Responsive Web Design, Part 2 (2015)

Counting Stars: Creativity Over Predictability

Common Ground In Creative Teams

David Ogilvy was a strong advocate of long copy — sometimes very long — and he wrote ads that contained more words than you’ll find in many of today’s pocket-guide-style books about web design. Ogilvy wrote in his own Ogilvy On Advertising book:

“All my experience says that for many great products, long copy sells more than short.”

He cited one successful advertisement for Merrill Lynch in the New York Times that ran to 6,450 words. His Ogilvy and Mather agency made an ad for US Trust that contained 4,500 words. Another for World Wildlife Fund: 3,232 words. Ogilvy wrote:

“Advertisements with long copy convey the impression that you have something important to say, whether people read the copy or not.”

This runs counter to what many people would expect, particularly on websites, but Ogilvy was clearly from a school of advertising that believed that “the more facts you tell, the more you sell.”24 We might flinch at the thought of reading thousands of words in an advertisement today.

IT’S UGLY BUT IT GETS YOU THERE

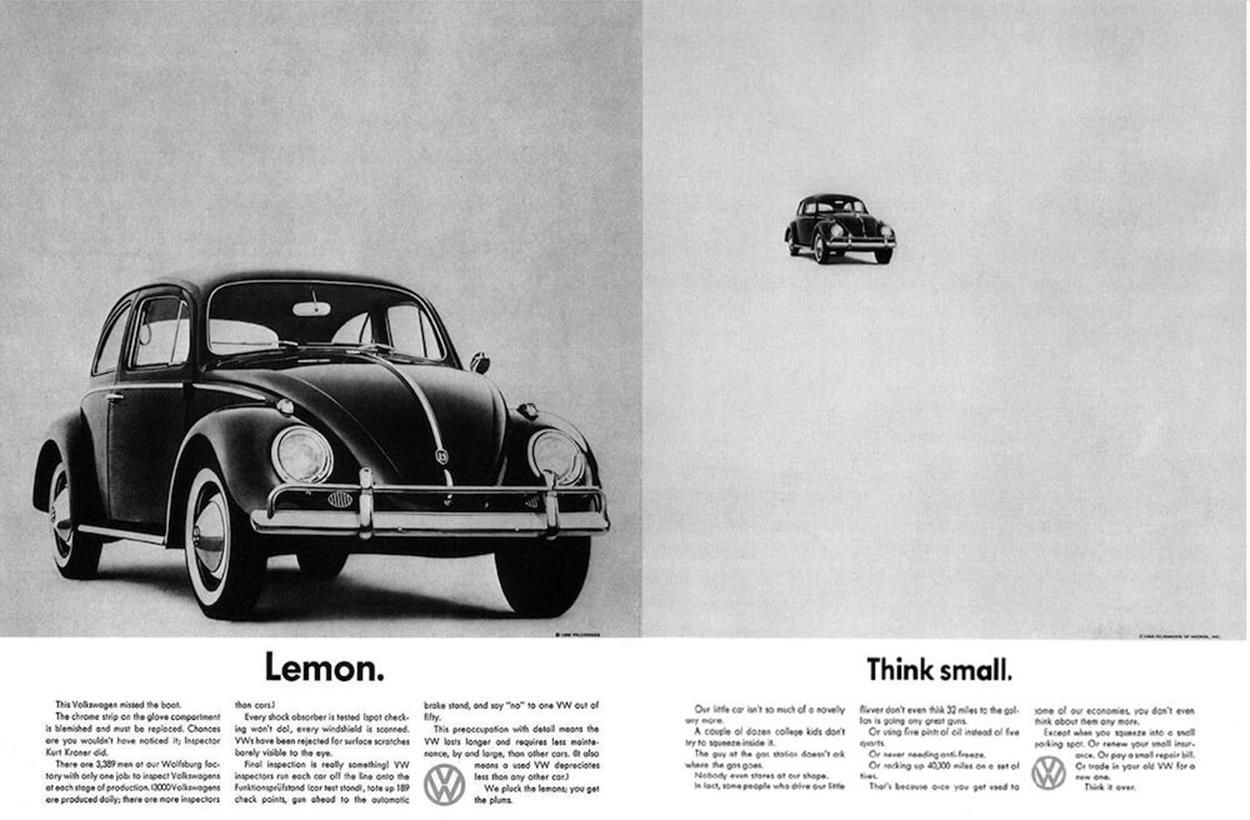

Things changed in the late 1950s with Doyle Dane Bernbach’s widely cited “Think Small” and “Lemon” ads for Volkswagen of America, art-directed by Helmut Krone.

Doyle Dane Bernbach’s iconic work for Volkswagen of America is widely thought to have changed the advertising industry.

Here’s the body copy from “Think Small” written by Julian Koenig. Count how many selling points there are:

“Think small.

Our little car isn’t so much of a novelty any more. A couple of dozen college kids don’t try to squeeze inside it. The guy at the gas station doesn’t ask where the gas goes.Nobody even stares at our shape. In fact, some people who drive our little flivver don’t think 32 miles to the gallon is going great guns.Or using five pints of oil instead of five quarts.Or never needing anti-freeze. Or racking up 40,000 miles on a set of tires.That’s because once you get used to some of our economies, you don’t even think about them any more.Except when you squeeze into a small parking spot. Or renew your small insurance. Or pay a small repair bill. Or trade in your old VW for a new one. Think it over.”

139 words, eight selling points, not including probably the most important fact that the VW is free of college kids. Having had a kid at college, I can tell you how important that is.

From “Think Small” and “Lemon” onwards, the Volkswagen of America ads were consistent in their format: a large space for a photograph of the car, and a smaller one for everything else: tagline, body copy, and logo. The car didn’t always fill the space but was mostly shot against a plain background.

In 1969, they ran “It’s ugly but it gets you there.” That tagline, a photo of the Apollo 11 lunar module and a VW logo. I love 1962’s “And if you run out of gas, it’s easy to push.” The cleverness of that tagline and the body copy that ran under it:

“It’s a little surprising that VW owners don’t run out of gas more often. A figure like 32 miles to the gallon can make you a little hazy about when you last filled up.”

And more classic taglines:

“It makes your house look bigger.”

“The only water a Volkswagen needs is the water you wash it with.”

“After we paint the car we paint the paint.”

WE’RE №2, SO WE TRY HARDER

Bill Bernbach is not only credited with changing the style of advertising with DDB’s work for Volkswagen of America; he’s also credited with changing the way that copywriters and art directors worked on ads.

Before Bernbach, copywriters and art directors worked separately. Copywriters wrote the copy for an ad and sent it to an art director, who worked in another department, to add visuals. If this were Mad Men, that would mean Peggy Olson and Stan Rizzo work not just in separate offices but on different floors.

Bernbach had a theory: if art directors and copywriters worked together in a creative team, they would produce better advertising. He was proved right: out of these creative pairings, his agency produced some of the most iconic work of that period including not just Volkswagen of America, but also the classic “We’re №2, So We Try Harder” campaign for Avis rental cars.

Throughout the decades that followed Bernbach, creative teams of art directors and copywriters remained at the center of advertising. But a copywriter’s role changed and while imaginative headlines remained important, long copy became unfashionable, and the emphasis in advertising shifted more towards the visual and away from long passages of written copy. Copywriting focused on reduction and writing a tagline meant using as few words as possible.

MAKE COPYWRITING A PRIORITY

Today I think that copywriting matters more than it has at any time since Ogilvy’s era. On the web, we need copy that’s effective from 140 characters in a tweet, through a Facebook message, to an email newsletter and up to long-form website content.

Designers need to either write copy themselves or work very closely with a copywriter throughout all stages of a project. Clients should also make copywriting a priority and make provision for it, not only within their budgets but from the beginning of any project. Copy should never be an afterthought, something to add to predesigned page templates, because thinking about words is a catalyst for new ideas and can help develop better strategies.

Designers must take greater responsibility for copy, too. For years, we’ve complained about waiting for clients to provide us with content. Then we complained some more about the quality of what we eventually received. Why are we surprised by a lack of quality and by a client’s lack of writing skills? After all, a client may know their business inside-out or their product better than anyone, but that doesn’t necessarily give them the skills to write. Why do we expect someone who works in finance, manufacturing, or services to be good at writing advertising copy, for the web or anywhere else?

Communicating through written copy is as creative a task as creating color palettes, designing with type and working with layout. At my agency, we think of copy as being at the center of everything we design. We spend an increasing amount of time editing existing and writing original copy for our clients.

THINKING STRATEGICALLY

Working with people to write copy helps us develop deeper relationships with our clients than when we work on design alone. We get to know our clients better and their businesses in much more detail. That’s why we know more today about Drupal development, health and safety inspections, and pension planning than we did a year ago.

Copywriting is now as integral to our business as creative design and accomplished technical development. Of course, copywriting means more than being creative with words. When we write, we’re thinking strategically. We’re balancing a user’s goals with those of our client, so in many ways a copywriter is as much a strategist as anyone who works in user experience.

We consider how headlines define a content’s hierarchy and create structure within body copy, just as information architecture would. We think about how those same headings can be used to convey the meaning of each section of content, making a page easier to scan and understand without the user needing to read every word. For us, this is as much part of a user experience design process as devising personas and making wireframes.

All this makes me wonder whether “copywriter” is now an outdated term. But what can we replace it with to better explain the work that goes along with writing words? “Creative writer”? Probably not, because what writing isn’t creative? What about “writer”? That’s simple, and it gets straight to the point.

CREATIVE DIRECTION, ART DIRECTION, AND DESIGN

An art director’s role has also changed as new media and technologies have emerged. Just as it did when the advertising industry moved from print-based work to embrace television, we’ve seen a similar change demanded by the web and everything that’s associated with it.

One of the biggest issues facing art direction on the web is that so few people understand what it is and how it differs from design. Ask a web designer what they think of when they hear the words “art direction” and many will mention the trend for individually designed articles and blog entries made popular by Jason Santa Maria, Trent Walton, and Gregory Wood.

There are overlaps between creative direction, art direction, and design, so it shouldn’t come as much of a surprise when people use those terms interchangeably.

Of course designers can, and sometimes do, art-direct and art directors can design, but the role of designer is different from the role of art director. Art directors provide a concept and designers provide ideas and expertise to implement that concept.

Art director and designer at Philadelphia-based design studio SuperFriendly, Dan Mall does a great job of explaining the difference between art direction and design. He wrote:

“Art Direction [is] the visceral resonance of how a piece of work feels. In other words, what you feel in your gut when you look at a website, app, or any piece of design work.”25

Whereas he explained good design being “measured in precision.”

“Design is the technical execution of that connection. Do these colors match? Is the line-length comfortable for long periods of reading? Is this photo in focus? Does the typographic hierarchy work? Is this composition balanced?”26

FIXATED WITH PROBLEM-SOLVING

I studied fine art and not graphic design in any form. I’m largely self-taught, so I’ve always been slightly uncomfortable describing myself as a designer. I almost feel that it’s disrespectful to people who can legitimately call themselves designers.

These days, we employ designers who are far more technically accomplished than I am, so my role has developed into one where I’m more regularly working on the atmosphere in a project and not on its look. I’m more often concerned with how our work conveys our clients’ messages than I am with the implementation details of that work.

I know that many people treat “look” and “feel” as synonyms and use them interchangeably. Yet the two are distinct attributes. We need the skills of a designer when we create a look, but the feel requires the skills of an art director who can ensure that those messages aren’t lost through design.

Phil Coffman is an art director at digital strategy agency Springbox. He said:

“Design is about problem-solving, whether you are a designer or an art director. The two roles differ in that the designer is more concerned with execution, while the art director is concerned with the strategy behind that execution.”27

On the web, we’ve become so fixated with problem-solving and execution that our work has lost the creative soul I spoke of at the start of this chapter. Soul that embodies individuality, personality, originality and opinion. Soul that connects people with ideas. Soul that makes an idea memorable. Soul that makes what we do matter.

As Dan Mall explained:

“Art direction brings clarity and definition to our work; it helps our work convey a specific message to a particular group of people. Art direction combines art and design to evoke a cultural and emotional reaction. […] Without art direction, we’re left with dry, sterile experiences that are easily forgotten.”

Even though we seem obsessed by designing experiences, much of the work I see on the web today is exactly as Dan describes, dry and sterile. I partly blame lack of art direction for its lack of soul.

DECORATING INSTEAD OF COMMUNICATING

Irene Au’s list of UX skills includes only:

•User research

•Interaction and product design

•Visual design

•Prototyper

•Web developer

•Front end developer

Where is anything approaching the role of art director in her list of UX talent?

Why is art direction on the web so rare? Jeffrey Zeldman himself comes from a New York advertising background, and in 2003 Zeldman wrote:

“On the web, art direction is rare, partly because much of the work is about guiding users rather than telegraphing concepts, but also because few design schools teach art direction.”28

He went on:

“[T]alented stylists continually enrich the world’s visual vocabulary. The bad news is, we are decorating instead of communicating.”

Stylists. Decorating. Just like the “visual adornment” Irene Au described 11 years later.

I think art director and designer Stephen Hay summed up the importance of art direction for us when he wrote:

“Good design is pretty, but good design based on a solid concept will help make your sites much more effective and memorable, especially when compared to the competition.”29