Tax Insight: For Tax Year 2014 and Beyond, 3rd ed. Edition (2015)

Part III. Investment Income and Deductions

Chapter 14. Retirement Investment Strategies-The Basics

Tax-Deductible and Tax-Deferred Retirement Plans

Contributing to a tax-deductible retirement account is a well-known way to reduce taxes. There are a multitude of deductible retirement account types, such as Traditional IRAs and 401(k), 457, and 403(b) accounts. Each of these account types has its own little twists in the rules that govern it, but the basic concepts behind each type of retirement account are the same. Each account type offers a deferral of taxes on any growth and a tax benefit for contributions. The government created these “tax qualified” savings vehicles to encourage people to save for their own retirement by giving them tax incentives for doing so. In this chapter you will learn how each of these retirement accounts works, what thorns you may encounter when using them, and when their use could actually turn to your detriment instead of your gain. You will also learn about how the new health care laws affect your retirement accounts, as well as a little known credit for retirement contributions that can bring amazing benefits to those who qualify for it.

Tax-Deductible Contributions

Most of the government-sponsored retirement plans offer an income tax deduction for contributing money to the plan. This means that the money that you contribute during the year is subtracted from your total income when calculating your Adjusted Gross Income (AGI), effectively reducing your taxable income and potentially allowing you to take more deductions and credits if your AGI is at or near some of the phase-out thresholds.

![]() Example Mary manages a dentist office. Her taxable income is $40,000, placing her in the 25% marginal tax bracket. If Mary contributes $5,000 to her IRA account this year, she will reduce her taxable income to $35,000, saving her $1,250 in federal taxes (25% × $5,000 = $1,250). Depending on the state she lives in, her contribution could reduce her state tax liability as well.

Example Mary manages a dentist office. Her taxable income is $40,000, placing her in the 25% marginal tax bracket. If Mary contributes $5,000 to her IRA account this year, she will reduce her taxable income to $35,000, saving her $1,250 in federal taxes (25% × $5,000 = $1,250). Depending on the state she lives in, her contribution could reduce her state tax liability as well.

The flipside of taking a deduction in the current year for contributions is that you will be taxed on that money in the future when you withdraw it. The prevailing notion is that you will benefit from doing this because your income needs in retirement should be less than your current income, so you will be taxed at a lesser rate in the future on those contributions.

![]() Example Sandi is 48 years old and is saving all that she can to prepare for her retirement in the future. She is currently in the 28% marginal income tax bracket. Each year she contributes the maximum amount that she is allowed to in the 401(k) plan offered through her work, which in 2014 is $17,500. By doing so Sandi reduces her current year’s taxes by $4,900 ($17,500 × 28% marginal tax rate = $4,900 fewer taxes paid).

Example Sandi is 48 years old and is saving all that she can to prepare for her retirement in the future. She is currently in the 28% marginal income tax bracket. Each year she contributes the maximum amount that she is allowed to in the 401(k) plan offered through her work, which in 2014 is $17,500. By doing so Sandi reduces her current year’s taxes by $4,900 ($17,500 × 28% marginal tax rate = $4,900 fewer taxes paid).

When Sandi retires in 20 years she intends to have her home mortgage paid off, her children established and financially independent, and many of her other current expenses taken care of. As such, she will need less income per year to cover her cost of living and estimates that she will be in the 15% marginal tax bracket during retirement. When Sandi withdraws money from her retirement accounts in the future she will pay only $2,625 in tax on a $17,500 withdrawal ($17,500 × 15% marginal tax rate = $2,625 in taxes). By taking a tax deduction for contributions during her working years, Sandi saved $2,275 in taxes on that income ($4,900 tax deduction – $2,625 eventual tax = $2,275 tax savings).

While you do receive an income tax deduction for contributions to a qualified plan, you do not receive a deduction for payroll taxes. You will still pay the employee portion of payroll taxes on your full income, regardless of whether you make a contribution (as well as the employer portion of those taxes if you are self-employed).

Tax-Deferred Growth

As discussed in Chapter 11, the tax code requires you to pay taxes on investment income realized during the year—even if you reinvested that income. Whether the income is from interest, dividends, or capital gains, the government wants its share of your earnings, and wants it now. Having to pay taxes on the growth each year can really cut into your overall investment earnings over time. If you didn’t have to pay taxes on the growth, you could instead put that money toward other investments and benefit from the additional compounding effect of the growth on those earnings.

The exception to this rule is when the investment income is held within a tax-qualified retirement account. In this case the government does not tax any growth within the account until you actually withdraw money from it. This allows the entire value of the account to grow untouched, freeing up other money to make additional investments (the money that would have gone to taxes).

Buyer Beware

Deductible retirement plans have their place, and in many instances they will reduce the total lifetime tax bill of an individual. However, there are many factors and assumptions at play in this analysis, and a change in one or more of those assumptions could actually cause you to be giving more money to the government in the end. Some of the potential outcome-changing issues are:

· Tax rates may not be the same in the future.

· You may need more income in retirement than you think.

· Required Minimum Distributions (RMDs) force taxation on these accounts.

· Withdrawals from retirement plans are taxed at ordinary rates, even the portion of the withdrawals that come from gains (and would have otherwise received favorable capital-gains tax treatment).

If the last three decades are any indication, it would be pretty safe to assume that there will be many tax law changes in the coming years and decades. These days it seems that the only constant feature in tax laws is change. Those changes can be beneficial, but they can also be harmful. If you are contributing money to a deductible retirement fund now and the tax rates increase significantly in the future you could wind up paying a lot more taxes in the end, and be doing so at a time in your life when you have little control over your net-of-tax income because you are no longer working. In the case of Sandi, in the previous example, if tax rates go up in during her retirement (instead of remaining steady as in the example) the projected tax savings from the contributions could be turned on their head and wind up being a significant increase instead.

In my experience with clients I have also found that many are surprised by how much income they need in retirement. They expect their costs to be reduced, but they don’t anticipate many things that keep their income requirements as high, or sometimes even higher, that when they were working. For some, all of the extra time on their hands leads them to spend more on projects, leisure activities, or hobbies. Others travel a lot more than they thought they would. A few begin to have significant increases in medical expenses. And others find that their children and grandchildren cost them as much as when they lived at home. Whatever the reason, if your income needs in retirement rival the income you required in your working years, your tax rates will not go down significantly, even if the tax laws remain the same—thwarting the tax-benefited calculations of retirement savings contributions.

Another factor affecting the true tax benefit of deductible retirement account contributions is that you must take Required Minimum Distributions (RMDs) from the account once you reach age 70½. If you have the ability to live on other income sources (pensions, part-time work, other savings, etc.), you could end up paying more taxes than otherwise necessary because of these RMDs. See Chapter 7 for a thorough discussion of RMDs and their tax consequences.

In addition to these factors, it can prove to be significant that retirement account distributions are taxed at ordinary income rates, even though a good portion of the value of the account may have come from capital gains. It may be more beneficial in the long run to pay capital-gains tax rates than to receive the tax deduction. The following scenario follows a likely pattern for many people, and illustrates the potential dangers of falling in line with the tax-deductible contribution bandwagon.

![]() Example Troy begins working for ACME Corp. at age 30 and immediately signs up to have $1,000 per year of his wages contributed to the company’s 401(k) plan. Troy never really thinks about the 401(k) very much again until he leaves the job 30 years later. At that time Troy withdraws the entire balance of the 401(k), pays taxes, and uses the net-of-tax amount to cover his cost of living while he seeks new employment.

Example Troy begins working for ACME Corp. at age 30 and immediately signs up to have $1,000 per year of his wages contributed to the company’s 401(k) plan. Troy never really thinks about the 401(k) very much again until he leaves the job 30 years later. At that time Troy withdraws the entire balance of the 401(k), pays taxes, and uses the net-of-tax amount to cover his cost of living while he seeks new employment.

During the first 15 years at the job Troy’s income increased steadily, but not significantly. In fact, during those years he never left the 15% tax bracket. However, during the second half of his tenure at the company his career began to take off as he climbed the corporate ladder, and his income climbed with it. In years 16–20 he was in the 25% tax bracket, then he moved to the 28% bracket in years 21–25, and finally he jumped to the 35% bracket in his final five years with the company. His 401(k) grew at an average annual rate of 7.2% over those 30 years.

When Troy withdrew the funds from his 401(k) the account value was $105,000 and after paying taxes at a rate of 35% he was left with $68,200 to live on.

If Troy had decided in the beginning to not use the 401(k), but instead take the net-of-tax income and invest it in a taxable account, he would have had more money in the end to use In the first year he could have taken the $1,000 of income instead of putting it in the 401(k), paid the 15% tax ($150), and invested the remaining $850. Then he could have continued that pattern for 30 years, investing the net-of-tax amount. In the end when he withdrew the funds he would have paid capital-gains taxes on the growth, instead of ordinary income tax on the entire balance as he did with the 401(k).

In this scenario he would have had an account balance of $85,600 and a net-of-tax withdrawal of $76,200 to live on. That is $8,000 more, net-of-tax, or a 12% increase. While $8,000 may not seem like much (because of the small dollar value being invested), a 12% difference is significant. If he had been investing $15,000 per year, instead of $1,000, the 12% difference would translate to $120,000 more in his pocket, after tax.

Incidentally, if he had increased his contributions (even doubled them) as his income increased (reflecting what some people do), he would still have come out with more money outside of the 401(k) than in it.

While I have greatly simplified several factors in this example, the point remains valid and clear: there are times and scenarios (perhaps many) where it would be more beneficial to invest outside of a tax-deductible qualified account than it would be to use one and receive the deduction. In this example the keys to the given result were an increasing tax rate over his working years, a continued high tax rate when he made withdrawals, and a low capital gains rate.

I have a friend who, as a CPA, often recommends that clients not invest in qualified accounts and put the money in tax-free bonds instead. The investment then earns tax-free income (just like the tax deferral of qualified accounts) and has no tax upon withdrawal of the funds (as long as the bonds are held to maturity). In addition, there are no other rules attached to the investment, such as being penalized for withdrawing funds early or forced to make RMDs later in life (and be taxed on them, of course), even if you don’t need them.

Do not misunderstand the point of this section. I am not saying that you should never consider making contributions to a qualified account. There are just as many scenarios where it could be more beneficial to do so. The point that I am making, though, is that it is not as straightforward as many people make it appear. Making contributions to a qualified account should be a carefully thought out decision, not one made as a tax-time, knee-jerk reaction to finding a way, anyway, to reduce the current year’s taxes. Just like making a spontaneous purchase on a credit card, you may end up paying a lot more for that decision in the end.

Types of Deductible Plans Available

There are many types of retirement plans that “qualify” for tax-deductible treatment by the IRS. All individuals are able to contribute to Individual Retirement Accounts (IRAs). In addition to IRAs there are numerous other retirement accounts that are sponsored by employers. Depending on the type of entity that employs you (government, for-profit business, non-profit, etc.), you may have access to one or more of these plans. Here is a list of some of the more common ones available:

· 401(k)

· 403(b) (Tax Sheltered Annuity)

· 457(b) (Thrift Savings Account)

· Simplified Employee Pension (SEP) IRA

· Savings Incentive Match Plan for Employees (SIMPLE) IRA

· Traditional IRA (not employer-sponsored)

At their core all of these plans function in basically the same manner. They are designed to allow an employee or business owner to contribute a portion of earnings toward saving for retirement and receive a tax deduction in the current year for that contribution. Each of these plans provides tax deferral on the growth in the account until the funds are withdrawn. And each of these accounts provides a means for the employer to make additional contributions into the employees’ accounts.

There is some variation in the rules between the different types of accounts when it comes to the amount an employee and employer are allowed to contribute to each year. The following sub-sections give some important individual details of the rules governing each type of account.

401(k), 403(b), and 457(b) Plans

401(k), 403(b), and 457(b) plans are almost identical in the rules that govern them, especially in regard to contributions allowed each year. The main difference is the type of employer (government, business, etc.). For the remainder of this subsection I refer only to 401(k) plans (to make it easier to read), but know that everything that I cover in this sub-section applies equally to 403(b) and 457(b) plans.

Each type of plan is set up by an employer and can receive contributions from both the employer and the employee. An employee may contribute up to 100% of his or her income, up to a maximum amount each year. The contributions are fully deductible for income tax purposes, but not deductible for payroll taxes.

The employer has the option of making three types of contributions. The first is a “matching” contribution, in which the business’s contribution is based on the employee’s contribution. For example, the match may be 50% of the employee’s contribution, up to $6,000. In this case, if the employee contributed $4,000 during the year the business would contribute an additional $2,000 to the employee’s account (50% match × $4,000 employee contribution = $2,000 employer match).

The second option for an employer is to automatically contribute a certain percentage of the employee’s income, often 2%–3%, regardless of whether the employee contributes. This method allows the employer to accurately project what the company’s contributions will be for the year, as well as ensure an equitable contribution for all employees.

The third optional contribution for employers who sponsor a 401(k) is making a “profit-sharing” contribution. This is just a contribution of a fixed dollar amount, not based on the employee’s contribution or salary. Contrary to its name, the business does not actually need to make a profit during the year in order to make a “profit-sharing” contribution.

Similarly to the rules for employees, the employer is subject to a maximum amount that it can contribute to an employee’s account during the year. The IRS sets a total contribution maximum for each year, which is the highest combined amount that may be contributed to an employee’s account between the employee and employer. So, the amount an employer may contribute is determined in part by what the employee contributed. For example, if the combined maximum is $50,000 and the employee contributes $15,000, then the employer may not contribute more than $35,000 to the account ($50,000 maximum allowed – $15,000 employee contribution = $35,000 allowed for the employer to contribute). In addition to this limit, the employer may not contribute more than 25% of the employee’s wages (or 20% of a self-employed individual’s gross income before the contribution).

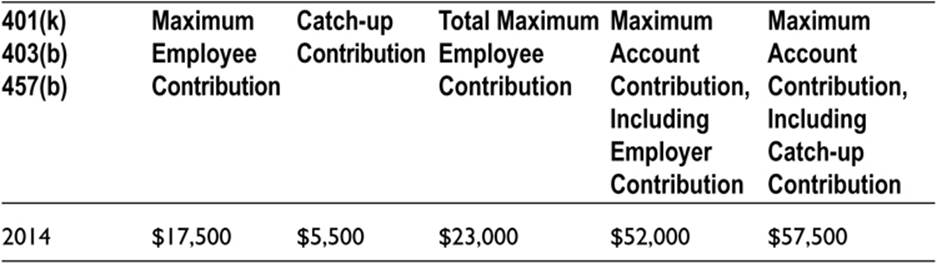

Individuals who are 50 years old (or older) by the end of the year are allowed to contribute an additional amount each year, over and above the “maximum.” This additional amount is known as a catch-up contribution and is meant to help those who are nearing retirement to put more money aside for that purpose. The catch-up amount allowed is adjusted each year for inflation and is also added to the total maximum amount that governs the employer contribution.

There are also rules governing a 401(k) plan that attempt to make the playing field equal between employers and employees by not allowing for discrimination between highly compensated employees and lower-paid individuals. These rules ensure that the plan is not limited to owners and executives in the business, as well as ensuring that profit-sharing and matching provisions are equitable. Any business owner contemplating the establishment of a 401(k) plan will need to be familiar with these rules and the financial implications that they bring. Many “safe harbor” provisions are available to ensure that the rules are followed, such as the automatic employer contributions mentioned previously.

401(k) plans give a business owner the opportunity to defer a significant amount of income each year. For example, a business owner who is 50 years old and makes $250,000 could contribute as much as $57,500 in 2014 to the plan, between employee and employer contributions (compared to a maximum contribution of $6,500 in a Traditional IRA). The business owner must take care to follow the non-discrimination rules if the business has employees, and the contributions to employee accounts must be weighed in the calculation of the overall tax benefits of the plan to the employer. Very often, though, the employer will be able to save enough money from the tax deferral of the plan that the savings far surpass the money spent on contributing to employee accounts. If the business owner has no employees (or a few low-wage employees, or employees who don’t save), the benefits can be even more significant.

There is also an option available to allow for Roth 401(k) contributions. It is up to the employer to decide if this option will be available in the business’s plan. Under this option the employee contributions that are designated as Roth contributions are not tax deductible, but rather taxable in the current year. However, the contributions and growth of these contributions are not taxed when they are properly withdrawn in retirement.

Only employee contributions can receive the Roth designation. Any employer matching or profit sharing must be made to the tax deductible, traditional 401(k) account. The plan must also maintain a separate account for the Roth contributions in order to keep a clear accounting of which assets are taxable and which are not.

For corporations (or businesses taxed like a corporation), the employer’s portion of the contribution must be made by the end of the year. However, for individual business owners (or businesses that are taxed like individuals), the contribution can be made as late as the filing deadline (including extensions) for the return. However, the plan must be in place before the end of the year. Table 14-1 shows the various limits of employer and employee contributions allowed during the year.

Table 14-1. Employer and Employee Contribution Limits for 401(k), 403(b), and 457(b) Plans

The regulatory requirements and non-discrimination testing that are required for 401(k) plans can be fairly expensive to comply with. For this reason many small employers have shied away from 401(k) plans and used other, less cumbersome plans instead. In recent years, however, a solution has been created in the tax code that makes 401(k) plans for business owners who have no employees much simpler to administer. These plans are sometimes referred to as a “Solo K” or “Single K” plan. If you have an employee, though, you will need to figure the cost of administration as a factor in weighing the benefits of a 401(k) versus some other plans, such as the SEP and SIMPLE IRA plans.

SEP IRA Plans

For business owners with no employees (as well as those with family-member employees), the most popular choice of retirement plans has been the SEP IRA. This is because of the minimal administration costs involved with the plan, coupled with high contribution limits.

SEP IRAs are contributed to solely by the employer. Contributions are based on a percentage of income and must be the same percentage for every eligible employee. Having to contribute the same percentage for employees as owners is a large factor in why these plans quickly lose their popularity among businesses with employees. If an employer would like to contribute 25% of his income to the plan, for example, he must also do that for each employee, which quickly eliminates the benefit that the employer gets from his own contribution.

The maximum total annual contribution for SEP IRAs is the same as it is for 401(k) plans, although it comes entirely from the employer side. The contribution can be up to 25% of an employee’s income, which is capped by an upper limit each year ($52,000 in 2014 or $57,500 for employees over 50 years old).

The calculation becomes more difficult for the owners of a sole-proprietorship. These individuals must calculate the net income of their business, and then subtract one half of the self-employment tax to arrive at “net self-employment income.” The business owner may then contribute any amount between 0% and 20% of net self-employment income.

An employer can set up a SEP IRA as late as the extended filing deadline for his or her return, as well as make contributions up to that date. This is more flexible than a 401(k), which must be set up before the end of the year.

While a SEP IRA is easier (and less expensive) to administer, a 401(k) will often allow a small business owner to contribute more money to the plan each year. This is because the 25%-of-income limit is placed on the entire contribution in a SEP IRA, while is only placed on the profit-sharing portion of the 401(k) contribution. If your income is not high enough to max out the total contribution limit, you may be able to combine the employee and employer contributions for a higher total amount.

![]() Example Zack is the sole proprietor of a small business and pays himself a W-2 salary. He has no employees and his total net business income is $150,000. The maximum contribution he would be allowed to make to a SEP IRA is $27,705 [($150,000 net income – $11,475 half of self-employment income = $138,525) × 20% max contribution = $27,705].

Example Zack is the sole proprietor of a small business and pays himself a W-2 salary. He has no employees and his total net business income is $150,000. The maximum contribution he would be allowed to make to a SEP IRA is $27,705 [($150,000 net income – $11,475 half of self-employment income = $138,525) × 20% max contribution = $27,705].

On the other hand, the maximum contribution that he could make to a 401(k) is much larger because he can contribute as both an employer and an employee. His total maximum contribution with a 401(k) would be $44,000 ($17,500 employee contribution + $26,500 = $44,000 total contribution).

The amount an employer contributes to a SEP IRA can vary year to year and, in practice, is often determined during the process of preparing the employer’s tax return. In this way also the SEP IRA is a very flexible plan for employers.

SIMPLE IRA

For the most part, the SIMPLE IRA lives up to its name. It is similar to a 401(k) plan in the sense that both the employer and the employee can contribute to it. However, the rules that govern the contributions, and the number of options available, are reduced. In addition, there is little to no administrative oversight needed for SIMPLE plans.

Employees may choose to contribute any amount, from $0 up to the maximum allowed for the year. The employer, on the other hand, is required to choose one of two contribution amounts and the election is applied across the board for all eligible employees. The business may either match employee contributions up to 3% of their wages or make contributions equal to 2% of employee wages, regardless of whether the employ makes a contribution.

![]() Example Sally’s Salon offers a SIMPLE IRA plan for its employees and matches their contributions up to 3% of the employee’s wages. One of the employees, Rachel, earns $40,000 per year and contributes $6,000 of her earnings to her SIMPLE IRA. Sally’s Salon must contribute an additional $1,200 to Rachel’s account to meet the 3% match requirement (3% × $40,000 wages = $1,200).

Example Sally’s Salon offers a SIMPLE IRA plan for its employees and matches their contributions up to 3% of the employee’s wages. One of the employees, Rachel, earns $40,000 per year and contributes $6,000 of her earnings to her SIMPLE IRA. Sally’s Salon must contribute an additional $1,200 to Rachel’s account to meet the 3% match requirement (3% × $40,000 wages = $1,200).

Mack’s Car Wash also offers a SIMPLE IRA to its employees. Mack, however, has chosen the automatic 2% of salary contribution. James works for Mack and does not contribute anything to his account. Even so, Mack must deposit the equivalent of 2% of James’ $30,000 salary to his account, or $600.

The maximum contributions allowed for a SIMPLE IRA are much lower than with the previous plans. In 2014, for example, an employee can contribute a maximum of only $12,000 (plus an additional $2,500 catch-up contribution for those who are 50 and older). The employer can contribute only the additional 2%–3% of the employee’s salary. Though the plan is very easy to administer, it is very limiting to those who would like to contribute the higher amounts that are available in other plans.

![]() Note Most of the retirement plans can be “rolled” into other plans. For example, on leaving an employer you can roll your 401(k) plan into a Traditional IRA to have more control over it and consolidate accounts. You could also roll it into another 401(k) plan with your new employer. This is not the case with a SIMPLE IRA, however. Funds from a SIMPLE IRA cannot be combined with the funds of a different type of account, nor can other accounts be rolled into it.

Note Most of the retirement plans can be “rolled” into other plans. For example, on leaving an employer you can roll your 401(k) plan into a Traditional IRA to have more control over it and consolidate accounts. You could also roll it into another 401(k) plan with your new employer. This is not the case with a SIMPLE IRA, however. Funds from a SIMPLE IRA cannot be combined with the funds of a different type of account, nor can other accounts be rolled into it.

Traditional IRA (Not Employer-Sponsored)

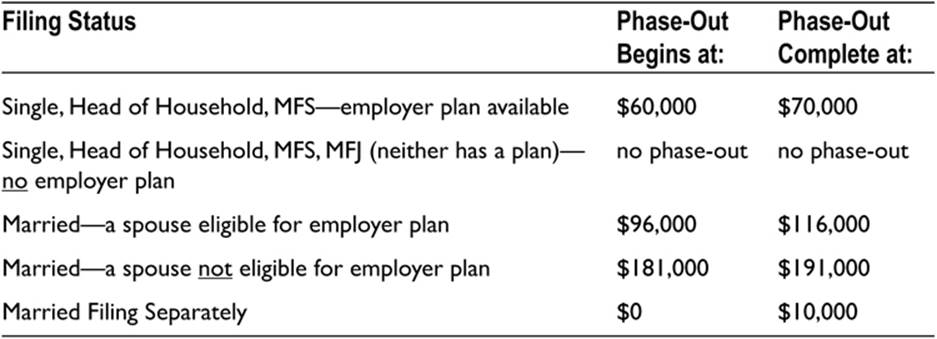

If you have no employer-sponsored plan at your disposal, you can opt for the Individual Retirement Account (IRA). A few people qualify to make a deductible contribution to both an employer-sponsored plan and an IRA, but only if their income is below the phase-out thresholds (seeTables 14-2a and 14-2b).

Table 14-2a. IRA Income Limits (Contribution Phase-Out Range) for 2014

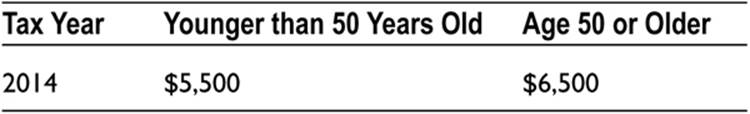

Table 14-2b. Maximum Allowable IRA Contributions

Each year limitations are set on the amount individuals can contribute to an IRA. For 2014 the IRA contribution limit is $5,500 ($6,500 if you’re 50 years or older). Unlike employer-sponsored plans, you can make the contribution any time up to the tax deadline for filing your return (usually April 15). You cannot extend this contribution deadline by filing an extension for your tax return.

![]() Caution To avoid penalties, contribute no more than the maximum amount to an IRA. The penalty is 6% of the amount of excess contribution for each year the excess contribution goes uncorrected. The good news is that if you accidently contribute more than you are allowed, you have until April 15th to remove the excess, penalty-free.

Caution To avoid penalties, contribute no more than the maximum amount to an IRA. The penalty is 6% of the amount of excess contribution for each year the excess contribution goes uncorrected. The good news is that if you accidently contribute more than you are allowed, you have until April 15th to remove the excess, penalty-free.

Your contributions to an IRA may not be greater than the total amount of your earned income for the year. For example, if you have only $2,500 in earned income for the year, you may not contribute more than a total of $2,500 to qualified retirement accounts.

![]() Tip There is one exception to this rule. If your spouse does not work, but you have sufficient earned income to contribute to IRA accounts, you can contribute to your spouse’s account. For example, if the wife earned $30,000 during the year and her husband had no earned income, the wife could contribute the maximum amount both to her own account and to her husband’s account.

Tip There is one exception to this rule. If your spouse does not work, but you have sufficient earned income to contribute to IRA accounts, you can contribute to your spouse’s account. For example, if the wife earned $30,000 during the year and her husband had no earned income, the wife could contribute the maximum amount both to her own account and to her husband’s account.

If you have sufficient earned income to qualify for an IRA contribution, that contribution need not come from your income. For example, you could simply transfer money from a savings account to an IRA. Also, some parents and grandparents will contribute to a child’s IRA or Roth IRA as a gift, which allows the child to use his income toward other goals. Be aware, though, that the giver gets no tax deduction for such a contribution.

For the purposes of IRA contributions, alimony income qualifies a person to contribute to an IRA even though it is not considered earned income. So a former spouse who does not work, but receives alimony, can contribute to an IRA.

If you or your spouse has access to an employer-sponsored retirement plan, your ability to make a deductible contribution to an IRA may be limited or even eliminated. For example, in 2014 a single taxpayer’s IRA deductions are limited when his Modified AGI (MAGI) reaches $60,000. His ability to contribute to an IRA is completely eliminated at an MAGI of $70,000. Here is the formula for calculating MAGI.

+ Adjusted Gross Income (AGI)

+ Social Security Income or Rail Road Benefits not included in AGI

+ Deductions taken for contributing to a Traditional IRA

+ Deductions taken for student loan interest or tuition expenses

+ Foreign income you have excluded and deductions for foreign housing

+ Interest from series I and EE bonds previously excluded

+ Employer-paid adoption expenses

+ Deductions taken for domestic production activities

= Modified Adjusted Gross Income (MAGI)

For married taxpayers the phase-out limitations become a little more complicated. There are two possible scenarios. First, if both spouses have an employer-sponsored plan available, the phase-out begins when MAGI reaches $96,000 and is eliminated at $116,000, in 2014.

![]() Example Troy and Lily are married, and both are eligible to participate in an employer-sponsored plan. They have a combined MAGI of $85,000. Because their MAGI is below the phase-out threshold of $96,000, they can both contribute the maximum amount allowed for an IRA.

Example Troy and Lily are married, and both are eligible to participate in an employer-sponsored plan. They have a combined MAGI of $85,000. Because their MAGI is below the phase-out threshold of $96,000, they can both contribute the maximum amount allowed for an IRA.

Max and Kathleen are married, and both are eligible to participate in an employer-sponsored plan. They have a combined AGI of $185,000. Because their MAGI is above the maximum phase-out range of $116,000, neither of them can make a deductible contribution to an IRA.

The second scenario occurs when only one spouse has an employer plan available and the other does not. In this case the MAGI phase-out range changes again. The spouse who has a plan available is subject to the limits described previously. However, the spouse who has no plan available has a much higher eligibility threshold, which is from $181,000 to $191,000, in 2014.

![]() Example Mitch and Trisha are married. Trisha has an employer plan available to her, but Mitch doesn’t. They have a combined AGI of $150,000. Trisha could not contribute to an IRA because the couple’s MAGI is above $116,000 and Trisha has a plan available to her. However, Bob can contribute fully because he has no plan available to him and the couple’s cumulative MAGI is less than $181,000.

Example Mitch and Trisha are married. Trisha has an employer plan available to her, but Mitch doesn’t. They have a combined AGI of $150,000. Trisha could not contribute to an IRA because the couple’s MAGI is above $116,000 and Trisha has a plan available to her. However, Bob can contribute fully because he has no plan available to him and the couple’s cumulative MAGI is less than $181,000.

Anthony and Jenny are married. Jenny has an employer plan available to her, but Anthony doesn’t. They have a combined AGI of $200,000. Anthony cannot contribute to an IRA, even though he has no plan available to him, because the couple’s MAGI is above the $191,000 threshold.

![]() Caution Notice that the limitation rules apply if you are eligible to contribute to an employer-sponsored plan. It does not matter if you actually contributed.

Caution Notice that the limitation rules apply if you are eligible to contribute to an employer-sponsored plan. It does not matter if you actually contributed.

Even if you are above the MAGI limits that allow you to claim a deduction for an IRA contribution, you can make non-deductible contributions. Although you get no immediate tax benefit for making such a contribution, you do get the benefit of tax-deferred growth in the account, meaning any gains on the investments are untaxed until they are withdrawn. You also pay no taxes on the portion of your IRA withdrawals that represent non-deductible contributions. (If you have a non-deductible IRA, see Chapter 10 for additional tax strategies.)

Before making a non-deductible IRA contribution, first consider contributing to a Roth IRA. This is a better choice if you are eligible to make such a contribution, since you get the benefit of not only tax deferral but also future withdrawals that will be 100% tax-free (assuming you follow all applicable rules).

![]() Caution Keep impeccable records of your non-deductible contributions, IRA withdrawals, and tax returns forever (not the usual seven years), because you may need to substantiate your non-taxable portion of the IRA.

Caution Keep impeccable records of your non-deductible contributions, IRA withdrawals, and tax returns forever (not the usual seven years), because you may need to substantiate your non-taxable portion of the IRA.

Penalties for Early Withdrawals

I once prepared a return for a client who had taken several thousand dollars from her retirement account, subjecting her to a 10% penalty on all of the money she had removed—in addition to the income tax she owed on the withdrawal. There was, however, a silver lining to the story, which I discovered as I worked on her return. She had spent a significant amount of money that year on medical bills (which are one of the exceptions allowed for penalty-free withdrawals) and, because of that, she was able to avoid most of the penalty.

The government does not want you to take money out of your qualified retirement accounts before you reach retirement age (i.e., 59½). If the government did not prevent you from removing funds from your retirement account, you would be able to manipulate your tax return by claiming deductions for contributions in a high-tax year and then withdrawing those contributions in a lower-tax year. For this reason, a 10% penalty tax is imposed for withdrawing money early from a qualified account.

![]() Caution In the case of the SIMPLE IRA, the 10% early-withdrawal penalty is actually increased to 25% if the money is moved out of the plan in the first two years.

Caution In the case of the SIMPLE IRA, the 10% early-withdrawal penalty is actually increased to 25% if the money is moved out of the plan in the first two years.

![]() Note 457(b) plans are the only type of qualified retirement account that does not have a 10% penalty for early withdrawals.

Note 457(b) plans are the only type of qualified retirement account that does not have a 10% penalty for early withdrawals.

The tax code does provide opportunities to make penalty-free withdrawals in certain circumstances. These exceptions available for employer-sponsored retirement plans are:

· Withdrawals that are rolled into another retirement plan within 60 days (this may only be done once per year)

· Distributions upon the death or permanent disability of the account owner

· Distributions upon separation of employment if the account owner is 55 years old (or older)

· Distributions to a spouse by a court order in a divorce

· Distributions up to the amount of deductible medical expenses during the year (whether or not deductions are itemized on the return)

· Distributions due to an IRS levy (at least they don’t penalize you when they take your retirement money)

· Distributions made as substantially equal periodic payments over the expected lifetime of the owner

![]() Caution The exception that allows for “substantially equal” withdrawals of the owner’s expected lifetime can be very tricky to orchestrate and carries significant financial risk. If you plan to withdraw funds under this rule be sure to hire a very competent professional to help you.

Caution The exception that allows for “substantially equal” withdrawals of the owner’s expected lifetime can be very tricky to orchestrate and carries significant financial risk. If you plan to withdraw funds under this rule be sure to hire a very competent professional to help you.

For non-employer–sponsored, Traditional IRA accounts, all of the exceptions above apply, except the one regarding separation from service after age 55. In addition to those on the list, there are a few other times when you can remove money from a Traditional IRA without incurring the penalty. They include:

· Insurance premiums for unemployed individuals

· First-time home buyer’s expenses. (The exception is for withdrawals up to a maximum of $10,000, and only once in an individual’s lifetime. It is also worth noting that a “first-time” home buyer is one who has not owned a home in the previous two years—not necessarily limited to the truly first-time buyer.)

· Education expenses (discussed more in Chapter 13)

![]() Tip If you need to withdraw money from an employer plan, such as a 401(k), but do not qualify for the exceptions, you may still have another option. If you are no longer working for the employer who sponsors the plan you can first roll the money into an IRA and then withdraw the money under one of the IRA penalty exceptions.

Tip If you need to withdraw money from an employer plan, such as a 401(k), but do not qualify for the exceptions, you may still have another option. If you are no longer working for the employer who sponsors the plan you can first roll the money into an IRA and then withdraw the money under one of the IRA penalty exceptions.

If you are still employed with the company, check with the Human Resources department to see if the retirement plan allows for loans to be taken from the funds. Many plans do allow for loans, which gives you the opportunity to withdraw funds without incurring taxes or penalties.

![]() Tip To qualify as a first-time home buyer, you can purchase the home for yourself, your spouse, your children, your grandchildren, or a living ancestor of you or your spouse. The “first-time” status is based on the purchaser, not the resident or owner.

Tip To qualify as a first-time home buyer, you can purchase the home for yourself, your spouse, your children, your grandchildren, or a living ancestor of you or your spouse. The “first-time” status is based on the purchaser, not the resident or owner.

![]() Tip The first-time home buyer exception is for a principal residence. So you could own a rental property and not own a principal residence, and you would still qualify for the exception when you buy a new home.

Tip The first-time home buyer exception is for a principal residence. So you could own a rental property and not own a principal residence, and you would still qualify for the exception when you buy a new home.

When withdrawing money from a retirement account, be sure to withhold enough taxes from the withdrawal to cover your additional tax liability at the end of the year, in order to avoid penalties and interest that are imposed on late payments of taxes. Also, if you take an early distribution, be sure to pay for all your medical bills and other “exceptions” before the year’s end to ensure that you utilize as much of the exemption as possible.

A More Subtle Penalty

While it is not a penalty per se, the Affordable Care Act (aka ObamaCare) could essentially penalize withdrawals from qualified retirement accounts by increasing taxes on other income. Withdrawals from IRAs will increase gross income, possibly triggering the 3.8% tax that is levied on income over the Modified AGI (MAGI) threshold of $200,000 for single individuals and $250,000 for married individuals. This tax is discussed in greater detail in Chapter 11, but it is worth noting its effects if you plan to withdraw money from tax-qualified retirement accounts.

Retirement Savings Contribution Credit

The tax code offers an added incentive for low-income earners to save money for retirement, in addition to incentives I’ve discussed previously. If your AGI is within the acceptable thresholds, you will not only receive the normal deductions for retirement contributions, but you’ll also be eligible for a special tax credit that is meant to sweeten the deal. This credit in and of itself is a “double-dip” opportunity.

If you have a 2014 AGI of less than $30,000 if you’re single, or $60,000 if you’re married, the credit offers an incentive to save at least $2,000 in a qualified retirement plan ($4,000 for married couples). The contribution can be to an IRA, a Roth IRA, or an employer-sponsored plan—including a 401(k), 403(b), SEP plan, SIMPLE, or 457(b).

![]() Tip Take note that one of the ways to become eligible for the credit is to contribute to a Roth IRA. You get a significant tax credit when you contribute to the account, and then you get tax-free growth and withdrawals in the future. This is an amazing opportunity to never be taxed on the money, and even be given more money (in the form of a tax credit) for making the contribution.

Tip Take note that one of the ways to become eligible for the credit is to contribute to a Roth IRA. You get a significant tax credit when you contribute to the account, and then you get tax-free growth and withdrawals in the future. This is an amazing opportunity to never be taxed on the money, and even be given more money (in the form of a tax credit) for making the contribution.

The Retirement Savings Contribution Credit is non-refundable, meaning it can reduce your tax liability to $0, but no less. You can take the credit against income taxes as well as the Alternative Minimum Tax (AMT), although if you qualify for the credit you wouldn’t be subject to the AMT as it currently stands.

The credit is calculated as 50% of the amount you contribute, up to a maximum credit of $2,000. So contributing more than $2,000 will not benefit you as far as the credit is concerned. The credit is phased out in steps, rather than evenly, which makes it important to use very careful planning. The maximum credit (50%) is available if your AGI is below $18,000 if you’re single, and below $36,000 if you’re married. If your AGI is above those numbers but below $19,500 or $39,000 (single or married, respectively), the credit is reduced to 20% of the contribution (instead of 50%). The credit steps down again, to 10% of contributions, when your AGI is above those thresholds. And the credit is no longer available once your AGI reaches $30,000 or $60,000 (single or married, respectively).

If your AGI falls within the parameters of this credit, you should recognize how significantly the credit increases the benefit of saving in a qualified retirement account. At times the credit will bring an even greater tax savings than the deduction.

![]() Example Dan and Emma are newlyweds who have just started a pet-grooming business together. Their AGI for the year is $30,000, and they each contributed $1,000 to an IRA, for a total of $2,000 between them. They receive an above-the-line deduction for that contribution, which saves them $300 in taxes. They also receive the retirement savings contribution credit, which saves them $1,000 in taxes! The deduction and credit combined bring a total tax savings of $1,300. In essence, they really contributed only $700 to their retirement accounts, and the government contributed $1,300. That is an instant 285% growth on the $700 net investment. That can’t be beat.

Example Dan and Emma are newlyweds who have just started a pet-grooming business together. Their AGI for the year is $30,000, and they each contributed $1,000 to an IRA, for a total of $2,000 between them. They receive an above-the-line deduction for that contribution, which saves them $300 in taxes. They also receive the retirement savings contribution credit, which saves them $1,000 in taxes! The deduction and credit combined bring a total tax savings of $1,300. In essence, they really contributed only $700 to their retirement accounts, and the government contributed $1,300. That is an instant 285% growth on the $700 net investment. That can’t be beat.

Remember the two components that determine the amount of the credit you receive. First, the credit is a percentage of the contribution. So the amount you contribute to a retirement account will affect the amount of the credit you receive. Second, your AGI will affect the percentage rate that is used for the credit—it can be 50%, 20%, or 10% of the contribution. Do not be dismayed, though, if your AGI makes it so that you receive only a 20% credit instead of a 50% credit. In this scenario you can still receive the maximum $1,000 credit by contributing $5,000 to your retirement accounts, instead of $2,000. The proportionate tax savings may not be as great, but a $1,000 tax credit on top of the deduction is still a significant savings.

![]() Caution If your AGI is on the borderline of the thresholds that determine whether the credit is for 50%, 20%, or 10% of your contribution, take special care in your planning. Just $1 of AGI over the threshold could reduce the credit from $1,000 to $400. In this scenario it would not be worth earning the first $600 of income over the AGI threshold, because you would be worse off financially for having earned it. If you are at the borderline of the AGI range, look for ways to limit your income or increase your above-the-line deductions so you can maximize the credit. For example, if your AGI were $100 over the 50% threshold mark, an additional $100 contribution to the retirement account could result in a $600 savings in taxes.

Caution If your AGI is on the borderline of the thresholds that determine whether the credit is for 50%, 20%, or 10% of your contribution, take special care in your planning. Just $1 of AGI over the threshold could reduce the credit from $1,000 to $400. In this scenario it would not be worth earning the first $600 of income over the AGI threshold, because you would be worse off financially for having earned it. If you are at the borderline of the AGI range, look for ways to limit your income or increase your above-the-line deductions so you can maximize the credit. For example, if your AGI were $100 over the 50% threshold mark, an additional $100 contribution to the retirement account could result in a $600 savings in taxes.

Because the tax code allows both a deduction and a credit for the same contribution, this is a double-dip opportunity. Based on the example of Dan and Emma (with their pet-grooming business) in the previous section, a tax savings of 65% was achieved for a person in the 15% tax bracket. This very significant savings makes this credit worth serious consideration for anyone in or near the qualifying AGI ranges. There are three additional things to be aware of when planning for this credit. First, you must be 18 years old or older by the end of the tax year to claim this credit. Second, before contributing to a retirement plan in order to receive this credit, be sure that you will have a tax liability. Because the AGI thresholds are so low for this credit, many who qualify for it owe no tax. Without tax liability, the credit affords no benefit, because it is non-refundable.

Third, the credit will not be so sweet if you withdraw money from a qualified retirement account two years before your contribution or one year after your contribution (up to the due date of the tax return, including extensions). If you make such a withdrawal, the amount of the contribution that qualifies for this credit must be reduced by the amount of the withdrawal or withdrawals.