Designing Connected Products: UX for the Consumer Internet of Things (2015)

Chapter 5. Understanding People and Context

BY ELIZABETH GOODMAN

Most people do not have limitless funds and patience for untried products and services. They tend to have habits that they don’t want to change. They have limited budgets. They are not enthusiastic about learning new technical skills. Moreover, they have an inconvenient tendency to ask themselves whether a new purchase is really worth the effort, expense, and disruption to their routines. The answer to this question, as many makers of connected products have found, is usually “no.”

In this chapter, we’ll show how early engagement with potential customers and users can help you set up connected products and services for mass-market success and avoid expensive and wasteful failures.

This chapter introduces:

§ Concepts and questions to guide early investigation of potential audiences and contexts of use (Initial Questions and Concepts)

§ Methods and tools for answering those questions (Techniques: From Asking to Watching to Making)

This chapter addresses the following issues:

§ How to define product roles beyond that of “the user” (Actors, roles, and expertise)

§ Why it’s important to identify where needs and roles conflict (When needs conflict)

§ What contextual factors matter most to connected product design (The Context of Interaction)

Throughout this chapter, we’ll be using a hypothetical home security design project to illustrate key points.

NOTE

This chapter focuses on questions and methods specific to connected products and services. If you’re not already familiar with more general product design research methods, try supplementing this chapter with a short introduction to the field, such as Just Enough Research, by Erika Hall (http://abookapart.com/products/just-enough-research).

The Role of Research in Connected Product Design

Consider the sad career of the “smart fridge” (Figure 5-1).

Figure 5-1. The Electrolux Screenfridge, 1999 (image: Electrolux)

Despite massive publicity attending each launch, no “smart fridge,” from the 1999 Electrolux Screenfridge to the 2012 LG Smart ThinQ, has ever attained market success. By 2014, the SmartThinQ was discontinued. Yet every few years, a new smart fridge has appeared. It’s amazing how many obviously intelligent and talented people keep sinking resources into an idea whose time just never seems to come.

There’s no way to guarantee success. But the best way to avoid making the next smart fridge is to remember that you are no different from those intelligent and talented people. The best way to avoid repeating the past is to ask some hard questions—starting right now—about what you’re going to make, who would actually use it, and what support it needs to work. That’s the proper role of UX research. In this chapter, we’ll introduce early stage exploration with potential customers and users. Later, in Chapter 14, we’ll introduce rapid product prototyping methods to speed up iterative cycles of design, evaluation, and redesign.

Initial Questions and Concepts

Imagine you’re about to leave for a long vacation far away from your home. You’re a little worried about fire, burglars, or even just missing packages. However, none of the home security systems on the market seem right for you. You think: there’s definitely some design opportunities here.

But what kinds of opportunities? Do you want to be able to unlock doors remotely? Turn lights on and off to mimic normal occupancy? Have the house automatically alert the police in an emergency? Maybe what you want isn’t a home security system at all, but something that works more like traditional apartment building concierge, which can automatically alert a local contact if you’re away.

The options proliferate as you dream up a new home security product to suit your needs. And each product connects a different set of people, places, and things. Let’s list a few elements of a generic home security service:

§ The inhabitants of the house

§ The police

§ Any humans contracted to be on call

§ Software designers and developers, whether in house, contracted, or third party

§ The manufacturers of any hardware and casing (likely different factories, perhaps even on different continents)

§ Relevant government regulators, such as the Federal Communications Commission in the United States

§ Telecommunications networks and their associated protocols and constraints

§ Product technical support staff

§ Industry journalists

...and the list just keeps going. Users are important, but product and service design requires cooperation from an entire web of people, organizations, and technical systems. Just think about one of the earliest massively popular connected appliances—the home radio. All it could do was select the station and change the volume. Success depended on the excitement generated by radio station broadcasts.

To design connected products as successful as the first radios, we need to start with the people who will use them. But we also need to think about the web of relationships those products need to thrive, just as radio sets needed stations and broadcasts.

Actors and Stakeholders

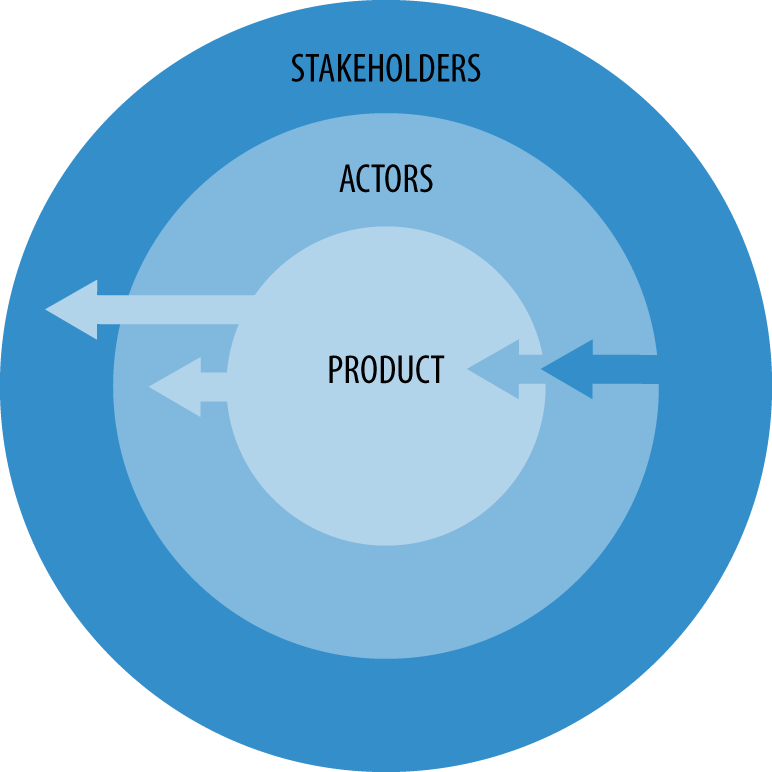

Think about the home security elements we just listed. Very few of the people on it are actually users. Some of them, such as the police, might never know the product exists. As products and services get more complicated, it’s helpful to get more specific about the kinds of people in our web. We’ll talk about two here. Actors directly handle the product. They physically touch or see it. Stakeholders are organizations or individuals who don’t directly interact with the product but who still have an interest in how it works.

But first, how not to define people

In product marketing, it’s common to use demographic attributes (age, sex, income, ethnicity, religion, etc.) to segment markets into different audiences. In UX design, actors should not only, or even mostly, be defined by demographic attributes such as age, income, or ethnicity. In fact, driving UX with demographics is generally a bad idea.

Consider this real-world example: a group of device designers at a major technology company were getting angry complaints about the error-filled data entered by long-haul truck drivers into mobile terminals. The team at first assumed that the truck drivers were uneducated and careless, and that errors were unavoidable. Yet the errors got worse and complaints mounted. Finally, in the dead of winter, a senior designer decided to hit the highways to see the problem himself.

The drivers, it turns out, could spell just fine. The problem lay in the device’s tiny buttons. The drivers were often big men with correspondingly big hands. Especially in winter, while wearing bulky gloves, hitting the wrong keys was inevitable. Unfortunately, the device provided no easy way to fix mistakes before submitting data. The solution was simple: redesign the interface to require less manual typing, and add a big OK button to aid error correction. Error rates plummeted after the introduction of the redesigned device.

Unconsciously stereotyping is easy to do when you rely on demographic statistics. It’s true that most of the truckers did not have college degrees. But that didn’t make them lazy. Or unable to spell. The problem was, ironically, related to another demographically related attribute: the median size of trucker fingertips. The designers could have lowered the error rate months earlier (and avoided irritating both customers and the truckers!) if they had done a little in-person research early on.

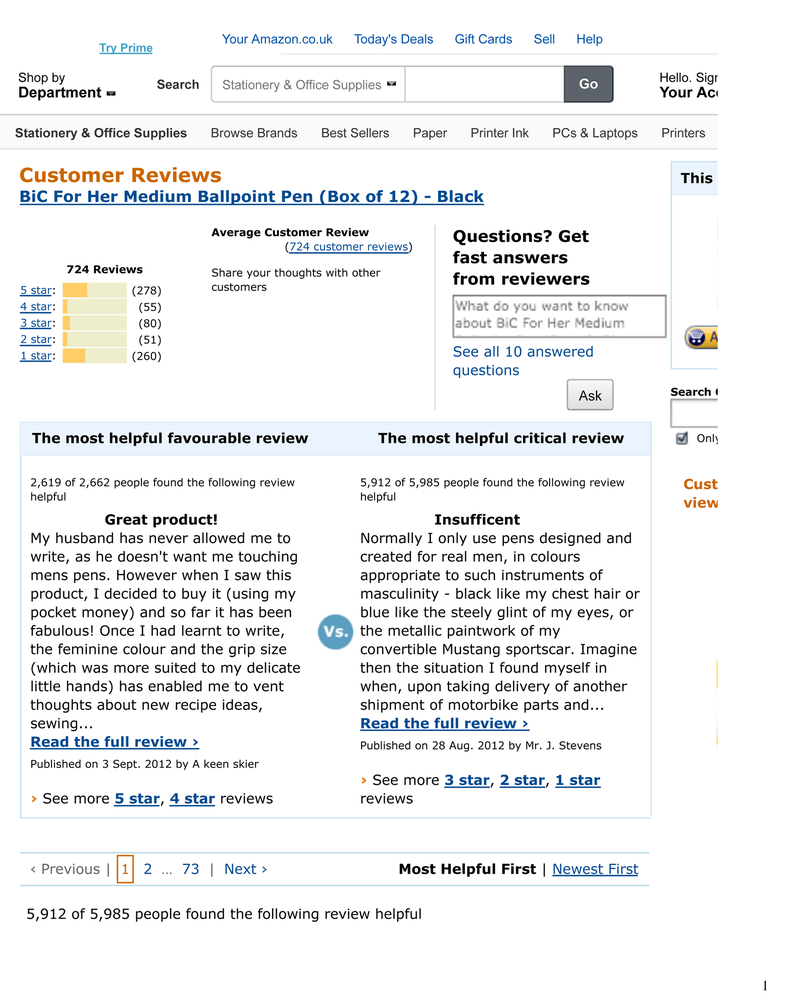

When you stereotype based on demographics, the best-case scenario yields a product that’s less useful than it could be, as with the truckers. Worst case, you end up alienating your intended audience, as with the BiC for Women Amazon disaster (Figure 5-2).

Are some relevant connected product design factors linked to demographics? Sure, including:

§ Body dimensions and product ergonomics

§ Availability of resources like time, money, or space—for example, people raising kids are likely to have less solo leisure time...although you can’t be sure!

§ Diminished or increased physiological capacities, such as vision, hearing, agility, strength, or memory[62]

§ Preferred language and other localization requirements

Figure 5-2. BiC releases BiC for Her pens; hilarity ensues[63]

However, questions about activities should drive product strategy. What do actors need to accomplish their goals? Or even: what are their goals in the first place?

When starting to study users, you may need to make some decisions based on demographic attributes, but you should focus your effort on people who likely share the same goals and needs. Demographic attributes, then, are generally helpful only insofar as they affect what users need a product to do for them—such as automate heavy lifting or give them more time to spend with their kids. The trick is to treat demographics as a source of questions, rather than a shortcut to answering them. Try asking yourself:

§ What do you think you know, based on demographics?

§ What evidence do you have for those suppositions?

If your evidence is, “Well, everyone knows that,” or “That’s just the way those people are,” then what you have is an assumption—one that you should check with research.

Without early engagement with representatives of that group, “the user” becomes a dangerously vague character. Empathizing with “the user” is unhelpful if those needs, capacities, and emotions don’t actually exist—as in the story of the truck drivers. Basing team decisions on “the user” will not help if team members all have different ideas of who “the user” is and what “the user” wants.

You can change your mind about the intended audience for your product midway through research or design—that’s what iterative design is all about. But if you never consider the question in the first place, you‘ll be guessing at what to prototype. You might also miss some market-revolutionizing functionality that a little bit of targeted investigation could inspire.

Actors, roles, and expertise

An actor can be an individual (e.g., the person using it) or an organization (e.g., a corporation selling it). To start investigating actors, map out a potential product lifecycle from design to disposal. Let’s walk through a few important actors in the life of a home security system.

There are the makers of the product: designers, engineers, and so on. Makers can also include service providers, like marketers. Makers can include vendor organizations: perhaps one or more hardware manufacturers, a software platform provider, the installation and maintenance engineers, and consumer-facing sales, support, and so on.

There are, of course, users. But even a relatively simple home security system can have a variety of user roles. Imagine a family with a teenager, a young child, and a pet cat. The parents are buyers. They choose the system and pay for it. The children only need to turn it on and off. The cat, meanwhile, is also a kind of user. If it isn’t taken into account, the alarm might go off every time it jumps through a window. What about delivery people or short-term guests? They shouldn’t have much control over the system, but do need occasional, perhaps revocable, access.

Then imagine how that same security system might work for an older person living alone, with a worried family living far away versus a set of mostly friendly but largely unconcerned housemates. If the security system is purchased for a furnished rental or collective housing arrangement, the buyer might be a stranger to the users, and vice versa. A family might have different expectations for a system installed by the parents than for a system provided by an anonymous real estate management firm.

From installation to repair, connected products will require technical support. When the security system needs repair, we encounter the technician. That technical support may come from a professional—or perhaps it is the teenager or a parent who manages the Internet provider and changes the batteries. Who will install, troubleshoot, and repair your product? What do those technicians need in order to do their jobs well?

Then, there are the actors involved in disposal. Perhaps it’s sold to another user. Perhaps it goes to an ewaste recycling facility. Perhaps plant workers have to incinerate it. Disposal is a predictable stage of a product’s life—those who take part in it safely (or unsafely) are also actors.

How expert do you expect actors to be? What kind of knowledge or skill do they have already? What do they need to learn? In rented housing with little stability, the security system shouldn’t assume transient inhabitants stay long enough to master complex functionality. A system designed for a commercial setting like a small daycare, however, could reasonably assume some required employee training.

Technical “expertise” comes in many flavors. Even if you can assume users and technicians are very familiar with security systems, they may not be so good at configuring network settings, and vice versa. So the home security product you’re designing would need to accommodate varying levels of expertise with systems for controlling access and remote monitoring. That’s where research comes in. Once you have decided what kinds of actors might be involved, you can begin to figure out what they know—and don’t know.

For users who are also buyers, the purchase process is part of the user experience. When users are not also buyers, decisions taken at the time of purchase shape what people use, and how they expect to use it. Later, user experience depends on users’—or technicians’—expertise in diagnosing and repairing inevitable technical problems. Table 5-1 lists some common questions about actors to answer with research.

Table 5-1. Starter questions about actors and roles

|

Role |

Responsibility |

Common Questions |

|

Customer/buyer |

Makes the decision to purchase the product |

Why should I buy this product? What makes it better than competitors? Is it worth the cost? |

|

User |

Triggers everyday interactions with the product |

Why do I want this product? What do I want from it? How do I use it? Is it easy for someone like me to use? Will using it change how other people think of me? |

|

Technician |

Installs, maintains, and repairs the product |

How do I diagnose the problem? What resources (e.g., information, tools, skills) do I need to fix it? |

Stakeholders

Unlike actors, stakeholders don’t directly interact with the product itself. Stakeholders can be individuals or organizations that indirectly affect how a product works, and those who are indirectly affected by its use. Figure 5-3 illustrates the relationship between actors and stakeholders.

Some stakeholders are people. Local police officers might be stakeholders in a home security system. Police officers do not buy, use, or maintain the home security system. However, how quickly and politely they respond to alarms will affect how users feel about the product. People affected by the product even though they don’t use it are also stakeholders. Neighbors irritated by constant alarms and police visits, for example, could quickly make life difficult for the users of our potential home security service.

Figure 5-3. Stakeholders and actors

Stakeholders can also be organizations. Later in the chapter, we’ll discuss laws and regulations as part of the product context. Government regulators are important stakeholders for any product that falls under their mandate—which is basically any product or service that has a nondigital component. Car service innovator Uber, for example, notoriously fell afoul of insurance regulators[64] and taxi unions. As the company grew, insurance companies no longer wanted to allow drivers ferrying passengers around all day to pay premiums based on only occasional car-sharing. And let’s not forget the angry taxi drivers facing the loss of fares!

One of the key reasons to identify stakeholders as indirect actors is to make sure you keep their interests in mind. When influence is indirect, it’s easy to overlook. But if how a product works in practice depends on the activities of the police or a government regulator, the success of your product may depend on early engagement with their representatives. There’s no sense in bringing predictable and avoidable public anger or legal prosecution down on yourself. Interviews with subject matter experts, such as lawyers and local political stakeholders, can help you identify potential obstacles and how to work around them.

When needs conflict

After identifying actors and stakeholders, we can begin to ask what our product should do for them. As always, the answer cannot be “everything” if we hope to ship a desirable, usable, well-priced product.

Ideally, you’d start by matching the needs of intended users to your own business interests and goals. For the purposes of product and service design, a need is anything we value highly. A need can be a tangible deficiency: I need to find the nearest gas station. Or it can be a more intangible aspiration or goal: I need to feel like my friends care about me. Sometimes “needs” seem frivolous to outsiders; sometimes they are literally matters of life or death. What matters for product definition, however, is that those needs are deeply felt and that you are interested in addressing them.

But what happens when deeply felt needs conflict?

Take Lively, a service that helps families monitor the physical condition of elder relatives through a connected wristband and set of sensors, and gives the relatives updates on family activities. Here’s how Lively (mylively.com) makes the case for itself:

You need peace of mind—but sometimes your family and friends need it even more.

“Peace of mind” sounds like a compelling value proposition for both the elderly people being monitored and the families who care about them. However, Lively’s value proposition also illustrates a particular challenge for connected products and services: conflicts between what different people in different roles want for themselves. Lively has to mediate a compromise between the desire of family members to ensure that a physically or cognitively impaired loved one is well...and the likely distaste of those loved ones for what may feel like spying or surveillance. If there is a fight over monitoring, who wins? The loved one? The family? Or will the family simply choose to skip the fight altogether by rejecting the product?

Lively’s challenge is not unique. In fact, it’s common. Many connected products live closely to their users. They are embedded into buildings, furniture, and cars, worn like jewellery, or even implanted into our bodies. Such products are almost guaranteed to raise sensitive questions of privacy, autonomy, and control. Sensors watch us; algorithms draw conclusions about our activities; actuators respond. We hope that the products that live with us are acting in our best interests...but whose goals are they really furthering?

In defining connected products, one of the most important functions of design research is to surface conflicting needs that might sabotage a seemingly well-conceived product or service. Not all conflicts can—or should be—resolved. It may be that one group will have to remain unsatisfied. The neighbors might just have to live with the alarms and police calls. However, the best chance for negotiating those sensitive questions is to identify where and how a product is likely to raise them in the first place.

The Context of Interaction

By “context,” we mean the factors outside the product relevant to our interactions with it—the immediate physical environment, human intentions and actions, organizational policies and legal rules, and so on. Context always matters to design, of course. But the more that products sense and respond to their surroundings, the more variable the locations and times of use, and the more dependent products are on interconnected networks—the more crucial it becomes to investigate context.

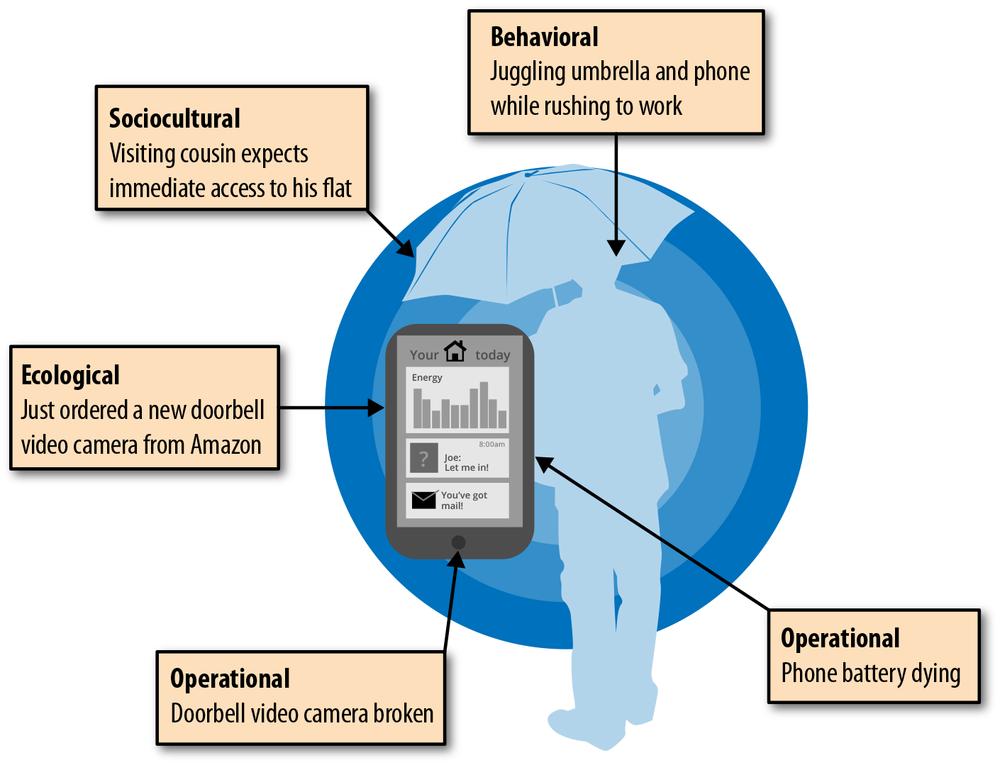

In the following section, we’ll briefly introduce four different ways to look at context: operational, behavioral, ecological, and sociocultural. Figure 5-7 illustrates how those contextual factors might play out in a home security system in which a phone application monitors a suite of devices.

Operational context

Operational context refers to the physical world outside a device plus the resources it needs to function. Most obviously, operational context includes environmental conditions (heat/cold, wet/dust). It can also include spatial arrangements, such as standard architectural dimensions or clothing sizes. Successful installation of a home security system, for example, often depends on whether the user’s doors and windows match what the maker expected.[65]What about infrastructure? Products intended for wilderness, rural, or unstable regions can’t depend on reliable or centrally maintained Internet access and mains power. Under those circumstances, a truly reliable home security system would need to provide its own power and electricity.

Payment and supply chains might also be part of operational context. If your audience can’t or won’t pay for power and network access, then those resources may be practically unavailable even if technically present. Especially in remote areas, you may need to consider the likely logistics of repair and upgrade. It’s no favor to sell a product that can’t be fixed or easily replaced.

Research on operational context can inform business and service models for payment, distribution, and repair. It can also guide engineering requirements, particularly in coping with extreme environments, unreliable power, and intermittent network access. That’s what motivates the “go anywhere, do anything” router start-up BRCK to leave their Nairobi office for what they call “expeditions” across the continent. The expeditions test whether the router can survive extreme heat, wet, dust, and vibration (Figure 5-4). As BRCK’s Philip Walton writes:

It is simply impossible to know what Africa can throw at you until you get out there and experience it for yourself. We are learning a lot about what is required to actually be rugged-enough for Africa.[66]

But the expeditions also test the process of getting the BRCK online across countries and telecom providers (Figure 5-5) so that the team can streamline the process for users.

Figure 5-4. Checking antenna-enabled BRCK connectivity in rural Kenya using an Android monitoring app (image: Erik Hersman)

Figure 5-5. Documenting the process of buying a SIM card and data plan in Zambia (image: Mark Kamau)

Behavioral context

By “behavioral context,” we mean: time and place, the proximity or visibility of other people, animals, and things to the main participants, important physiological states of being... or any other tangible, sense-able dimensions of a given event or activity:

Time and place

What sorts of time-based rhythms might such a service need to learn and anticipate? A home security system might start by learning workday and weekend household routines. Over years of use, it could also adapt to predictable cycles of holiday plans and visits from family members. What events signal the arrival or departure of an inhabitant or guest?

Proximity and visibility

Who is allowed to access the home? When and how? Moreover, any kind of security service will have to consider privacy. What kinds of activities are usually visible to watchers? Which are typically private?

States of being

What kinds of vision, hearing, or other physiological capacities should we expect? For example, is it reasonable to expect users to remember numerical passcodes?

Identifying appropriate behavioral factors is often the first step in algorithmically modeling activities and responding appropriately. The difficulty lies in deciding which behavioral factors might accompany those activities, experimenting with how to sense those factors, and then figuring out how to translate sensor data into usable information. It’s not a small job. In Chapter 6, we’ll introduce ways to simulate sensing and responding to behavioral data in order to prototype devices such as fitness trackers or smart home gadgets.

Sociocultural

What expectations do people have for their own behavior? For other people? Who or what enforces them? And what happens when those expectations are violated? Sociocultural questions ask us to consider the reasons why we do some things...and not others. They ask us to consider how groups of people find similar meanings in objects and phenomena, and how those shared meanings might vary across different groups of people.

Research transforms the abstract and fuzzy concept of values into concrete, specific terms. What does safety or security in the home mean concretely to your audience? What specifically makes them feel safe and secure? How do they know they are not? Answering questions like these is the first step in articulating why your product idea is important (see Chapter 6 for more).

Business rules and governmental regulations may affect what kinds of services you can offer to users. What are the relevant laws and regulations, exactly? Earlier we mentioned Uber as an example of a profitable company dogged by regulatory concerns. What happens if your product stretches or breaks the law, and who judges compliance?

Most importantly, research into sociocultural context also helps anticipate controversy and discomfort. Take the case of Google Glass. It’s perfectly legal (in the United States) to record video in public places without first getting permission. Taking photographs of friends is socially acceptable—even encouraged. Yet head-mounting a small video camera, as Google Glass did, provoked controversy. Bars banned it (see Figure 5-6), and wearers encountered visible disapproval. Journalist Matt Honan, who wore Glass for a year, writes:

Even in less intimate situations, Glass is socially awkward. Again and again, I made people very uncomfortable. That made me very uncomfortable.[67]

Figure 5-6. Sign banning Google Glass (image: LoKan Sardari)

Experiences like Honan’s are why it can help to investigate sociocultural context by enacting scenarios and making prototypes—though hopefully less expensive prototypes than Glass (see Chapter 14 for more). Sociocultural expectations are so taken for granted that often, the best way to see them is when expectations of correct behavior are breached.[68]

Ecological

Ecological context, as the name might suggest, concerns what’s often called a product ecosystem: the networks of economic relationships that position an organization and its products in a larger world.

Designer Mike Kruzeniski, one of the creators of Microsoft’s groundbreaking Windows 7 design language, writes:

A good phone isn’t just the quality of the device in your hand, it’s the sum of the apps and services and accessories and cases and connected devices around it. If we wanted Windows Phone to be a great product, we would need to think of the product ecosystem as being a design problem as important as the product software.[69]

It’s hard enough simply designing a product in itself. So it’s easy to forget about cultivating what Kruzeniski calls the “the spaces adjacent to the product”: actors such as user groups and developer communities, and content contributors and distributors. Kruzeniski continues,

We needed to understand who would and wouldn’t be interested in developing apps, why developers would or wouldn’t want to build apps, what information was and wasn’t helpful for developers to design apps, and what kinds of tools developers were going to need to get started.

That’s why we do research into ecological context: to make sure that third parties will help make the product successful from the start. Thinking ecologically, you might ask yourself, how are potential users likely to hear about my home security service? If the original owner moves on, does the product/service move too, or does it remain with the house? See Figure 5-7.

Figure 5-7. Sample contextual factors in a home security service scenario in which the primary user is trying to open the front door remotely for a house guest

Research into ecological context can also inform graceful handling of product “end of life” activities such as reselling or recycling—the kind of activities important to responsible device design (see Chapter 15).

In the next section, we’ll discuss some ways to answer the topics we presented and questions we posed (Table 5-2).

Table 5-2. Starter questions for each aspect of context

|

Context |

Object of Study |

Questions |

|

Operational |

The physical settings of use |

What environmental conditions might the product encounter?What sorts of resources will likely be available to keep the product functioning? |

|

Behavioral |

Human activity and states of being |

What kinds of activities are important to you? What tangible attributes characterize those activities? |

|

Ecological |

Networks of organizational, legal, and economic relationships |

What actors and stakeholders are involved in creating and maintaining a product or service?What do those actors and stakeholders need to participate and cooperate? |

|

Sociocultural |

Shared ways of interpreting the world |

What expectations might actors and stakeholders have for themselves, others, and the product you are making?What happens when those expectations are violated?Who or what produces or enforces “appropriate” behavior for users, other actors, devices, etc.? |

Techniques: From Asking to Watching to Making

So how do you go about investigating people in context? This section will give you some techniques and tactics that we’ve found work especially well for questions specific to connected products. These techniques are great to use before you commit significant time and money to any single design direction.

Documenting how your audience deals with the situation or activity that interests you is always a good first step. Here, we’re going to focus on activities that will help you understand the context of use and what it means to your users, including spaces, time-based routines, interpersonal relationships, and sensory perceptions. The problem we’re trying to solve is that so many of the factors relevant to connected products aren’t easy for people to explain in words.

Words can fail to capture the context of potential use—the spaces, sights, sounds (or even smells!) that will matter to users and to the product. It can be hard for people to adequately describe in words the layout of their homes, or the sensation of hearing a fire alarm next door.

Moreover, psychological research tells us that human perception and memory are not objective. Research participants often volunteer stories of frightening—but rare—crises, but do not mention everyday frustrations that they have long since stopped noticing. Then there are the problems inherent in asking people what to design. Your potential users are expert in their own lives, but not necessarily in the practicalities of the design process or the capacities of emerging technologies.

Humans are also notoriously bad at predicting their own future actions. We may tell companies that we would like to have a refrigerator with a screen in the door...but when faced with the opportunity to buy one, we hesitate. Perhaps the hypothetical refrigerator was much more compelling than the reality. Or perhaps, when faced with competing demands on our wallets, an expensive new refrigerator turns out to be less important than a family member’s costly doctor bills or an overseas vacation.

Problems of knowledge, memory, and perception are problematic for all user-centered design projects, but especially so for connected products. Those everyday troubles can inspire a great new product—or they can doom your bright idea to irrelevance. That is, if your research participants aren’t network engineers, they probably can’t explain why their wireless networks are unreliable. They may not even know that their problems listening to streaming music have to do with an unreliable network in the first place.

Drawing on the work of Elizabeth Sanders, a designer and teacher, we can divide these factors up into three categories (Table 5-3):

Explainable

What people can articulate in words

Observable

Tangible events in the world that researchers can perceive with their senses

Tacit

Motivations, sensations, and other mental structures that are implicit in action but need to be made explicit in order to be used in design

It’s easy to learn about explainable factors: all you need to do is ask people! We can bring other tangible phenomena, such as technological infrastructures, to light with careful and sensitive observation. But aspirations, emotional associations, and the kind of cultural knowledge we usually take for granted are not so easily seen or heard. To use them to help use define a product, we’ll need to prompt or provoke research participants to go beyond what is easy to put into words (Table 5-3).

Table 5-3. Research techniques for connected products[a]

|

Participants... |

You Gather Information about what People... |

You Learn About Human Conditions that are... |

We Suggest... |

|

Answer questions |

SayThink |

Explainable |

Elicitation activities, such as map-making, prompt richer and more detailed conversation |

|

Behave normally |

DoUse |

Observable |

Field visits discover and document contexts of use, and provoke unexpected encounters |

|

Make and play |

KnowFeelDream |

Tacit |

Generative methods, such as co-design workshops, create artifacts in order to surface hard-to-articulate values, dreams, and assumptions |

|

[a] Adapted from E. Sanders and P.J. Stappers, Convivial Toolbox (Amsterdam: BIS Publishers, 2013). |

|||

Asking: Elicitation Tools

One of the best ways to go beyond what is easy to observe or articulate is by having participants document their lives themselves. We can then use that documentation in interviews to elicit richer and more detailed explanations:

§ Spatial maps help us associate everyday activities to places.

§ Timelines help people tell more detailed and more concrete stories about past events.

§ Diaries and usage logs help you understand what your users do, think, and feel when you’re not around.

Maps

Despite marketing promises, we can never—and should never—design for anytime, anywhere usage. Think about our problem of home security. There will probably be a mobile interface...but to monitor conditions we need components to place around the home. Those hardware components need to work with the actual spaces that potential users live in and move through—not the idealized ones we imagine.

Spatial maps help you understand what those homes and other places are like and the relationships their inhabitants have with them and with one another. Maps are convenient for interviewing because they are familiar. Who hasn’t drawn or read a map?

Spatial mapping starts with a question about a physical location. You ask someone to represent a place they know well (say, a home) and then gradually fill in the details that interest you. You might investigate operational context by asking for information about wireless networks and power outlets, or investigate needs and sociocultural context by asking emotional questions such as, “Where do you feel most safe in your home?” You can also ask people to draw movement in space, like a commute or a vacation route. What’s useful about these maps is the detail they offer about space and time. What’s less useful is that it’s hard to ask about nongeographic spaces, such as websites or applications.

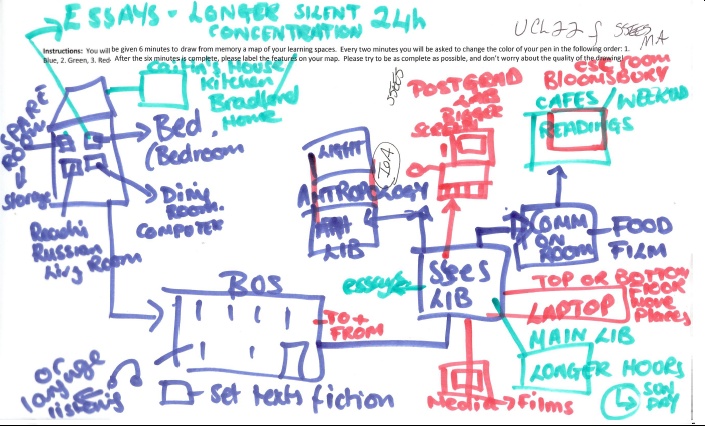

Cognitive mapping (Figure 5-8) starts with a question about an activity. You ask about “securing your house” or “learning to speak French.” Those kinds of maps limit themselves to geographic locations, but can include websites, devices, and books. These sorts of maps, anthropologist Donna Lanclos says, help you see “a network of spaces, with a relationship to each other.”[70] Cognitive maps often include buildings, technologies, and modes of transportation. However, they tend to be necessarily less informative about any given place.

Timelines

Making timelines (Figure 5-9) can help participants tell more detailed and concrete stories. Try this right now: write down what you did this morning from the moment you got up to when you left the house (if indeed you left the house). You’ll probably start remembering more events as you go, and you’ll need to reorder your list as more details come to you.

Figure 5-8. A cognitive map from a study of “post-digital learning landscapes” in London overlays types of work on places and devices; it includes sub-areas of a student’s house, her laptop, a commute on the bus, as well as multiple libraries and cafes (image: Donna Lanclos, University of North Carolina at Charlotte)

Figure 5-9. A timeline helps a participant in a study on energy use walk researchers through a typical day (image: Dan Lockton and Flora Bowden)

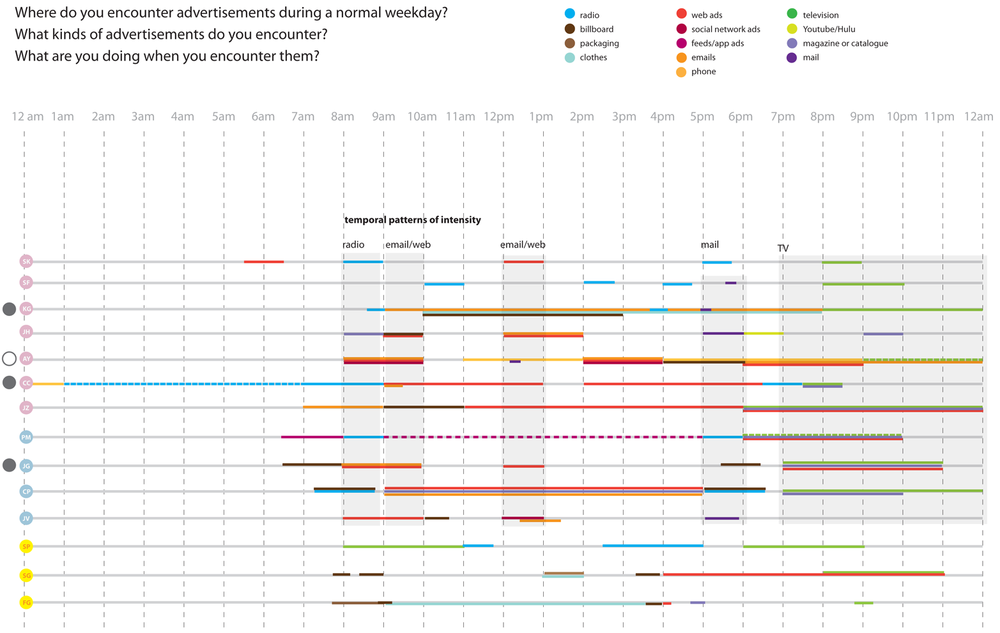

Perfect recollection is impossible, but asking participants to write down the steps they can remember on Post-it notes—then having them shuffle and add steps—will jog their memory. Timelines can spark explanations of cause and effect: “I got mad at my mom so when I left I forgot to lock the door.” Combining timelines into an overview (Figure 5-10) can surface shared sociocultural values and meanings—information that will help later when you are crafting value propositions.[71]

Figure 5-10. Combining individual timelines into a single overview surfaces common patterns of engagement with advertising (image: Elizabeth Goodman)

As a practical note, it’s a good idea to leave the question of what events begin or end the timeline up to the participant. Consider our home security project. You may assume that locking up starts when the key hits the lock. Your participants, however, might feel like the process actually starts with a panicked search through the house for perpetually misplaced keys. How to avoid or mitigate that panic might be the goal or need that sparks a new service or product.

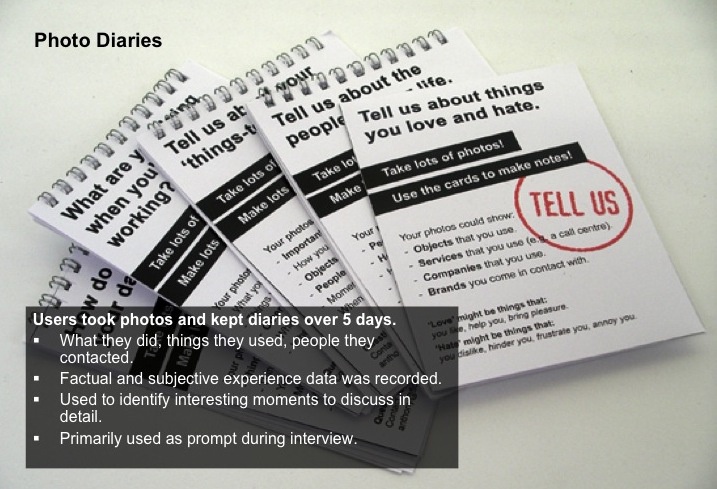

Diaries and usage logs

Diaries and/or activity logs (Figure 5-11) track activities and goals that happen over time (e.g., learning about a rash of neighborhood burglaries, following the news, changing one’s locks). They are just what you think: participant-completed records of what people do, think, and feel over time. You could have participants jot down notes on their improving fitness, for example, emailing you weekly updates. They could supplement what they write with photographs for greater detail. You can even give people deliberately open-ended tasks, such as Take a photo of something in your house that makes you anxious.

Figure 5-11. Diary studies are often in paper form so that participants can scribble and sketch on them more freely (image: Ant Mace)

Those weekly updates are less prone to memory bias than retrospective timelines, because they chronicle events as those events happen. When completed, diary entries can prompt interview questions about what participants felt and saw even months earlier.

If you have backend access to a digital product participants already use, you might even be able to get logs of their activity (getting their permission beforehand, of course). Or you can ask them to install an activity tracker app customized to your research questions that tracks the time and place of on-device actions. Those logs will necessarily not be as rich or evocative as diaries, but you can use post-study interviews to fill in the blanks. And they will definitely give you “ground truth” about what your participants get up to when you’re not around.

The Importance of Explanations

While a picture is said to convey more than a thousand words, pictures never tell the whole story. They cannot say “no”; they cannot give reasons; they cannot plan; and they cannot provide feedback on how they are being understood by others.

—KLAUS KRIPPENDORFFThe Semantic Turn: A New Foundation for Design, p. 139

It’s risky to interpret these artifacts on your own. They tend to be ambiguous, with lots of content that is personally meaningful to the participant and not particularly decipherable to a stranger. It’s easy to jump to wrong conclusions. What timelines, spatial maps, and diaries are for, then, is to elicit richer and more detailed verbal explanations from research participants.

We’ve highlighted three types of artifacts, but there are many other ways to elicit rich descriptions of current goals, needs, and activities. You can present participants with what Elizabeth Sanders calls a “trigger set” of evocative images from which they choose the most meaningful. You can have them smell, touch, and taste sample materials. You can give them illustrated scenarios of more-or-less futuristic future products to see how they respond. But the goal remains the same: to push participants to go beyond what is easily explainable to what is hard to articulate. It is the objects plus explanations that inform design strategy, not the objects alone.

Watching: Field Visits

The most effective way to identify people’s current goals, frustrations, and pleasures is to ask them. That’s logical enough. Interviewing skills such as asking thoughtful questions, being a careful listener, and analyzing the results are the foundation of all user research.

But you’ll want to go beyond verbal questions and answers. Particularly for connected products, user-centered design means taking what people say they want seriously but not always literally. On their own, interviews will only capture what people can verbalize. The first step is to move beyond the comfort of your own workplace into the places where potential users work, play, eat, and sleep.

Researchers call these trips out of the office “field visits.” If you’re designing security products and services for single-family homes, for example, that obviously means visiting the homes in question. Field visits typically serve two purposes:

§ To experience and document concrete “ground truth”

§ To engage with difficult-to-articulate cultural meanings

On such a field visit, you might

§ Tour an entire space (such as a private home).

§ Follow one person as they perform an activity (such as locking up before leaving on vacation).

§ Observe all the activities and tools in one specific place (such as the kitchen).

§ Trace the web of relationships and processes that make an object (such as a police report following a break-in) particularly meaningful to your audience.

§ Document hard-to-verbalize factors, such as the alarm code scrawled on a piece of paper or an outside door left propped open.

§ Take advantage of unexpected encounters (such as a home visit on which you meet previously unknown stakeholders, such as neighbors, mail carriers, or forgetful teenagers).

While in the field, your job is to:

Seek the unexpected

The exciting thing about research is that people’s lives are inevitably richer, stranger, and more complicated than you expect. To get the most out of a field visit, you need to seek out those surprising complications. One useful technique is the AEIOU schema, developed by business ethnographers at the Doblin Group in the 1990s.[72] In new environments, take 10 minutes to list all the activities, environments, interactions, objects, and users you can see. Your list will almost certainly give you some new questions to ask.

Be nosy

Being too shy to ask questions negates the whole point of the field visit. Who propped open the door? How did you feel about being robbed? Who pays for the new alarm system? Don’t assume that you understand what’s going on. Prepare a set of questions in advance, but be ready to keep probing until you get specific, concrete answers. Ask to open closed doors. If you care about health, for example, you’ll want to ask (politely!) to see where medicines are kept. Don’t assume that participants keep medicines where you would. Don’t assume that you and your participants define “medicine” similarly. It should go without saying, of course, never to express criticism or shock about what you discover.

Document your experience

Your memory is not enough. Take photographs, video, and notes of anything that strikes you as relevant and that you’ll need to share with other design stakeholders. For example, if you’re interested in cooking, then you might ask for a recipe to try yourself. Or you might try to buy some of the ingredients. The shopping trip can be a research exercise on its own, and the results can spark design.

Like so many parts of design, field visits seem straightforward enough, but in practice have enough hidden complications and fascinations to be a life’s work in itself. Field visits for design don’t have to be the sort of elaborate adventures documented in Figure 5-5. They can also be lightweight encounters, as shown in Figure 5-12.

Making: Generative Methods

Generative methods, such as co-design workshops, can get nondesigners directly involved in design. In early stages, generative methods help investigate everyday needs, dreams, anxieties, and habits. Later, with a product or service direction chosen, generative methods can help establish how touchpoints should concretely look, feel, and behave.

Figure 5-12. “Water me” signs sighted at a neighborhood-run garden inspire initial service proposals for collective urban resource management (image: Elizabeth Goodman)

Co-design workshops are semi-structured sessions in which professionals ask potential users to design new products and services by themselves, for themselves. Participants typically get kits of basic components they put together to make artifacts that tell stories or represent design concepts. Common outcomes include paper collages (Figure 5-13), or even LEGO models (Figure 5-14). Those artifacts, like objects in elicitation exercises, can then prompt rich, nuanced, concrete discussions about what people want for their lives.

Figure 5-13. Participants in a co-design exercise stick paper cards representing different types of functionality, such as a calendar and a keyboard, to a real car’s steering wheel and dashboard; note that the existing features are covered up to provide a blank canvas (image: SonicRim)

Figure 5-14. LEGOs help workshop participants imagine and act out telecom service scenarios (image: Andy Polaine)

Design consultancy Experientia uses generative methods to:[73]

§ Draw out intangible aspects of the product‘s environment, such as ethics, social norms, or cultural values—particularly ones that demand a choice among conflicting options

§ Generate resolutions for those conflicts, particularly processes over time that engage multiple stakeholders and touchpoints

§ Free participants from unnecessarily conservative or limited solutions, opening them up to imagine more diverse and more unpredictable future products and services

§ Anticipate how habits and behaviors might change with new products and services

Why use generative methods? The role of research is straightforward, if logistically sometimes complicated, in updating an existing product or designing a new entrant into a well-established product category. You can often draw a clear line from what you have observed to what you design—from observations, to insights, to principles, to definitions (see Chapter 6 for more). If you’re trying to invent an entirely new product category, or create an entirely new entry into an existing product category, user research gets more conceptually complicated. Along with information about existing practices, you need inspiration—grounded in everyday life—to invent something completely new.

Generative methods, especially co-design workshops, are one way to inspire fresh ideas that are still deeply grounded in people’s dreams and aspirations. They are also good ways to provoke sociocultural discussion and debate to inform prototyping.

Summary

Research doesn’t eliminate risk or creativity.

Successful products and services that require cooperation (or at least, not active rejection) depend on a web of relationships among direct actors, indirect stakeholders, and the contextual factors. While users are central, designers ignore nonusers and product context at their peril.

Connected products and services thrive when they acknowledge people’s diverse roles, expertise, and needs. Most obviously, there are immediate actors who make, use, repair, and dispose of the product. However, indirectly involved stakeholders also affect how the product works. Given such diversity, needs and goals are likely to be in conflict. Even if you can’t resolve any conflicts, your job is to anticipate them.

The success of connected products and services is also tightly coupled to contextual factors. Operational factors are those necessary for a product to function at all, which usually means appropriately engineering hardware for its environment but can also include the availability of replacements and parts. Behavioral factors refer to human physical activity and states of being. Ecological factors are the networks of organizational, legal, and economic relationships that support operation, such as third-party application developers. Finally, shared sociocultural factors inform how people make sense of the product—and how often and why they reject it.

Research should go well beyond asking people what they want. Enriched with diaries, maps, and timelines, ask activities elicit rich descriptions of actions, attitudes, and desires. Watch activities investigate nonverbal, contextual factors, often by sending teams on field visits. Generative make activities surface hard-to-articulate values, dreams, and assumptions by creating tangible artifacts.

Building a connected consumer product without upfront investigation will likely waste your time and money. However, we’re not advocating a traditional waterfall model, in which you do extensive research, build the product, and only then evaluate it. That’s likely to waste time and money, too. It’s simply impossible to anticipate every crucial question before you have a prototype.

Instead, we’re advocating what researcher Erika Hall calls a “just enough” approach. Do just enough investigation to answer the initial questions, then start quickly prototyping, then go back and use your prototypes to learn more about your audience and their world.

In the next chapters, we’ll discuss how to do that.

[62] However, lessening capacities may lead to compensation elsewhere. People with diminished vision often astonish fully sighted people with the sensitivity of their hearing. So, again, it’s wise to check one’s assumptions.

[63] Amazon.co.uk: Customer Reviews: BiC For Her Medium Ballpoint Pen (Box of 12) - Black. Retrieved from http://www.amazon.co.uk/product-reviews/B004FTGJUW.

[64] D. Jergler, “Uber, Lyft, Sidecar Toe-to-Toe with Insurers State-by-State.” Insurance Journal, June 27, 2014, http://bit.ly/1bD4YNl.

[65] For a short but compelling run-through of the complexities of operational context, see: D. Raffel, “It’s Often (a Lot) Harder Than It Locks,” January 8, 2015, http://bit.ly/1bD5jzq.

[66] P. Walton, “BRCK Expedition—A Dash South—Day 2,” BRCK, November 15, 2014, http://bit.ly/1bD5B9w.

[67] M. Honan, “I, Glasshole: My Year with Google Glass,” December 30, 2013, WIRED, http://www.wired.com/2013/12/glasshole/.

[68] This classic scholarly article on prototyping new products is worth reading: A. Crabtree, “Design in the Absence of Practice: Breaching Experiments,” Proceedings of the 5th Conference on Designing Interactive Systems: Processes, Practices, Methods, and Techniques (2004): 59–68.

[69] M. Kruzeniski, “Macrointeractions,” http://bit.ly/1bD6jUp.

[70] For more on how to interpret cognitive maps, see Lanclos, D. (2014, April 17) “Post-Digital Learning Landscapes.” Retrieved from http://www.donnalanclos.com/?p=10.

[71] For a very useful introduction to timelines, see Lockton, D. (2014, January 13) “A case study on inclusive design: ethnography and energy use.” Retrieved from http://bit.ly/1bD82sF.

[72] C. Wasson, “Ethnography in the Field of Design,” Human Organization 59:4 (2000).

[73] “Creating Together: Building Value with Participatory Design,” Experientia, http://bit.ly/1bD8Q0K.