Responsive Web Design, Part 2 (2015)

Counting Stars: Creativity Over Predictability

BY ANDREW CLARKE

People have called me a lot of things since I started working on the web. I try to forget some of them, but Jeffrey Zeldman — without whom most of us wouldn’t be working in this industry — once called me a “triple-talented bastard.” If you know how much I admire Jeffrey, you’ll also know how much that meant.

My background’s in fine art, rather than in graphic design or technology, and for the last sixteen years, I’ve worked as an art director and designer in a small creative studio called Stuff and Nonsense1. We spend our time designing for clients and for screens. As my friend Brendan Dawes once said (of himself), we “make fillings for rectangles.”

I’ve been designing for the web for most of my working life and so it feels like I know the medium pretty well. I’ve seen it change in ways that go far beyond what we see on screen. Beyond the emergence of the web standards technologies that Jeffrey Zeldman championed. Beyond the rise of mobile and the challenges of responsive web design.

At the same time, I’m watching our industry mature into something that’s very different from the almost joyfully naive, creative designer’s playground it was when I started. It’s now a place where designers rub shoulders with developers, researchers, scientists and user experience professionals.

Much of what has changed has been for the better; our combined knowledge and experience, plus the growing maturity of the ways we approach our work, have led, in many ways, to a better web. We’ve made a web that’s more accessible, flexible and responsive to users’ needs as well as to devices of all kinds.

Yet, as proud as I am with what we’ve achieved, I look at today’s web design with a growing sense of dissatisfaction, almost melancholy, because for everything we’ve gained, I fear there’s something that we’re losing.

While we focus our thoughts on processes, methods and mechanics for making the web more responsive, instead of on ideas, we’re losing the creative soul of our work. Soul that embodies individuality, personality, originality, and opinion. Soul that connects people with ideas. Soul that makes ideas memorable. Soul that makes what we do matter.

I fear that our designs lack energy and spontaneity because we’re thinking too early and then too often about the consequences of failure. I fear that we’re creating a web that’s full of safe designs because we’re driven by the need in some of us for predictability, reliability, and repeatability. We’re creating a web where design rarely dares to stray beyond the boundaries of established conventions.

The modern web demands to be responsive, and this is a creative challenge that we should relish. Multiscreen design represents an incredible opportunity to be creative, but so many of our designs follow same responsive formulas.

I don’t fear that all hope is lost, and I know that we can recover our ability to make memorable creative work for the web. I hope that this soulless period will pass like so many phases before it. I’m hopeful that we’re still capable of making work that, as Jony Ive said when he spoke about Steve Jobs in an interview for Time magazine, can “suck the air from the room.”2

Giving our work soul, making space and time for creativity, experimentation and, above all, ideas — that’s the subject of this chapter. I’ve taken its title from a quote from Mad Men’s Don Draper. It’s from an episode called ‘The Monolith’ in season seven, set in 1968. Don was told that “the IBM 360 (computer) can count more stars in a day than we can in a lifetime,” and he replied, “But what man laid on his back counting stars and thought about a number?”

The advertising world that Don inhabits is going to be the backdrop to this chapter because I believe that advertising is one place where we can look for the soul we’re missing. It’s also where we can learn as much about clear and concise communication, reduction and simplification as we can in what many now call user experience. I find advertising fascinating, but I know that not everyone shares my enthusiasm.

Our Responsive Designs Lack Soul

As someone who studied fine art, I believe that the job of solving our biggest problems should be for artists as well as for designers or engineers. I’m also as much of a sucker for an artist’s quote as I am for advertising. However, the artist Banksy doesn’t share my fondness for advertising, and he wrote:

“People are taking the piss out of you every day. They butt into your life, take a cheap shot at you and then disappear. They leer at you from tall buildings and make you feel small. They make flippant comments from buses that imply you’re not sexy enough and that all the fun is happening somewhere else. They are on TV making your girlfriend feel inadequate. They have access to the most sophisticated technology the world has ever seen and they bully you with it. They are The Advertisers and they are laughing at you.”3

There’s a common perception that advertising is an industry that routinely interrupts you when you least want interrupting, regularly attempts to sell you products you neither want nor need, and lies to you as it sells.

Writer and humorist Stephen Leacock once wrote:

“Advertising may be described as the science of arresting the human intelligence long enough to get money from it.”4

Ouch.

For some, “advertising” has become a dirty word.

So how can advertising — an industry that some might argue is outdated and irrelevant — teach us anything about the very different industry that we work in today? In his book Purple Cow5, Seth Godin wants us to:

“Stop advertising and start innovating […] because as consumers we’re too busy to pay attention to advertising.”

Yet he acknowledges that it’s probably impossible to read through a list of successful brands without either picturing one of their commercials, remembering their taglines or hearing their jingles ringing in our ears. Advertising has given us some of the strongest and most memorable creative work in decades, and the mark of great advertising is that it stays with us long after a campaign is over.

IT’S THE TASTE

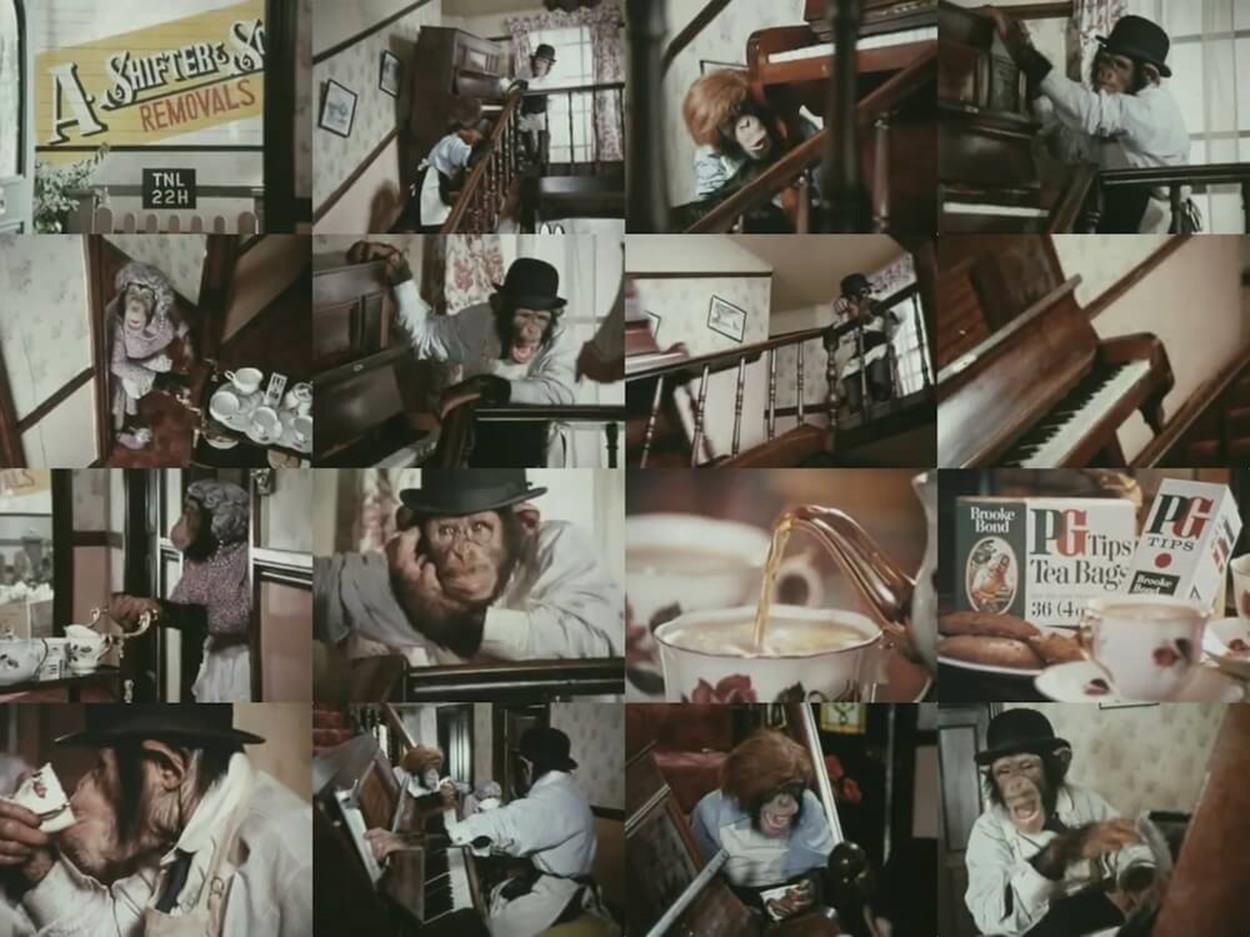

I guess that every generation remembers particular advertising. For me, it’s DDB’s chimpanzee campaign for PG Tips tea — “It’s the tea you can really taste.” The campaign began in 1956 with a black-and-white commercial and a voiceover by none other than Peter Sellers. The chimpanzees, often voiced by famous actors and comedians, parodied popular culture, politics, sports, and television for the next three decades. In 1971, “Avez vous un cuppa?” and “Cooey, Mister Shifter” became catchphrases that were as memorable as the campaign’s taglines, “There’s no other tea to beat PG” and “It’s the tea you can really taste.”

Mister Shifter, one of the most fondly remembered PG Tips commercials from the 1970s.

In the first two years of the chimpanzee campaign and off the back of its advertising, PG Tips went from fourth position to number one, and they maintained the top spot for the next 32 years, largely owing to their creative advertising. The campaign was more than clever copywriting and well-trained chimpanzees, and it succeeded because the combination of advertising and entertainment made the pleasure of watching the commercials synonymous with drinking PG Tips tea.

I could write an entire book about PG Tips and the chimpanzee advertising — and maybe one day I will — or about Leonard Rossiter and Joan Collins’ commercials for Cinzano. Please don’t get me started on Cadbury’s Smash instant mashed potato; or 1970s Texan bars, a toffee chocolate bar whose commercials featured a cartoon cowboy and possibly the best/worst cowboy tagline, “A man’s gotta chew what a man’s gotta chew.” Texan bars sure were “a mighty chew.”

Advertising agency Boase Massimi Pollitt and the Smash Martians helped to make Smash popular in 1974.

Today’s equivalent might be Wieden+Kennedy’s campaign for Old Spice’s “The Man Your Man Could Smell Like”: a series of commercials that cleverly targeted a male body wash product at female buyers who imagined their man smelling like the man in the commercials.

Wieden+Kennedy’s campaign for Old Spice’s “The Man Your Man Could Smell Like.”

THE SMELL OF A NEW CAR

Some people confuse advertising with misleading people about a product. However, successful and effective advertising, through a process of reduction, of removing messages that may cloud communication, aims to communicate and emphasize a truth about a product or a service or brand.

DDB’s famous campaign for the VW Beetle — the campaign that invented the modern advertising industry — wasn’t just memorable for its clever copywriting and distinctive art direction, but because it told the truth about Volkswagen’s product. The Beetle was noisy and small, but it was also well built and reliable. That was the truth. DDB’s advertising didn’t hide it and customers responded to that and the messages the advertising conveyed.

It still being the post-war period, consumers also responded to Volkswagen’s carefully constructed messages about the Beetle’s size and economy. A Beetle was a smart choice, and people aspired to feel smart about choosing one. In many ways the ads said, “this car is smart and individual, like you.”

Successful advertising always provokes an emotional response in us as consumers; and as Don Draper said in the first ever episode of Mad Men:

“Advertising is based on one thing: happiness. And you know what happiness is? Happiness is the smell of a new car. It’s freedom from fear. It’s a billboard on the side of the road that screams reassurance that whatever you are doing is okay. You are okay.”6

Old Spice’s “The Man Your Man Could Smell Like” commercials say nothing about the product itself apart from the fact that it doesn’t smell “lady-scented.” They also knowingly play on the fact that the advertisers and the audience know that the product won’t turn men into Isaiah Mustafa.

I would argue that Old Spice also told the truth about what it thinks many women consumers were thinking. They wanted their man to smell (and look) like Isaiah. Leonard Rossiter, Joan Collins and the Cinzano advertisers told the truth too. Just like Rossiter’s character, Cinzano was pretending to belong to a higher social class. For thirty years, PG Tips owned the truth about tea. Drinking a cup of PG Tips makes people happy.

All these campaigns conveyed messages about the products they advertised, and they did it with the charm, personality and wit that’s so vital in making creative work memorable.

While we can all probably point to a memorable commercial (PG Tips), poster campaign (United Colors of Benetton), or magazine ad (Levi’s 501 black,) can you point to as memorable a website from recent times?

I can think of many websites that are well presented, easy to use, triumphs of user experience and technically competent, but few that might be remembered for years to come. Why do you think this is? Why are so few websites memorable? Why do so few bare their souls? What could be the reasons?

Could the design processes we’ve come to rely on, particularly in relation to responsive design, have hindered our creativity? Our modern web design magazines are full of advice about process, techniques and tools, but little about creativity, about humanity, or about ideas.

Can our emphasis on human–computer interaction mean that we forget the importance of human–human communication?

Does our reliance on research and testing mean that we’re simply delegating decision-making and abdicating responsibility for our designs?

Has our current preoccupation with user experience methodologies meant that we’re less willing to take risks?

Have we become so fixated with designing digital products that we’ve forgotten that the web is a medium for communication outside of applications? Much of what I read today amplifies the voices of data-driven design over ideas-led design.

Irene Au is the former head of design at Google and Yahoo, and she explains user experience like this:

“User experience design is a multidisciplinary field. A well-designed product must be visually appealing and simple, and easy to understand, learn, and use. Creating a well-designed product is an endeavor that requires technical skills — an understanding of computer science, human computer interaction, and visual perception and cognition — and tremendous creativity.”7

I believe that all these factors have combined to create an environment that produces work that, while aesthetically appealing, well-considered and technically accomplished, still somehow lacks the emotional appeal that’s as important as functional abilities.

LETTERS TO A JUNIOR DESIGNER

In April 2014, A List Apart magazine published a “Letter to a Junior Designer8” by columnist, product designer at Twitter, and author of Undercover User Experience Design Cennydd Bowles. In it he made his case for young or new designers to “slow down,” “think it through,” and “temper their passion.”

“Slow down,” he wrote. “You pluck an idea from the branch and throw it onto the plate before it has time to ripen.” He went on:

“Perhaps your teachers exalted The Idea as the gem of creative work; taught you The Idea is the hard part. I disagree. Ideas aren’t to be trusted. They need to be wrung dry, ripped apart.”

When I read his words and I thought about the junior designers Cennydd was writing to, I imagined design as it might be in a dystopian future where there’s little time for an idea to blossom before it’s crushed under the boot of user experience.

When Cennydd wrote:

“In time, the distinction between idea and iteration will blur. Eventually, the two become one.”

I heard the words of George Orwell:

“Power is in tearing human minds to pieces and putting them together again in new shapes of your own choosing.”9

Like Winston Smith’s character at the end of 1984, I imagined the junior designers Cennydd was writing to as disheartened and demoralized, yet somehow accepting their fate.

I felt compelled to respond, so I wrote “A Different Letter to a Junior Designer10.” One that I hoped would inspire rather than depress those same junior designers.

I wanted to tell them that there can be a future where their energy and enthusiasm will make a difference. That they must never forget that it’s ideas that matter most, that without them there would be nothing. That you can’t turn a poor idea into a brilliant one by iterating. That instead of having fewer ideas, we must make more.

“Don’t slow down,” as Cennydd suggested. “Speed up.” I wrote:

“Your mind is a muscle, just like any other: you need to use it to keep it in top condition. To keep making ideas happen, make more of them, more often. Feed your mind with inspiration wherever you can find it. Exercise it with play. Make idea after idea until making them becomes a reflex.”

The truth is, we don’t always need to think things through, at least not right away. We can’t ever predict the path our ideas will take. We can’t know the restrictions they’ll face nor the limitations that will be put on them. My advice is not to try.

Too often, I see brilliant ideas extinguished because people think about practicalities too early. How will this be built? How can we make it responsive? How will someone use it? These are important questions, at the right time. Naturally, some ideas will fade, but others will dazzle. Before we pinch out the flickering flame of a new idea, let it burn brightly for a while longer, unhindered by practicalities.

CREATIVE HIJINKS

A tension between approaches to design — between data- and implementation-led digital product design and ideas-driven web design, as starkly illustrated by Cennydd’s and my respective letters to junior designers — certainly isn’t a new phenomenon.

Towards the end of the 1960s, technology had begun to creep into advertising and in 1968, Mad Men’s Sterling Cooper & Partners agency installed their first computer, the room-filling, low-humming IBM System/360 that I mentioned earlier. Of course, this being Mad Men, nothing’s ever as straightforward as installing a computer.

Practically, entering the future means installing that computer on the site of the agency’s creative lounge, a space where art directors and copywriters meet to collaborate. Without a central space to share, the creatives are forced back into their separate offices, afraid that the computer will replace them. Don Draper’s only half joking when he asks the engineer who’s installing the computer: “Who’s winning? Who’s replacing more humans?”

New partner Jim Cutler’s vision for SC&P is in stark contrast to Don’s when he says:

“I know what this company should look like. Computer services.”

and:

“This agency is too dependent on creative personalities. We need to tell our clients we’re thinking about the future, not creative hijinks.”11

It might seem at first that Cennydd’s data-led digital product design and my ideas-driven web design are at opposite ends of a spectrum of design styles, but ideas aren’t at odds with user experience — they are a fundamental part of it. The mixing of the two is a wonderful creative challenge. There is common ground that gives me hope. Cennydd wrote in his letter to a junior designer:

“We’d love to believe design speaks for itself, but a large part of the job is helping others hear its voice.”

I agree, because when our work has a voice, it means that it stands for something.

ALLERGIC TO RESEARCH

Sir John Hegarty is a co-founder of advertising agency Bartle Bogle Hegarty, BBH. He’s written about advertising in his book Hegarty On Advertising: Turning Intelligence Into Magic and most recently about creativity in There are No Rules, and I can’t recommend both books highly enough. In Turning Intelligence Into Magic12, Hegarty wrote:

“It’s essential […] for a creative company to have a point of view and a philosophical foundation for their work.”

And a point of view is an essential part of design. Like the best art, the best design must stand for something. We should ask ourselves: What does my work, or my company, stand for? What are our principles? We must stand behind our work because we believe in it, not because our point of view has evolved through iteration, been validated by testing or driven by research.

David Ogilvy, whom the New York Times once called “The Father of Advertising,” was fanatical about George Gallup’s research work and the company Gallup founded in 1935 after leaving the Young and Rubicam advertising agency where he’d been director of research. Ogilvy wrote in his book Ogilvy On Advertising13:

“For 35 years I have continued in the [research] course charted by Gallup collecting factors the way other men collect pictures and postage stamps. If you choose to ignore these factors, good luck to you. A blind pig can sometimes find truffles, but it helps to know that they are found in oak forests.”

I disagree with Ogilvy. I believe that research should inform creative decisions, not direct them, and that no amount of research is a substitute for a good idea. At least not on its own. I guess that by disagreeing, I’m simply proving Ogilvy correct when he wrote in his book that “Creative people are stubbornly allergic to research.”

I worry, though, that as an industry we’ve become too heavily focused on conversations about research-driven, data-led design and subsequent implementation issues including performance and responsiveness. Perhaps this is because our industry’s press writes more about apps than it does about websites. Just as our press needs to find a better balance, so do we. I’m happy that Cennydd and I agree. In a follow-up to our letters, Cennydd wrote:

“As with any discussion about beliefs, the danger lies in the extremes. It’s possible to become so invested in a data-only or idea-only approach that you become blind to the value of fitting your approach to the context.”14

That’s true: we should temper our use of data with hunches and vice versa, because, as Cennydd went on:

“Product design that’s driven entirely by data is horrible. It leads us down a familiar path: the 41 shades of blue, the death by 1000 cuts, the button whose only purpose is to make a metric arc upward. It’s soul-destroying for a designer.”

We should acknowledge that data-informed design “reduces risk, and encourages confidence and accountability.” But at the same time we must understand that the creative process is, by definition, unpredictable and so we should embrace risk because we may never know what direction an idea will take us.