Switching to the Mac: The Missing Manual, Mavericks Edition (2014)

Part IV. Putting Down Roots

Chapter 15. Networking, File Sharing & Screen Sharing

Networks are awesome. Once you’ve got a home or office network, you can copy files from one machine to another—even between Windows PCs and Macs—just as you’d drag files between folders on your own Mac. You can send little messages to other people’s screens. Everyone on the network can consult the same database or calendar, or listen to the same iTunes music collection. You can play games over the network. You can share a single printer or cable modem among all the Macs in the office. You can connect to the network from wherever you are in the world, using the Internet as the world’s longest extension cord back to your office.

In OS X, you can even do screen sharing, which means that you, the wise computer whiz, can see what’s on the screen of your pathetic, floundering relative or buddy elsewhere on the network. You can seize control of the other Mac’s mouse and keyboard. You can troubleshoot, fiddle with settings, and so on. It’s the next best thing to being there—often, a lot better than being there.

NOTE

This chapter concerns itself with local networking—setting up a network in your home or small office. But don’t miss its sibling, Chapter 10, which is about hooking up to the somewhat larger network called the Internet.

Wiring the Network

Most people connect their computers using one of two connection systems: Ethernet or WiFi.

NOTE

Until OS X Lion came along, Apple had its own name for WiFi: AirPort. That’s what it said in System Preferences→Network, for example, and that’s what the ![]() menulet was called.

menulet was called.

AirPort was a lot cleverer, wordplay-wise, than the meaningless “WiFi.” Unfortunately, not many people realized that AirPort was the same thing as what the rest of the world called WiFi. So at least in the onscreen references, these days, Apple gives AirPort a new name: WiFi.

Ethernet Networks

Every Mac (except the MacBook Air) and every network-ready laser printer has an Ethernet jack (Figure 15-1). If you connect all the Macs and Ethernet printers in your small office to a central Ethernet hub, switch, or router—a compact, inexpensive box with jacks for five, 10, or even more computers and printers—you’ve got yourself a very fast, very reliable network. (Most people wind up hiding the hub in a closet and running the wiring either along the edges of the room or inside the walls.) You can buy Ethernet cables, plus the hub, at any computer store or, less expensively, from an Internet-based mail-order house; none of this stuff is Mac-specific.

TIP

If you want to connect only two Macs—say, your laptop and your desktop machine—you don’t need an Ethernet hub. Instead, you just need a standard Ethernet cable. Run it directly between the Ethernet jacks of the two computers. (You don’t need a special crossover Ethernet cable, as you did with Macs of old.) Then connect the Macs as described in the box on Networking Without the Network.

Or don’t use Ethernet at all; just use a FireWire cable or a person-to-person WiFi network.

Figure 15-1. Every Mac except the Air has a built-in Ethernet jack (left). It looks like an overweight telephone jack. It connects to an Ethernet router or hub (right) via an Ethernet cable (also known as Cat 5 or Cat 6), which ends in what looks like an overweight telephone-wire plug (also known as an RJ-45 connector).

Ethernet is the best networking system for many offices. It’s fast, easy, and cheap.

WiFi Networks

WiFi, known to the geeks as 802.11 and to Apple fans as AirPort, means wireless networking. It’s the technology that lets laptops get online at high speed in any WiFi hotspot. Hotspots are everywhere these days: in homes, offices, coffee shops, hotels, airports, and thousands of other places.

TIP

At www.jiwire.com, you can type in an address or a city and learn exactly where to find the closest WiFi hotspots.

When you’re in a WiFi hotspot, your Mac has a very fast connection to the Internet, as though it’s connected to a cable modem or DSL.

WiFi circuitry comes preinstalled in every new Mac. This circuitry lets your machine connect to your network and the Internet without any wires at all. You just have to be within about 150 feet of a base station or (as Windows people call it) access point, which must in turn be physically connected to a network and Internet connection.

If you think about it, WiFi is a lot like a cordless phone, where the base station is, well, the base station, and the Mac is the handset.

The base station can take any of these forms:

§ AirPort base station. Apple’s sleek, white, squarish base stations ($100 to $180) permit as many as 50 computers to connect simultaneously.

UP TO SPEED: AIRPORT A, B, G, AND N: REGULAR OR SUPERSIZED?

In the short history of wireless networking, WiFi gear has come in several variants, bearing the absurdly user-hostile names 802.11b, 802.11g, 802.11a, 802.11n, and so on.

The difference involves the technical specs of the wireless signal. Original AirPort uses the 802.11b standard; AirPort Extreme uses 802.11g; the current AirPort cards and base stations use 802.11n.

So what’s the difference? Equipment bearing the “b” label transfers data through the air at up to 11 megabits per second; the “g” system is almost five times as fast (54 megabits a second); and “n” is supposed to be four times as fast as that.

(Traditionally, geeks measure network speeds in megabits, not megabytes. If you’re more familiar with megabytes, though, here’s a translation: The older AirPort gear has a top speed of 1.4 megabytes per second, versus more than 6 megabytes per second for the AirPort Extreme stuff.)

(Oh, and while we’re using parentheses here: The only place you’ll get the quoted speeds out of this gear is on the moon. Here on earth, signal strength is affected by pesky things like air, furniture, walls, floors, wiring, phone interference, and antenna angles. Speed and signal strength diminish proportionally as you move away from the base station.)

Now, each successive version of the WiFi base station/laptop circuitry standard is backward-compatible. For example, you can buy a new, 802.11n base station, and still connect to it from your ancient 802.11g PowerBook. You won’t get any greater speed, of course—that would require a laptop with an 802.11n transmitter—but you’ll enjoy the greater range in your house.

It’s important to understand, though, that even the most expensive, top-tier cable modem or DSL service delivers Internet information at only about half a megabyte per second. The bottleneck is the Internet connection, not your network. Don’t buy newer AirPort gear thinking that you’re going to speed up your email and Web activity.

Instead, the speed boost you get with AirPort Extreme is useful only for transferring files between computers and gadgets on your own network (like the bandwidth-hungry Apple TV)—and playing networkable games.

And one more note: All WiFi gear works together, no matter what kind of computer you have. There’s no such thing as a “Windows” wireless network or a “Macintosh” wireless network. Macs can use non-Apple base stations, Windows PCs can use AirPort base stations, and so on.

The less expensive one, the AirPort Express, is so small it looks like a little white power adapter. It also has a USB jack so you can share a USB printer on the network. It can serve up to 10 computers at once.

§ A Time Capsule. This Apple gizmo is exactly the same as the AirPort base station, except that it also contains a huge hard drive so that it can back up your Macs automatically over the wired or wireless network.

§ A wireless broadband router. Linksys, Belkin, and lots of other companies make less expensive WiFi base stations. You can plug the base station into an Ethernet router or hub, thus permitting 10 or 20 wireless-equipped computers, including Macs, to join an existing Ethernet network without wiring. (With all due non-fanboyism, however, Apple’s base stations and software are more polished and satisfying to use.)

TIP

It’s perfectly possible to plug a WiFi base station into a regular router, too, to accommodate both wired and wireless computers.

§ Another Mac. Your Mac can also impersonate an AirPort base station. In effect, the Mac becomes a software-based base station, and you save yourself the cost of a separate physical base station.

§ A modem. A few, proud people still get online by dialing via modem, which is built into some old AirPort base station models. The base station is plugged into a phone jack. Wireless Macs in the house can get online by triggering the base station to dial by remote control.

TIP

If you connect through a modern router or AirPort base station, you already have a great firewall protecting you. You don’t have to turn on OS X’s firewall.

GEM IN THE ROUGH: NETWORKING WITHOUT THE NETWORK

In a pinch, you can connect two Macs without any real network at all. You can create an Ethernet connection without a hub or a router—or an AirPort connection without a WiFi base station.

To set up the wired connection, just run a standard Ethernet cable between the Ethernet jacks of the two Macs. (You don’t need to use an Ethernet crossover cable, as you did in days of old.)

To set up a wireless connection, from your ![]() menulet, choose Create Network. Make up a name and password for your little private network, and then click OK. On the second Mac, choose

menulet, choose Create Network. Make up a name and password for your little private network, and then click OK. On the second Mac, choose ![]() →Join Network, enter the same private network name, and then click Join.

→Join Network, enter the same private network name, and then click Join.

At this point, your two Macs belong to the same ad hoc micro-network. If you’ve shared some folders on the first Mac, its name (like “Casey’s iMac”) now appears in the Sidebar of the second Mac. Click it to see what’s on it. From here, proceed exactly as described on Accessing Shared Files.

You use the AirPort Utility (in your Applications→Utilities folder) to set up your base station; if you have a typical cable modem or DSL, the setup practically takes care of itself.

Whether you’ve set up your own wireless network or want to hop onto somebody else’s, Chapter 10 has the full scoop on joining WiFi networks.

Cell Networks

If you have an iPhone or a similar cellphone, you may be able to get your Mac online even when you’re hundreds of miles from the nearest Ethernet jack or WiFi hotspot. Thanks to tethering, your phone can act as an Internet antenna for your laptop, relying on the slow, expensive, but almost ubiquitous cellular network for its connection. Details are on Tethering.

FireWire Networks

Apple is busily phasing out the convenient, fast FireWire jacks on its Macs. But if you have two FireWire-equipped Macs, you can create a blazing-fast connection between them with nothing more than a FireWire cable. Details are in the free downloadable appendix to this chapter called “FireWire Networking.” It’s available on this book’s “Missing CD” page at www.missingmanuals.com.

File Sharing: Three Ways

When you’re done wiring (or not wiring, as the case may be), your network is ready. Your Mac should “see” any Ethernet or shared USB printers, in readiness to print (Chapter 9). You can now play network games or use a network calendar. And you can now turn on File Sharing, one of the most useful features of all.

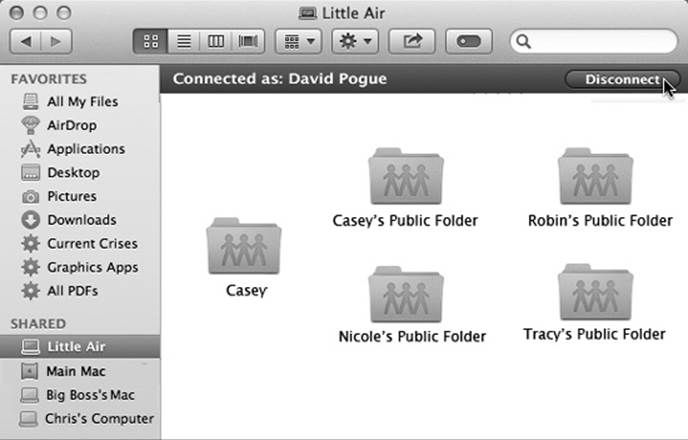

In File Sharing, you can drag files back and forth between different Macs (or even Windows PCs) on the network, exactly as though the other computer’s folder or disk is a hard drive connected to your own machine. You can see the idea in Figure 15-2.

The thing is, it’s not easy being Apple. You have to write one operating system that’s supposed to please everyone, from the self-employed first-time newbie to the network administrator for NASA. You have to design a networking system simple enough for the laptop owner who just wants to copy things to a desktop Mac when returning from a trip, yet secure and flexible enough for the network designer at a large corporation.

Clearly, different people have different attitudes toward the need for security and flexibility.

That’s why OS X offers three ways to share files, striking three different positions along the Simplicity-to-Flexibility Spectrum:

§ The easiest way: AirDrop. This feature is dreamy—if there are other people in your house or office who have wireless Macs running Lion or later. Imagine this: You open the AirDrop folder, where you see everybody else’s icons. To give someone a file, you drop its icon on that person’s face. Done.

§ What used to be the easiest way: the Public folder. Every account holder has a Public folder. It’s free for anyone else on the network to access. Like a grocery store bulletin board, there’s no password required. Super-convenient, super-easy.

There’s only one downside, and you may not care about it: You have to move or copy files into the Public folder before anyone else can see them. Depending on how many files you want to share, this can get tedious, disrupt your standard organizational structure, and eat up disk space.

§ The flexible way: any folder. You can also make any file, folder, or disk available for inspection by other people on the network. This method means that you don’t have to move files into the Public folder, for starters. It also gives you elaborate control over who is allowed to do what to your files. You might want to permit your company’s executives to see and edit your documents, but allow the peons in Accounting just to see them. And Andy, that unreliable goofball in Sales? You don’t want him even seeing what’s in your shared folder.

Of course, setting up all those levels of control means more work and more complexity.

The following pages tackle these three methods one at a time.

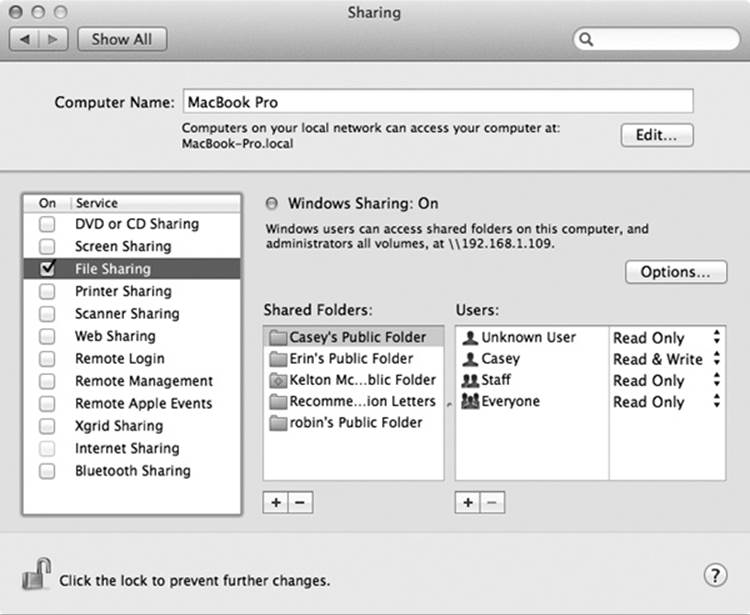

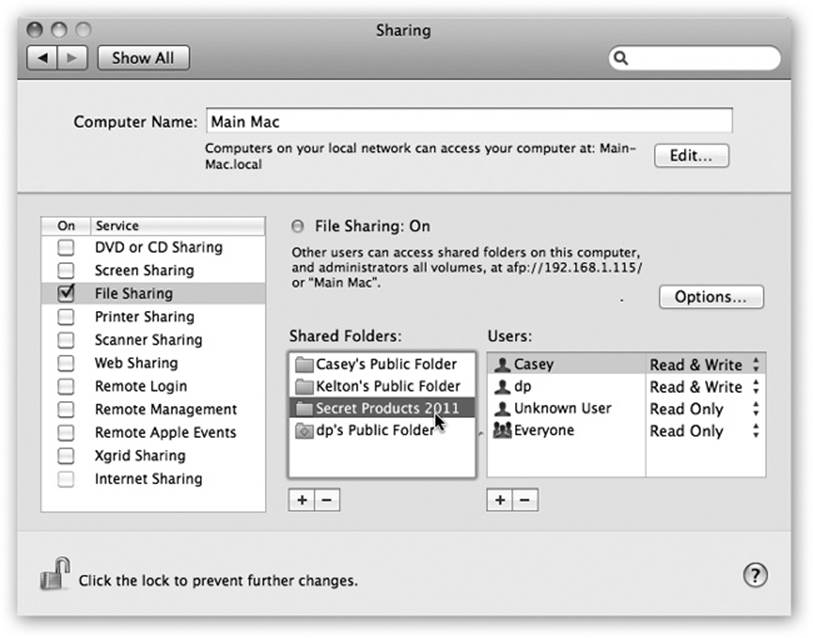

Figure 15-2. Here’s the master switch that makes your Public folder (and any other folders you designate) available to other people on the network. You can edit the Computer Name, if you like. Your Mac will appear on the network with this name. Make it nice and descriptive, such as Front Desk iMac.

AirDrop

AirDrop is one of OS X’s star attractions. It’s a breakthrough in speed, simplicity, and efficiency. There’s no setup, no passwords involved. It lets you copy files to someone else’s Mac up to 30 feet away, instantly and wirelessly; you don’t need an Internet connection or even a WiFi network. It works on a flight, a beach, or a sailboat in the middle of the Atlantic. It also works if you are on a WiFi network, doing other things online.

To give someone a file, you have a choice.

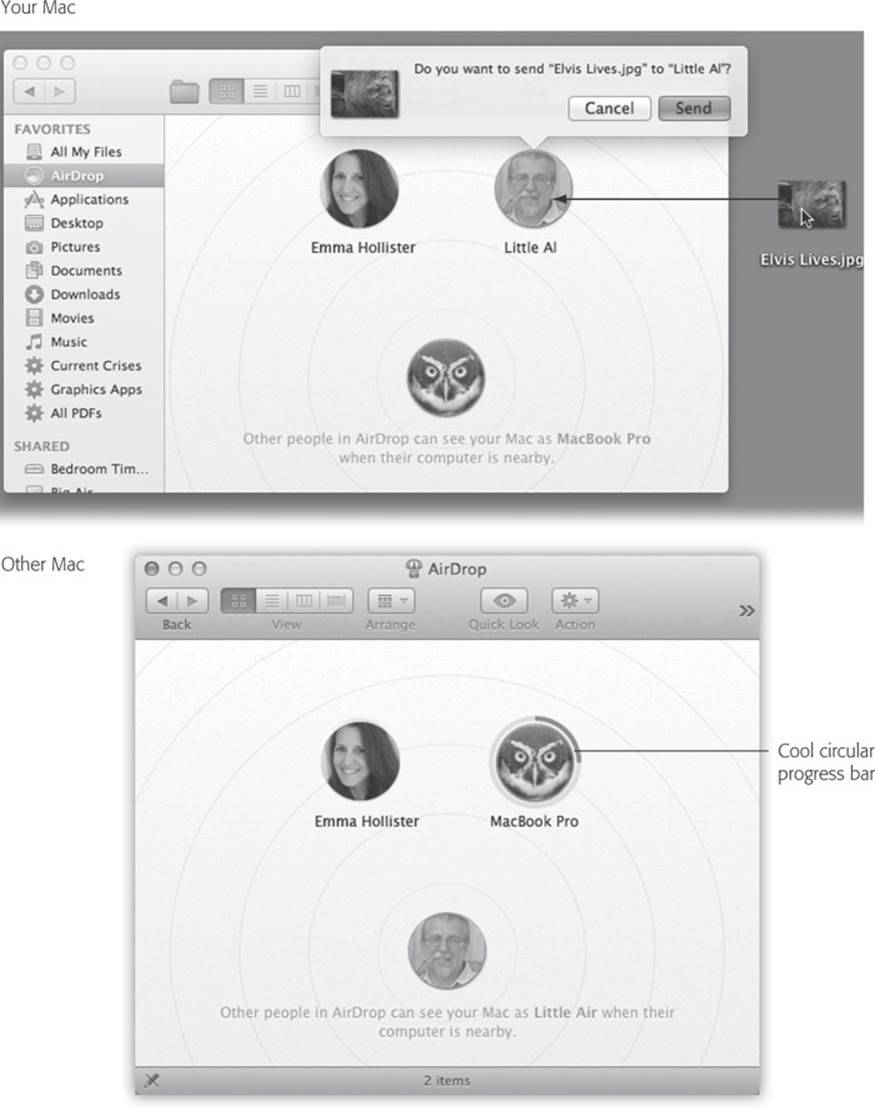

Figure 15-3. Top: If there are other Lion or later Macs within about 30 feet, you see their logged-in users’ icons here. Usually, the icons display the Mac owners’ account pictures; but if they have facial photos in your Contacts, then you see those instead. Bottom: Here’s what you see if you’re the recipient (and have clicked Save in the confirmation box). To find your newly arrived goodies, open your Downloads folder.

Drag into the AirDrop window

Each of you must open your AirDrop window. To do that, click the AirDrop icon (at the top of the Sidebar in any Finder window), choose Go→AirDrop, or press Shift-⌘-R.

NOTE

If you don’t see AirDrop in the Sidebar, and you’re sure you’re using Lion or later, it’s because somebody turned off its checkbox in Finder→Preferences→Sidebar. Hiding the AirDrop icon in this way means you can’t use the feature at all, at least not by dragging an icon into a window. You can still use the Share button as described below.

The window shown in Figure 15-3 appears. After a moment, it fills up with icons for all the people nearby who are running a wireless Lion or later Mac—and have opened their AirDrop windows. They don’t have to do anything else; their icons show up automatically in your AirDrop window.

Now drag a file or folder icon, or several, onto the icon of the intended recipient. When the Mac asks if you’re sure, click Send or press Return.

The recipient now sees a message that says, “[Other guy’s Mac] wants to send you [the file’s name].” And there are three options: Save and Open, Decline, and Save.

If the lucky winner clicks one of the Save buttons, then the file transfer proceeds automatically. A progress bar wraps around the other person’s icon in the AirDrop window—cute. The transfer is encrypted, so evildoers nearby have no clue what you’re transferring (or even that you’re transferring).

The file winds up in the other guy’s Downloads folder.

TIP

The Downloads folder generally sits on the Dock, so it’s easy to find. But your recipient can also choose Go→Downloads, or press Option-⌘-L, to jump there.

Use the Share Sheet

There’s another, more direct way to send a file by AirDrop. Click the icon of the file you want to send (or select several). Now choose the Share→AirDrop command.

And where is that command? Everywhere. It’s in the shortcut menu that appears when you right-click (or two-finger click) an icon. It’s in the ![]() icon at the top of every Finder window, and at the top of every Quick Look window. (See The Share Button for more on the Share button.)

icon at the top of every Finder window, and at the top of every Quick Look window. (See The Share Button for more on the Share button.)

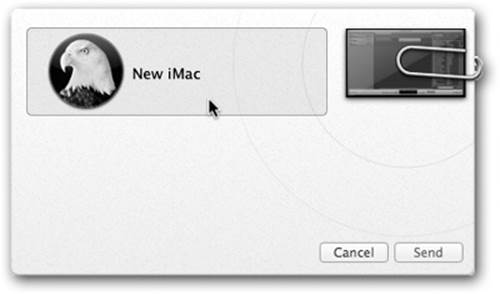

Now a miniature version of the AirDrop window appears; see Figure 15-4.

Once you’ve clicked the recipient’s icon, and the recipient agrees to receive (by clicking Save and Open, or Save), the transfer begins, just as described above.

All right. So if AirDrop is so great, why doesn’t it wipe out all other forms of file transfer and save this book a bunch of pages? Because (a) it works only on Macs running Lion or later, (b) it works only wirelessly, and (c) it’s a one-way street. Other people can’t take files from your Mac—you have to shove the files to them.

NOTE

Actually, there’s another limitation: AirDrop doesn’t work on some older Mac models. It works on the MacBook Pro (made since late 2008), MacBook Air (late 2010), MacBook (late 2008), iMac (early 2009), Mac mini (mid-2010), and Mac Pro (mid-2010).

Figure 15-4. The icons of nearby AirDrop-happy Macs show up in this fun-sized version of the regular AirDrop window (if their AirDrop windows are open, of course). You’ve already said which files you want to send; now you just have to specify who gets them. Click the Mac’s icon and then click Send.

If you can get past those limitations, though, there’s a lot of great stuff in AirDrop:

§ If you see someone’s name beneath her icon in the AirDrop window, that means that she’s in your Contacts and has signed in with her Apple ID. That’s an extra bit of confidence that she is who her icon says she is.

§ AirDrop works by creating a temporary two-computer wireless network. That’s why it works even if you’re not in a WiFi hotspot. It does, however, require both computers to have WiFi turned on, which you can check by opening the ![]() menu.

menu.

§ If you’re the one receiving a file, you can cancel a half-finished transfer by clicking the ![]() button on the progress bar that wraps around the sender’s icon in the AirDrop window. (Another way: If your Downloads folder is set to Stack view, you can click the

button on the progress bar that wraps around the sender’s icon in the AirDrop window. (Another way: If your Downloads folder is set to Stack view, you can click the ![]() button in the corner of the file’s icon.)

button in the corner of the file’s icon.)

§ AirDrop doesn’t work unless both of you have opened your AirDrop windows in the Finder. If you close your AirDrop window, or even click outside that window, your Mac disappears from everyone else’s AirDrop screens.

Sharing Your Public Folder

AirDrop is the simplest and happiest way to share files, no doubt about it. But it requires Lion/Mountain Lion/Mavericks on both Macs, it works only wirelessly, and it’s a one-way street (you have to initiate the file handoff).

The next-simplest file-sharing method eliminates all those limitations. It’s the Public-folder method.

Inside your Home folder, there’s a folder called Public. (Inside everybody’s Home folder is a folder called Public.)

Anything you put into this folder is automatically available to everyone else on the network. They don’t need a password, they don’t need an account on your Mac—they just have to be on the same network, wireless or wired. They can put files here or copy things out.

To make your Public folder available to your networkmates, you have to turn on the File Sharing master switch. Choose ![]() →System Preferences, click Sharing, and then turn on File Sharing (as shown back in Figure 15-2).

→System Preferences, click Sharing, and then turn on File Sharing (as shown back in Figure 15-2).

Now round up the files and folders you want to share with all comers on the network and drag them into your Home→Public folder. That’s all there is to it.

NOTE

You may notice that there’s already something in your Public folder: a folder called Drop Box. It’s there so that other people can give you files from across the network, as described later in this chapter.

So now that you’ve set up Public folder sharing, how are other people supposed to access your Public folder? See Accessing Shared Files.

Sharing Any Folder

If the Public-folder method seems too simple and restrictive, then you can graduate to the “share any folder” method. In this scheme, you can make any file, folder, or disk available to other people on the network.

The advantage here is that you don’t have to move your files into the Public folder; they can sit right where you have them. And this time, you can set up elaborate sharing privileges (also known as permissions) that grant individuals different amounts of access to your files.

This method is more complicated to set up than that Public-folder business. In fact, just to underline its complexity, Apple has created two different setup procedures. You can share one icon at a time by opening its Get Info window; or you can work in a master list of shared items in System Preferences.

The following pages cover both methods.

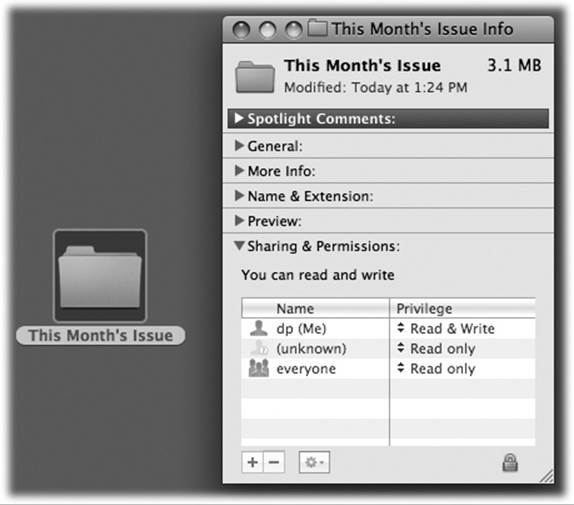

The Get Info method

Here’s how to share a Mac file, disk, or folder disk using its Get Info window.

The following steps assume you’ve turned on ![]() →System Preferences→Sharing→File Sharing, as shown in Figure 15-2.

→System Preferences→Sharing→File Sharing, as shown in Figure 15-2.

1. Highlight the folder or disk you want to share. Choose File→Get Info.

The Get Info dialog box appears (Figure 15-5). Expand the General panel, if it’s not already visible.

NOTE

Sharing an entire disk means that every folder and file on it is available to anyone you give access to. On the other hand, by sharing only a folder or two, you can keep most of the stuff on your hard drive private, out of view of curious network comrades. Sharing only a folder or two does them a favor, too, by making it easier for them to find the files they’re supposed to have. This way, they don’t have to root through your entire drive looking for the folder they actually need.

2. Turn on “Shared folder.”

Enter your administrative password, if necessary.

TIP

To help you remember what you’ve made available to other people on the network, a gray banner labeled “Shared Folder” appears across the top of any Finder window you’ve shared. It even appears at the top of the Open and Save dialog boxes.

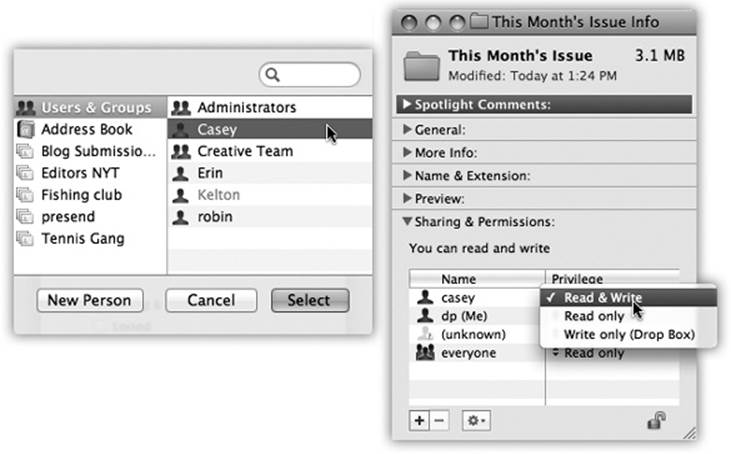

Figure 15-5. The file-sharing permissions controls are here, in the Get Info box for any file, folder, or disk.

OK, this disk or folder is now shared. But with whom?

3. Expand the Sharing & Permissions panel, if it’s not already visible. Click the ![]() icon and enter your administrator’s password.

icon and enter your administrator’s password.

The controls in the Sharing & Permissions area spring to life and become editable. At the bottom of the Info panel is a little table. The first column can display the names of individual account holders, like Casey or Chris, or groups of account holders, like Everyone or Accounting Dept.

The second column lists the privileges each person or group has for this folder.

Now, the average person has no clue what “privileges” means, and this is why things get a little hairy when you’re setting up folder-by-folder permissions. But read on; it’s not as bad as it seems.

4. Edit the table by adding people’s names. Then set their access permissions.

At the moment, your name appears in the Name column, and it probably says Read & Write in the Privilege column. In other words, you’re currently the master of this folder. You can put things in, and you can take things out.

If you just want to share files with yourself, so you can transfer them from one computer to another, you can stop here.

If you want to share files with other people—well, at the moment, the privileges for Everyone are probably set to “Read only.” Other people can see this folder, but they can’t do anything with it.

Your job is to work through this list of people, specifying how much control each person has over the file or folder you’re sharing.

To add the name of a person or group, click the ![]() button below the list. The list shown in Figure 15-6 appears.

button below the list. The list shown in Figure 15-6 appears.

Figure 15-6. This list includes every account holder on your Mac, plus groups you’ve set up, plus the contents of your address book. One by one, you can add them to the list of lucky sharers of your files or folders—and then change the degree of access they have to the stuff you’re sharing.

Now click a name in the list. Then, from the Privilege pop-up menu, choose a permissions setting.

o Read & Write gives the most access of all. This person, like you, can add, change, or delete any file in the shared folder, or make any changes she likes to a document. Give Read & Write permission to people you trust not to mess things up.

o Read only means “Look but don’t touch.” This person can see what’s in the folder (or file) and can copy it, but he can’t delete or change the original. It’s a good setting for distributing company documents or making source files available to your minions.

o Write only (Drop Box) means that other people can’t even open the folder. They can drop things into it, but it’s like a mail slot: The letter disappears into the slot, and then it’s too late for them to change their minds. As the folder’s owner, you can do what you like with the deposited goodies. This drop-box effect is great when you want students, coworkers, or family members to be able to turn things in to you—homework, reports, scandalous diaries—without running the risk that someone else might see those documents. (This option doesn’t appear for documents—only disks and folders.)

o No access is an option only for Everyone. It means that other people can see this file or folder’s icon but can’t do a thing with it.

TIP

Usually, you’ll want the privileges for the folder to also apply to everything inside it; it would be a real drag to have to change the sharing privileges of the contents one icon as a time. That’s why the ![]() menu at the bottom of the Get Info box has a command called “Apply to enclosed items.”

menu at the bottom of the Get Info box has a command called “Apply to enclosed items.”

5. Close the Get Info window.

Now the folder is ready for invasion from across the network.

The System Preferences method

It’s very convenient to turn on sharing one folder at a time, using the Get Info window. But there’s another way in, too, one that displays all your shared stuff in one handy master list.

To see it, choose ![]() →System Preferences. Click Sharing. Click File Sharing (and make sure it’s turned on).

→System Preferences. Click Sharing. Click File Sharing (and make sure it’s turned on).

Now you’re looking at a slightly different kind of permissions table, shown in Figure 15-7. It has three columns:

§ Shared folders. The first column lists the files, folders, and disks you’ve shared. You’ll probably see that every account’s Public folder is already listed here, since they’re all shared automatically. (You can turn off sharing for a Public folder, too, just by clicking it and then clicking the ![]() button.)

button.)

But you can add more icons to this list. Either drag them into the list directly from the desktop or a Finder window, or click the ![]() sign, navigate to the item you want to share, select it, and then click Add. Either way, that item now appears in the Shared Folders list.

sign, navigate to the item you want to share, select it, and then click Add. Either way, that item now appears in the Shared Folders list.

§ Users. When you click a shared item, the second column sprouts a list of who gets to work with it from across the network. You’re listed here, of course, since it’s your stuff. There’s also a listing here for Everyone, which really means, “everyone else”—that is, everyone who’s not specifically listed here.

You can add to this list, too. Click ![]() to open the person-selection box shown in Figure 15-6. It lists the other account holders on your Mac and some predefined groups, as well as the contents of your Contacts.

to open the person-selection box shown in Figure 15-6. It lists the other account holders on your Mac and some predefined groups, as well as the contents of your Contacts.

NOTE

Most of the Contacts people don’t actually have accounts on this Mac, of course. If you choose somebody from this list, you’re asked to make up an account password. When you click Create Account, you’ve actually created a Sharing Only account on your Mac for that person. When you return to the Accounts pane of System Preferences, you’ll see that new person listed.

Figure 15-7. Hiding in System Preferences is a list of every disk and folder you’ve shared. To stop sharing something, click it and click the ![]() button. To share a new disk or folder, drag its icon off the desktop, or out of its window, directly into the Shared Folders list.

button. To share a new disk or folder, drag its icon off the desktop, or out of its window, directly into the Shared Folders list.

Double-click a person’s name to add him to the list of people who can access this item from over the network, and then set up the appropriate privileges (described next).

To remove someone from this list, just click the name and then click the ![]() button.

button.

§ Users. This other column under the Users heading lets you specify how much access each person has to this folder. Your choices, once again, are Read & Write (full access to change or delete this item’s contents); Read Only (open or copy, but can’t edit or delete); and Write Only (Drop Box), which lets the person put things into this disk or folder but not open it or see what else is in it.

For the Everyone group, you also get an option called No Access, which means that this item is completely off limits to everyone else on the network.

And now, having slogged through all these options and permutations, your Mac is ready for invasion from across the network.

Accessing Shared Files

The previous pages have described setting up a Mac so people at other computers can access its files. There’s an easy, limited way (use the Public folder) and a more elaborate way (turn on sharing settings for each folder individually).

Now comes the payoff to both methods: sitting at another computer and connecting to the one you set up. There are two ways to go about it: You can use the Sidebar, or you can use the older, more flexible Connect to Server command. The following pages cover both methods.

Connection Method A: Use the Sidebar

Suppose, then, that you’re seated in front of your Mac, and you want to see the files on another Mac on the network. Proceed like this:

§ 1. Open any Finder window.

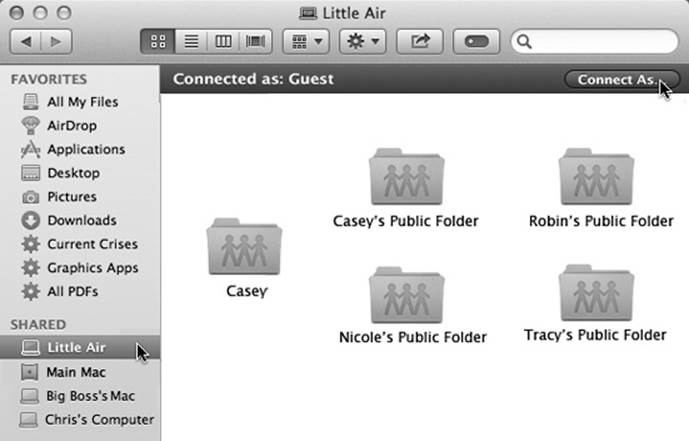

In the Shared category of the Sidebar at the left side of the window, icons for all the computers on the network appear. See Figure 15-8.

TIP

The same Sidebar items show up in the Save and Open dialog boxes of your programs, too, making the entire network available to you for opening and saving files.

If you don’t see a certain Mac’s icon here, it might be turned off, it might not be on the network, or it might have File Sharing turned off.

NOTE

Or it might not have the right file-sharing type turned on. To check, open System Preferences→Sharing; click Sharing and then Options. You’ll see checkboxes for AFP and SMB. Your computers can’t see each other if they don’t have one of these options in common.

If you don’t see any computers at all in the Sidebar, then your computer might not be on the network. Or maybe you’ve turned off the checkboxes for Connected Servers and Bonjour Computers in Finder→Preferences→Sidebar.

TIP

If the other Mac is just asleep, it still shows up in the Sidebar, and you can wake it up to get at it. How is that possible? Through the miracle of the Wake for Network Access feature described on Checkbox Options.

If there are a lot of computer icons in the Sidebar, or if you’re on a corporate-style network that has the sub-chunks known as workgroups, you may also see an icon called All. Click it to see the full list of network entities that your Mac can see: not just individual Mac, Windows, and Unix machines, but also any “network neighborhoods” (limbs of your network tree). For example, you may see the names of network zones (clusters of machines, as found in big companies and universities).

Or, if you’re trying to tap into a Windows machine, open the icon representing the workgroup (computer cluster) that contains the machine you want. In small office networks, it’s usually called MSHOME or WORKGROUP. In big corporations, these workgroups can be called almost anything—as long as it’s no more than 15 letters long with no punctuation. (Thanks, Microsoft.)

If you do see icons for workgroups or other network “zones,” double-click until you’re seeing the icons for individual computers.

NOTE

If you’re a network nerd, you may be interested to note that OS X can “see” servers that use the SMB/CIFS, NFS, FTP, and WebDAV protocols running on OS X Server, Unix, Linux, Novell NetWare, and Windows servers (NT, 2000, XP, Vista, Windows 7 and 8). But the Sidebar reveals only the shared computers on your subnet (your local, internal office network). (It also shows Back to My Mac if it’s set up; see Screen sharing with Back to My Mac.)

Figure 15-8. Macs appear in the Sidebar with whatever names they’ve been given in System Preferences→Sharing. Their tiny icons usually resemble the computers themselves. Other computers (like Windows PCs) look like generic PCs.

§ 2. Click the computer whose files you want to open.

In the main window, you now see the Public Folder icons for each account holder on that computer: Mom, Dad, Sissy, whatever, as shown in Figure 15-8. (They may have shared other folders with you, too.) If you have an account on the other computer, you’ll see a folder representingyour stuff, too. At this point, you’re considered a guest.

NOTE

This amount of access depends on a setting in System Preferences→Users & Groups. Click the Guest account to see it: “Allow guests to connect to shared folders.” That checkbox is usually turned on—but it’s something to check if you can’t seem to connect.

From here, the remaining instructions diverge, depending on whether you want to access other people’s stuff or your stuff. That’s why there are two alternative versions of step 3 here:

§ 3a. If you want to access the stuff that somebody else has left for you, double-click that person’s Public folder.

Instantly, that folder’s contents appear in the Finder window.

In this situation, you’re only a guest. You don’t have to bother with a password. On the other hand, the only thing you can generally see inside the other person’s account folder is his Public folder.

TIP

Actually, you might see other folders here—if the account holder has specifically shared them and decided that you’re important enough to have access to them.

One thing you’ll find inside the Public folder is the Drop Box folder. This folder exists so that you can give files and folders to the other person. You can drop any of your own icons onto the Drop Box folder—but you can’t open the Drop Box folder to see what other people have put there. It’s one-way, like a mail slot in somebody’s front door.

If you see anything else at all in the Public folder you’ve opened, then it’s stuff the account holder has copied there for the enjoyment of you and your networkmates. You’re not allowed to delete anything from the other person’s Public folder or make changes to anything in it.

You can, however, open those icons, read them, or even copy them to your Mac—and then edit your copies.

POWER USERS’ CLINIC: WHAT YOU CAN SEE

Precisely which other folders you can see on the remote Mac depend on what kind of account you have there: Guest, Standard, or Administrator. (See the previous chapter.)

If you’re using the Guest account, you can see only the Public folders. The rest of the Mac is invisible and off limits to you. (You may see additional folders if somebody turned on sharing for them.)

If you have a Standard account, you can see other people’s Public and Drop Box folders, plus your own Home folder. (Again, somebody may have made other folders available.)

If you’re an administrator, you get to see icons for the account holders’ Public folders and the hard drive itself to which you’re connecting. In fact, you even get to see the names of any other disks connected to that Mac.

If you, O lucky administrator, open the hard drive, you’ll discover that you also have the freedom to see and manipulate the contents of the Applications, Desktop, Library, and Users→Shared folders.

You can even see what folders are in other users’ Home folders, although you can’t open them or put anything into them.

Finally, there’s something called the root user. This account has complete freedom to move or delete any file or folder anywhere, including critical system files that could disable your Mac. It also requires a degree in Unix.

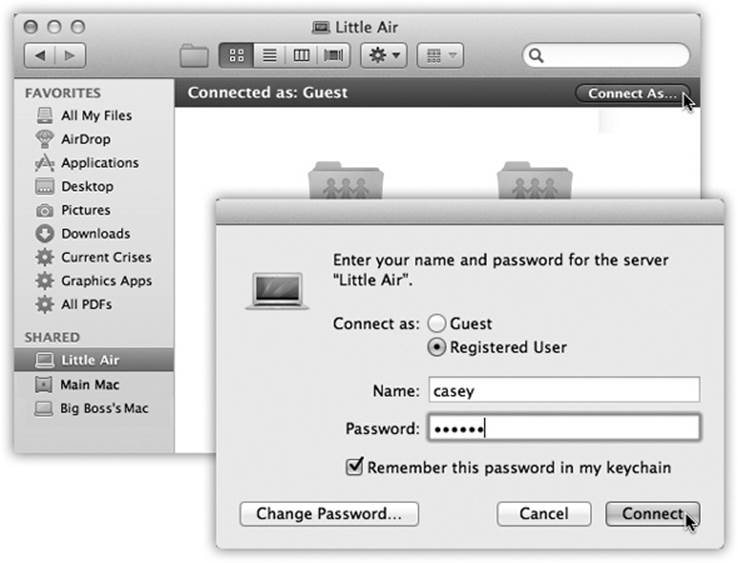

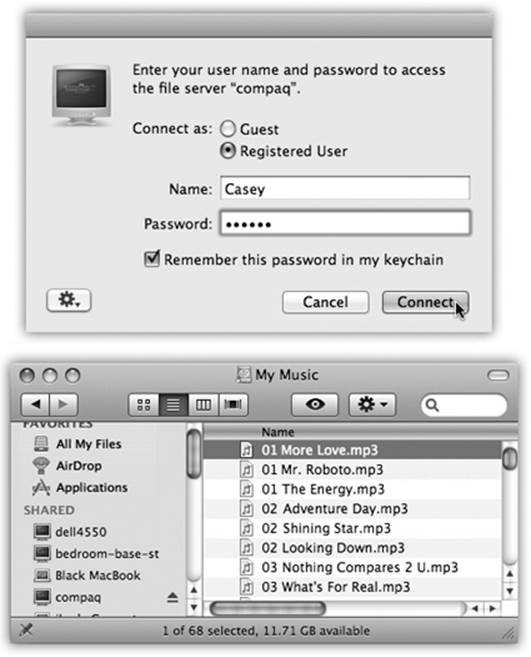

§ 3b. To access your own Home folder on the other Mac, click the Connect As button (Figure 15-9). Sign in as usual.

When the “Connect to the file server” box appears, you’re supposed to specify your account name and password (from the Mac you’re tapping into). This is the same name and password you’d use to log in if you were actually sitting at that machine.

Figure 15-9. You can sign into your account on another Mac on the network (even while somebody else is using that Mac in person). Click Connect As and then enter your name and password. Turn on “Remember this password in my keychain” to speed up the process for next time. The Change Password button lets you change your account password on the other machine. No matter which method you use to connect to a shared folder or disk, its icon shows up in the Sidebar.

Type your account name (long or short version) and password. And if you didn’t set up a password for your account, leave the password box empty.

TIP

The dialog box shown in Figure 15-9 includes the delightful and timesaving “Remember this password in my keychain” option, which makes the Mac memorize your password for a certain disk so you don’t have to type it—or even see this dialog box—every darned time you connect. (If you have no password, though, the “Remember password” doesn’t work. You’ll have to confront—and press Return to dismiss—the “Connect to the file server” box every time.)

When you click Connect (or press Return or Enter), the other Mac’s icon shows up in your Sidebar, and its contents appear in the main window. (The other Mac’s icon may also show up on the desktop, if you’ve turned on the “Connected Servers” option in Finder→Preferences→Sidebar.)

TIP

Once you’ve connected to a Mac using your account, the other Mac has a lock on your identity. You’ll be able to connect to the other Mac over and over again during this same computing session, without ever having to retype your password.

In the meantime, you can double-click icons to open them, make copies of them, and otherwise manipulate them exactly as though they were icons on your own hard drive. Depending on what permissions you’ve been given, you can even edit or trash those files.

TIP

There’s one significant difference between working with “local” icons and working with those that sit elsewhere on the network. When you delete a file from another Mac on the network, either by pressing the Delete key or by dragging it to the Trash, a message appears to let you know that you’re about to delete that item instantly and permanently. It won’t simply land in the Trash “folder,”awaiting the Empty Trash command.

You can even use Spotlight to find files on that networked disk. If the Mac across the network is running a Leopard or later OS X version, in fact, you can search for words inside its files, just as though you were sitting in front of it. If not, you can still search for text in files’ names.

Connection Method B: Connect to Server

The Sidebar method of connecting to networked folders and disks is practically effortless. It involves nothing more than clicking your way through folders—a skill that, in theory, you already know.

But the Sidebar method has its drawbacks. For example, the Sidebar doesn’t let you type in a disk’s network address. As a result, you can’t access any shared disk on the Internet (an FTP site, for example), or indeed anywhere beyond your local subnet (your own small network).

Fortunately, there’s another way. When you choose Go→Connect to Server, you get the dialog box shown in Figure 15-10. You’re supposed to type in the address of the shared disk you want.

For example, from here you can connect to the following:

§ Everyday Macs on your network. If you know the IP address of the Mac you’re trying to access (you geek!), you can type nothing but its IP address into the box and then hit Connect. Or you can just type its Bonjour name, something like this: afp://upstairs-PowerMac.local/.

GEM IN THE ROUGH: FASTER WAYS TO CONNECT NEXT TIME

If you expect that you might want to access a shared disk or folder again later, take a moment to make an alias of it. The easiest way is to press Option-⌘ as you drag it out of the window where it first appears.

Next time, you can bring it back to your screen just by double-clicking the alias. And if you turned on “Remember this password in my keychain,” you won’t even be asked for your name and password again.

Similarly, if you put an alias like this onto the Dock, you can bring it back to your screen later just by clicking its icon.

You can even drag the alias into the Login Items window described on Phase 4: Login Items (Startup Items). Now the disk appears on your desktop automatically each time you log in—the most effortless arrangement of all.

TIP

To find out your Mac’s IP address, open the Network pane of System Preferences. There, near the top, you’ll see a message like this: “AirPort is connected to Tim’s Hotspot and has the IP address 192.168.1.113.” That’s your IP address.

To see your Bonjour address, open the Sharing pane of System Preferences. Click File Sharing. Near the top, you’ll see the computer name with “.local” tacked onto its name—and hyphens instead of spaces—like this: Little-MacBook.local.

Figure 15-10. The Sidebar method of connecting to shared disks and folders is quick and easy, but it doesn’t let you connect to certain kinds of disks. The Connect to Server method entails plodding through several dialog boxes, but it can find just about every kind of networked disk.

After you enter your account password and choose the shared disk or folder you want, you’re connected exactly as though you had clicked Connect As (Figure 15-9).

The next time you open the Connect to Server dialog box, OS X remembers that address, as a courtesy to you, and shows it pre-entered in the Address field.

§ Macs across the Internet. If your Mac has a permanent (static) IP address, then the computer itself can be a server, to which you can connect from anywhere in the world via the Internet.

§ Windows machines. Find out the PC’s IP address or computer name, and then use this format for the address: smb://192.168.1.34 or smb://Cheapo-Dell.

After a moment, you’re asked to enter your Windows account name and password, and then to choose the name of the shared folder you want. When you click OK, the shared folder’s contents appear in the window, ready to use, and the computer’s icon appears in your Sidebar. (More on sharing with Windows PCs later in this chapter.)

TIP

If you know the name of the shared folder, you can add that after a slash, like this: smb://192.168.4.23/sharedstuff. You save yourself one dialog box.

§ NFS servers. If you’re on a network with Unix machines, you can tap into one of their shared directories using this address format: nfs://Machine-Name/pathname, where Machine-Name is the computer’s name or IP address, and pathname is the folder path to the shared item you want.

§ FTP servers. OS X makes it simple to bring FTP servers onto your screen, too. (These are the drives, out there on the Internet, that store the files used by Web sites.)

In the Connect to Server dialog box, type the FTP address of the server you want, like this: ftp://www.apple.com. If the site’s administrators have permitted anonymous access—the equivalent of a Guest account—that’s all there is to it. A Finder window pops open, revealing the FTP site’s contents.

If you need a password for the FTP site, however, you’re now asked for your name and password.

TIP

You can eliminate that password-dialog-box step by using this address format: ftp://yourname:yourpassword@www.apple.com.

Once you type it and press Return, the FTP server’s icon appears in the Sidebar. Its contents appear, too, ready to open or copy.

§ WebDAV server. This special Web-based shared disk requires a special address format, something like this: http://Computer-Name/pathname.

In each case, once you click OK, you may be asked for your name and password.

GEM IN THE ROUGH: HELLO, BONJOUR

Throughout this chapter, and throughout this book, you’ll encounter rituals in which you’re supposed to connect to another Mac, server, or printer by typing in its IP address (its unique network address).

But first of all, IP addresses are insanely difficult to memorize (192.179.248.3, anyone?). Second, networks shouldn’t require you to deal with them anyway. If a piece of equipment is on the network, it should announce its presence, rather than making you specifically call for it by name.

Now you can appreciate the beauty of Bonjour (once known as Rendezvous), an underlying OS X networking technology that lets networked gadgets detect one another on the network automatically and recognize one another’s capabilities.

It’s Bonjour at work, for example, that makes other Macs’ names show up in your iTunes program so you can listen to their music from across the network. Bonjour is also responsible for filling up your Bonjour buddy list in Messages automatically, listing everyone who’s on the same office network; for making shared Macs’ names show up in the Sidebar’s Shared list; and for making the names of modern laser printers from HP, Epson, or Lexmark appear like magic in the list of printers in the Print dialog box.

It’s even more tantalizing to contemplate the future of Bonjour. If electronics companies show interest (and some have already), you may someday be able to connect the TV, stereo, and DVD player with just a couple of Ethernet cables, or even wirelessly, instead of a rat’s nest of audio and video cables.

For most of us, that day can’t come soon enough.

And now, some timesaving features in the Connect to Server box:

§ Once you’ve typed a disk’s address, you can click ![]() to add it to the list of server favorites. The next time you want to connect, you can just double-click its name.

to add it to the list of server favorites. The next time you want to connect, you can just double-click its name.

§ The clock-icon pop-up menu lists Recent Servers—computers you’ve accessed recently over the network. If you choose one of them from this pop-up menu, you can skip having to type in an address.

TIP

Like the Sidebar network-browsing method, the Connect to Server command displays each connected computer as an icon in your Sidebar, even within the Open or Save dialog boxes of your programs. You don’t have to burrow through the Sidebar’s Network icon to open files from them, or to save files onto them.

Disconnecting Yourself

When you’re finished using a shared disk or folder, you can disconnect from it as shown in Figure 15-11.

Figure 15-11. To disconnect from a shared network disk or folder, click the other computer’s icon in the Sidebar. Then click Disconnect at the top-right corner of the window.

Disconnecting Others

In OS X, you really have to work if you want to know whether other people on the network are accessing your Mac. You have to choose System Preferences→Sharing→File Sharing→Options. There you’ll see something like, “Number of users connected: 1.”

Maybe that’s because there’s nothing to worry about. You certainly have nothing to fear from a security standpoint, since you control what they can see on your Mac. Nor will you experience much computer slowdown as you work, thanks to OS X’s prodigious multitasking features.

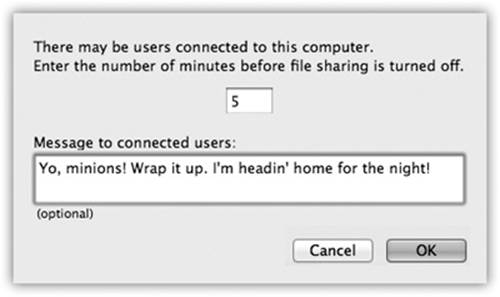

Still, if you’re feeling particularly antisocial, you can slam shut the door to your Mac. Just open System Preferences→Sharing and turn off File Sharing.

If anybody is, in fact, connected to your Mac at the time (from a Mac), you, the door-slammer, get to see the dialog box in Figure 15-12, which lets you send a little warning or farewell message to whomever’s connected to your Mac.

Figure 15-12. This dialog box asks you how much notice you want to give your coworkers that they’re about to be disconnected—and what message to send them before the ax falls.

If nobody is connected right now, then your Mac instantly becomes an island once again.

Networking with Windows

Windows may dominate the corporate market, but there are Macs in the offices of America—and there are PCs in homes. Fortunately, Macs and Windows PCs can see each other on the network, with no special software (or talent) required.

In fact, you can go in either direction. Your Mac can see shared folders on a Windows PC, and a Windows PC can see shared folders on your Mac.

It goes like this.

Seated at the Mac, Seeing the PC

Suppose you have a Windows PC and a Mac on the same wired or wireless network. Here’s how you get the Mac and PC chatting:

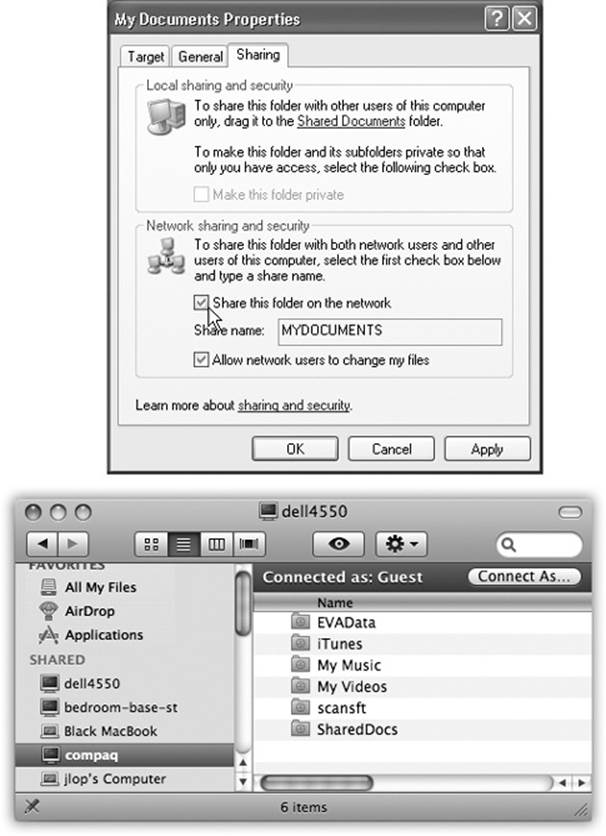

1. On your Windows PC, share some files.

This isn’t really a book about Windows networking (thank heaven), but here are the basics.

Just as on the Mac, there are two ways to share files in Windows. One of them is super-simple: You just copy the files you want to share into a central, fully accessible folder. As long as nobody has turned off the Guest-access feature, no passwords, accounts, or other steps are required.

In Windows XP, that special folder is the Shared Documents folder, which you can find by choosing Start→My Computer. Share it on the network as shown in Figure 15-13, top.

Figure 15-13. Top: To share a folder in Windows, right-click it, choose Properties, and then turn on “Share this folder on the network.” In the “Share name” box, type a name for the folder as it will appear on the network. (No spaces are allowed). Bottom: Back in the safety of OS X, click the PC’s name in the Sidebar. (If it’s part of a workgroup, click All, and then your workgroup name first.) Next, click the name of the shared computer. If the files you need are in a Shared Documents or Public folder, no password is required. You see the contents of the PC’s Shared Documents folder or Public folder, as shown here. Now it’s just like file sharing with another Mac. If you want access to any other shared folder, click Connect As, and see Figure 15-14.

In Windows Vista, it’s the Public folder, which appears in the Navigation pane of every Explorer window. (In Vista, there’s one Public folder for the whole computer, not one per account holder.)

In Windows 7, there’s a Public folder in each library. That is, there’s a Public Documents, Public Pictures, Public Music, and so on.

NOTE

There is no system of Public folders in Windows 8 and 8.1—but if you upgraded your PC from an earlier Windows version, the Public folders are still there and work the same way.

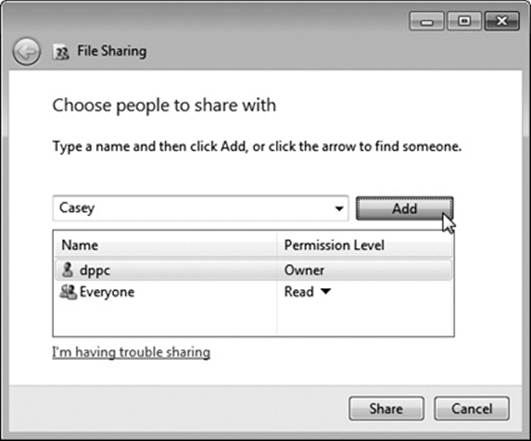

The second, more complicated method is the “share any folder” method, just as in OS X. In XP or Vista, you right-click the folder you want to share, choose Properties from the shortcut menu, click the Sharing tab, and turn on “Share this folder on the network” (Figure 15-13, top). In Windows 7, use the Share With menu at the top of any folder’s window; in Windows 8 or 8.1, use the Share tab on the ribbon at the top of any Explorer window at the desktop.

Repeat for any other folders you want to make available to your Mac.

TROUBLESHOOTING MOMENT: WINDOWS 7 TIPS

Windows 7 is a very Mac-like version of Windows, but making it share nicely with the Mac still requires a few setup steps.

First, make sure you’ve shared everything you want to share on the Windows 7 machine. For example, suppose you want to share your entire personal folder (the equivalent of the Mac’s Home folder).

To do that, choose Start→[your name]. In the window that opens, choose “Share with”→“Specific people.” In the resulting dialog box, you’ll see that you are already permitted to access this folder, as shown here; unless you want to add someone else, just click Share and then Done.

Now, on the Mac, in the Finder, choose Go→Connect to Server. Type smb://SuperDell, or whatever your PC’s name is. (And how do you find that out? Open the Start menu; right-click Computer; from the shortcut menu, choose Properties. You’ll see the computer name in the middle of the resulting info screen.)

On the Mac, after typing the PC’s name into the Connect to Server box, click Connect. After a moment, you’re asked for your account name and password, as it appears on the PC.

Enter these credentials—turn on “Remember my password” if you want to be spared this rigmarole the next time—and then click Connect.

Now you’re shown a list of disks and folders you shared on the Windows PC. Double-click the one you want. Presto: It appears in a Finder window, ready to access!

(If you discover you can copy stuff out of these folders but can’t put stuff into them, check the sharing permissions on the Windows side.)

Finally, for heaven’s sake, make an alias of the Windows folder or disk on the Mac so you can just double-click to open it the next time!

2. On the Mac, open any Finder window.

The shared PCs appear as individual computer names in the Sidebar.

(If you work in a big company, you may have to click the All icon to see the icons of their workgroups—network clusters. Unless you or a network administrator changed it, the workgroup name is probably MSHOME or WORKGROUP.)

TIP

You can also access the shared PC via the Connect to Server command, as described on Connection Method B: Connect to Server. You could type into it smb://192.168.1.103 (or whatever the PC’s IP address is) or smb://SuperDell (or whatever its name is) and hit Return—and then skip to step 5. In fact, using the Connect to Server method often works when the Sidebar method doesn’t.

3. Double-click the name of the computer you want.

If you’re using one of the simple file-sharing methods on the PC, as described above, that’s all there is to it. The contents of the Shared Documents or Public folder now appear on your Mac screen. You can work with them just as you would your own files.

If you’re using one of the “shared folder” methods, read on.

TROUBLESHOOTING MOMENT: WHEN THE MAC DOESN’T SEE THE PC

Are you having trouble getting your PC’s icon to show up in your Finder’s Sidebar?

Now, you can probably connect to the PC using the Mac’s Go→Connect to Server command, but the Sidebar would be a lot more convenient.

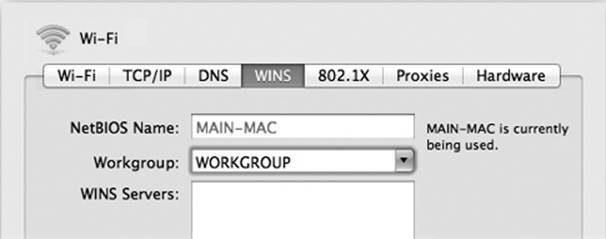

And the problem is probably that the Mac doesn’t know anything about Windows workgroups.

Even a lowly home PC is part of a workgroup (a corporate cluster), whether it knows it or not. And until your Mac is part of that very tiny club, it won’t be able to see your PCs, and they won’t be able to see it.

So if you’re having no luck with this whole Mac-PC thing, try this. First, find out what your PC thinks its workgroup is. (It’s usually either WORKGROUP or MSHOME.) Click Start, and then right-click or two-finger click Computer. From the shortcut menu, choose Properties. In the resulting info screen, you’ll see the workgroup’s name.

Now, on the Mac, open System Preferences. Click Network. Click the connection you’re using (like WiFi or Ethernet). Click Advanced. Click WINS.

Now you see the peculiar controls shown here. Type the workgroup name into the box (if indeed it’s not already a choice in the Workgroup pop-up menu). Click OK, and then click Apply.

Now your Windows PCs show up in the Sidebar, like magic.

Still having trouble? Open System Preferences→Security→Firewall. Make sure your Mac’s firewall is either turned off or at least not set to “Block all incoming connections.”

NOTE

In Windows XP Pro, the next step won’t work unless you turn off Simple File Sharing. To do that, choose Tools→Folder Options in any Explorer window. Click the View tab and turn off “Use simple file sharing.”

4. Click Connect As.

This button appears in the top-right corner of the Finder window; you can see it at bottom in Figure 15-13. Now you’re asked for your name and password (Figure 15-14, top).

NOTE

In Windows 8 and 8.1, there are two ways to log into a computer—two kinds of user accounts. You can sign in with a Microsoft ID (which is just like an Apple ID) or with a regular local account. (Microsoft pushes you very hard to use a Microsoft ID; many features of Windows 8 won’t work without it.)

If you’re trying to connect to a Windows 8/8.1 account with a Microsoft ID, be sure to use that as the account name in this step (it looks like an email address), along with the corresponding password. If you enter the account’s human name, you won’t be able to connect.

Figure 15-14. Top: The PC wants to make sure you’re authorized to visit it. Fortunately, you see this box only the very first time you access a certain Windows folder or disk; after that, you see only the box shown below. Bottom: Here’s the list of shared folders on the PC. Choose the one you want to connect to, and then click OK. Like magic, the Windows folder shows up on your Mac screen, ready to use!

5. Enter the name and password for your account on the PC, and then click OK.

At long last, the contents of the shared folder on the Windows machine appear in your Finder window, just as though you’d tapped into another Mac (Figure 15-14, bottom). The icon of the shared folder appears on your desktop, too, and an Eject button (![]() ) appears next to the PC’s name in your Sidebar.

) appears next to the PC’s name in your Sidebar.

From here, it’s a simple matter to drag files between the machines, to open Word documents on the PC using Word for the Mac, and so on—exactly like you’re hooked into another Mac.

Seated at the PC, Seeing the Mac

Cross-platformers, rejoice: OS X lets you share files in both directions. Not only can your Mac see other PCs on the network, but they can see the Mac, too.

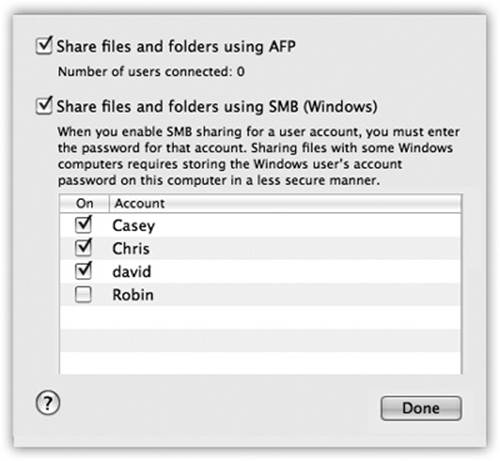

On the Mac, open ![]() →System Preferences→Sharing. Click File Sharing (make sure File Sharing is turned on), and then click Options to open the dialog box shown in Figure 15-14.

→System Preferences→Sharing. Click File Sharing (make sure File Sharing is turned on), and then click Options to open the dialog box shown in Figure 15-14.

Turn on “Share files and folders using SMB (Windows)” (Figure 15-15). Below that checkbox, you see a list of all the accounts on your Mac. Turn on the checkboxes to specify which Mac user accounts you want to be able to access. You must type in each person’s password, too. Click Done.

Figure 15-15. Prepare your Mac for visitation by the Windows PC. It won’t hurt a bit. The system-wide On switch for invasion from Windows is the second checkbox shown here, in the System Preferences→Sharing→File Sharing→Options box. Next, turn on the individual accounts of people you want to allow to connect from the PC. You’ll be asked to enter their account passwords, too. Click Done when you’re done.

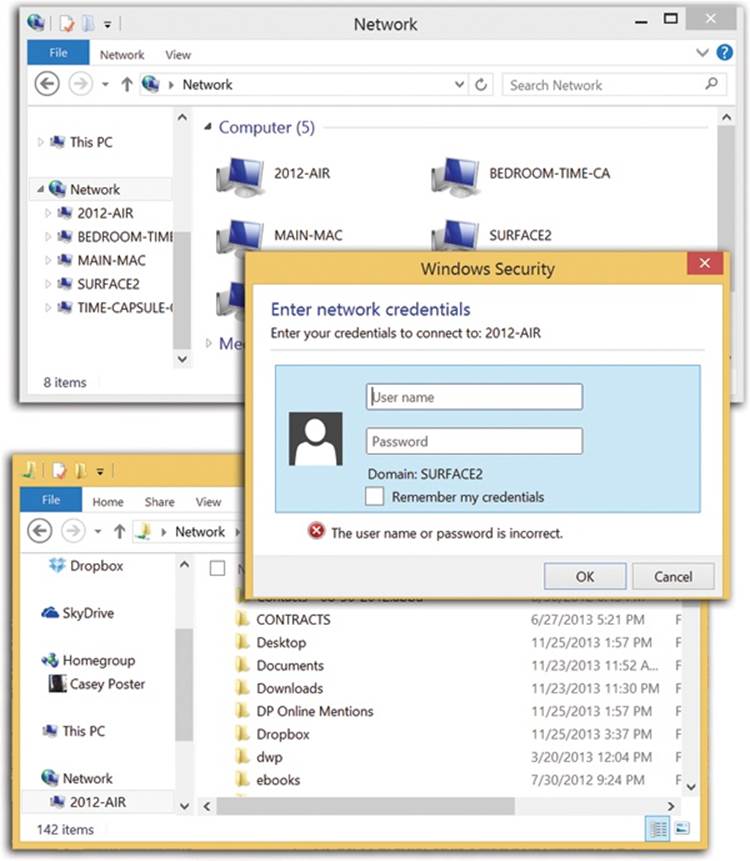

Now, on Windows XP, open My Network Places; in Windows Vista, choose Start→Network; in Windows 7 or 8/8.1, expand the Network heading in the sidebar of any desktop window. If you’ve sacrificed the proper animals to the networking gods, your Mac’s icon should appear in the network window, as shown in Figure 15-16, top.

Figure 15-16. Top: Double-click the Mac you want to visit from your PC (Windows 8.1 is shown here). Middle: Type your Mac’s name and password. (If you’re using Vista or earlier, it’s more complicated. Enter your Mac’s NetBIOS name in all capitals, or its IP address, then a backslash, and then your Mac account short name. You can find out your Mac’s NetBIOS name—what Windows calls it—on the Network pane of System Preferences. Click Advanced, then WINS.) Turn on “Remember my password” if you plan to do this again someday. Click OK. Bottom: Here’s your Mac Home folder—in Windows! Open it up to find all your stuff.

Double-click the Mac’s icon. Public-folder stuff is available immediately. Otherwise, you have to sign in with your Mac account name and password; Figure 15-16, middle, has the details.

In the final window, you see your actual Home folder—on a Windows PC! You’re ready to open its files, copy them back and forth, or whatever (Figure 15-16, bottom).

More Mac-Windows Connections

The direct Mac-to-Windows file-sharing feature of OS X is by far the easiest way to access each other’s files. But it’s not the only way. Chapter 5 offers a long list of other options, from flash drives to the third-party service Dropbox.

Screen Sharing

OS X has answered the prayers of baffled beginners and exasperated experts everywhere. Now, when a novice needs help from a guru, the guru doesn’t have to run all the way downstairs or down the hall to assist. Thanks to OS X’s screen-sharing feature, you can see exactly what’s on the screen of another Mac, from across the network—and even seize control of the other Mac’s mouse and keyboard (with the newbie’s permission, of course).

(Anyone who’s ever tried to help someone troubleshoot over the phone knows exactly how helpful this is. If you haven’t, this small example may suffice: “OK, open the Apple menu and choose ‘About This Mac.’” Pause. “What’s the Apple menu?”)

Screen sharing is also great for collaborating on a document, showing something for approval, or just freaking each other out. It can also be handy when you are the owner of both Macs (a laptop and a desktop, for example), and you want to run a program that you don’t have on the Mac that’s in front of you. For example, you might want to adjust the playlist selection on the upstairs Mac that’s connected to your sound system.

The controlling person can do everything on the controlled Mac, including running programs, messing around with the folders and files, and even shutting it down. You can even press keystrokes on your Mac—⌘-Tab, ⌘-space, ⌘-Option-Escape, and so on—to trigger the corresponding functions on the other Mac.

OS X is crawling with ways to use screen sharing. You can do it over a network, over the Internet, and even during a Messages chat.

Truth is, the Messages method, described in Chapter 13, is much simpler and better than the small-network method described here. It doesn’t require names or passwords, it doesn’t require the same OS X version on both Macs, it’s easy to flip back between seeing the other guy’s screen and your own, and you can transfer files by dragging them from your screen to the other guy’s (or vice versa).

Then again, the small-network method described here is built right into the Finder and doesn’t require logging into Messages.

In modern OS X screen sharing, you can log into a distant Mac and control it as though you were logged into your own account—while somebody else is using it and seeing a totally different screen! Read on.

Other Mac: Give Permission in Advance

As always, trying to understand meta concepts like seeing one Mac’s screen on the monitor of another can get confusing fast. So in this example, suppose that you’re seated at Your Mac, and you want to control Other Mac.

Now, it would be a chaotic world if any Mac could randomly take control of any other Mac (although it sure would be fun). Fortunately, though, nobody can share your screen or take control of your Mac without your explicit permission.

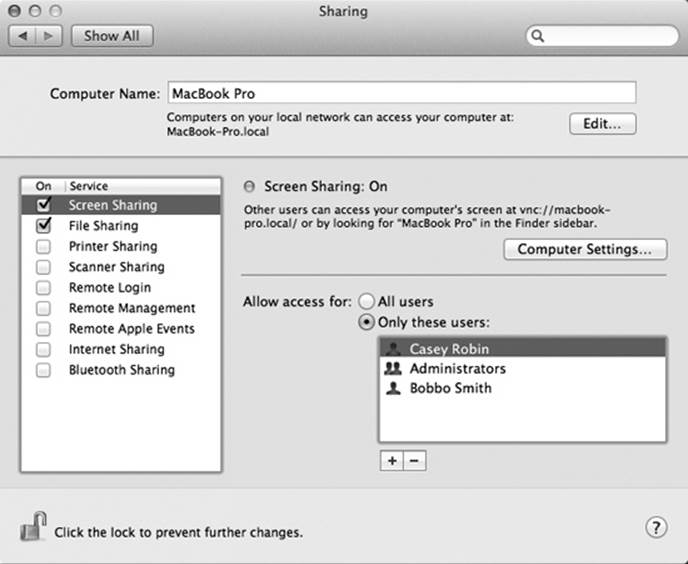

To give such permission, sit down at Other Mac. Choose ![]() →System Preferences→Sharing, and then turn on Screen Sharing.

→System Preferences→Sharing, and then turn on Screen Sharing.

At this point, there are three levels of security to protect your Mac against unauthorized remote-control mischief:

§ Secure. If you select All Users, then anyone with an account on your Mac will be able to tap in and take control anytime they like, even when you’re not around. They’ll just have to enter the same name and password they’d use if they were sitting in front of your machine.

If “anyone” means “you and your spouse” or “you and the other two fourth-grade teachers,” then that’s probably perfectly fine.

§ Securer. For greater security, though, you can limit who’s allowed to stop in. Click “Only these users” and then click the ![]() sign. A small panel appears, listing everyone with an account on your Mac. Choose the ones you trust not to mess things up while you’re away from your Mac (Figure 15-17).

sign. A small panel appears, listing everyone with an account on your Mac. Choose the ones you trust not to mess things up while you’re away from your Mac (Figure 15-17).

TIP

You can permit people to see your Mac’s screen remotely by entering their Apple ID and passwords. That’s a lot simpler and takes less disk space than before, when each person had to have a full-blown account on your Mac, complete with Pictures folder, Movies folder, and so on. To set this up, see the box on Logging In with an Apple ID.

Figure 15-17. Your Mac is now ready to be observed and even controlled by other machines across the network. The people listed here are allowed to tap in anytime they like, even when you’re not at your machine.

§ Securest. If you click “Only these users” and then don’t add anyone to the list, then only people who have Administrator accounts on your Mac (Administrator accounts) can tap into your screen.

Alternatively, if you’re only a little bit of a Scrooge, you can set things up so that they can request permission to share your screen—as long as you’re sitting in front of your Mac at the time and feeling generous.

To set this up, click Computer Settings and then turn on “Anyone may request permission to share screen.” Now your fans will have to request permission to enter, and you’ll have to grant it (by clicking OK on the screen), in real time, while you’re there to watch what they’re doing.

Your Mac: Take Control

All right, Other Mac has been prepared for invasion. Now suppose you’re the person on the other end. You’re the guru, or the parent, or whoever wants to take control.

Sit at Your Mac elsewhere on your home or office network, and proceed like this:

1. Open a Finder window. Expand the Shared list in the Sidebar, if necessary, so that you see the icon of Other Mac. Click it.

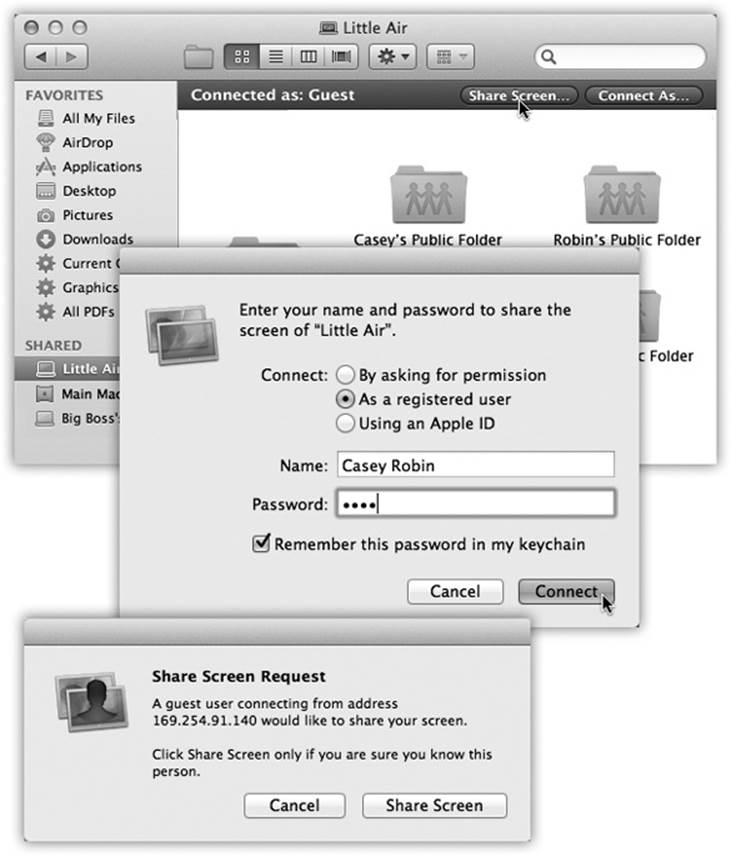

The dark strip at the top of the main window displays a button that wasn’t there before: Share Screen (Figure 15-18, top).

GEM IN THE ROUGH: LOGGING IN WITH AN APPLE ID

In the bad old days, you couldn’t share your screen or your files with other people unless you first created full-blown accounts for them on your Mac. You know: a Home folder, Music and Movies folders, and so on.

Nowadays, you can create a Sharing Only account for them. They can now share your screen or your files without actually having a presence on your hard drive.

In fact, there’s even a third option: They can exploit your shared screen or shared folders just by logging in with their Apple IDs. This way, you don’t even have to set up a name and password for them on your Mac, and they don’t have to learn another name and password. They don’t have an account on your Mac at all—just a Contacts card.

To set this up, open Contacts. Make sure there’s a card in there for the person who will be visiting your Mac over the network. Make sure, furthermore, that the card includes the email address that person uses as an Apple ID.

Now visit System Preferences→Sharing. Click Screen Sharing. As shown in Figure 15-17, click the ![]() sign. In the panel that appears, click Contacts, and double-click the name of the prospective visitor. You’re asked to enter a screen-sharing password for this person (twice) and then click Create Account.

sign. In the panel that appears, click Contacts, and double-click the name of the prospective visitor. You’re asked to enter a screen-sharing password for this person (twice) and then click Create Account.

The visitor should make sure he’s registered his Apple ID in his own account details for System Preferences→Users & Groups.

If so, then the setup is ready. When he attempts to connect to your Mac, he’ll be able to use the “Using an Apple ID” option as his credentials. No account on your Mac is necessary!

2. Click Share Screen.

Now you see the box shown at middle in Figure 15-18. It offers as many as three different ways for you to prove that you’re not some German teenage hacker. “By asking for permission” sends the other Mac’s current operator a message asking if it’s OK for you to take over.

Figure 15-18. Top: Start by clicking Share Screen in the strip at the top of your Mac’s window. Middle: If you’ve been pre-added to the VIP list of authorized screen sharers, as already described, you can sign in with either your account name and password or your Apple ID. If not, you can request permission to share Other Mac’s screen (provided the Mac owner has turned on that option in System Preferences→Sharing→Screen Sharing→Computer Settings). You’ll be granted permission only if Other Mac’s owner happens to be sitting in front of it at the moment and has opted to accept such requests. Bottom: If you request permission, the other person (sitting at Other Mac) sees your request like this.

Most of the time, people choose “As a registered user,” meaning “I have a regular account on the Other Mac.”

But the “Using an Apple ID” option lets you enter an Apple ID and password instead, so the Other Mac’s owner doesn’t have to set up an account for you just so you can use screen sharing or file sharing. See the box on Logging In with an Apple ID.

TIP

In theory, you can also connect from across the Internet, assuming you left your Mac at home turned on and connected to a broadband modem, and assuming you’ve worked through the port-forwarding issue described on Screen sharing with Back to My Mac.

In this case, though, you’d begin by choosing Go→Connect to Server in the Finder; in the Connect to Server box, type in vnc://123.456.78.90 (or whatever your home Mac’s public IP address is). The rest of the steps are the same.

3. If you have a user account on Other Mac, click “As a registered user” and log in. If your Apple ID will suffice, then click “Using an Apple ID” and supply your sharing password.

Your Mac, of course, knows your Apple ID already (because you’ve entered it in your account screen in System Preferences→User Accounts). It shows up here in the dialog box; all you have to do is enter your password.

4. Click Connect.

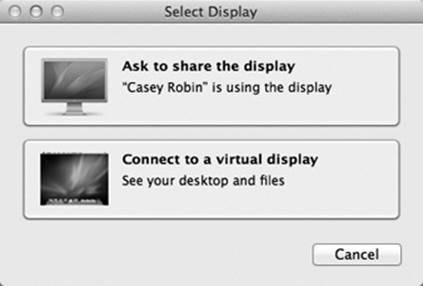

If you’ve signed in successfully, or if permission is granted, then you see the dialog box shown in Figure 15-19. If you choose “Connect to a virtual display,” then you can use your account on the Other Mac even while somebody else is using her account. Simultaneously. Crazy stuff.

Figure 15-19. The Mac wants to know if you want to view or control the screen that’s in use right now by whoever’s using Other Mac—or if you want to use the new “virtual display” option, where you take control of your account on the other Mac without disturbing the totally different activity of whomever is seated there.

(The only evidence she’ll have that you’re rooting around behind the scenes is a tiny menu-bar icon that looks like this: ![]() .)

.)

NOTE

If nobody is using Other Mac at the moment, then it doesn’t matter which option you click. And if you enter the name and password of the person who’s already logged in at Other Mac, then you don’t see the dialog box in Figure 15-19. You just jump right into screen sharing, as shown in Figure 15-20.

5. Click either “Ask to share the display” (to see the same thing as the Other Mac person) or “Connect to a virtual display” (to log into a different account and work independently).

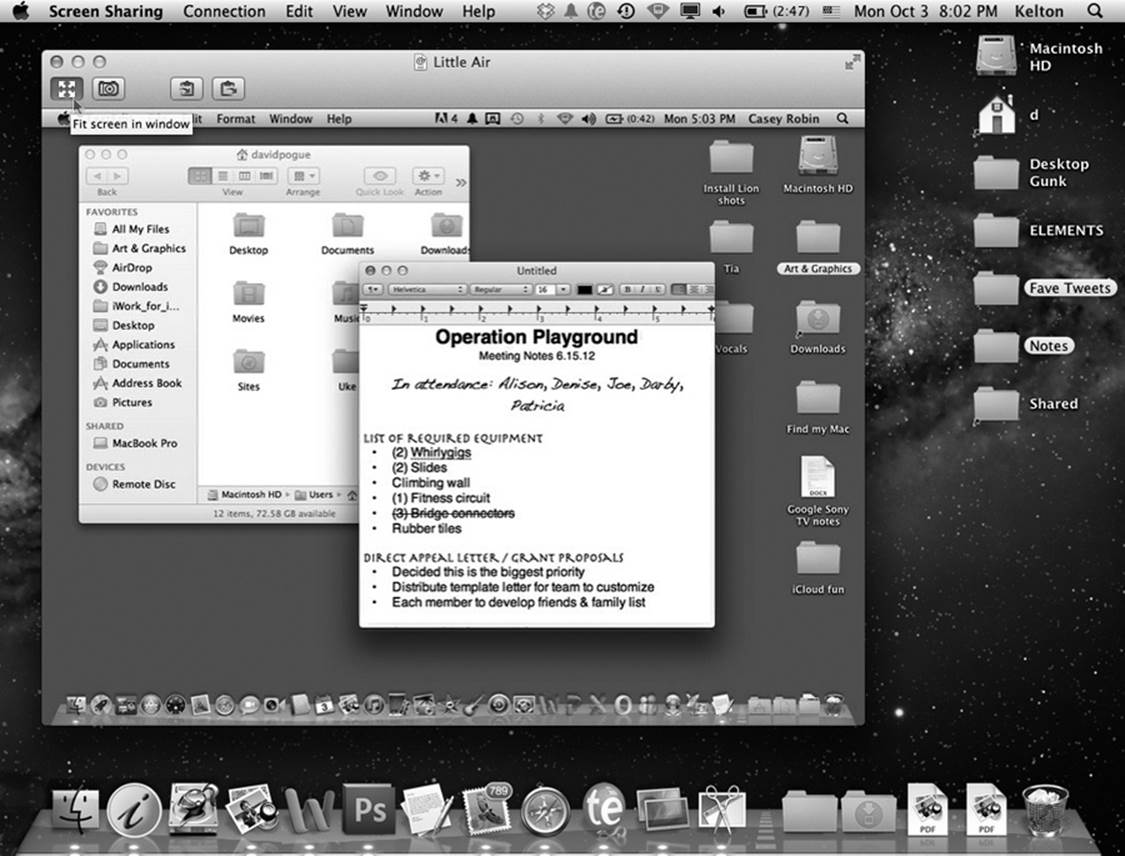

And now a weird and wonderful sight appears. As shown in Figure 15-20, your screen now fills with a second screen—from the other Mac. You have full keyboard and mouse control to work with that other machine exactly as though you were sitting in front of it.

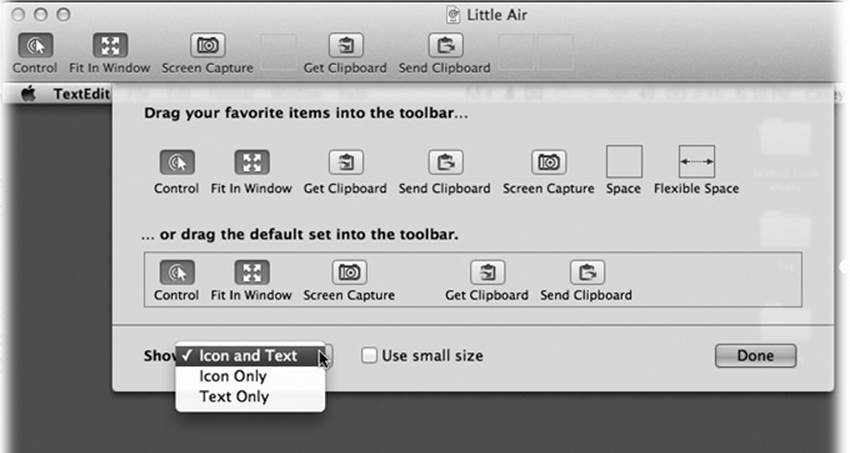

Figure 15-20. Don’t be alarmed. You’re looking at the Other Mac’s desktop in a window on your Mac desktop. You have keyboard and mouse control, and so does the other guy (if he’s there); when you’re really bored, you can play King of the Cursor. (Note the Screen Sharing toolbar, which has been made visible by choosing View→Show Toolbar.)

Well, maybe not exactly. There are a few caveats and options.

§ Full Screen mode. There it is, in the upper-right corner: the ![]() button. If you click it, then your view of Other Mac expands to fill your screen, edge to edge; now there’s no sign at all that you’re actually using a different computer.

button. If you click it, then your view of Other Mac expands to fill your screen, edge to edge; now there’s no sign at all that you’re actually using a different computer.

§ The speed-vs.-blurriness issue. Remember, you’re asking Other Mac to pump its video display across the network—and that takes time. Entire milliseconds, in fact.

So ordinarily, the Mac uses something called adaptive quality, which just means that the screen gets blurry when you scroll, quit a program, or do anything else that creates a sudden change in the picture. You can turn off this feature by choosing View→Full Quality. Now you get full sharpness all the time—but things take longer to scroll, appear, and disappear.

§ Mismatched screen sizes. If the other screen is smaller than yours, no big deal. It floats at actual size on your monitor, with room to spare. But if it’s the same size as yours or larger, then Other Mac’s screen gets shrunk down to fit in a window.

If you’d prefer to see it at actual size, choose View→Turn Scaling Off. Of course, now you have to scroll in the Screen Sharing window to see the whole image.

TIP

Another way to turn scaling on and off is to click the “Fit screen in window” button on the Screen Sharing toolbar (identified in Figure 15-20).

§ Observe Only. In Observe Only mode, your cursor turns white, and you give up all your typing and clicking powers. In other words, you’re playing “Look but don’t touch.” (To enter this mode, choose View→Switch to Observe Mode, or click the corresponding toolbar icon.)

This is a handy option when the person at Other Mac just wants to give you a slideshow or a presentation, or when you just want to watch what he’s doing when you’re on a troubleshooting hunt.

§ Manage the Clipboard. You can actually copy and paste material from the remote-controlled Mac to your own—or the other way—thanks to a freaky little wormhole in the time-space continuum. In the Edit menu, choose Send Clipboard to put what’s on your Clipboard onto OtherMac’s Clipboard, or Get Clipboard to copy Other Mac’s Clipboard contents onto your Clipboard. Breathe slowly and drink plenty of fluids, and your brain won’t explode. (There are toolbar-button equivalents, too.)

§ Dragging files between computers. You can now transfer files from one Mac to the other, just by dragging their icons. Drag the icon from the distant Mac clear out of its window, and pause over your own desktop until your cursor sprouts a green ![]() icon. When you let go, the files get copied to your own Mac.

icon. When you let go, the files get copied to your own Mac.

GEM IN THE ROUGH: SCREEN SHARING WITH WINDOWS

The beauty of Apple’s screen-sharing technology is that it isn’t Apple’s screen-sharing technology. It’s a popular open standard called VNC (Virtual Network Computing).

Once you’ve turned on Screen Sharing on your Mac, any computer on earth with a free VNC client program—sort of a viewer program—can pop onto your machine for a screen share. VNC clients are available for Windows, Linux, pre-Leopard Macs, and even some cellphones. (Not all VNC programs work with the Mavericks version of screen sharing, alas; some require updates.)