Institutionalization of UX: A Step-by-Step Guide to a User Experience Practice, Second Edition (2014)

Read This First!: Cultural Transformation

![]() This is a journey to create a user-centered organization.

This is a journey to create a user-centered organization.

![]() Change your organization’s focus from building lots of functions to meeting user needs.

Change your organization’s focus from building lots of functions to meeting user needs.

![]() Change your organization’s focus from developing cool and impressive technology to creating software that is simple, practical, and useful.

Change your organization’s focus from developing cool and impressive technology to creating software that is simple, practical, and useful.

![]() Help executives and project managers focus on the value of user experience design.

Help executives and project managers focus on the value of user experience design.

![]() Customize and follow a systematic and complete process for institutionalizing user experience design.

Customize and follow a systematic and complete process for institutionalizing user experience design.

You are embarking on a program to institutionalize user experience design in your organization. What is the long-term view? You may find that your company already has some of the organization or groundwork in place, and you may be well on your way to establishing a user-centered process. This book can help you get all the way there—that is, to a full, mature practice. If you are starting from scratch, you can expect it to take about two years before the full implementation is in place and user experience design has become routine. Significant benefits and progress will occur before then, however, and you’ll recognize and appreciate gains as you work toward full implementation.

Of course, some setbacks may occur along the way. These almost always come in the areas of mindset, relationships, and communication. Remember that we are changing the way people think about design. We may move control of the design process to a new set of user-centered staff, and those changes can be contentious. Even so, these setbacks will illuminate the deep issues that you must work on continuously. These issues are explored in the first chapter of this book and are not fully covered in the following chapters, which explore infrastructure components, staffing requirements, and other activities. We will talk about cultural change here because it transcends the surface level and permeates the whole initiative. Addressing these issues involves shifting the core belief system of your organization, and that is why they are so important to consider early in the process.

For decades, a major thrust of the user experience field was to train developers to create better interfaces. Today, however, there is a clear global understanding that user experience design is best done by specialists in the field. The user experience design field is quite complex, skill intensive, and always growing. For these reasons, it generally does not make sense to have these responsibilities be the part-time job of a developer or business analyst. In addition, the characteristics of a good user experience designer are generally very different from those of a developer. It is a bit like asking the engineer who specializes in the tensile strength of steel to design the architecture of a building, decorate the entrance, and arrange the flowers on the side table. In our case, the business analysts and technical staff need to accept the user experience design staff and work with them effectively.

Unless the internal environment is changed through training and repeated showcase projects, there is a large natural disconnect between the viewpoint of the user experience design staff and that of the technical development team. It’s not unusual to experience some conflict and misunderstanding. If developers or business analysts have been doing the interface design, they will be attached to their designs, so criticism will likely create hard feelings. People also tend to be attached to their design decisions (like the use of tree-view menus as a solution to all navigation). People see the world in terms of their own context, and it can be difficult to get them to see the user’s viewpoint. What is even harder is taking control of the user experience design from staff who have previously had control over these decisions (even if their skills, processes, and tools did not allow for a successful outcome). Certainly, it is possible to train, and have some user experience design tasks be done by technical staff or business analysts. Nevertheless, the control of the user experience design effort must always be placed within a central user experience design group.

Once you realize the value of user experience design engineering, it is difficult to be patient with those who haven’t made this leap in understanding. But ignoring the hard work of shifting others’ perspectives makes it likely that all your accomplishments will do little. Good standards and facilities will sit idle if these deeper shifts fail to happen. The following section explores the deep changes that the real institutionalization of user experience design requires.

Changing the Feature Mindset

A deep philosophical change must take place in the shift to user-centered development. Most companies build applications intent on meeting a given time frame and providing a specific level of functionality. There is a whole flow of feature ideas, but this flow is not really user centered; rather, it is usually a combination of executive inspiration and customer comments. So how can a selection of features based partly on customer comments and requests not be considered user centered? Certainly, customer comments need to be considered (mostly as a way to discover bugs). But listening to customer comments merely gives the illusion of listening to the user. In many situations, these “customer” requests come from executives, marketing departments, or sales staff. They are not in any way representative. The real user is not studied or fully understood by most of these well-meaning “user representatives.” In other situations, comments do flow from actual users. The users may share ideas, but typically only very happy or very angry customers send feedback. Also, these comments tend to focus on features, rather than the overall design, error handling, page layout, or other user experience design issues. The result is the design of features that may not represent the needs of the majority of end users and may not address the application as a whole.

It isn’t enough to just apply standard user experience design techniques such as user experience design testing, because just applying techniques does not address the underlying issue. There is still a need to change the focus away from functionality. Software developers often build applications that have unneeded functions. They focus on completing a checklist of features for each product. Unfortunately, a clutter of irrelevant features makes the product harder to use. The whole focus of the development team is on creating all these functions on time, but if those functions are not needed or cannot be used, is timeliness so important?

It will take some work to get your organization to understand that the function race was one of the roads to success in the 1990s, but is no longer critical. Certainly, users want features. Some users focus on obtaining the maximum set of features and actually thrive on the challenge of learning their operation, but they typically comprise a small group of early adopters. In this new millennium, software and website developers must deliver adequate features that are simple and useful. Most users want information appliances to be as easy to operate as a toaster—practical, useful, usable, and satisfying solutions. Achieving this feat requires a broader change to the mindset of design and development.

Changing the Technology Mindset

Most people who work in information technology (IT) love the technology. They are in the field because technology is fun, challenging, and impressive. The developer’s job is to understand the technology and use it. Therefore, developers naturally focus on learning about the technology, and they feel excited about using the latest, most powerful facility. To a degree, this bias creates development groups that are more focused on creating something impressive and cool instead of practical and useful.

Knowledge of the scientific principles, together with working with user experience design engineers, helps create a major shift in the way that IT professionals see technology. Technology is a tool that lets you meet user needs. Much like a professional carpenter who picks the tool that best meets the need and does not anxiously seek an excuse to use the latest hammer, developers need to focus on creating the design that customers need, rather than just exercising the software technology that will make them feel proud.

The people who have to use the things we design may not be using a product because it is new and fun. Although there are always early adopters, most technology users want to use your design to get something done—get information from a website, pay their bills online, or look up directions, for example. Most users are not looking for technology that is challenging and interesting; instead, they want the result to be useful and interesting. In fact, many users expect the technology to be not challenging but actually transparent. Professional developers are often intrigued by the technology and its quirks. Users often find the same quirks annoying.

Changing the Process Mindset

In organizations that are dominated by business analysts, the focus can be on defining and optimizing efficient processes. This approach might sound like it would be a good one from a user experience design viewpoint. In fact, there is a very big difference between efficient processes and customer-centered design. You might create a generic account origination process that covers all the functions necessary in a very efficient way. There might even be efficiencies put into place, such as the concatenation of multiple account origination requirements so that the user will never have to enter the same data twice. But would this be optimized from the user experience design viewpoint? It might not. The user might need to think about each account separately. It might make more sense to customers to configure each account as a unit, because they think about each account separately. In contrast, a logical functional model might have the beneficiaries set up all at once and then the alerts established all at once. The functional analysis would also probably include the customer’s data (e.g., name, addresses) first in the flow, as this is more logical. But user experience design experts know better than to implement this model: You want to first configure the accounts so that the customers feel ownership and have an investment in their acquisitions. Only then should the application ask for the boring registration details. In this way, customers become invested in the accounts and are unlikely to abandon the application.

Business analysts with a functional viewpoint can be wonderful supporters of a user experience design effort. With training, they can really contribute to the design workload. Nevertheless, an organization that is focused on process efficiency needs to be brought around to see that success requires much more than a functional viewpoint.

Changing the Graphics Mindset

Good-quality visual design is often an important part of a successful user-centered design. It generally increases trust. Moreover, visual designs that are developed around focused persuasion engineering strategies are very powerful. But visual design is only a small part of what it takes to be successful in user experience design. In fact, interesting counter-examples can be cited. A target population such as “youth,” for example, would seem like a natural fit for exciting graphic treatments. Yet Facebook is wildly successful with youth, even though its graphics are limited and unimpressive. Why? Because Facebook fulfills a set of fundamental needs for youth.

Some organizations equate user experience design with rich and polished graphics. When this is done without exploring the underlying strategic and structural design, it is like putting lipstick on a bulldog. The results are not pretty. Executives are often focused on the appearance of the design, but this is a common mistake.

Some executives seem really wedded to the graphic issue. In a way, this emphasis might simply reflect the fun of doing uncontrolled graphic work, much in the same way that people love to select colors for their house or clothing. In classic visual design work, the graphics team often focuses on creating a design that pleases the executive. Their criterion for success is that the executive likes it. In such a case, the graphics team creates one good design and two bad designs, and then they hope the executive picks the good design from the lineup. There is no real measurement of success, so the process of graphics development can be free, easy, and entertaining. In contrast, in serious graphic development, the design needs to be informed and validated. The criteria for success, in turn, are based on observed user behavior.

Graphic designers can be trained and can learn to do the more analytic and interpersonal work of the user experience design practitioner. Even the most sophisticated creative directors, however, do not have training in the user experience design field.

Executives

Today, it is hard to find an executive who does not care about customer experience. As executives around the world play the chess game of business strategy, most of them are having the same realization: Every organization can get hardware that works (usually better than really matters), and every organization can get software to run and not crash and hold tons of data. Thus, there is now one primary differentiator among companies in the digital space: customer experience. Today, the organization with the best customer experience wins.

Top executives are usually determined to optimize their organization’s customer experience, but they usually try things that don’t work well. They give passionate speeches that address caring about customers, with sweet stories describing how their kids were treated in Disneyland. In reality, the problem with digital customer experiences is not a problem with staff motivation. Being motivated does not make for good designs. Being motivated without the training, and certification, and methods, and standards, and tools of the user experience design field just makes for dispirited staff—and shouting at them until they panic just makes things worse.

Some executives get frustrated, rip off their ties, roll up their sleeves, and start designing interfaces themselves. Of course, most executives have no human–computer interface design skills. What they create makes sense to them (because they know what it’s supposed to do), but it rarely makes sense to the users.

Some executives think that “customer-led design” means design work that is “led by customers.” As a result, they arrange for real customers to be a part of the design process. Unfortunately, users are not designers, so they don’t know what the designs should be. Also, the users allocated to the design committee are really never representative (you tend to get either users who are experts in the software or users who are below average and therefore expendable). In addition, the users quickly become less representative as they learn the organization’s viewpoint and language, so they quickly stop being even a good source of insight into “how things are” (subject-matter expertise).

Exhausted by the effort, senior executives finally turn to other key areas such as security and advertising. They decide that user experience design is a mystical thing and hope that a miracle occurs. With luck, the scattered user experience design people in the organization will climb up the organizational structure and share a clear understanding of what it takes to make an industrial-strength practice in user experience design. Otherwise, the whole initiative dissipates—perhaps to be reinvigorated later by a startling loss in market share, wasted design efforts, or a change in leadership.

When presented with an understanding of the requirements for the development of a mature practice, many top executives become very excited and want to get started right away. It is a challenge to persuade them to carefully plan the overall institutionalization process. In many cases, they may demand to start something tangible, at which point they typically kick off a user interface standards program. Even worse, they may insist on persona definitions (at the end of which, no one will be sure why you spent so much money). This “Ready, fire, aim!” approach results in an inefficient, uncoordinated, and unreliable path to a mature practice—so please insist on a strategy before serious investments start.

Changing Middle Management Values

While the development community makes the move away from fixation on features and new technologies, middle management must also change. Management is used to asking whether milestones are met and budgets are under control and establishing compensation schemes that reinforce the need to produce functions on schedule. This approach has worked well in the past, but it won’t work well in the future. Things that were thought of as secondary intangibles and “nice-to-haves” must be quantified and managed, because those “soft” design capabilities are now the key to the organization’s future.

Management must understand that the company is building not just systems that will function, but also systems that will work in the context of a given range of users, doing a given set of tasks, in a given environment. Success is measured as the real business value of the application. Achieving success takes much more than just delivering the website or application on time. The deliverable must be usable and satisfying to operate. In many cases, the emotional engagement and resulting conversion of customers is the real target. And it is not enough to simply make designs that are easy to operate. The target outcome of the design will depend on the organization and may include increased sales or enrollment, more leads, increased willingness to pay fees, larger sets of items per purchase, and so on. These are the results that user experience design buys you. Few organizations will not directly benefit from good user experience engineering.

Once organizations realize that user experience design is a key area in ensuring their success, they sometimes will charge executives with making improvements, which is great. Unfortunately, they often compensate those executives based on moving the results on a customer satisfaction survey up a fraction of a point. This is not quite right, as customer satisfaction ratings don’t really equate to user experience design quality. Instead, they are more like a rough indication of whether the customer’s expectations are met. You can probably lower a customer’s expectations and get a nice jump in satisfaction.

Advice for Those Considering an Investment in User Experience Design

Harley Manning, Research Director, Forrester Research

The single biggest gap in knowledge we see at Forrester is a lack of understanding of what and why. What makes for a great user experience, and why you should care—tied to numbers. That’s the great barrier. People must understand that there are objective methods of improving user experience and that user experience moves business metrics.

The second biggest gap is a lack of the right skills. We see a hierarchy of skills, process, and organization, where skills are the most important. Whether you try to do this kind of development internally (which is a trend we see) or hire out, you still need somebody on the inside with a deep clue. Otherwise, you’re not going to follow the right processes, even if you have them in place, and you’re not going to hire the right vendors or manage them effectively.

Regarding processes, there are many good processes out there—just pick one and use it consistently. I was talking with the Web development team at Michelin Tire, and I said, “You guys don’t wake up in the morning and say, how should we manufacture tires today, do you?” And they said, “Of course not, but we never thought of a website that way.” They’re smart—as soon as I said this, they got it.

Business schools have always taught about marketing issues and brand management, but now they must go further. Marketing can point out a potential market niche; user experience engineering can help build a product that will reliably succeed in that niche. The implications of poor user experience design can be catastrophic for a company. It therefore makes sense that executives and senior management attend to this critical success factor. Project and business line managers are interested in identifiable metrics. As user experience design matures within an organization, it is not enough to occasionally review the latest “customer satisfaction rating” or “net promoter score.” Depending on the type of website or application, managers must be concerned about task speed, task failure rates, drop-off rates, competitive metrics, return on investment (ROI), retention rates, and other factors. Executives must be aware of and support a user-centered process. Perhaps most importantly, middle managers must care about user experience and performance levels as an essential success factor.

Changing the Process for Interface Design

Many companies expect developers to sit down and just draft the interface design without doing expert reviews, data gathering, or any testing. If your organization currently uses this approach, you must be willing to learn and use a different approach. User interface design must be an iterative process. You sketch and prototype an interface, then change it, then get feedback from users, then change it, again and again. There are two reasons why effective interface design must be iterative:

1. Design is a process of deciding among many sets of alternatives. Getting them all correct the first time is impossible.

2. As users see what an interface is actually like, they change their conceptions and expectations—so the requirements change.

User interface design, by its very nature, is too complex for anyone to accomplish successfully without feedback. Even user experience design professionals with decades of experience don’t expect to sit down to design a screen and get it right the first time.

User Experience Design within Government

Janice Nall, Managing Director, Atlanta, Danya International, Inc. Former Chief, Communication Technologies Branch, National Cancer Institute

There are probably three or four core things we have done to institutionalize user experience design. Number one is involving the leadership—through presentations and participating in testing or showing them results of a usable site versus an unusable site.

Number two is using the language from leaders driving the new trend to e-government. Because the National Cancer Institute is part of the government, it helps to be able to tell our leadership that user experience design and user-centered design are supported, from the president of the United States to the Office of Management and Budget to the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). Using their own words, language, and documents has been very powerful.

Number three is training, which has been hugely successful—a way to institutionalize user experience design across HHS and the federal government. We believe in teaching people to fish rather than feeding them the fish. We also use tools and resources, like the Research-Based Web Design and User Experience Design Guidelines, to teach them.

Number four is our list of about 500 federal people who receive our online publication U-Group (shorthand for user experience design group) via the U-group listserv. Through this listserv, we are trying to get current information out, and we’re saying, “Let’s share information; let’s collaborate”—encouraging people to share lessons learned.

Everyone developing software and websites needs to remember that both development and design are iterative processes. Being brilliant does help, but the willingness to get feedback and apply it selectively is more important. Designers must be willing to learn and create better designs each time, and organizations need to have a culture that supports such iterations without blame.

The Step-by-Step Process for Institutionalizing User Experience Design

The final deep challenge is the tendency to address user experience design in a piecemeal fashion. Many companies that see the value of user experience design still attempt to address it with a series of uncoordinated projects. Instead, there must be a managed user experience design effort. This section outlines the process covered in this book. It is gleaned from experiences of working with hundreds of companies across thirty years within the field of user experience design at Human Factors International, Inc. (HFI).

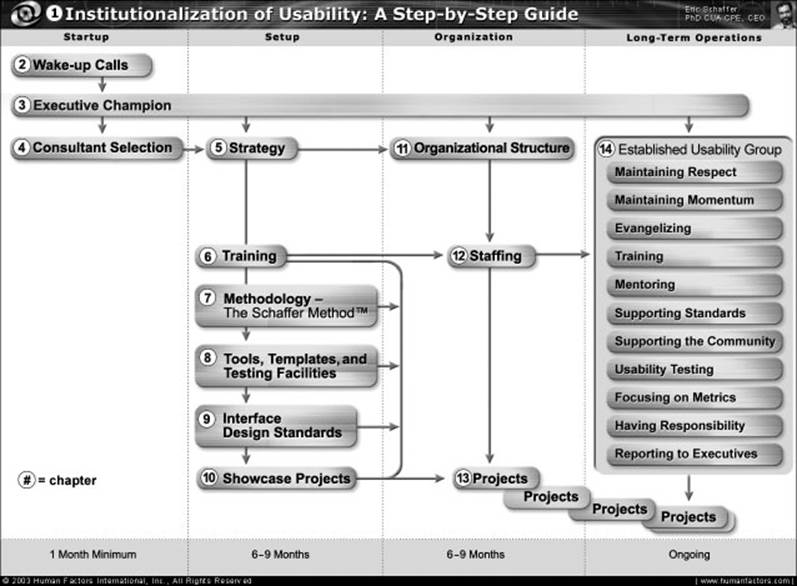

Figure 0-1 illustrates the typical flow of activities for institutionalizing user experience design in an organization. You need to make sure these activities fit with your corporate culture and circumstances. In fact, you cannot hope to be successful if you treat this process as you would treat steps within a simple kit. To succeed, you must proceed consciously and creatively. Since 1981, HFI has worked with many companies and organizations that have not institutionalized user experience design yet and many others that have made this transition. Based on thousands of projects and experiences with hundreds of clients, HFI has distilled, tested, and refined the key elements that lead to success. Hundreds of companies, large and small, have followed this process and experienced more efficient user experience design methods and processes, as well as more effective products and applications.

Figure 0-1: Overview of the institutionalization of user experience design

The following sections briefly describe each of these phases—Startup, Setup, Organization, and Long-Term Operations. Later chapters discuss each step in detail.

The Startup Phase

In the 2004, in Institutionalization of Usability, there was a whole section on how a company needed to experience a horrid disaster to provide a wake-up call. Only then would the organization really move forward. Today that is no longer true—user experience design is becoming a recognized global best practice in development. Nasty wake-up calls are no longer needed. Instead, enlightened executives can often understand the need based on their past experience and education as managers. Even so, the key to success with such a venture remains the identification of anexecutive champion. This person provides the leadership, resources, and coordination for going forward. This person takes the wake-up call to heart and moves institutionalization forward within the organization. The executive champion must be at a high enough level in the organization to motivate coordination across the siloed groups that affect customers. That person must also be able to influence the total development budget.

It is challenging to start a user experience design institutionalization program from scratch without help from a user experience design consultant who has experience, training, tools, intellectual property, and an established team. To establish this program, you must have or create an internal user experience design manager and an internal team—but you will need help from a consultant to set up a serious practice. Selecting a consultant is important because you need to find a person or company that has the skills and infrastructure to help your organization move ahead quickly. The consulting organization will often have to meet immediate tactical needs, complete showcase design projects, and concurrently set up your internal capabilities.

The Setup Phase

We always tell organizations that “Well begun is half done.” When you set up a hospital, there are lots of interdependent systems that need coordination (e.g., walls, pipes, elevators, cables, operating manuals, and organizational designs). It is much the same with a user experience design practice. First, you need a strategy that fits your organization. The strategy should be specific about what will be done. It should include the timing, sequence, validation, and funding that will be necessary for your user experience design program to be successful. You may prefer to start with a short-term strategy that establishes the basics and then let the strategy evolve over time, or (ideally) you may develop an all-encompassing, multiple-year project plan.

Every company has a methodology for system development. It may be home-grown or purchased, but in either case the existing methodology is unlikely to do a good job of supporting user-centered design. It is important to have a user-centered design method in place—one that is integrated with current methods and accepted by management and staff. Otherwise, there is no common road map that will pull user experience design engineering into the design process.

Interface design standards are usually a high priority in the institutionalization process. Standards are easy to justify because they help both the developers and the user experience design staff. Even if you have several user experience design staff members on a project, you will likely have poor results if standards are lacking. The experts may independently design good interfaces, but their designs will be inconsistent and incompatible. Moreover, if the standards are not developed quickly, there will be an ever-growing installed base of inconsistent designs.

Without a central standardized set of user profiles and ecosystem models, you will find yourself paying to repeat research. And what is worse, the research you do will probably be underfunded (because it is justified by just one single project) and, therefore, will provide a weak set of insights about customers. It is far faster, cheaper, and better to have a central model of your customers and staff. Research can then be carried out and added to this model. In turn, the model gets richer and richer instead of accumulating a daunting stack of reports.

There is a whole toolkit of tools, templates, and testing facilities that you need to be able to work with effectively as part of user experience design. This toolkit should include a venue for testing, templates for questionnaires and deliverables, and user experience design testing equipment.

Of course, it makes no sense to have methods, standards, and tools if the skills to use them properly are lacking. The initial strategy for institutionalization of user experience design should include training and certification for in-house staff. You can provide general training for the development community and more extensive training and perhaps certification for those individuals who will be interface development professionals. Out of this training, staff who are talented and interested in the user experience design field will probably emerge.

During the Setup phase, it usually makes sense to have one or more showcase projects. Conducting these projects provides an opportunity for the infrastructure, training, and standards to come together, be shaken out, and be proven. Such projects also offer a chance to share the value of user experience design with the whole development community.

The Organization Phase

With successful completion of the Setup phase, you have a solid and proven infrastructure for user experience design work, methods, tools, and standards, as well as a process that works. At this point, you need to ensure that the practice can operate effectively within the organization. The main issue to pay attention to is governance. Will the user experience design practice be brought into your design programs? Will the recommendations and designs from the team actually be used? Will there be metrics that ensure that everyone focuses on user experience as a key area? Each of these questions springs from serious challenges faced by organizations worldwide. If a set of appropriate measures is not taken, the problem of governance will likely derail the entire effort.

It remains important to follow the organizational design principle of spreading user experience design throughout your company or agency. User experience design should not reside within a single group or team; instead, to succeed, user experience design must permeate the entire organization and become part of the system. In all cases, you need a small, centralized, internal group to support your user experience design initiatives. For medium- and large-sized companies, user experience design practitioners need to report to specific project teams. The executive champion needs to establish the right placement and reporting for the group and the practitioners.

The Organization phase is the appropriate time to start staffing the organization. Now the full process of user-centered design is working within your organization, and you can see the best way to put a team into the framework. The steps you went through in the Setup phase provide a clear understanding of the types of people needed. Remember that about 10% of your development headcount should be user experience design professionals.

When establishing a central user experience group, it is best to pull together a critical mass of your strongest practitioners. In the prior training process, there is a good chance that several people will have stood out. This is part of the reason that the internal organization is generally established after the initial training—it provides an opportunity for the best internal staff to join the team. It is usually important to hire some additional highly qualified user experience design staff. In this way, the organization benefits from both insiders who know the corporate culture and outsiders who are more knowledgeable about user experience design technology. A manager of the central user experience design group should be the main “go to” person for the user experience design staff.

With the user experience design staff in place, it is time to apply user experience design methods to a whole wave of projects. Doing so delivers immediate results and value. It will soon be possible to have every project completed with appropriate user-centered design methods, but in the immediate future you are likely to need to manage a shortage of user experience design staff. To remedy this problem and to cost-effectively manage large volumes of user experience design work, offshore user experience design teams can be a worthwhile addition to the overall staffing strategy.

The Long-Term Operations Phase

The established central group now has an ongoing role in supporting the user experience design engineering process. This role includes the maintenance of the user experience design infrastructure and skill sets within the organization. User experience design practitioners should now be involved in all development work, following the user-centered methodology and applying the resources established in the Setup phase and continually updated by the central user experience design team.

As the user experience design institutionalization effort matures, the relatively informal executive champion may give way (or be promoted) to the chief user experience officer (CXO). This is not a chief user experience design officer, but rather a broader role. The CXO is responsible for the overall quality of customer experience. Being a CXO requires expertise in user experience design, as well as a thorough understanding of many other disciplines, including aspects of branding, marketing, graphics, and content development. The CXO must be able to reach across lines of business to ensure compatibility of presentation and messaging. If the role of CXO is not established, the central user experience design team should be placed under some executive organization, such as marketing, and the company must ensure that the team members receive good executive stewardship.

Summary

In choosing to set an institutionalization process into motion at your organization, you are choosing to change the feature mindset, technology mindset, management values, and process for interface design that previously governed your operations. This bold move requires the commitment of staff and resources. Organizing your activities to align with the step-by-step process outlined in this book will help ensure visible progress. While this book presents a step-by-step approach, clearly this sequence may vary at specific organizations. Most organizations must face the problem of “changing the wings while the plane is in flight.” At HFI, we must often use our own staff to meet our client organization’s immediate needs, while we concurrently develop internal capabilities. This is not all bad, as we can use the immediate programs as a training opportunity for internal staff and as a proving ground for methods and standards.

Chapter 1 outlines some of the more typical wake-up calls to user experience design that companies experience. An exploration of some of the more common reactions to these experiences is valuable for capitalizing on initial momentum.