legacy technology, or some other special characteristic of the domain in which they operate as a barrier to change. The purpose of this chapter is to show that while these obstacles are indeed challenges, the most serious barrier is to be found in organizational culture, leadership, and strategy.

Many organizations try to take shortcuts to higher performance by starting innovation labs, acquiring startups, adopting methodologies, or reorganizing. But such efforts are neither necessary nor sufficient. They can only succeed if combined with efforts to create a generative culture and strategy across the whole organization, including suppliers—and if this is achieved, there will be no need to resort to such shortcuts.

The second chapter of this book describes the principles that enable organizations to succeed in the long term by balancing their portfolio of products. In particular, we distinguish two independent types of activity in the product development lifecycle: exploring new ideas to gather data and eliminate those that will not see rapid uptake by users, and exploiting those that we have validated against the market. Part II of the book discusses how to run the explore domain, with Part III covering the exploit domain. Finally, Part IV of the book shows how to transform your organization focusing on culture, financial management, governance, risk, and compliance.

13 The story of the NUMMI plant is covered comprehensively in This American Life, episode 403: http://www.thisamericanlife.org/radio-archives/episode/403/, from which all the direct quotes are taken.

14 Behavioral scientists often classify work into two types: routine tasks where there is a single correct result that can be achieved by following a rule are known as algorithmic, and those that require creativity and trial-and-error are called heuristic.

15 Decades of studies have repeatedly demonstrated these results. For an excellent summary, see [pink].

16 Indeed one of W. Edwards Deming’s “Fourteen Points For The Transformation Of Management” is “Remove barriers that rob people in management and in engineering of their right to pride of workmanship. This means, inter alia, abolishment of the annual or merit rating and of management by objective” [deming], p. 24.

17 John Kotter, author of Leading Change, says, “a majority of employees, perhaps 75 percent of management overall and virtually all of the top executives, need to believe that considerable change is absolutely essential” [kotter], p. 51.

18 [westrum-2014]

19 [forsgren]

20 The survey measured organizational performance by asking respondents to rate their organization’s relative performance in terms of achieving its profitability, market share, and productivity goals. This is a standard scale that has been validated multiple times in prior research. See[widener].

21 In the interests of full disclosure, Jez was part of the team behind the 2014 State of DevOps Report.

22 This method of measuring attitudes quantitatively is known as a Likert scale.

23 As we discuss in Chapter 3, this concept is formalized in John Boyd’s OODA (observe-orient-decide-act) loop, which in turn inspired Eric Ries’ build-measure-learn loop.

24 [bungay]