Games, Design and Play: A detailed approach to iterative game design (2016)

Part II: Process

Chapter 6. Design Values

Most simply stated, design values are the qualities and characteristics a game’s designer wants to embody in the game and its play experience. Design values help designers identify what kind of play experience they want to create and articulate some of the parts that will help their game generate that experience.

Designing games can be challenging in large part because of the way games work. Game designers have many reasons for creating games. Sometimes they want to share a certain kind of play. Sometimes they have ideas that are best expressed through a game. Regardless of the reasons, being able to fully realize the goals you have for a game can be difficult. This is because of the second-order design problem we discussed in Chapter 1, “Games, Design and Play;” the designer doesn’t have direct control of how players will play; instead, they simply define the parameters within which players play.

One of the best tools to guide the creation of play experiences is design values, a concept we borrow from the scholar Ivar Holm1 and the game designers Eric Zimmerman and Mary Flanagan. The term value here isn’t referring to the financial worth of the game. Instead, design values are the qualities and characteristics you want to embody in a game. This can reflect your own goals as a creator, but also the experience you want your audience to have.

1 Holm, Ivar. Ideas and Beliefs in Architecture and Industrial Design: How Attitudes, Orientations, and Underlying Assumptions Shape the Built Environment. Oslo School of Architecture and Design, 2006.

The broadest conception of design values is found in Ivar Holm’s work with architecture and industrial design. Holm identifies five key approaches: aesthetic, social, environmental, traditional, and gender based.

![]() Aesthetic: Aesthetic design values focus on the form and experience.

Aesthetic: Aesthetic design values focus on the form and experience.

![]() Social: Social design values focus on social change and the betterment of society.

Social: Social design values focus on social change and the betterment of society.

![]() Environmental: Environmental design values address the concerns of the environment and sustainability. This has more obvious application to architecture and product design, but is also of importance to games.

Environmental: Environmental design values address the concerns of the environment and sustainability. This has more obvious application to architecture and product design, but is also of importance to games.

![]() Traditional: Traditional design values use history and region as inspiration. In the context of architecture, this might apply to restoring a building to its original state or building in the local, traditional style. For game design, this might involve working within a genre, or reviving a historically important game.

Traditional: Traditional design values use history and region as inspiration. In the context of architecture, this might apply to restoring a building to its original state or building in the local, traditional style. For game design, this might involve working within a genre, or reviving a historically important game.

![]() Gender based: Gender-based design values bring feminist conceptions of gender equality into the design process.

Gender based: Gender-based design values bring feminist conceptions of gender equality into the design process.

The first game-specific conception of design values comes from Eric Zimmerman’s “play values,” which he describes as “the abstract principles that the game design would embody.”2 At times, this sort of design value relates directly to the “mechanical” nature of the game and its play—the actions players perform, the objects used, the goal of the game, and so on. Sometimes design values are adjectives like fast and long and twitchy—descriptions of what the game will feel like while playing. Other times design values refer to the “look and feel” of the game. Sometimes design values are more about the kind of player the designer envisions playing their game in the first place. Other times, design values are reminders of context—the location the game is to be played, the technological parameters of the platform, and so on. These fit within Holm’s aesthetic and traditional design values.

2 Although Zimmerman uses the term “play values,” our conception of design values is very much based on this idea. “Play as Research: The Iterative Design Process” www.ericzimmerman.com/texts/Iterative_Design.html.

In addition to the kind of play experience the designer wants to create, design values can be derived from different personal, political, or cultural values as well—in other words, social design values. Social design values might reflect a desire to express an idea about the human condition, an experience the designer once had and how it felt, or a political position based on personal or collective values. A good example of this notion of design values as an embodiment of political, feminist, and personal values comes from Mary Flanagan and Helen Nissenbaum’s project and book Values at Play.3 Flanagan and Nissenbaum developed a framework and toolkit for identifying political, social, and ethical values in games and exploring how designers might express their own perspectives. These connect to Holm’s social and gender design values but can as well extend to the environmental if we frame it more broadly.

3 Mary Flanagan and Helen Nissenbaum, Values at Play in Digital Games, 2014.

Generating Design Values

Creating design values is a process of determining what is important about the game—the play experience it provides, who it is for, the meaning it produces for its players, the constraints within which it must be created, and so on. We’ve found the best way to get started is with a series of questions that explore the who, what, why, where, and when of a game. While not every game begins with all of these, the following are the general questions to discuss while establishing the design values for a game.

![]() Experience: What does the player do when playing? As game designer and educator Tracy Fullerton puts it, what does the player get to do? And how does this make the player feel physically and emotionally?

Experience: What does the player do when playing? As game designer and educator Tracy Fullerton puts it, what does the player get to do? And how does this make the player feel physically and emotionally?

![]() Theme: What is the game about? How does it present this to players? What concepts, perspectives, or experiences might the player encounter during play? How are these delivered? Through story? Systems modeling? Metaphor?

Theme: What is the game about? How does it present this to players? What concepts, perspectives, or experiences might the player encounter during play? How are these delivered? Through story? Systems modeling? Metaphor?

![]() Point of view: What does the player see, hear, or feel? From what cultural reference point? How are the game and the information within it represented? Simple graphics? Stylized geometric shapes? Highly detailed models?

Point of view: What does the player see, hear, or feel? From what cultural reference point? How are the game and the information within it represented? Simple graphics? Stylized geometric shapes? Highly detailed models?

![]() Challenge: What kind of challenges does the game present? Mental challenge? Physical challenge? Or is it more a question of a challenging perspective, subject or theme?

Challenge: What kind of challenges does the game present? Mental challenge? Physical challenge? Or is it more a question of a challenging perspective, subject or theme?

![]() Decision-making: How and where do players make decisions? How are decisions presented?

Decision-making: How and where do players make decisions? How are decisions presented?

![]() Skill, strategy, chance, and uncertainty: What skills does the game ask of the player? Is the development of strategy important to a fulfilling play experience? Does chance factor into the game? From what sources does uncertainty develop?

Skill, strategy, chance, and uncertainty: What skills does the game ask of the player? Is the development of strategy important to a fulfilling play experience? Does chance factor into the game? From what sources does uncertainty develop?

![]() Context: Who is the player? Where are they encountering the game? How did they find out about it? When are they playing it? Why are they playing it?

Context: Who is the player? Where are they encountering the game? How did they find out about it? When are they playing it? Why are they playing it?

![]() Emotions: What emotions might the game create in players?

Emotions: What emotions might the game create in players?

This may seem like a lot to think about before designing a game. And it is a lot. But all these are important factors to consider at the beginning of the design process for a number of reasons. For one, design values establish the overarching concept, goals, and “flavor” of a game.

Just as important is the way design values create a shared understanding of the game. Most games are made collaboratively, and everyone on the team is likely to have opinions and ideas about what the game is and what its play experience should be. Design values allow the team members to agree on what they are making and why they are doing it. They also are an important check-in when great ideas come up but might not fit the game’s design values. Continuing to ask, “does this fit our design values?” will help resolve team conflicts, and, even if it’s a great idea, know whether it should be included in this game or a future project.

Example: Pong Design Values

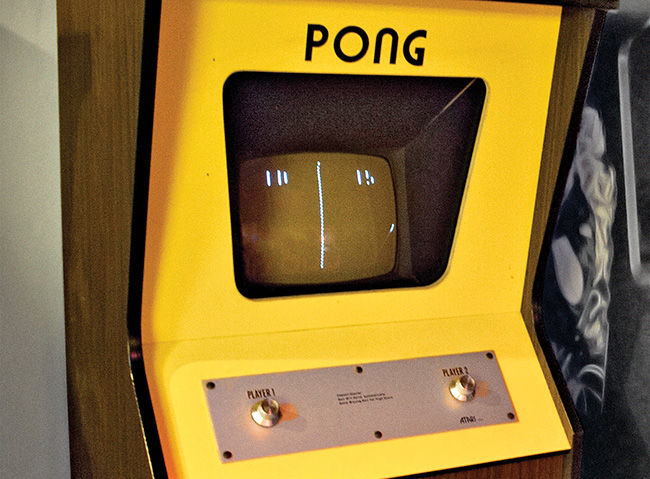

Having examples to draw from can be really helpful, particularly when exploring a new idea or concept—that’s why Part I, “Concepts,” is filled with examples drawn from games. Now that we’re moving from basic concepts into the design process, we’re going to use a speculative design example to illustrate things—Pong (see Figure 6.1). We’re going to pretend like we’re designing the classic arcade game. To start, the design values are the following:

![]() Experience: Pong is a two-player game based on a mashup between the physical games of tennis and ping pong. It uses a simple scoring system, allowing players to focus on competing for the best score.

Experience: Pong is a two-player game based on a mashup between the physical games of tennis and ping pong. It uses a simple scoring system, allowing players to focus on competing for the best score.

![]() Theme: Sportsball! Head to head competition!

Theme: Sportsball! Head to head competition!

![]() Point of view: Pong is presented from a top-down perspective, which takes the challenge of modeling gravity and hitting the ball over the net away from gameplay—focusing on the act of hitting the ball back and forth and trying to get it past your opponent’s paddle. The graphics are simple and abstract, also keeping the focus on fast and responsive gameplay.

Point of view: Pong is presented from a top-down perspective, which takes the challenge of modeling gravity and hitting the ball over the net away from gameplay—focusing on the act of hitting the ball back and forth and trying to get it past your opponent’s paddle. The graphics are simple and abstract, also keeping the focus on fast and responsive gameplay.

![]() Challenge: The game’s challenge is one of speed, eye-hand coordination, and hitting the ball in ways that your opponent is not expecting.

Challenge: The game’s challenge is one of speed, eye-hand coordination, and hitting the ball in ways that your opponent is not expecting.

![]() Decision-making: Decisions are made in real time, with a clear view of the ball’s trajectory and your opponent’s paddle.

Decision-making: Decisions are made in real time, with a clear view of the ball’s trajectory and your opponent’s paddle.

![]() Skill, strategy, chance, and uncertainty: Pong is a game of skill, with some chance related to the angle of the ball when it is served and some uncertainty of how your opponent will hit the ball and thus in how you will counter.

Skill, strategy, chance, and uncertainty: Pong is a game of skill, with some chance related to the angle of the ball when it is served and some uncertainty of how your opponent will hit the ball and thus in how you will counter.

![]() Context: The game is played in an arcade context, with your opponent next to you, enabling interaction on the game screen and in the real world.

Context: The game is played in an arcade context, with your opponent next to you, enabling interaction on the game screen and in the real world.

![]() Emotions: Pong is meant to generate the feeling of being completely focused, grace, intense competition, and excitement.

Emotions: Pong is meant to generate the feeling of being completely focused, grace, intense competition, and excitement.

Figure 6.1 Pong. Photo by Rob Boudon, used under Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic license.

Case Studies

To help see how design values play out in real-world examples, following are three real-world case studies: thatgamecompany’s Journey, Captain Game’s Desert Golfing, and Naomi Clark’s Consentacle.4

4 John writes about additional examples (including the writing of this book) in his essay “Design Values.” www.heyimjohn.com/design-values.

Case Study 1: thatgamecompany’s Journey

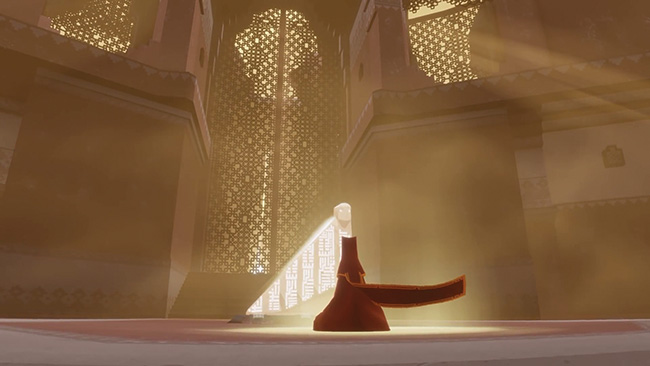

thatgamecompany’s Journey (see Figure 6.2) was an idea Jenova Chen, the company’s cofounder and creative director, had during his time as a student in the University of California’s Interactive Media and Games Division MFA program. He had been playing a lot of Massively Multiplayer Online games (MMOs) but was increasingly dissatisfied with the inability to really connect with other players on a human, emotional level. At the time, well before thatgamecompany formed, the game concept was beyond his abilities to pull off on his own. Years later, after thatgamecompany had Flow and Flower under its belt, Jenova thought it might be time to take on the challenges of Journey.

Figure 6.2 Journey.

In his talk at the 2013 Game Developer’s Conference about designing Journey, Jenova described the goal of designing a game that makes the player feel “lonely, small, and with a great sense of awe.”5 This was a design value: make a game that generates this kind of feeling in the player.

Jenova also wanted the game to involve multiplayer collaboration (in the case of Journey, two players). This led to a second design value for the game—being able to share the emotional response with another player and to have that act of sharing heighten the overall emotional impact.

In addition to these initial interests, the game’s design is informed by where it is played. Journey’s design values were influenced by the fact that it was being made for the PlayStation 3. Sony asked thatgamecompany to make a single-player game, which influenced how the cooperative mechanic was implemented. It’s seamless, and the experience doesn’t actually rely on other players being online and playing with you. Players appear and disappear as a natural occurrence in the world. And, of course, a game created to be experienced in your living room is going to be more cinematic and immersive than a game you might play on your phone while waiting for the bus, so the PlayStation platform informed the visual style and gameplay.

Another design value for Journey relates to the emotional and narrative arc of the play experience. Jenova was inspired by Joseph Campbell’s work on the Hero’s Journey, which builds upon the three-act structure common to theater and film. Jenova and his team began by creating a landscape that literally and emotionally tracked the arc of a traditional three-act narrative. This was intended to create an emotional flow from the highs of players sensing freedom, awe, and connections to the lows of being trapped, scared, and alone, and finally, closure through resolution.

During the design process, the design team went to visit sand dunes for inspiration for the game’s environment. While there, they noticed how enjoyable it was to move through the sand, climbing a tall dune and experiencing the anticipation of seeing what was at the top. This led to the idea of sliding in the sand, moving up and down the dunes with grace. This action fed well into the initial design value of creating a sense of awe as you move through the environments, and creating experiences that felt realistic—yet better than reality. Because on a real sand dune, unless you have a sled, it’s not really possible to slide down them—but in Journey, you surf the sand as if it were a wave (see Figure 6.3).

Figure 6.3 The player character sliding in the sand of Journey.

To achieve all these goals, Jenova and the thatgamecompany team had to work through a number of problems around player expectations and the conventions of multiplayer gameplay. In early prototypes, the game included puzzles involving pushing boulders together, or players pulling one another over obstacles.6 The goal was to create a multiplayer environment that encouraged collaboration. However, while playtesting, the team observed players pushing one another and fighting over resources. They soon realized that the kinds of actions allowed in the game and the feedback players were getting were all working against the collaborative spirit they were hoping to encourage. So they devised a solution that led to players being able to complete the journey alone as well as together, have equal access to resources, and have little effect on the other player’s ability to enjoy the game. And when players tended to use the in-game chat to bully or otherwise act in unsociable ways, the team had to make some difficult decisions about how to support player communication without allowing players to treat one another badly. This meant removing “chat” and replacing it with a single, signature tone. All of these decisions were informed by the design values of meaningful connection and a sense of awe.

Having the design values for the game allowed the team to remain focused on its goals and understand what they were aiming for as they developed prototypes. It took a good number of cycles through the iterative process to get the game to meet its design values and the goals initially set by Jenova. This was in large part because he wanted to do things that differed from most other games—there wasn’t a set formula or a precedent to work from. And so he and the thatgamecompany team had to experiment and try things out to craft, refine, and clarify the Journey player experience, and as they went, revisit their design values to make sure they were staying true to the team’s goals. In the end, all of the hard work paid off. Journey went on to win many awards, including The Game Developer’s Choice award for best game of the year.

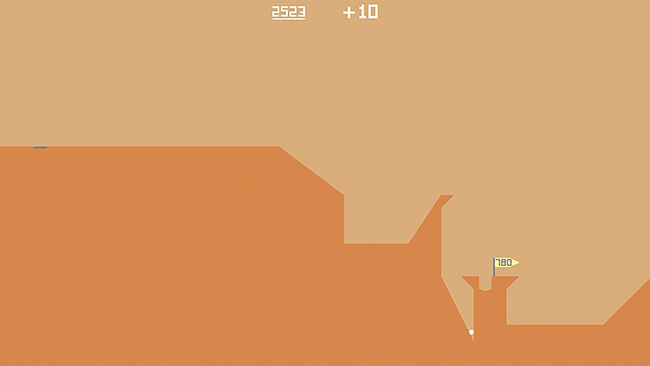

Case Study 2: Captain Game’s Desert Golfing

Desert Golfing (see Figure 6.4) is a deceptively simple game: using the tried-and-true Angry Birds-style “tap, pull, aim, and release” action, players hit a ball through a desert golf course of 3,000 (or more) holes. The game is deeply minimal in all ways: a single action for achieving a single goal (get the ball in the hole), yielding a single score (the total number of strokes) over an enormous number of holes, all with spare, flat color graphics and minimalist sound effects.

Figure 6.4 Captain Game’s Desert Golfing.

Desert Golfing began with a simple idea: make an “indie Angry Birds.” For Justin Smith, the game’s designer, this was shorthand for keeping all the pleasurable aspects of the “pinball stopper” action of Angry Birds, while removing a lot of the extraneous details that he felt detracted from the potential of this action. This was the first and primary design value for the game. It meant keeping the gameplay minimal, which kept a clear focus on the core action.

Justin describes his design approach as “asynchronous”—he collects ideas in a notebook (jotting down things like “indie Angry Birds”) and then when ready to work on a game, he flips through his notes to find ideas that connect. Justin always had an interest in sports games, and golf games in particular, which happened to lend itself well to the “pinball stopper” action. The interest in golf led to a thought experiment in which Justin imagined putting a golf game on top of thatgamecompany’s Journey. Though he didn’t do that, it did inspire the color palette and environment of the game. This provided the next design value: the characteristics of the game’s world.

Justin also thought about the minimum play experience and wanted players to be able to have a satisfying play session that was as small as a single stroke of the ball. This created the third design value: a deeply satisfying and discrete sense of pleasure from each action. This put a lot of importance on the “pinball stopper” action—the way it felt and how much nuance players could get from a simple gesture. Justin had to tinker with the responsiveness of the pull-and-release gesture, how feedback was visualized, and how the sound effects supported players’ understanding of what they did.

Knowing he wanted a golf game, Justin thought about how he might generate the holes. He was much more interested and attuned to procedurally generating the holes with code than manually designing them. This led to the idea of creating a seemingly endless golf course in a desert and a fourth design value: a sense of infiniteness to the game. To achieve this, Justin had to develop a set of more concrete rules to procedurally generate the first 3,000 holes of the game. This came through a series of trial-and-error experiments as he moved through iterative cycles of generating levels, evaluating the results, and making changes to the rules controlling the golf hole generation.

The final design value related to how players shared their Desert Golfing play experiences. He wanted to allow players to organically find things they wanted to share and discover about the game. This led to a couple of things. One was the gradual shifting color palette. It created a sense of discovery that players wanted to share with one another. Similarly was a player’s stroke total. Instead of creating leaderboards that would drive competition, Justin left it to players to find ways to share their scores. This led players to talk about this in person and through social media.

Desert Golfing is a great example of how design values can develop over time. Keeping a notebook for ideas and then returning to those ideas can begin the process of forming design values for a game, even from a simple notion, like an action or a setting inspired from another game. Justin Smith’s process of establishing design values was also influenced by the things he was interested in trying, such as the procedural generation of each level. Ultimately, design values are highly personal, based on choices about what you want the player experience to be and what you are interested in exploring as a designer.

Case Study 3: Naomi Clark’s Consentacle

Naomi Clark’s cardgame Consentacle (see Figure 6.5) is an example of a game created in response to the designer’s experiences with other media and playing other games. Consentacle grew out of a dissatisfaction with a particular strain of animé—Hentai, a genre notable for sexual acts that are often nonconsensual and violently portrayed, between tentacled monsters and young women. The traditions of the genre had the monsters in the position of power. Naomi wondered what might happen if she created a game in which both characters had equal power. The idea of a game where characters have equal power and engage in consensual activities formed the core design value for Consentacle, one that manifests in how the game is played, but also its politics.

Figure 6.5 Naomi Clark’s Consentacle.

There was one other thing from Hentai that Naomi drew inspiration from: the idea of developing alternative genders—the tentacled monster’s gender was ambiguous in Hentai animé. Naomi thought this worked as a perfect metaphor for queering gender, though at first she wasn’t exactly sure what form it would take. Together, these provided the theme of Consentacle, which is a strong guiding form of design value: finding ways to embed or express a theme through a game’s play.

With these ideas tucked away for a future project, Naomi began playing Android: Netrunner. Thanks to fellow game designer Mattie Brice, Naomi noticed that if you approached Android: Netrunner as a role-playing game, there was an intimacy to the interactions between the Corporation and the Runner. The Corporation was always vulnerable to the Runners, who in turn were continuously probing to gain information and points. It reminded Naomi of the dynamics of her game idea, Consentacle, so she decided to use this as a point of reference. This led to the second design value: exploring the inherent intimacy of collectible card game economic systems as a system for emotional engagement.

Naomi realized that a good deal of the intimacy came from the interactions around imperfect information spaces—the Corporation always had hidden information that the Runner had to think about and try to learn. Naomi began looking around for other cardgames and boardgames that used hidden information in similarly intimate ways. She began playing Antoine Bauza’s Hanabi (see Figure 6.6), a cardgame in which players can see one another’s cards, but not their own. In Hanabi, players must collaborate to help one another make the right decisions. This led Naomi to her next design value: collaborative gameplay as an exploration of consensual decision-making.

Figure 6.6 Antoine Bauza’s Hanabi.

With these components in place, Naomi quickly conceived of the basic play experience of Consentacle. Players—one a human, the other a tentacled alien—work together to build trust, which leads to satisfaction. This is done by simultaneously playing a card that, when combined, describes actions players can make around the collection of trust tokens and satisfaction tokens. In the beginner’s version of the game, the players can discuss which cards they will play, but in the advanced version, they are not allowed to talk and must develop alternate means of communicating with one another.

With constraint being a big part of a game designer’s toolkit, Naomi began to think about ways she could constrain the player’s ability to collaborate in a fun way. This led Naomi to think about the ways players could work together without regular communication. She came up with the idea of using what she calls “collaborative yomi”—players trying to guess one another’s actions in order to help one another, instead of the normal understanding of yomi as trying to best one another in a competition. This was the third design value for the game.

Because the game was seeking to encourage collaboration, Naomi decided fairly early on that she didn’t want the game to have an absolute win/lose condition. This was the fourth design value for the game. With this in mind, Naomi began thinking about ways to give players feedback on how they did without declaring a winner or loser (which would push against the collaborative nature of the game). Naomi took inspiration from the quizzes in Cosmopolitan magazine that rate along a scale. So the game used a scale to evaluate the collaborative score as well as the spread of points earned by the two players.

Consentacle’s unique gameplay is crafted around a set of design values reflecting real-world issues around consent. As she developed Consentacle, Naomi looked to games and other forms of media to provide insights into the design process, leading to interesting and ultimately unique solutions. Throughout the process, the design values in the game led Naomi’s research. This is important—it is easy to get lost looking at other games and media for influence—but if you have a strong set of design values, your search will have direction and purpose.

Summary

As you can see from our Pong thought experiment and the three case studies, design values are helpful in guiding the design process. They are guideposts in the journey through a game’s design. This is important because as you create your game and test it with others, you need a goal to work toward. Design values can also answer many of the questions that arise in the process of making a game. They function as tools for calibrating the team’s understanding of the game they hope to create, and they keep everyone working toward a unified play experience.

Here are the basic questions of design values:

![]() Experience: What does the player do when playing? As game designer and educator Tracy Fullerton puts it, what does the player get to do? And how does this make them feel physically and emotionally?

Experience: What does the player do when playing? As game designer and educator Tracy Fullerton puts it, what does the player get to do? And how does this make them feel physically and emotionally?

![]() Theme: What is the game about? How does it present this to players? What concepts, perspectives, or experiences might the player encounter during play? How are these delivered? Through story? Systems modeling? Metaphor?

Theme: What is the game about? How does it present this to players? What concepts, perspectives, or experiences might the player encounter during play? How are these delivered? Through story? Systems modeling? Metaphor?

![]() Point of view: What does the player see, hear, or feel? From what cultural reference point? How is the game and the information within it represented? Simple graphics? Stylized geometric shapes? Highly detailed models?

Point of view: What does the player see, hear, or feel? From what cultural reference point? How is the game and the information within it represented? Simple graphics? Stylized geometric shapes? Highly detailed models?

![]() Challenge: What kind of challenges does the game present? Mental challenge? Physical challenge? Challenges of perspective, subject, or theme?

Challenge: What kind of challenges does the game present? Mental challenge? Physical challenge? Challenges of perspective, subject, or theme?

![]() Decision-making: How and where do players make decisions? How are decisions presented? Is the information space perfect or imperfect?

Decision-making: How and where do players make decisions? How are decisions presented? Is the information space perfect or imperfect?

![]() Skill, strategy, chance, and uncertainty: What skills does the game ask of the player? Is the development of strategy important to a fulfilling play experience? Does chance factor into the game? From what sources does uncertainty develop?

Skill, strategy, chance, and uncertainty: What skills does the game ask of the player? Is the development of strategy important to a fulfilling play experience? Does chance factor into the game? From what sources does uncertainty develop?

![]() Context: Who is the player? Where are they encountering the game? How did they find out about it? When are they playing it? Why are they playing it?

Context: Who is the player? Where are they encountering the game? How did they find out about it? When are they playing it? Why are they playing it?

![]() Emotions: What emotions might the game create in players?

Emotions: What emotions might the game create in players?

Exercises

1. Take a game and “reverse engineer” its design values. Pay close attention to how the game makes you feel and how you imagine the designer might have captured those feelings in design values. Follow the list of design values from this chapter as a guide.

2. Take that same game and change three of the design values. Then modify it (on paper, or by changing the game’s rules) based on the new design values. How do these changes affect the whole? How different is the play experience?

All materials on the site are licensed Creative Commons Attribution-Sharealike 3.0 Unported CC BY-SA 3.0 & GNU Free Documentation License (GFDL)

If you are the copyright holder of any material contained on our site and intend to remove it, please contact our site administrator for approval.

© 2016-2026 All site design rights belong to S.Y.A.