Institutionalization of UX: A Step-by-Step Guide to a User Experience Practice, Second Edition (2014)

Part III. Organization

Chapter 12. Staffing

![]() The manager of the central user experience design group is the day-to-day leader of the central organization, and also manages the overall progress of user experience design in the company. It is better to have a good manager without much user-centered design experience than an expert who does not understand management.

The manager of the central user experience design group is the day-to-day leader of the central organization, and also manages the overall progress of user experience design in the company. It is better to have a good manager without much user-centered design experience than an expert who does not understand management.

![]() The central user experience design group needs UX professionals who play a number of types of roles. You may need to staff all of these roles and more:

The central user experience design group needs UX professionals who play a number of types of roles. You may need to staff all of these roles and more:

![]() Infrastructure manager

Infrastructure manager

![]() Mentor

Mentor

![]() Topical specialist

Topical specialist

![]() Ecosystem researcher

Ecosystem researcher

![]() The user experience design manager and practitioners do the actual user experience design work—they are generalists in user experience engineering and possess a solid skill set for the design process. In small companies, they may be a part of the central organization. In larger companies, they should generally report to the project teams within each line of business.

The user experience design manager and practitioners do the actual user experience design work—they are generalists in user experience engineering and possess a solid skill set for the design process. In small companies, they may be a part of the central organization. In larger companies, they should generally report to the project teams within each line of business.

![]() Using an offshore model is potentially a partial solution for almost any organization building its user experience design staff.

Using an offshore model is potentially a partial solution for almost any organization building its user experience design staff.

This chapter describes the staff roles needed for the institutionalization of user experience design and explains what to look for when hiring people to fill them. These roles do not necessarily map directly to job descriptions, as one person may fulfill a number of roles. Conversely, one role may be filled by several individuals. Mix and match them as necessary, but the roles must be staffed. In a very large organization, greater specialization is the norm, and it is more likely that several people will work on a given role. In smaller companies, a single individual often must handle multiple roles. For example, in a very small company with only one user experience engineer, that person may need to fulfill all the roles described in this chapter (a daunting requirement), while a medium-sized company might have a specialist in cross-cultural design who also has graphic art skills.

Earlier chapters discussed developing the infrastructure of the user experience design operation. As a result, you now have the knowledge necessary to create a “user experience design factory” complete with appropriate processes and tools. But the success of that factory very much depends on getting the right UX staff in place, and this is not an easy task. Only a limited number of educational institutions offer graduate programs for user experience design practitioners, and many graduates of these programs still need real-world experience.1 At the undergraduate level, there are some courses available in user-centered design but not degrees that focus on the necessary skills. Many countries are developing practitioner programs to meet this rising demand; thus an offshore model is another potential option for organizations to consider. In this chapter, I share insights gained during two decades of experience with hiring user experience design staff.

1. For a listing of the current university programs available, see www.humanfactors.com/downloads/degrees.asp.

The Chief User Experience Executive

Once the institutionalization effort has succeeded, a central user experience design organization should be in place (as discussed in Chapter 11). This organization reports to an executive, who may be a chief user experience officer (CXO), the senior vice president of marketing, or the head of quality assurance. Whatever the title or position, the set of activities and responsibilities this executive must fulfill requires no user experience design skill. Understanding the field is certainly important—but this job is really about large-scale organizational leadership.

It is a common mistake for organizations to put practitioners into this position. Teaching a practitioner to be an executive leader is asking a lot. Practitioners generally do not know how to direct a large-scale organization, setting the stage for things to go very badly. Highly skilled practitioners frequently think that to develop a user experience design practice, more smart people like themselves should be hired. Without leadership experience, they don’t understand the need to do large-scale, process-driven work.

In many ways, the user experience executive continues the role of the executive champion (refer to Chapter 1 for additional details on this role). It is essential to continue chanting the mantra of business focus for user experience design work and operating within the politics of the organization to ensure that support is obtained from key players. In some ways, these tasks are much easier to address now that the organization has been sensitized to user experience design issues and a foundation of support is in place. The initial strategy of institutionalization has given way to a far more complex set of projects and initiatives, and the executive must establish the balance among strategic activities, infrastructure, and tactical work. In addition, he or she needs to monitor progress, solve problems, and celebrate success.

During times of growth and prosperity, maintaining the user experience design team is not a problem. In contrast, during difficult times, the executive must make a solid case for continuation of the team. In the past, the usability organization was often cut early in a downturn—a development that can be discouraging for user experience design staff, and one that has prompted many talented people to leave the field. The executive needs to inspire a sense of purpose, commitment, and security in the organization. When a team is properly integrated and working in a mature way, then it will be sustainable through downturns and executive turnover.

No matter if you have just one UX practitioner or hundreds, you still need someone at an executive level playing the role of executive champion. The executive champion was critical in starting the process for institutionalizing user experience design, and a champion will be critical for continuing and maintaining user experience engineering practices. If you have a CXO, this person is most likely your executive champion. If you do not have a CXO, you need to clarify who your executive champion is.

The Central Usability Organization Manager

The executive champion or chief user experience executive provides high-level strategy and support. This role is essential, but the daily work falls under the supervision of the manager of the central user experience design organization, who has a very different job from that of the executives. The role of the central usability organization manager requires at least an understanding of user-centered design technology, along with very good connections in the organization. While the executive might spend a small part of his or her time on user experience design, the central UX organization manager is fully dedicated to the control and promotion of the user experience engineering capability within the organization. There is a rapidly growing set of skilled job candidates in this area, and an increasing body of knowledge about how to do that job well (see User Experience Management: Essential Skills for Leading Effective UX Teams, by Arnie Lund).

The central user experience design group has a whole agenda of projects and services for which the executive champion may provide overall direction, but the manager has to plan, fund, staff, and monitor each one. This job is a lot like running an internal consulting group—there is an infrastructure to maintain and a set of project offerings to design, create, market, and deliver.

The manager of the user experience design team is sure to spend a substantial amount of time addressing personnel issues—hiring good usability staff and cultivating them internally. Existing staff members also need to be mentored. Consequently, the manager should dedicate time to developing career planning and feedback sessions for this group.

The ideal qualities of a user experience design manager include in-depth knowledge of user experience engineering practices, a full grasp of the organizational dynamics, and a love of management. Such individuals have the expertise to chart the course for user-centered design work and contribute a great deal to the process. Owing to their in-depth understanding of organizational dynamics, even if they are not familiar with your organization, they will quickly familiarize themselves with it. The ideal manager is fully committed to user experience design and won’t get sidetracked easily.

If you cannot find or afford a “walk-on-water” user experience design expert with management skills, what should you do? You may be tempted to promote a highly skilled user experience design specialist who has a deep understanding of the field. After all, he or she will understand what needs to be accomplished, will be able to assess the quality of work, and can help make wise tradeoffs when difficult decisions arise. However, placing a practitioner without management experience into a leadership role might lead to the collapse of your institutionalization effort. Without a leader who has the necessary savvy and political skills, the entire user experience design organization may be marginalized and eventually eliminated. While some cultures can be supportive of a technical expert placed in a leadership position, the specialist is ill equipped to run with the wolves in most organizations—or even to run from them.

As a second choice, it is better to select a street-smart manager who cares about user-centered design issues, providing him or her with plenty of training and support. This person’s understanding of the management role and channels of communication is his or her most important capability, outweighing even limited user experience engineering expertise. The professional manager must be dedicated to user experience design and have the ability to build a team of experts—and then to grow that team and protect it. Ideally, the manager can mentor the team members in content as well as clear roadblocks for them. If he or she is not equipped to do so, the manager may need to delegate content mentoring to another staff person or an outside mentor.

The management role is the most critical for the team. If you have a manager who is not an expert, you will absolutely need one very key capability: someone who is able to select the methods that will be applied to each program and to estimate the scope of effort. This will take someone quite senior in the user experience design field.

It is often thought that the manager of the central usability team can also complete the work of the executive champion, but that misconception arises simply because many organizations do not appreciate the champion’s critical role. You need a true executive to be the executive champion. The role should not be combined with that of the central manager. Refer to Chapter 1 for details on the role of the executive champion.

The Central Usability Organization Staff

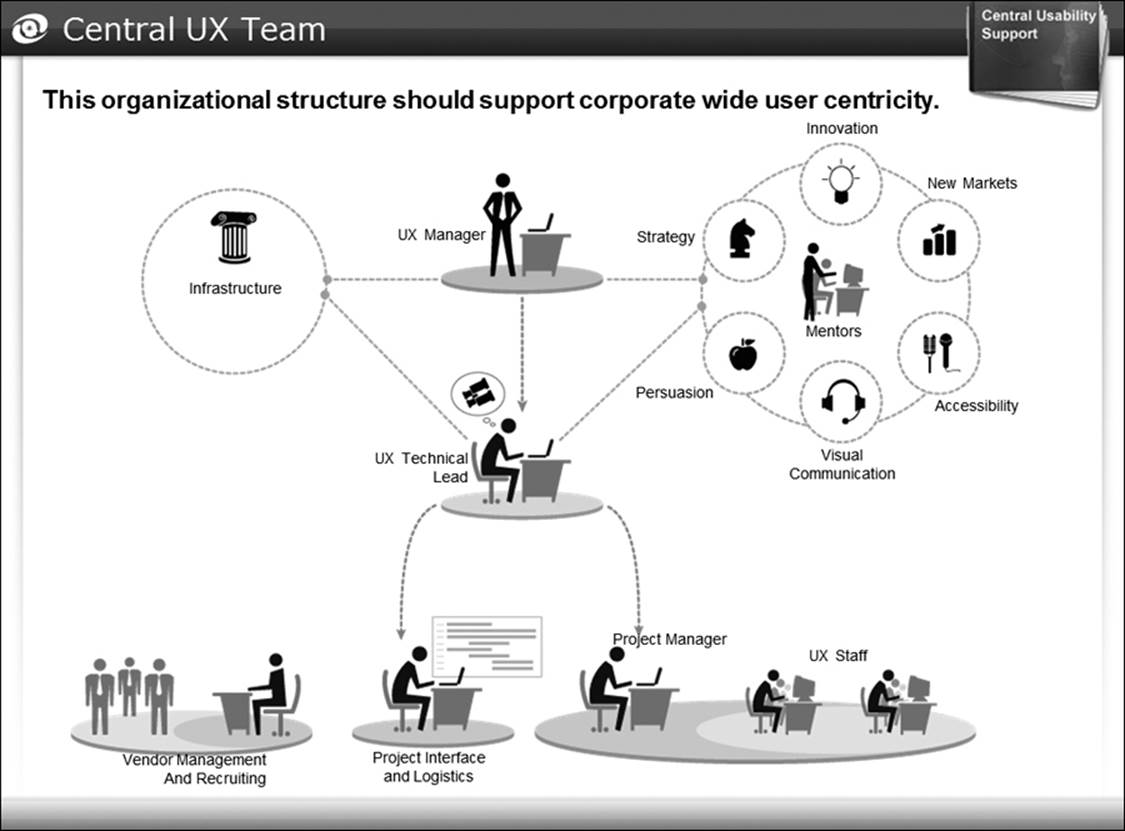

As mentioned in Chapter 11, the central user experience design group comprises a small nucleus of staff members with user experience design expertise who coordinate UX activities for the company (Figure 12-1). This central group forms the dissemination point for best practices and success stories. It must also manage challenges to maintain progress toward an optimized user experience. This group rarely includes more than 6–10 people. (In large organizations, additional staff members are distributed in project teams.) The central usability team is essential to keeping the institutionalization effort moving forward while remaining coordinated—and dynamic.

Figure 12-1: A large central group supporting project teams

We will define seven subroles that may be needed within this team to complete its centralized support functions: (1) infrastructure manager, (2) mentor, (3) topical specialist, (4) project planner, (5) project manager, (6) generalist, and (7) researcher. As with the concept of archetypes in mythology, there is usually a bit of each role in every user experience professional, although some people function well in only a limited set of areas, while others perform only one of these roles well.

The Infrastructure Manager

This role is far less proactive than that of the mentor, specialist, or generalist. The infrastructure manager spends much less time interacting with the constituent project teams. Instead, he or she is responsible for getting methods, standards, and tools in place—facilities that need to be maintained and disseminated as well. This has become an increasingly complex process. While the methods might not change much, the templates sitting alongside the methods will need to be refined and expanded.

There should always be a central facility to field questions about interface design standards and gather issues. A repeated request for an exception to a screen template, for example, could signal the need to add a new template. Tools all need to be administered and monitored. In addition, there is often internal training to provide.

The Mentor

People in the role of mentor reach out to guide and evaluate junior user experience design staff and provide selective support on many projects. Junior usability staff members have a lot to manage. They are often performing activities such as data gathering and testing for the first time, and they need support and encouragement while they build confidence in their abilities. It is hard to walk into a testing facility and face your first test participant—there is always a fear that you will not be able to manage the session. This fear is not unfounded. Some test participants repeatedly go off on tangents. Others harbor resentment about something the company did and want to talk about nothing but that one erroneous item on their bill. The consultant often accompanies junior usability staff members to a few sessions until their confidence increases.

Aside from emotional support, the mentor is there to provide an infusion of technical expertise when it is needed. Often, a few moments of attention from the consultant—noticing, for instance, that the task analysis documentation is too detailed—can help a junior professional avoid weeks of unnecessary work, averting real dangers to design quality. Seeing that the design concept requires impossible technology or could be accomplished with a simple, standard page type can also make future rework unnecessary. The mentor plays a key role in developing technical expertise through his or her guidance.

Fulfilling the requirements of this role can be great fun. A mentor gets to make a positive impact in many arenas, but rarely has to stay to complete what is sometimes considered difficult and uninteresting detail work. This role is the ideal job for the more aggressive and highly skilled usability generalist.

It is essential to have high-quality technical skills for this role. The mentor must be able to evaluate processes and designs without spending a great deal of time on analysis or reflection. He or she must be decisive and definite, and as the final authority in many UX issues, cannot afford to be wrong very often.

At the same time, mentors should be emissaries for the user experience design initiative, constantly educating the organization about the value of UX design and the resources available in the organization. Just like external consultants from a usability vendor’s organization, these internal consultants must create positive impressions and bonds.

The Topical Specialist

The need for a specialist role depends on the type of work the company does. There are many types of specialists in the user experience engineering field. Software user experience is a specialty within the overall field of applied psychology, which includes transportation, military equipment, consumer products, aviation, and other subfields. Numerous subspecialties exist within software experience engineering. If your organization’s core competency involves one of these subspecialties, it may make sense to hire a user experience design professional with expertise in this particular area. Following are some of the more common areas of specialization within the field of user-centered software engineering.

The Technology Specialist

Some user experience design specialists focus on particular types of software technology. These experts may specialize in mobile or Web applications, graphical user interfaces (GUIs), voice response systems (both touch tone and voice recognition), phones, and other handheld units. There is a lifetime’s worth of detail in each of these areas. For example, a good general practitioner or consultant knows the basics of a voice response script and knows how to make menus short and simple. Nevertheless, complex strategies come into play when tuning a voice recognition algorithm; even the way that the software determines the end of a word is challenging [Kotelly 2003]. If the core business of an organization involves voice recognition software, it is worthwhile to have staff specialists who understand these nuances. If there is only an occasional, specialized area of need, however, it is best to find a specialist to hire on a contract basis.

The User and Domain Specialists

Specialists focus on particular domains or user types. Some focus just on the design of software for children, on financial applications, or on the presentation of graphic models for oil drilling. Every domain has its own language, insights, and challenges. While it is true that a good consultant can make a positive impact on almost any application, there is real value in hiring someone who has experience in your particular domain. For example, if the company is wholly focused on building gaming software, it pays to have a specialist familiar with the gaming industry, environment, and customer populations.

The same developmental activities are needed. You cannot just go to the specialist and say, “You have been building gaming applications for 30 years, so make one for me.” This approach will at best result in duplicating the design, business strategy, unique selling proposition, and branding of a previous client. Instead, the specialist should go through a de novo, full, user-centered design process. This ensures the creation of a design that precisely fits your organization’s competitive strategy. The specialist’s expertise helps save time in understanding the domain and improves the quality of questions, thereby enabling your organization to avoid pitfalls. He or she will likely be able to accommodate design requirements that may not be obvious. Nevertheless, the full user experience design process is needed to create a competitive design.

The Developmental Activity Specialist

A good general practitioner or consultant in the field can complete the full range of developmental activities in the user experience design methodology. However, some professionals specialize in a limited part of the development life cycle, such as conducting usability testing. Developmental activity specialists are often less expensive to hire than generalists because their skill set is limited. These specialists may be very useful as members of project teams, or they may be collected in a service organization within the central usability group—which deploys the group’s specialty more cost-effectively. You can apply their work across many projects throughout your organization.

Some specialists work on very sophisticated parts of the user experience design methodology. Developing an appropriate UX strategy is both critical and difficult. It requires someone who understands how to extract ideas from executives, who is familiar with business models, and who can envision large scale, cross-channel designs.

Other practitioners specialize in innovation. Everyone tries to be innovative in what they do, and you can certainly be trained to be more innovative—but serious innovation programs are entirely another matter. These programs are large-scale efforts that understand a business space and generate many ideas about new offerings and business models that are then systematically envisioned and evaluated.

Finally, specialists are commonly employed to run controlled experiments. If you need a scientifically valid comparison between designs with appropriate statistical treatment, you will need someone who has a solid experimental design capability—a characteristic that is somewhat uncommon among user experience design generalists.

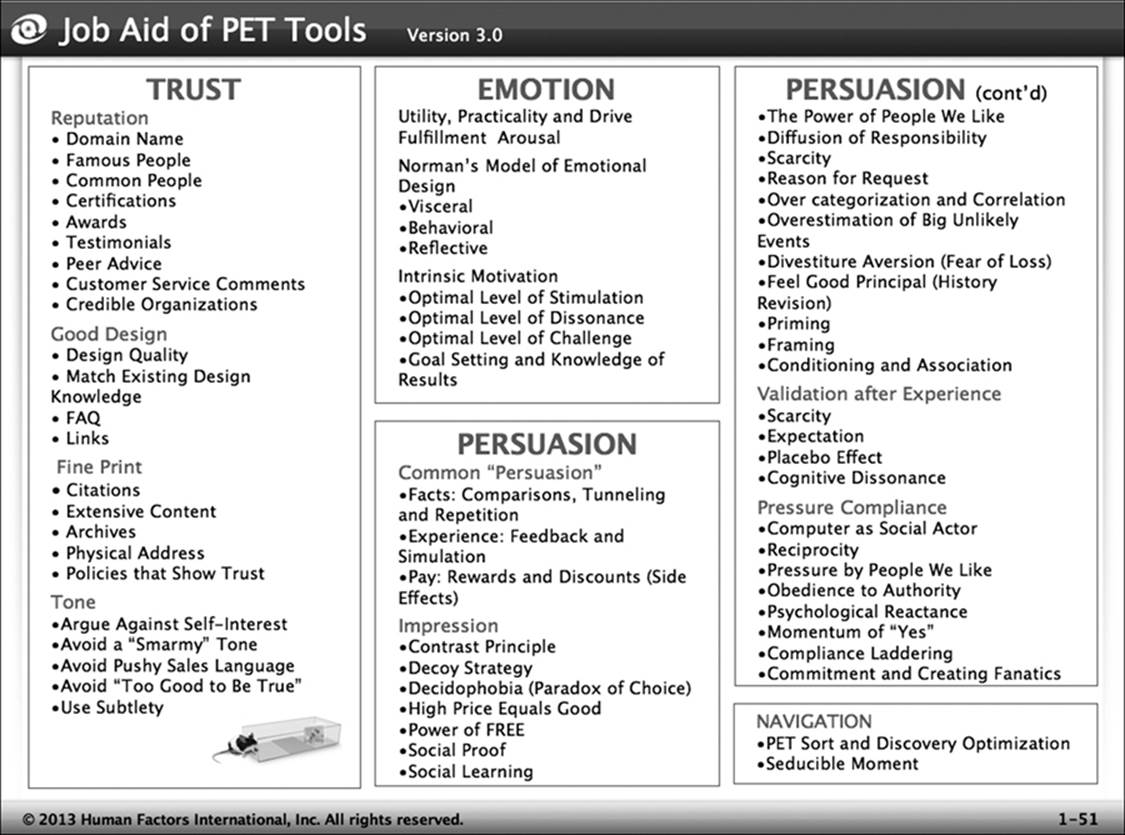

The Persuasion Engineer

The rationale of making a design that is easy to use is essentially accepted everywhere. It is the “table stakes” of design—if you intend to be in business, your digital channels should be usable or you should not even try to be in the game. Today, however, the arena of competition is going well beyond simple ease-of-use. Don Norman [2002], one of the great thinkers in the usability field, has described how design must go beyond usability. We are now in a struggle to make interfaces that are enjoyable and compelling. It turns out that there is a whole set of research-based models, skills, and methods specific to emotional design. From UX strategy, through innovation and user-centered design, there are special activities that your persuasion engineering expert needs to complete to ensure a compelling solution. The design might need impressive graphics (we will cover that shortly), but being compelling is not at all synonymous with graphic richness. Consider two of the most persuasive interfaces online: those of Amazon.com and Facebook: though not graphically rich, they are quite compelling for more fundamental and powerful reasons.

The persuasion engineer is responsible for using a whole set of methods that shape emotion and trigger conversion (Figure 12-2). Of course, graphics can be part of the solution. Just consider two highly successful applications: slot machines and World of Warcraft.

Figure 12-2: Persuasion engineering tools from HFI’s basic course on persuasion, emotion, and trust (PET design)

The Cross-Cultural Specialist

Cross-cultural experts have a really in-depth understanding of how to adapt an application to different cultural contexts. All trained user experience design consultants are sensitive to the issues of globalization and localization of software and are aware of the challenges within this area. For example, a well-trained consultant for an American company would never approve the name “Morning Mist” for a perfume product destined for sales in Germany, a country where mist means manure.

A cross-cultural specialist will understand which principles of design make translation easier, such as “Do not embed variables in a sentence that will be translated because syntax changes will shift the order of the variables, making the rendering of translated sentences hard to code and maintain.” Consider the following English text: “Thanks, [username]! That is [units bought] [color] [product] added to your account.” In Spanish, it would translate correctly as follows: “Gracias, [username]! Eso es [units bought] [product] [color] agregado a su cuenta.” Thus the programmer would need to reverse the sequence of color and product.

The generalist can do a credible job of avoiding many pitfalls in cross-cultural design. However, specialists in the field spend their professional lives seeking to understand the issues and processes of localization and have models that identify key differences between cultures that may impact the design. They know the characteristics of the target culture that will be of special concern.

If your business is defined by having a certain expertise, you will benefit from having at least one of these numerous types of user experience design specialists on board. The Social Security Administration, for example, will have accessibility experts. Large multinational organizations will have experts in emerging markets. A deep R&D operation will have theoretical cognitive scientists. A game company might have a positive psychologist (who studies fun and happiness).

Besides the specialists listed here, specialists may focus on areas such as multidimensional data, visualization methods, online search strategies, security, and font design. While it is important not to expect a specialist to be able to play a more generalist role within the usability team, if your organization is working within a very specialized domain, it may make sense to have a specialist on board.

The Ecosystem Researcher

As computers become more ubiquitous, we must consider a far more complex context for our designs. We can no longer just look at a person using an application. Instead, we have to consider many people playing different roles—that is, complex social and physical environments. So many of these contextual issues come into play that some businesses have started using cultural anthropologists and ethnographers to enhance their understanding. These researchers see things differently from classic applied psychologists. They look at the roles of various actors in a given setting. They are sensitive to the context, communication, values, and rules in a given setting. Their job is to study a given ecosystem, model the ecosystem, and then guide development of facilities that will effectively operate within that context. For many organizations, a central team—staffed with the right specialists—can perform this research and then share the results among many different design teams.

The UX Manager and Practitioners

In small organizations, the central group lends usability specialists to projects. In medium-sized and large organizations, practitioners work for lines of business and are assigned to specific projects. The project team may have only a single user experience design person, yet two different roles must actually be provided: a management role and a working practitioner’s role. The manager is really the project manager for the user experience design activity. Fulfilling this role means creating a plan for user experience design work within the project. The company methodology lays out a generic project plan, but it is up to the manager to mold that plan and designate the specific activities and resources to make the generic methodology fit the project’s time frame, budget, and key objectives. This takes a great deal of creativity and experience. It requires a top-level staff person with advanced degrees, certifications, and a proven track record. This person must address many issues and business decisions.

HFI has seen that an experienced project team manager with good planning skills can cut as much as 10–15% from the time and effort of the usability work. A poor planning job, in contrast, may make a usability project fail. Project planning is not composed of a single activity, but rather must be refined and revisited throughout the process. Project planning for usability work is mostly about finding shortcuts and avoiding traps, and the project team manager is instrumental in making such outcomes happen. The following list gives a sense of the level of planning considerations required:

• The current application is obviously bad, and everyone knows it. The manager decides to skip an initial usability test on the current application and go right to the design phase. This shortcut saves $60,000 and three weeks of time.

• The manager is told that users are hard to find but still does not agree to gather data from internal users. The internal staff, interviewed as surrogate users, would be biased by the company viewpoint, and several additional features might be mentioned that are of no interest to the real users. Avoiding this trap saves $250,000 in unneeded development and coding.

• During a project team discussion about the best width of the text, team members say they want to run a study to find the answer. The manager recalls seeing research, looks it up and makes a clear recommendation for a 100-character-wide display, thus putting an end to the discussion. This saves the team another two days of fighting and prevents an unnecessary study—a shortcut that saves three weeks and $30,000 to do the research.

• The team immediately wants to begin detailed page designs, coding them concurrently. The manager forces the team to make standard templates and reusable code. This cuts the final development time by three weeks and avoids customer complaints due to inconsistent, idiosyncratic designs—saving three weeks and $80,000. There are increased sales as well due to improvements in customer perceptions.

• The key business objective is to make the site self-evident. Rather than employing random or stratified sampling, the manager decides to just study low-end users. The team can test with just 20 users instead of 50, and still get better data. It’s a shortcut that saves four days of time and $15,000.

Between avoiding traps and finding shortcuts, a good project team manager uses his or her experience to save the company time and money.

In the absence of a strong central user experience design manager, however, the project team manager may have to build the team. This means recruiting and screening the right staff for the group, attending to the career development needs and personal motivations of team members, and mentoring and growing the staff.

Finally, on an ongoing basis, the manager must support the project’s progress. He or she must lead difficult negotiations with the other developers, track project milestones, unsnarl logistics, and allocate staff resources. Constant interactions with the other development team members are required, and adjustments in schedule must be made to accommodate them.

The project team manager role must be staffed by someone who understands the user experience engineering process well. Project planning is the toughest part of this role, but it is possible to get help for planning from the central user experience design team. Nevertheless, even if such assistance is provided for the management of the project plan, the execution of the plan requires someone who knows the details and vicissitudes of usability work. The person responsible for the usability of the project should complete the project planning. This is not the CXO, the executive champion, or even the usability team manager. This type of project management involves managing a specific project, not the user experience design group as a whole.

The Creative Director and the Graphic Designer

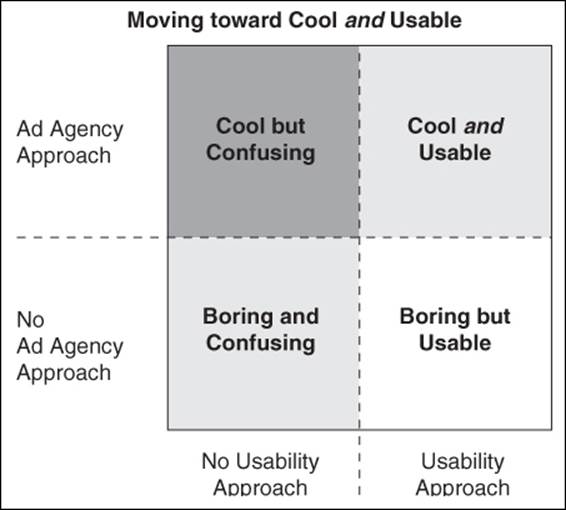

Traditionally, user experience engineers seek to make practical, useful, and usable designs. However, achieving these goals is often not enough. Designs must be satisfying, pleasant, inspiring, entertaining, and beautiful (Figure 12-3). This is the new frontier of the user experience design field. Unfortunately, today’s usability staff members are often ill equipped to reach the visual design aspect of this goal on their own. Instead, to satisfy this requirement, user experience design staff must work with graphic designers.

Figure 12-3: Dr. John Sorflaten’s matrix of usability and creativity

When the design must appeal to the user’s emotions, creative and artistic functional roles must be built into the project along with user experience design roles. Their degree of involvement and importance varies. If the site is an online brochure, the usability staff may have little to do, while the graphic design staff may need to do quite a bit of work on the creative design and presentation. Conversely, within a human resources site designed for an intranet, very little creative work may be required. For example, users of this site may want to see only their 401(k) account and benefits. While an appealing graphic skin on the site needs to be designed to support the company’s brand, expenditures on aesthetic work should be limited. In most projects, however, there is a balance of these two perspectives. Public sites and shrink-wrap applications are two examples of projects that need a wise balance between user experience engineering and creative design.

To make a site beautiful, you need to bring in skilled people. There must be functional roles for both the creative director and the graphic designer. These people come from visual arts and design backgrounds, and many have also joined the interactive design field from advertising backgrounds. The creative director generally develops the concepts for the design, while the graphic designer does the physical drawing as well as creates alternative designs to meet the objectives of the creative director, and is responsible for decisions such as regarding color palettes and font families.

Integration of the user experience design and creative design efforts is some times tricky. These groups have different perspectives and methods, and they may not agree on the design. In a worst-case scenario, both groups want to control the interface structure, standard templates, and final page designs.

When bringing together these two separate viewpoints, you need to manage the situation. Each side needs to become sensitive to what the other is trying to accomplish. It is imperative to negotiate clear boundaries and roles to make this collaboration succeed. The right solution depends on the type of application being designed. To see how this plays out, let’s examine in greater depth two of the examples mentioned earlier in this chapter.

If your organization is designing an online brochure, there is little need for complex interactivity; user speed and accuracy are also of less importance. In such a case, you can hire a creative director to run the project. The UX team can check the designs to make sure there are no obvious points of confusion and perhaps run a usability test to confirm that there are no places where the user gets lost or frustrated. Nevertheless, the focus of the project is really on its creative design.

Building a site for employees to set up benefit elections on the intranet poses a very different challenge, one that requires greater interaction. Users are not interested in being entertained by the site—they just want to get the job done quickly. In this case, let the user experience design team determine its process, and have a graphic artist complete a basic treatment of the design—there is little creative work to do.

You should also consider setting up an interdisciplinary team in which a user experience engineer, a graphic designer, and perhaps a technical writer work together as equals. The UX engineer will be responsible for navigation and interaction, the graphic designer for the graphical elements, and the technical writer for writing and editing content.

Outside Consultants

It may seem odd to hear this from a vendor, but the best practice in the UX design field is not to rely on vendors to solve your user experience design problems. Many companies have tried bringing in a bunch of brilliant consultants, with each creating a brilliant design. Everyone is impressed and applauds, and the vendors go home—but then the designs steadily become degraded over time. Most critically, the diverse vendors create a diverse set of misaligned solutions. While each solution might be lovely, collectively they don’t fit together as a whole. It is essential to have a strong internal group to avoid these pitfalls. This group might contract for some work, but it controls the strategy, processes, and standards.

Vendors are quite useful in helping to set up a mature practice (after all, you set up the practice only once). They can also be a source of staff working for the central group. And there is one unique role that can be filled only by a vendor: because the outside consultant is not a part of the organizational structure, he or she can act as impartial arbiter and facilitator. This type of consultant can offer a unique set of services, and his or her impartiality can help break logjams while “saving face” for the internal staff.

The outside consultant can also communicate at any level of the organization. Within an organization, strong protocols usually prevent a staff member from walking into the CEO’s office and raising difficult topics and concerns. The consultant, in contrast, is permitted and encouraged—and paid—to be critical. This type of service is an important part of the institutionalization solution.

What to Look for When Hiring

Hiring your first user experience design staff can be tricky. The market for UX personnel is poorly defined, and the people responsible for recruiting and hiring in your organization may not have experience or guidance in what to look for.

An organization hiring senior people for the first time may have a difficult time finding them. Senior practitioners in the user experience design field are still a small group, and they tend to be networked together through professional groups such as the ACM SIGCHI and the User Experience Professionals Association.2 In terms of more junior staff, there are thousands of people in the field (and many thousands more who claim to be).

2. For more information on ACM SIGCHI, visit www.acm.org/sigchi/. For more information on the Usability Professionals Association, visit www.upassoc.org.

The Social Security Administration’s Usability Team

Sean Wheeler, Lead Usability Specialist, Social Security Administration

We currently have 18 people on the Usability Center staff at the Social Security Administration (SSA). Half of the staff members have their master’s degrees, and one holds a Ph.D. More important than title, their training is consistent in areas directly related to usability. In addition to academic credentials, they typically brought 7 to 10 years of experience in usability when they joined our team.

We are a rather strange lot because our team is a well-integrated mixture of federal employees and contractors. Because the contractor staffing mechanism is available to us, the SSA Usability Center has team members with skills that would be impossible for us to obtain otherwise. As an example, we are able to do electronic prototyping within the Usability Center so we can get a reading on the accessibility of our designs early in the software development process—a high-value contribution to project teams within the federal government. Our federal staff members bring many years of experience as employees from SSA field offices with the corresponding knowledge of the laws and procedures of the agency, as well as the needs and expectations of our customers that comes only from direct public contact work. This combination of skills has served us very well.

We are really expanding our scope now. We’re a much different organization now than we were a few years ago. Today, most of our staff has been involved in user interface design and human factors work for 10 to 15 years, with much of that experience taking place in the private sector. The team’s skills allow us to support agency-wide process changes that put early focus on user needs and design rather than on the late-in-life-cycle usability testing we started with. This rapid infusion of skills allows us to support project teams in ways that would have been impossible when the center was established in 1996.

Most companies have a very limited number of user experience design experts on staff; many companies do not have one person with the entire user experience design skill set described here. In many cases, the bulk of the UX staff may have to come from outside hires, though this practice has its pitfalls. It is important for the user experience design team to be an integral part of the organization, so it helps to have team members come from within the organization. If most of the UX staff members are outsiders, it may be very hard for the team to be fully accepted. Insiders understand the organization better and may fit in better than new hires.

That said, collectively the pool of insiders from whom you are recruiting probably have very few user experience engineering skills. Consequently, these people will need a strong management commitment for their training, mentoring, and consultative support.

If your organization is new to user experience design, consider using recruiters who specialize in user experience design staff. They will be familiar with the best people in the field and will know when someone is ready to move. They can also help screen more junior staff. Your recruiter should have extensive technical expertise and testing methods to make sure you get the people who best meet your needs. Once you have a core of experts in your organization, you may be able to have them work their own networks and go to user experience engineering trade shows to track down potential new staff members.

Hiring user experience design staff is a big step that involves a huge investment in the form of salaries, benefits, management, facilities, and training. But these elements form only a small part of the risk. The far larger risk is in the opportunity cost for designs that are not competitive. A new employee will be at least in part responsible for the quality of the user experience and performance of many applications over time. If this staff member is a poor practitioner, these costs can easily dwarf his or her loaded labor rate. The necessary skills to look for and selection criteria you should employ, based on HFI’s many years of experience in hiring user experience design staff, are discussed in the following subsections.

Selecting and Training Skilled Professionals

As mentioned earlier in the book, user experience design work is not just common sense. If it were, you could simply tell your staff to pay attention, and the resulting designs would be successful. (Many executives have tried this with very limited success.) Without concrete user experience design skills, however, we consistently get designs that are suboptimal—or worse. To avoid this problem, you bring in professionals and train internal staff. But first let’s explore what to look for.

A core philosophy and feeling for design is perhaps the most important prerequisite for a good user experience design professional. Specifically, the practitioner’s philosophy should be user oriented. This doesn’t mean simply asking the customers what they want and giving it to them—that is a sign of an immature or ill-trained practitioner. Rather, you should hire someone who sees the user’s needs and psyche as something to understand, to design for, and to support.

The user experience design practitioner needs to focus on the practical viewpoint of the user and systematically bring technology to the user’s service. To test for this orientation, check out how specialists react to the idea of a cool new technology that is clearly impractical for users. They may be polite about it, but they should exhibit a feeling of disdain. User experience design practitioners should act as a protective shield against flashy ideas that don’t help people use your sites, applications, and software effectively and enjoyably. A bit of jaundiced skepticism goes a long way.

User experience design staff must understand human behavior and be able to predict how users will react to and operate sites, applications, and software. In a good training program, students read research articles and predict the results from the methodological description. They view designs and predict their success. In time, they should become adept at prediction, developing a sense for what will confuse users and which physical manipulations are awkward. They should understand what makes users uncomfortable or angry, and be able to predict the time it takes to complete an operation or learn a procedure. While these predictions may not be exact, when created by an experienced user experience practitioner they should be fairly accurate.

Many design decisions are based on the ability of the user experience design specialist to estimate user consequences quickly. To get a sense of this, it is beneficial to have prospective staff members review some page designs to determine whether users can quickly see the things that matter most. I have often used a terrible clothing site design for this purpose. The site is organized by brand; thus, while shopping, the user has to identify the brand and then see all the different types of clothes from that manufacturer. Good prospective employees immediately see that the user needs the site to be organized by male and female categories and then by types of clothes.

Potential candidates need to have a good overall knowledge of UX research and models within the field. Any good candidate should probably have a foundation of “top of mind” user experience design facts. He or she should immediately know, for instance, that about 7% of men and 0.4% of women have some color weakness [Goldberg et al. 1995], or that all displays can be seen as a competition between the signal the user should perceive and the surrounding noise [Rehder et al. 1995]—and that the work of a user experience designer is to maintain a signal-to-noise ratio that gets the message through.

User experience design practitioners should know that there are population stereotypes for how things work, and that they differ between user populations (e.g., pushing a light switch up in the United States to turn on the lights versus pushing the light switch down in the United Kingdom to do so). Practitioners should know that users see things in context and can make mistakes as a result. For example, if users expect to see a letter, a handwritten “13” can look like a “B.” Users also make common keying errors, such as hitting the letter “o” instead of the number “0.” Looking up each issue becomes tedious in practical circumstances. When he or she has a solid foundation in UX design, the practitioner already knows the answers to many common questions—as well as some that others may not think to ask.

Staff members also need to be able to find answers when they encounter things they do not know. It is not acceptable for a user experience design practitioner to simply make up recommendations out of thin air. There is a time to hunt for the right answer, and practitioners need to be willing to check the research. They also have to know how to use it. Research in the UX field is spread across more than a hundred different sources, so the practitioner needs online and print resources he or she knows well, and must know how to find other studies when required.

The good practitioner regularly reads the literature to learn from new research studies. Sometimes he or she needs to retrieve studies to determine the best design decision. Understanding research papers is not easy, however. Research can provide invaluable insights, but it must be evaluated with great care. The practitioner must understand enough about experimental design and statistics to be able to interpret the research correctly. Not every staff member needs to have this capability, of course—a practitioner can ask for help. Nevertheless, having the skill set readily available within your organization is quite useful.

It is important to be familiar with a methodology so that the design process can be approached systematically. Ask potential employees what they would do to ensure that a site is usable and persuasive. It is worrisome if they do not have a systematic methodology with clear activities and deliverables that build toward a solution. Any activity such as “We will listen to the users” is suspect. What comes out of that listening? How does it really help the design? If they cannot talk their way through a systematic approach, practitioners are unlikely to follow one—even if you hand them a copy of your methodology.

The development process requires a whole string of user experience engineering activities. The usability practitioner must know how to complete tasks like expert reviews, usability tests, in-depth interviews, task designs, wireframe designs, detailed designs, and functional specifications. Each of these tasks requires numerous subskills. For example, being able to “do” an interview includes the ability to stratify user segments, develop target user types, and develop a recruiting strategy—and that is just one small part of the overall process. It is worthwhile to inventory the applicant’s experience with these activities and ask some questions about his or her approach to specific tasks. However, because it is difficult to really get a good sense of the quality of an applicant’s work without direct experience, consider having potential employees work through a set of examples and evaluate the results of their work.

Being a user experience engineer is not easy. As outlined here, general practitioners need to know a lot, but beyond the core skills and knowledge, user experience engineers need to have a passion for crafting a customer’s experience. They need to have communications skills such as the ability to excel in team interaction, and a sense of charisma that they can draw on when evangelizing usability.

Education

Although some highly skilled and effective people have a less formal education in UX design, most user experience practitioners have at least a master’s degree in the field. Having a solid educational background is important. Many colleges and universities now offer usability programs. The Human Factors and Ergonomics Society (www.hfes.org) currently lists 72 graduate programs in the field in the United States, including all kinds of user experience design work. The professors in these programs may specialize in factory workspaces, consumer products, the biomechanics of heavy lifting, or military equipment, however, so you must check carefully to see which program actually provides appropriate skills for software design.

Senior usability people may have been in the field long enough to predate specific degree programs. Many of these people have master’s or doctoral degrees in psychology instead of human factors, usability, or user experience.

Of course, a master’s degree or higher does not indicate that the practitioner has a full set of skills. In fact, most programs typically cover basics such as general design principles or ways to read research. Some courses may provide experience in usability testing. Keep in mind, however, that education is truly only the beginning of the process of becoming an expert practitioner. Experience is a critical factor—and it cannot be learned in the classroom.

Another, perhaps more useful validation to consider is certification. Several certification programs exist. For example, the Board of Certification in Professional Ergonomics provides a very good certification with requirements for education, experience, and testing (there are three alternative certification types based on the certificant’s preference: CPE, CHFP, and CUXP). In addition, HFI’s certification program is currently used by approximately 10% of the world’s UX design professionals. In either case, the certification gives you quick assurance of proven expertise.

Experience

In looking at applicants’ experience, start with an assessment of the quality and range of their past work activities. There are obvious limitations to having worked on just a single application, particularly given that the applicant may have had a very limited role such as just running usability testing. Someone who has worked on a number of sites and applications has gained a wider perspective. Unless you are seeking someone with a limited and specific scope, look for a candidate who has completed many different user experience design activities. Once the new practitioner is on board, he or she can easily be drafted to work on the development team for a critical project. It is helpful if applicants have a wide spectrum of capabilities because—even though you may have hired them for a particular expertise such as usability testing—it is likely that they will be called upon to perform other tasks as well.

It is also worthwhile to consider the quality of the project experience. While it is not particularly important that an applicant has worked on “name-brand” projects, he or she should have worked on projects where user experience was valued and given a significant role. Some practitioners spend years in a reactive mode—they essentially sit in their offices and review designs, reacting to aspects of the design that are so obviously awful that they can be discerned without having to gather data or complete a user-centered process. These people do not have much experience in supporting a solid process and appropriate methodology.

While one can get a degree and read many books, maturity of skills within the user experience design field really requires explicit mentoring, so it is important to acquire staff members who have worked under a good mentor. Perhaps the least organized aspect of the industry, mentoring is critical nonetheless. A mentor can help a practitioner develop many different professional skills—team interaction, presentation style, and good writing, for example—as well as a fundamental design approach and the ability to perform specific user experience design tasks. If you are not familiar with specific mentors whom applicants have had, it can be difficult to determine whether the potential employees have been well taught. The best thing, if you have the resources to do it, is to set up your own mentoring program, either in-house or with an outside consultant.

A Background That Includes Design

User experience design work requires many analytical activities. The professional must be able to run studies, compile results, and make recommendations. There is research to be reviewed and assimilated, and valuable insights to be gained about user psychology and behavior. These activities, however, are very different from the synthesis necessary for actual design. It is common to find skilled analysts who cannot design well. They may be familiar with the theory of design and be able to make contributions, but they will not be able to synthesize their knowledge to generate good interfaces.

In evaluating staff candidates, questions about design principles may evoke excellent theoretical responses from analytically oriented people with no design capabilities. The individual may have worked on very successful design teams. However, other practitioners may have completed the actual design work. Thus it is essential to see each applicant do some design work yourself, and to evaluate the results.

There is a science to quality user experience design work—to the research, the methodology, and the many hundreds of design principles. But such work also has an intuitive side. The practitioner must pull these insights together in a “moment of magic.” There is a huge disparity in candidates’ abilities to perform this type of integration. Ideally, the practitioner should maintain a clear focus on the business goals and the overall context of the design. He or she must have a high-level model of the user’s characteristics, limitations, and taskflow, and must generate the interface so that it fits the shape of those activities and needs. This is not to say that someone can do good design by pure intuition—process and science are needed. But there is indeed a step beyond the science. If you want staff members who are designers, look for the ability to take that intuitive step in synthesizing the results and creating the right solution.

Specialist versus Generalist

You might find someone with a doctorate in applied psychology who has a respected academic position, a long list of publications, and many years of successful experience working in a large company. This person may be the world’s foremost expert in the psychological refractory period (the reaction time delay in stopping an action) as applied to handwriting errors. None of this background, however, guarantees that the candidate can do routine user experience design work. If handwriting is core to the business, this person may be a worthwhile specialist to add to your central usability team. Nevertheless, you should not expect him or her to be able to complete general usability activities, such as mentoring staff in development activities or developing quick tactical interface solutions under pressure.

It may be the case that specialized expertise in the field translates to general user experience design skill, but more often no such connection exists. Rather than making assumptions based on someone’s CV, test applicants carefully for both general skills and design skills.

Real Skills and Knowledge

This chapter has discussed the skills and knowledge essential for effective practitioners. These essentials are not necessarily agreed upon, however, or even well known by those who consider themselves specialists.

Some people believe that if they have interviewed users one time before writing HTML code, they have done user experience design. Others feel that if they have gotten feedback from users about their design—or have read books and even attended conferences—they are experts. If you ask these people questions, they may be able to provide a strong series of impressive responses. They may tell you that they “weave a tapestry of user experience,” provide examples of data gathering with users, and perhaps offer up a few buzzwords like “ethnographic research” and “user journey” from the latest magazine articles. However well-intentioned and forward-looking these people may be, they do not possess the skills, knowledge, methods, tools, and resources to deliver on their promises. Put in a position of control, they will create flashy sites with unusual designs. They seem to be plausible candidates, but their work will confuse and frustrate users. Their designs are likely to fail, creating a big loss for your organization and your user experience design department. Unfortunately, this lack of skills is often not evident until it is too late.

There are a few easy ways to detect this type of unqualified applicant. First, these candidates will rarely make any reference to research or describe how to access studies in the field. Second, they will rarely have a systematic methodology. They will talk in glowing terms of understanding users, but they will not have a process with clear activities and deliverables. Pay special attention to the lack of deliverables. Without concrete deliverables, it is very difficult to determine whether user experience design is being practiced properly. (While some tout “bargain” methods that are agile and drop the need for deliverables [c.f., Gothelf and Seiden 2013], these approaches are plausible only for very small programs. In almost all other cases, mature and systematic user experience design is faster, cheaper, and better for serious design work.) Finally, these applicants will rarely discuss concrete metrics. Good usability work is done to reach specific objectives. These results may take the form of a drop-off rate, efficiency, reduced training costs, and so on. Instead of describing the need for these kinds of results, this type of candidate will most likely offer flowery descriptions of a good user experience.

Interpersonal Skills and Level of Expertise

User experience design specialists depend on good relationships with the development team to perform their work effectively. A specialist may have deep knowledge, good insights, and a vast capacity for efficient design, as well as a thorough and systematic approach to his or her work. If he or she lacks good interpersonal skills, however, the organization will actually receive little value.

It seems almost unfair—there are so many requirements for good practitioners. They need knowledge of the literature, methodology, and design sense. On top of that, they must work well with others in a team. New recruits face real challenges in being accepted. If you bring in an experienced, high-powered practitioner whose expertise is far beyond that of other team members, he or she may be marginalized by the team as a defense tactic. Having a really brilliant professional on a mediocre team often makes other team members feel inadequate. What is the answer to this dilemma? The best solution is to ensure that you have a top-quality staff throughout your team.

In some cases, however, you will be hiring specialists for a team that is less than world class. They may be building fairly routine applications, or their work may be less than mission critical. In this type of scenario, consider recruiting a good, solid professional whose skills are not too advanced beyond those of the other developers. A mismatch in expertise relative to the rest of the team can cause problems, which may then be blamed on poor interpersonal skills. Remember that matching levels of expertise and good interpersonal skills are both important.

An Offshore Model

Given all the challenges that may prevent organizations from locating and hiring high-quality user experience design staff, other options may need to be explored. Once the benefits of good experience design are understood, its use may spread in a viral fashion. There is likely to be a rapid, project-level increase in demand for the application of user-centered engineering practices, which often puts unmanageable pressure on the user experience design staff.

The inability of the internal usability staff to keep up with the demand for support is a choke point. The model does not scale up easily.

Such understaffing typically occurs because, as mentioned previously, well-trained user experience design specialists are difficult to find or very expensive. Ramping up the expert internal staff required to meet the increasing demand can be prohibitively expensive and time consuming. Consulting companies may provide support for overstressed internal staff, but the cost of using consultant-based support for routine and sustained user experience design activities is prohibitive. The need, however, is critical. Without sufficient staff to do the work, institutionalization will falter. Companies could continue to apply user-centered design principles to a small range of projects, but the lost opportunity cost of such a strategy is huge. Finding cost-effective staff offshore can provide a scalable solution.

The Challenges and Success Factors of Offshore Staffing

HFI has been running large-scale offshore teams since 2000. Offshore staffing works well when you have a mature operation that follows systematic practices. It is necessary to have the offshore team properly trained and managed—and you must know what the team can do and how much it needs to travel.

You can avoid many of the communication challenges that can be experienced with an offshore model when you establish an organizational structure that meets the four core requirements for project success:

1. Effectively managing remote resources (both people and technology)

2. Ensuring an accurate and shared understanding of conventions, assumptions, and project goals

3. Maintaining quality of work standards

4. Delivering on schedule

Today’s offshore models include components designed to help meet those requirements. Some elements relate directly to the specific development process and are explored in depth in other chapters of this book:

• A systematic, trackable methodology ensures that projects proceed smoothly.

• Process-specific tools reinforce correct use of the methodology.

• Technical certification through training ensures an understanding of the methodology and tools.

Factors unrelated to the specific development process are equally important:

• The technical infrastructure is secured with sufficient redundancy (e.g., backup generators and multiple internet access providers).

• Bidirectional cross-cultural education is designed to address both day-to-day interactions and critical escalation paths.

Communication between local and remote team members is improved when the project team includes the following roles:

• A single company-resident project contact point

• An offshore project team leader sensitized to native interaction styles

Communication between local and remote team members is not limited to interactions between these two individuals, but they should be aware of all communications flowing back and forth between various points of contact. This oversight ensures that collaboration is integrated and that the priorities and efforts of the remote team stay focused. An object-oriented approach and a toolset that manages document sharing and will make communication more efficient.

At HFI, we have been able to demonstrate that offshore teams can successfully complete all of the following user experience engineering activities (there are a few points where staff will need to travel to complete key tasks):

• Expert reviews

• Usability testing (in person and remote)

• User interface structure design

• Standards development

• Prototype development

• Graphical treatment

• Detailed page design and layout

• Graphic library development

• Implementation/508-compliant3 coding

3. “508” refers to Section 508 of the Federal Rehabilitation Act. Section 508 mandates certain accessibility guidelines for federal agencies. For more information, visit www.section508.gov.

Integrating a well-trained, well-managed remote usability team significantly increases the productivity of the organization as a whole. Furthermore, creating and training a remote usability team provides a cost-effective release for the staffing chokehold.

The Limits of Offshore Usability

Despite all the benefits that can accrue from use of effective offshore teams, they cannot maintain the internal momentum for user experience design work. These practitioners can carry much of the development load, but they are not in a good position to be evangelists. There must be internal staff to maintain momentum and ensure that user experience design is not marginalized.

Summary

This chapter outlined a few of the roles important to the ongoing efforts of your central user experience design team, and offered strategies regarding what to look for when hiring staff. For organizations committed to making user-centered design central to the development cycle, a well-trained and -managed remote team can provide the capacity to scale internal resources while establishing an institutionalized operation that is practical, successful, and cost-effective. The quality of your staff will play a big part in determining the success of your efforts and the reputation of your team. The next chapter provides specific information on strategies that will help you manage increasing demands across a variety of projects.