High Performance MySQL (2012)

Chapter 14. Application-Level Optimization

If you spend a lot of time improving MySQL’s performance, it’s easy to get tunnel vision and forget to focus on the user’s experience. You may step back for a bit and realize that MySQL is so highly optimized that it’s contributing only a tiny fraction of the response time the user sees, and it’s time to focus elsewhere. This is a great insight (especially for a DBA), and it’s exactly the right thing to do. But what is causing problems, if not MySQL? The answer can be found most reliably and quickly by measuring, using the techniques we showed in Chapter 3. If your profiling is thorough and you follow a logical process, it should not be hard to find the source of your problem. Sometimes, though, even when the problem is MySQL, it might be easiest to solve it in another part of the system!

No matter where the problem lies, there’s sure to be at least one great tool available to help you measure it, often for free. For example, if you have issues with JavaScript or page rendering, you can use the profiler included with the Firebug extension for the Firefox web browser, or you can use the YSlow tool from Yahoo!. We mentioned several application-level tools in Chapter 3. Some tools even profile the whole stack; New Relic is an example of a tool that profiles the frontend, application, and backend of web applications.

Common Problems

We see the same problems over and over again in applications, often because people have used poorly designed off-the-shelf systems or popular frameworks that simplify development. Although it’s sometimes easier and faster to use something you didn’t build yourself, it also adds risk if you don’t really know what it’s doing under the hood. Here’s a laundry list of things that we often find to be problems, to stimulate your creative thought processes:

§ What’s using the CPU, disk, network, and memory resources on each of the machines involved? Do the numbers look reasonable to you? If not, check the basics for the applications that are hogging resources. Configuration is sometimes the simplest way to solve problems. For example, if Apache runs out of memory because it creates 1,000 worker processes that each need 50 MB of memory, you can configure the application to require fewer Apache workers. You can also configure the system to use less memory for each process.

§ Is the application really using all the data it’s getting? Fetching 1,000 rows but displaying only 10 and throwing away the rest is a common mistake. (However, if the application caches the other 990 rows for later use, it might be an intentional optimization.)

§ Is the application doing processing that ought to be done in the database, or vice versa? Two examples are fetching all rows from a table to count them and doing complex string manipulations in the database. Databases are good at counting rows, and application languages are good at regular expressions. Use the best tool for the job.

§ Is the application doing too many queries? Object-relational mapping (ORM) query interfaces that “protect programmers from having to write SQL” are often to blame. The database server is designed to match data from multiple tables. Remove the nested loops in the code and write a join instead.

§ Is the application doing too few queries? We know, we just said doing too many queries can be a problem. But sometimes “manual joins” and similar practices can be a good idea, because they can permit more granular and efficient caching, less locking, and sometimes even faster execution when you emulate a hash join in application code (MySQL’s nested loop join method is not always efficient).

§ Is the application connecting to MySQL unnecessarily? If you can get the data from the cache, don’t connect.

§ Is the application connecting too many times to the same MySQL instance, perhaps because different parts of the application open their own connections? It’s usually a better idea to reuse the same connection throughout.

§ Is the application doing a lot of “garbage” queries? A common example is sending a ping to see if the server is alive before sending the query itself, or selecting the desired database before each query. It might be a good idea to always connect to a specific database and use fully qualified names for tables. (This also makes it easier to analyze queries from the log or via SHOW PROCESSLIST, because you can execute them without needing to change the database.) “Preparing” the connection is another common problem. The Java driver in particular does a lot of things during preparation, most of which you can disable. Another common garbage query is SET NAMES UTF8, which is the wrong way to do things anyway (it does not change the client library’s character set; it affects only the server). If your application uses a specific character set for most of its work, you can avoid the need to change the character set by configuring it as the default.

§ Does the application use a connection pool? This can be both a good and a bad thing. It helps limit the number of connections, which is good when connections aren’t used for many queries (Ajax applications are a typical example). However, it can have side effects, such as applications interfering with each other’s transactions, temporary tables, connection-specific settings, and user-defined variables.

§ Does the application use persistent connections? These can result in way too many connections to MySQL. They’re generally a bad idea, except if the cost of connecting to MySQL is very high because of a slow network, if the connection will be used only for one or two fast queries, or if you’re connecting so frequently that you’re running out of local port numbers on the client. If you configure MySQL correctly, you might not need persistent connections. Use skip-name-resolve to prevent reverse DNS lookups, ensure that thread_cache is set high enough, and increase back_log. See Chapter 8 and Chapter 9 for more details.

§ Is the application holding connections open even when it’s not using them? If so—particularly if it connects to many servers—it might be consuming connections that other processes need. For example, suppose you’re connecting to 10 MySQL servers. Getting 10 connections from an Apache process isn’t a problem, but only one of them will really be doing anything at any given time. The other nine will spend a lot of time in the Sleep state. If one server slows down, or there’s a long network call, the other servers can suffer because they’re out of connections. The solution is to control how the application uses connections. For example, you can batch operations to each MySQL instance in turn, and close each connection before querying the next one. If you’re doing time-consuming operations, such as calls to a web service, you can even close the MySQL connection, perform the time-consuming work, then reopen the MySQL connection and continue working with the database.

The difference between persistent connections and connection pooling can be confusing. Persistent connections can cause the same side effects as connection pooling, because a reused connection is stateful in either case.

However, connection pools don’t usually result in as many connections to the server, because they queue and share connections among processes. Persistent connections, on the other hand, are created on a per-process basis and can’t be shared among processes.

Connection pools also allow more control over connection policies than shared connections. You can configure a pool to autoextend, but the usual practice is to queue connection requests when the pool is completely busy. This makes the connection requests wait on the application server, rather than overload the MySQL server with too many connections.

There are many ways to make queries and connections faster, but the general rule is that avoiding them altogether is better than trying to speed them up.

Web Server Issues

Apache is the most popular server software for web applications. It works well for many purposes, but when used badly it can consume a lot of resources. The most common issues are keeping its processes alive too long, and using it for a mixture of purposes instead of optimizing it separately for each type of work.

Apache is usually used with mod_php, mod_perl, and mod_python in a “prefork” configuration. Preforking dedicates a process for each request. Because the PHP, Perl, and Python scripts can be demanding, it’s not uncommon for each process to use 50 or 100 MB of memory. When a request completes, it returns most of this memory to the operating system, but not all of it. Apache keeps the process open and reuses it for future requests. This means that if the next request is for a static file, such as a CSS file or an image, you’ll wind up with a big fat process serving a simple request. This is why it’s dangerous to use Apache as a general-purpose web server. It is general-purpose, but if you specialize it, you’ll get much better performance.

The other major problem is that processes can be kept busy for a long time if you have Keep-Alive enabled. And even if you don’t, some of the processes might be staying alive too long, “spoon-feeding” content to a client that is fetching the data slowly.[208]

People also often make the mistake of leaving the default set of Apache modules enabled. You can trim Apache’s footprint by removing modules you don’t need. It’s simple: just review the Apache configuration file and comment out unwanted modules, then restart Apache. You can also remove unused PHP modules from your php.ini file.

The bottom line is that if you create an all-purpose Apache configuration that faces the Web directly, you’re likely to end up with many heavyweight Apache processes. These will waste resources on your web server. They can also keep a lot of connections open to MySQL, wasting resources on MySQL, too. Here are some ways you can reduce the load on your servers:[209]

§ Don’t use Apache to serve static content, or at least use a different Apache instance. Popular alternatives are Nginx (http://www.nginx.com) and lighttpd (http://www.lighttpd.net).

§ Use a caching proxy server, such as Squid or Varnish, to keep requests from ever reaching your web servers. Even if you can’t cache full pages on this level, you might be able to cache most of a page and use technologies such as edge side includes (ESI; see http://www.esi.org) to embed the small dynamic portion of the page into the cached static portion.

§ Set an expiration policy on both dynamic and static content. You can use caching proxies such as Squid to invalidate content explicitly. Wikipedia uses this technique to remove articles from caches when they change.

§ Sometimes you might need to change the application so that you can use longer expiration times. For example, if you tell the browser to cache CSS and JavaScript files forever and then release a change to the site’s HTML, the pages might render badly. You can version the files explicitly with a unique filename for each revision. For example, you can customize your website publishing script to copy the CSS files to /css/123_frontpage.css, where 123 is the Subversion revision number. You can do the same thing for image filenames—never reuse a filename, and your pages will never break when you upgrade them, no matter how long the browser caches them.

§ Don’t let Apache spoon-feed the client. It’s not just slow; it also makes denial-of-service attacks easy. Hardware load balancers typically do buffering, so Apache can finish quickly and the load balancer can spoon-feed the client from the buffer. You can also use Nginx, Squid, or Apache in event-driven mode in front of the application.

§ Enable gzip compression. It’s very cheap for modern CPUs, and it saves a lot of traffic. If you want to save on CPU cycles, you can cache and serve the compressed version of the page with a lightweight server such as Nginx.

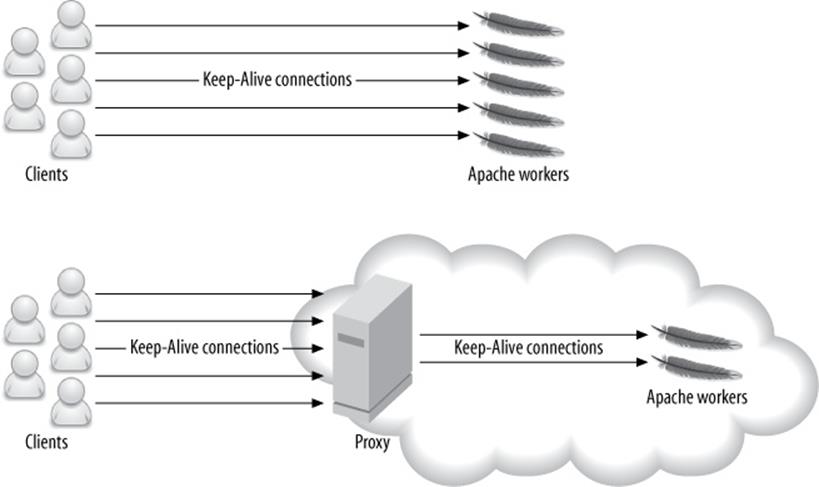

§ Don’t configure Apache with a Keep-Alive for long-distance connections, because that will keep fat Apache processes alive for a long time. Instead, let a server-side proxy handle the Keep-Alive, and shield Apache from the client. It’s OK to configure the connections between the proxy and Apache with a Keep-Alive, because the proxy will use only a few connections to fetch data from Apache. Figure 14-1 illustrates the difference.

Figure 14-1. A proxy can shield Apache from long-lived Keep-Alive connections, resulting in fewer Apache workers

These tactics should keep Apache processes short-lived, so you don’t end up with more processes than you need. However, some operations might still cause an Apache process to stay alive for a long time and consume a lot of resources. An example is a query to an external resource that has high latency, such as a remote web service. This problem is often unsolvable.

Finding the Optimal Concurrency

Every web server has an optimal concurrency—that is, an optimal number of concurrent connections that will result in requests being processed as quickly as possible, without overloading your systems. This is the maximum system capacity we referred to in Chapter 11. A little measurement and modeling, or simply trial and error, can be required to find this “magic number,” but it’s worth the effort.

It’s common for a high-traffic website to handle thousands of connections to the web server at the same time. However, only a few of these connections need to be actively processing requests. The others might be reading requests, handling file uploads, spoon-feeding content, or simply awaiting further requests from the client.

As concurrency increases, there’s a point at which the server reaches its peak throughput. After that, the throughput levels off and often starts to decrease. More importantly, the response time (latency) starts to increase due to queueing.

To see why, consider what happens when you have a single CPU and the server receives 100 requests simultaneously. Imagine that one second of CPU time is required to process each request. Assuming a perfect operating system scheduler with no overhead, and no context switching overhead, the requests will need a total of 100 CPU seconds to complete.

What’s the best way to serve the requests? You can queue them one after another, or you can run them in parallel and switch between them, giving each request equal time before switching to the next. In both cases, the throughput is one request per second. However, the average latency is 50 seconds if they’re queued (concurrency = 1), and 100 seconds if they’re run in parallel (concurrency = 100). In practice, the average latency would be even higher for parallel execution, because of the switching cost.

For a CPU-bound workload, the optimal concurrency is equal to the number of CPUs (or CPU cores). However, processes are not always runnable, because they make blocking calls such as I/O, database queries, and network requests. Therefore, the optimal concurrency is usually higher than the number of CPUs.

You can estimate the optimal concurrency, but it requires accurate profiling. It’s usually easier to either experiment with different concurrency values and see what gives the peak throughput without degrading response time, or measure your real workload and analyze it. Percona Toolkit’s pt-tcp-model tool can help you measure and model your system’s scalability and performance characteristics from a TCP dump.

[208] Spoon-feeding occurs when a client makes an HTTP request but then doesn’t fetch the result quickly. Until the client fetches the entire result, the HTTP connection—and thus the Apache process—stays alive.

[209] A good book on how to optimize web applications is High Performance Web Sites by Steve Souders (O’Reilly). Though it’s mostly about how to make websites faster from the client’s point of view, the practices he advocates are good for your servers, too. Steve’s follow-up book, Even Faster Web Sites, is also a good resource.

Caching

Caching is vital for high-load applications. A typical web application serves a lot of content that costs much more to generate than it costs to cache (including the cost of checking and expiring the cache), so caching can usually improve performance by orders of magnitude. The trick is to find the right combination of granularity and expiration policies. You also need to decide what content to cache and where to cache it.

A typical high-load application has many layers of caching. Caching doesn’t just happen in your servers: it happens at every step along the way, including the user’s web browser (that’s what content expiration headers are for). In general, the closer the cache is to the client, the more resources it saves and the more effective it is. Serving an image from the browser’s cache is better than serving it from the web server’s memory, which is better than reading it from the server’s disk. Each type of cache has unique characteristics, such as size and latency; we examine some of them in the following sections.

You can think about caches in two broad categories: passive caches and active caches. Passive caches do nothing but store and return data. When you request something from a passive cache, either you get the result or the cache tells you “that doesn’t exist.” An example of a passive cache ismemcached.

In contrast, an active cache does something when there’s a miss. It usually passes your request on to some other part of the application, which generates the requested result. The active cache then stores the result and returns it. The Squid caching proxy server is an active cache.

When you design your application, you usually want your caches to be active (also called transparent), because they hide the check-generate-store logic from the application. You can build active caches on top of passive caches.

Caching Below the Application

The MySQL server has its own internal caches, and you can build your own cache and summary tables, too. You can custom-design your cache tables so that they’re most useful for filtering, sorting, joining to other tables, counting, or any other purpose. Cache tables are also more persistent than many application-level caches, because they’ll survive a server restart.

We wrote about these cache strategies in Chapter 4 and Chapter 5, so in this chapter we focus on caching at the application level and above.

CACHING DOESN’T ALWAYS HELP

You need to make sure that caching really improves performance, because it might not help at all. For example, in practice it’s often faster to serve content from Nginx’s memory than to serve it from a caching proxy. This is especially true if the proxy’s cache is on disk.

The reason is simple: caching has its own overhead. There’s the overhead of checking the cache, and serving the data from the cache if there’s a hit. There’s also the overhead of invalidating the cache and storing data in it. Caching is helpful only if these costs are less than the cost of generating and serving the data without a cache.

If you know the costs of all these operations, you can calculate how much the cache helps. The cost without the cache is the cost of generating the data for each request. The cost with the cache is the cost of checking the cache, plus the probability of a cache miss times the cost of generating the data, plus the probability of a cache hit times the cost of serving the data from the cache.

If the cost with the cache is lower than without, it’s an improvement, but that’s not guaranteed. Also bear in mind that, as in the case of serving data from Nginx’s memory rather than from the proxy’s on-disk cache, some caches are cheaper than others.

Application-Level Caching

An application-level cache typically stores data in memory on the same machine, or across the network in another machine’s memory.

Application-level caching can be more efficient than caching at a lower level, because the application can store partially computed results in the cache. Thus, the cache saves two types of work: fetching the data, and doing computations on it. A good example is blocks of HTML text. The application can generate HTML snippets, such as the top news headlines, and cache them. Subsequent page views can then simply insert this cached text into the page. In general, the more you process the data before you cache it, the more work you save when there’s a cache hit.

The disadvantage is that the cache hit rate can be lower, and the cache can use more memory. Suppose you need 50 different versions of the top news headlines, so the user sees different content depending on where she lives. You’ll need enough memory to store all 50 of them, fewer requests will hit any given version of the headlines, and invalidation can be more complicated.

There are many types of application caches. Here are a few:

Local caches

These caches are usually small and live only in the process’s memory for the duration of the request. They’re useful for avoiding a repeated request for a resource when it’s needed more than once. There’s nothing fancy about this type of cache: it’s usually just a variable or hash table in the application code. For example, suppose you need to display a user’s name, and you know the user’s ID. You can build a get_name_from_id() function and add caching to it like this:

<?php

function get_name_from_id($user_id) {

static $name; // static makes the variable persist

if ( !$name ) {

// Fetch name from database

}

return $name;

}

?>

If you’re using Perl, the Memoize module is the standard way to cache the results of function calls:

use Memoize qw(memoize);

memoize 'get_name_from_id';

sub get_name_from_id {

my ( $user_id ) = @_;

my $name = # get name from database

return $name;

}

These techniques are simple, but they can save your application a lot of work.

Local shared-memory caches

These caches are medium-sized (a few GB), fast, and hard to synchronize across multiple machines. They’re good for small, semi-static bits of data. Examples include lists of the cities in each state, the partitioning function (mapping table) for a sharded data store, or data that you can invalidate with time-to-live (TTL) policies. The biggest benefit of shared memory is that accessing it is very fast—usually much faster than accessing any type of remote cache.

Distributed memory caches

The best-known example of a distributed memory cache is memcached. Distributed caches are much larger than local shared-memory caches and are easy to grow. Only one copy of each bit of cached data is created, so you don’t waste memory and introduce consistency problems by caching the same data in many places. Distributed memory is great for storing shared objects, such as user profiles, comments, and HTML snippets.

These caches have much higher latency than local shared-memory caches, though, so the most efficient way to use them is with multiple get operations (i.e., getting many objects in a single round-trip). They also require you to plan how you’ll add more nodes, and what to do if one of the nodes dies. In both cases, the application needs to decide how to distribute or redistribute cached objects across the nodes.

Consistent caching is important to avoid performance problems when you add a server to or remove a server from your cache cluster. There’s a consistent caching library for memcached at http://www.audioscrobbler.net/development/ketama/.

On-disk caches

Disks are slow, so caching on disk is best for persistent objects, objects that are hard to fit in memory, or static content (pregenerated custom images, for example).

One very useful trick with on-disk caches and web servers is to use 404 error handlers to catch cache misses. Suppose your web application shows a custom-generated image in the header, based on the user’s name (“Welcome back, John!”). You can refer to the image as/images/welcomeback/john.jpg. If the image doesn’t exist, it will cause a 404 error and trigger the error handler. The error handler can generate the image, store it on the disk, and either issue a redirect or just stream the image back to the browser. Further requests will just return the image from the file.

You can use this trick for many types of content. For example, instead of caching the latest headlines as a block of HTML, you can store them in a JavaScript file and then refer to /latest_headlines.js in the web page’s header.

Cache invalidation is easy: just delete the file. You can implement TTL invalidation by running a periodic job that deletes files created more than N minutes ago. And if you want to limit the cache size, you can implement a least recently used (LRU) invalidation policy by deleting files in order of their last access time.

Invalidation based on last access time requires you to enable the access time option in your filesystem’s mount options. (You actually do this by omitting the noatime mount option.) If you do this, you should use an in-memory filesystem to avoid a lot of disk activity.

Cache Control Policies

Caches create the same problem as denormalizing your database design: they duplicate data, which means there are multiple places to update the data, and you have to figure out how to avoid reading stale data. The following are several of the most common cache control policies:

TTL (time to live)

The cached object is stored with an expiration date; you can either remove the object with a purge process when that date arrives, or leave it until the next time something accesses it (at which time you should replace it with a fresh version). This invalidation policy is best for data that changes rarely or doesn’t have to be fresh.

Explicit invalidation

If stale data is not acceptable, the process that updates the source data can invalidate the old version in the cache. There are two variations of this policy: write-invalidate and write-update. The write-invalidate policy is simple: you just mark the cached data as expired (and optionally purge it from the cache). The write-update policy involves a little more work, because you have to replace the old cache entry with the updated data. However, it can be very beneficial, especially if it is expensive to generate the cached data (which the writer process might already have). If you update the cached data, future requests won’t have to wait for the application to generate it. If you do invalidations in the background, such as TTL-based invalidations, you can generate new versions of the invalidated data in a process that’s completely detached from any user request.

Invalidation on read

Instead of invalidating stale data when you change the source data from which it’s derived, you can store some information that lets you determine whether the data has expired when you read it from the cache. This has a significant advantage over explicit invalidation: it has a fixed cost that you can spread out over time. Suppose you invalidate an object upon which a million cached objects depend. If you invalidate on write, you have to invalidate a million things in the cache in one hit, which could take a long time even if you have an efficient way to find them. If you invalidate on read, the write can complete immediately, and each of a million reads will be delayed slightly. This spreads out the cost of the invalidation and helps avoid spikes of load and long latencies.

One of the simplest ways to do invalidation on read is with object versioning. With this approach, when you store an object in the cache, you also store the current version number or timestamp of the data upon which it depends. For example, suppose you’re caching statistics about a user’s blog posts, including the number of posts the user has made. When you cache the blog_stats object, you store the user’s current version number with it, because the statistics are dependent on the user.

Whenever you update some data that also depends on the user, you update the user’s version number. Suppose the user’s version is initially 0, and you generate and cache the statistics. When the user publishes a blog post, you increase the user’s version to 1 (you’d store this with the blog post too, though we don’t really need it for this example). Then, when you need to display the statistics, you compare the cached blog_stats object’s version to the cached user’s version. Because the user’s version is greater than the object’s version, you know that the statistics are stale and you need to recompute them.

This is a pretty coarse way to invalidate content, because it assumes that every bit of data that’s dependent on the user also interacts with all other data. That’s not always true. If a user edits a blog post, for example, you’ll increment the user’s version, and that will invalidate the stored statistics even though the statistics (the number of blog posts) didn’t really change. The trade-off is simplicity. A simple cache invalidation policy isn’t just easier to build; it might be more efficient, too.

Object versioning is a simplified approach to a tagged cache, which can handle more complex dependencies. A tagged cache knows about different kinds of dependencies and tracks versions separately for each of them. To return to the book club example from Chapter 11, you could make the cached comments dependent on the user’s version and the book’s version by tagging the comments with these version numbers: user_ver=1234 and book_ver=5678. If either version changes, you’d refresh the cached comments.

Cache Object Hierarchies

Storing objects in a cache hierarchically can help with retrieval, invalidation, and memory usage. Instead of caching just objects, you can cache the object IDs, as well as the groups of object IDs that you commonly retrieve together.

A search result on an ecommerce website is a good example of this technique. A search might return a list of matching products, complete with names, descriptions, thumbnail photos, and prices. Caching the entire list would be inefficient: other searches would be likely to include some of the same products, resulting in duplicate data and wasted memory. That strategy would also make it hard to find and invalidate search results when a product’s price changes, because you’d have to look inside each list to see which ones include the updated product.

Instead of caching the list, you can cache minimal information about the search, such as the number of results returned and a list of product IDs. You can then cache each product separately. This solves both problems: it doesn’t duplicate any results, and it makes it easy to invalidate the cache at the granularity of individual products.

The drawback is that you have to retrieve multiple objects from the cache, instead of getting the entire search result at once. However, storing the list of product IDs for the search result makes this efficient. Now a cache hit returns the list of IDs, which you can use for a second call to the cache. The second call can return multiple products if the cache lets you get multiple results with a single call (memcached supports this through the mget() call).

If you’re not careful, though, this approach could cause odd results. Suppose you use a TTL policy to invalidate search results, and you invalidate individual products explicitly when they change. Now imagine that a product’s description changes so it no longer contains the keywords that matched a search, but the search isn’t old enough to have expired from the cache. Your users will see stale search results, because the cached search will refer to the product even though it no longer matches the search keywords.

This isn’t usually a problem for most applications. If your application can’t tolerate it, you can use version-based caching and store the product versions with the results when you perform a search. When you find a search result in the cache, you can compare each product’s version in the search results to the current (cached) version. If any product is stale, you can repeat the search and recache the results.

It’s important to understand how expensive a remote cache access is. Although caches are fast and avoid a lot of work, the network round-trip to a cache server on a LAN typically takes about three tenths of a millisecond. We’ve seen many cases where a complex web page requires around a thousand cache accesses to assemble. That’s a total of three seconds of network latency, which means that your page can be unacceptably slow even if it’s served without a single database access! Using a multi-get call to the cache is absolutely vital in these situations. Using a cache hierarchy, with a smaller local cache, can also be very beneficial.

Pregenerating Content

In addition to caching bits of data at the application level, you can prerequest some pages with background processes and store the results as static pages. If your pages are dynamic, you can pregenerate parts of the pages and use a technique such as server-side includes to build the final pages. This can help to reduce the size and cost of the pregenerated content, because you might otherwise duplicate a lot of content due to minor variations in how the constituent pieces are assembled into the final page. You can use a pregeneration strategy for almost any type of caching, includingmemcached.

Pregenerating content has several important benefits:

§ Your application’s code doesn’t have to be complicated with hit and miss paths.

§ It works well when the miss path is unacceptably slow, because it ensures that a miss never happens. In fact, anytime you design any type of caching system, you should always consider how slow the miss path is. If the average performance increases a lot but the occasional request becomes extremely slow due to regenerating cached content, it might actually be worse than not using a cache. Consistent performance is often as important as fast performance.

§ Pregenerating content avoids a stampede to the cache when there’s a miss.

Caching pregenerated content can take a lot of space, and it’s not always possible to pregenerate everything. As with any form of caching, the most important pieces of content to pregenerate are those that are requested the most or are the most expensive to generate, so you can do on-demand generation with the 404 error handlers we mentioned earlier in this chapter.

Pregenerated content sometimes benefits from being stored on an in-memory filesystem to avoid disk I/O.

The Cache as an Infrastructure Component

A cache is likely to become a vital part of your infrastructure. It can be easy to fall into the trap of thinking of a cache as a nice thing to have, but not something so important that you can’t live without it. You might reason that if the cache server goes down, or you lose the cached content, the request will simply go to the database instead. This might be true when you initially add the cache into the application, but the cache can enable the application to grow significantly without increasing the resources dedicated to some portion of the system—typically the database. As a result, you might become dependent on the cache without realizing it.

For example, if your cache hit rate is 90% and you lose the cache for some reason, the load on the database will increase tenfold. It’s rather likely that this will exceed the database server’s capacity.

To avoid surprises such as this, you should think about some kind of high-availability solution for the cache (the data as well as the service), or at least measure the performance impact of disabling the cache or losing its data. You might need to design the application to degrade its functionality, for example.

Using HandlerSocket and memcached Access

Instead of storing data in MySQL and caching it outside of MySQL, an alternative approach is to create a faster access path to MySQL and then bypass the cache. For small, simple queries, a large portion of the overhead can come from parsing the SQL, checking privileges, generating an execution plan, and so on. If this overhead can be eliminated, MySQL can be very fast at simple queries.

There are currently two solutions that take advantage of this by permitting so-called NoSQL access to MySQL. The first is a daemon plugin called HandlerSocket, which was created at DeNA, a large Japanese social networking site. It permits you to access an InnoDB Handler object through a simple protocol. In effect, you’re reaching past the upper layers of the server and connecting directly to InnoDB over the network. There are reports of HandlerSocket achieving over 750,000 queries per second. HandlerSocket is distributed with Percona Server, and the memcached access to InnoDB is available in a lab release of MySQL 5.6.

The second option is accessing InnoDB through the memcached protocol. The lab releases of MySQL 5.6 have a plugin that permits this.

Both approaches are somewhat limited—especially the memcached approach, which doesn’t support as many access methods to the data. Why would you ever want to access your data through anything but SQL? Aside from speed, the biggest reason is probably simplicity. It’s a big win to get rid of caches, and all of the invalidation logic and additional infrastructure that accompanies them.

Extending MySQL

If MySQL can’t do what you need, one possibility is to extend its capabilities. We won’t show you how to do that, but we want to mention some of the possibilities. If you’re interested in exploring any of these avenues further, there are good resources online, and there are books available on many of the topics.

When we say “MySQL can’t do what you need,” we mean two things: MySQL can’t do it at all, or MySQL can do it, but in a slow or awkward way that’s not good enough. Either is a reason to look at extending MySQL. The good news is that MySQL is becoming more and more modular and general-purpose.

Storage engines are a great way to extend MySQL for a special purpose. Brian Aker has written a skeleton storage engine and a series of articles and presentations about how to get started writing your own storage engine. This has formed the basis for several of the major third-party storage engines. Many companies have written their own internal storage engines. For example, some social networking companies use special storage engines for social graph operations, and we know of a company that built a custom engine for fuzzy searches. A simple custom storage engine isn’t very hard to write.

You can also use a storage engine as an interface to another piece of software. A good example of this is the Sphinx storage engine, which interfaces with the Sphinx full-text search software (see Appendix F).

Alternatives to MySQL

MySQL is not necessarily the solution for every need. It’s often much better to do some work completely outside MySQL, even if MySQL can theoretically do what you want.

One of the most obvious examples is storing data in a traditional filesystem instead of in tables. Image files are the classic case: you can put them into a BLOB column, but this is rarely a good idea.[210] The usual practice is to store images or other large binary files on the filesystem and store the filenames inside MySQL; the application can then retrieve the files from outside of MySQL. In a web application, you accomplish this by putting the filename in the <img> element’s src attribute.

Full-text searching is something else that’s best handled outside of MySQL—MySQL doesn’t perform these searches as well as Lucene or Sphinx.

The NDB API can also be useful for certain tasks. For instance, although MySQL’s NDB Cluster storage engine isn’t (yet) well suited for storing all of a high-performance web application’s data, it’s possible to use the NDB API directly for storing website session data or user registration information. You can learn more about the NDB API at http://dev.mysql.com/doc/ndbapi/en/index.html. There’s also an NDB module for Apache, mod_ndb, which you can download at http://code.google.com/p/mod-ndb/.

Finally, for some operations—such as graph relationships and tree traversals—a relational database just isn’t always the right paradigm. MySQL isn’t good for distributed data processing, because it lacks parallel query execution capabilities. You’ll probably want to use other tools for this purpose (possibly in combination with MySQL). Examples that come to mind:

§ We have replaced MySQL with Redis when simple key-value pairs were being stored at such a high rate that the replicas fell behind, even though the master could handle the load just fine. Redis is also popular for queues, due to its nice support for queue operations.

§ Hadoop is the elephant in the room, pun intended. Hybrid MySQL/Hadoop deployments are very common for processing large or semistructured datasets.

[210] There are advantages to using MySQL replication to distribute images quickly to many machines, and we know of some applications that use this technique.

Summary

Optimization isn’t just a database thing. As we suggested in Chapter 3, the highest form of optimization is both business-focused and user-focused. Full-stack performance optimization is what’s really needed to achieve this.

The first thing to do is measure, as always. Focus on profiling per-tier. Which tiers are responsible for most of the response time? Concentrate there first. If the user’s experience is impacted the most by DOM rendering in the browser, and MySQL contributes only a tiny fraction of the total response time, then optimizing queries further can never help the user experience appreciably. After you’ve measured, it’s usually easy to understand where your efforts should be directed. We recommend reading both of Steve Souders’s books (High Performance Web Sites and Even Faster Web Sites) and the use of New Relic.

You can often find big, easy wins in web server configuration and caching. There’s a stereotypical notion that “it’s always a database problem,” but that just isn’t true. The other tiers in the application are no less important, and they’re just as prone to being misconfigured, although sometimes the effects are less obvious. Caches, in particular, can help you deliver a lot of content at a much lower cost than you’d be able to do with MySQL alone. And although Apache is still the world’s most popular web server software, it’s not always the best tool for the job, so consider alternatives such as Nginx when they make sense.

All materials on the site are licensed Creative Commons Attribution-Sharealike 3.0 Unported CC BY-SA 3.0 & GNU Free Documentation License (GFDL)

If you are the copyright holder of any material contained on our site and intend to remove it, please contact our site administrator for approval.

© 2016-2025 All site design rights belong to S.Y.A.