REBUILDING CAPABILITY IN HEALTHCARE (2015)

5. Commencing the Journey

Most organizations tend to follow a similar early path on the Lean Sigma journey, starting with a low-resource, low-commitment “testing of the waters.” Typically this takes the form of one or two interested operations leaders identifying an individual or small handful of resources to attend a locally offered training, either at another nearby healthcare organization, through their third-party provider, or through a local academic institution. The selected individuals attempt a project on a very part-time basis and achieve reasonable, but limited, success.

The activity can remain in this state almost indefinitely if no further investment of effort is made on the part of leadership. Small, local-level project success will aid the sponsoring leaders, but no breakthrough in organizational performance will ensue until the broader Executive Team recognizes the value and is willing to grow the initial endeavor into something more—a program of some sort.

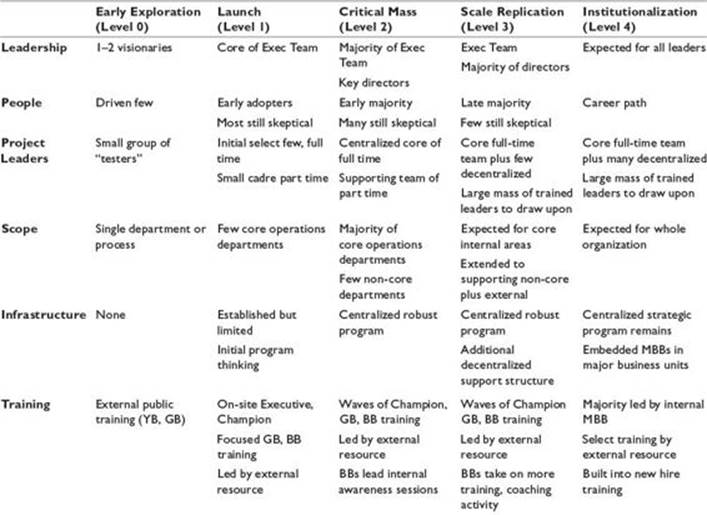

The stages of maturity, including this initial Level 0, are shown in Table 5.1.

Table 5.1 Stages of Lean Sigma Program Maturity in Healthcare

Many leaders mistakenly believe they are beyond this early exploration but wonder why they aren’t getting the real traction they are seeking, when in reality they may have some facets of a mature program in place but are missing some of the more basic program elements.

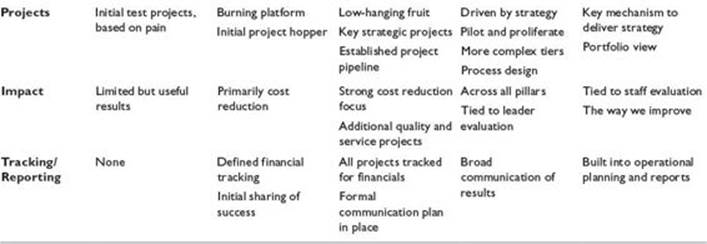

The key step here is deliberateness: taking time as an Executive Team to decide on the purpose and appropriate structure for a program—program design. All levels of an organization’s structure (executive, leadership, and management) need to be involved in order to build a successful change program, but this shouldn’t be done in an arbitrary fashion. Careful deployment design and execution are critical. Figure 5.1 shows a simple phased deployment approach. The approach is cyclical (for reasons to be explained later) and commences with the senior Executive Team.

Figure 5.1 Model for performance improvement deployment

I. Program Vision and Launch

Creating the foundation for a successful, integrated deployment begins with the Executive Team reaching consensus on what they want to achieve from the program and how they envision its structure—more specifically, to finalize and agree on the program concept, roles and responsibilities, timeline, resource selection and commitments, business case, and initial projects.

To achieve this, the key leadership and stakeholders are convened to define the collective vision for the program. To create this common vision, the Executive Team considers (in order) the following:

• What are the desired outcomes from the program (perhaps cultural, results, strategy execution, etc.)?

• What are the likely business problems to which the program will be applied? For example, growth, cost savings, quality, etc.

• What past/current initiatives have been undertaken? What were their successes and shortfalls? How will this program fit with those initiatives? For example, one particular program needed to connect directly with the organizational goal of performance excellence. Rather than create a new endeavor, the existing fragmented activity was unified, retasked, and realigned with the new approaches.

• How will the program fit with the current business model? Will it be centralized for the health system (say) or decentralized across it? Where will the accountability for program results lie?

• What are the preferred improvement methodologies (Lean, Six Sigma, other)? Are there any that must be avoided or downplayed?

• Who are the proposed Project Leaders? What are their time commitments, distribution, and depth of expertise? For one particular system it was decided that five leaders would be trained to a Black Belt level and float across three hospitals, tackling projects where they were most needed, rather than being dedicated to any one particular site.

• What is the likely scope of the deployment (operations, clinical processes, business, growth, supply chain, etc.)? For example, prior to a broader program being undertaken, one Executive Team chose to commence the program on a smaller scale in three of its system hospitals and to focus just on nursing. This allowed a more controlled beginning, a simpler initial focus of resources, demonstration of concept, and a learning environment for how this might work in the organization.

• Are there any preferred initial steps to move forward, such as process improvement or process standardization?

• What are the infrastructure requirements to support the program? What is the magnitude? Are they centralized or decentralized?

• What are the expectations for execution and delivering results? When should the program break even? How much return on investment (ROI) is being sought?

• What is the plan for internalization of mentoring and training skills?

• What are the constraints or barriers to being successful in the program?

• What is the ongoing role of any consulting partner(s)? For how long is consulting support needed?

Based on the answers to these questions, the Executive Team can agree on the program concept, roles and responsibilities, timeline, resource selection and commitments, and the business case and identify some initial projects.

II. Creating Program Infrastructure

Infrastructure is effectively the difference between just running a project here and there and having a fully functioning long-term program. Certain key elements need to be in place to ensure that the program has a robust foundation:

• An active Steering Group: To ensure ongoing focus and emphasize organizational commitment to the program, a Steering Group should be formed, meeting at least monthly to guide the program and ensure that key decisions are made and executed.

• Human resources engagement: The role of a number of individuals will change; therefore it will be necessary to involve HR to make active consideration of the associated organizational aspects. These include criteria for personnel selection, reward and recognition, career path planning, succession, and responsibility shifting and evaluation.

• Mechanisms to track projects and financial returns: To ensure that the program is successful in bringing value to the organization, it is important to ensure that financial returns are measured consistently using business rules, with specific guidelines on how and what to measure. In addition, the program may benefit from a project database that tracks the progress of individual projects as well as across the portfolio. This can range from a database software acquisition for a larger organization to a simple spreadsheet.

• An initial Communication Plan and package (reporting, messaging, and timing for the relevant audiences): In order to ensure the long-term viability of the program, acceptance by key leaders across the enterprise is important. A Communication Plan should ensure that stakeholders receive a consistent message, including how the program fits with corporate strategies and operations, roles, accountability, time frame, and goals.

• An inventory of potential projects, ready for implementation when the program is launched.

• Finalized project selection and draft Charters for the initial training wave of projects. A project needs to be simple enough for the novice leader to complete in reasonable time but bring significant business value to the organization.

• Finalized event selection and draft Charters for any initial quick-win Kaizen events.

III. Developing Organizational Competence

Changing a healthcare organization at the process level is very much about changing the people, both in behaviors and in performance, but also in competencies. To address persistent, stubborn business problems, proficiencies are necessary that are perhaps insufficiently available within the organization.

Competency development is usually thought to be synonymous with training, and as such training is often made the first priority without due consideration and planning. Unfortunately, classes are thus misaligned with the real competency development needs.

Building competency takes some thought to effectively and efficiently train the right people with the right skills. Following a plan of identifying needs and assessing current capabilities allows the Steering Group to develop just the talent needed, with a much greater level of success.

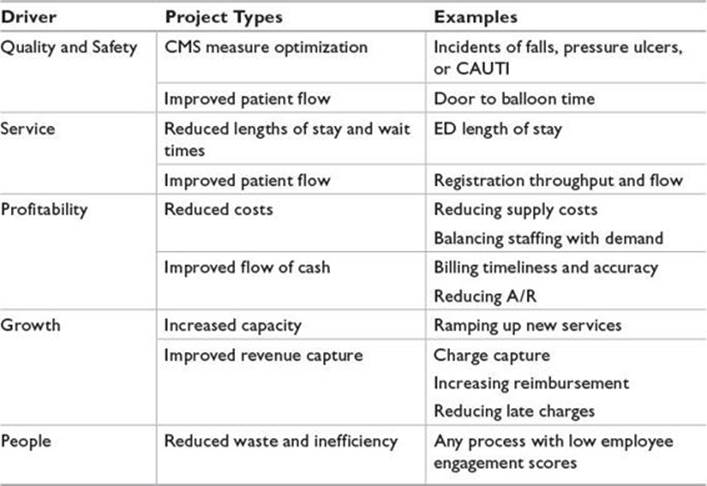

Figure 5.2 shows the basic flow underpinning competency development. As described previously, before jumping into training classes, earlier considerations need to be made. Within the adult training environment, classes need to deliver on the different skill sets, from executive-level awareness to the Project Leaders to the frontline staff. Exactly whom should we be training and on what? A little planning and thought are required. Thus, working backward in Figure 5.2 from the training itself:

• Before commencing training, the training structure and approach need to be defined and the materials generated to ensure that the classes will achieve the desired results.

• The classes are there to bridge a gap in knowledge, and so the gaps themselves must be understood. These are the major educational requirements for each role, that is, who needs to be taught what?

• To understand the gaps, the desired skills must be understood. What exactly do the trainees need to know?

• The desired skills are based on the methods we want them to employ and the roadmaps we want them to follow.

• The methods and roadmaps we want them to follow depend heavily on the roles we expect those individuals to play and within what defined organization structure. Are we looking to create a cadre of highly skilled change resources, crack commandos if you like, or an army of foot soldiers? The roles determine the skill levels required.

• The final step, working backward from training, is that the roles we want these individuals to play are based primarily on the business need we have at hand.

Figure 5.2 The flow of competency development

Thus, if we want to train the right people with the right skills in the most efficient and effective manner possible, we need to understand exactly what we are trying to achieve, what types of business problems we are trying to solve, and thus how best to structure our change resources.

In the vast majority of cases, organizations choose to build an internal capacity to deliver change, a cadre of autonomous change agents capable of applying the methodologies and tools to create value on an ongoing basis. These individuals may be that smaller, centralized corps of highly skilled specialists assigned to broader problem resolution, or they may be a larger, perhaps lower-skilled group dispersed throughout the organization to address local issues. These questions need to be asked early, with the understanding that the solution may be a mix of these.

It is important to school not only the change leaders in the right approaches, but also the recipients of change, along with other key stakeholders. Potentially the whole complement of staff may need to be engaged and given the appropriate skills and abilities to function as change is introduced, to realize the strongest impact and sustained results. Training needs, then, should be characterized as follows:

• To ensure that all projects in the program are successful, each project will have an internal Champion assigned to support the Project Leader (Black or Green Belt). The Champions will need to receive training outlining their various roles and interactions, and how they should be reviewing and supporting the projects, to ensure that barriers are identified and mitigated or removed.

• The Process Owner and recipients of change are trained and mentored to strengthen accountability and thus ensure sustained ongoing performance.

• The Steering Group is guided and mentored to finalize the infrastructure, identify and select the next project and Belt opportunities, ensure that the desired business value is achieved, and identify problems or issues and make course corrections if needed.

With respect to the training itself, classroom training is not the only vehicle for developing competencies. Each Project Leader is assigned a project to lead under the guidance of a seasoned project mentor, to ensure that they understand the right tools to use, in what order, along with the correct technical application. In addition, participation in projects facilitated by seasoned external resources, as a Team member or even as an observer, provides an opportunity to witness, close up, how the methodology and tools, learned in theory, are applied in practice. Both approaches accelerate the Belt’s ability to consistently bring project results autonomously and provide a dramatic difference in the return on investment.

E-learning is often a good supporting tool to create awareness of the program more broadly across the organization and is useful as a reference tool for practitioners once initial, more hands-on training is complete.

IV. Transforming Processes

Aside from the inherent advantage in delivering improvements, successful projects, especially in the early stages, bring visibility to the program, provide the training ground for Project Leaders, and provide the financial and cultural capital to fuel the program. This early concentration of effort provides an excellent opportunity to communicate proof of the program concept to the rest of the organization.

By pursuing projects meaningful to the organization, leaders learn the value the program provides to the organization, how it works, their role within it, the associated benefit, and the importance as a business change methodology. Projects may be identified, either driven by the strategic or annual operating plans or well recognized as “points of pain.” A full organizational assessment is usually not necessary for initial project selection, since leaders typically have insight into problem areas and processes that require prompt attention.

The Steering Group and Champions identify, prioritize, and sequence projects, balancing the need for projects to develop new Project Leaders with the business need for results; assigning some projects to leaders in training, others to existing change agents within the organization, and still others, when appropriate, to external resources.

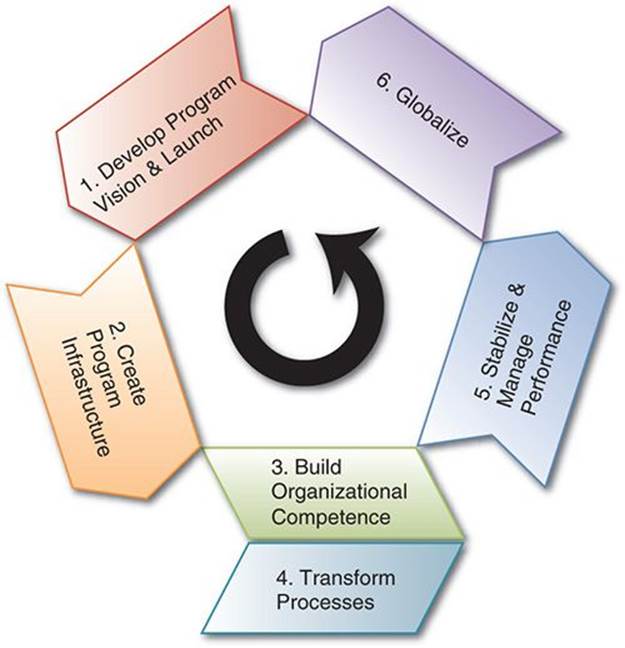

A spread of projects is key, in that it allows for the management of resources to not overburden one department or area but also brings some diversity in the types of returns gained. In the early stages especially, it’s important that the program not be perceived as singularly focused, as “just a quality thing” or “just a finance thing.” Some suggestions for considering these other types of returns are shown in Table 5.2.

Table 5.2 Example Projects by Driver and Type

The Steering Committee may also identify mission-critical or politically sensitive projects that cannot await internal training, or there may be complex interdepartmental projects that require prompt attention. In such cases, these projects that would be difficult for a novice internal change leader earlier in the deployment could be more appropriately led by skilled, experienced external resources.

To create support for the program and to gain some quick initial returns on investment, Kaizen events are often utilized. These events might provisionally target key finance processes such as billing with the goal of potentially funding the program for the charter year. The events are typically conducted in the first six to eight weeks of the program.

V. Stabilization and Performance Management

The most critical component of operational improvement is the Control Plan. Without that, even the best-intentioned improvements tend to drift back to the old way of doing things. Once improvements are made, process by process, robust Control Plans are put in place to ensure that performance is managed and sustained. As described in Chapter 3, the Control Plan for a process focuses on the decision making within and around the process to ensure clear accountability for responding to impending performance change, in a standardized way, and to mitigate problems appropriately.

In support of this control, the Process Owner and recipients of change receive training and mentoring in process standardization methods and performance management. Part of managing change is to know when to change and when not to change. Leaders learn not to overreact and instigate unneeded change. By resisting unwarranted change, the leader brings a calm to work processes and reduces the resource drain of persistent tweaking.

Leaders may opt to more rapidly bring about this process stabilization, rather than waiting for the application of change projects, by conducting sequences of multiple individual standardization events, as described in Chapter 3.1 Even though this isn’t a change approach, significant improvements in performance arise in more than half of processes.

1. Examples of such events as applied to registration and admission processes are described in Chapter 4.

In addition to performance management for processes, the overall program begins to settle into a rhythm in this phase. Ongoing Steering Group meetings continue to identify new opportunities, ensure that the business value is achieved (with reports to the executive on project and training status as well as returns), and to recognize and make needed course corrections. The future of the program depends on continuous oversight and the constant communication of successes.

VI. Globalization

A vast majority of programs commence with a focused start in one area of the business—a service line, perhaps, or within a few core functions. Clearly, benefits are achievable across the whole organization, so once the program is performing well and stabilized, it can be extended to other parts of the business. This in itself takes careful planning to avoid any misfires. Many programs run aground due to leaders underestimating the difficulties of extending to new areas. In most instances, it’s usually best to approach this with the same level of planning detail as the original focus.

Sometimes extension to new areas requires different approaches, such as new service development techniques or process design, which require some different management approaches and competences. As much as the DMAIC roadmap is a wonderfully flexible approach, it isn’t the one size that fits all.

Phase I Revisited

The cyclical nature of Figure 5.1 is an important aspect of these approaches. The initial vision and focus developed in the first cycle were based on a multitude of both internal and external factors, including, but not limited to,

• Relative market position

• Cost structure and financial performance

• Propensity for change

• Capacity of key processes

• Quality and service indicators, etc.

After many change projects have been conducted on what were key business problems, ideally many of these factors have been impacted and the landscape has changed. Just the simple fact that now the organization has more advanced capability for change can impact how the program is viewed.

It is extremely common for healthcare organizations to focus their Lean Sigma program on cost reduction in the first two years. This should be an extremely successful approach, but leaders quickly realize they can’t save their way to prosperity, and so a course adjustment is needed. Rather than do this in an arbitrary way, starting at the vision phase again pays dividends.

Second cycles can vary but often focus on growth, stabilization, or even extension beyond the realm of the initial organization—for example, moving from a single hospital to a system or perhaps extending to adjacent providers in the supply chain. In all of these cases it’s important to revisit the vision and ensure that the supporting infrastructure and competencies are in place.

How to Start

The hardest part of any journey is often taking the first step. My strongest advice, therefore, regarding starting is that you actually should start.2

2. In the words of Walt Disney, “The way to get started is to quit talking and begin doing.”

Now.

As mentioned earlier in this chapter, many organizations arguably have started the journey, or are in that Level 0, but stepping up to Level 1 requires energy to overcome the inertia. Leaders don’t typically drift into this; it requires a spark. Many leaders understand the value, but it still requires that catalyst.

A useful activity is to consider your organization’s readiness to deploy. Who is already “there”? Are there any key leverage leaders to make this happen?

It’s important to solicit support, but don’t hand this off. Ask key individuals to read this book, or parts of it that you think will resonate with them. Talk to, or better still visit, organizations that already have done well with Lean Sigma. If you don’t know any, take a look at the acknowledgments section of this book.

Above all, someone, wherever he or she is in the business, needs to drive this.

Why not you?

Why not now?